The Global Importance of Machine Learning-Based Wearables and Digital Twins for Rehabilitation: A Review of Data Collection, Security, Edge Intelligence, Federated Learning, and Generative AI

Abstract

1. Introduction

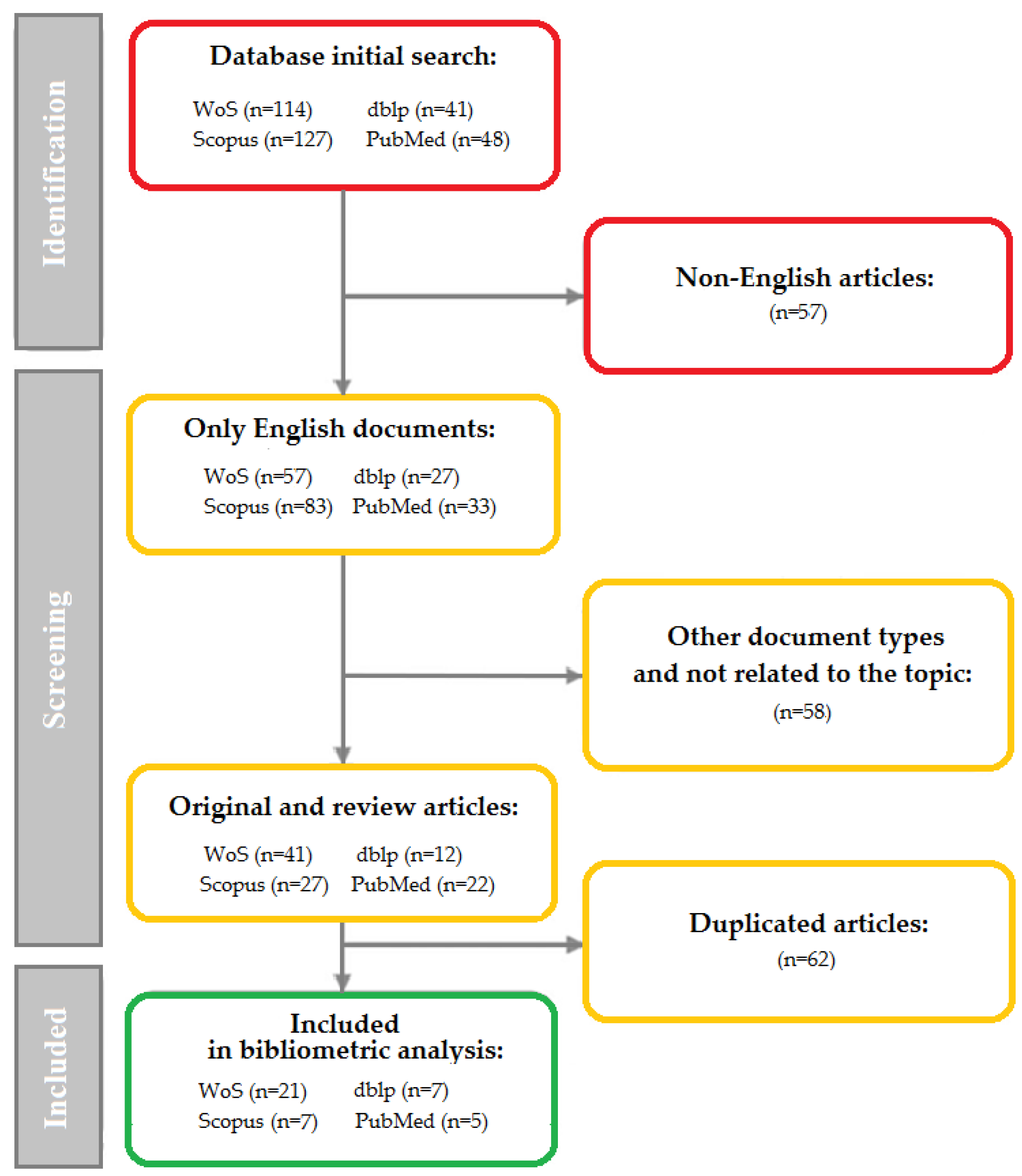

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

- RQ1: What is the most common source of publications concerning this topic (research institutions, countries, and, where possible, funding for research and publications)?

- RQ2: Who are the most influential authors and their teams?

- RQ3: What are the most popular topics and, where possible, how are these research topics evolving?

- RQ4: Which Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, formulated by the UN) are most frequently associated with the publications included in the review?

2.2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Data Sources

- in WoS: using the “Subject” field (consisting of title, abstract, keywords, and other keywords);

- in Scopus: using the article title, abstract, and keywords;

- in PubMed and dblp: using manual keyword sets.

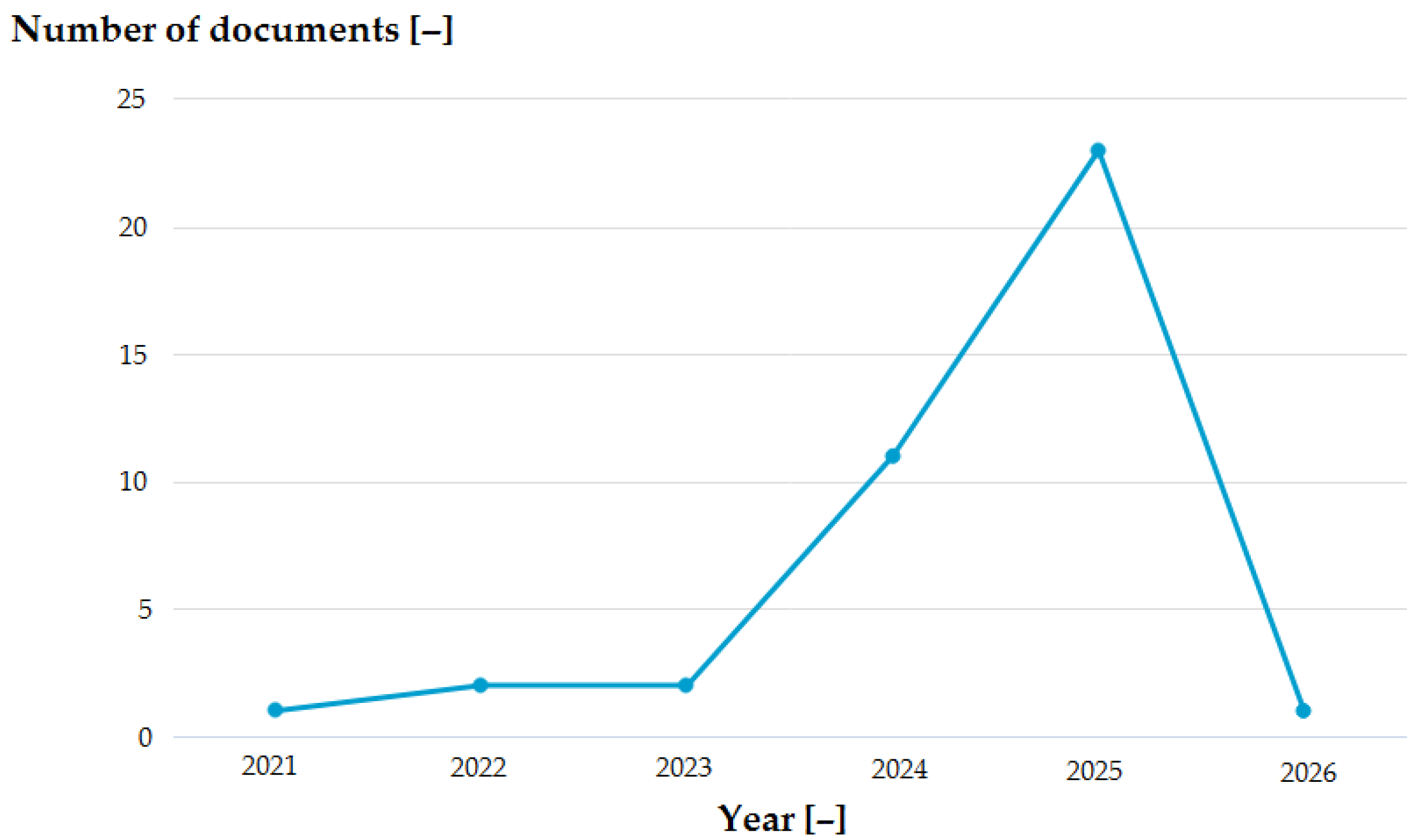

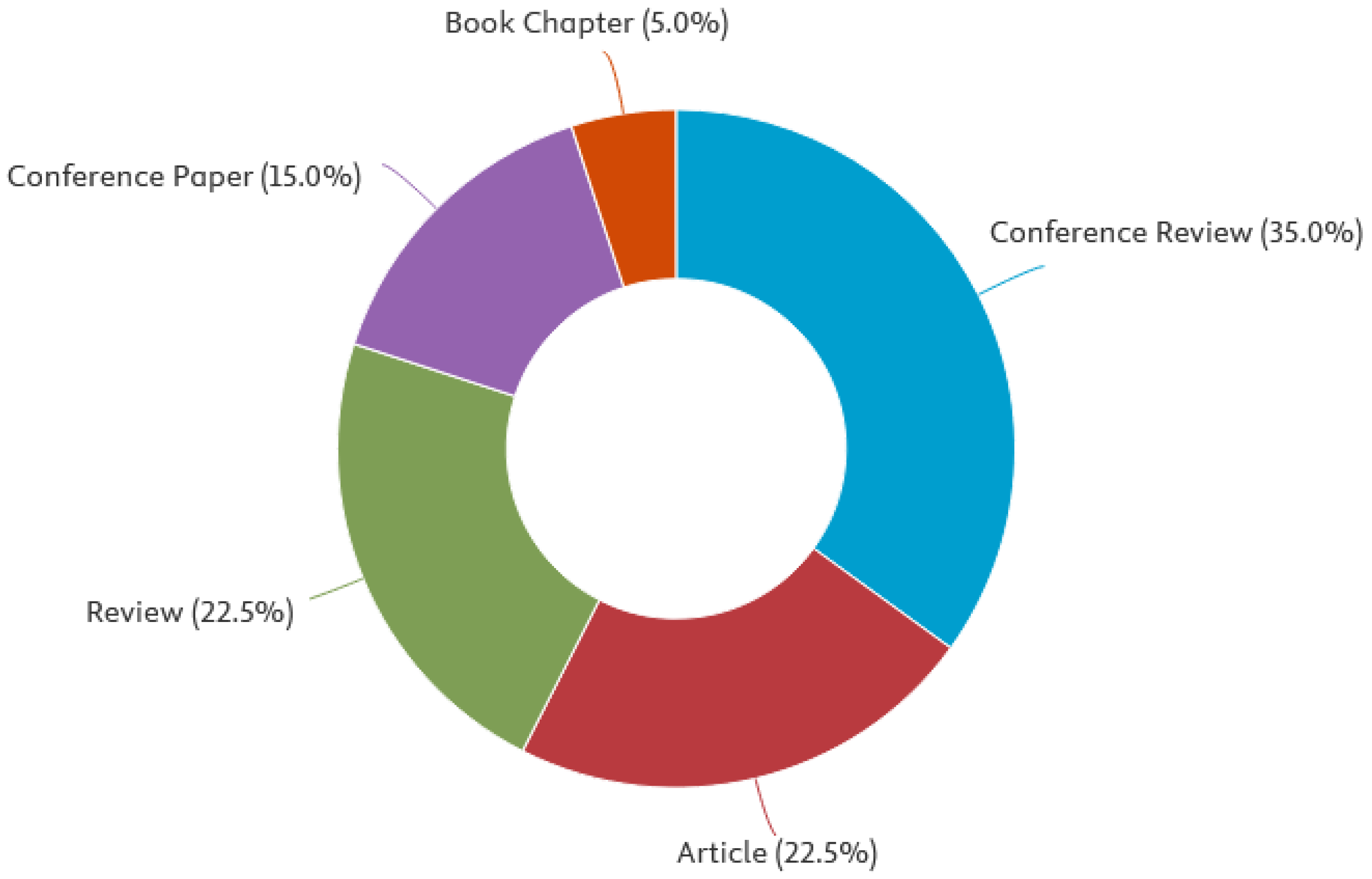

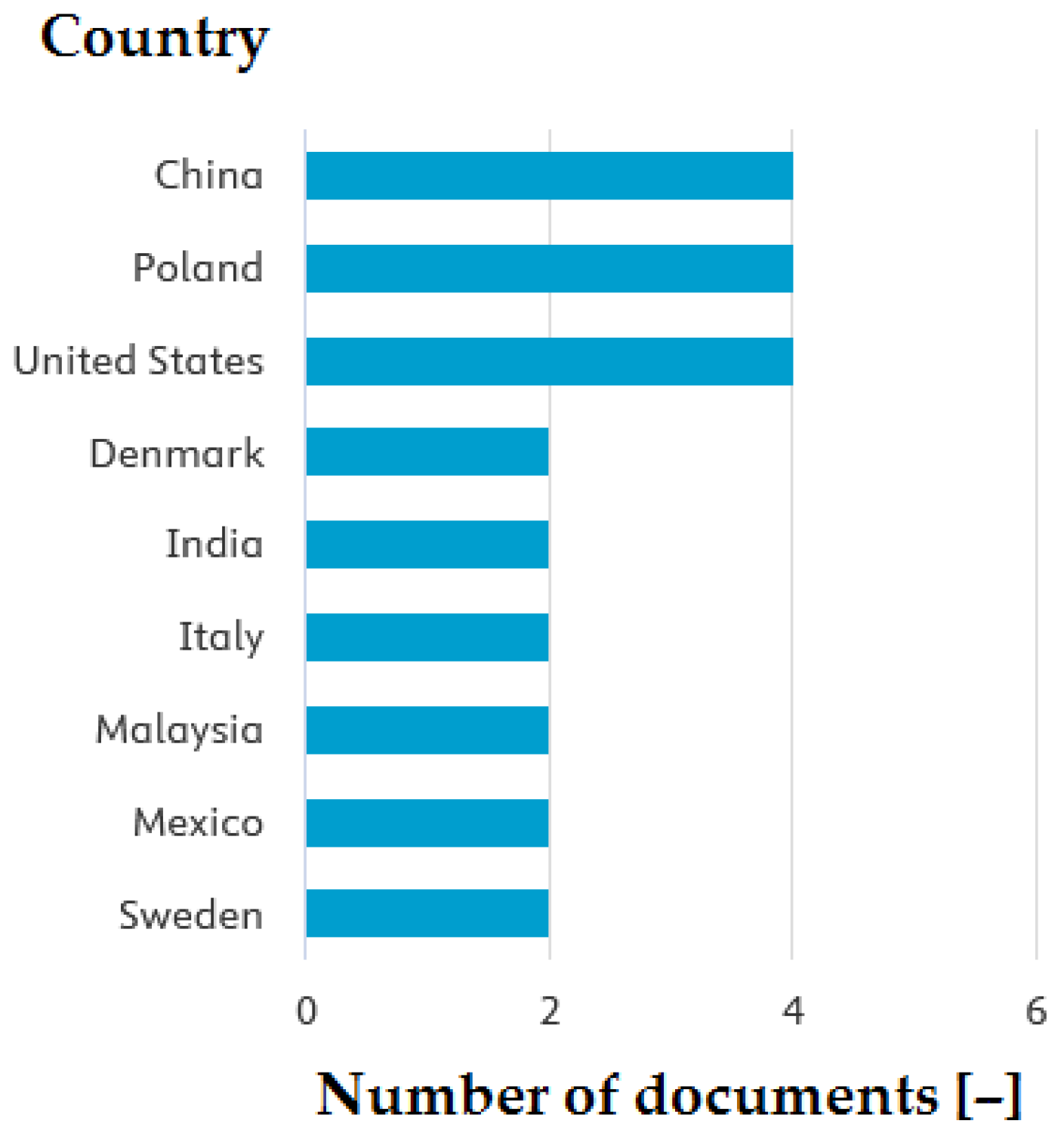

3.2. General Results of Analysis

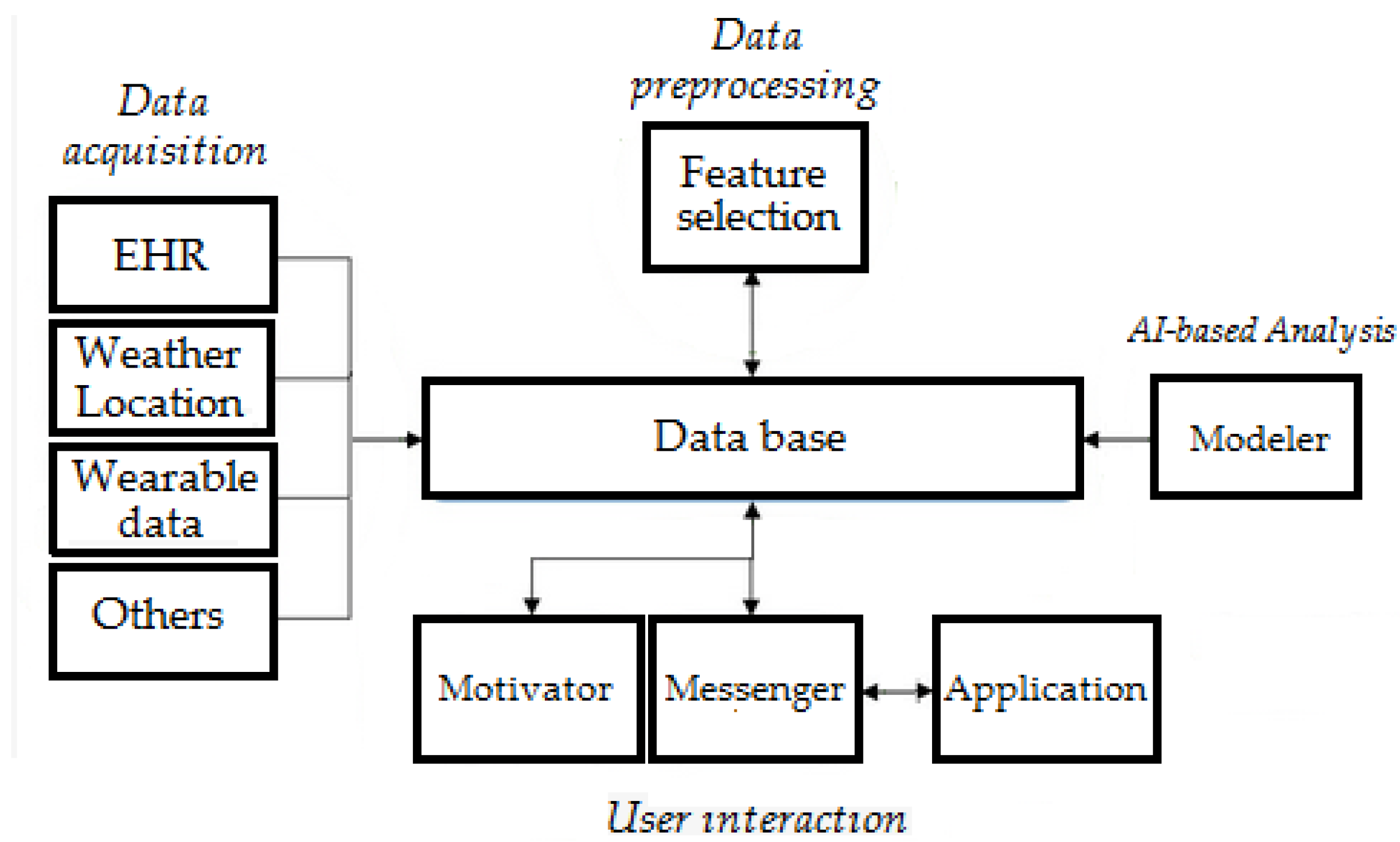

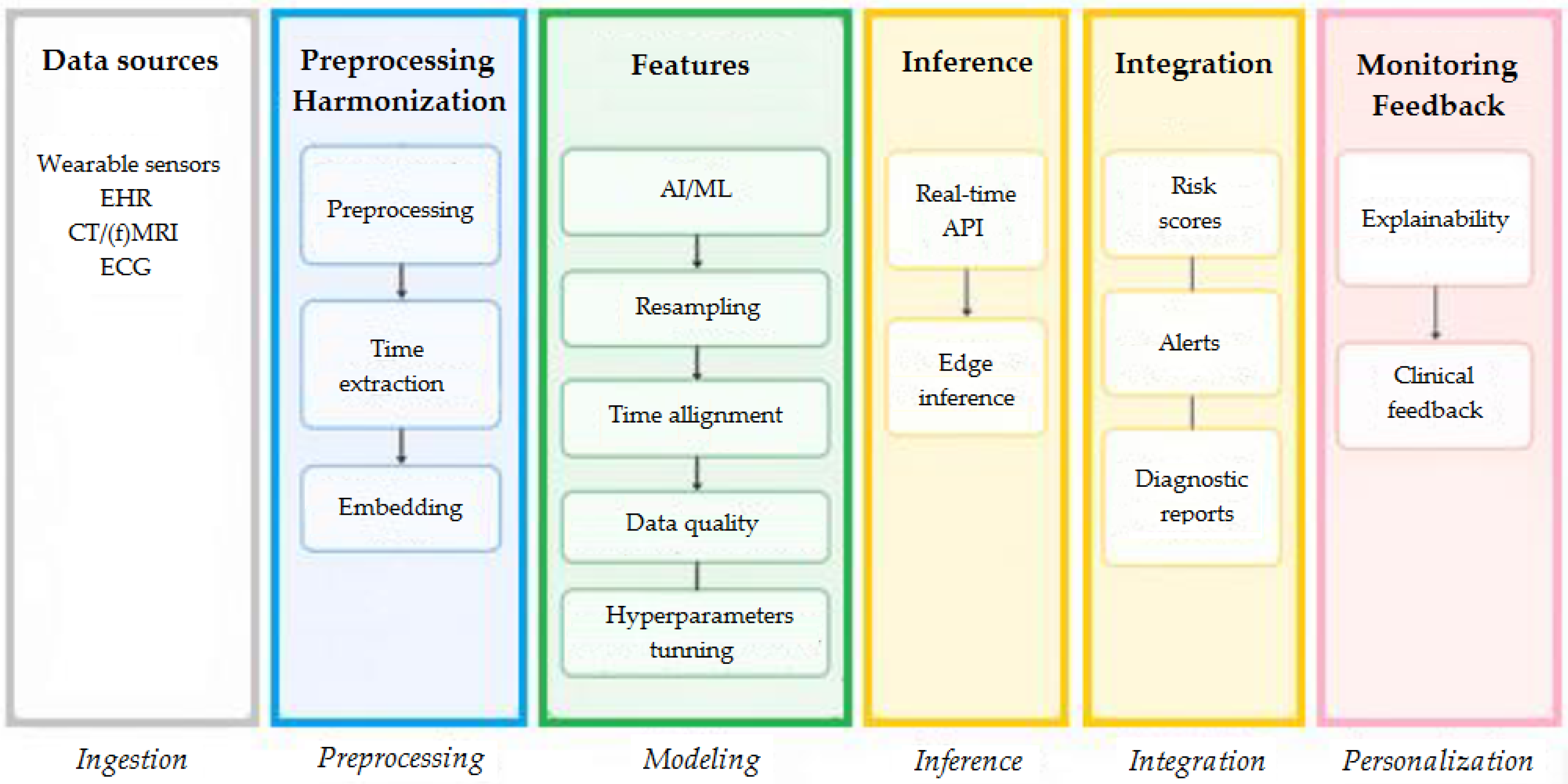

3.3. Data Collection

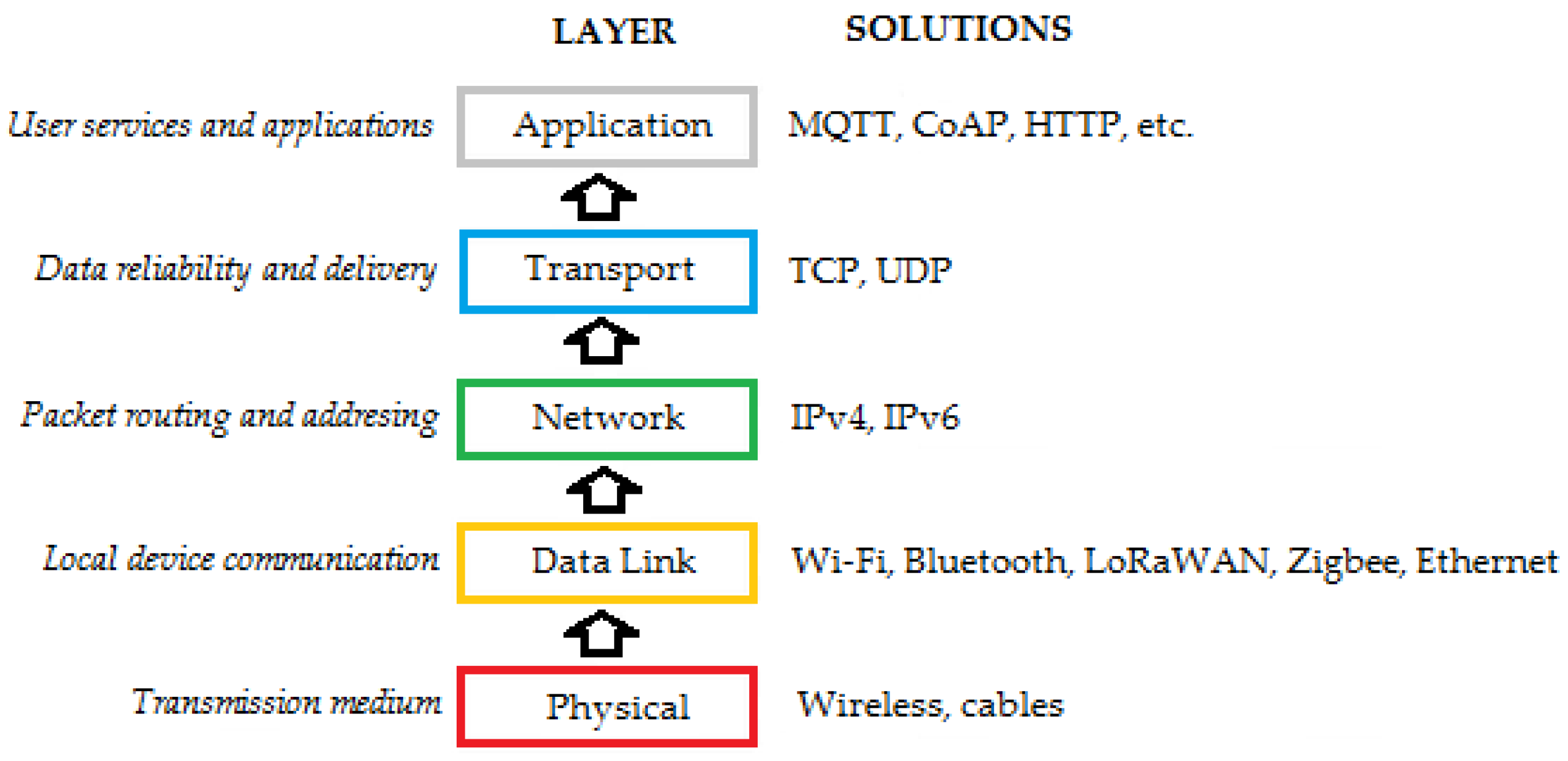

3.4. Security and Privacy

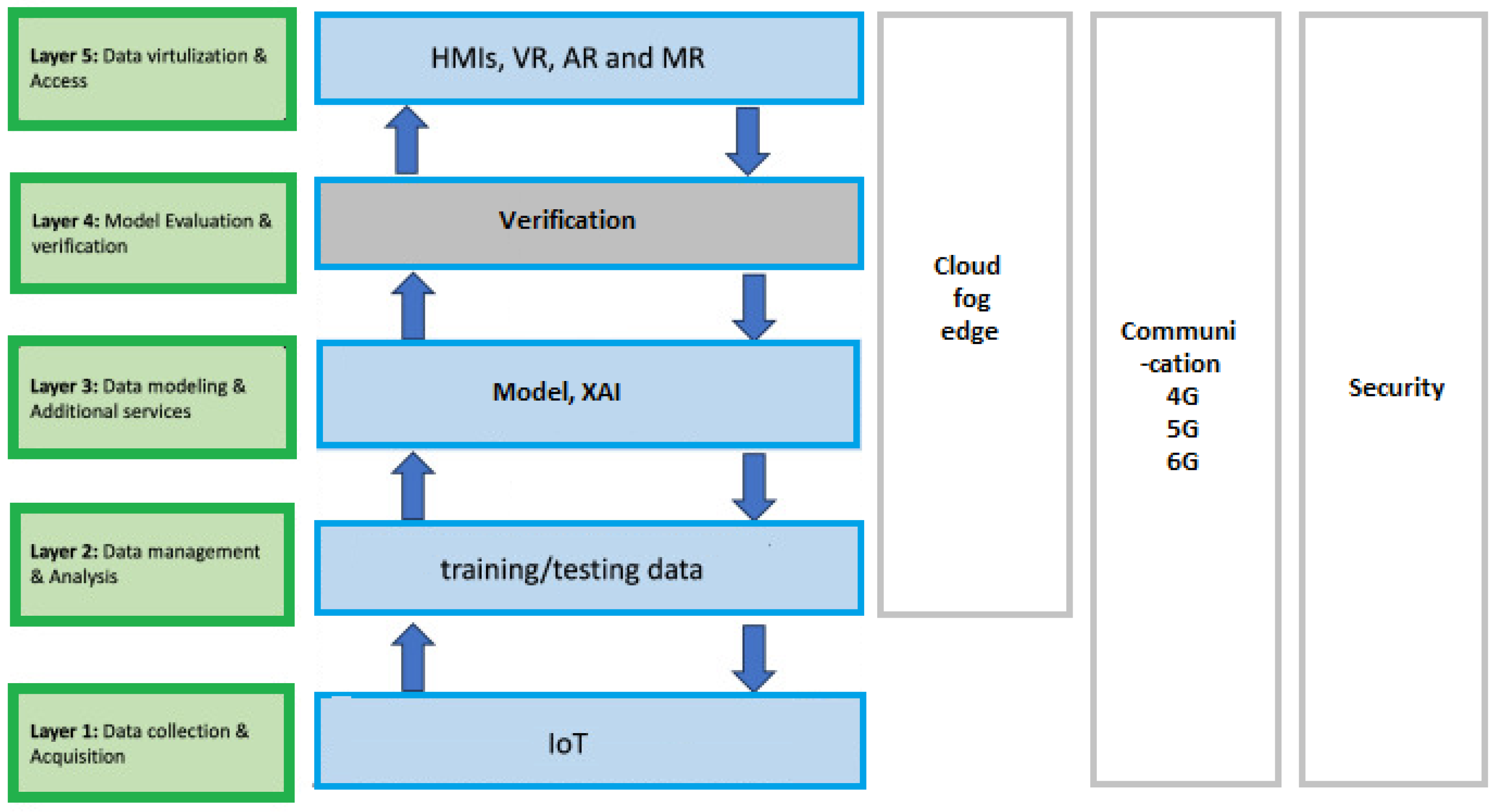

3.5. Edge Intelligence

3.6. Federated Learning

- differential privacy;

- homomorphic encryption.

3.7. Generative AI and Agentic AI

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

- severity (how much damage or impact the gap has if not addressed)—rated as high/medium/low with a short numerical metric;

- likelihood (how likely it is to occur given the current state of knowledge and practice)—rated as high/medium/low with a short numerical metric;

- practical mitigation actions or research directions as an element of the proposed road map.

| Research Gap Number and Name | Description | Severity | Likelihood | Mitigation/Ways to Solve (Research + Engineering) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||

| 1. Limited labeled clinical datasets and class imbalance | Small, biased datasets for many rehab conditions; minority classes (rare impairments) under-represented, reducing model generalization. | High | High | Consortium data sharing agreements; standardized minimal clinical data schemas; synthetic data augmentation (carefully validated); active learning to prioritize labeling; benchmark datasets with stratified sampling. |

| 2. Heterogeneous sensor modalities and metadata poverty | Different wearables, placements, sampling rates, missing provenance/metadata make model transfer and reproducibility hard. | High | High | Define and adopt metadata standards (device, sampling, placement, calibration); implement automated pre-processing pipelines; publish raw + preprocessed versions; use domain adaptation techniques. |

| 3. Longitudinal, contextual, ground-truth scarcity | Lack of long-term follow-up and labeled functional outcomes; outcomes often subjective. | High | Medium | Design longitudinal cohorts with standardized outcome measures (e.g., ICF/FAAM); use hybrid ground-truth (clinical assessments + ecological momentary assessment); incentivize multi-site registries. |

| 4. Real-world deployment / ecological validity gap | Models trained in lab/clinic fail in home environments (noise, activities, adherence). | High | High | Prioritize in-the-wild data collection, domain randomization, robust evaluation on home data, and continual learning pipelines to adapt on-device. |

| Security and privacy | ||||

| 5. Weak threat models for ML components | Insufficient formal analysis of adversarial, privacy, and misuse risks for wearable-to-digital twin pipelines. | High | High | Develop threat models covering sensor spoofing, model inversion, and data poisoning; adopt ML-specific security audits and red teaming. |

| 6. Privacy leakage from models and DTs | Models (or twin outputs) may leak sensitive clinical info (re-identification, membership inference). | High | High | Use differential privacy where feasible, DP-SGD for training, rigorous membership-inference testing, output minimization for twins, and privacy-preserving synthetic data evaluations. |

| 7. Secure edge-to-cloud communication and lifecycle | Lack of end-to-end secure update/authentication, device compromise risks, and insecure model update channels. | High | Medium | Use hardware root-of-trust (secure enclaves), mutual TLS, signed model updates, secure boot, and supply chain verification for devices and twins. |

| Edge computing/edge intelligence | ||||

| 8. Resource-constrained ML with clinical guarantees | Difficulty obtaining compact, low-latency models that preserve clinical-level accuracy and calibrated confidence. | High | High | Research on model compression plus uncertainty calibration (quantization-aware training + calibration layers); hybrid approaches where critical inference occurs on edge and heavy processing in secure cloud. |

| 9. Explainability and clinician trust at the edge | Black-box on-device models hinder adoption by clinicians and regulators. | Medium | High | Design explainable model families (attention, concept bottlenecks) with light-weight explanations (saliency + prototypical examples) suitable for edge. Evaluate human-in-the-loop acceptance studies. |

| 10. On-device continual and federated adaptation | Safe online updating on-device without catastrophic forgetting or privacy leak is immature. | High | Medium | Combine on-device incremental learning with replay buffers, elastic weight consolidation, and local validation checks; integrate rollback and audit trails. |

| FL | ||||

| 11. Statistical heterogeneity and fairness in FL | Clients (devices/patients) differ strongly—skewed data distributions cause biased global models and poor subgroup performance. | High | High | Personalized FL (per-client models, meta-learning), fairness-aware aggregation, subgroup evaluation, and client selection strategies; open benchmarks for rehab FL heterogeneity. |

| 12. Communication, stragglers, and participation incentives | Devices have intermittent connectivity, variable compute, and participation bias risks. | Medium | High | Asynchronous FL protocols, update compression/quantization, privacy-preserving incentive mechanisms (e.g., tokens), and simulation frameworks for straggler resilience. |

| 13. Privacy-utility tradeoff and verifiable compliance | Strong privacy mechanisms (DP, secure aggregation) often reduce utility; also, difficulty proving compliance to regulators. | High | Medium | Optimize privacy budget allocation per task, hybrid secure enclaves + DP, post hoc auditing tools for compliance, and standardized reporting templates for audits. |

| GenAI and DTs | ||||

| 14. Fidelity, realism, and clinical validity of synthetic patients/twins | Generative models (for augmentation or twin simulation) may produce unrealistic or clinically implausible behavior, risking model miscalibration. | High | Medium | Validate synthetic outputs vs. real longitudinal cohorts, include clinician-in-the-loop validation, use physics-informed generative models for biomechanical fidelity, and provide uncertainty bounds for generated data. |

| 15. Misuse risk: harmful or misleading clinical suggestions | Generative DTs or assistants may hallucinate clinical states or suggest inappropriate interventions. | High | Medium | Constrain generative outputs with rule-based clinical guards, retrieval-augmented generation anchored to verified sources, conservative confidence thresholds, and human oversight. |

| 16. Integration and interpretability of twin-derived policies | Translating twin simulations into safe, personalized therapy policies is underexplored (closed-loop control + human factors). | High | Low–Medium | Research safe policy extraction methods (safe RL with constraints), simulate-to-real transfer validation, pilot clinical trials with tight monitoring, and stop conditions. |

- Benchmarking: requires reporting performance, calibration, and resource utilization (memory, latency) for each subgroup in articles;

- Adversarial and privacy testing: includes membership inference, model inversion, and sensor spoofing tests as standard assessments;

- Human factors: measuring clinician acceptance, cognitive load, and trust in explainable interventions;

- Regulatory alignment: early engagement with clinical/regulatory stakeholders; creation of explainable technical documentation and audit trails for model updates.

- Development of standards and benchmarks: metadata schema, registration protocols, and open benchmark datasets (high leverage; addresses gaps 1–3, 11 from above Table).

- Implementation of strong privacy/security by design: threat modeling, signed updates, and secure aggregation (gaps 5–7, 13).

- Investments in long-term cohorts in the wild: multi-center registries with standardized outcomes (gaps 3–4, 14).

- FL and edge toolkits for rehabilitation: providing reference implementations (asynchronous FL, personalization, compression) and evaluation suites that simulate device connectivity and heterogeneity (gaps 8, 10–12).

- Clinical validation protocols for generative twins: clinician-in-the-loop checks, physical constraints, and conservative use cases (gaps 14–16).

4.2. Technological Implications

- cybersecurity;

- data management;

- ethical AI implementation;

- explainability (e.g., post hoc eXplainable AI-XAI).

4.3. Economic Implications

4.4. Societal Implications

4.5. Ethical and Legal Implications

4.6. Key Directions for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| DT | Digital twin |

| GAN | Generative adversarial network |

| GenAI | Generative AI |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| VAE | Variational autoencoder |

References

- Xu, D.; Zhou, H.; Jie, T.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Jemni, Y.; Quan, W.; Gao, Z.; Xiang, L.; Gusztav, F.; et al. Data-driven deep learning for predicting ligament fatigue failure risk mechanisms. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 301, 110519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietdijk, H.H.; Conde-Cespedes, P.; Dijkhuis, T.B.; Oldenhuis, H.K.E.; Trocan, M. A Survey on Machine Learning Approaches for Personalized Coaching with Human Digital Twins. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doungtap, S.; Petchhan, J.; Phanichraksaphong, V.; Wang, J.-H. Towards Digital Twins of 3D Reconstructed Apparel Models with an End-to-End Mobile Visualization. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damilos, S.; Saliakas, S.; Karasavvas, D.; Koumoulos, E.P. An Overview of Tools and Challenges for Safety Evaluation and Exposure Assessment in Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajewska, E.; Mikołajewski, D.; Mikołajczyk, T.; Paczkowski, T. Generative AI in AI-Based Digital Twins for Fault Diagnosis for Predictive Maintenance in Industry 4.0/5.0. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Dostatni, E.; Mikołajewski, D.; Pawłowski, L.; Węgrzyn-Wolska, K. Modern approach to sustainable production in the context of Industry 4.0. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2022, 70, e143828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A.; Fan, Z.; Day, C.; Barlow, C. Digital Twin: Enabling Technologies, Challenges and Open Research. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 108952–108971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhou, H.; Yang, G.; Li, X.; Yang, H. Human Digital Twin (HDT) Driven Human-Cyber-Physical Systems: Key Technologies and Applications. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 35, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, R.; Kwon, J.-W.; Kim, W.-T. A Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Concurrency Control of Federated Digital Twin for Software-Defined Manufacturing Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.-W.; Rubab, A.; Kim, W.-T. A Novel Energy Control Digital Twin System with a Resource-Aware Optimal Forecasting Model Selection Scheme. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serôdio, C.; Mestre, P.; Cabral, J.; Gomes, M.; Branco, F. Software and Architecture Orchestration for Process Controlin Industry 4.0 Enabled by Cyber-Physical Systems Technologies. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Salinas, J.S.; Kolla, H.; Sale, K.L.; Balakrishnan, U.; Poorey, K. GenAI-Based Digital Twins Aided Data Augmentation Increases Accuracy in Real-Time Cokurtosis-Based Anomaly Detection of Wearable Data. Sensors 2025, 25, 5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasmurzayev, N.; Amangeldy, B.; Imanbek, B.; Baigarayeva, Z.; Imankulov, T.; Dikhanbayeva, G.; Amangeldi, I.; Sharipova, S. Digital Cardiovascular Twins, AI Agents, and Sensor Data: A Narrative Review from System Architecture to Proactive Heart Health. Sensors 2025, 25, 5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztoń, E.; Rojek, I.; Mikołajewski, D. A Comparative Analysis of Anomaly Detection Methods in IoT Networks: An Experimental Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, N.; Molnar, A.; Georgakopoulos, D. Toward Improving Human Training by Combining Wearable Full-Body IoT Sensors and Machine Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.; Siau, K.L. Advances in IoT, AI, and Sensor-Based Technologies for Disease Treatment, Health Promotion, Successful Ageing, and Ageing Well. Sensors 2025, 25, 6207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihai, S.; Yaqoob, M.; Hung, D.V.; Davis, W.; Towakel, P.; Raza, M.; Karamanoglu, M.; Barn, B.; Shetve, D.; Prasad, R.V.; et al. Digital Twins: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Challenges, Trends and Future Prospects. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 2255–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukabayeva, T.; Zholshiyeva, L.; Karabayev, N.; Khan, S.; Alnazzawi, N. Cybersecurity Solutions for Industrial Internet of Things—Edge Computing Integration: Challenges, Threats, and Future Directions. Sensors 2025, 25, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Ren, L.; Wang, F.; Liu, R.; Pang, Z.; Deen, M.J. A Novel Cloud-Based Framework for the Elderly Health care Services Using Digital Twin. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 49088–49101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.O.; Arowoogun, J.O.; Okolo, C.A.; Chidi, R.; Babawarun, O. Ethical considerations in healthcare IT: Are view of data privacy and patient consentissues. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 1660–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Gan, Q.; Bahrami, S. A systematic survey of data mining and big data in human behavior analysis: Current datasets and models. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2022, 33, e4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barricelli, B.R.; Casiraghi, E.; Gliozzo, J.; Petrini, A.; Valtolina, S. Human Digital Twin for Fitness Management. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 26637–26664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, L.; Ali, A.; Nugent, C.; Ian, C.; Li, R.; Gao, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ning, H. Human Digital Twin: A Survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.05937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shengli, W. Is Human Digital Twin possible? Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Update 2021, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazab, M.; Khan, L.U.; Koppu, S.; Ramu, S.P.; M, I.; Boobalan, P.; Baker, T.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Aljuhani, A. Digital Twins for Healthcare 4.0—Recent Advances, Architecture, and Open Challenges. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2022, 12, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yi, C.; Okegbile, S.D.; Cai, J.; Shen, X. Networking Architecture and Key Supporting Technologies for Human Digital Twin in Personalized Healthcare: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 26, 706–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okegbile, S.D.; Cai, J.; Yi, C.; Niyato, D. Human Digital Twin for Personalized Healthcare: Vision, Architecture and Future Directions. IEEE Netw. 2022, 37, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Kotlarz, P.; Kozielski, M.; Jagodziński, M.; Królikowski, Z. Development of AI-Based Prediction of Heart Attack Risk as an Element of Preventive Medicine. Electronics 2024, 13, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rózanowski, K.; Sondej, T.; Lewandowski, J.; Łuszczyk, M.; Szczepaniak, Z. Multisensor System for Monitoring Human Psychophysiologic Statein Extreme Conditions with the Use of Microwave Sensor. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference Mixed Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems MIXDES 2012, Warsaw, Poland, 24–26 May 2012; pp. 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Jannasz, I.; Sondej, T.; Targowski, T.; Mańczak, M.; Obiała, K.; Dobrowolski, A.P.; Olszewski, R. Relationship between the Central and Regional Pulse Wave Velocity in the Assessment of Arterial Stiffness Depending on Gender in the Geriatric Population. Sensors 2023, 23, 5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, S.; Vu, G.; Gurupur, V.; King, C. Digital Convergence in Dental Informatics: A Structured Narrative Review of Artificial Intelligence, Internet of Things, Digital Twins, and Large Language Models with Security, Privacy, and Ethical Perspectives. Electronics 2025, 14, 3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tian, N.; Song, D.-A.; Zhang, L. Digital Twin-Enabled Multi-Service Task Offloading in Vehicular Edge Computing Using Soft Actor-Critic. Electronics 2025, 14, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabashkin, I. Federated Unlearning Framework for Digital Twin–Based Aviation Health Monitoring Under Sensor Drift and Data Corruption. Electronics 2025, 14, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Zhang, X.; Luosang, G.; Renzeng, D.; Renqing, D.; Ding, X. Federated Learning and Semantic Communication for the Metaverse: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Electronics 2025, 14, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifelo, Z.; Ding, J.; Ning, H.; Ain, Q.U.; Dhelim, S. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Metaverse for Sustainable Smart Cities: Technologies, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Electronics 2024, 13, 4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Du, Q.; Lu, L.; Zhang, S. Overview of the Integration of Communications, Sensing, Computing, and Storage as Enabling Technologies for the Metaverse over 6G Networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, E.; Iliuţă, M.E.; Moisescu, M.A. Digital Twin Types and Applications in Healthcare. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2024, 321, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibi, S.; Rajabifard, A.; Shojaei, D.; Wickramasinghe, N. Enhancing Healthcare through Sensor-Enabled Digital Twins in Smart Environments: A Comprehensive Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talal, M.; Zaidan, A.A.; Zaidan, B.B.; Albahri, A.S.; Alamoodi, A.H.; Albahri, O.S.; Alsalem, M.A.; Lim, C.K.; Tan, K.L.; Shir, W.L.; et al. Smart Home-based IoT for Real-time and Secure Remote Health Monitoring of Triage and Priority System using Body Sensors: Multi-driven Systematic Review. J. Med. Syst. 2019, 43, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozanovic, J.; Petrovic, M. From Concept to Practice: Unlocking the Potential of Digital Twins in Clinical Engineering. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2025, 324, 148–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondej, T.; Zawadzka, S. Influence of cuff pressures of automatics phygmomanometers on pulse oximetry measurements. Measurement 2022, 187, 110329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różanowski, K.; Piotrowski, Z.; Ciołek, M. Mobile Application for Driver’s Health Status Remote Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference IWCMC, Cagliari, Italy, 1–5 July 2013; Volume 2013, pp. 1738–1743. [Google Scholar]

- Kawala-Janik, A.; Bauer, W.; Al Bakri, A.; Cichoń, K.; Podraża, W. Implementation of low-pass fractional filtering for the purpose of analysis of electroencephalographic signals. Lect. Notes Electr. Eng. 2019, 496, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, P.; Grimm, B.; Garcia, F.; Fayad, J.; Ley, C.; Mouton, C.; Oeding, J.F.; Hirschmann, M.T.; Samuelsson, K.; Seil, R. Digital twin systems for musculoskeletal applications: A current concepts review. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2025, 33, 1892–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, D.G.; Saxby, D.J.; Pizzolato, C.; Worsey, M.; Diamond, L.E.; Palipana, D.; Bourne, M.; De Sousa, A.C.; Mannan, M.M.N.; Nasseri, A.; et al. Maintaining soldier musculoskeletal health using personalised digital humans, wearables and/or computer vision. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2023, 26 (Suppl. S1), S30–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, D. The future of in-field sports biomechanics: Wearables plus modelling compute real-time in vivo tissue loading to prevent and repair musculoskeletal injuries. Sports Biomech. 2024, 23, 1284–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shan, G.; Li, H.; Wang, L. A Wearable-Sensor System with AI Technology for Real-Time Biomechanical Feedback Training in Hammer Throw. Sensors 2022, 23, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, L.K.; Khan, F.; Shah, M.; Prasad, B.V.V.S.; Iwendi, C.; Biamba, C. Secure Smart Wearable Computing through Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems for Health Monitoring. Sensors 2022, 22, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin Khan, M.; Shah, N.; Shaikh, N.; Thabet, A.; Alrabayah, T.; Belkhair, S. Towards secure and trusted AI in health care: A systematic review of emerging innovations and ethical challenges. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2025, 195, 105780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.; Kim, H.K.; Carleton, A.; Munro, J.; Ferguson, D.; Monk, A.P.; Zhang, J.; Besier, T.; Fernandez, J. Integrating wearables and modelling for monitoring rehabilitation following total knee joint replacement. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 225, 107063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.B.; Quintero-Peña, C.; Moise, A.C.; Lumsden, A.B.; Corr, S.J. From Data to Decision: A Comprehensive Review of Real-Time Analytics and Smart Technologies in the Surgical Suite. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc. J. 2025, 21, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajewska, E. Associations between results of post-stroke NDT-Bobath rehabilitation in gait parameters, ADL and hand functions. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2013, 22, 731–738. [Google Scholar]

- Babarenda Gamage, T.P.; Elsayed, A.; Lin, C.; Wu, A.; Feng, Y.; Yu, J.; Gao, L.; Wijenayaka, S.; Nash, M.P.; Doyle, A.J.; et al. Vision for the 12 LABOURS Digital Twin Platform. In Proceedings of the 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society, Sydney, Australia, 24–27 July 2023; Volume 2023, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wu, Y.; Hu, M.; Chang, C.W.; Liu, R.; Qiu, R.; Yang, X. Current progress of digital twin construction using medical imaging. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2025, 26, e70226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewe, A.; Hunter, P.J.; Kohl, P. Computational modelling of biological systems now and then: Revisiting tools and visions from the beginning of the century. Philos. Trans. A 2025, 383, 20230384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Naeem, F.; Tariq, M.; Kaddoum, G. Federated Learning for Privacy Preservation in Smart Healthcare Systems: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.N.; Falcone, G.J.; Rajpurkar, P.; Topol, E.J. Multimodal biomedical AI. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1773–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarialiabad, H.; Pasdar, A.; Murrell, D.F.; Mostafavi, M.; Shakil, F.; Safaee, E.; Leachman, S.A.; Haghighi, A.; Tarbox, M.; Bunick, C.G.; et al. Enhancing randomized clinical trials with digital twins. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 2025, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojek, I.; Mroziński, A.; Kotlarz, P.; Macko, M.; Mikołajewski, D. AI-Based Computational Model in Sustainable Transformation of Energy Markets. Energies 2023, 16, 8059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amofa, S.; Xia, Q.; Xia, H.; Obiri, I.A.; Adjei-Arthur, B.; Yang, J.; Gao, J. Blockchain-secure patient Digital Twin in healthcare using smart contracts. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0286120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Hajjej, F.; Pasha, M.F.; Fang, O.H.; Khan, R.; Teo, J.; Zakarya, M. An Industrial IoT-Based Blockchain-Enabled Secure Searchable Encryption Approach for Healthcare Systems Using Neural Network. Sensors 2022, 22, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathalapalli, V.K.V.V.; Mohanty, S.P.; Kougianos, E.; Iyer, V.; Rout, B. PUFchain 3.0: Hardware-Assisted Distributed Ledger for Robust Authentication in Healthcare Cyber-Physical Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylock, R.H.; Zeng, X. A Blockchain Framework for Patient-Centered Health Records and Exchange (HealthChain): Evaluation and Proof-of-Concept Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Johnson, M.; Shervey, M.; Dudley, J.T.; Zimmerman, N. Privacy-Preserving Methods for Feature Engineering Using Blockchain: Review, Evaluation, and Proof of Concept. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Lohachab, A.; Dumontier, M.; Urovi, V. Privacy preservation in blockchain-based healthcare data sharing: A systematic review. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2025, 18, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahraoui, Y.; Hadjkouider, A.M.; Kerrache, C.A.; Calafate, C.T. Twin FedPot: Honeypot Intelligence Distillation into Digital Twin for Persistent Smart Traffic Security. Sensors 2025, 25, 4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sel, K.; Hawkins-Daarud, A.; Chaudhuri, A.; Osman, D.; Bahai, A.; Paydarfar, D.; Willcox, K.; Chung, C.; Jafari, R. Survey and perspective on verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification of digital twins for precision medicine. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedel, M.T.; Schurdak, M.E.; Stern, A.M.; Soto-Gutierrez, A.; Strobl, E.V.; Behari, J.; Taylor, D.L. Integrated Patient Digital and Biomimetic Twins for Precision Medicine: A Perspective. In Seminars in Liver Disease; Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Volume 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, N.; Hery, D.; Mahr, D.; Adler, S.O.; Stadlbauer, J.; Ahrens, T.D. Beyond the gender data gap: Co-creating equitable digital patient twins. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1584415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukhno, O.; Chukhno, N.; Araniti, G.; Campolo, C.; Iera, A.; Molinaro, A. Optimal Placement of Social Digital Twins in Edge IoT Networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, S.; Ayyash, M.; Almajali, S. Edge-Computing Architectures for Internet of Things Applications: A Survey. Sensors 2020, 20, 6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, F.; Abbasi, R.; Rehman, A.; Choi, G.S. An Advanced Algorithm for Higher Network Navigation in Social Internet of Things Using Small-World Networks. Sensors 2019, 19, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, D.; Ferrández, A.; Mora-Mora, H.; Peral, J. Internet of Things: A Review of Surveys Based on Context Aware Intelligent Services. Sensors 2016, 16, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Huang, Z.; Wang, L. Energy-Efficient Collaborative Task Computation Offloading in Cloud-Assisted Edge Computing for IoT Sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittón-Candanedo, I.; Alonso, R.S.; García, Ó.; Muñoz, L.; Rodríguez-González, S. Edge Computing, IoT and Social Computing in Smart Energy Scenarios. Sensors 2019, 19, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ji, P.; Ma, H.; Xing, L. A Comprehensive Review of Digital Twin from the Perspective of Total Process: Data, Models, Networks and Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 8306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.F.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.C.; Zhang, X.P. Systematic review of digital twin technology and applications. Vis. Comput. Ind. Biomed. Art 2023, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dihan, M.S.; Akash, A.I.; Tasneem, Z.; Das, P.; Das, S.K.; Islam, M.R.; Islam, M.M.; Badal, F.R.; Ali, M.F.; Ahamed, M.H.; et al. Digital twin: Data exploration, architecture, implementation and future. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukaniszyn, M.; Majka, Ł.; Grochowicz, B.; Mikołajewski, D.; Kawala-Sterniuk, A. Digital Twins Generated by Artificial Intelligence in Personalized Healthcare. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callista, M.; Tjahyadi, H. Digital Twin and Big Data in Healthcare. In Proceedings of the 2022 1st International Conference on Technology Innovation and Its Applications (ICTIIA), Tangerang, Indonesia, 23 September 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, M.; Chugh, R.; Gochhait, S.; Jibril, A.B. A Review on Digital Twin Technology in Healthcare. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Innovative Data Communication Technologies and Application (ICIDCA), Uttarakhand, India, 14–16 March 2023; pp. 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardašević, G.; Katzis, K.; Berbakov, L. Digital Twin Architecture for IoT-Based Healthcare Systems: A Preliminary Study. In Proceedings of the 2025 31st International Conference on Telecommunications (ICT), Budva, Montenegro, 28–29 April 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Esmaeilzadeh, P. Generative AI in Medical Practice: In-Depth Exploration of Privacy and Security Challenges. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e53008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Alam, T.; Househ, M.; Shah, Z. Federated Learning and Internet of Medical Things—Opportunities and Challenges. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 295, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Nguyen, T.N.; Ali, B.; Javed, M.A.; Mirza, J. On the Physical Layer Security of Federated Learning Based IoMT Networks. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, K.; Mozumder, M.A.I.; Joo, M.I.; Kim, H.C. BFLIDS: Blockchain-Driven Federated Learning for Intrusion Detection in IoMT Networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messinis, S.; Temenos, N.; Protonotarios, N.E.; Rallis, I.; Kalogeras, D.; Doulamis, N. Enhancing Internet of Medical Things security with artificial intelligence: A comprehensive review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 170, 108036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, W.; Nadkarni, G.N. Federated Learning in Healthcare Using Structured Medical Data. Adv. Kidney Dis. Health 2023, 30, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Asan, O.; Mansouri, M. Perspectives of Patients With Chronic Diseases on Future Acceptance of AI-Based Home Care Systems: Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, e49788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Hossain, M.S. Semi-supervised Federated Learning for Digital Twin 6G-enabled IIoT: A Bayesian estimated approach. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 66, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.; Lee, J.S. Federated influencer learning for secure and efficient collaborative learning in realistic medical database environment. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauneck, A.; Schmalhorst, L.; Kazemi Majdabadi, M.M.; Bakhtiari, M.; Völker, U.; Baumbach, J.; Baumbach, L.; Buchholtz, G. Federated Machine Learning, Privacy-Enhancing Technologies, and Data Protection Laws in Medical Research: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e41588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y. Medical Healthcare Digital Twin Reference Platform. In Proceedings of the 2024 Fifteenth International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN), Budapest, Hungary, 2–5 July 2024; pp. 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.; Osinga, S. Digital twins and dietary health technologies: Applying the capability approach. In Digital Transformation in Healthcare 5.0: Volume 1: IoT, AI and Digital Twin; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2024; pp. 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, B.; Kaushal, D.; Sharma, M.; Joshi, S.; Gopal, S.; Gupta, P. Integration of AI, Digital Twin and Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) For Healthcare 5.0: A Bibliometric Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Advances in Computation, Communication and Information Technology (ICAICCIT), Faridabad, India, 23–24 November 2023; pp. 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, A. DT-LSMAS: Digital Twin-Assisted Large-Scale Multiagent System for Healthcare Workflows. IEEE Syst. J. 2024, 18, 1883–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura Junior, V.; Kummer, B.R.; Moura, L.M.V.R. Population Health in Neurology and the Transformative Promise of Artificial Intelligence and Large Language Models. Semin. Neurol. 2025, 45, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Fan, C.; Xia, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y. Hybrid Electromagnetic-Triboelectric Hip Energy Harvester for Wearables and AI-Assisted Motion Monitoring. Small 2025, 21, e2500643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Patharkar, A.; Wu, T.; Lure, F.Y.M.; Chen, H.; Chen, V.C. STRIDE: Systematic Radar Intelligence Analysis for ADRD Risk Evaluation with Gait Signature Simulation and Deep Learning. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 10998–11006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonte, R.; Cioni, M. Critical spatiotemporal gait parameters for individuals with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hong Kong Physiother. J. 2021, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabin, M.S.R.; Yaroson, E.V.; Ilodibe, A.; Eldabi, T. Ethical and Quality of Care-Related Challenges of Digital Health Twins in Older Care Settings: Protocol for a Scoping Review. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2024, 13, e51153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCartney, H.; Main, A.; Weir, N.M.; Rai, H.K.; Ibrar, M.; Maguire, R. Professional-Facing Digital Health Technology for the Care of Patients With Chronic Pain: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e66457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosowicz, L.; Tran, K.; Khanh, T.T.; Dang, T.H.; Pham, V.A.; Ta Thi Kim, H.; Thi Bach Duong, H.; Nguyen, T.D.; Phuong, A.T.; Le, T.H.; et al. Lessons for Vietnam on the Use of Digital Technologies to Support Patient-Centered Care in Low-and Middle-Income Countries in the Asia-Pacific Region: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e43224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrušić, I.; Chiang, C.C.; Garcia-Azorin, D.; Ha, W.S.; Ornello, R.; Pellesi, L.; Rubio-Beltrán, E.; Ruscheweyh, R.; Waliszewska-Prosół, M.; Wells-Gatnik, W. Influence of next-generation artificial intelligence on headache research, diagnosis and treatment: The junior editorial board members’ vision—Part 2. J. Headache Pain. 2025, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozumder, M.A.I.; Sumon, R.I.; Uddin, S.M.I.; Athar, A.; Kim, H.C. The Metaverse for Intelligent Healthcare using XAI, Blockchain, and Immersive Technology. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Metaverse Computing, Networking and Applications (MetaCom), Kyoto, Japan, 26–28 June 2023; pp. 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Mahmud, T.; Roy, S.; Rahman, M.; Muhammad, M.; Islam, D.; Bin, A.A.; Chakma, R.; Hanip, A.H.; Mohammad, S. Digital Twin-Enabled Intelligent IoT Healthcare Systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Engineering (ECCE), Chittagong, Bangladesh, 13–15 February 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandan, M.; Naveen, P.; Nagarajan, G.; Janagiraman, S. Digital Twin Applications in Healthcare Facilities Management. In Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Blockchain Technology and Digital Twin for Smart Hospitals; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.A.; Chickarmane, V.; Ali Pour, F.S.; Shariari, N.; Roy, T.D. Validation of a Hospital Digital Twin with Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 11th International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI), Houston, TX, USA, 26–29 June 2023; pp. 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, B. Advancing Emergency Care With Digital Twins. JMIR Aging 2025, 8, e71777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlenberg, L.; Derungs, A.; Amft, O. Co-simulation of human digital twins and wearable inertial sensors to analyse gait event estimation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1104000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Gu, Y.; Deng, K.; Gao, Z.; Shim, V.; Wang, A.; Fernandez, J. Integrating personalized shape prediction, biomechanical modeling, and wearables for bone stress prediction in runners. NPJ Digit Med. 2025, 8, 1–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, N.H. Adversarial Examples on XAI-Enabled DT for Smart Healthcare Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajczyk, T.; Kłodowski, A.; Mikołajewska, E.; Fausti, D.; Petrogalli, D. Design and control of system for elbow rehabilitation: Preliminary findings. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 27, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varrassi, G.; Leoni, M.L.G.; Al-Alwany, A.A.; Sarzi Puttini, P.; Farì, G. Bioengineering Support in the Assessment and Rehabilitation of Low Back Pain. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frossard, L.; Langton, C.; Perevoshchikova, N.; Feih, S.; Powrie, R.; Barrett, R.; Lloyd, D. Next-generation devices to diagnose residuum health of individuals suffering from limb loss: A narrative review of trends, opportunities, and challenges. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2023, 26 (Suppl. S1), S22–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topini, A.; Sansom, W.; Secciani, N.; Bartalucci, L.; Ridolfi, A.; Allotta, B. Variable Admittance Control of a Hand Exoskeleton for Virtual Reality-Based Rehabilitation Tasks. Front. Neurorobot. 2022, 15, 789743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojek, I.; Mikołajewski, D.; Kotlarz, P.; Tyburek, K.; Kopowski, J.; Dostatni, E. Traditional Artificial Neural Networks Versus Deep Learning in Optimization of Material Aspects of 3D Printing. Materials 2021, 14, 7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarrias, A.; Rodriguez-Cianca, D.; Lanillos, P. Adaptive Torque Control of Exoskeletons Under Spasticity Conditions via Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/RAS-EMBS International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics (ICORR 2025), Chicago, IL, USA, 12–16 May 2025; Volume 2025, pp. 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadée, C.; Testa, S.; Barba, T.; Hartmann, K.; Schuessler, M.; Thieme, A.; Church, G.M.; Okoye, I.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; Hood, L.; et al. Medical digital twins: Enabling precision medicine and medical artificial intelligence. Lancet Digit. Health 2025, 7, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, D.; Hendriks, M.; Koopman, B.; Keijsers, N.; Sartori, M. A wearable gait lab powered by sensor-driven digital twins for quantitative biomechanical analysis post-stroke. Wearable Technol. 2024, 5, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Al-Jaroodi, J.; Jawhar, I.; Kesserwan, N. Leveraging Digital Twins for Healthcare Systems Engineering. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 69841–69853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narigina, M.; Romanovs, A.; Bruzgiene, R. Digital Twin Technology in Healthcare: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 11th Workshop on Advances in Information, Electronic and Electrical Engineering (AIEEE), Valmiera, Latvia, 31 May–1 June 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 27701:2025 Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Privacy Information Management Systems—Requirements and Guidance, Edition 2. 2025. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/27701 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- ISO/IEC 27001:2022 Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements, Edition 3. 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/27001 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- GDPR-Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- MDR-Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on Medical Devices, Amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and Repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/745/oj/eng (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Tyagi, A.K. Sensors and Digital Twin Application in Healthcare Facilities Management. In Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Blockchain Technology and Digital Twin for Smart Hospitals; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Zhu, S.; Dai, J. Feasibility Study of Intelligent Healthcare Based on Digital Twin and Data Mining. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Information Science and Artificial Intelligence (CISAI), Kunming, China, 17–19 September 2021; pp. 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée, A. Digital Twins for Personalized Medicine Require Epidemiological Data and Mathematical Modeling: Viewpoint. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e72411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrušić, I. Digital phenotyping for migraine: A game-changer for research and management. Cephalalgia 2025, 45, 3331024251363568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagna, S.; Stagni, R.; Pierucci, G.; Aceti, A.; Cordelli, D.M.; Bisi, M.C. Digital Twins for Monitoring Neuromotor Development in Preterm Infants: Conceptual Framework and Proof-of-concept Study. J. Med. Syst. 2025, 49, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, D.K.; Nashwan, A.J. Harnessing Artificial Intelligence in Lifestyle Medicine: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions. Cureus 2025, 17, e85580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, M.; Seoni, S.; Campagner, A.; Gertych, A.; Acharya, U.R.; Molinari, F.; Cabitza, F. Explainability and uncertainty: Two sides of the same coin for enhancing the interpretability of deep learning models in healthcare. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2025, 197, 105846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leivaditis, V.; Maniatopoulos, A.A.; Lausberg, H.; Mulita, F.; Papatriantafyllou, A.; Liolis, E.; Beltsios, E.; Adamou, A.; Kontodimopoulos, N.; Dahm, M. Artificial Intelligence in Thoracic Surgery: A Review Bridging Innovation and Clinical Practice for the Next Generation of Surgical Care. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhubl, S.R.; Sekaric, J.; Gendy, M.; Guo, H.; Ward, M.P.; Goergen, C.J.; Anderson, J.L.; Amin, S.; Wilson, D.; Paramithiotis, E.; et al. Development of a personalized digital biomarker of vaccine-associated reactogenicity using wearable sensors and digital twin technology. Commun. Med. 2025, 5, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, D.H.; Tien, C.L.; Yeh, Y.L.; Guo, Y.R.; Lin, C.S.; Chen, C.C.; Chang, C.M. Design of Digital-Twin Human-Machine Interface Sensor with Intelligent Finger Gesture Recognition. Sensors 2023, 23, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Zhou, Y.; Sitaraman, S.K.; Tentzeris, M.M. Additively manufactured flexible on-package phased array antennas for 5G/mm Wave wearable and conformal digital twin and massive MIMO applications. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roßkopf, S.; Meder, B. Healthcare 4.0—Medizin im Wandel [Healthcare 4.0-Medicine in transition]. Herz 2024, 49, 350–354. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkenhagen, A.; Babic, A. Developing Lifestyle-Focused Digital Twin Archetypes in Heart Care. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2025, 323, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, D.; Gonsard, A. Definitions and Characteristics of Patient Digital Twins Being Developed for Clinical Use: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e58504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Yu, C.; Tian, Z.; Liu, X.; Cao, J.; Liu, L.; Du, C.; Jiang, M. Intelligent Wearable System With Motion and Emotion Recognition Based on Digital Twin Technology. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 26314–26328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.; Nguyen, H.; Cao, H.L.; Bui, T.T.; Ngo, H.Q.T. A Digital Twin-Empowered Framework for Interactive Consumers in Manufacturing Using Wearable Device. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 146557–146568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, H.; Yue, P.; Duan, Q.; Mo, S.; Zhao, Z.; Qu, X.; Hu, X. Development of a low-cost and user-friendly system to create personalized human digital twin. In Proceedings of the 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Sydney, Australia, 24–27 July 2023; Volume 2023, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Z.; Saikia, M.J. Digital Twins for Health care Using Wearables. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzi, F.; Farahani, B.; Daneshmand, M.; Grise, K.; Song, J.; Saracco, R.; Wang, L.L.; Lo, K.; Angelov, P.; Soares, E.; et al. Harnessing the Power of Smart and Connected Health to Tackle COVID-19: IoT, AI, Robotics, and Blockchain for a BetterWorld. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 12826–12846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, S.S.W.; Ning, S.; Wong, N.Y.K.; Chan, J.; Ng, K.S.; Kwok, B.O.T.; Anders, R.L.; Lam, S.C. Leveraging machine learning in nursing: Innovations, challenges, and ethical insights. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1514133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suraci, C.; Pizzi, S.; Molinaro, A.; Araniti, G. Business-Oriented Security Analysis of 6G for eHealth: An Impact Assessment Approach. Sensors 2023, 23, 4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Payra, S.; Singh, S.K. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Pharmacological Research: Bridging the Gap Between Data and Drug Discovery. Cureus 2023, 15, e44359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danelakis, A.; Stubberud, A.; Tronvik, E.; Matharu, M. The Emerging Clinical Relevance of Artificial Intelligence, Data Science, and Wearable Devices in Headache: A Narrative Review. Life 2025, 15, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hu, C.; Luo, X. Research Status, Hotspots and Perspectives of Artificial Intelligence Applied to Pain Management: A Bibliometric and Visual Analysis. In Updates in Surgery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Vinces, C.; Martínez, M.C.; Atorrasagasti-Villar, A.; Rodríguez, M.D.M.G.; Ezpeleta, D.; Irimia, P. Artificial intelligence in headache medicine: Between automation and the doctor-patient relationship. A systematic review. J. Headache Pain 2025, 26, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkenhagen, A.; Babic, A. Establishing a Digital Twin Archetype Through Climate Concerns and Quality of Life Data. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2025, 328, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, S.; Cassidy, R.; Nanni, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, M.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, T.; Sinha, A.; Pandian, B.; et al. Medical data sharing and synthetic clinical data generation—Maximizing biomedical resource utilization and minimizing participant re-identification risks. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.C.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Yap, N.A.; Wang, R.; Cheng, W.; Xu, X.; Ju, L.A. Sensing the Future of Thrombosis Management: Integrating Vessel-on-a-Chip Models, Advanced Biosensors, and AI-Driven Digital Twins. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 1507–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Lee, C. Triboelectric Mat Multimodal Sensing System (TMMSS) Enhanced by Infrared Image Perception for Sleep and Emotion-Relevant Activity Monitoring. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2407888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birla, M.; Rajan Roy, P.G.; Gupta, I.; Malik, P.S. Integrating Artificial Intelligence-Driven Wearable Technology in Oncology Decision-Making: A Narrative Review. Oncology 2025, 103, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androulakis, I.P.; Cucurull-Sanchez, L.; Kondic, A.; Mehta, K.; Pichardo, C.; Pryor, M.; Renardy, M. The dawn of a new era: Can machine learning and large language models reshape QSP modeling? J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2025, 52, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillgallon, R.; Bergami, G.; Morgan, G. Federated Load Balancing in Smart Cities: A 6G, Cloud, and Agentic AI Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage Name | Tasks |

|---|---|

| Defining research goal(s) | Defining goals of the bibliometric analysis |

| Selecting databases and data collections | Selecting appropriate dataset(s) and developing research queries according to the study goals |

| Data preprocessing | Cleaning the collected dataset(s) to remove duplicates and irrelevant records |

| Bibliometric software selection | Choosing suitable bibliometric software/tools for analysis |

| Data analysis | Description, author, journal, area, topics, institution, country, etc. |

| Visualization (if possible) | Visualizing the analysis results to present insights |

| Interpretation and discussion | Interpreting findings in the context of the research goals and RQs |

| Parameter/Feature | Detailed Description |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | Books (and chaptersin books), articles (original, reviews, communication, editorials), and conference proceedings, in English |

| Exclusion criteria | Older than 10 years, letters, conference abstracts without full text, other languages than English |

| Exact keywords used | (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning”) AND “digital twin” AND (“rehabilitation” OR “physiotherapy” OR “physical therapy”) |

| Used field codes (WoS) | “Subject” field (consisting of title, abstract, keyword plus and other keywords): (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning”) AND “digital twin” AND (“rehabilitation” OR “physiotherapy” OR “physical therapy”) |

| Used field codes (Sopus) | Article title, abstract, and keywords: (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning”) AND “digital twin” AND (“rehabilitation” OR “physiotherapy” OR “physical therapy”) |

| Used field codes (PubMed) | Manually: (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning”) AND “digital twin” AND (“rehabilitation” OR “physiotherapy” OR “physical therapy”) |

| Used field codes (dblp) | Manually: (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning”) AND “digital twin” AND (“rehabilitation” OR “physiotherapy” OR “physical therapy”) |

| Boolean operators used | Yes, e.g., (“rehabilitation” OR “physiotherapy” OR “physical therapy”) |

| Applied filters | Results refined by publication year, document type (e.g., articles, reviews), and subject area (e.g., industry, engineering). |

| Iteration and validation options | Queries are run iteratively, refined based on results, and validated by ensuring that relevant publications appear among the top results |

| Leverage truncation and wildcards used | Used symbols like * for word variations and ? for alternative spellings |

| Parameter/Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Leading types of publication | Conference review (35.0%), article (22.5%), review (22.5%), conference paper (15.0%) |

| Leading areas of science | Computer science (34.6%), Mathematics (19.2%), Engineering (17.9%) |

| Leading countries | USA (10%), China (10%), Poland (10%) |

| Leading scientists | None observed |

| Leading affiliations | None observed |

| Leading funders (where information is available) | Natural Science Foundation of China (5%) |

| Sustainable development goals | Good health and well-being, Quality education, Gender equality, Zero hunger |

| Area | Key Technical Limitations |

|---|---|

| Data collection | Sensor noise and drift, inconsistent sampling rates, limited multimodal integration, missing or incomplete rehabilitation data, and difficulties capturing complex biomechanics |

| Security and privacy | Vulnerable data transmission channels, risks of re-identification even after anonymization, limited on-device encryption capacity, and secure key management challenges |

| Edge intelligence | Constrained compute, memory, and battery, real-time inference bottlenecks, model compression trade-offs, reducing accuracy, heterogeneous hardware across users |

| FL | Patient data harming convergence, high communication overhead, device dropout, secure aggregation complexity, vulnerability to poisoning or inference attacks |

| GenAI | Hallucinations, lack of biomechanical grounding, limited explainability; risk of generating clinically unsafe recommendations, and high computational requirements. |

| Area | Limitation Type | Key Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Adoption and deployment | Organizational/Economic | High cost of devices, integration with hospital IT, low digital literacy among clinicians or patients, and maintenance and calibration burdens. |

| Regulatory | Compliance/Governance | Unclear approval pathways for adaptive/continually learning models; cross-border data governance conflicts; lack of standards for wearable-derived biomarkers; auditability requirements. |

| Clinical Use | Safety/Efficacy | Limited clinical validation; variability in patient adherence; challenges in personalizing models for diverse conditions; risk of overreliance on algorithmic outputs |

| Ethical and Social | Trust/Fairness | Bias in training data leading to unequal outcomes; opaque decision-making; concerns over surveillance; uncertainty about clinician liability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piechowiak, M.; Goch, A.; Panas, E.; Masiak, J.; Mikołajewski, D.; Rojek, I.; Mikołajewska, E. The Global Importance of Machine Learning-Based Wearables and Digital Twins for Rehabilitation: A Review of Data Collection, Security, Edge Intelligence, Federated Learning, and Generative AI. Electronics 2025, 14, 4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234699

Piechowiak M, Goch A, Panas E, Masiak J, Mikołajewski D, Rojek I, Mikołajewska E. The Global Importance of Machine Learning-Based Wearables and Digital Twins for Rehabilitation: A Review of Data Collection, Security, Edge Intelligence, Federated Learning, and Generative AI. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234699

Chicago/Turabian StylePiechowiak, Maciej, Aleksander Goch, Ewelina Panas, Jolanta Masiak, Dariusz Mikołajewski, Izabela Rojek, and Emilia Mikołajewska. 2025. "The Global Importance of Machine Learning-Based Wearables and Digital Twins for Rehabilitation: A Review of Data Collection, Security, Edge Intelligence, Federated Learning, and Generative AI" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234699

APA StylePiechowiak, M., Goch, A., Panas, E., Masiak, J., Mikołajewski, D., Rojek, I., & Mikołajewska, E. (2025). The Global Importance of Machine Learning-Based Wearables and Digital Twins for Rehabilitation: A Review of Data Collection, Security, Edge Intelligence, Federated Learning, and Generative AI. Electronics, 14(23), 4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234699