Validating a Wearable VR Headset for Postural Sway: Comparison with Force Plate COP Across Standardized Sensorimotor Tests

Abstract

1. Introduction

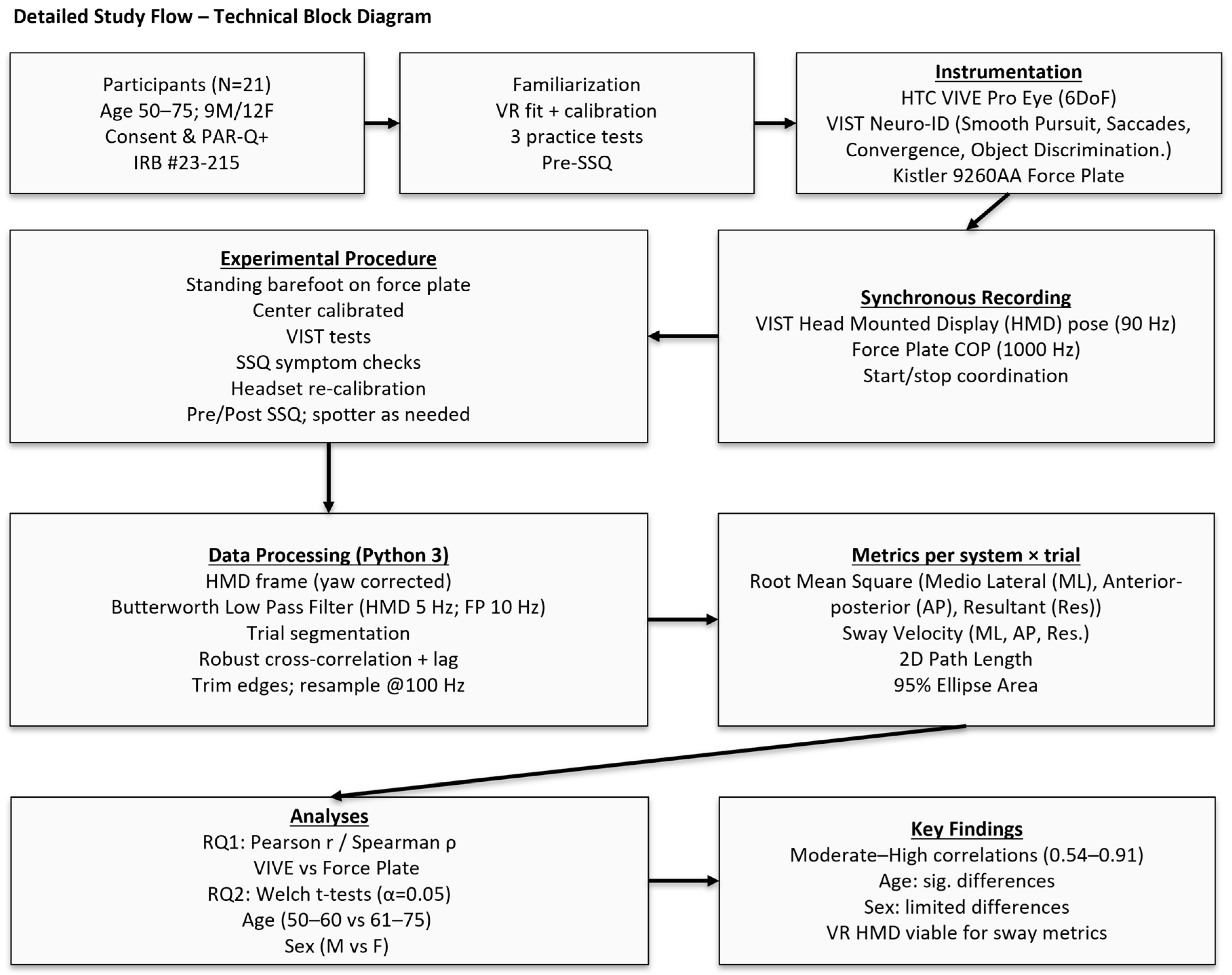

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size

2.2. Participants

2.3. Participant Screening and Preparation

2.4. Instrumentation

2.4.1. VR Headset and VIST Neuro-ID Platform

2.4.2. VIST Neuro-ID Test Battery

2.4.3. Kistler Force Plate Hardware and Signal Conditioning

2.5. Experimental Setup and Calibration

2.5.1. Force Plate Setup

2.5.2. HTC Vive Setup

2.6. Familiarization

2.7. Experimental Procedures

2.8. Data Preprocessing

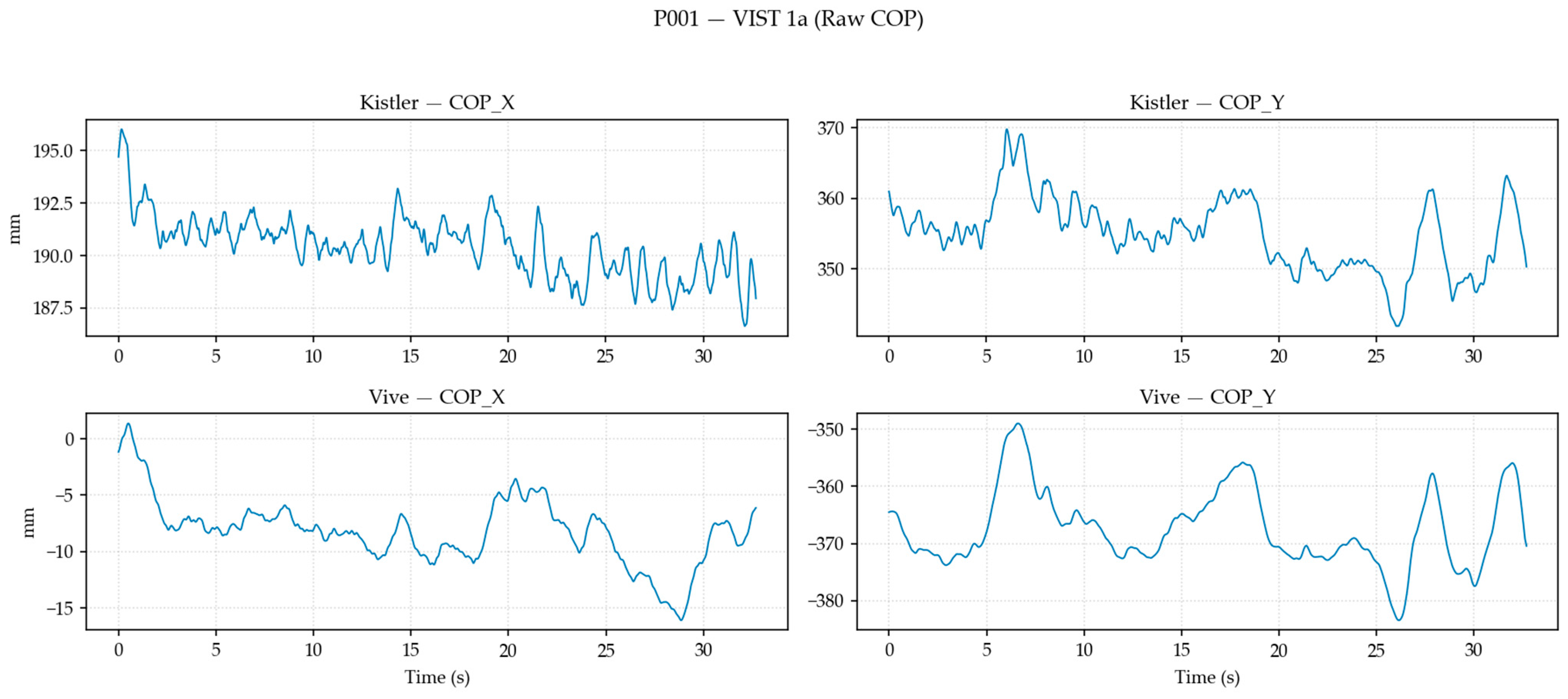

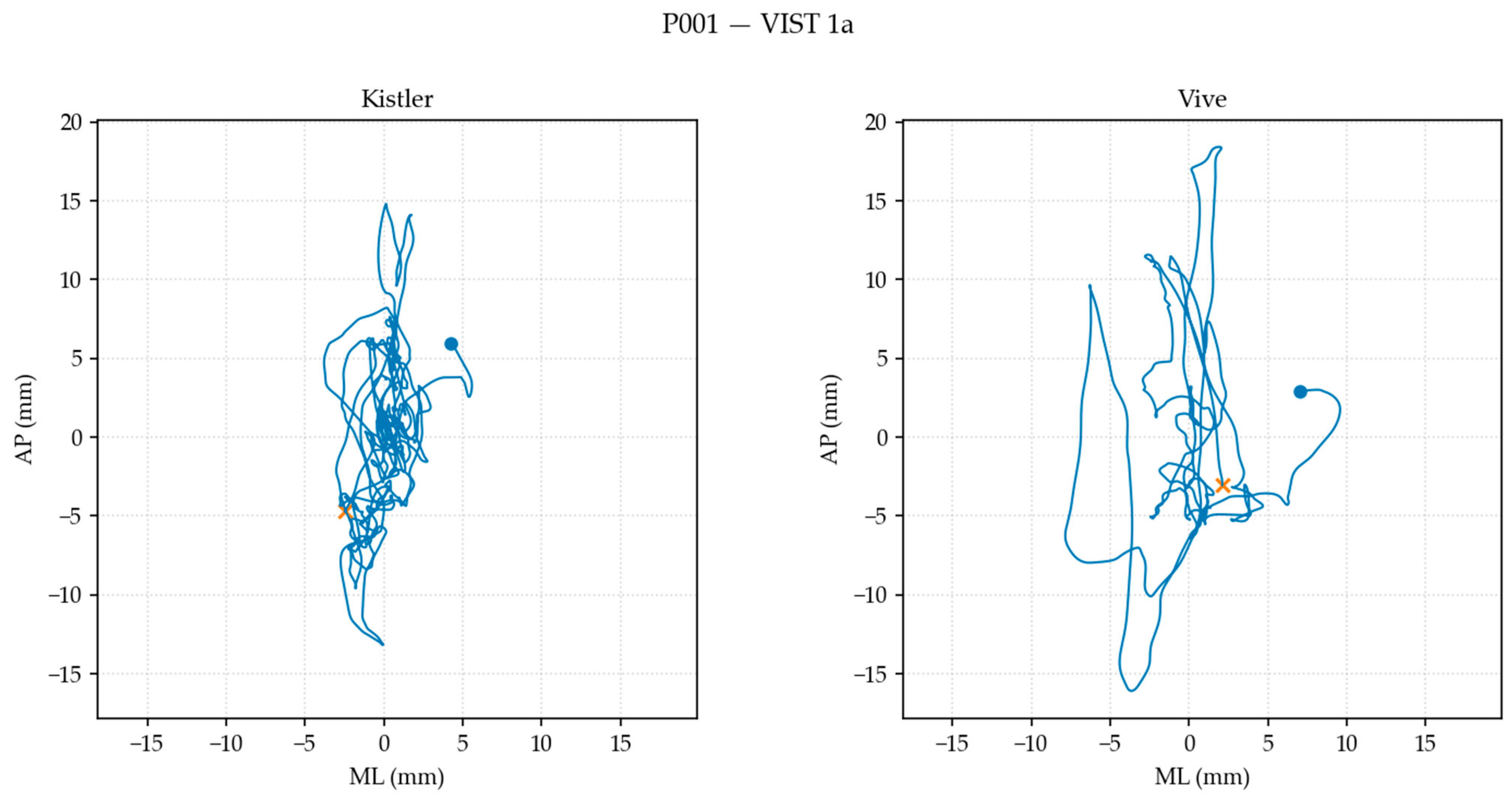

2.8.1. Data Transformation, Filtering, and Alignment

2.8.2. Postural Sway Metric Computation

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. System Correlation (RQ1)

4.2. Population-Specific Comparison (RQ2)

5. Conclusions

5.1. Future Work

5.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VR | Virtual reality |

| VIST Neuro-ID | Virtual Immersive Sensorimotor Test for Neurological Impairment Detection |

| ML | Medio-lateral |

| AP | Anterior–posterior |

| COP | Center of pressure |

| HTC | High Tech Computer Corporation |

| HMD | Head-mounted display |

Appendix A

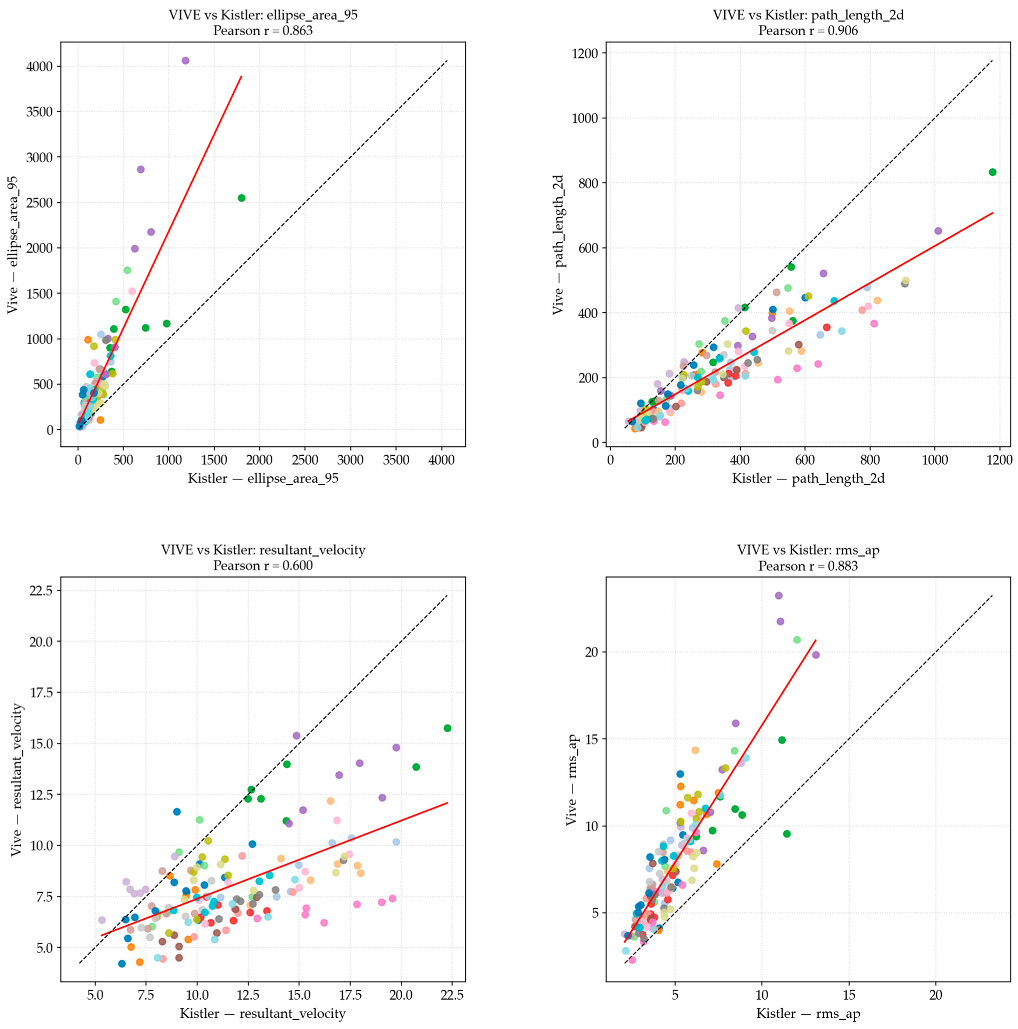

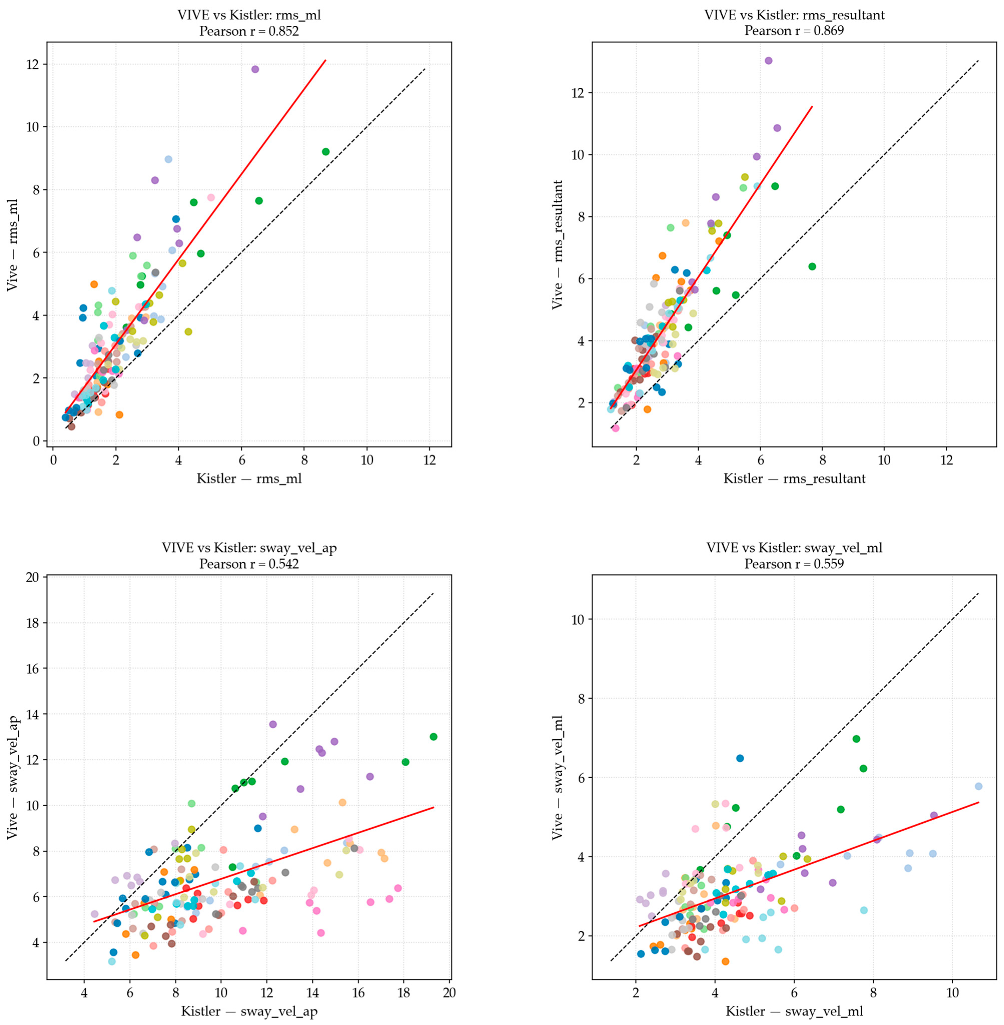

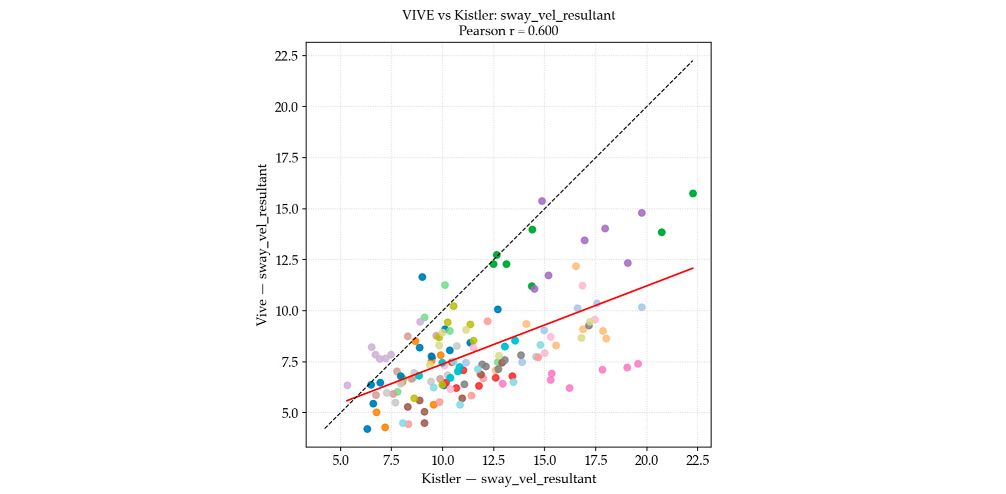

Appendix A.1. RQ1 Correlation Plots

Appendix A.2. RQ2 Bar Plots for Age Comparisons

Appendix A.3. RQ2 Bar Plots for Sex Comparisons

References

- World Health Organization. Falls [Fact Sheet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Lo, P.Y.; Su, B.L.; You, Y.L.; Yen, C.W.; Wang, S.T.; Guo, L.Y. Measuring the Reliability of Postural Sway Measurements for a Static Standing Task: The Effect of Age. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 850707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein, L.Z. Falls in older people: Epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing 2006, 35 (Suppl. S2), ii37–ii41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumway-Cook, A.; Woollacott, M.H. Motor Control: Translating Research into Clinical Practice, 5th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Waltham, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Horak, F.B. Postural orientation and equilibrium: What do we need to know about neural control of balance to prevent falls? Age Ageing 2006, 35 (Suppl. S2), ii7–ii11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Porta, F.; Caselli, S.; Susassi, S.; Cavallini, P.; Tennant, A.; Franceschini, M. Is the berg balance scale an internally valid and reliable measure of balance across different etiologies in neurorehabilitation? A revisited rasch analysis study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, T.E.; Myklebust, J.B.; Hoffmann, R.G.; Lovett, E.G.; Myklebust, B.M. Measures of postural steadiness: Differences between healthy young and elderly adults. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1996, 43, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.J.; Kanekar, N.; Aruin, A.S. The role of anticipatory postural adjustments in compensatory control of posture. Natl. Libr. Med. 2010, 20, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikó, I.; Szerb, I.; Szerb, A.; Poor, G. Effectiveness of balance training programme in reducing the frequency of falling in established osteoporotic women: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, F.B.; Wrisley, D.M.; Frank, J. The Balance Evaluation Systems Test (BESTest) to Differentiate Balance Deficits. 2009. Available online: www.ptjournal.org (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Palm, H.-G.; Johannes, S.; Gerhard, A. The role and interaction of visual and auditory afferents in postural stability. Natl. Libr. Med. 2009, 30, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Lee, K.; Lee, B.; Lee, H.; Lee, W. Relationship between Postural Sway and Dynamic Balance in Stroke Patients. Natl. Libr. Med. 2014, 26, 1989–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatman-Yates, C.C.; Lee, A.; Hugentobler, J.A.; Kurowski, B.G.; Myer, G.D.; Riley, M.A. Test-retest consistency of a postural sway assessment protocol for adolescent athletes measured with a force plate. Natl. Libr. Med. 2013, 8, 741. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24377060/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Sun, R.; Sosnoff, J.J. Novel Sensing Technology in Fall Risk Assessment in Older Adults: A Systematic Review; BioMed Central Ltd.: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijoux, F.; Vienne-Jumeau, A.; Bertin-Hugault, F.; Zawieja, P.; Lefevre, M.; Vidal, P.P.; Ricard, D. Center of pressure displacement characteristics differentiate fall risk in older people: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 62, 101117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, H.; Burch, R.F.; Talegaonkar, P.; Saucier, D.; Luczak, T.; Ball, J.E.; Turner, A.; Kodithuwakku Arachchige, S.N.K.; Carroll, W.; Smith, B.K.; et al. Wearable stretch sensors for human movement monitoring and fall detection in ergonomics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, P.; Fang, Y.; Wu, X.; Xie, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ren, H.; Jing, F. A Decade of Progress in Wearable Sensors for Fall Detection (2015–2024): A Network-Based Visualization Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reneker, J.C.; Pruett, W.A.; Babl, R.; Brown, M.; Daniels, J.; Pannell, W.C.; Shirley, H.L. Developmental methods and results for a novel virtual reality concussion detection system. Virtual Real 2025, 29, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.S.; Lane, N.E.; Berbaum, K.S.; Lilienthal, M.G. Simulator Sickness Questionnaire: An Enhanced Method for Quantifying Simulator Sickness. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 1993, 3, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijoux, F.; Nicolaï, A.; Chairi, I.; Bargiotas, I.; Ricard, D.; Yelnik, A.; Oudre, L.; Bertin-Hugault, F.; Vidal, P.-P.; Vayatis, N.; et al. A review of center of pressure (COP) variables to quantify standing balance in elderly people: Algorithms and open-access code*. Am. Physiol. Soc. 2021, 9, e15067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhe, A.; Fejer, R.; Walker, B. The test-retest reliability of centre of pressure measures in bipedal static task conditions—A systematic review of the literature. Gait Posture 2010, 32, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Xiong, S. Center-of-pressure based postural sway measures: Reliability and ability to distinguish between age, fear of falling and fall history. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2015, 47, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukaka, M.M. A guide to appropriate use of Correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med. J. 2012, 24, 69–71. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3576830/ (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Rosiak, O.; Puzio, A.; Kaminska, D.; Zwolinski, G.; Jozefowicz-Korczynska, M. Virtual Reality-A Supplement to Posturography or a Novel Balance Assessment Tool? Sensors 2022, 22, 7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittstein, M.W.; Crider, A.; Mastrocola, S.; Gonzalez, M.G. Use of virtual reality to assess dynamic posturography and sensory organization: Instrument validation study. JMIR Serious Games 2020, 8, e19580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylcott, B.; Lin, C.C.; Williams, K.; Hinderaker, M. Investigating the use of virtual reality headsets for postural control assessment: Instrument validation study. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2021, 8, e24950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.M.; Stafford, J.; Egorova, A.; McCabe, C.; Matthews, M. Can We Use the Oculus Quest VR Headset and Controllers to Reliably Assess Balance Stability? Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, N.L.; Brauer, S.; Nitz, J. Changes in Postural Stability in Women Aged 20 to 80 Years. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003, 58, M525–M530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riis, J.; Eika, F.; Blomkvist, A.W.; Rahbek, M.T.; Eikhof, K.D.; Hansen, M.D.; Søndergaard, M.; Ryg, J.; Andersen, S.; Jorgensen, M.G. Lifespan data on postural balance in multiple standing positions. Gait Posture 2020, 76, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.W.; Duncan, M.J.; Price, M.J. The emergence of age-related deterioration in dynamic, but not quiet standing balance abilities among healthy middle-aged adults. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 140, 111076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, V.; Bernetti, A.; Mangone, M.; Paoloni, M. Clinical definition of sarcopenia. Clin. Cases Miner. Bone Metab. 2014, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, B.E.; Holliday, P.J.; Topper, A.K. A Prospective Study of Postural Balance and Risk of Falling in An Ambulatory and Independent Elderly Population. J. Gerontol. 1994, 49, M72–M84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertes, G.; Baldewijns, G.; Dingenen, P.J.; Croonenborghs, T.; Vanrumste, B. Automatic fall risk estimation using the nintendo Wii Balance Board. In HEALTHINF 2015—8th International Conference on Health Informatics, Proceedings; Part of 8th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies, BIOSTEC 2015; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2015; pp. 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinc, Ž.; Löfler, S.; Hofer, C.; Carraro, U.; Šarabon, N. Diagnostic Balance Tests for Assessing Risk of Falls and Distinguishing Older Adult Fallers and Non-Fallers: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitabayashi, T.; Demura, S.; Yamaji, S.; Nakada, M.; Noda, M.; Imaoka, K. Gender Differences and Relationships between Physical Parameters on Evaluating the Center of Foot Pressure in Static Standing Posture. Equilib. Res. 2002, 61, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farenc, I.; Rougier, P.; Berger, L. The influence of gender and body characteristics on upright stance. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2003, 30, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, E.C.; Trew, M.E.; Bruce, A.M.; Kuisma, R.M.E.; Smith, A.W. Gender differences in balance performance at the time of retirement. Clin. Biomech. 2005, 20, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Addio, G.; Iuppariello, L.; Pagano, G.; Biancardi, A.; Lanzillo, B.; Pappone, N.; Cesarelli, M. New posturographic assessment by means of novel e-textile and wireless socks device. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications, MeMeA 2016—Proceedings, Benevento, Italy, 15–18 May 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinfelder, S.; Durlak, F.; Barth, J.; Klucken, J.; Eskofier, B.M. Wearable static posturography solution using a novel pressure sensor sole. In Proceedings of the 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBC 2014, Chicago, IL, USA, 6 November 2014; pp. 2973–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federolf, P.; Kühne, M.; Schiel, K.; Reimeir, E.; Debertin, D.; Calisti, M.; Mohr, M. Validation of markerless (Theia3DTM) against marker-based (ViconTM) motion capture data of postural control movements analyzed through principal component analysis. J. Biomech. 2025, 189, 112831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Mini-Cog: A Cognitive ‘Vital Signs’ Measure for Dementia Screening in Multi-Lingual Elderly. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-12514-005 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

| VIST Neuro-ID Tests | Part ID | Test Description |

|---|---|---|

| Smooth Pursuits | 1a * | An object begins left of midline, moving to the right and back in a sinusoidal pattern at three different frequencies, moving at a constant velocity. |

| 1b * | Central object is displayed for fixation, and a moving object comes in from one side and moves in opposite direction, increasing velocity in a step-ramp pattern. | |

| Saccades | 2a * | A blue object appears in center of view, and, at random, a peripheral object appears to the left, right, above, or below the object. The participant must look in the direction of the object that appears. |

| 2b * | Similar to (2a), except the object is yellow, and the participant must look in the opposite direction of where the object appears. | |

| 2c * | Functions as a combination of (2a) and (2b), where participant will have to respond to a blue or yellow object according to the previous subcomponents. | |

| Convergence | 3 * | An object starts in the center of view, appearing to be distant, while slowly moving towards the participant’s eyes at a constant speed. This is repeated three times. |

| Peripheral Vision | 4 | A center object is displayed along with three objects along each side—all unique shapes and colors. The central object changes to match one of the other objects until selection is made with the controller. The participant is instructed to keep their focus on the center throughout the test. |

| Object Discrimination | 5 * | Two T-shaped objects with different trunk lengths are displayed side-by-side, and the trunk lengths are then quickly concealed. Participants are instructed to keep their focus on the object with the longer trunk. |

| Gaze Stability | 6a | A 3D object is displayed in the center, and the participant is instructed to shake their head left and right while focusing on the object to the sound of a metronome at 180 beats per minute for ten repetitions. |

| 6b | Similar to (6a), except the participant shakes their head up and down. | |

| Head–Eye Coordination | 7 | Object appears in a random order in four corners of the virtual environment, disappearing and re-appearing randomly in different corners. The participant is instructed to follow the object with both their eyes and head. |

| Cervical Neuromotor Control | 8 | A target is displayed with the head in midline, a circle is drawn around the center as the participant keeps their focus on the center of the target. Once the circle completes, the screen will turn dark and the participant is instructed to turn their head right, left, or into extension until they see a blue object. When returning to midline, the participant presses the button on the controller to reveal the target and repeat the process. This process is completed three times in each direction. |

| Metric Name | Computation/Formula |

|---|---|

| Root-mean-square (RMS) ML [7] | Root-mean-square calculation of mean-centered time series data in ML direction |

| RMS AP [7] | Root-mean-square calculation of mean-centered time series data in AP direction |

| RMS resultant [7] | Root-mean-square calculation of mean-centered time series data of 2D resultant vector |

| Sway velocity ML [21] | |

| Sway velocity AP [21] | |

| 2D path length [7,22] | |

| Resultant velocity [21,22] | Path length divided by total duration |

| 95% ellipse area (mm2) [7] | Using covariance ∑ of [ML, AP], ×× |

| Postural Sway Metric | Pearson’s r Correlation (Linear) | Spearman’s ρ Correlation (Rank-Based) | Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMS ML | 0.852 | 0.824 | High |

| RMS AP | 0.883 | 0.879 | High |

| RMS Resultant | 0.869 | 0.857 | High |

| Sway Velocity ML | 0.559 | 0.523 | Moderate |

| Sway Velocity AP | 0.542 | 0.521 | Moderate |

| 2D Path Length | 0.906 | 0.920 | Very high |

| Resultant Velocity | 0.600 | 0.554 | Moderate |

| 95% Ellipse Area | 0.863 | 0.855 | High |

| Comparison | System | Metric | t | p | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (M vs. F) | Kistler | RMS ML | 0.027 | 0.979 | |

| Kistler | RMS AP | −1.912 | 0.058 | ||

| Kistler | RMS Resultant | −1.697 | 0.092 | ||

| Kistler | Sway Velocity ML | 0.992 | 0.323 | ||

| Kistler | Sway Velocity AP | −3.495 | 0.001 | ** | |

| Kistler | 2D Path Length | −1.115 | 0.267 | ||

| Kistler | Resultant Velocity | −2.652 | 0.009 | * | |

| Kistler | 95% Ellipse Area | −0.392 | 0.696 | ||

| HTC Vive | RMS ML | 0.558 | 0.578 | ||

| HTC Vive | RMS AP | −2.022 | 0.046 | * | |

| HTC Vive | RMS Resultant | −2.206 | 0.029 | * | |

| HTC Vive | Sway Velocity ML | 0.293 | 0.77 | ||

| HTC Vive | Sway Velocity AP | −0.704 | 0.483 | ||

| HTC Vive | 2D Path Length | −0.104 | 0.918 | ||

| HTC Vive | Resultant Velocity | −0.547 | 0.585 | ||

| HTC Vive | 95% Ellipse Area | −0.815 | 0.417 |

| Comparison | System | Metric | t | p | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Ranges (50–60 years old vs. 61–75 years old) | Kistler | RMS ML | −6.988 | <0.001 | *** |

| Kistler | RMS AP | −3.310 | 0.001 | ** | |

| Kistler | RMS Resultant | −3.694 | <0.001 | *** | |

| Kistler | Sway Velocity ML | −4.316 | <0.001 | *** | |

| Kistler | Sway Velocity AP | −2.788 | 0.006 | ** | |

| Kistler | 2D Path Length | −1.542 | 0.125 | ||

| Kistler | Resultant Velocity | −3.616 | <0.001 | *** | |

| Kistler | 95% Ellipse Area | −5.061 | <0.001 | *** | |

| HTC Vive | RMS ML | −7.551 | <0.001 | *** | |

| HTC Vive | RMS AP | −3.490 | 0.001 | ** | |

| HTC Vive | RMS Resultant | −3.465 | 0.001 | ** | |

| HTC Vive | Sway Velocity ML | −5.816 | <0.001 | *** | |

| HTC Vive | Sway Velocity AP | −5.384 | <0.001 | *** | |

| HTC Vive | 2D Path Length | −2.619 | 0.01 | * | |

| HTC Vive | Resultant Velocity | −6.132 | <0.001 | *** | |

| HTC Vive | 95% Ellipse Area | −5.300 | <0.001 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saucier, D.; McDonald, K.; Mydlo, M.; Barber, R.; Wall, E.; Derby, H.; Reneker, J.C.; Chander, H.; Burch, R.F.; Weinstein, J.L. Validating a Wearable VR Headset for Postural Sway: Comparison with Force Plate COP Across Standardized Sensorimotor Tests. Electronics 2025, 14, 4156. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214156

Saucier D, McDonald K, Mydlo M, Barber R, Wall E, Derby H, Reneker JC, Chander H, Burch RF, Weinstein JL. Validating a Wearable VR Headset for Postural Sway: Comparison with Force Plate COP Across Standardized Sensorimotor Tests. Electronics. 2025; 14(21):4156. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214156

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaucier, David, Kaitlyn McDonald, Michael Mydlo, Rachel Barber, Emily Wall, Hunter Derby, Jennifer C. Reneker, Harish Chander, Reuben F. Burch, and James L. Weinstein. 2025. "Validating a Wearable VR Headset for Postural Sway: Comparison with Force Plate COP Across Standardized Sensorimotor Tests" Electronics 14, no. 21: 4156. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214156

APA StyleSaucier, D., McDonald, K., Mydlo, M., Barber, R., Wall, E., Derby, H., Reneker, J. C., Chander, H., Burch, R. F., & Weinstein, J. L. (2025). Validating a Wearable VR Headset for Postural Sway: Comparison with Force Plate COP Across Standardized Sensorimotor Tests. Electronics, 14(21), 4156. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214156