Abstract

Time series forecasting (TSF) is gaining significance in various applications. In recent years, many pre-trained large language models (LLMs) have been proposed, and some of them have been adapted for use in TSF. When applying LLMs to TSF, existing strategies with complex adapters and data preceding modules can increase training time. We introduce StreamTS, a highly streamlined time series forecasting framework built upon LLMs and decomposition-based learning. First, time series are decomposed into a trend component and a seasonal component after instance normalization. Then, a pre-trained LLM facilitated by the proposed BC-Prompt is used for future long-term trend prediction. Concurrently, a linear model simplifies the fitting of future short-term seasonal term. The predicted trend and seasonal series are finally added to generate the forecasting results. In our efforts to achieve zero-shot forecasting, we replace the linear prediction part with a statistical learning method. Extensive experiments demonstrate that our proposed framework outperforms many TSF-specific models across various datasets and achieves significant improvements over LLM-based TSF methods.

1. Introduction

Time series are ubiquitous in today’s data-driven world [1]. Time series forecasting (TSF), as a task of predicting future variations of time series data, has been widely applied in various domains, such as energy computation, transportation, economic planning, and weather forecasting [2]. During the past several decades, TSF solutions have undergone a progression from traditional statistical methods (e.g., Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average Model (ARIMA) [3]) and machine learning techniques (e.g., GBRT [4]) to deep learning-based solutions, e.g., Recurrent Neural Networks [5] and Temporal Convolutional Networks [6,7]. Deep learning methods have demonstrated significant advantages in various TSF tasks; however, these methods are usually task-specific, meaning that when applied to new data or new tasks, they often need to be trained from scratch. Foundation large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 [8], LLaMA [9], and others [10] have demonstrated strong generalization and applicability across a wide range of computer vision (CV) and natural language processing (NLP) tasks, often by fine-tuning only a small portion of their architecture. With the remarkable progress of LLMs in the fields of CV and NLP, researchers have begun to explore their applications in time series tasks and have achieved promising results, such as TimesFM [11], One Fits All [12], and AutoTimes [13]. For LLMs designed to handle visual tasks, their ability to process different modalities (text and images/videos) primarily stems from training on Internet-scale text and image corpora. However, despite the vast quantities of time series data generated daily (e.g., from physiological recordings or wearable sensors), only a small portion is publicly available due to privacy regulations (e.g., HIPAA), and such data is far from sufficient to train an LLM-based framework from scratch [14]. As a result, LLM-based time series models often fall short of specialized TSF models (e.g., FiLM [15]) in terms of accuracy and training efficiency. These challenges highlight the limitations of applying LLMs directly to time series tasks, particularly in data-scarce or privacy-sensitive domains. How to eliminate the effort of utilizing LLMs to achieve high accuracy of TSF is worth studying.

At present, TSF methods based on foundation LLMs typically adopt a frozen pre-trained LLM as the core, supplemented by prompt-based encoding [16] and fine-tuning of a small set of learnable parameters to achieve semantic alignment of time series data and to establish the mapping between features and forecasting tasks [12]. However, the LLM models are all Transformer variants based on self-attention mechanisms and are greatly dependent on the information provided previously to achieve the next information generation [17]. As noted in [18], Transformer methods face challenges in handling temporal fluctuations and heterogeneity between variables; this profoundly influences the computation of attention in subsequent analyses. How to enable LLMs to adapt to the high volatility of temporal variations and heterogeneity among variables remains a key challenge to address.

We argue that reducing the volatility of time series can effectively improve the prediction accuracy of LLMs, as LLMs possess strong contextual memory and long-term feature learning capabilities, making them more suitable for capturing overall trends in time series. Building on this idea, we propose StreamTS, a simple yet effective solution for constructing an LLM-based time series forecaster through lightweight adaptation. Specifically, we first decompose time series into simple trend and seasonal components to ease the forecasting process. Then, the LLM is employed to predict the general variations of the time series (trend component), while a linear model is used to capture dramatic short-term fluctuations (seasonal component) [19]. In addition, we design a BC-Prompt by integrating background knowledge and Chain-of-Thought (CoT) [20], which effectively guides LLMs to achieve more accurate trend forecasting through simple prompting. In the StreamTS framework, we keep the pre-trained LLM weights frozen and only train a small linear module, which greatly reduces the number of trainable parameters. For zero-shot forecasting, the goal is to enabling the LLM’s ability to generalize across various TSF tasks without any task-specific fine-tuning. To this end, we explore the feasibility of achieving zero-shot forecasting by integrating the StreamTS framework with traditional statistical methods. Concretely, we replace the linear module with ARIMA. With no additional training, the TSF inference can be performed directly. This design further highlights that our method is well suited for data-scarce or unknown application scenarios and can effectively address the challenges faced by LLM-based time series forecasting methods in handling data volatility and heterogeneity.

Extensive experimental results validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, demonstrating its superior performance compared with various state-of-the-art deep learning models for time series forecasting. In particular, it shows notable advantages in few-shot forecasting tasks, where deep learning methods often struggle. The proposed StreamTS provides a scalable paradigm that enables LLMs to generalize and acquire task-specific competencies beyond those attained in their original pre-training. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- We propose a simple and efficient LLM-based time series forecasting model, StreamTS. Built upon the idea of time series decomposition, the model leverages the reasoning capability of LLMs to capture long-term trends while employing a lightweight linear module to predict seasonal patterns. This design significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters and achieves outstanding performance across multiple evaluation metrics.

- (2)

- The proposed BC-Prompt module integrates background knowledge with the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) approach, guiding LLMs to focus on one step at a time, which greatly enhances forecasting accuracy.

- (3)

- Our model’s performance consistently reaches the state of the art in mainstream forecasting tasks, particularly in few-shot scenarios. It even performs well in zero-shot forecasting. Therefore, our study represents a substantial advancement in uncovering the untapped potential of LLMs for time series analysis and other sequential data applications.

2. Related Work

2.1. Time Series Forecasting

As the importance of time series forecasting (TSF) increases, various models have been well developed. This goes back to ARIMA, which uses autoregression to make predictions that tackle the forecasting problem by transforming the non-stationary process to stationary through differencing [2]. In addition, some models handle temporal problems with the help of complex neural networks, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [21], Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) [22] and Gate Recurrent Unit (GRU) [10,23]. When the self-attention mechanism was released [24], it was quickly applied to TSF with the emergence of various models. Representatively, LogTrans [25] uses sparse design to capture local information and reduce the space complexity theoretically. Autoformer [2] borrows the ideas of decomposition and auto-correlation from traditional time series analysis methods. FEDformer [26] uses Fourier-enhanced structure to improve computational efficiency and gain linear complexity [27]. Recently, LLMs based on Transformer show great potential in many fields, such as NLP, CV, and audio processing. For TSF, models such as TimesFM [11] and One Fits All [12] are specially designed. However, they have shortcomings in the accuracy of timing prediction and still have some room for improvement.

2.2. Decomposition of Time Series

After decades of development, sequence decomposition, as a standard procedure, has been widely used in TSF tasks. There are currently three main ideas. The additive model assumes the observed time series (TS) is the sum of components: trend and seasonality.

The multiplicative model (e.g., Seasonal-Trend decomposition using Loess (STL) [28]) assumes the observed time series is a product of its components: trend, seasonality, and residual.

Matrix decomposition treats time series as a matrix and factorizes it into low-rank factors. The TSF models incorporating time series decomposition have achieved good results; for example, Prophet [29] with trend–seasonality decomposition and N-BEATS [30] with basis expansion and DeepGLO [31] with matrix decomposition. Recently, DLinear [32] has demonstrated exceptional performance by using a decomposition block and a single linear layer for each trend and seasonal component. With this idea, we apply a decomposition module to decompose time series into relatively smooth trend terms and fluctuated seasonal terms. We utilize linear modules to forecast future season patterns while leveraging the robust reasoning abilities of LLMs to analyze trend components.

2.3. Fine-Tuning Methods

Fine-tuning a pre-trained LLM can bring large performance gains in downstream tasks. However, fully fine-tuning a large model leads to huge resource consumption. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) is then developed. By training a small set of parameters and preserving most of the large pre-trained model’s structure, PEFT saves time and computational resources [12]. The most popular PEFT approaches include Adapter-based (e.g., Adapter, CoDA), Low-Rank Adaptation (e.g., LoRA), prefix tuning, and prompt tuning. LoRA uses twin low-rank decomposition matrices to minimize model weights and reduce the subset of trainable parameters even further. AutoTimes [13] adopts LoRA tuning to reduce training overhead, while Time-MoE [33] relies on inserting adapter modules to achieve task-specific adaptation. Prefix-tuning is a lightweight technique designed for natural language generation tasks. Instead of updating the full set of model parameters, it introduces a small set of trainable continuous vectors—referred to as prefixes—which are prepended to the input of each transformer layer. These prefixes serve as task-specific prompts that steer the model’s behavior, while the pre-trained model weights remain entirely frozen. Prompt-tuning simplifies prefix-tuning and trains models by injecting tailored prompts into the input or training data. It improves the reasoning abilities of LLMs, allowing the model to focus on solving one step at a time, rather than having to consider the entire problem all at once. In this paper, the proposed StreamTS takes a different approach. After decomposing the sequence, only the season component requires linear forecasting, necessitating the fine-tuning of a minimal set of parameters.

3. Method

The task of TSF is to predict a future sequence of length O, given a historical sequence of length I, denoted as input-I-predict-O [2]. In the long-term forecasting setting, our objective is to extend the output horizon O as much as possible while keeping the input horizon I fixed.

Recent advances in attention-based architectures have demonstrated the effectiveness of self-attention in capturing long-range dependencies in sequential data [24,34]. LLMs are fundamentally built upon Transformer-style attention, inheriting both the strengths and the vulnerabilities of attention mechanisms. In a standard attention mechanism, each token representation is projected into a query vector and a key vector , where d denotes the feature dimension. The similarity between positions i and j is then computed as

which determines the attention weight assigned from token i to token j. However, when directly applied to raw time series, the variance of these dot-product similarities is often dominated by large-scale fluctuations, leading to unstable and diffuse attention distributions across tokens [35]. To mitigate this issue, we first decompose the sequence into trend and seasonal components, thereby reducing cross-scale interference in the representation space and stabilizing the allocation of attention weights. From an attention perspective, this step enhances the LLM’s ability to consistently focus on semantically relevant temporal patterns. Our empirical analyses (Section 4.6 Model Analysis) further confirm that decomposition can reduce the impact of extreme fluctuations on attention distributions, achieveing more interpretable alignment across time steps.

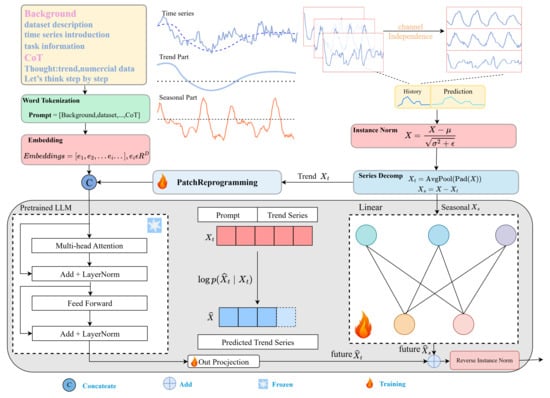

Building on this decomposition, we put the decomposed time series into an LLM model and a linear module to make full use of the LLM’s inference capability while a few parameters still need to be trained. The trend prediction of the LLM is further enhanced with the help of BC-Prompts. Figure 1 shows the overall framework.

Figure 1.

The overall architecture of the StreamTS model. Before decomposing a given time series, we first encode it with the help of patching and encoding layers. Season terms and trend terms are calculated through linear changes and pre-trained LLMs, respectively, to obtain corresponding results. The two parts are aligned and added together. Finally, a linear mapping is run to obtain the predicted results.

3.1. Input Preprocessing

A multivariate time series forecasting task can be defined as follows: given a multivariate , which contains M univariate series , the goal is to predict with . The forecasting model is optimized to minimize the prediction error over the entire prediction horizon T.

In our framework, the input sequence X is preprocessed through a reversible instance normalization operation [16]. Specifically, for each sample and each feature channel , we compute the mean and variance independently based solely on the input sequence, normalizing it to have zero mean and unit variance. This instance-wise, feature-wise normalization design ensures that no statistical information from the prediction horizon or other features is referenced, thereby strictly preventing data leakage. Such a strategy effectively mitigates distribution shifts across different time series while maintaining model generalization.

3.2. Decomposition

The goal of sequence decomposition is to extract the underlying trend and temporal patterns of a time series. Commonly used methods include classical Seasonal-Trend decomposition using Loess (STL) [28] and empirical mode decomposition (EMD) [36]. In contrast, we adopt a simple yet effective strategy: the trend component is obtained via a moving average smoothing, and the residual part is treated as the seasonal component. This lightweight approach ensures efficiency and interpretability while effectively capturing the essential dynamics required for LLM-based forecasting, especially in data-scarce scenarios. To simplify, let be the preprocessed input, then the specific decomposition is as follows:

where denote the seasonal and trend components, respectively. We adopt a centered moving-average smoothing filter with a window size w, denoted as . To ensure that the output length remains consistent with the input, replication padding is applied, where the boundary values are replicated to pad elements at both ends of the sequence before performing the moving average. In this way, the window size w directly controls the smoothness of the extracted trend, while the residual captures higher-frequency seasonal variations.

After this step, we use linear regression to fit the short-term season component and use pre-trained LLMs to predict long-term trend component. The two parts undergo different branch processing and are finally added to obtain the prediction result.

3.3. Linear Module

In order to improve performance, we use the direct multi-step strategy to predict variables to avoid the cumulative error caused by the iterated multi-step prediction [32]. Future forecasts are obtained by weighting historical data. For each univariate of the season component that comes from the decomposition, we predict the final value by a linear model; the mathematical expression is:

where is the weight vector. This operation is realized by a linear layer along the temporal axis.

3.4. BC-Prompt

In LLMs tuning, a prompt serves to guide the LLM model in understanding a task and controlling its output, enabling it to produce the desired behavior and results. A carefully designed prompt can reduce overfitting and help the model adapt to diverse downstream applications. Current prompting strategies can be generally categorized based on content (e.g., zero-shot and few-shot prompting), reasoning modes (e.g., Chain-of-Thought and Tree-of-Thoughts), and iterative approaches (e.g., retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) and Reasoning and Acting (ReAct)). For TSF tasks, zero-shot and few-shot prompts often fail to provide sufficient background information, while RAG and ReAct tend to introduce excessive temporal details, which may cause LLMs to overfit to noise rather than capturing the overall trend [37]. To address this issue, we propose the BC-Prompt template, which innovatively integrates domain-specific background knowledge of time series forecasting with the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) [38] reasoning paradigm. BC-Prompt consists of two core components: background knowledge and CoT reasoning, jointly guiding LLMs toward more accurate trend-oriented forecasting.

The background knowledge section includes three elements: (1) dataset description, which provides general information about the data source, collection method, and context; (2) time series introduction, which summarizes basic statistics of the input sequence such as the maximum, minimum, and median values, as well as the overall upward or downward trend. (3) task information, which defines the forecasting task, specifying the input and output lengths.

In the CoT reasoning part, we adopt a zero-shot CoT strategy and augment it with an explicit instruction to first infer the overall trend before engaging in numeric prediction. Specifically, the prompt begins by stating the goal of trend prediction, followed by a reasoning step where normalized values are computed. We then append the trigger phrase “Let’s think step by step.” This design encourages the LLM to form a coherent reasoning chain, starting from high-level trend understanding and gradually progressing toward fine-grained numerical estimation.

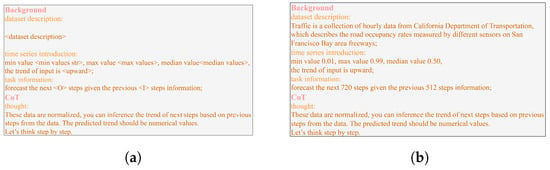

As shown in Figure 2a, we construct the prompts using a structured, JSON-like template. The dataset description is automatically selected according to the specific dataset, and the task information is automatically determined by the lengths of the input and output sequences. The time series introduction is derived from the statistical characteristics of the sequence. In particular, given a time series , its monotonic trend is simply determined by computing the Mann–Kendall statistic S (Equations (7) and (8)) and checking whether the S is positive or negative, corresponding to an upward or downward trend, respectively. This is easier than calculating linear regression slope and does not assume a normal distribution of data.

Figure 2.

An example of BC-Prompt. (a) BC-Prompt template. (b) BC-Prompt for Traffic dataset.

Once the template is filled out, the complete BC-prompt as shown in Figure 2b is provided to the LLM for inference. This automated pipeline ensures both the reproducibility and the flexibility of our approach across diverse datasets.

3.5. LLM Forecasting

The pre-trained LLM is in charge of trend prediction. It takes a combination of input from the BC-prompt and the decomposed trend sequence.

This textual BC-prompt needs to be converted into tokens and then embedded into vectors before it can be combined with the numerical sequence. For BC-prompt token :

where , P is the length of prompt tokens and D is consistent with the dimension of the LLM. Embed is the embedding operation.

Since LLMs are language-based models, using LLMs to perform a TSF task requires the process of converting the time series data into numerical language sequences. We adopt Patch Reprogramming [16] to align multivariate time series with the modality of natural language. Specifically, the operation of Patch Reprogramming PatchRep first transforms the input time series into a patch-level representation through a learnable patch embedding module. These patch embeddings are then aligned with a set of learnable text prototypes via a multi-head attention mechanism to facilitate modality alignment between numerical and textual inputs. Finally, the aligned representations are projected through a linear layer into the token space of the LLM. This process reformats structured time series into pseudo-linguistic embeddings, allowing compatibility with frozen LLMs without updating their internal weights.

where , I is the historical time series length and D is the required dimension of the LLM. The embedded prompts concatenating the decomposed trend terms are the input of the parameters-frozen LLMs, which can greatly improve the accuracy and reduce computational consumption.

The embedding trend series with its embedding prompt is processed to forecast the future trend by the following equations:

where denotes the predicted future trend of the input time series and concat is concatenation.

Although many LLMs have only the decoder part, the autoregressive approach is utilized to generate the subsequent steps, and the generated current prediction can be used as a reference for the next prediction. We use the known trend values to find the future trend values; the underlying logic is to use the known information to calculate the maximum conditional probability to find the next embeddings; these embeddings will be added to the previously known value to find the next value.

After reaching the prediction length, we will adopt Projection(·): to independently projects embeddings to numerical data.

The linear prediction and the LLMs prediction work in parallel. Corresponding to the time series decomposition, the predicted season output and the trend output obtained by the two parallel operations will be added together to obtain the final output . Afterward, the reverse instance normalization is applied to restore the forecasted sequence to its original scale using the same statistical parameters (mean and variance) computed from the input sequence. To ensure numerical stability during both normalization and inverse transformation, a small constant is added to the denominator when computing the standard deviation.

4. Experiments and Result Analysis

4.1. Experimental Settings

To validate the effectiveness of this framework, we conducted comprehensive experiments on six different datasets including mechanical systems (ETT), energy (Electricity), traffic (Traffic), Weather (Weather), economics (Exchange), and disease (ILI). These datasets are publicly available and have been extensively utilized for TSF [2]. The datasets were partitioned into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:1:2 ratio, following the chronological order of the time series.

In the implementation of our StreamTS, we adopted deepseek-math-7b-rl as the trend backbone and a fully connected layer as the linear model for season series prediction. The deepseek-math-7b-rl is a relatively small LLM model and is used to serve as the base model for the Top4 team at the Artificial Intelligence Mathematical Olympiad (AIMO).

We compared StreamTS with the latest models for TSF, including the linear-based model DLinear [32], the CNN-based models TimesNet [39] and MICN [40], the Transformer-based models PatchTST [27], Autoformer [2], and Nonstationary [41], and frequency-based model FiLM [15]. To ensure a fair comparison, we adhered to the experimental configurations across all models with a unified training pipeline. All deep learning models were implemented in PyTorch 2.2.2 and trained on NVIDIA A100 80 GB. The Adam optimizer was used with decay rates , and initial learning rates were selected from . We adopted a cosine annealing learning rate schedule with and . Batch size was set to 16. In our model, the patch size of Patch Reprogramming was set to 16, and the window size for decomposition was fixed at 25, following the setting in Autoformer to ensure fairness in experimental comparisons.

The experiments were designed from six perspectives: (1) full-shot forecasting, assessing the performance of the models in predicting different time lengths when using the entire training set; (2) few-shot forecasting, verifying the model’s performance using of the training set; (3) zero-shot forecasting, demonstrating the potentials of StreamTS in TSF without training any parameters; (4) comparisons with LLM time series models, analyzing its time efficiency compared to an advanced LLMs-based time series forecasting model; (5) model analysis, analyzing the attention mechanism of LLM Underlying Operations, assessing effects of time series decomposition; (6) parametric analysis, exploring the impact of input length. Each experiment was repeated twice on the test sets to ensure the accuracy of experimental results. MAE and MSE were used as the evaluation metrics. A lower MAE/MSE indicates better performance of the model.

4.2. Full-Shot Forecasting

All of the models take the input time series length L = 512 and the prediction length for the ILI dataset and for other datasets.

The experimental results are presented in Table 1. Overall, StreamTS achieves the best aggregate performance across the six datasets, winning 34 out of 50 comparative evaluations. In terms of average MAE/MSE, our model ranks first or second on most datasets, except for the Electricity dataset. Specifically, among the Transformer-based models, patchTST achieves SOTA performance in TSF, while our model’s average MSE across six datasets is lower than it by . Similarly, compared to the linear-based model DLinear and CNN-based model TimesNet, our model achieves a reduction of and , respectively, on the average MSE. FiLM beats other models by eight times.

Table 1.

Full-shot forecasting task. We set the input length L = 512 and the prediction length T ∈ {24, 36, 48, 60} for ILI and T ∈ {96, 192, 336, 720} for others. Bold: best, underlined: second best.

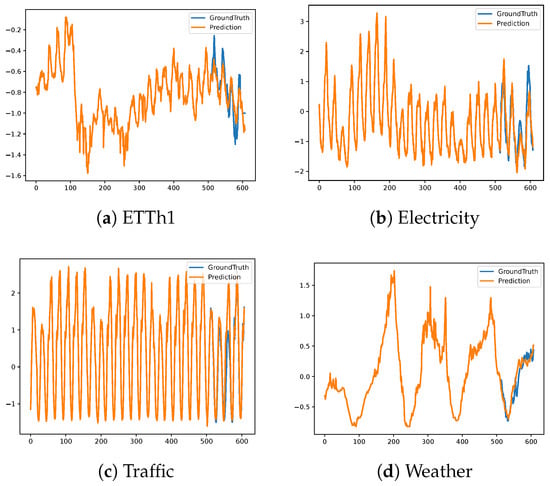

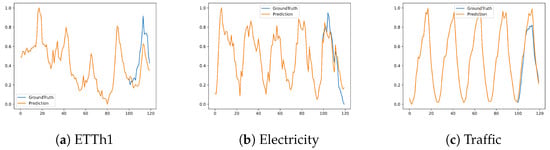

On the ILI and Exchange datasets, where the temporal dynamics are highly volatile, our current sliding-average decomposition with a fixed window size struggles to effectively capture the periodic patterns, leading to weaker forecasting performance. FiLM adopts a frequency-domain perspective and incorporates denoising strategies, which allow it to better extract essential temporal patterns and achieve more robust long-term forecasts under such challenging conditions. Inspired by this, exploring frequency-domain decomposition as an alternative or complementary approach represents a promising direction for our future work. In Figure 3, we visualize the full-shot forecasting results by StreamTS on four datasets with different data characteristics. The visualizations reveal that the predicted values closely match the ground truth, suggesting high accuracy across diverse scenarios.

Figure 3.

Full-shot forecasting cases from StreamTS on different datasets under the input-512-predict-96 settings. Blue lines are the ground truths and orange lines are the model predictions.

4.3. Few-Shot Forecasting

Compared with full-shot forecasting, few-shot forecasting allows us to verify the performance of models trained on a very small amount of data. Using 10% of the training data, the ILI dataset cannot be used because its series length is too short to constitute a complete test case after division by 10. The same is true for the Exchange dataset with a prediction step of 720. We show the few-shot forecasting results of five public datasets in Table 2. StreamTS outperforms other models 28 times out of 50 evaluations. On the Exchange dataset, our model achieves MSE reduction compared with the second best model PatchTST. On the Weather dataset, our model gains average MSE reduction compared with the second best DLinear. On the Traffic dataset, our model also surpasses other models, and shows greater long-term forecasting capacity.

Table 2.

Few-shot forecasting task learning with only 10% of the training data. We set the input length L = 512 and the prediction length T ∈ {96, 192, 336, 720} for all the datasets. Bold: best, underlined: second best.

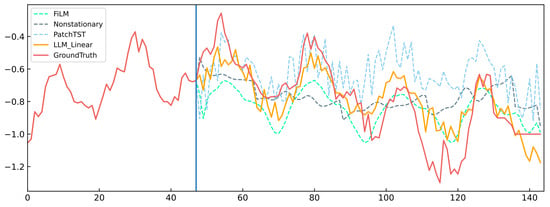

In Figure 4, we demonstrate the forecasting results of four models on the ETTh1 dataset, which shows only the 48 steps of the input and the full steps of prediction. From the figure, it is clear that the FiLM can well capture the periodicity in the time series, but it cannot follow the overall downward trend of the data, and it is too smooth to capture local variations. In contrast, the predictive output of PatchTST fluctuates drastically, exhibiting pronounced ups and downs. The Nonstationary curves show minimal change and resemble a straight line. Our model, however, demonstrates a better fit in the predictive component.

Figure 4.

Few-shot forecasting cases for different models on the ETTh1 dataset under the input-512-predict-96 settings.

4.4. Zero-Shot Forecasting

Zero-shot forecasting refers to the task of applying a forecaster trained on a source dataset directly to an unseen target dataset, without any additional training or fine-tuning [13]. Recent research on LLM-based TSF have to some extent explored the potential of LLMs as effective zero-shot reasoners. They often evaluate the zero-shot forecasting ability in transfer settings where the source and target datasets share similar temporal or domain characteristics, e.g., Time-LLM [16] was trained on ETTh1 and tested on ETTh2. Such a setting, involving only a minor shift in data distribution, embeds implicit domain knowledge and thus offers limited insight into the true generalization capabilities of these models.

To address this limitation, we propose a more rigorous and practical setting of zero-shot time series forecasting by directly leveraging pre-trained LLMs without any task-specific training. Our approach relies purely on the pretraining knowledge embedded in LLMs and does not involve gradient-based learning on time series data. This design is particularly valuable in real-world scenarios where access to reliable, relevant, and well-structured domain-specific data is limited. Building on this idea, we further introduce a hybrid method, LLM-ARIMA, for zero-shot time series prediction. As illustrated in Figure 1, the overall architecture remains unchanged; we only replace the Linear module with the traditional statistical method ARIMA, while all other components—including the Instance Norm, Series Decomp, BC-Prompt, LLM, Out Projection, and Reverse Instance Norm—are kept intact. LLM-ARIMA can leverage the language understanding capabilities of LLMs with the inductive bias of classical statistical models. To ensure full automation and maintain the inference-only nature of the pipeline, we apply an off-the-shelf statistical selection process to automatically determine the optimal ARIMA parameters (p, d, q) based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [3]. Without requiring any manual configuration or downstream fine-tuning, any trainable parameters are avoided. Our method pushes the boundary of zero-shot forecasting and explores the intersection of foundation models and traditional time series analysis.

To validate the feasibility of our proposed method, we conduct a series of experiments on widely recognized benchmark datasets in the field of TSF. Specifically, we select ETTh1, Electricity, and Traffic, which represent diverse temporal patterns and complexity levels, to ensure comprehensive evaluation across different real-world scenarios. For each dataset, we adopt a consistent evaluation protocol: the last 100 time steps are used as historical input, and the model is required to forecast the subsequent 20 steps (short horizons) and 50 steps (long horizons). This setting enables a fair comparison across models and highlights the robustness of our zero-shot framework under various data conditions.

Our method is compared against several strong baselines. First, we include GPT4S [1], an LLM-based method that applies prompt engineering for zero-shot forecasting. Second, we include classical time series forecasting models, ARIMA and Prophet. These comparisons provide a comprehensive understanding of how our LLM-based approach performs across traditional, neural, and hybrid paradigms under truly zero-shot conditions.

Table 3 shows the performance of each model for both short and long horizon prediction across various datasets. The results demonstrate that traditional statistical learning methods, when combined with pre-trained LLMs, can still achieve competitive results. In Figure 5, we present a visualization of the LLM_Arima predictions (i.e., LLM equipped with ARIMA), illustrating this synergy. These findings highlight the feasibility of applying LLMs in zero-shot time series forecasting scenarios.

Table 3.

Comparison of zero-shot forecasting performance across different models and datasets. Bold: best.

Figure 5.

The visualization of zero-shot forecasting results on different datasets under input-100-predict-20 settings; blue lines are the ground truths and orange lines are the model predictions.

4.5. Comparisons with LLM-Based Time Series Forecasting

Effect of LLM Variants. To assess whether the strong performance of the proposed StreamTS framework stems primarily from the choice of the underlying LLM, we conducted experiments using different pre-trained LLMs, paired with the same input and output modules. The compared models include DeepSeek-Math-7B-RL (the base LLM in our framework), DeepSeek-Math-7B-Instruct (a variant from the DeepSeek-Math family designed for broader knowledge coverage; we also replaced the base model in our framework with this variant), and Qwen2-0.5B-Instruct (a lightweight model from the Qwen2 family). Since the real-world changes we want to predict are drastically changing, the prediction can only be verified on datasets with irregular changes. For more difficult predicting tasks with irregular changes, we chose Exchange, a dataset that collects daily exchange rates for 8 countries from 1990 to 2016. These LLMs with a standard input–output module make predictions of 96, 192, 336, and 720 with an input length 512. The results are presented in Table 4, where Deepseek-rl refers to DeepSeek-Math-7B-RL, Deepseek-instruct corresponds to DeepSeek-Math-7B-Instruct, and Qwen2-instruct denotes Qwen2-0.5B-Instruct. StreamTS (Instruct) represents our proposed framework with DeepSeek-Math-7B-Instruct as the base LLM.

Table 4.

Comparison of predictions with different LLM models. Bold: best.

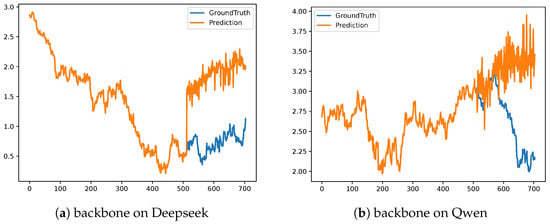

The performances of DeepSeek-Math-7B-RL and DeepSeek-Math-7B-Instruct are nearly identical, whether they are used as standalone LLM predictors or as the backbone within our framework. In contrast, Qwen2-0.5B-Instruct has a significantly different architecture from the DeepSeek-Math family. Nevertheless, all three LLM-only models are consistently outperformed by the full StreamTS framework. Figure 6 shows that both DeepSeek and Qwen models have a large deviation from the true value in the second half of the prediction. We conclude that just using a pre-trained LLM makes it difficult to make a good prediction for TSF tasks. Complex time series are often composed of multiple sub-sequences, and it is difficult for an LLM to make predictions of such complex sequences. For this reason, decomposing the time series into more smooth sequences will reduce the prediction difficulty of the LLM.

Figure 6.

The visualization of different LLMs’ forecasting results on exchange_rate datasets under input-512-predict-192 settings; blue lines are the ground truths and orange lines are the model predictions.

The consistent results between the math-focused model DeepSeek-Math-7B-RL and the more general-purpose DeepSeek-Math-7B-Instruct can be attributed to our use of Patch Reprogramming in the encoding stage, which maps time series data into natural language representations. As a result, the mathematical reasoning capabilities of DeepSeek-Math-7B-RL are not fully utilized in this context.

LLM-based TSF models. We compared StreamTS with some of the leading LLM-based TSF models: TIME-LLM [16], AutoTimes [13], One Fits All [12]. TIME-LLM stands out as a prominent example of these mainstream temporal LLMs. It does not need to fine-tune any of the layers in the LLM but introduces two learnable modules of Patch Reprogramming and Output Projection for the input and output processing. AutoTimes uses the LLM as an autoregressive time series predictor to allow arbitrary-length predictions with long-enough inputs and introduces LLM-embedded textual timestamps to enhance forecasting. One Fits All has a simple structure; however, it requires fine-tuning of the positional embeddings and layer normalization layers in the pre-trained language or image model.

For fair comparisons, TIME-LLM, AutoTimes, and One Fits All were also implemented using the Deepseek-math-7b-rl baseline LLM model. Table 5 shows the prediction performance of all the models. It clearly indicates that our StreamTS model achieves more accurate predictions on the ETTh1, Exchange, and Traffic datasets for various forecasting tasks. One Fits All is sometimes even worse than an LLM alone (e.g., on the Exchange dataset). This may be caused by the fine-tuning LLM layers with insufficient data. AutoTimes is unable to predict the output length 720 with the input length 512 due to its autoregressive model design, leaving the corresponding lines blank in Table 5. TIME-LLM performs much better than AutoTimes and One Fits All but consistently worse than our model.

Table 5.

Comparison of performance with the mainstream LLM-based TSF models. We set the input length . Bold: best.

The number of model parameters and the training speed (seconds per iteration, s/iter) are shown in Table 6. Since the LLM-based model takes up a large number of parameters, the total number of parameters in each model does not vary much. One Fits All and AutoTimes does not change the original model much and does not add too many modules, so the training speed is relatively fast. Compared to TIME-LLM, which has better prediction results, our model is much more sufficient in training with the average speed of 0.59 s/iter, which is about 68.6% of the time used by TIME-LLM. In StreamTS, we freeze the inference backbone without additional training and only need to train the linear forecasting component and the patch embedding. Despite having fewer training parameters, the accuracy of the predictions remains unaffected.

Table 6.

Comparison of efficiency with the mainstream LLM-based TSF models.

4.6. Model Analysis

In this section, we examine each part of the module carefully, from the original LLM prediction analysis to the final overall prediction effect.

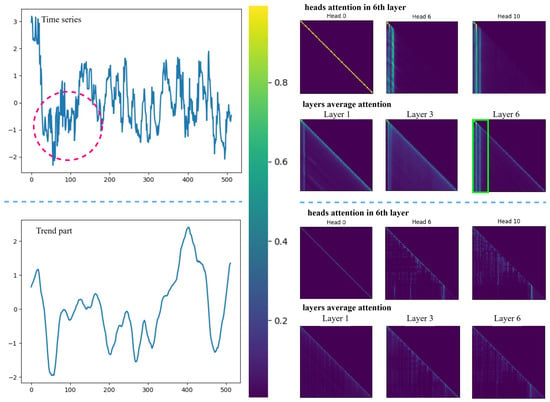

Model Interpretation. From Table 5, we can observe that using a pre-trained LLM directly for time series prediction is not as effective as our proposed LLM with time series decomposition. This motivates us to analyze the underlying reason. LLM is a self-attention-based network that utilizes autoregression to generate the next prediction value, and the previous values have a great impact on the later ones. Ref. [12] has proved that self-attention performs a function closely related to principle component analysis (PCA). However, PCA is known to be sensitive to data distribution and outliers. We take a time series from the ETTh1 dataset as an example and demonstrate the effect of before and after data in a sequence in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

A showcase of attention distribution.

The left side of Figure 7 displays the original sequence and its decomposed trend component from top to bottom, while the right side shows the corresponding attention distribution maps generated in the 1st, 3rd, and 6th layers and the multiple heads (0, 6, and 10) for the 6th layer. We can observe dramatic changes in the original sequence (highlighted by a red circle in Figure 7), and these change are reflected in the attention maps, more intensively in the 6th layer (highlighted by a green box in Figure 7). Meanwhile, the trend sequence is smooth owing to a moving average operation. The corresponding attention maps show the trend well eliminates the influence of local noise.

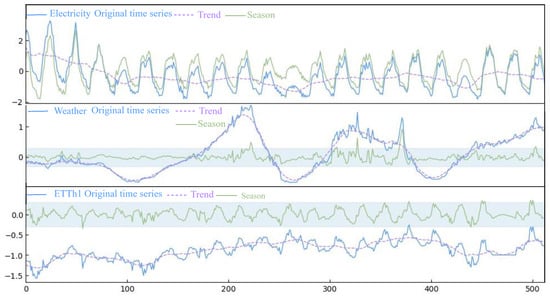

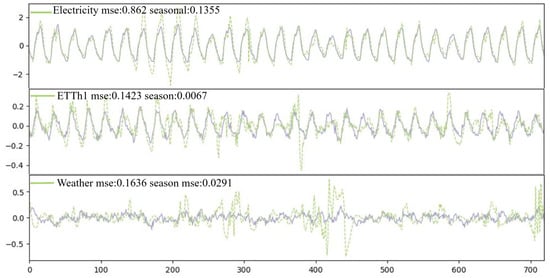

Time series decomposition and its effects. In Figure 8, we visualize the results of time series decomposition for three datasets. The Electricity dataset features short and relatively regular change cycles, the Weather dataset shows periodicity on larger timescales, while the ETTh1 dataset lacks clear patterns of change. After decomposition of the complex time series into trend and seasonal components, the LLM is used for long-term trend prediction, and the linear model is used for local seasonal fitting. The time series in the Electricity dataset exhibits inherent regularity, thus the decomposed seasonal series is more consistent in magnitude compared to the original series. The time series in the Weather dataset contains several cyclic peaks. After decomposition, the periodic is well captured by the trend, and the remaining seasonal series are reduced to a small range, which minimizes their interference in the prediction process. The decomposition of the time series of the ETTh1 dataset also produces a seasonal series within a small range around zero, which is better predicted by considering short-term influence.

Figure 8.

Time series decomposition on different datasets.

We demonstrate the linear model fits the seasonal series well in Figure 9. For the Electricity dataset, the linear model can accurately capture the waveforms, leading to a small MSE 0.1355 for the seasonal part. For the Weather and ETTh1 datasets, while there are some points where the linear model does not fit perfectly, it learns data patterns rather than overly responding to outliers. According to [19], simple linear layers have exceeded a complex self-attention mechanism for learning time dependency. This can be explained by the fact that time series variations can be highly influenced by the sequence order, while the attention mechanisms are permutation invariant on the temporal dimension.

Figure 9.

Seasonal series forecasting on different datasets under the input-512-predict-720 settings.

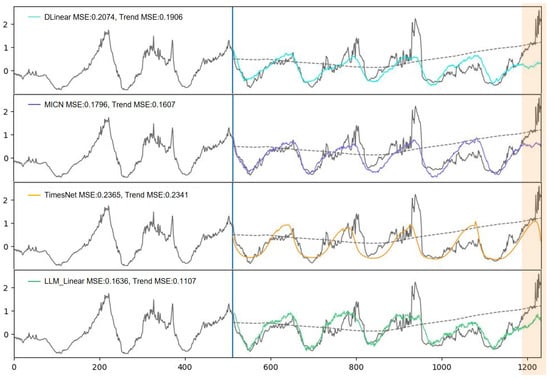

To examine the LLM capability for long-term trend prediction, we compare it with three other models, which represent linear, CNN-based, and Transformer-based models, respectively.

Figure 10 provides a qualitative result of the four different models by visualizing the prediction results for 720 steps in the Weather dataset. In the case of TimesNet, the error for trend prediction is high (MSE = 0.2341), leading to a higher overall prediction error (MSE = 0.2365). In particular, TimesNet predicts a downward ultimate trend (in the orange highlighted part), which is against the true upward trend.

Figure 10.

The forecasting results for the input-512- predict-720 setting on the Weather dataset, showing the long-term prediction performance of the models, DLinear, MICN, TimesNet, and StreamTS from top to bottom.

DLinear and MICN, although better at following long-term variations than TimesNet, struggle to capture high-frequency patterns effectively. Our model, on the other hand, successfully manages to capture both long-term variations and high-frequency patterns. This advantage can be attributed to the intricate design of our model’s architecture, which is tailored to capitalize on both season component and trend component predictions. From the results in Table 5, it is clear that the adapted model is significantly more effective in predicting compared to the LLM.

Ablation study

To validate the effectiveness of the components of StreamTS, BC-Prompt, and decomposition for time series, we conducted ablation studies on the ETTh1 and Exchange datasets. The results are shown in Table 7. It is evident that the prediction performance consistently declines when only the forecasting task information is kept in the prompts (w/o BC). The absence of decomposition (w/o DT) reduces the overall performance of the model. For the Exchange dataset that is more difficult to predict, the average drop is approximately 33% in MSE, 16% in MAE. The removal of BC-Prompt and decomposition (w/o P&DT) results in the most severe impact, preventing the LLM from effectively capturing the short-term changes of time series. For long-term forecasting (e.g., pred-720), however, the prediction errors are not serious. This further confirms that the LLM model is more capable of learning the general trend of time series.

Table 7.

Ablations study of the proposed model. We follow the protocol of AutoTimes ablation studies [13] to verify whether the LLM is truly useful in our StreamTS: (1) w/NoiseP randomly mask 10% of background in BC-Prompt tokens with “#”; (2) w/Prophet replace decomposition module with Prophet; (3) w/o BC replace the BC-Prompt with simply instructions (“Task description: forecast the next O steps given the previous I steps information;”); (4) w/o DT remove the linear part and keep the LLM with BC-Prompt; (5) w/o P&DT input the times series directly into the LLM. Bold: best.

To examine the robustness of prompts to noisy or incomplete background information, we introduced perturbations into the BC-Prompt background (w/NoiseP). Specifically, we randomly masked 10% of the background tokens in BC-Prompt with the symbol “#”. The results on the ETTh1 and Exchange datasets show only minor fluctuations, indicating that the model remains stable under such perturbations. In addition, we replaced the decomposition module with Prophet decomposition (w/Prophet) to evaluate the adaptability of our framework. On the ETTh1 dataset, this substitution leads to a slight performance decline, whereas on the Exchange dataset, we observe a performance gain. These results suggest that while our design is flexible to different decomposition choices, the effectiveness may vary across datasets.

In addition, we conducted a deeper investigation into the influence of sliding window size on the decomposition process. On the ETTh1 dataset, we evaluated the window sizes of 13, 25 (default in StreamTS), 49, and 65. The results are summarized in Table 8. This observation underscores the sensitivity of decomposition effectiveness to the window size. Notably, since ETTh1 is collected hourly from the electricity transformer device, it exhibits a periodicity of 24. Based on the results in Table 8, for the relatively short-horizon forecasting (Pred-96), the window size of 25 achieves the best performance. While for long-horizon forecasting, the most favorable performance arises when the window size (49) is approximately twice the underlying period. One can reasonably expect that choosing a window size aligned with the data cycle or twice its cycle for time series decomposition may further boost the predictive performance of our method. These results indicate that an appropriately chosen window size is crucial for enhancing both decomposition fidelity and predictive accuracy and thus represents a promising avenue for future research.

Table 8.

Ablation study of the window size.

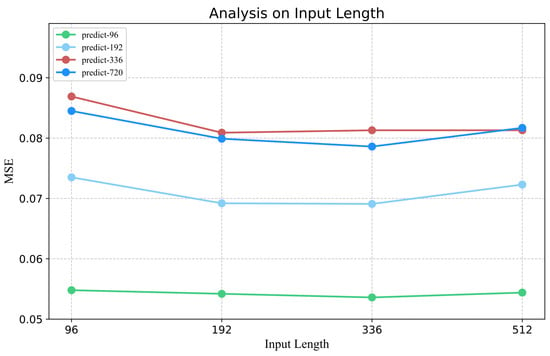

Impact of input length. Figure 11 shows the model performance of predicting the future steps of 96, 192, 336, and 720 on the ETTh1 dataset when the input lengths are 96, 192, 336, and 512, respectively. We can see that the error of the prediction decreases with the input length up to 336, but at that point, the prediction error starts to increase with further increase of the input length. This indicates the input step length in a certain range will bring more auxiliary information to the prediction, but too much data will bring interference to the prediction of the model. Based on these findings, we conclude that excessively long history input lengths do not enhance prediction accuracy and may, in fact, increase computational overhead. Thus, identifying an optimal history length is essential for effective model performance.

Figure 11.

Analysis of input length sensitivity on ETTh1 dataset.

Statistical Analysis. We conducted 10 bootstrap evaluations on the test sets of the ETTh1 and Traffic datasets, each time randomly sampling 90% of the test data, and computed the MSE and MAE for StreamTS, TIME-LLM, and AutoTimes, reporting the results as mean ± standard deviation (Table 9).

Table 9.

Bootstrap evaluation results (mean ± std) of AutoTimes, TIME-LLM, and StreamTS on ETTh1 and Traffic datasets. * denotes that the difference between the corresponding method and StreamTS is statistically significant based on paired t-test (p < 0.05). Bold: best.

The results show that all the three LLM-based methods achieve highly stable predictions with very small standard deviations (typically on the order of ). According to a paired t-test, our proposed StreamTS significantly outperforms the baseline models across all prediction horizons. The statistical analysis highlights the reliability of the experimental conclusion, confirming StreamTS is effective in adapting frozen LLMs for time series forecasting.

5. Conclusions

StreamTS exhibits remarkable potential in adapting frozen LLMs for time series forecasting with minimum training effort. This is achieved via the decomposition of time series data and predicting the short-term season series with a linear model and the long-term trend series with LLMs. Evaluations conducted have demonstrated that the adapted LLMs outperform specialized expert models, thereby affirming their potential as effective tools for time series analysis.

Our framework is designed with strong generalization and adaptability, enabling zero-shot forecasting when combined with traditional approaches such as ARIMA. This makes it particularly suitable for data-scarce or privacy-sensitive domains where large-scale training is infeasible, and its plug-and-play nature further facilitates direct integration into existing workflows. In terms of interpretability, we provide both theoretical proof supporting the decomposition step and empirical visualization of attention distributions across decomposed components, ensuring transparency and user trust. Moreover, by leveraging BC-Prompt and maintaining compatibility with classical statistical tools, our method exhibits robustness under distributional shifts and dynamic environments.

At the same time, we acknowledge remaining challenges in practical deployment, including fairness across heterogeneous datasets, systematic privacy-preserving protocols, and robustness against adversarial inputs. Addressing these issues will be an important direction for future research to further enhance the reliability and responsible use of LLM-based time series forecasting models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F.; methodology, W.S.; software, X.G.; validation, W.Z., Z.L. and Y.C.; formal analysis, M.D.M.; investigation, W.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.F.; writing—review and editing, W.S.; visualization, X.G.; supervision, M.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFC3101601).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gruver, N.; Finzi, M.; Qiu, S.; Wilson, A.G. Large language models are zero-shot time series forecasters. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 36, 19622–19635. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Peng, H.; Fu, J.; Ling, H. Autoformer: Searching transformers for visual recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 12270–12280. [Google Scholar]

- Shumway, R.H.; Stoffer, D.S. ARIMA models. In Time Series Analysis and Its Applications: With R Examples; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 75–163. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.; Chang, W.C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H. Modeling long-and short-term temporal patterns with deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 8–12 July 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An Empirical Evaluation of Generic Convolutional and Recurrent Networks for Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Gwak, D.; Choo, J.; Choi, E. Self-Supervised Contrastive Learning for Long-term Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2024, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.S.; Chen, C.; Cloët, I.C.; Roberts, C.D.; Segovia, J.; Zong, H.S. Contact-interaction Faddeev equation and, inter alia, proton tensor charges. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 92, 114034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Kong, W.; Sen, R.; Zhou, Y. A decoder-only foundation model for time-series forecasting. In Proceedings of the Forty-First International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2024, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Niu, P.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Jin, R. One Fits All: Universal Time Series Analysis by Pretrained LM and Specially Designed Adaptors. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.14782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, G.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Long, M. AutoTimes: Autoregressive Time Series Forecasters via Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.02370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Luong, V.; Mukherjee, L.; Singh, V. SimpleTM: A Simple Baseline for Multivariate Time Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2025, Singapore, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, Z.; Wen, Q.; Sun, L.; Yao, T.; Yin, W.; Jin, R. Film: Frequency improved legendre memory model for long-term time series forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 12677–12690. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Chu, Z.; Zhang, J.Y.; Shi, X.; Chen, P.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y.; Pan, S.; et al. Time-LLM: Time Series Forecasting by Reprogramming Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2024, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- DeepSeek-AI; Guo, D.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, R.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, S.; Wang, P.; et al. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Shen, L.; Zhang, R.; Ding, S.; Wang, B.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y. CrossGNN: Confronting Noisy Multivariate Time Series Via Cross Interaction Refinement. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2023), New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Long, M. iTransformer: Inverted Transformers Are Effective for Time Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2024, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, A.; Li, M.; Smola, A. Automatic Chain of Thought Prompting in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2023, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.; Gulcehre, C.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Empirical Evaluation of Gated Recurrent Neural Networks on Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taud, H.; Mas, J.F. Multilayer perceptron (MLP). In Geomatic Approaches for Modeling Land Change Scenarios; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.; Jenkins, G.M. Some recent advances in forecasting and control. J. R. Stat. Society. Ser. C (Appl. Stat.) 1968, 17, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Lin, X.; Tong, T. Logtrans: Providing efficient local-global fusion with transformer and cnn parallel network for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 24th International Conference on High Performance Computing & Communications; 8th International Conference on Data Science & Systems; 20th International Conference on Smart City; 8th International Conference on Dependability in Sensor, Cloud & Big Data Systems & Application (HPCC/DSS/SmartCity/DependSys), Hainan, China, 18–20 December 2022; pp. 769–776. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, Z.; Wen, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Jin, R. Fedformer: Frequency enhanced decomposed transformer for long-term series forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; pp. 27268–27286. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Y.; Nguyen, N.H.; Sinthong, P.; Kalagnanam, J. A Time Series is Worth 64 Words: Long-term Forecasting with Transformers. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2023, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vazquez, M.J.; Nielen, M.; Gunn, G.J.; Lewis, F.I. Using seasonal-trend decomposition based on loess (STL) to explore temporal patterns of pneumonic lesions in finishing pigs slaughtered in England, 2005–2011. Prev. Vet. Med. 2012, 104, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.J.; Letham, B. Forecasting at scale. Am. Stat. 2018, 72, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreshkin, B.N.; Carpov, D.; Chapados, N.; Bengio, Y. N-BEATS: Neural basis expansion analysis for interpretable time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2020, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 26–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, R.; Yu, H.F.; Dhillon, I.S. Think globally, act locally: A deep neural network approach to high-dimensional time series forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 5634–5643. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, A.; Chen, M.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Q. Are transformers effective for time series forecasting? In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 11121–11128. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Wang, S.; Nie, Y.; Li, D.; Ye, Z.; Wen, Q.; Jin, M. Time-MoE: Billion-Scale Time Series Foundation Models with Mixture of Experts. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR2025, Singapore, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Choromanski, K.; Likhosherstov, V.; Dohan, D.; Song, X.; Gane, A.; Sarlos, T.; Hawkins, P.; Davis, J.; Mohiuddin, A.; Kaiser, L.; et al. Rethinking attention with performers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual Event, Austria, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition Transformers with Auto-Correlation for Long-Term Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2021, Virtual Event, 6–14 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Wu, H.; Liao, X.; Lin, Y.; Chen, J. Empirical mode decomposition in clinical signal analysis: A systematic review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 194, 110566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Langrené, N.; Zhu, S. Unleashing the potential of prompt engineering for large language models. Patterns 2025, 6, 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Choi, Y.; Shieber, S. From explicit cot to implicit cot: Learning to internalize cot step by step. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14838. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Hu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Timesnet: Temporal 2d-variation modeling for general time series analysis. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2022, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Peng, J.; Huang, F.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Xiao, Y. Micn: Multi-scale local and global context modeling for long-term series forecasting. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2022, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Non-stationary transformers: Exploring the stationarity in time series forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 9881–9893. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).