Aging Analysis of HTV Silicone Rubber Under Coupled Corona Discharge, Humidity and Cyclic Thermal Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

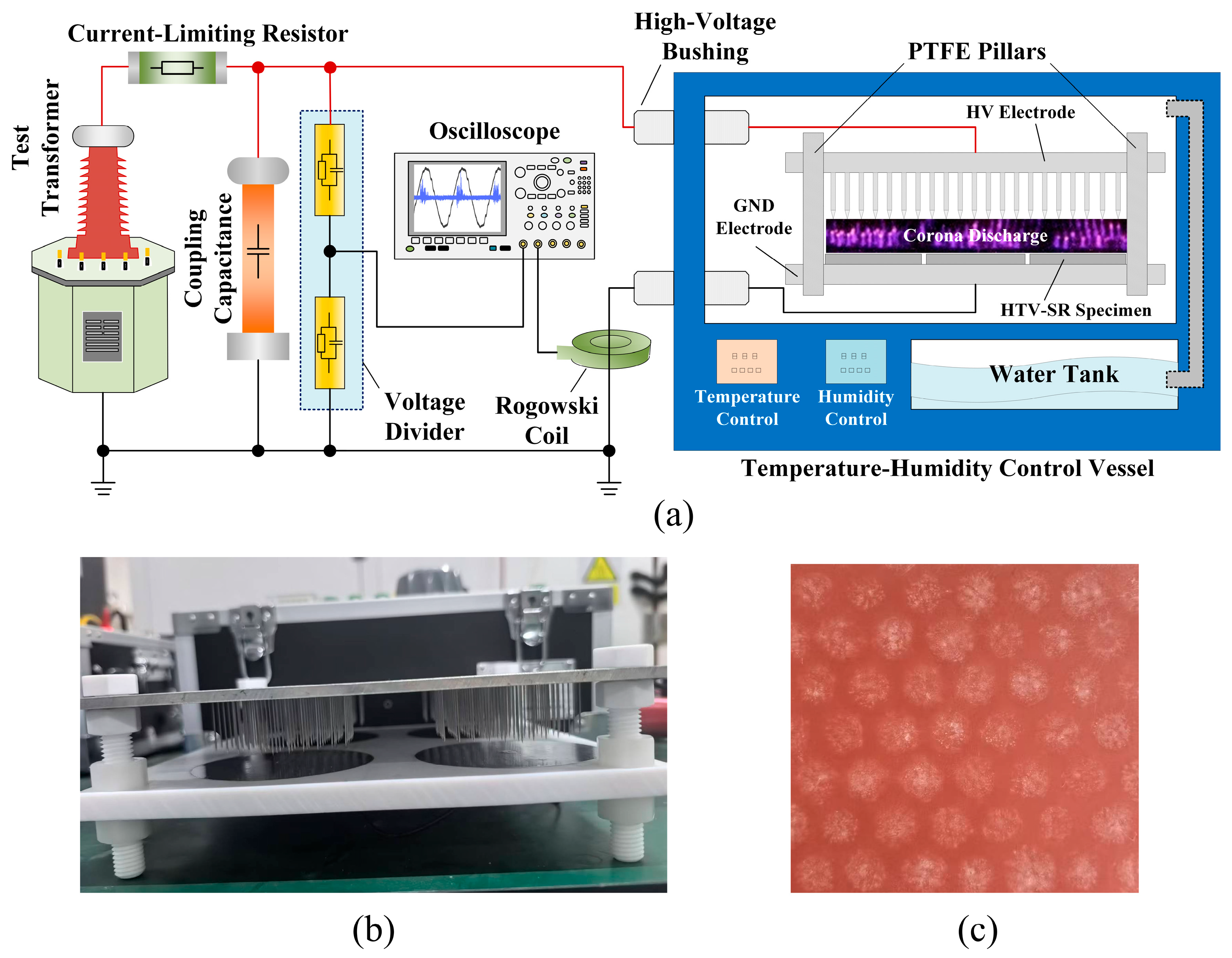

2. Experiments

2.1. Sample Preparation

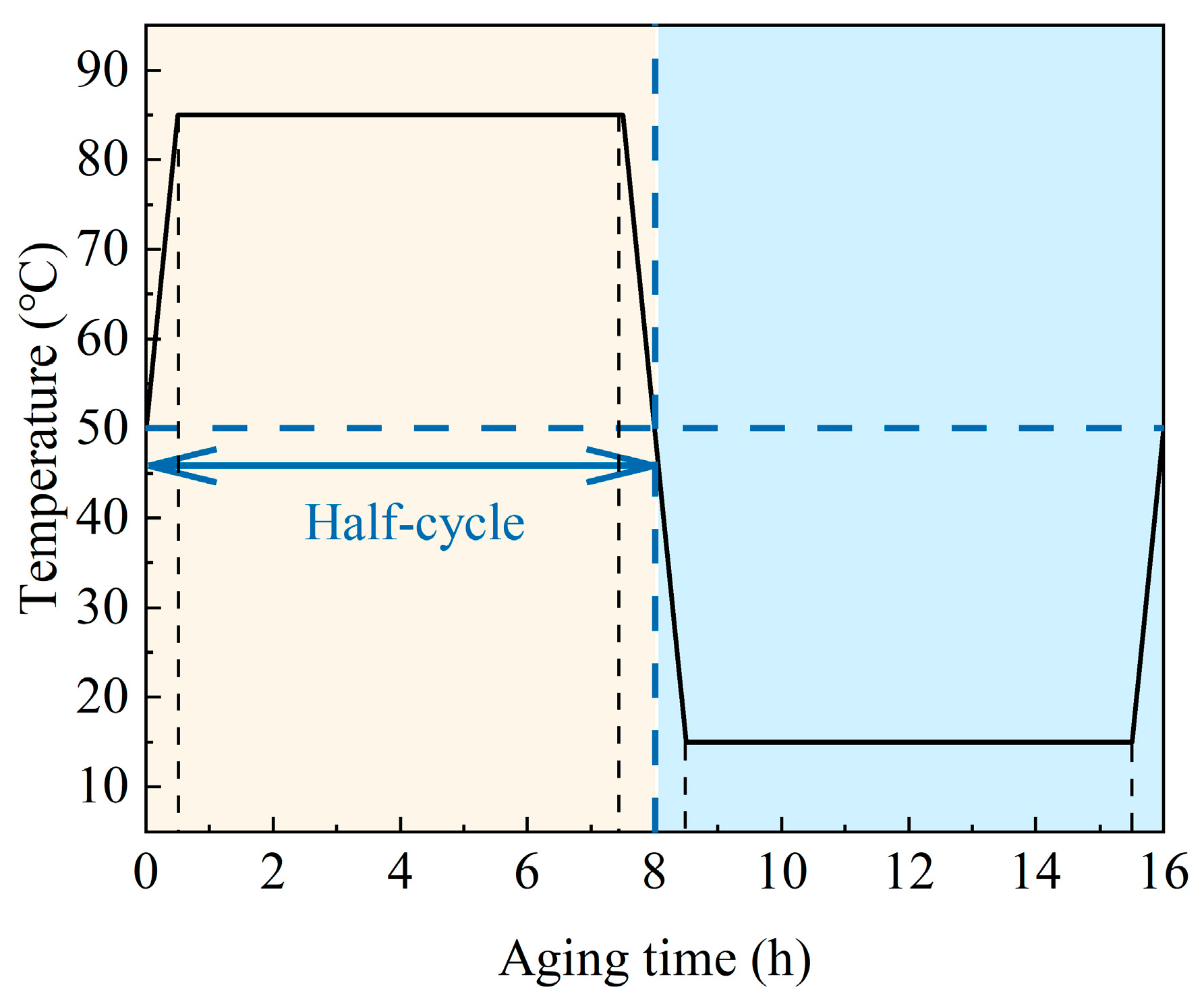

2.2. Accelerated Aging Tests

2.3. Characterization

2.3.1. Surface Morphology, Structural and Mechanical Properties

2.3.2. Electrical Properties

3. Results and Discussion

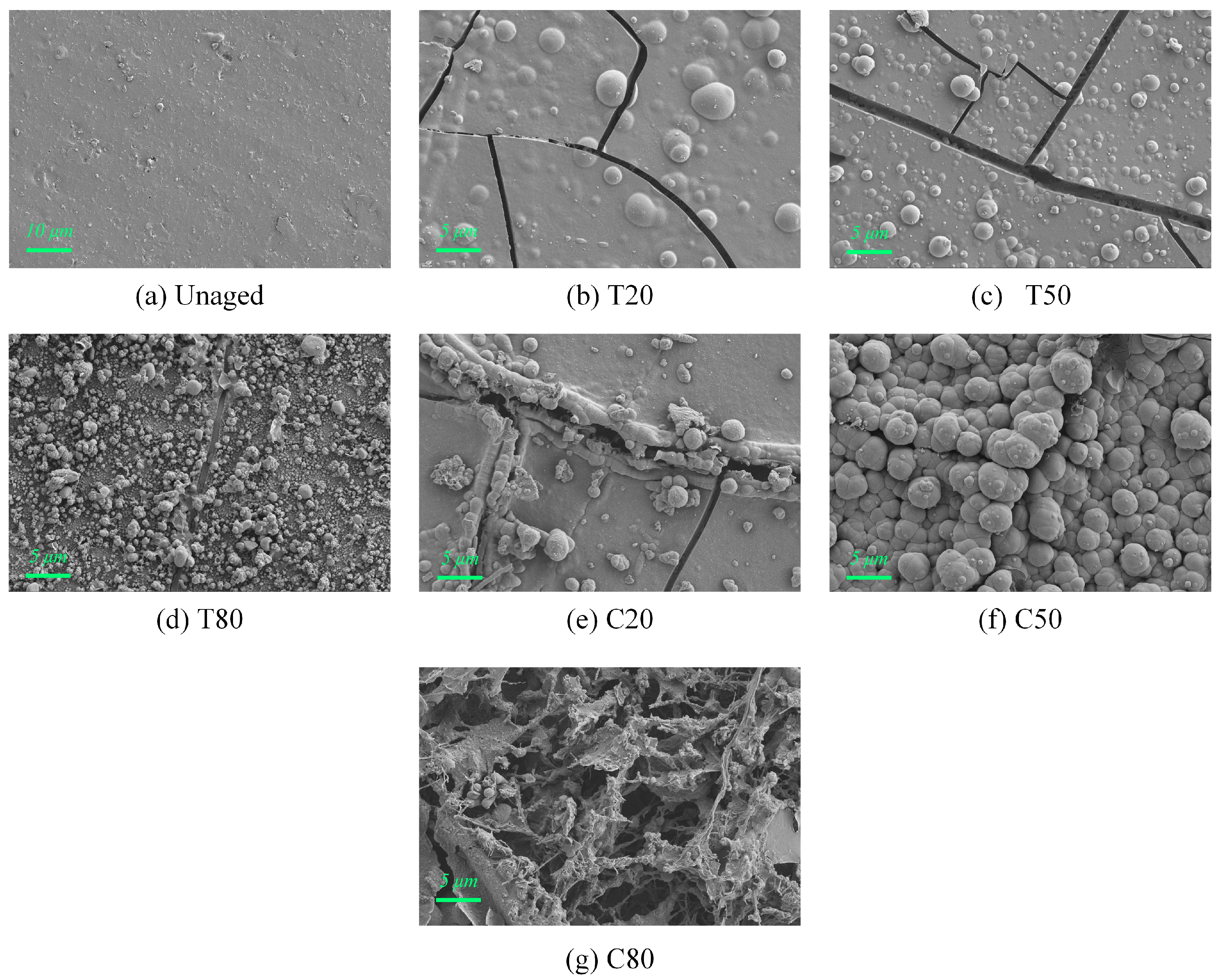

3.1. Surface Morphology

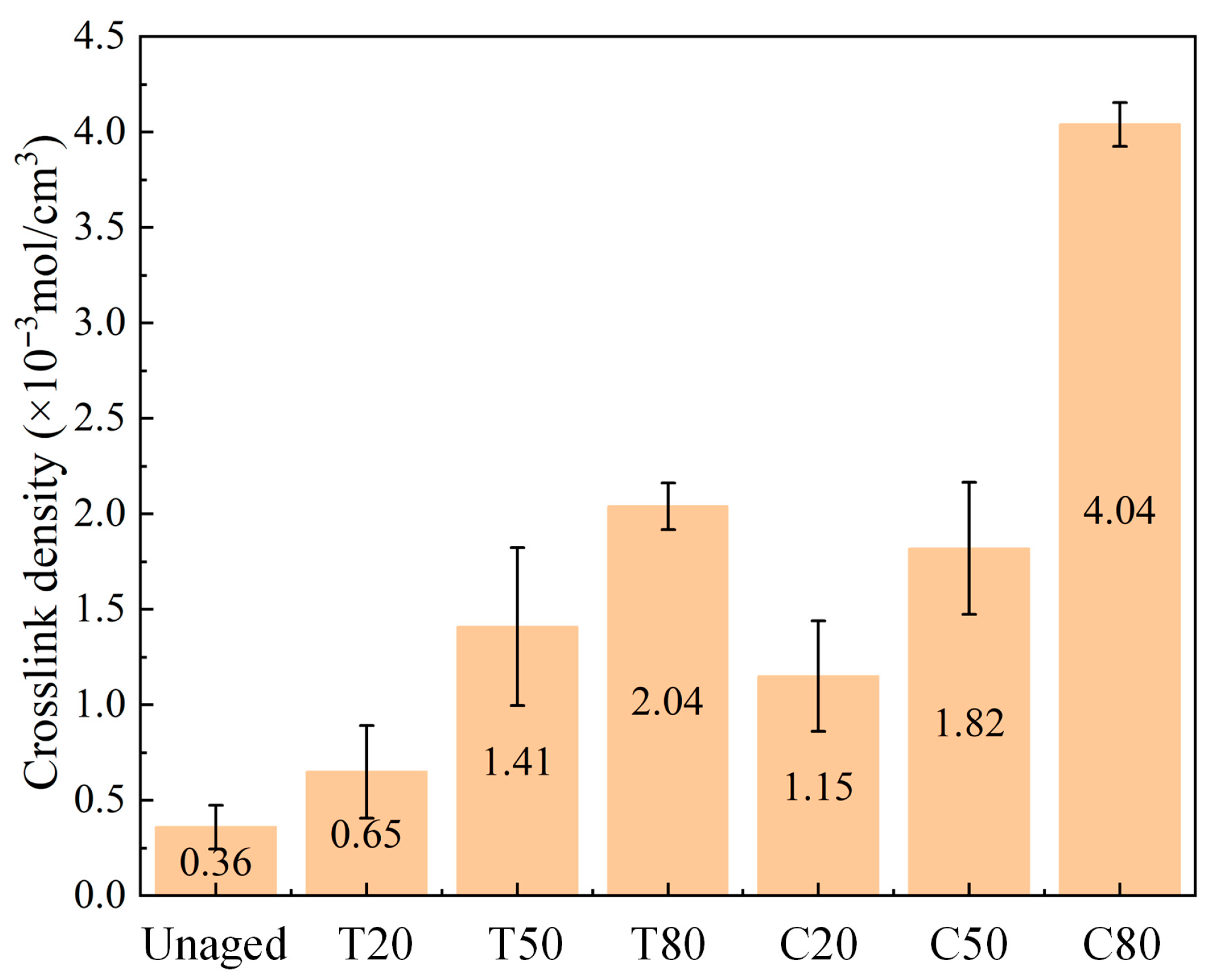

3.2. Structural and Mechanical Properties

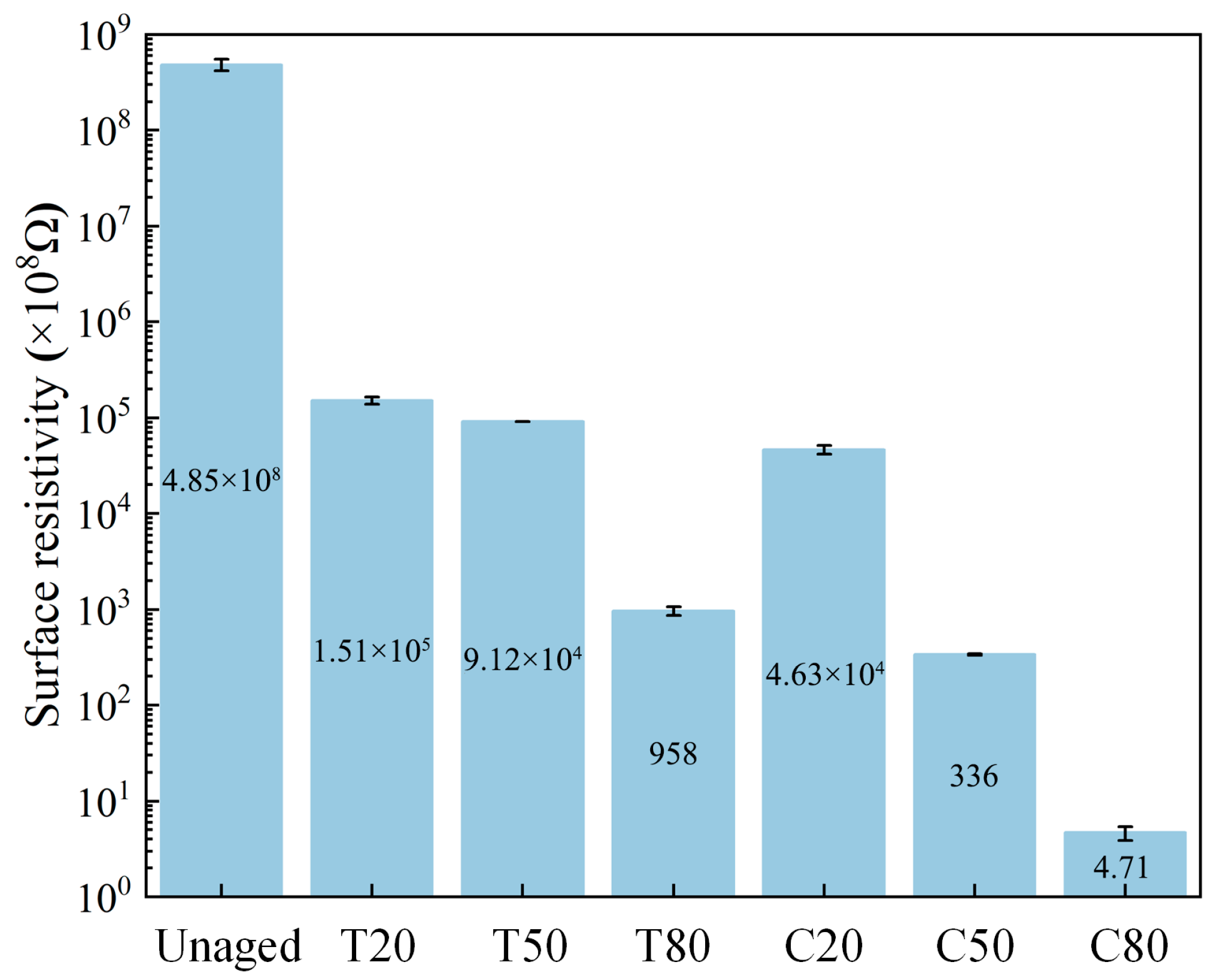

3.3. Electrical Properties

3.4. Discussions

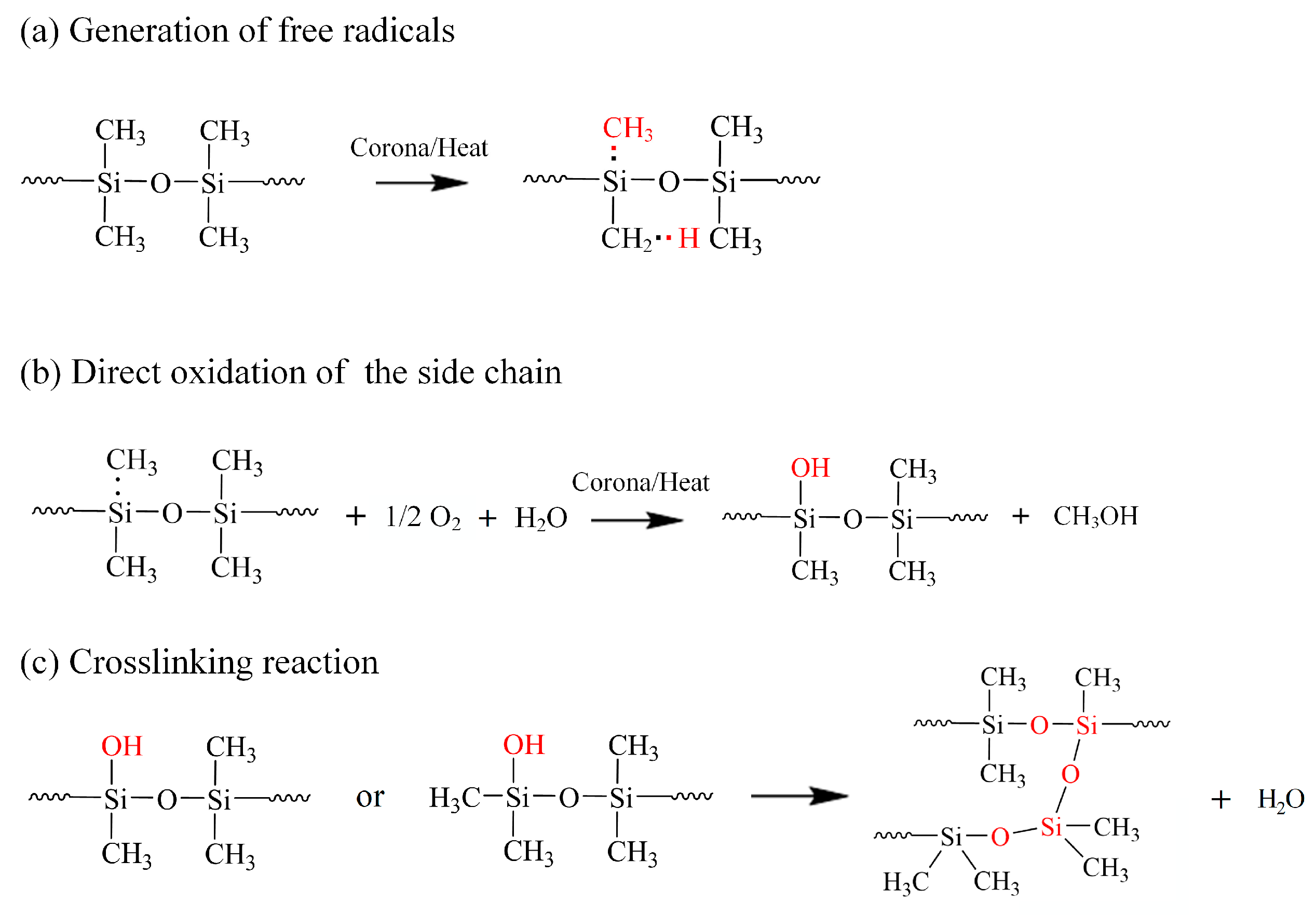

3.4.1. Aging Mechanism of HTV-SR Under Electrical–Thermal–Moisture Stress

3.4.2. Comparative Analysis of Mechanisms Under Constant and Cyclic Temperature Conditions

4. Conclusions

- 1.

- A multi-factor aging platform coupling corona discharge, humidity and constant/cyclic temperature reveals that humidity and thermal conditions markedly influence HTV-SR degradation, with cyclic temperature causing more pronounced aging effects.

- 2.

- Corona discharge induces both chain scission and oxidative crosslinking in HTV-SR, decreasing surface resistivity and flashover strength. Moisture accelerates hydrolysis and interface degradation, leading to increased highly oxidated Si atoms and reduced ductility and insulation stability.

- 3.

- In a multi-factorial aging environment, HTV-SR undergoes severe surface damage, mechanical degradation and insulation failure. Constant temperature aging mainly causes chain scission and powdering, while cyclic temperature promotes crosslinking, increasing brittleness and defects. High humidity further accelerates internal degradation through water condensation and defect synergy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, M.; Xue, J.; Wei, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, G. Review of interface tailoring techniques and applications to improve insulation performance. High Volt. 2022, 7, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, S. Rapid development of silicone rubber composite insulator in China. High Volt. Eng. 2016, 42, 2888–2896. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Jia, Z.; Ye, W.; Guan, Z.; Li, Y. Thermo-oxidative aging analysis of HTV silicone rubber used for outdoor insulation. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2017, 24, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, R.; Shen, W.; Liang, X. Review on aging characterization and evaluation of silicon rubber composite insulator. High Volt. Appar. 2016, 52, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X. Research on property variation of silicone rubber and EPDM rubber under interfacial multi-stresses. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2019, 26, 2027–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.; Phung, B. Accelerated ultraviolet weathering investigation on micro-/nano-SiO2 filled silicone rubber composites. High Volt. 2018, 3, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Song, W.; Wang, G.; Niu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, G. Influence of corona discharge on aging characteristics of HTV silicone rubber material. High Volt. Eng. 2013, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Dong, J.; Wang, Y.; Gond, B. Thermal oxidation ageing effects on silicone rubber sealing performance. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2017, 135, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Ma, J.; Zeng, Y.; Ding, C.; Zhang, C.; Gao, N.; Zhang, J. Study on thermal-cooling aging characteristics of room temperature vulcanized silicone rubber insulation and protection materials. High Volt. Appar. 2020, 56, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, M.; Deng, R.; Jiang, T.; Chen, X.; Pan, A.; Zhu, L. Study on corona aging characteristics of silicone rubber material under different environmental conditions. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2022, 29, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xie, C.; Wang, R.; Gou, B.; Luo, S.; Zhou, J. Effects of electrical-hydrothermal aging degradation on dielectric and trap properties of high temperature vulcanized silicone rubber materials. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 3805–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Peng, B.; Liu, Z.; Du, Y.; Zhou, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; Yu, X.; Zhou, J. Hygrothermal aging performance of high temperature vulcanized silicone rubber and its degradation mechanism. High Volt. 2023, 8, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Fang, J.; Li, Y.; Lun, Y.; Pan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, C.; Fang, P. Effect of surface structure of silicone-SiO2 composite coatings on its condensation and flashover characteristics. J. Wuhan Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 69, 536–544. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, K.; Hatori, K.; Iura, S. The test method to confirm robustness against condensation. In Proceedings of the 21st European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications, Genova, Italy, 2–5 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.; Li, W.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G. Mechanism of accelerated deterioration of high-temperature vulcanized silicone rubber under multi-factor aging tests considering temperature cycling. Polymers 2023, 15, 3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristy, A. Chapter 3 Theory of infrared spectroscopy. In Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 35, pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke, S. Synthesis, Equilibrium Swelling, Kinetics, Permeability and Applications of Environmentally Responsive Gels; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 81–144. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 528-2009; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic-Determination of Tensile Stress-Strain Properties. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Zeng, S.; Li, W.; Zhao, X.; Peng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhang, G. Degradation of HTV silicone rubber in composite insulators under UVB-corona coupling effect in simulated plateau environments. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2025, 238, 111354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Xu, C.; Guan, R.; Wang, X.; Deng, Y. Simulation of the chalking of silicone rubber based on tetramethylammonium-hydroxide-catalyzed scission reaction. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2023, 208, 110251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassé, W.; Lang, M.; Sommer, J.; Saalwächter, K. Crosslink density estimation of PDMS networks with precise consideration of networks defects. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Liang, X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J. Effects of AC and DC corona on the surface properties of silicone rubber: Characterization by contact angle measurements and XPS high resolution scan. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2017, 24, 2911–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Yan, N.P.; Yang, C.J.; Wang, X.L.; Jia, Z.D. Effects of platinum catalyst on the dielectric properties of addition cure silicone rubber/SiO2 nanocomposites. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2021, 28, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Xiang, Y.; Huang, H.; Jiang, X. Characteristics of powdered layer on silicone rubber surface. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancastre, J.; Fernandes, N.; Margaça, F.; Salvado, I.; Ferreira, L.; Falcão, A.; Casimiro, M. Study of PDMS conformation in PDMS-based hybrid materials prepared by gamma irradiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2012, 81, 1336–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallathambi, T.; Ramachandran, V.; Palanivelu, R. Effect of silica nanoparticles and BTCA on physical properties of cotton fabrics. Mater. Res. 2011, 14, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Choi, K.; Jo, W.; Hsu, S. Structure-property relationships of polyimides: A molecular simulation approach. Polymer 1998, 39, 7079–7087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, L.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Ma, Z.; Cai, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, S. Influence mechanisms of ultraviolet irradiation aging on DC surface discharge properties of silicone rubber in dry and humid air. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 678, 161107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, K.; Tang, Z.; Xie, P.; Hu, J.; Fu, Z. Study on silicone rubber composite insulator modified by high-energy electron beam irradiation. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2023, 30, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.; Phung, B.; Hoffman, M. Performance of silicone rubber composites with SiO2 micro/nano-filler under AC corona discharge. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2016, 23, 2804–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Temperature/°C | Average Temperature/°C | Cycle Frequency f/h−1 | Relative Humidity/% | Voltage Value of Needle Tip/kV | Field Strength Near the Surface/(kV·cm−1) | Time/h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T20 | 50 | 50 | \ | 20 | 11.5 r.m.s. | 15.0 | 240 |

| T50 | 50 | ||||||

| T80 | 80 | ||||||

| C20 | 15~85 | 1/16 | 20 | ||||

| C50 | 50 | ||||||

| C80 | 80 |

| Group | Si(–O)2 | Si(–O)3 | Si(–O)4 | Highly Oxidated Si Atoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaged | 64.9% | 28.6% | 6.5% | 35.1% |

| T20 | 46.5% | 41.0% | 12.5% | 53.5% |

| T50 | 37.3% | 34.3% | 28.4% | 62.7% |

| T80 | 27.3% | 46.3% | 26.4% | 72.7% |

| C20 | 40.7% | 33.7% | 25.6% | 59.3% |

| C50 | 32.4% | 26.1% | 41.5% | 67.6% |

| C80 | 30.3% | 24.4% | 45.3% | 69.7% |

| Sample | Unaged | T20 | T50 | T80 | C20 | C50 | C80 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | 9.32 | 7.75 | 7.36 | 6.20 | 7.60 | 7.05 | 5.65 |

| β | 7.16 | 19.61 | 8.83 | 20.25 | 14.34 | 6.71 | 26.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, M.; Zeng, S.; Gao, C.; Liu, Y.; Yan, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, G. Aging Analysis of HTV Silicone Rubber Under Coupled Corona Discharge, Humidity and Cyclic Thermal Conditions. Electronics 2025, 14, 4071. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204071

Lu M, Zeng S, Gao C, Liu Y, Yan X, Liu Z, Zhang G. Aging Analysis of HTV Silicone Rubber Under Coupled Corona Discharge, Humidity and Cyclic Thermal Conditions. Electronics. 2025; 14(20):4071. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204071

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Ming, Shiyin Zeng, Chao Gao, Yuelin Liu, Xinyi Yan, Zehui Liu, and Guanjun Zhang. 2025. "Aging Analysis of HTV Silicone Rubber Under Coupled Corona Discharge, Humidity and Cyclic Thermal Conditions" Electronics 14, no. 20: 4071. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204071

APA StyleLu, M., Zeng, S., Gao, C., Liu, Y., Yan, X., Liu, Z., & Zhang, G. (2025). Aging Analysis of HTV Silicone Rubber Under Coupled Corona Discharge, Humidity and Cyclic Thermal Conditions. Electronics, 14(20), 4071. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204071