Abstract

Sensitive scalp (SSC) is a common but often overlooked dermatological state, characterized by subjective symptoms such as pruritus, tingling, tightness, pain, or burning sensations. Primary SSC typically occurs in the absence of visible clinical inflammation. Numerous studies have suggested that the onset of SSC may be influenced by a variety of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including physical (ultraviolet radiation, changes in temperature and humidity), chemical (cosmetic ingredients, environmental pollutants), and psychological factors (emotional stress). This article provides a narrative review of the current research on SSC, drawing on literature published between 1963 and 2024 in PubMed, Elsevier, and Web of Science databases. We summarize its hallmark symptoms, available evaluation methods, potential mechanisms, and contributing factors and propose corresponding scalp care recommendations. This review aims to offer theoretical insights into the pathogenesis of SSC and to support the development of effective protective strategies.

1. Introduction

The International Forum for the Study of Itch (IFSI) defines sensitive skin as a syndrome characterized by the occurrence of unpleasant sensations such as stinging, burning, pain, pruritus, and tingling in response to stimuli that should not normally provoke such feelings. These sensations cannot be explained by visible skin lesions attributable to any dermatological disease. The skin may appear normal or present with erythema. Sensitive skin can affect all parts of the body, particularly the face [1]. However, it is not restricted to the face and frequently occurs on other regions such as the hands, scalp, feet, neck, trunk, and back [2]. Due to its thin skin and rich network of sebaceous glands, nerves, and blood vessels, the scalp is particularly prone to sensitivity.

Sensitive scalp (SSC) is defined as the occurrence of abnormal and unpleasant sensory reactions such as pruritus, stinging, tightness, pain, and burning in response to environmental stimuli in the absence of obvious clinical signs of inflammation [3]. While these symptoms are commonly seen in various scalp conditions, it is noteworthy that patients may experience these sensations even without a clear underlying skin disease. In a French epidemiological study on SSC [4], 11.5% of individuals with SSC reported coexisting scalp disorders, such as seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, or alopecia, while 88.5% did not present with any known scalp diseases. Although the prevalence of scalp disorders was higher among those with SSC compared to non-sensitive individuals (11.5% vs. 1.1%), these disorders are not considered direct symptoms of scalp sensitivity. An increased degree of scalp sensitivity was associated with a higher likelihood of concurrent scalp diseases. However, the majority of individuals, particularly those with mild to moderate sensitivity, did not exhibit any identifiable dermatological diseases.

In addition, some researchers have classified sensitive scalp into two types: primary sensitive scalp and secondary sensitive scalp [5]. Primary sensitive scalp refers to sensitive symptoms occurring in the absence of known scalp diseases, while secondary sensitive scalp refers to sensitive scalp symptoms associated with existing skin conditions such as seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, or hair loss. Although these two types of sensitive scalp share common symptoms, they differ in their etiology and treatment strategies. This review will focus on primary sensitive scalp, in which no dermatologic disease is present, although reference to secondary causes will be made when relevant for context. We will explore the symptoms, current assessment methods, potential pathogenic mechanisms, epidemiological characteristics, and triggering factors of SSC. Through the analysis of existing literature, we will propose management strategies. Furthermore, we will also highlight emerging insights from the fields of lipidomics and microbiomics, aiming to deepen understanding in this area and provide guidance for future research.

2. Symptoms and Evaluation of Sensitive Scalp

The primary symptoms of scalp sensitivity are similar to those observed in sensitive skin on other body sites and commonly include pruritus, stinging, tightness, pain, and burning sensations [2]. Among these, pruritus is the most frequently reported complaint in individuals with SSC. Scalp pruritus may result from various causes. It is now classified into the following categories based on the underlying etiologies [6,7]: dermatological (e.g., seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis [8,9,10]); neuropathic (diabetic neuropathy [11], postherpetic neuralgia [12], or small fiber neuropathy [13]); systemic (e.g., chronic kidney disease, liver disorders, and hematological malignancies [6]); and psychogenic (e.g., anxiety, delusional parasitosis [14,15]). When no identifiable underlying disease is found, the condition is categorized as pruritus of unknown origin.

SSC is characterized by abnormal or unpleasant sensory reactions. In the absence of identifiable dermatological conditions or specific pathological mechanisms, the associated pruritus is classified as pruritus of unknown origin [1,4]. Individuals with SSC often exhibit a reduced threshold for external stimuli and are more susceptible to environmental triggers such as temperature fluctuations, pollutants, and hair care products [6]. Tingling sensations are believed to result from overstimulation of cutaneous sensory nerve endings, potentially due to underlying neurological conditions or nerve damage [16]. The SSC reacts easily to even minor stimuli, often leading to burning, stinging, or pain. Exposure to irritant chemicals such as shampoos, conditioners, and hair dyes may provoke burning sensations on the scalp. Additionally, a feeling of scalp tightness may be caused by excessive lipid removal and subsequent dryness due to the prolonged use of overly harsh cleansing shampoos [17].

Topical tests such as the capsaicin and lactic acid sting tests are commonly used to evaluate facial sensitive skin. However, due to the presence of hair, these methods are not easily applicable to the scalp [18]. Currently, the evaluation of scalp sensitivity primarily relies on the assessment of subjective symptoms, which remains the main approach for identifying SSC and determining its severity.

Three commonly used subjective evaluation methods for SSC include the four-grade self-assessment scale, the 3S questionnaire, and the 10Q questionnaire. The four-grade self-assessment method classifies sensitivity into four levels (non-sensitive, mildly sensitive, sensitive, and very sensitive) based on the subject’s perception. Although it allows for rapid initial screening, the results are often influenced by the individual’s understanding of what constitutes a “SSC”, thereby limiting objectivity. The 3S questionnaire assesses five key symptoms-pruritus, stinging, tightness, pain, and burning, and evaluates their impact on quality of life using a 0–4 scale. A total score ranging from 0 to 20 is calculated and used to classify the severity: mild (≤8), moderate (9–11), and severe (≥12). This method focuses on quantifying the subjective severity of symptoms and their interference with daily life, offering advantages in standardized scoring and diagnostic stratification [4].

The 10Q questionnaire explores the association between 10 common environmental triggers (e.g., sunlight, heat, dryness, stress) and symptom occurrence [18]. It emphasizes identifying the relationship between specific triggers and symptoms through a trigger exposure frequency score (maximum 50 points), thus highlighting the influence of environmental factors on scalp sensitivity.

A 2016 epidemiological study conducted in China compared the application of these three methods [18]. The 3S questionnaire revealed an age-dependent increase in the prevalence of SSC. Yet, the self-assessment scale seemed to underestimate prevalence in older adults, likely due to differences in self-awareness. Strong correlations were observed between the 3S and 10Q scores, and both identified pruritus as the predominant symptom. However, discrepancies emerged in the evaluation of stinging, tightness, and burning sensations, reflecting the differing emphases of each method.

Overall, current evaluations of SSC remain predominantly subjective. Although advances have been made in symptom stratification and trigger identification, assessment remains constrained by the limitations of self-reporting. These include difficulties in accurately recalling symptom frequency and intensity due to the transient and subjective nature of symptoms. Additionally, cultural differences may influence symptom interpretation and reporting. For instance, emotional stress was reported as a key trigger by 53.03% of participants in a French study [19], compared to only 15.2% in a Korean cohort [20]. These findings highlight the influence of recall bias, cultural variability, and the lack of objective biomarkers in the assessment of SSC.

3. Barrier Function of Sensitive Scalp

As a distinct cutaneous region, the scalp represents one of the body sites with the highest density of hair follicles [21]. Within the dermis, deeply rooted follicles in close association with large sebaceous glands form a symbiotic unit that creates a low-oxygen, high-humidity microenvironment. In parallel, the rich capillary network and the dense distribution of sensory nerve endings constitute a highly sensitive surveillance system [6,22], rendering the scalp particularly responsive to both exogenous and endogenous stimuli. Currently, due to the limited direct research on primary sensitive scalp, much of the discussion is based on extrapolations from studies on other skin conditions. Based on previous studies, such stimuli can activate transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channels. This leads to the release of substance P and multiple neuropeptides, triggering neurogenic inflammation and eliciting symptoms of sensitive skin [23,24,25]. Given that SSC is a form of sensitive skin, similar mechanisms may also be involved in the development of SSC. Furthermore, disruption of the scalp barrier may also play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of SSC.

Multiple inflammatory skin diseases have been shown to be closely associated with barrier dysfunction. For instance, in atopic dermatitis (AD), disruption of the stratum corneum structure and intercellular lipid lamellae compromises the permeability barrier [26,27], facilitates penetration of environmental factors, and perpetuates a vicious cycle under the drive of type 2 inflammatory responses [28]. Concurrently, microbial diversity on AD skin is markedly reduced. Pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus colonize abnormally, while commensals decline. This dysbiosis further weakens barrier function and amplifies inflammation [29,30,31]. Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is characterized by barrier dysfunction in sebum-rich areas [32,33], primarily driven by aberrant interactions between sebum and microbes. Specifically, Malassezia secretes lipases that hydrolyze triglycerides, generating metabolites like oleic acid and arachidonic acid. These metabolites disrupt keratinocyte differentiation and barrier integrity, and simultaneously induce inflammatory responses [34,35,36]. Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of the interplay between sebum, lipid metabolism, and the microbiome in maintaining skin barrier homeostasis. Their imbalance often leads to barrier disruption and exacerbated inflammation.

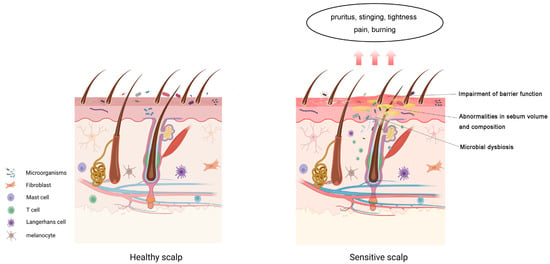

As one of the areas with the highest sebaceous secretion and follicular density, the scalp barrier is particularly vulnerable to changes in sebum production and the microbiome [37]. Although most of the current evidence on SSC comes from epidemiological studies, existing findings clearly show that SSC is closely associated with scalp barrier dysfunction. Ma et al. (2019) found that SSC is frequently accompanied by increased pH, higher sebum secretion, and microbial dysbiosis, particularly an increase in Propionibacterium and a decrease in microbial diversity [21]. These results strongly suggest that the balance between sebum, lipid metabolism, and the microbiome plays a critical role in maintaining scalp barrier function, and its disruption may be a key factor in the development of SSC symptoms (Figure 1). However, the exact roles of lipid composition and microbial changes in SSC are still not fully understood. Given the close, dynamic interplay between the lipidome and microbiome, combining lipidomics and microbiomics could offer new insights into the mechanisms underlying scalp barrier dysfunction in SSC. Future research could focus on several key areas, including identifying the specific lipidomic profile associated with SSC, examining microbial changes during SSC development, and understanding how these lipid and microbial alterations impair the scalp barrier and promote inflammation at the molecular level. These studies are essential for further elucidating the complex pathophysiology of SSC and could provide a theoretical basis for developing targeted treatments and scalp care products.

Figure 1.

Components of the sensitive scalp barrier. Sensitive scalp condition may involve impaired barrier function, altered Skin surface lipids (SSL) composition, and microbial dysbiosis. The main symptoms include pruritus, tingling, tightness, pain, and burning sensations.

4. Epidemiology and Triggers of Sensitive Scalp

Epidemiological studies on SSC indicate that the prevalence generally ranges from 30% to 56%. Most of these studies rely on self-report questionnaires, which are inherently subjective. Differences in regional lifestyle habits, cultural backgrounds, and environmental factors can introduce response bias, potentially affecting the reported prevalence rates. Furthermore, variations in sample size and questionnaire design may contribute to biases in the results. For instance, four-level self-assessment questionnaires tend to overestimate the prevalence, while structured tools, such as the 3S questionnaire, tend to provide more conservative estimates [18]. Although the prevalence estimates vary across studies, the general trends in identifying the factors influencing SSC appear to be consistent.

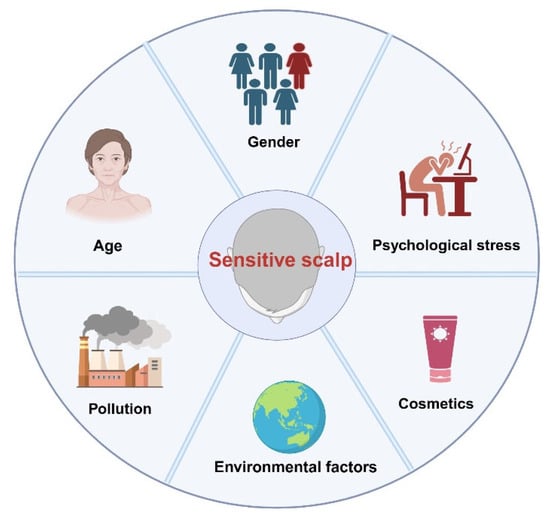

4.1. Prevalence of Sensitive Scalp by Age and Gender

Further analysis of the epidemiological survey results revealed that the prevalence of SSC varies by age and gender. Several studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of SSC is significantly higher in women than in men. A nationwide survey conducted in France [19] revealed that 47.4% of women reported having SSC, compared to only 40.8% of men (p < 0.05). Subsequent research further confirmed this finding [4], showing that the proportion of SSC in women was 35.56%, which was significantly higher than the 29.10% observed in men. In addition, a cohort study focusing on individuals with hair loss [38] showed that 84.31% of patients with SSC were women, while only 15.69% were men. The higher prevalence in females may be attributed to differences in neural sensitivity, hormonal fluctuations, and more frequent use of cosmetic products. Additionally, elevated anxiety levels in women may enhance pain perception [39].

A significant association also appears to exist between age and the prevalence of SSC. Misery et al. [4] (2011) reported that the prevalence of SSC in the French population increased with age, rising from 23.16% in individuals aged 15–17 years to 39.07% in those aged ≥75 years. This trend was hypothesized to be associated with a reduction in epidermal nerve endings [40] and long-term use of irritating shampoos. Similarly, Ma et al. [18] (2016) observed that in Chinese women, the self-assessed prevalence of SSC peaked at 54.54% in the 30–39 age group, while assessments based on the 3S questionnaire indicated a continuous age-related increase, reaching 57.23% in the 50–60 age group. Burroni et al. (2022) [38] further confirmed that among patients with hair loss, the prevalence of sensitive scalp was highest (49.02%) in individuals over the age of 50. This phenomenon was attributed to the loss of nerve endings [40] and the imbalance of scalp microbiota in the elderly [38]. Collectively, these findings suggest that advancing age may increase the risk of SSC through a combination of neurodegeneration and chronic exposure to irritants. Additionally, in the elderly, sebaceous glands may become enlarged. However, sebum secretion levels tend to decline with age [41,42]. Studies have also shown that the content of stratum corneum lipids decreases in aged skin, particularly ceramides [43], leading to a weakened barrier function. Although TEWL does not increase significantly in aged skin [44,45], the decline in hydration capacity makes it more prone to dryness. Meanwhile, cumulative photoaging damage may impair barrier repair capacity [46], further increasing scalp sensitivity to exogenous stimuli and thereby elevating the risk of developing SSC.

4.2. Psychological Stress and Sensitive Scalp

Psychological stress can also exacerbate symptoms of SSC [47]. A French study reported that 53.03% of patients identified emotional fluctuations as a trigger for their symptoms [19], while a study conducted in China found a significant association between stress and scalp tightness (OR = 3.201, p < 0.001) [18]. Conditions such as anxiety, depression, stress, and emotional dysregulation have been shown to aggravate symptoms of skin sensitivity. This has been confirmed by multiple psychological assessments conducted among patients with sensitive skin [48,49,50,51]. Chronic anxiety may activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and increase the secretion of stress hormones, which impairs stratum corneum hydration, elevates TEWL, and alters the composition of epidermal lipids and structural proteins-ultimately leading to scalp barrier dysfunction [52,53]. In addition, psychological factors may contribute to the onset of trichodynia. About 35.7% of patients with alopecia experience trichodynia as a consequence of anxiety or depression [54]. It should be emphasized that trichodynia is not a component of SSC, but rather an independent syndrome with overlapping symptoms. The two conditions may coexist clinically [5,55].

4.3. Cosmetic Products and Sensitive Scalp

The use of cosmetic products is one of the major triggers of SSC. A study by Brenaut et al. [56] involving 133 women without scalp diseases found that 53.6% of those with SSC used hair conditioners, compared to 40% in the control group. Moreover, the amount of conditioner used was significantly higher in the SSC group than in controls (5.48 ± 5.87 g/application vs. 2.88 ± 3.75 g/application, p = 0.03). In addition, Misery et al. [19] observed that subjects with sensitive or very sensitive scalps were more frequently irritated by shampoo compared to those with slightly sensitive or non-sensitive scalps. The use of hair dyes can also induce scalp issues such as erythema, pruritus, desquamation, allergic reactions, and stinging sensations. In severe cases, it may even lead to scalp disorders like contact dermatitis [57,58,59]. Further studies have shown that common ingredients in hair conditioners, such as preservatives (e.g., isothiazolinones), fragrances, and cationic polymers, may induce contact dermatitis, pruritus, and inflammatory responses by forming residues on the scalp and altering barrier function and the local microenvironment [60,61,62]. In fact, epidemiological and toxicological evidence has shown that certain sensitizing components in scalp cosmetics-such as surfactants, para-phenylenediamine (PPD), fragrance mixtures, and isothiazolinone preservatives (methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone) can damage the scalp barrier, facilitate allergen penetration, and potentially activate delayed-type hypersensitivity responses [62,63]. Extremes in cleansing habits also negatively affect scalp barrier function. Excessive cleansing can increase TEWL and impair barrier integrity, raising exposure to irritants and triggering scalp sensitivity [19]. Conversely, infrequent cleansing can lead to sebum buildup, increasing the occurrence of flaking, pruritus, and dryness [64]. A study by Kato et al. [65] demonstrated that scalp itchiness and greasiness increased at 72 h after shampooing, but these symptoms can be rapidly relieved by re-washing the scalp.

4.4. Environmental Factors: Physical and Chemical Triggers

Environmental factors are major exogenous triggers of SSC. A study conducted in China [18] revealed that 59.06% of patients identified high temperatures as a primary trigger, while 51.52% reported sensitivity to solar ultraviolet radiation. Notably, sun exposure was significantly associated with burning sensations in individuals with SSC. Both dry air and hot, humid conditions can exacerbate TEWL from the stratum corneum, thereby intensifying pruritus symptoms. Although epidemiological data support the association between these environmental factors and SSC, the underlying mechanisms remain hypothetical and currently lack direct experimental validation. The following are some hypothetical mechanisms proposed based on existing literature, aimed at explaining how environmental factors may potentially exacerbate the symptoms of SSC.

Elevated temperatures markedly enhance sebaceous gland activity. For each 1 °C increase in temperature, the rate of sebum secretion rises by approximately 10% [66]. Excessive sebum production can promote the growth of anaerobic and lipophilic microorganisms. When excessive sebum blocks hair follicles and creates hypoxic conditions, Cutibacterium acnes can overproliferate and release more free fatty acids, potentially triggering inflammatory responses in the scalp [67]. Furthermore, high temperatures and high humidity also facilitate the proliferation of Malassezia species. These yeasts metabolize saturated fatty acids into unsaturated fatty acids such as oleic acid and arachidonic acid. The excessive accumulation of these metabolites can penetrate the compromised barrier, stimulate nerve endings, and induce inflammatory responses [68,69]. Overall, high temperatures promote sebum secretion and alter the skin’s microecological environment. This leads to the accumulation of lipid metabolic products, such as free fatty acids and unsaturated fatty acids, which can stimulate nerve endings and trigger inflammatory responses, exacerbating sensitive scalp symptoms.

Environmental pollutants can affect sebum components on the scalp. Squalene, an important component of sebum, is susceptible to oxidative degradation by environmental pollutants such as ozone, UVA radiation, and cigarette smoke [70,71]. Studies have shown that squalene degradation products, particularly squalene monohydroperoxide (SQOOH), can stimulate keratinocyte proliferation and inflammatory responses [66]. Air pollutants are a complex mixture of airborne particles of varying sizes and chemical compositions, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter (PM), ozone, and cigarette smoke [72]. Exposure to air pollutants can induce oxidative stress in the skin, subsequently disrupting the integrity of the skin barrier by altering TEWL, inflammatory signaling pathways, stratum corneum pH, and the skin microbiome. Prolonged contact of PM with the scalp may contribute to scalp inflammation, pruritus and dryness-symptoms that closely resemble those observed in sensitive scalp conditions [47,73].

Overall, although the relationship between these environmental factors and SSC symptoms is supported by epidemiological studies, the understanding of the underlying mechanisms remains largely hypothetical, with insufficient experimental validation. We hypothesize that environmental factors may exacerbate sensitive scalp symptoms through multiple pathways, including influencing sebum secretion, altering the microbiota, disrupting the skin barrier, and inducing oxidative stress. Future experimental research is expected to further validate these hypotheses and provide a more solid theoretical foundation for the prevention and treatment of sensitive scalp.

Figure 2.

Factors Affecting Sensitive Scalp.

Table 1.

Epidemiological Factors Affecting Sensitive Scalp: A Summary of Data and Conclusions.

5. Management of Sensitive Scalp

The symptoms of SSC are influenced by a variety of endogenous and exogenous factors. As a suboptimal health condition, SSC is often overlooked. However, individuals with scalp sensitivity are more prone to disorders such as alopecia and dermatitis. Therefore, it is essential to establish long-term awareness of protection and care for SSC. Based on current evidence, this article proposes a systematic management approach:

5.1. Cosmetic Use and Cleansing

Cosmetic use and cleansing practices represent major triggers of SSC. Daily care should prioritize mild cleansing products, with amphoteric surfactants or gentle anionic surfactants being preferred [74,75]. In addition, studies have shown that shampoos containing Hamamelis virginiana extract can help alleviate symptoms of sensitive scalp [76]. Maintaining an appropriate hair-washing frequency (once every 1–2 days) helps sustain scalp homeostasis [64]. When using conditioners or similar products containing cationic surfactants, direct contact with the scalp should be avoided and thorough rinsing ensured to minimize residual effects on the barrier [56,77]. Furthermore, the frequency of hair coloring and perming should be reduced to avoid chemical-induced sensitivity [63]. The use of high-temperature styling tools such as flat irons should also be limited, as they may burn the scalp and compromise barrier integrity [78].

5.2. Photoprotection and Environmental Care

Ultraviolet exposure can aggravate symptoms in SSC patients, making photoprotection indispensable. Wearing a sun hat can prevent excessive sun exposure that leads to barrier damage and scalp burning sensations [18,79]. Scalp care should also be adapted to seasonal conditions. In hot and humid environments, products containing sebum-controlling and antimicrobial ingredients may help suppress excessive sebum secretion and the proliferation of Malassezia [80]. In cold or dry seasons, hydration should be reinforced with products containing glycerol, hyaluronic acid, or ceramides to improve stratum corneum hydration [81].

5.3. Psychological Management and Lifestyle

Psychological stress is closely associated with the onset and exacerbation of SSC, while emotional disturbances frequently aggravate symptoms such as scalp tightness and trichodynia. Accordingly, daily management should emphasize the identification and control of stressors [82], as well as maintaining regular sleep–wake cycles and sufficient sleep [83,84], in order to preserve neuroendocrine balance and the stability of the scalp barrier.

5.4. Medical Intervention

If patients present with persistent erythema, scaling, or similar symptoms, they should seek medical attention promptly. When necessary, dermoscopy and other diagnostic tests can help exclude underlying inflammatory or allergic dermatoses, followed by systemic or targeted therapies under medical supervision. Sensitive scalp syndrome primarily refers to primary sensitive scalp symptoms, which occur without any identifiable underlying dermatological conditions. For patients exhibiting noticeable erythema, scaling, or similar clinical signs, secondary sensitive scalp should be considered, which may be associated with scalp disorders such as seborrheic dermatitis.

6. Conclusions

SSC has gained increasing attention in dermatology. The most common symptoms include subjective discomfort such as itching, tingling, or burning sensations, and primary SSC is characterized by the absence of visible scalp lesions. Current assessment methods mainly rely on self-reported questionnaires. Although such tools are useful for preliminary classification, they are highly susceptible to bias. This underscores the urgent need for objective and standardized diagnostic criteria.

At present, most mechanistic insights into SSC are extrapolated from studies on other skin sites and have not been fully validated on the scalp. Despite the incomplete understanding of SSC pathogenesis and the lack of well-established experimental models, existing evidence suggests that alterations in lipid metabolism and imbalances in the scalp microbiota may play crucial roles in its development.

Applications of lipidomics and microbiomics in SSC research remain at an early stage, but these approaches have been widely applied in the study of other skin diseases, such as seborrheic dermatitis and atopic dermatitis, yielding preliminary results [85,86,87,88]. These studies provide valuable insights and directions for research on SSC. Our research group has previously established a comprehensive multi-omics research platform and demonstrated that factors such as gender, anatomical site, and circadian rhythm significantly influence the composition of skin lipids and microbial communities [89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107]. We believe that these omics-based approaches can offer new perspectives for elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying SSC. Future studies should focus on characterizing the lipidomic profiles associated with SSC, examining dynamic changes in the scalp microbiota during disease progression, and exploring how alterations in lipids and microbes may modulate scalp barrier function and trigger inflammatory responses through molecular mechanisms. Such advancements will ultimately contribute to precision scalp care and evidence-based management, thereby improving clinical outcomes and quality of life for individuals with sensitive scalp.

Author Contributions

X.Y.: Responsible for manuscript writing, editing, and revision; Q.J.: Conducted the literature review, prepared the figures, and participated in manuscript revision; C.H. and Y.J.: Contributed to the overall framework of this paper and provided important suggestions regarding sensitive scalp–related factors and symptoms; H.H. and C.Z.: Provided academic guidance, supervised the research process, and contributed through critical review and revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the project “BTBU Digital Business Platform Project by BMEC”, funded by the Beijing Municipal Education Commission under the program for the classified development of municipal universities.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

References

- Misery, L.; Ständer, S.; Szepietowski, J.C.; Reich, A.; Wallengren, J.; Evers, A.W.; Takamori, K.; Brenaut, E.; Le Gall-Ianotto, C.; Fluhr, J.; et al. Definition of Sensitive Skin: An Expert Position Paper from the Special Interest Group on Sensitive Skin of the International Forum for the Study of Itch. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2017, 97, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Martory, C.; Roguedas-Contios, A.M.; Sibaud, V.; Degouy, A.; Schmitt, A.M.; Misery, L. Sensitive skin is not limited to the face. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 158, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, E.N.; Anzai, A.; Costa Fechine, C.O.; Sakai Valente, N.Y.; Romiti, R. Sensitive Scalp and Trichodynia: Epidemiology, Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2023, 9, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misery, L.; Rahhali, N.; Ambonati, M.; Black, D.; Saint-Martory, C.; Schmitt, A.M.; Taieb, C. Evaluation of sensitive scalp severity and symptomatology by using a new score. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2011, 25, 1295–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Tapia, A.; González-Guerra, E. Sensitive Scalp: Diagnosis and Practical Management. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 2023, 114, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanakaemakorn, P.; Suchonwanit, P. Scalp Pruritus: Review of the Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1268430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ständer, S.; Weisshaar, E.; Mettang, T.; Szepietowski, J.C.; Carstens, E.; Ikoma, A.; Bergasa, N.V.; Gieler, U.; Misery, L.; Wallengren, J.; et al. Clinical classification of itch: A position paper of the International Forum for the Study of Itch. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2007, 87, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, K.; Schwartz, J.R.; Filloon, T.; Fieno, A.; Wehmeyer, K.; Szepietowski, J.C.; Mills, K.J. Scalp stratum corneum histamine levels: Novel sampling method reveals association with itch resolution in dandruff/seborrhoeic dermatitis treatment. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2011, 91, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, J.L.; Chan, Y.H.; Rapp, S.R.; Yosipovitch, G. Differences in itch characteristics between psoriasis and atopic dermatitis patients: Results of a web-based questionnaire. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2011, 91, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piérard-Franchimont, C.; Hermanns, J.F.; Degreef, H.; Piérard, G.E. From axioms to new insights into dandruff. Dermatology 2000, 200, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scribner, M. Diabetes and pruritus of the scalp. JAMA 1977, 237, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oaklander, A.L.; Bowsher, D.; Galer, B.; Haanpää, M.; Jensen, M.P. Herpes zoster itch: Preliminary epidemiologic data. J. Pain 2003, 4, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhard, J.D. The itchy scalp. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 176, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beare, J.M. Generalized pruritus. A study of 43 cases. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1976, 1, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferm, I.; Sterner, M.; Wallengren, J. Somatic and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic pruritus. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2010, 90, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumway, N.K.; Cole, E.; Fernandez, K.H. Neurocutaneous disease: Neurocutaneous dysesthesias. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 74, 215–228; quiz 229–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noli, C.; Morelli, G.; Della Valle, M.F.; Schievano, C.; Skinalia Clinical Research, G. Effects of a Protocol Combining a Non-Irritating Shampoo and an Adelmidrol-Based Adsorbent Mousse on Seborrhoea and Other Signs and Symptoms Secondary to Canine Atopic Dermatitis: A Multicenter, Open-Label Uncontrolled Clinical Trial. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Guichard, A.; Humbert, P.; Zheng, S.; Tan, Y.; Yu, L.; Qin, O.; Wang, X. Evaluation of the severity and triggering factors of sensitive scalp in Chinese females. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2016, 15, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misery, L.; Sibaud, V.; Ambronati, M.; Macy, G.; Boussetta, S.; Taieb, C. Sensitive scalp: Does this condition exist? An epidemiological study. Contact Dermat. 2008, 58, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.H.; Kim, J.; Oh, B.; Lee, E.; Hwang-Bo, J.; Ha, J. Evaluation of factors triggering sensitive scalp in Korean adult women. Ski. Res. Technol. 2019, 25, 862–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Guichard, A.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Qin, O.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Tan, Y. Sensitive scalp is associated with excessive sebum and perturbed microbiome. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2019, 18, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampe, M.A.; Burlingame, A.L.; Whitney, J.; Williams, M.L.; Brown, B.E.; Roitman, E.; Elias, P.M. Human stratum corneum lipids: Characterization and regional variations. J. Lipid Res. 1983, 24, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maglie, R.; Souza Monteiro de Araujo, D.; Antiga, E.; Geppetti, P.; Nassini, R.; De Logu, F. The Role of TRPA1 in Skin Physiology and Pathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, B.I.; Oláh, A.; Szöllősi, A.G.; Bíró, T. TRP channels in the skin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 2568–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes-Rodriguez, R.; Kaushik, S.B.; Yosipovitch, G. Transient receptor potential channels and dermatological disorders. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imokawa, G.; Abe, A.; Jin, K.; Higaki, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Hidano, A. Decreased level of ceramides in stratum corneum of atopic dermatitis: An etiologic factor in atopic dry skin? J. Investig. Dermatol. 1991, 96, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungersted, J.M.; Scheer, H.; Mempel, M.; Baurecht, H.; Cifuentes, L.; Høgh, J.K.; Hellgren, L.I.; Jemec, G.B.; Agner, T.; Weidinger, S. Stratum corneum lipids, skin barrier function and filaggrin mutations in patients with atopic eczema. Allergy 2010, 65, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuth, M.; Eckmann, S.; Moosbrugger-Martinz, V.; Ortner-Tobider, D.; Blunder, S.; Trafoier, T.; Gruber, R.; Elias, P.M. Skin Barrier in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 989–1000.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Kong, H.H.; Seed, P.; Naik, S.; Scharschmidt, T.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Luger, T.; Irvine, A.D. The microbiome in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka-Tomaszewska, J.; Trzeciak, M. Molecular Mechanisms of Atopic Dermatitis Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Seok, J.K.; Kang, H.C.; Cho, Y.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.Y. Skin Barrier Abnormalities and Immune Dysfunction in Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda, L.J.; Wikramanayake, T.C. Seborrheic Dermatitis and Dandruff: A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolhiser, E.; Keime, N.; Patel, A.; Weber, I.; Adelman, M.; Dellavalle, R.P. Nutrition, Obesity, and Seborrheic Dermatitis: Systematic Review. JMIR Dermatol. 2024, 7, e50143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, Y.M.; Saunders, C.W.; Johnstone, K.R.; Reeder, N.L.; Coleman, C.G.; Kaczvinsky, J.R., Jr.; Gale, C.; Walter, R.; Mekel, M.; Lacey, M.P.; et al. Isolation and expression of a Malassezia globosa lipase gene, LIP1. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127, 2138–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, L.I.; Squiquera, L.; Mathov, I.; Galimberti, R.; Leoni, J. Characterization of the lipase activity of Malassezia furfur. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 1996, 34, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudramurthy, S.M.; Honnavar, P.; Dogra, S.; Yegneswaran, P.P.; Handa, S.; Chakrabarti, A. Association of Malassezia species with dandruff. Indian J. Med. Res. 2014, 139, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eyerich, S.; Eyerich, K.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Biedermann, T. Cutaneous Barriers and Skin Immunity: Differentiating A Connected Network. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroni, A.G.; Trave, I.; Herzum, A.; Parodi, A. Sensitive scalp: An epidemiologic study in patients with hair loss. Dermatol. Rep. 2022, 14, 9408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicherts, P.; Wiemer, J.; Gerdes, A.B.M.; Schulz, S.M.; Pauli, P.; Wieser, M.J. Anxious anticipation and pain: The influence of instructed vs conditioned threat on pain. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2017, 12, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besné, I.; Descombes, C.; Breton, L. Effect of age and anatomical site on density of sensory innervation in human epidermis. Arch. Dermatol. 2002, 138, 1445–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenske, N.A.; Lober, C.W. Structural and functional changes of normal aging skin. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1986, 15 Pt 1, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luebberding, S.; Krueger, N.; Kerscher, M. Age-related changes in skin barrier function—Quantitative evaluation of 150 female subjects. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2013, 35, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.; Harding, C.; Mayo, A.; Banks, J.; Rawlings, A. Stratum corneum lipids: The effect of ageing and the seasons. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1996, 288, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florence, P.; Cornillon, C.; D’Arras, M.-F.; Flament, F.; Panhard, S.; Diridollou, S.; Loussouarn, G. Functional and structural age-related changes in the scalp skin of Caucasian women. Ski. Res. Technol. 2013, 19, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, X.; Mao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Mei, X.; Shi, W. Variation of biophysical parameters of the skin with age, gender, and lifestyles. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagami, H. Functional characteristics of the stratum corneum in photoaged skin in comparison with those found in intrinsic aging. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2008, 300 (Suppl. 1), S1–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passeron, T.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Tan, J.; Andersen, M.L.; Katta, R.; Lyu, X.; Aguilar, L.; Kerob, D.; Morita, A.; Krutmann, J.; et al. Adult skin acute stress responses to short-term environmental and internal aggression from exposome factors. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2021, 35, 1963–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas-Taberner, J.; González-Guerra, E.; Guerra-Tapia, A. Sensitive skin: A complex syndrome. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 2011, 102, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misery, L.; Myon, E.; Martin, N.; Consoli, S.; Boussetta, S.; Nocera, T.; Taieb, C. Sensitive skin: Psychological effects and seasonal changes. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2007, 21, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Guiraud, A. Sensitive skin: A complex and multifactorial syndrome. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2004, 3, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafiriou, E.; Angelopoulos, N.V.; Zintzaras, E.; Rallis, E.; Roussaki-Schulze, A.V. Psychiatric factors in patients with sensitive skin. Drugs Under Exp. Clin. Res. 2005, 31, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Godse, K.; Zawar, V. Sensitive scalp. Int. J. Trichology 2012, 4, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manav, V.; Karaali, M.G.; Erdem, O.; Koku Aksu, A.E. Association between biophysical properties and anxiety in patients with sensitive skin. Ski. Res. Technol. 2022, 28, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askin, O.; Gok, A.M.; Serdaroglu, S. Presence of Trichodynia Symptoms in Hair Diseases and Related Factors. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2021, 7, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebora, A. Trichodynia: A review of the literature. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenaut, E.; Misery, L.; Legeas, C.; Roudot, A.C.; Ficheux, A.S. Sensitive Scalp: A Possible Association With the Use of Hair Conditioners. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 596544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlGhamdi, K.M.; Moussa, N.A. Local side effects caused by hair dye use in females: Cross-sectional survey. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2012, 16, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, J.F. Hair coloring. Clin. Dermatol. 1988, 6, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søsted, H.; Hesse, U.; Menné, T.; Andersen, K.E.; Johansen, J.D. Contact dermatitis to hair dyes in a Danish adult population: An interview-based study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005, 153, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, E.S.; Novick, R.M.; Drechsel, D.A.; Towle, K.M.; Paustenbach, D.J.; Monnot, A.D. Tier-based skin irritation testing of hair cleansing conditioners and their constituents. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2019, 38, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavazzoni Dias, M.F. Hair cosmetics: An overview. Int. J. Trichology 2015, 7, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnot, A.D.; Towle, K.M.; Warshaw, E.M.; Fung, E.S.; Novick, R.M.; Paustenbach, D.J.; Drechsel, D.A. Skin Sensitization Induction Risk Assessment of Common Ingredients in Commercially Available Cleansing Conditioners. Dermatitis 2019, 30, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, C.T.; Juhasz, M.; Lin, J.; Hashemi, K.; Honari, G.; Mesinkovska, N.A. Allergic Contact Dermatitis of the Scalp Associated With Scalp Applied Products: A Systematic Review of Topical Allergens. Dermatitis 2022, 33, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punyani, S.; Tosti, A.; Hordinsky, M.; Yeomans, D.; Schwartz, J. The Impact of Shampoo Wash Frequency on Scalp and Hair Conditions. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2021, 7, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, U.; Koop, U.; Leneveu-Duchemin, M.C.; Osterrieder, K.; Bielfeldt, S.; Chkarnat, C.; Degwert, J.; Häntschel, D.; Jaspers, S.; Nissen, H.P.; et al. Multicentre comparison of skin hydration in terms of physical-, physiological- and product-dependent parameters by the capacitive method (Corneometer CM 825). Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2003, 25, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdain, R.; Moga, A.; Vingler, P.; El Rawadi, C.; Pouradier, F.; Souverain, L.; Bastien, P.; Amalric, N.; Breton, L. Exploration of scalp surface lipids reveals squalene peroxide as a potential actor in dandruff condition. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2016, 308, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavaud, C.; Jourdain, R.; Bar-Hen, A.; Tichit, M.; Bouchier, C.; Pouradier, F.; El Rawadi, C.; Guillot, J.; Ménard-Szczebara, F.; Breton, L.; et al. Dandruff is associated with disequilibrium in the proportion of the major bacterial and fungal populations colonizing the scalp. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, Y.M.; Gemmer, C.M.; Kaczvinsky, J.R.; Kenneally, D.C.; Schwartz, J.R.; Dawson, T.L., Jr. Three etiologic facets of dandruff and seborrheic dermatitis: Malassezia fungi, sebaceous lipids, and individual sensitivity. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2005, 10, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, B.I.; Dawson, T.L. The role of sebaceous gland activity and scalp microfloral metabolism in the etiology of seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2005, 10, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.M.; Boussouira, B.; Moyal, D.; Nguyen, Q.L. Oxidization of squalene, a human skin lipid: A new and reliable marker of environmental pollution studies. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2015, 37, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, P.; Nandar, S.K.; Kathuria, S.; Ramesh, V. Effects of air pollution on the skin: A review. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2017, 83, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, W. Air pollution and skin disorders. Int. J. Women’s Dermatol. 2021, 7, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollenberg, A.; Giménez-Arnau, A. Sensitive skin: A relevant syndrome, be aware. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2022, 36 (Suppl. 5), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A.; Stolz, H.J.; Sonsmann, F.K. Mild but effective skin cleansing-Evaluation of laureth-23 as a primary surfactant. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2024, 46, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosrowpour, Z.; Ahmad Nasrollahi, S.; Samadi, A.; Ayatollahi, A.; Shamsipour, M.; Rajabi-Esterabadi, A.; Yadangi, S.; Firooz, A. Skin biophysical assessments of four types of soaps by forearm in-use test. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 3127–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trüeb, R.M. North American Virginian Witch Hazel (Hamamelis virginiana): Based Scalp Care and Protection for Sensitive Scalp, Red Scalp, and Scalp Burn-Out. Int. J. Trichology 2014, 6, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, P.; Rathi, S.K. Shampoo and Conditioners: What a Dermatologist Should Know? Indian J. Dermatol. 2015, 60, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatsbach de Paula, J.N.; Basílio, F.M.A.; Mulinari-Brenner, F.A. Effects of chemical straighteners on the hair shaft and scalp. An. Bras. De Dermatol. 2022, 97, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, J.L.; Muñoz-Rodriguez, J.R.; Cruz-Morcillo, M.A.; Villar-Rodriguez, C.; Gonzalez-Lopez, L.; Aguado, C.; Nuncia-Cantarero, M.; Redondo-Calvo, F.J.; Perez-Ortiz, J.M.; Galan-Moya, E.M. Characterization of Permeability Barrier Dysfunction in a Murine Model of Cutaneous Field Cancerization Following Chronic UV-B Irradiation: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Skin Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.Z.J.; Lim, F.C.; Tey, H.L. Clinical efficacy of a gentle anti-dandruff itch-relieving shampoo formulation. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2023, 45, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draelos, Z.D.; Baalbaki, N.; Colon, G.; Dreno, B. Ceramide-Containing Adjunctive Skin Care for Skin Barrier Restoration During Acne Vulgaris Treatment. J. Drugs Dermatol. JDD 2023, 22, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, L.H.D.; Azizi, N.; Maibach, H. Sensitive Skin Syndrome: An Update. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 21, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissonnette, R.; Risch, J.E.; McElwee, K.J.; Marchessault, P.; Bolduc, C.; Nigen, S.; Maari, C. Changes in serum free testosterone, sleep patterns, and 5-alpha-reductase type I activity influence changes in sebum excretion in female subjects. Ski. Res. Technol. 2015, 21, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xerfan, E.M.S.; Tomimori, J.; Andersen, M.L.; Tufik, S.; Facina, A.S. Sleep disturbance and atopic dermatitis: A bidirectional relationship? Med. Hypotheses 2020, 140, 109637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmert, H.; Baurecht, H.; Thielking, F.; Stölzl, D.; Rodriguez, E.; Harder, I.; Proksch, E.; Weidinger, S. Stratum corneum lipidomics analysis reveals altered ceramide profile in atopic dermatitis patients across body sites with correlated changes in skin microbiome. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 1398–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.B.; Alexander, H.; Um, J.Y.; Chung, B.Y.; Park, C.W.; Flohr, C.; Kim, H.O. Skin Microbiome Dynamics in Atopic Dermatitis: Understanding Host-Microbiome Interactions. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2025, 17, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousel, J.; Nădăban, A.; Saghari, M.; Pagan, L.; Zhuparris, A.; Theelen, B.; Gambrah, T.; van der Wall, H.E.C.; Vreeken, R.J.; Feiss, G.L.; et al. Lesional skin of seborrheic dermatitis patients is characterized by skin barrier dysfunction and correlating alterations in the stratum corneum ceramide composition. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e14952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wen, X.; Hou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Song, W.; Zeng, Y.; Sun, J. Integrated metabolomics and lipidomics study of patients with atopic dermatitis in response to dupilumab. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1002536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; He, C.F.; Fan, L.N.; Jia, Y. Application of lipidomics to reveal differences in facial skin surface lipids between males and females. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2018, 17, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Jia, Y.; Cheng, Z.W.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, G.L.; Li, J.Y.; He, C.F. Advancements in the maintenance of skin barrier/skin lipid composition and the involvement of metabolic enzymes. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2016, 15, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Jia, Y. Application of omics technologies in dermatological research and skin management. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Gan, Y.; He, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, C. The mechanism of skin lipids influencing skin status. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2018, 89, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Zhou, M.; Huang, H.; Gan, Y.; Yang, M.; Ding, R. Characterization of circadian human facial surface lipid composition. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 858–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Jia, Y.; He, C. Promoting new concepts of skincare via skinomics and systems biology-From traditional skincare and efficacy-based skincare to precision skincare. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2018, 17, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cui, L.; Tian, Y.; He, C. Lipidomics analysis of facial lipid biomarkers in females with self-perceived skin sensitivity. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cui, L.; Jia, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, G.; He, C. Application of lipidomics to reveal differences of facial skin surface lipids between atopic dermatitis and healthy infants. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M.; Jia, Y.; Yang, M.; He, C. Prediction of neonatal acne based on maternal lipidomic profiling. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 2759–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Jia, Y. Lipidomic analysis of facial skin surface lipid reveals the causes of pregnancy-related skin barrier weakness. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Yang, M.; Gao, Y.; Jia, Y. Lipidomics reveals the role of glycoceramide and phosphatidylethanolamine in infantile acne. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liang, H.; Li, Z.; Tang, M.; Song, L. Skin microbiome in sensitive skin: The decrease of Staphylococcus epidermidis seems to be related to female lactic acid sting test sensitive skin. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2020, 97, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhou, M.; Song, L.; He, C. Skin bacterial structure of young females in China: The relationship between skin bacterial structure and facial skin types. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 1366–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ma, L.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Cui, S.; Liang, H.; He, C.; Song, L. Alterations in the skin microbiome are associated with disease severity and treatment in the perioral zone of the skin of infants with atopic dermatitis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 1677–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ma, L.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Cui, S.; Liang, H.; Song, L.; He, C. Shifts in the skin microbiome associated with diaper dermatitis and emollient treatment amongst infants and toddlers in China. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Gan, Y.; He, C.; Chen, Z.; Jia, Y. Lipidomics reveals skin surface lipid abnormity in acne in young men. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 179, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Gan, Y.; Yang, M.; He, C.; Jia, Y. Lipidomics analysis of facial skin surface lipids between forehead and cheek: Association between lipidome, TEWL, and pH. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 2752–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Yang, M.; He, C.; Yang, M.; Gao, Y.; Jia, Y. Lipidomic analysis of facial skin surface lipids reveals an altered lipid profile in infant acne. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Yang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Dong, K.; Song, L.; He, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Jia, Y. Skin surface lipidomics revealed the correlation between lipidomic profile and grade in adolescent acne. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 3349–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).