The Importance of Cosmetics in Oncological Patients. Survey of Tolerance of Routine Cosmetic Care in Oncological Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

3. Results

3.1. Surveys on the Management of Cosmetic Skin Care Regimens and the Quality of Life of Oncological Patients

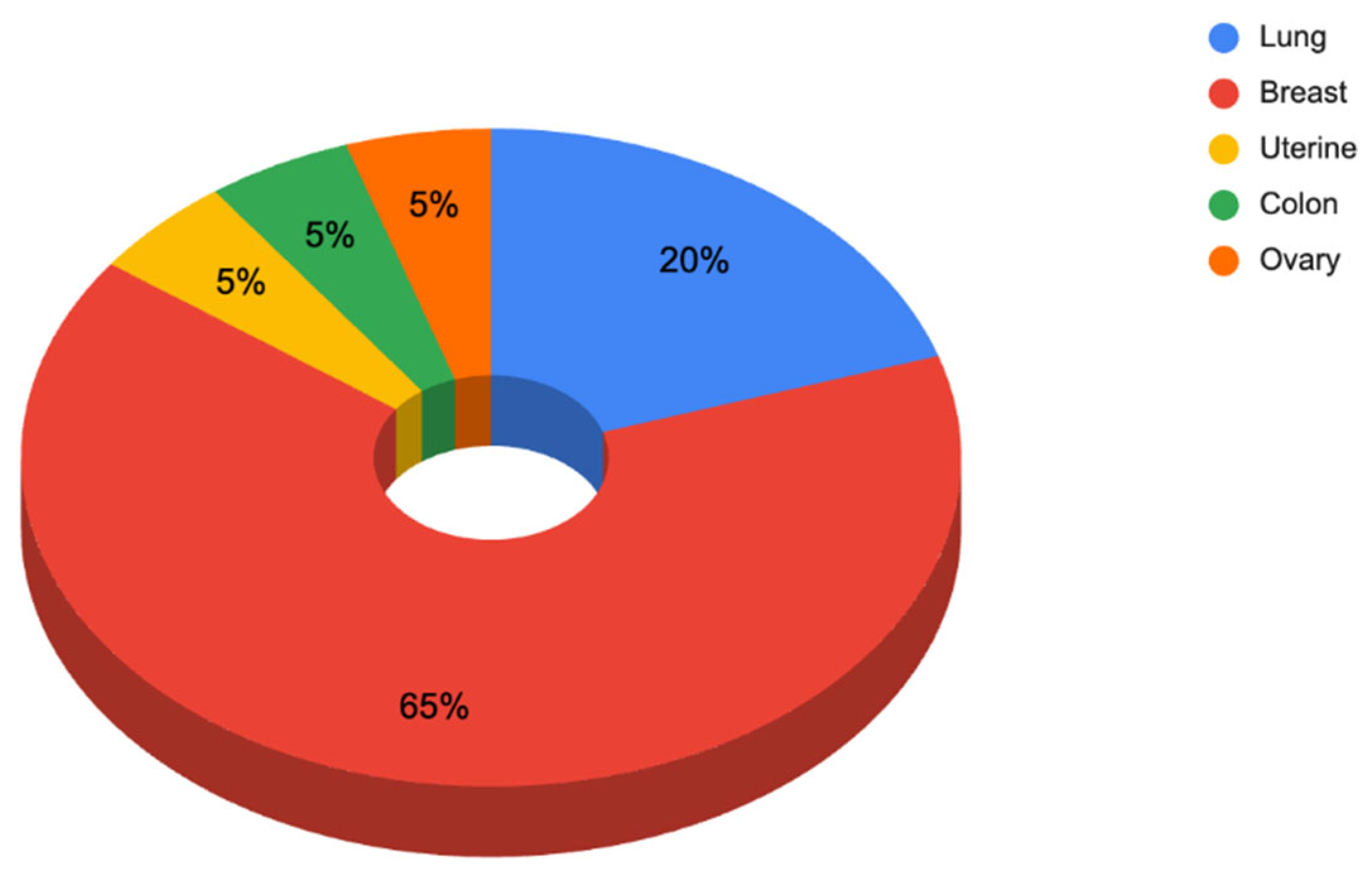

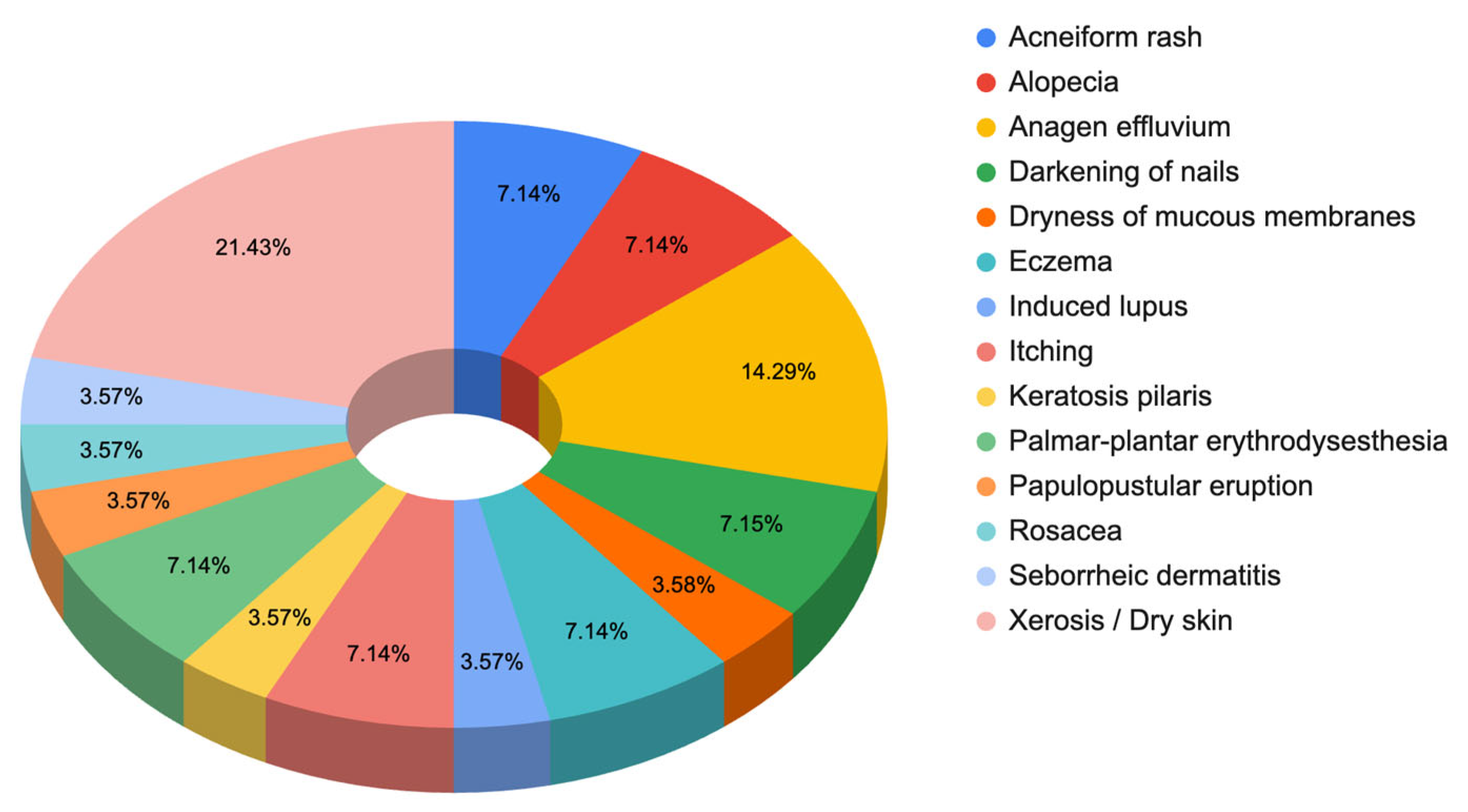

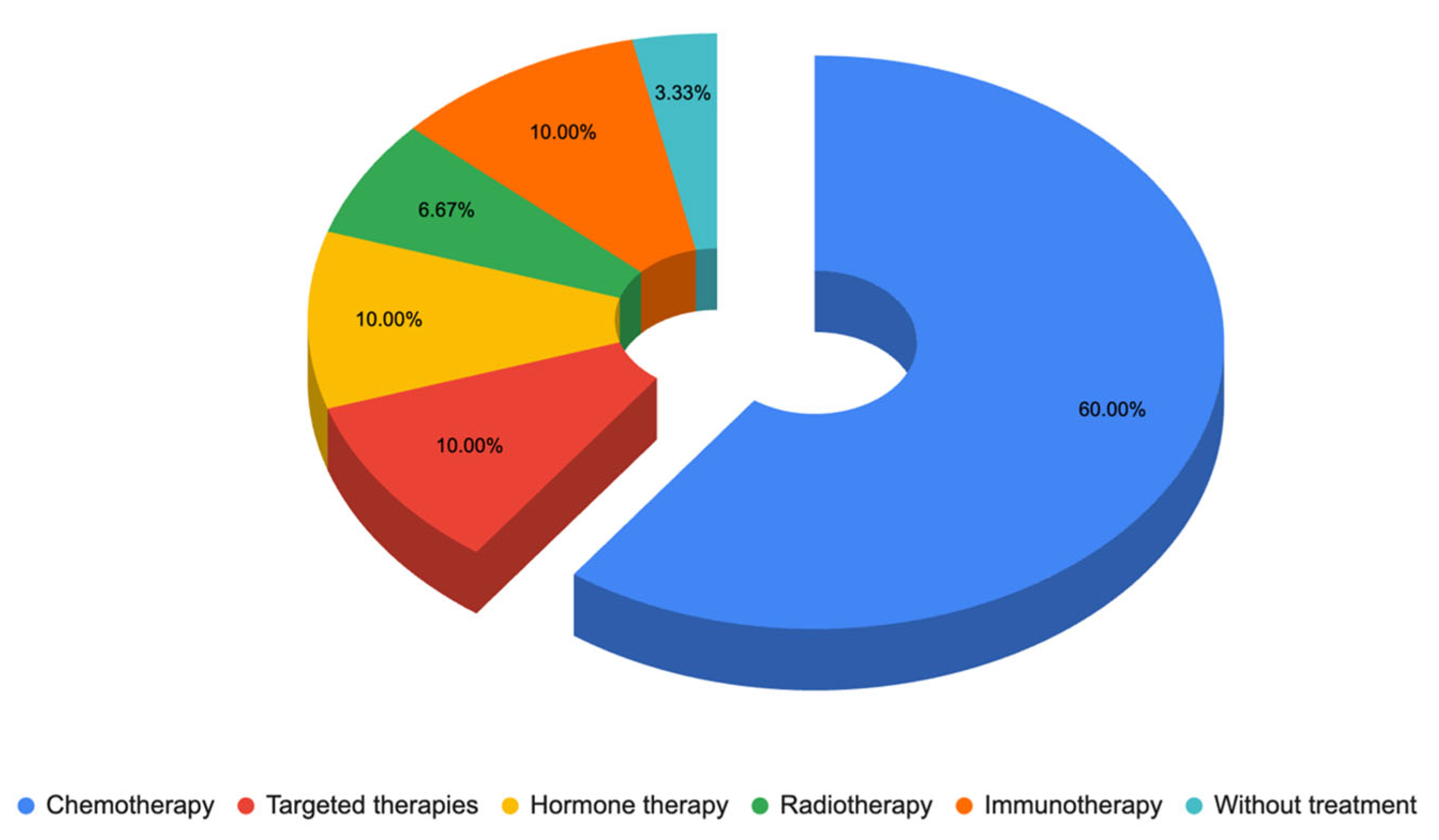

3.1.1. Responses to Questionnaire C—Dermatologist Questionnaire

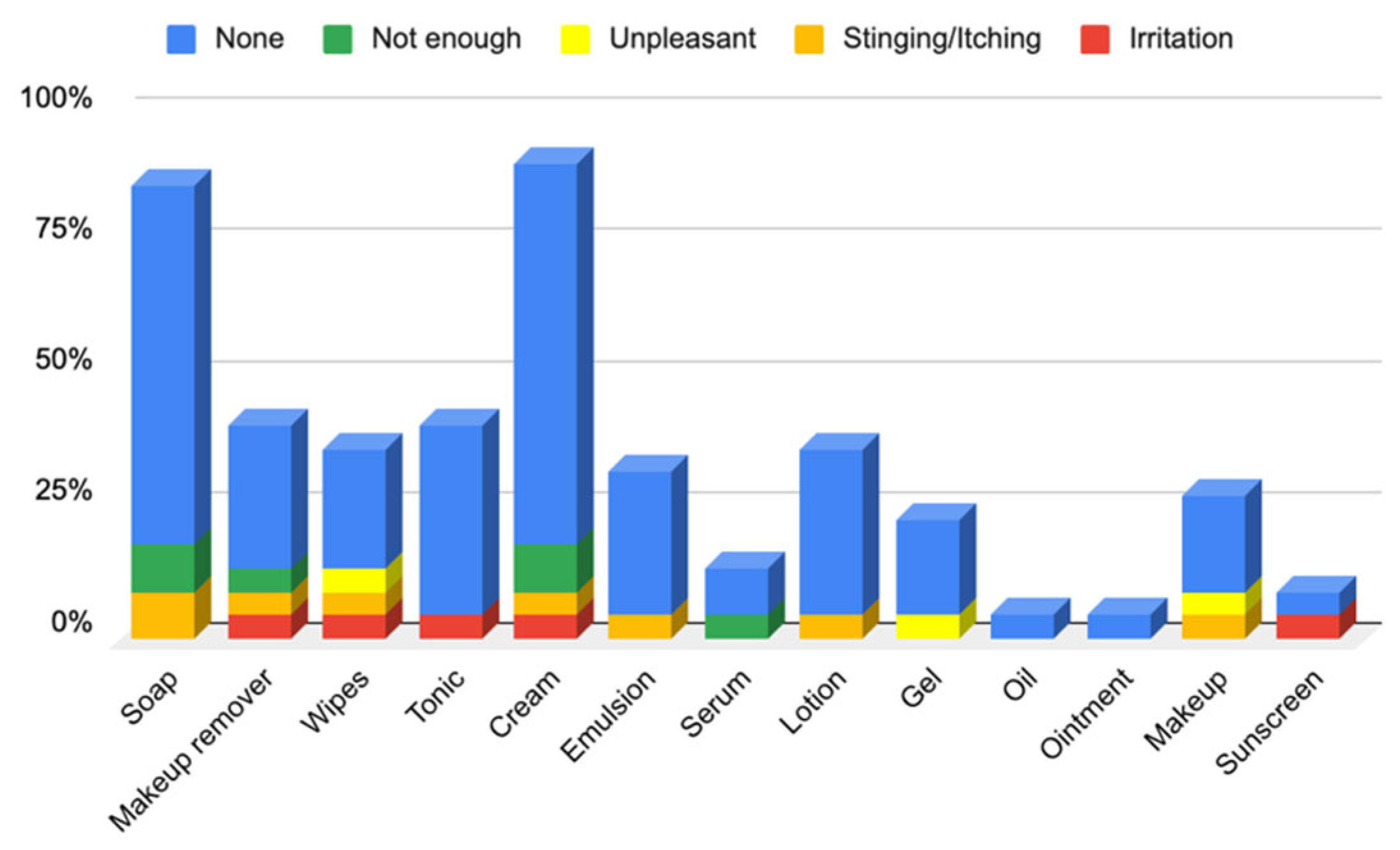

3.1.2. Responses to Questionnaire B—Cosmetic Skin Care Management

Responses to Section 3: Symptoms and/or Dermatological Problems at the Present Time, by Areas (Facial Area, Hair Area, Scalp Area, and Nails)

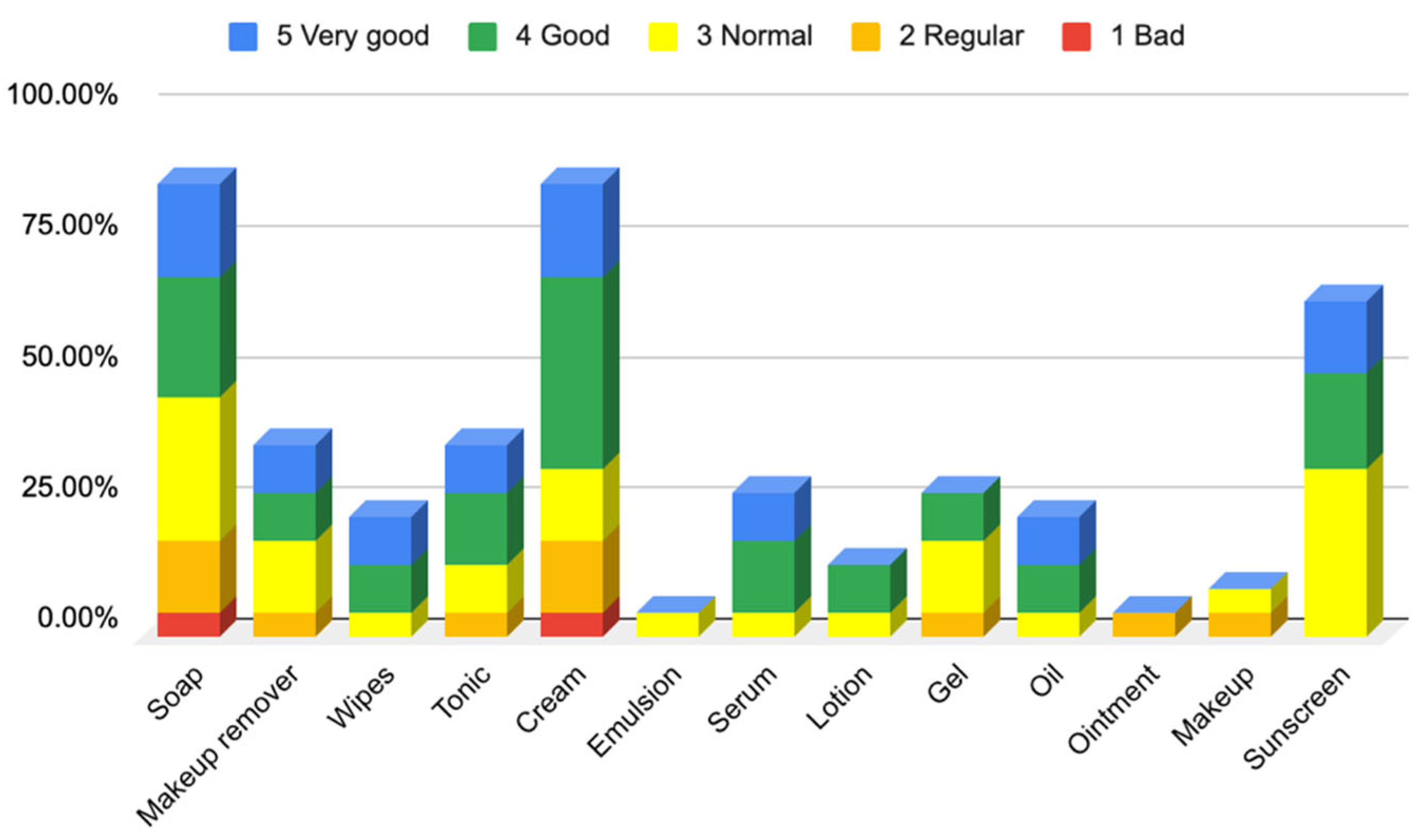

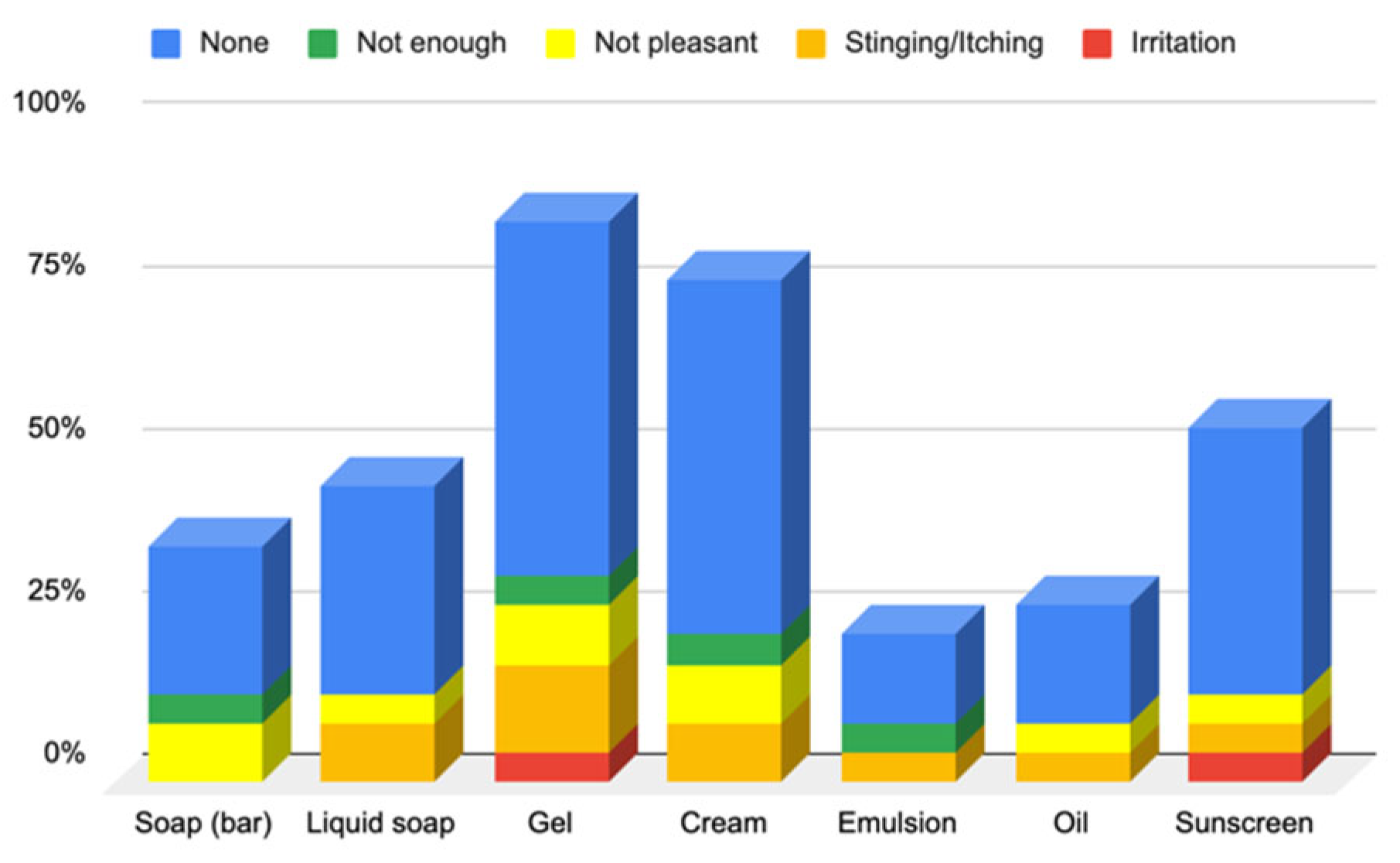

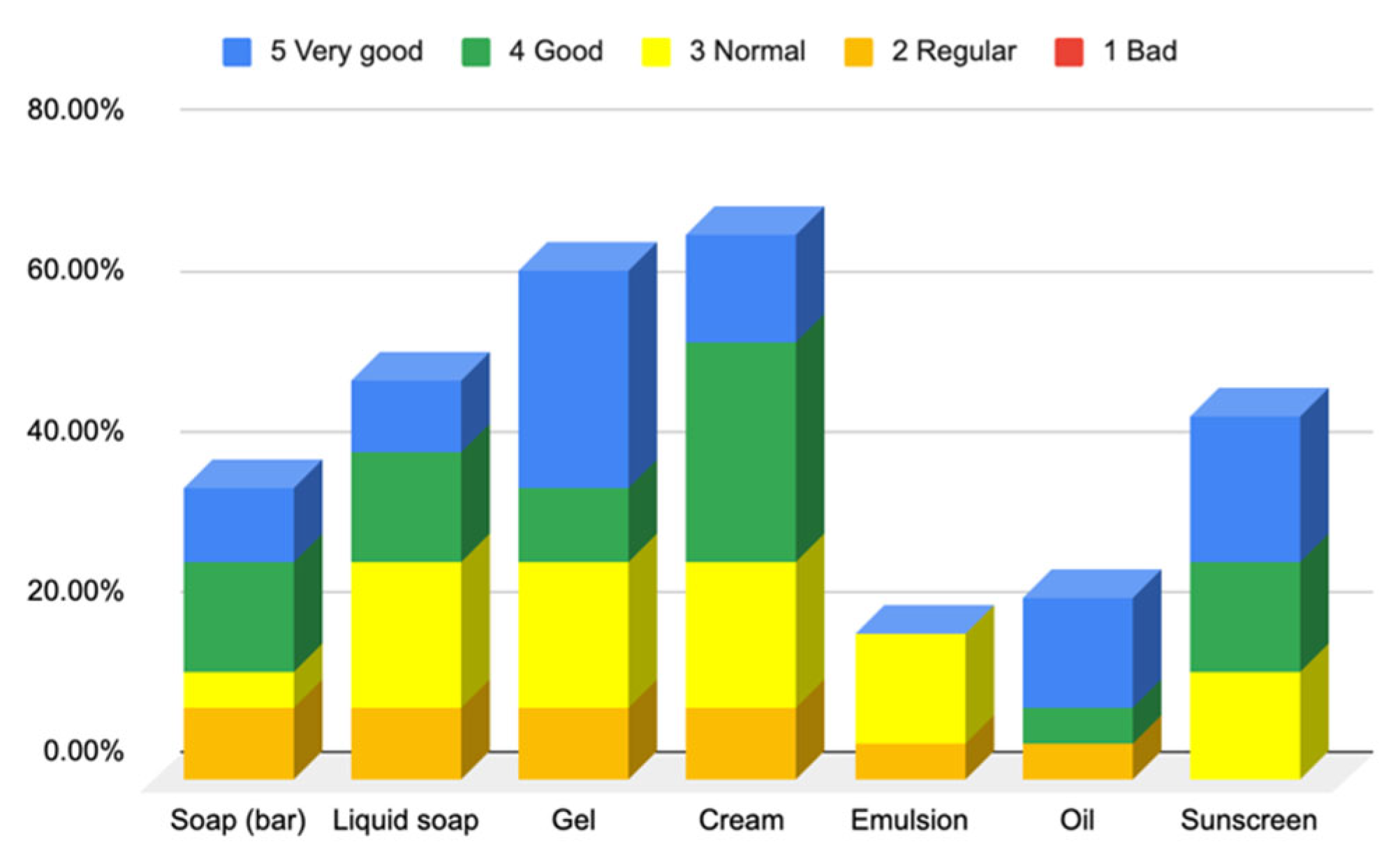

Responses to Section 4: Cosmetic Skin Care Management Cosmetic Habits (Hygiene and Hydrating) in the Facial Area

Responses to Section 5: Cosmetic Skin Care Management Cosmetic Habits (Hygiene and Hydrating) in the Body Area and Hands

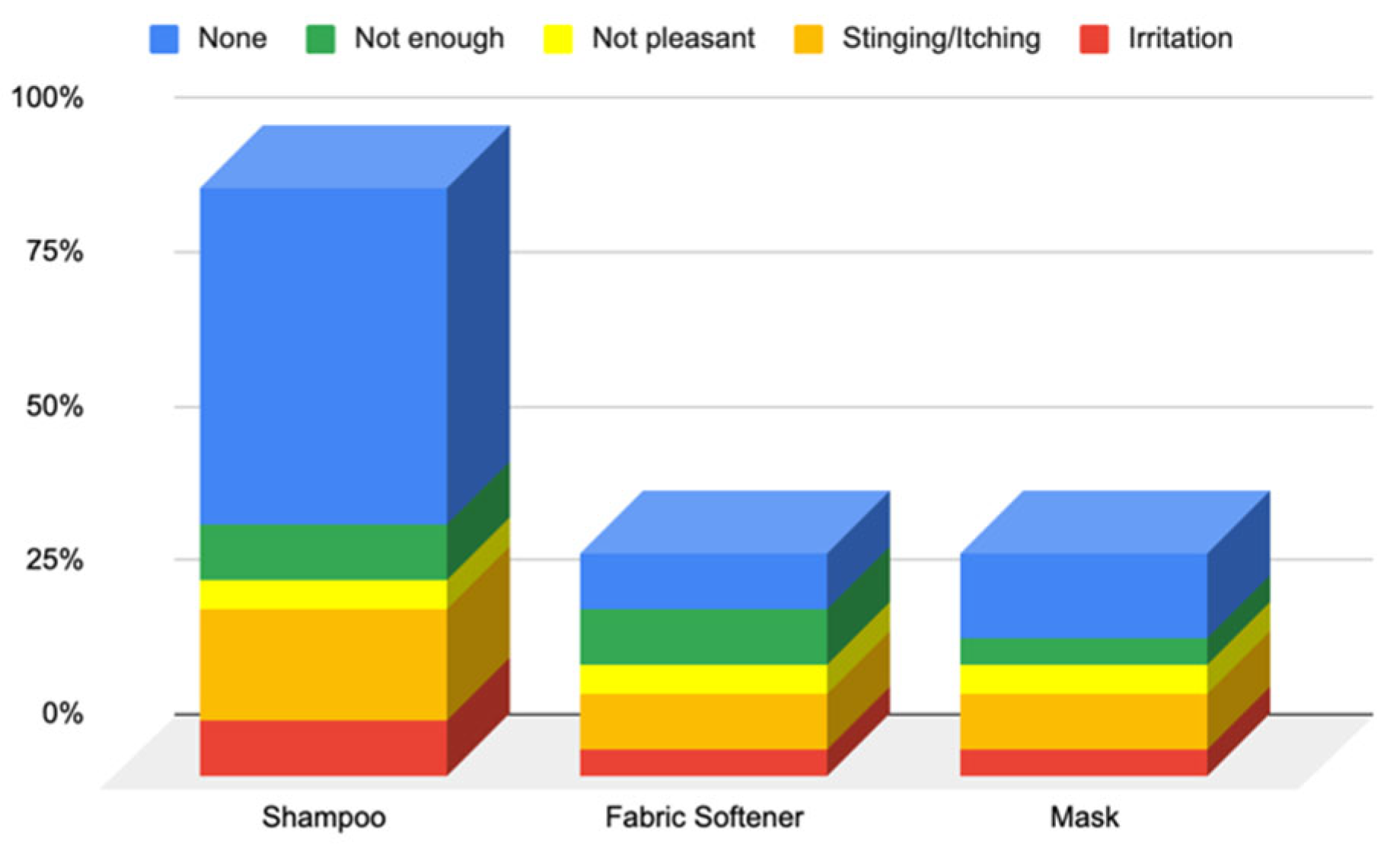

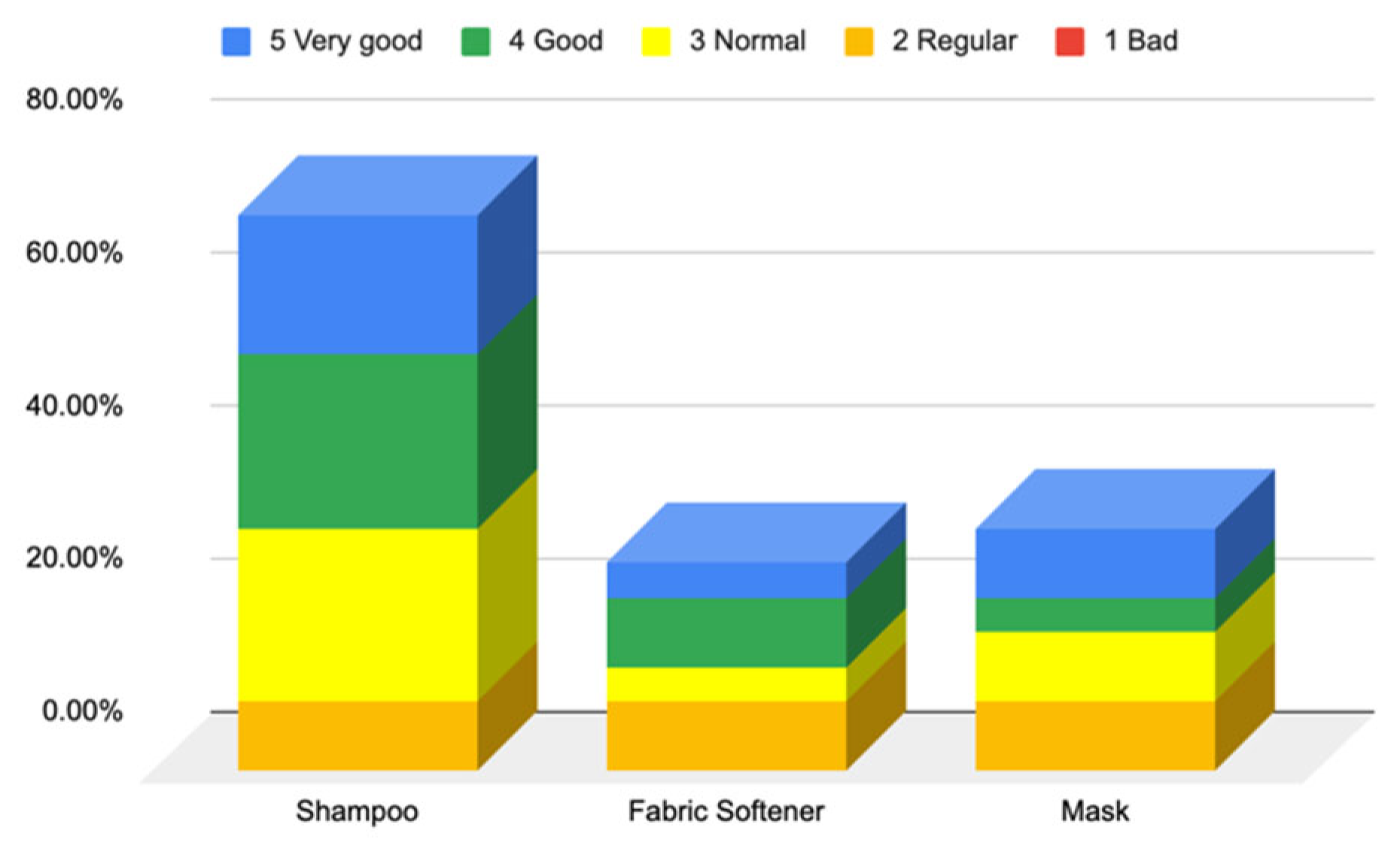

Responses to Section 6: Cosmetic Skin Care Management Cosmetic Habits (Hygiene and Hydrating) in the Hair Area and Scalp

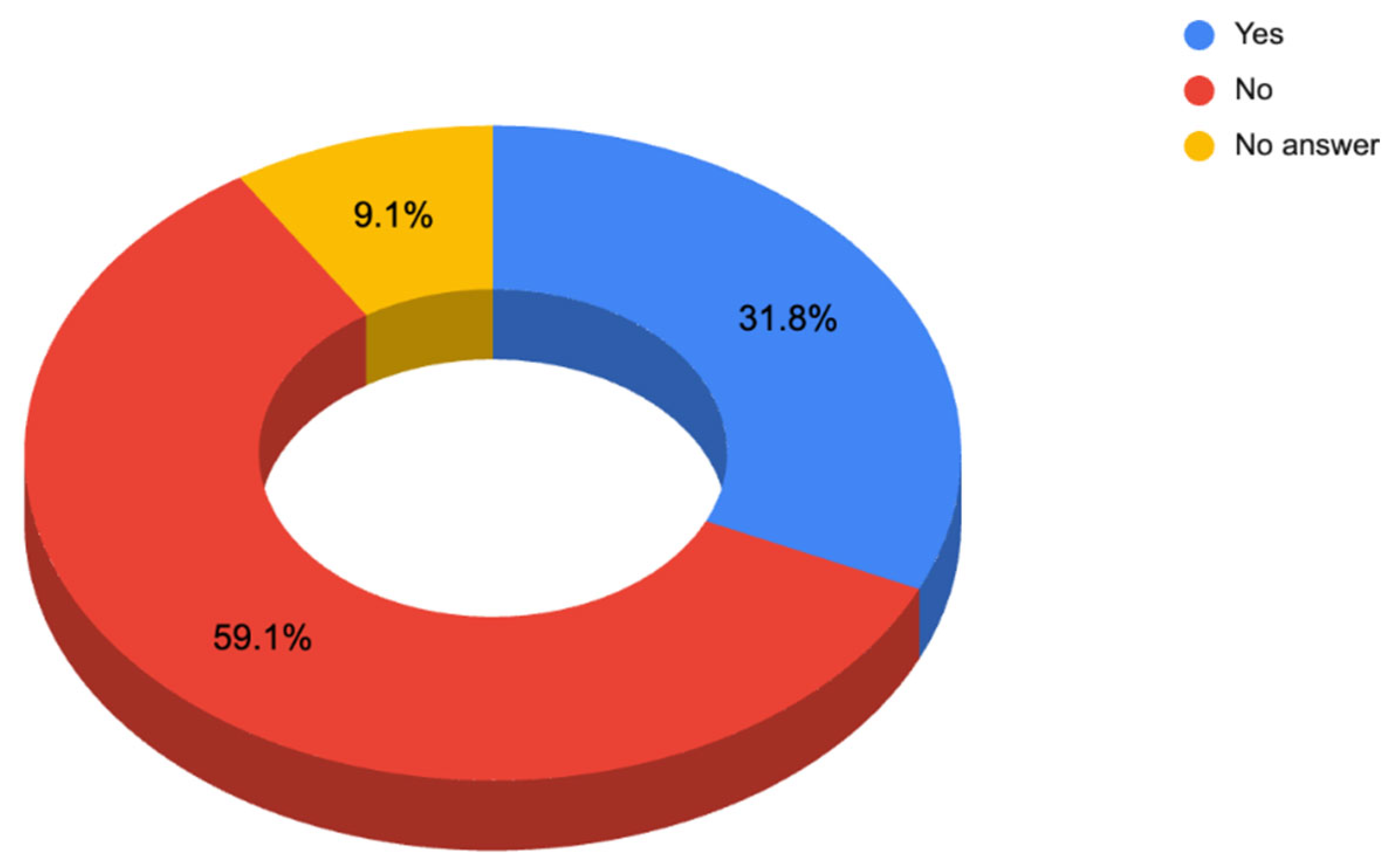

Responses to the Questions on Cosmetic Purchasing Behavior (Questionnaire B—Cosmetic Skin Care Management, Section 7)

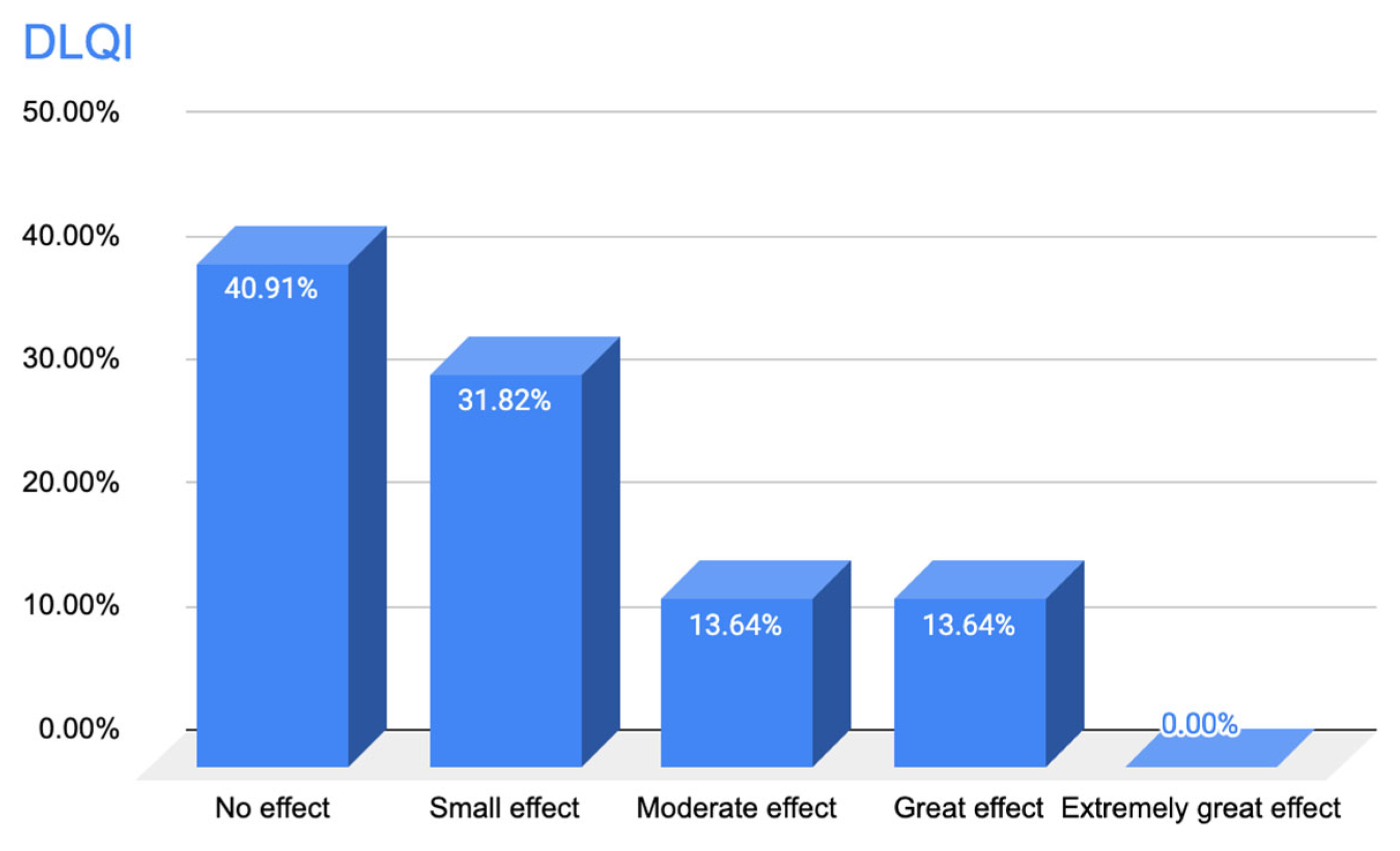

3.1.3. Results of Responses to Questionnaire A—Quality of Life Questionnaire

4. Discussion

The Importance of Cosmetics in Oncological Patients

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, L.; Adique, A.; Sarkar, P.; Shenai, V.; Sampath, M.; Lai, R.; Qi, J.; Wang, M.; Farage, M.A. The Impact of Routine Skin Care on the Quality of Life. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira-Junior, I.; da Silva, F.C.B.; Nazima, F.; Jr, J.C.R.; Castellani, L.; Zucca-Matthes, G.; Maciel, M.D.S.; Biller, G.; da Silva, J.J.; Sarri, A.J.; et al. Oncoplastic Surgery: Does Patient and Medical Specialty Influences the Evaluation of Cosmetic Results? Clin. Breast Cancer 2021, 21, 247.e3–255.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flament, F.; Jiang, R.; Delaunay, C.; Kerob, D.; Leclerc-Mercier, S.; Kosmadaki, M.; Roó, E.; Haag, T.; Passeron, T.; Zouboulis, C.C. Evaluation of Adapted Dermocosmetic Regimens for Perimenopausal and Menopausal Women Using an Artificial Intelligence-based Algorithm and Quality of Life Questionnaires: An Open Observational Study. Ski. Res. Technol. 2023, 29, e13349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollenberg, A.; Barbarot, S.; Bieber, T.; Christen-Zaech, S.; Deleuran, M.; Fink-Wagner, A.; Gieler, U.; Girolomoni, G.; Lau, S.; Muraro, A.; et al. Consensus-Based European Guidelines for Treatment of Atopic Eczema (Atopic Dermatitis) in Adults and Children: Part I. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 657–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobkowska, D.; Szałapska, A.; Pawlaczyk, M.; Urbańska, M.; Micek, I.; Wróblewska-Kończalik, K.; Sobkowska, J.; Jałowska, M.; Gornowicz-Porowska, J. The Role of Cosmetology in an Effective Treatment of Rosacea: A Narrative Review. CCID 2023, 16, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, M.; Sander, M.; Burbidge, T.; Beecker, J. The Efficacy and Safety of Sunscreen Use for the Prevention of Skin Cancer. CMAJ 2020, 192, E1802–E1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestari, S.; Correia, P.; Kerob, D. Emollients “Plus” are Beneficial in Both the Short and Long Term in Mild Atopic Dermatitis. CCID 2023, 16, 2093–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreno, B.; Khosrotehrani, K.; De Barros Silva, G.; Wolf, J.R.; Kerob, D.; Trombetta, M.; Atenguena, E.; Dielenseger, P.; Pan, M.; Scotte, F.; et al. The Role of Dermocosmetics in the Management of Cancer-Related Skin Toxicities: International Expert Consensus. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauder, M.B.; Andriessen, A.; Claveau, J.; Hijal, T.; Lynde, C.W. Canadian Skin Management in Oncology (CaSMO) Algorithm for Patients with Oncology Treatment-Related Skin Toxicities. Ski. Ther. Lett. 2021, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A.; Regueiro, C.; Hijal, T.; Pasquier, D.; De La Fuente, C.; Le Tinier, F.; Coche-Dequeant, B.; Lartigau, E.; Moyal, D.; Seité, S.; et al. Interest of Supportive and Barrier Protective Skin Care Products in the Daily Prevention and Treatment of Cutaneous Toxicity During Radiotherapy for Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer 2018, 12, 1178223417752772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceglio, W.Q.G.W.; Rebeis, M.M.; Santana, M.F.; Miyashiro, D.; Cury-Martins, J.; Sanches, J.A. Cutaneous Adverse Events to Systemic Antineoplastic Therapies: A Retrospective Study in a Public Oncologic Hospital. Bras. Dermatol. 2022, 97, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curkovic, N.B.; Bai, K.; Ye, F.; Johnson, D.B. Incidence of Cutaneous Immune-Related Adverse Events and Outcomes in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Containing Regimens: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2024, 16, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.; Kraft, S. Approaches to Management of Endocrine Therapy–Induced Alopecia in Breast Cancer Patients. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourelle, M.L.; Gómez, C.P.; Legido, J.L. Cosmeceuticals and Thalassotherapy: Recovering the Skin and Well-Being after Cancer Therapies. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladwa, R.; Fogarty, G.; Chen, P.; Grewal, G.; McCormack, C.; Mar, V.; Kerob, D.; Khosrotehrani, K. Management of Skin Toxicities in Cancer Treatment: An Australian/New Zealand Perspective. Cancers 2024, 16, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martín, M.-E.; Tarazona, J.V. Market Analysis of the Presence of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals in Cosmetic Products Intended for Oncological Patients and Other Vulnerable Groups. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2024, 34, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martín, M.-E.; Tarazona, J.V. Cosmetics, Endocrine Disrupting Ingredients. In Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; p. B9780128243152011854. ISBN 978-0-12-801238-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizman, L.; Nelson, K.; Sparks, A.; Friedman, A. The Influence of Supportive Oncodermatology Interventions on Patient Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Survey. JDD 2020, 19, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tischer, B.; Bilang, M.; Kraemer, M.; Ronga, P.; Lacouture, M.E. A Survey of Patient and Physician Acceptance of Skin Toxicities from Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Therapies. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andra, C.; Suwalska, A.; Dumitrescu, A.M.; Kerob, D.; Delva, C.; Hasse-Cieślińska, M.; Solymosi, A.; Arenbergerova, M. A Corrective Cosmetic Improves the Quality of Life and Skin Quality of Subjects with Facial Blemishes Caused by Skin Disorders. CCID 2020, 13, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlrab, J.; Bangemann, N.; Kleine-Tebbe, A.; Thill, M.; Kümmel, S.; Grischke, E.-M.; Richter, R.; Seite, S.; Lüftner, D. Barrier Protective Use of Skin Care to Prevent Chemotherapy-Induced Cutaneous Symptoms and to Maintain Quality of Life in Patients with Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2014, 6, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lim, J.; Park, J.S.; Kim, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kim, T.M.; Lee, K.-H.; Keam, B.; Han, S.-W.; Mun, J.-H.; et al. The Impact of Skin Problems on the Quality of Life in Patients Treated with Anticancer Agents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 50, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freites-Martinez, A.; Santana, N.; Arias-Santiago, S.; Viera, A. CTCAE versión 5.0. Evaluación de la gravedad de los eventos adversos dermatológicos de las terapias antineoplásicas. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 2021, 112, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Tiedra, A.G.; Mercadal, J.; Badía, X.; Mascaró, J.M.; Herdman, M.; Lozano, R. Adaptación transcultural al español del cuestionario Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): El Índice de Calidad de Vida en Dermatología. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 1998, 89, 692–700. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, V.; Finlay, A.Y. 10 Years Experience of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2004, 9, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belzer, A.; Pach, J.J.; Valido, K.; Leventhal, J.S. The Impact of Dermatologic Adverse Events on the Quality of Life of Oncology Patients: A Review of the Literature. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2024, 25, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.-N.; Hu, K.-C.; Wu, R.S.-C.; Bau, D.-T. Radiation-Irritated Skin and Hyperpigmentation May Impact the Quality of Life of Breast Cancer Patients after Whole Breast Radiotherapy. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilhena, F.D.M.; Pereira, O.V.; Sousa, F.d.J.D.d.; Martins, N.C.N.; Albuquerque, G.P.X.; Lopes, R.G.B.d.S.; Sagica, T.d.P.; Ramos, A.M.P.C. Factors Associated with the Quality of Life of Women Undergoing Radiotherapy. Rev. Gaúch. Enferm. 2024, 45, e20230062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grávalos, C.; Sanmartín, O.; Gúrpide, A.; España, A.; Majem, M.; Suh Oh, H.J.; Aragón, I.; Segura, S.; Beato, C.; Botella, R. Clinical Management of Cutaneous Adverse Events in Patients on Targeted Anticancer Therapies and Immunotherapies: A National Consensus Statement by the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology and the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2019, 21, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, A.C.; Case, E.C.; Dusza, S.W.; Balagula, Y.; Gordon, J.; West, D.P.; Lacouture, M.E. Impact of Dermatologic Adverse Events on Quality of Life in 283 Cancer Patients: A Questionnaire Study in a Dermatology Referral Clinic. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2013, 14, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, D.m.; Phillips, G.s.; Freites-Martinez, A.; Hsu, M.; Ciccolini, K.; Skripnik Lucas, A.; Marchetti, M.a.; Rossi, A.m.; Lee, E.h.; Deng, L.; et al. Outpatient Dermatology Consultations for Oncology Patients with Acute Dermatologic Adverse Events Impact Anticancer Therapy Interruption: A Retrospective Study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyohara, Y.; Matsuzaki, T.; Teng, L.; Kishida, M.; Kanakubo, A.; Motrunich, A.; Onishi, Y.; Igarashi, A. Drug Utilization and Medical Cost Study Focusing on Moisturizers in Cancer Patients Treated with Molecular Targeted Therapy: A Retrospective Observational Study Using Data from a Japanese Claims Database. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 1041–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.B.; Shin, M.K.; Kim, J.S.; Park, Y.L.; Oh, S.H.; Kim, D.H.; Ahn, J.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, H.O.; Kim, S.S.; et al. Perceptions and Behavior Regarding Skin Health and Skin Care Products: Analysis of the Questionnaires for the Visitors of Skin Health Expo 2018. Ann. Dermatol. 2020, 32, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cury-Martins, J.; Eris, A.P.M.; Abdalla, C.M.Z.; Silva, G.d.B.; de Moura, V.P.T.; Sanches, J.A. Management of Dermatologic Adverse Events from Cancer Therapies: Recommendations of an Expert Panel. Bras. Dermatol. 2020, 95, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacouture, M.E.; Sibaud, V.; Gerber, P.A.; van den Hurk, C.; Fernández-Peñas, P.; Santini, D.; Jahn, F.; Jordan, K. Prevention and Management of Dermatological Toxicities Related to Anticancer Agents: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behroozian, T.; Bonomo, P.; Patel, P.; Kanee, L.; Finkelstein, S.; Van Den Hurk, C.; Chow, E.; Wolf, J.R.; Behroozian, T.; Bonomo, P.; et al. Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Acute Radiation Dermatitis: International Delphi Consensus-Based Recommendations. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, e172–e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacouture, M.E.; Sibaud, V.; Anadkat, M.J.; Kaffenberger, B.; Leventhal, J.; Guindon, K.; Abou-Alfa, G. Dermatologic Adverse Events Associated with Selective Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors: Overview, Prevention, and Management Guidelines. Oncologist 2021, 26, e316–e326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacouture, M.E.; Anadkat, M.J.; Bensadoun, R.J.; Bryce, J.; Chan, A.; Epstein, J.B.; Eaby-Sandy, B.; Murphy, B.A.; Barasch, A.; Beder, C.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of EGFR Inhibitor-Associated Dermatologic Toxicities. Support. Care Cancer 2011, 19, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Abu-Sbeih, H.; Ascierto, P.A.; Brufsky, J.; Cappelli, L.C.; Cortazar, F.B.; Gerber, D.E.; Hamad, L.; Hansen, E.; Johnson, D.B.; et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Clinical Practice Guideline on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Related Adverse Events. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Anderson, R.; Blidner, A.; Cooksley, T.; Dougan, M.; Glezerman, I.; Ginex, P.; Girotra, M.; Gupta, D.; Johnson, D.; et al. Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) 2020 Clinical Practice Recommendations for the Management of Severe Dermatological Toxicities from Checkpoint Inhibitors. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 6119–6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haanen, J.B.A.G.; Carbonnel, F.; Robert, C.; Kerr, K.M.; Peters, S.; Larkin, J.; Jordan, K. Management of Toxicities from Immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, iv119–iv142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.W.; Walsh, S.M. Promoting Comfort: A Clinician Guide and Evidence-Based Skin Care Plan in the Prevention and Management of Radiation Dermatitis for Patients with Breast Cancer. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazdrowski, J.; Gornowicz-Porowska, J.; Kaźmierska, J.; Krajka-Kuźniak, V.; Polanska, A.; Masternak, M.; Szewczyk, M.; Golusiński, W.; Danczak-Pazdrowska, A. Radiation-Induced Skin Injury in the Head and Neck Region: Pathogenesis, Clinics, Prevention, Treatment Considerations and Proposal for Management Algorithm. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2024, 29, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girnita, A.; Bjerring, P.; Kauppi, S.; Lynde, C.W.; Sauder, M.B.; Andriessen, A. NECOM 3: A Practical Algorithm for the Management of Radiation Therapy-Related Acute Radiation Dermatitis. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2023, 22, S3–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, J.; Lacouture, M.; Andriessen, A.; McLellan, B.; Ho, A. United States Cutaneous Oncodermatology Management (USCOM) II: A Multidisciplinary-Guided Algorithm for the Prevention and Management of Acute Radiation Dermatitis in Cancer Patients. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2022, 21, SF3585693–SF35856914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.K.S.; Bensadoun, R.-J.; Boers-Doets, C.B.; Bryce, J.; Chan, A.; Epstein, J.B.; Eaby-Sandy, B.; Lacouture, M.E. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Acute and Late Radiation Reactions from the MASCC Skin Toxicity Study Group. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 2933–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.N.; Shah, R.; Menzer, C.; Aleisa, A.; Sun, M.D.; Kwong, B.Y.; Kaffenberger, B.H.; Seminario-Vidal, L.; Barker, C.A.; Stubblefield, M.D.; et al. Consensus on the Clinical Management of Chronic Radiation Dermatitis and Radiation Fibrosis: A Delphi Survey. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 187, 1054–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensadoun, R.-J.; Humbert, P.; Krutman, J.; Luger, T.; Triller, R.; Rougier, A.; Seite, S.; Dreno, B. Daily Baseline Skin Care in the Prevention, Treatment, and Supportive Care of Skin Toxicity in Oncology Patients: Recommendations from a Multinational Expert Panel. Cancer Manag. Res. 2013, 5, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martín, M.-E.; Tarazona, J.V. Next Generation Risk Assessment to Address Disease-Related Vulnerability—A Proof of Concept for the Sunscreen Octocrylene. Toxics 2025, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Yuan, C.; Tagmount, A.; Rudel, R.A.; Ackerman, J.M.; Yaswen, P.; Vulpe, C.D.; Leitman, D.C. Parabens and Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Ligand Cross-Talk in Breast Cancer Cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drejslarová, I.; Ječmen, T.; Hodek, P. Interaction of Perfumes with Cytochrome P-450 19. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.R.; Lin, D.A.; Maderal, A.D. Toxic Ingredients in Personal Care Products: A Dermatological Perspective. Dermatitis 2024, 35, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, M.; Gascon, M. Prenatal Exposure to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Asthma and Allergic Diseases. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 30, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathey, A.L.; Nguyen, V.K.; Colacino, J.A.; Woodruff, T.J.; Reynolds, P.; Aung, M.T. Exploratory Profiles of Phenols, Parabens, and per- and Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances among NHANES Study Participants in Association with Previous Cancer Diagnoses. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2023, 33, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Fiore, P.; Cavallin, F.; Mazza, M.; Benna, C.; Monico, A.D.; Tadiotto, G.; Russo, I.; Ferrazzi, B.; Tropea, S.; Buja, A.; et al. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Exposure in Melanoma Patients: A Retrospective Study on Prognosis and Histological Features. Environ. Health 2022, 21, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya Ozden, H.; Karadag, A.S. Could Endocrine Disruptors Be a New Player for Acne Pathogenesis? The Effect of Bisphenol A on the Formation and Severity of Acne Vulgaris: A Prospective, Case-controlled Study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3573–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, P.; Amouzgar–Hashemi, F.; Samsami, S.; Chinichian, S.; Oghabian, M.A. Aloe Vera for Prevention of Radiation-Induced Dermatitis: A Self-Controlled Clinical Trial. Curr. Oncol. 2013, 20, e345–e348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizza, L.; D’Agostino, A.; Girlando, A.; Puglia, C. Evaluation of the Effect of Topical Agents on Radiation-Induced Skin Disease by Reflectance Spectrophotometry. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2010, 62, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinta, F.; Ponzetti, A.; Spadi, R.; Fanchini, L.; Zanini, M.; Mecca, C.; Sonetto, C.; Ciuffreda, L.; Racca, P. Pilot Clinical Trial on the Efficacy of Prophylactic Use of Vitamin K1–Based Cream (Vigorskin) to Prevent Cetuximab-Induced Skin Rash in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Color. Cancer 2014, 13, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Danish Environmental Protection Agency Substances Under Evaluation for Endocrine Disruption Under an EU Legislation. Endocrine Disruptor List. List II. Available online: https://edlists.org/the-ed-lists/list-ii-substances-under-eu-investigation-endocrine-disruption (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Perréard, M.; Heutte, N.; Clarisse, B.; Humbert, M.; Leconte, A.; Géry, B.; Boisserie, T.; Dadoun, N.; Martin, L.; Blanchard, D.; et al. Head and Neck Cancer Patients under Radiotherapy Undergoing Skin Application of Hydrogel Dressing or Hyaluronic Acid: Results from a Prospective, Randomized Study. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Facial Area Symptoms | |

|---|---|

| Acne–papules–pustules–pimples | 14.29% |

| Couperus (red veins) | 23.81% |

| Erythema, redness | 38.10% |

| Hyperpigmentation, spots | 14.29% |

| Scars | 9.52% |

| Body Area Symptoms | |

|---|---|

| Itching/Itching | 11.25% |

| Dry skin | 20.00% |

| Scars | 13.75% |

| Redness | 18.75% |

| Pain | 8.75% |

| Skin sensitivity | 18.75% |

| Acne–papules–pustules–pimples | 1.25% |

| Hyperpigmentation–spots | 3.75% |

| Dyspigmentation–vitiligo | 2.50% |

| Small pimples | 1.25% |

| Hair Area Symptoms | |

|---|---|

| Hair loss (Alopecia) | 50.00% |

| Hair changes (color, texture) | 44.44% |

| Weakness | 5.56% |

| Number of Products Tested | Number of Patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facial Hygiene | Facial Hydration | Body Hygiene | Body Hydration | Hair Hygiene | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 1 | 5 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 9 |

| 0 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| No answer | 9 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 6 |

| Purchasing Channels | Number Patients |

|---|---|

| Pharmacy (pharmacy office or online platform) | 15 |

| Online websites of cosmetic products promoted as cosmetics for oncology patients | 2 |

| Dermatology Clinics—Aesthetic Medicine Clinics | 3 |

| Supermarkets | 10 |

| Herbalists | 4 |

| Drugstores | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Martín, M.-E.; Tarazona, J.V.; Hernández-Cano, N.; Mayor Ibarguren, A. The Importance of Cosmetics in Oncological Patients. Survey of Tolerance of Routine Cosmetic Care in Oncological Patients. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12040137

Fernández-Martín M-E, Tarazona JV, Hernández-Cano N, Mayor Ibarguren A. The Importance of Cosmetics in Oncological Patients. Survey of Tolerance of Routine Cosmetic Care in Oncological Patients. Cosmetics. 2025; 12(4):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12040137

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Martín, María-Elena, Jose V. Tarazona, Natalia Hernández-Cano, and Ander Mayor Ibarguren. 2025. "The Importance of Cosmetics in Oncological Patients. Survey of Tolerance of Routine Cosmetic Care in Oncological Patients" Cosmetics 12, no. 4: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12040137

APA StyleFernández-Martín, M.-E., Tarazona, J. V., Hernández-Cano, N., & Mayor Ibarguren, A. (2025). The Importance of Cosmetics in Oncological Patients. Survey of Tolerance of Routine Cosmetic Care in Oncological Patients. Cosmetics, 12(4), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12040137