Abstract

Hair loss is a widespread issue affecting both men and women, with significant aesthetic and psychological impacts. This study aimed to evaluate various hair restoration treatments, assess patient satisfaction, and identify the correlations between treatment types, treatment duration, and outcomes. We conducted a retrospective observational study on 50 patients who completed a 26-question online survey about their hair loss experience, treatments tried, and satisfaction levels. The treatments included FDA-approved drugs (finasteride and minoxidil), platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy, hormonal treatments, hair transplant surgery, and nutritional supplements. The results showed that a combination of PRP and topical minoxidil/finasteride produced significant improvements in hair density and thickness. Higher patient satisfaction was correlated with multiple treatment combinations and a longer treatment duration, while surgical hair transplants achieved the highest satisfaction rates despite their invasiveness. This study found that consistency and combination treatments are the key to the optimal hair restoration outcomes. Its limitations included a lack of racial diversity among the participants and the reliance on self-reported data. Overall, non-surgical therapies, particularly when combined, offer effective solutions for early-stage hair loss, while hair transplants remain the most definitive option for severe cases.

1. Introduction

Aesthetic treatments for different cosmetic problems have escalated in recent years. The desire to look younger for a longer period of time is now at hand for the majority of people, who can resort to minimal invasive procedures in order to maintain and even restore their youthful appearance. Aesthetic procedures are being used more frequently worldwide, and there is also an increasing demand for hair-restoring procedures, especially in men [1,2,3].

Apart from the aesthetic aspect, hair loss also causes major psychological distress among patients. Beyond cosmetic concerns, hair loss perpetuates a stress-mediated cycle, as this problem may generate stress, which in turn results in more hair loss. Apart from stress, there are also other factors involved in baldness—hormones, genetics, and environmental changes [4]. For example, elevated cortisol disrupts hyaluronan and proteoglycan synthesis in the skin, exacerbating follicular miniaturization [5].

The hair follicle follows the phases of a cycle—growth (anagen), regression (catagen), resting (telogen), shedding (exogen), and then growth again. These phases are determined by molecular signals which act in different pathways [6,7,8]. Androgenetic alopecia (AGA), the most common form of hair loss, involves the dihydrotestosterone (DHT)-mediated miniaturization of the follicles via 5α-reductase activation. Genetic polymorphisms in the α-reductase gene exacerbate follicular sensitivity to DHT, particularly in the frontal and vertex scalp regions. Variations in the androgen receptor gene are also critically involved in determining follicular sensitivity to DHT.

Evaluation of Hair Loss and Therapies for Hair Regeneration

Hair loss assessment ranges from invasive biopsies to advanced imaging. Histopathology remains definitive for diagnosing scarring alopecias but has largely been supplanted by non-invasive techniques. Trichoscopy identifies yellow dots (follicular hyperkeratosis) and perifollicular erythema, while phototrichograms quantify the anagen-to-telogen ratios through sequential imaging. Trichogram analysis, involving forceful hair extraction, determines pathologic telogen counts (>20%) compared to the normal ranges (6–13%). Laser scanning microscopy and hair weighing provide objective metrics, though dermoscopy suffices for a routine clinical evaluation [2,9].

Prior to a hair transplant, in cases of on-going hair loss where there are still thin follicles, patients are often prescribed medical therapies. Topical minoxidil (2% for women, 5% for men) enhances follicular vascularization via potassium channel activation, extending anagen duration [10]. Oral finasteride (1 mg/day) inhibits type II 5α-reductase, reducing serum dihydrotestosterone (DHT) to stabilize miniaturization. Adjuvant pharmacotherapies include latanoprost, a prostaglandin analog prolonging the anagen phase, and dutasteride, which suppresses >90% of DHT through the dual inhibition of 5α-reductase types I/II. Antiandrogens such as spironolactone, flutamide, bicalutamide, cyproterone acetate, and clascoterone antagonize the androgen receptors, particularly in female-pattern hair loss [11].

Regenerative approaches leverage platelet-rich plasma (PRP) centrifuged to concentrate growth factors (PDGF, VEGF) that reactivate the follicular stem cells [12,13,14,15]. Exosomes derived from the mesenchymal stem cells promoted the conversion from the telogen to the anagen phase in preclinical models [16,17]. Microneedling is also utilized for hair growth, with its the mechanism of action being improving vascularization and angiogenesis. In a study conducted by Dhurat et al., when comparing minoxidil with a combination of minoxidil plus microneedling, the latter treatment showed better results in terms of hair count [18].

Intradermal injections of botulinum toxin A mitigate DHT-induced ischemia by reducing scalp muscle tension [19]. Progenitor-cell-enriched micrografts offer a novel treatment for androgenetic alopecia. Harvested from the occipital region, they are processed using the Rigenera® device and injected into hair loss areas. The histological analysis by Ruiz et al. suggests they can generate new follicles, enhancing hair density [20].

Supplemental therapies include vitamin and mineral supplementation (such as vitamins C and D, folate, selenium, and iron), along with Nutrafol, Viviscal, caffeine, rosemary oil, pumpkin seed oil, and saw palmetto [10,21].

Surgical restoration via follicular unit transplantation (FUT) or extraction (FUE) offers definitive outcomes. FUE involves extracting individual follicular units from the occipital region, minimizing scarring. FUT entails removing an elliptical strip of scalp from the occipital area, dissecting the follicular units from the strip, and suturing the donor site before grafting the units to the recipient area [22,23].

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective observational study on a number of 50 patients experiencing hair loss treated during a two-year interval of time. The patient selection was performed based on 2 criteria—experience of hair loss which led to seeking professional help from a doctor and receipt of any type of hair treatment in the past.

The patients included in this study came from different doctors (dermatologists and plastic surgeons). The doctors contacted these patients and asked them to complete an online questionnaire with 26 questions related to their experience with hair loss. All patients who answered the questionnaire gave their consent to use the information they reported for scientific and research purposes in order to have the information analyzed, interpreted, and made public in specialty medical journals.

We inquired about the patients’ demographic information (sex, age), information about their hair (type, color), information about hair loss (period, localization, known cause and prior investigations, degree of hair loss prior to treatment, family history, and level of stress), information about the treatment (type and frequency, debut, and duration), and the results obtained after treatment (hair density, thickness, and degree of satisfaction with the treatment undergone).

Before-and-after photos of the patients who underwent treatment with PRP infiltration and topical foam with 0.5% finasteride and 5% minoxidil were taken in order to observe the clinical results of this treatment.

The patients who underwent surgical treatment—either FUE or FUT—were treated under local anesthesia, and follicle grafts were transplanted from the occipital region (which is not testosterone-influenced) to the fronto-parietal regions. In the case of FUE, special devices were used (such as an electric or manual follicle extractor or a Choi implanter). The surgical intervention has 2 steps—the first step is represented by the hair follicle extraction and hair follicle count. The second step is represented by implanting the extracted hair follicles.

To establish the correlation between the data provided in the questionnaire, IBM SPSS Statistics 26 was used. This questionnaire can be found in Annex 1.

3. Results

Results were obtained from the responses of 50 patients, each of whom answered a comprehensive 26-question survey regarding their experience with hair loss. The figures and tables below provide a detailed depiction of the data analysis and observed correlations. The results are exposed below as an epidemiological assessment, information about the patients’ disease status, clinical outcomes, and statistical findings.

3.1. The Epidemiological Assessment

In terms of the age distribution, 64% of the responders are between 31 and 40 years old, 18% between 41 and 50 years, and 14% 20 and 30 years old, with 54% of all of the responders being women. A total of 64% of the responders have straight hair, 30% wavy hair, and 6% curly, and none of the responders have coily hair. When referring to hair color, 52% have brown hair, 26% black hair, and 16% blond hair, followed by some cases of red and gray hair.

The correlation between sex and the area of hair loss was established as shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Correlation between hair loss area and sex.

Table 2.

Correlation between hair loss area and sex.

3.2. Information About the Patients’ Disease Status

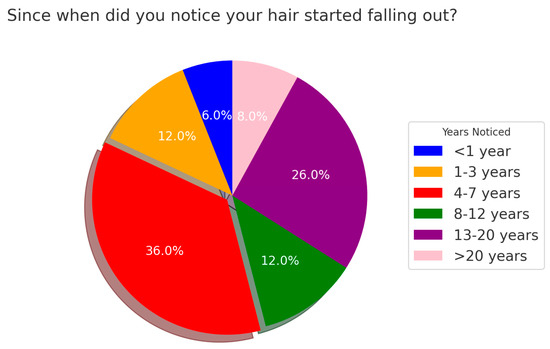

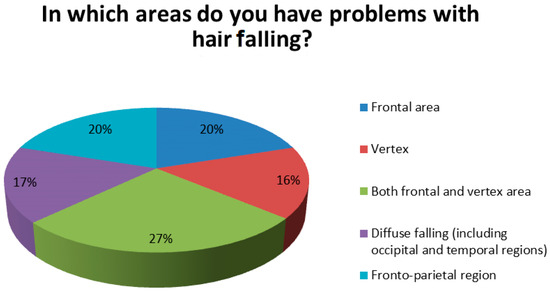

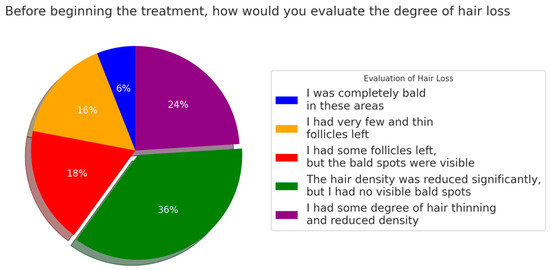

Information about the debut, areas, and degree of hair loss was provided as shown in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Debut of hair loss.

Figure 2.

Areas of hair loss.

Figure 3.

Degree of hair loss.

The information about pre-treatment investigations, as well as family history and degree of stress, reveals the following:

- –

- Most patients (80%) did not undergo trichoscopy prior to their first hair treatment.

- –

- Most patients (66%) had not had any investigations performed prior to treatment, while only 26% had had a blood analysis and 8% dermoscopy.

- –

- Most patients (68%) did not have any other medical condition associated with their hair loss, followed by 12% of cases being associated with endocrine disorders, 8% gynecological ones, and 6% psychological ones; one patient reported autoimmune diseases and one nutrition deficiency.

- –

- A total of 56% of the patients had a family history of alopecia.

The last two items of information received from the survey show that most of the patients did not have a medical diagnosis (rather, a genetic reason for hair loss), which indicates that these patients were treated for androgenetic alopecia.

Among the respondents, who rated their daily stress on a 1–5 scale, the majority (46%) reported a moderate stress level of 3.

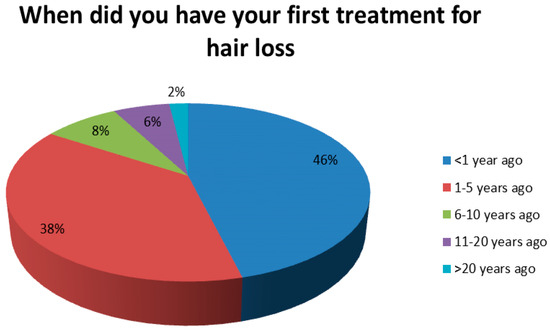

Figure 4.

Treatment debut.

Figure 5.

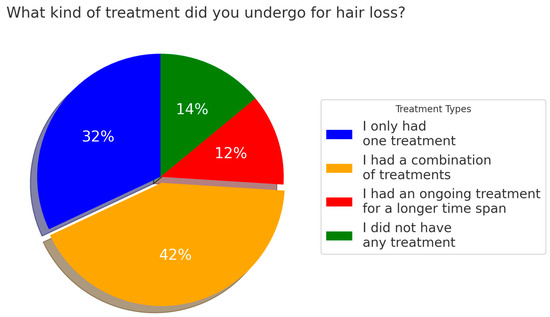

Type of treatment.

Among the surveyed group, a small proportion (12%) opted for hair transplant surgery, with FUE (10%) being more common than FUT (2%).

Overall, nearly half of the respondents (46%) reported experience with topical minoxidil, with the 5% concentration being slightly more common (26%) than the 2% concentration (20%).

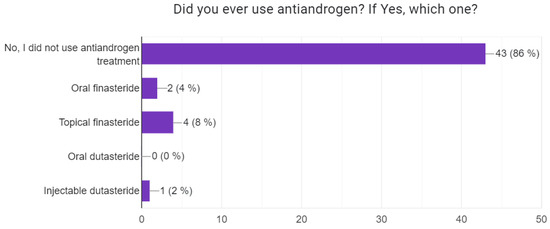

Concerning hormonal treatment (spironolactone, flutamide, bicalutamide, cyproterone acetate, and clascoterone), the majority of patients (96%) reported not using it. The use of antiandrogen treatment is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Antiandrogen treatment.

Regarding PRP (platelet-rich plasma), 66% of patients reported not using this method, while 22% indicated they had undergone 1–3 sessions, and 10% confirmed having 4–7 sessions. Concerning hormonal treatment, the majority of the patients (96%) reported not using it.

Concerning their supplement intake for hair growth, 62% of the participants took oral vitamins or minerals, while 30% reported no supplement use. Smaller percentages used caffeine (14%), rosemary oil (12%), Viviscal (2%), pumpkin seed oil (2%), and saw palmetto (2%). No participants reported using Nutrafol.

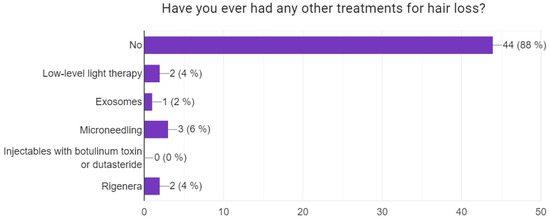

Figure 7 illustrates the additional therapies used for hair regeneration.

Figure 7.

Other therapies for hair regeneration.

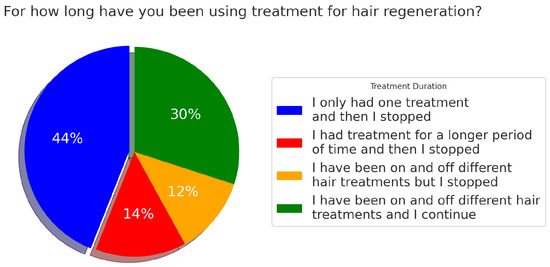

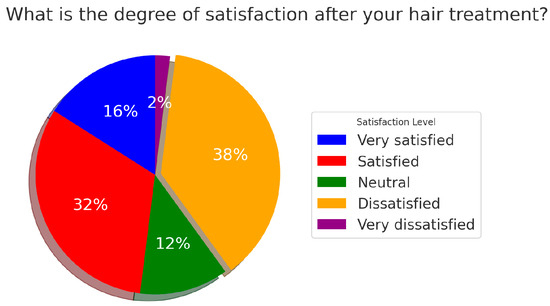

The final questions regarding the duration of the treatment and the degree of satisfaction are presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9. In a post-treatment assessment, 44% of the participants reported no change in their hair density, while 50% noted a moderate improvement and 6% observed a significant increase. Regarding hair follicle thickness, 46% experienced no change, 46% saw a moderate improvement, and 8% reported a significant increase.

Figure 8.

Duration of treatment.

Figure 9.

Degree of satisfaction.

3.3. Clinical Outcomes

The clinical results are based on a series of pre- and post-treatment images, which highlight visible improvements in hair density and thickness in patients treated with a combination of a topical mixture of finasteride and minoxidil with/without PRP infiltration (Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12). These images (Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12) depict enhanced scalp coverage, particularly in the frontal and vertex regions, where hair loss was initially prominent.

Figure 10.

Before and after 6 months with 5 × PRP and topical foam with minoxidil and finasteride.

Figure 11.

Before (hair transplant in other clinic) and after 3 months with 3 × PRP and topical foam with minoxidil and finasteride.

Figure 12.

Before and after 8 months with 4 × PRP and topical foam with minoxidil and finasteride.

3.4. Statistical Findings

The correlation between the hair transplant procedure and the degree of satisfaction was calculated, and the results are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlation between hair transplant procedure and degree of satisfaction.

The degree of satisfaction was also studied in correlation with the number of treatments for hair loss, and the results are presented in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

Correlation between the degree of satisfaction and number of treatments.

Table 5.

Chi-Square Tests.

Two other correlations between the duration of the treatment and hair density on the one hand and between treatment duration and hair thickness on the other hand were calculated. The results of these statistical analyses are presented in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 6.

Correlation between duration of treatment and hair density evolution.

Table 7.

Correlation between duration of treatment and hair thickness evolution.

4. Discussion

Hair loss constitutes a major aesthetic issue in both male and female patients. This study shows that the majority of the patients that consulted a physician to seek help for hair loss were young adults aged between 31 and 40, which might indicate that patients in this age group have a higher interest in improving, as well as the material resources to improve, their aesthetics. One supposition is that the younger generation may not experience this problem as much as those in this age group (or those who do might not have the financial support to pursue an expensive treatment for this problem).

In terms of the gender distribution, our study showed that both men and women were almost equally interested in solving the hair loss problem and resorted to medical treatments in order to improve their hair quality. However, while male baldness is generally accepted, societal pressures on women—where hair symbolizes femininity, health, and beauty—mean that female hair loss is often linked to greater emotional distress and psychological burden, including anxiety and depression [24].

When regarding hair type and color, most patients reported having straight hair, followed by having wavy hair and very few having curly hair, and no one responded as having coily hair. This result is due to the fact that the questionnaire was distributed mostly among Romanian patients who were Caucasian. The same explanation is available for hair color—most of the patients reported a brown or black color, which is characteristic of Caucasians.

In terms of the time interval since the patients had noticed their hair loss, most of the responders were in the 1–3-year interval group, followed by the 4–7-year group. This might indicate that patients seeking solutions for hair loss often do so soon after noticing the problem in its incipient stages. This is particularly useful as most non-surgical treatments rely on improving the shaft diameter of the existing hair follicles. The fact that most of the patients seeking medical treatment for hair loss are young adults (31–40 years old) suggests that this age group has both a heightened interest in aesthetics and the financial means to pursue these types of treatments.

Most of the patients who turned to hair scalp treatments answered that they presented a significant reduction in follicle density but without visible bald areas. This is also due to the fact that most of the patients identified the issue at an early stage, and therefore the clinical effect of the underlying problem was not yet visible.

When asked about the regions in which the patients had problems with hair falling out, both the frontal and vertex areas was the most frequent answer, followed by a diffuse pattern of hair falling (including the occipital and temporal regions). What was extremely important, however, in the correlation of the pattern of baldness with sex was the fact that almost all of the responders (11/12 patients) who claimed to have a diffuse hair falling pattern (including the occipital and temporal regions) were women.

Among women, diffuse hair loss is more frequent, while in men, the frontal and vertex areas are more often subject to hair loss (p = 0.015)—see Table 1 and Table 2.

A very small number of people had undergone an analysis prior to treatment, and even fewer patients had been investigated using a trichoscopy to evaluate the extent of their hair loss. This is due to the fact that there is no standardized protocol of investigation for this issue, and for this reason, underlying medical problems may be underdiagnosed. Therefore, there were relatively few patients whose hair loss problems were associated with a medical condition (mostly endocrine disorders, gynecological disorders, or psychological ones). Stress, which is an important factor in transient hair loss, was also incriminated for most patients.

Trichoscopy and basic blood analyses should be part of the routine investigation for hair loss. Certain vitamins (A–E) and minerals (Zn, Fe, Se) are essential for hair growth, and a lack of these nutrients may constitute a simple solvable cause of non-scarring alopecia [25,26].

In our study, genetic alopecia was present in almost half of the responders, who declared having a close blood relative suffering from alopecia. Furthermore, most of the responders had not previously been diagnosed with other medical conditions which could cause hair loss; for this reason, most of the responders were in the category of androgenic alopecia.

There are many factors which can cause alopecia, and a differential diagnosis between pathologic and idiopathic/androgenic alopecia should be considered.

A common autoimmune disease which also has a genetic component and causes non-scarring hair loss is alopecia aerata [27]. This affliction may vary from a single well-circumscribed patch to complete hair loss, including the eyebrows and eyelashes. In this case, the treatment includes several drugs, such as glucocorticosteroids, ciclosporin, azathioprine, methotrexate, tacrolimus, sulfasalazine, dapsone and mycophenolate mofetil; however, there is no consensus on the appropriate choice of treatment [28,29,30].

Alopecia areata is a pathology which may be linked to thyroid disease [31,32,33,34]. Autoimune pathologies (lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, celiac disease, vitiligo, and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) have been observed in patients with alopecia areata, with the most frequent association applying to the latter two (vitiligo and hypothyroidism) [35].

A systematic review on alopecia areata conducted by Fricke et al. showed an incidence of 2% worldwide, without a sex predominance. Furthermore, apart from the autoimmune diseases previously mentioned, these patients are also associated with psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and depression [36].

Another pathology which causes hair loss is represented by lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia. These afflictions cause primary scarring alopecia; their diagnosis through trichoscopy is suggested, but a biopsy is mandatory for diagnosis [37]. Although no treatment is effective for this pathology, antimalarials and oral steroids may slow the progression of this disease [38,39,40].

Vitamin D deficiency can also be a cause of hair loss, as it has been proven to play major roles in keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, as well as having immunomodulatory properties [41,42]. Not only is vitamin D deficiency associated with androgenic alopecia and telogen effluvium but it is also involved in alopecia areata, trichotillomania, and scarring alopecia.

In terms of the debut of the treatment for hair loss, a very high percentage had started therapy quite recently (<1 year), and more than 80% of the responders had initiated treatment in the past 5 years. This might be an indicator that hair therapies have grown more popular recently and that their efficiency might have spread their popularity among the general population.

When choosing the proper treatment for hair regeneration/restoration in androgenic alopecia, York et al. consider the optimal outcomes to be achieved when treatment is started in an early phase. Furthermore, the treatment plan, in their expert opinion, involves pharmacological options first (minoxidil, 5-alpha reductase inhibitors and prostaglandins), followed by PRP infiltration when patients are refractory to the initial treatment [43]. The same study shows that minoxidil and finasteride stop the progression of hair loss but can only partially regrow hair.

Hair transplants, according to our study, were recorded in a small number of patients, which indicates that surgical transplant is not as desired compared to less invasive procedures for hair loss. In these cases, the FUE technique, which is the least invasive of the two options, was the preferred treatment of choice. Both FUE and FUT are considered to be equally effective [44]. Only six patients had a hair transplant, but in terms of satisfaction, all of them reported a high degree of satisfaction after this procedure based on Table 3. In line with the findings of Maletic et al. (2024), our study confirms that hair transplantation significantly enhances patients’ quality of life, with high levels of post-procedural satisfaction reported among our cohort. This underscores the procedure’s substantial psychosocial benefits and its role in improving well-being for individuals experiencing hair loss [45].

The reason why a hair transplant was recorded in a rather small number in our questionnaire may be the fact that surgical treatment using FUE or FUT is considered not to be the first option but rather a back-up solution in cases of failure of medical treatment [46].

PRP is a therapy which was used in about one-third of the patients in our study. This is a minimally invasive procedure, but the infiltrations can be painful, even though it has been proven to have high efficacy. PRP stimulates the differentiation of stem cells, thus prolonging the anagen phase, as well as promoting angiogenesis and activating anti-apoptotic pathways, increasing the survival of dermal papilla fibroblasts [47]. The preparation of the PRP is also important and can lead to different results—Paichitrojjana conducted a study on 15 women with androgenetic alopecia in which he injected the right half of the scalp with double-spin-prepared PRP and the left half of the scalp with single-spin-prepared PRP. The results showed a higher hair density on the right half [48].

The clinical results shown in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 are a clear indicator that medical treatment with PRP or foam with minoxidil and finasteride can achieve good results through consistency and adherence to the specific treatment.

Topical minoxidil is one of the most frequently used therapies, which is also revealed from our study—almost half of the patients have undergone this therapy for hair loss. The reason this therapy is so popular is the fact that it is non-invasive and efficient and has few minor side-effects when administered orally (hypertrichosis, hypotension, and lower limb edema) [2]. Unlike minoxidil, surgical therapies and PRP infiltration also require asepsis measures in order to prevent infection. Clorhexidine is an efficient disinfectant which is used in scalp treatments because unlike betadine, chlorhexidine does not stain the treated area [49].

Hormonal treatment and antiandrogen therapies were not among the most used due to their possible side effects—erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, and ejaculation problems [2,50]. The other treatments included oral vitamins and minerals (31/50 patients), showing that most patients are more likely to try non-invasive procedures before going for more invasive and expensive treatments. However, only 11 patients had a blood analysis conducted to see whether they were lacking vitamins/minerals—the other 20 patients tried these supplements without knowing whether they had a deficit or not.

Other therapies (LLLT, exosomes, Botox, or Rigenera) are less frequently used, probably due to a lack of knowledge in both patients and physicians or due to financial considerations. Stem cell therapy has also contributed to hair regrowth in different manners—creating hair using tissue engineering, reversing the pathological mechanisms that cause hair loss, and the regeneration of hair follicles [51].

In our study, most of the patients underwent only one session/treatment and then stopped. This might explain the discrete results in some who said that they did not notice any change or only noticed a moderate improvement in density and thickness. In terms of satisfaction, most of the patients (38%) were neutral about the treatment, with answers of satisfied and highly satisfied accounting for 48% of the patients. Satisfaction based on the results might also have had a direct relationship with the treatment used (with the most highly satisfied patients being those who underwent a hair transplant).

We also analyzed the degree of satisfaction in the patients who tried one, two, or three different treatments. The results showed that the higher the number of treatments undergone, the higher the satisfaction with the results (Table 4 and Table 5). The idea of combining treatments has been proven to have synergistic effects, with PRP in combination with microneedling and laser therapy achieving better results in dermatology than individual treatments [52].

The correlation between hair density and the duration of treatment showed that most patients (25 patients—50%) presented a moderate improvement in hair density, with the highest percentage being in the group that pursued several treatments and continued with them (12 patients).

When correlating the duration of treatment with an improvement in hair thickness, most of the interviewed patients (23 patients—46%) presented a moderate improvement in hair thickness, with the highest percentage among the patients having tried out different hair treatments and then having continued treatment (13 patients—26%). This analysis also had statistical power (p < 0.001).

The limitations of this article are the lack of variety in the ethnicity and race of the patients, as well as the small number of patients included in this study. Another shortcoming of this study is the subjective evaluation both before and after treatment carried out by the patients and the lack of an evaluation by the physicians treating the patients.

5. Conclusions

Hair loss affects both men and women equally. Progress in technology has shown that nowadays there are a variety of options available. Androgenic alopecia seems to be the main cause of hair loss, and different therapies are available for it.

Trichoscopy should be recognized as an essential component of a thorough dermatological examination, even though it is still underutilized.

PRP infiltration and minoxidil with/without finasteride have proven useful in hair regeneration but require continuity in treatment. Hair transplants remain the fastest option for hair loss, with a high degree of satisfaction, but they are quite invasive and not suitable for all patients.

Moreover, the best results are achieved through a combination of treatments, which effectively prevents further hair loss and highlights the importance of adherence to the treatment plan.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.M., C.G. and S.A.M.; Methodology: A.M., M.-Ș.T., S.-E.B., A.V.D. and D.A.Ț.; Software: A.M.C.; Validation: C.G. and A.M.; Formal analysis: S.-E.B.; Investigation: A.M.; Resources: S.-E.B. and A.M.; Writing—original draft preparation: A.M.; Writing—review and editing: M.-R.C., D.Ș., S.A.M. and C.G.; Supervision: S.A.M. and C.G.; Funding acquisition: C.G. and S.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the St. John’s Hospital’s Ethics Committee (registration number 10180/24.05.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all of the subjects involved in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Thomas, J.R. Techniques for Hair Restoration. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 28, ix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, A.; Băloi, S.-E.; Ion, D.; Andrei, C.-L.; Marinescu, S.A.; Dragomiroiu, G.T.A.B.; Giuglea, C. Clinical assessment of the therapeutic options for alopecia treatment. Farmacia 2021, 69, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehan, J.N.; Spiegel, J.H. Hair Restoration Techniques. Facial Plast. Surg. 2023, 39, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, P.M.; Miot, H.A. Female Pattern Hair Loss: A clinical and pathophysiological review. Bras. Dermatol. 2015, 90, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thom, E. Stress and the Hair Growth Cycle: Cortisol-Induced Hair Growth Disruption. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2016, 15, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stenn, K.S.; Paus, R. Controls of hair follicle cycling. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 449–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semalty, A.; Semalty, M.; Joshi, G.P.; Rawat, M.S. Techniques for the discovery and evaluation of drugs against alopecia. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2011, 6, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semalty, M.; Semalty, A.; Joshi, G.P.; Rawat, M.S. Hair growth and rejuvenation: An overview. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2011, 22, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, L.C. Atlas of Hair Pathology; The Parthenon Publishing Group: Nashville, TN, USA, 2003; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Suchonwanit, P.; Thammarucha, S.; Leerunyakul, K. Minoxidil and its use in hair disorders: A review. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2019, 13, 2777–2786, Erratum in Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2020, 14, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Devjani, S.; Ezemma, O.; Kelley, K.J.; Stratton, E.; Senna, M. Androgenetic Alopecia: Therapy Update. Drugs 2023, 83, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, A.; Savescu, M.; Marin, G.G.; Dricu, A.; Parasca, S.; Giuglea, C. Evaluation of muscle atrophy after sciatic nerve defect repair—Experimental model. Rom. J. Mil. Med. 2022, 125, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trambitas, C.; Pap, T.; Niculescu, R.; Popelea, M.C.; Cotoi, O.S.; Cordoș, B.; Domnariu, H.-P.; Marin, A.; Feier, A.M.; David, C.; et al. Biocompatible 3D-Printed Devices with Adipose Stem Cells in the Regenerative Process of Sciatic Nerve Lesions in Rodent Models: An Experimental Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e62412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, C.S.; Smith, P.A. Clinical Update: Why PRP Should Be Your First Choice for Injection Therapy in Treating Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2018, 11, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mlynarek, R.A.; Kuhn, A.W.; Bedi, A. Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) in Orthopedic Sports Medicine. Am. J. Orthop. 2016, 45, 290–326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nestor, M.S.; Ablon, G.; Gade, A.; Han, H.; Fischer, D.L. Treatment options for androgenetic alopecia: Efficacy, side effects, compliance, financial considerations, and ethics. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3759–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, H.; Jing, J.; Yu, L.; Wu, X.; Lu, Z. Regulation of hair follicle development by exosomes derived from dermal papilla cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 500, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhurat, R.; Sukesh, M.; Avhad, G.; Dandale, A.; Pal, A.; Pund, P. A randomized evaluator blinded study of effect of microneedling in androgenetic alopecia: A pilot study. Int. J. Trichology 2013, 5, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, A.; Bălăceanu, L.-A.; Marinescu, S.-A.; Burcea-Dragomiroiu, G.-T.-A.; Dîdă, M.-A.; Mirică, A.; Giuglea, C. A double perspective on botulinum toxin in Romania used for aesthetic clinical applications. Farmacia 2024, 72, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, R.G.; Rosell, J.M.C.; Ceccarelli, G.; De Sio, C.; De Angelis, G.C.; Pinto, H.; Astarita, C.; Graziano, A. Progenitor-cell-enriched micrografts as a novel option for the management of androgenetic alopecia. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 4587–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Jeong, D.W.; Choi, E.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.G.; Yi, Y.H.; Cha, H.S. Effect of pumpkin seed oil on hair growth in men with androgenetic alopecia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 549721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, N.E. Hair transplantation update. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2015, 34, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Ranjan, A. Follicular Unit Extraction (FUE) Hair Transplant: Curves Ahead. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2019, 18, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mohamed, N.E.; Soltan, M.R.; Galal, S.A.; El Sayed, H.S.; Hassan, H.M.; Khatery, B.H. Female Pattern Hair Loss and Negative Psychological Impact: Possible Role of Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2023, 13, e2023139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudnicka, L.; Olszewska, M.; Waśkiel, A.; Rakowska, A. Trichoscopy in Hair Shaft Disorders. Dermatol. Clin. 2018, 36, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almohanna, H.M.; Ahmed, A.A.; Tsatalis, J.P.; Tosti, A. The Role of Vitamins and Minerals in Hair Loss: A Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 9, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perera, E.; Yip, L.; Sinclair, R. Alopecia areata. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 2015, 47, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J. Alopecia Areata: An Update on Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 61, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterkens, A.; Lambert, J.; Bervoets, A. Alopecia areata: A review on diagnosis, immunological etiopathogenesis and treatment options. Clin. Exp. Med. 2021, 21, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranwell, W.C.; Lai, V.W.Y.; Photiou, L.; Meah, N.; Wall, D.; Rathnayake, D.; Joseph, S.; Chitreddy, V.; Gunatheesan, S.; Sindhu, K.; et al. Treatment of alopecia areata: An Australian expert consensus statement. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2019, 60, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandrini, A.; Starace, M.; Bruni, F.; Brandi, N.; Baraldi, C.; Misciali, C.; Fanti, P.A.; Piraccini, B.M. Alopecia areata incognita and diffuse alopecia areata: Clinical, trichoscopic, histopathological, and therapeutic features of a 5-year study. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2019, 9, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asz-Sigall, D.; González-De-Cossio-Hernández, A.C.; Rodríguez-Lobato, E.; Ortega-Springall, M.F.; Vega-Memije, M.E.; Guzmán, R.A. Differential diagnosis of female-pattern hair loss. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2016, 2, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciongariu, A.M.; Țăpoi, D.A.; Dumitru, A.V.; Bejenariu, A.; Marin, A.; Costache, M. Pleomorphic Liposarcoma Unraveled: Investigating Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Markers for Tailored Diagnosis and Therapeutic Innovations. Medicina 2024, 60, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, A.J.; Schwartz, R.A.; Janniger, C.K. Alopecia areata. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2000, 1, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, P.P.; Farrukh, S.N. Association between alopecia areata and thyroid dysfunction. Postgrad. Med. 2021, 133, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasante Fricke, A.C.; Miteva, M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: A systematic review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 8, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fechine, C.O.C.; Valente, N.Y.S.; Romiti, R. Lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia: Review and update of diagnostic and therapeutic features. Bras. Dermatol. 2022, 97, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossard, S.; Lee, M.S.; Wilkinson, B. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: A frontal variant of lichen planopilaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1997, 36, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuglea, C.; Burlacu, E.C.; Dumitrache, S.; Tene, M.G.; Marin, A.; Jianu, D.M.; Marinescu, S.A. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy in Postbariatric Lower Body Lift—A Method of Decreasing Postoperative Complications. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2022, 46, 2882–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baibergenova, A.; Donovan, J. Lichen planopilaris: Update on pathogenesis and treatment. Skinmed 2013, 11, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bertoli, M.J.; Sadoughifar, R.; Schwartz, R.A.; Lotti, T.M.; Janniger, C.K. Female pattern hair loss: A comprehensive review. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, K.; Mysore, V. Role of vitamin D in hair loss: A short review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3407–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- York, K.; Meah, N.; Bhoyrul, B.; Sinclair, R. A review of the treatment of male pattern hair loss. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2020, 21, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Love, R.P.; Harris, J.A. Old Friend or New Ally: A Comparison of Follicular Unit Transplantation and Follicular Unit Excision Methods in Hair Transplantation. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maletic, A.; Dumic-Cule, I.; Zic, R.; Milosevic, M. Impact of Hair Transplantation on Quality of Life. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2024, 48, 1825–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varothai, S.; Bergfeld, W.F. Androgenetic alopecia: An evidence-based treatment update. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2014, 15, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emer, J. Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP): Current Applications in Dermatology. Ski. Ther. Lett. 2019, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Paichitrojjana, A.; Paichitrojjana, A. Platelet Rich Plasma and Its Use in Hair Regrowth: A Review. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2022, 16, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianu, D.M.; Marin, A. Invited Discussion on: Evaluation of Chlorhexidine Concentration on the Skin After Preoperative Surgical Site Preparation in Breast Surgery-A Randomized Controlled Trial. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2022, 46, 1523–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysore, V.; Shashikumar, B.M. Guidelines on the use of finasteride in androgenetic alopecia. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2016, 82, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, P.; Garcovich, S. Advances in Regenerative Stem Cell Therapy in Androgenic Alopecia and Hair Loss: Wnt pathway, Growth-Factor, and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Signaling Impact Analysis on Cell Growth and Hair Follicle Development. Cells 2019, 8, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, R.S., Jr.; Ruiz, S.; DoAmaral, P. Microneedling and Its Use in Hair Loss Disorders: A Systematic Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).