Abstract

Nowadays, the flourishing development of modern cosmetics, and of “green cosmetics” especially, leads to rapid product innovation, with the increasing use of novel natural ingredients from unusual sources. A peculiar group of slime molds that have long been controversially classified as plants, fungi, or animals represents such an uncommon resource. In this regard, it is strange that these fascinating low-eukaryotic organisms are conspicuously absent from the current reviews of natural cosmetic sources and have no industrial cosmetics utilization. Chemical analyses have confirmed that the slime molds produce a plethora of novel or rare secondary metabolites of interest for cosmetics (127 substances), many of which exhibit biological activity. Interestingly, novel compounds were isolated from 72% of the 53 checked species. At the same time, the number of studied species, from a total of more than 900 currently recognized, is strikingly low (0.06). Such great unexplored biodiversity leaves a space wide open for new discoveries, presenting the slime molds as a reservoir of new biologically active substances that may provide valuable natural ingredients (pigments, lipids, aromatic substances, etc.) for application in modern cosmetics. Therefore, the current review aims to provoke a stronger interest in this neglected aspect, outlining the knowledge that has been obtained so far and indicating some challenges and perspectives for the future.

1. Introduction

Since ancient times, natural products have been utilized by people in traditional medicine and daily life; however, nowadays, there is a notably increasing recognition of their high scientific and industrial value [1,2] with a growing demand for natural versus synthetic ingredients. Moreover, the trend for the creation and use of so-called “green cosmetics” is on the rise [3]. The demand for green cosmetics means the industry is looking for natural materials and additives for skin- and haircare products and also toiletry preparations [4]. At the same time, the growing environmental and health awareness of society requests the applied natural products to be safe, non-toxic, eco-friendly, efficient, and low-cost [3,5]. Thus, the present situation stimulates the search and application of products that come from unusual types of organisms or from organisms growing in very specific, sometimes extremophilic, habitats and conditions [5,6]. In this regard, it is strange that these peculiar slime molds, which long have been grouped with fungi but, in fact, “are neither plants, nor animals, nor fungi” [7], are conspicuously absent from the current reviews of natural cosmetic sources and have no industrial cosmetics application.

In nature, these fascinating organisms have been observed by people for as long as mankind has existed [7]. Their biology has attracted scientists for more than 300 years [8,9], and they have been investigated as valuable model organisms for studying eukaryotic cell functions [10], genetic, cellular, and biochemical processes [11], including cell communication and differentiation, apoptosis (programmed cell death), the evolution of cooperation and social behavior [12], and for problem-solving in aneural biological systems [13]. Currently, the integrative transdisciplinary potential of the application of myxomycetes in the field of STEM (a popular abbreviation for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) [14] and also in the arts, communication, and public policy has been noted [9].

Slime molds in the vegetative stage of their life cycle occur as heterotrophic, multinuclear, acellular (syncytial) cytoplasmic structures devoid of cell walls, named plasmodium or pseudoplasmodium (also named slug in its initial stage) in the case of cellular aggregations [15]. With regard to their most striking peculiarity, the ability of plasmodia for active, creeping movement by cytoplasmic streaming, slime molds have long been controversially classified as plants, fungi, and animals (for details, see [8,9,16,17]). Although the taxonomical, nomenclatural, and classification aspects are beyond the scope of this review, for the better orientation of the reader, we have to note that modern genetics has proven the separate monophyletic position of slime molds in the protozoan super class Amoebozoa, where they are classified according to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature [18]. Despite this formal classification, for practical reasons, these low-eukaryotic organisms have been and, most probably, will continue to be studied by mycologists. Therefore, the classification of species has been and, most likely, will continue to be based on The International Code of the Nomenclature of Algae, Plants and Fungi, formerly named the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature [19] (for details, see [20,21]).

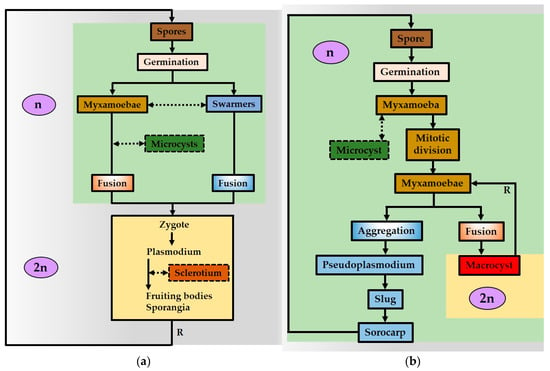

In the current paper, the broad term “slime molds” is used due to its common acceptance and practical applicability as comprising of organisms, the life cycle of which is represented by a plasmodial/pseudoplasmodial vegetative stage that regularly alters an immobile reproductive stage (Figure 1). The last comprises of fruiting bodies that produce spores. In cellular slime molds, the spores derive only amoeboidal cells that can move by cytoplasm strands and forage for bacteria or other simple life forms (Figure 1b), while acellular slime molds spores, depending on the water availability in the environment, develop either as amoeboidal cells (myxamoebae) or as motile swarmers (myxoflagellates) without cell walls, which bear two flagella [7,16,19,20,21,22,23] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Life cycle of acellular (true) slime molds; (b) life cycle of cellular slime molds.

The unique particularity of most acellular slime molds is the ability of swarmers to lose their flagella and to transform into myxamoebae when lacking free water or, vice versa, the ability of amoeboids to transform into swarmers when water is available [16,24]. In addition, in unfavorable conditions (high temperatures, drought, food depletion, etc.), each myxamoeba can encyst in a resting cell, named microcyst. This happens by assuming a round shape and forming a cell wall. When living conditions improve, microcysts become active cells again. Both swarmers and myxamoebae behave like sexual cells and, by fusing, form a zygote that produces the next vegetative stage through multiple divisions [20,21,22,23]. In unfavorable conditions, the plasmodium can also dehydrate and harden, encysting in a specific resting stage, surrounded by a polysaccharide cell wall, named sclerotium [20,24,25] (Figure 1). The pseudoplasmodium can produce a similar dormant stage, surrounded by a cell wall that is commonly known as a macrocyst [23,24] (Figure 2b). In proper conditions, the dormant sclerotium, or microcyst, develops respectively in plasmodia or pseudoplasmodia that produce fruiting bodies [24,25] (Figure 1). In addition to such sexual cycles, plasmodia may fragment but may well fuse, and therefore, it is possible for several colonies found in different places to constitute a clone, being genetically identical to each other [26].

Figure 2.

Plasmodia and fruiting bodies of one species from Protosteliomycetes and three Myxomycetes: (a) white plasmodium of the protostelid Ceratomyxa cf. fruticulosa in the process of transformation into fruiting bodies; (b) magnified part of the same plasmodium with initial fruiting bodies; (c) yellow plasmodium of Fuligo septica in the process of transformation into fruiting bodies; (d) magnified developed plasmodium of F. septica with the whitish remnants of the early plasmodial stage; (e) dark brown clusters of sporangia of Stemonitis splendends Rostaf. on a bark of a decaying tree; (f) magnified cluster of S. splendens sporangia on the same tree, in which each thread-like separate sporangium is visible; (g) magnified clusters of S. splendens sporangia on the same tree with the visible shining basis of the sporangia; (h) magnified part of the same sporangial group with a knife pointing out the shining basis of the sporangia, responsible for the species epithet “splendens”; (i) up: pinkish-red large and small plasmodia of Lycogala epidendrum on decaying tree bark; down: magnified L. epidendrum aethalia; (j) general view of aethalia of Lycogala epidendrum at different stages of development (young aethalia are pink, matured aethalia are violet-brownish) (Photos: M. P. Stoyneva-Gärtner).

Slime molds demonstrate high evolutionary success [27] and have a higher within-group genetic divergence than other organisms such as vascular plants, higher animals, or true fungi [21]. During their long-lasting development from ancient times until now, slime molds have managed to inhabit various habitats. Most of them are free-living terrestrials, occurring predominantly in the moist conditions of forest ecosystems in soils and on tree barks or leaves, and a few are aquatic [7]. Doubtless, the physiological and ecological peculiarities of these strongly adaptive organisms are closely related to their biochemical composition. Although the first antibiotic compound was reported about eight decades ago [28,29], it received surprisingly little attention from the scientific community. The first review of the secondary metabolites of slime molds [30] outlined some unique substances and stimulated further studies that demonstrated that part of the compounds displayed various bioactivity, such as antibacterial (with a stronger suppression of Gram-positive than Gram-negative bacteria), antitumor, cytotoxic and antioxidant activities [7,10,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Some of these biologically active compounds have been taken as promising sources of new drugs, such as: (i) physarin (physarine) for hemagglutinins; (ii) arcyriaflavin C, makaluvamine A, cycloanthranilyloproline (fuligocandin B), etc. for anticancer treatment; (iii) 3,4-dixodroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) against Parkinson’s disease or furanodictines A and B against other neurological diseases (for details, see [7,38,39]). Nevertheless, the number of checked species is quite small so far [6,29].

Up to now, most of the secondary metabolites have been extracted directly from the fruiting bodies of slime molds, and this fact has stimulated their in vitro cultivation [29]. The most successful cultivation was achieved for the species from the genera Physarum and Didymium [29]. The vegetative plasmodium (or pseudoplasmodium) of quite a few species has been successfully cultivated on a practical scale [32]. In fact, the biochemical composition of these strange creatures remains relatively unknown, and it could be supposed that it may comprise a much greater plethora of unusual compounds with unique chemical structures. The great biodiversity of slime molds, with more than 900 species currently recognized [27], leaves a space wide open for new discoveries, presenting them as an untapped reservoir for new active substances that may provide valuable natural sources for utilization in modern cosmetics. Therefore, the current review aims to provoke a stronger interest in this neglected area, outlining the knowledge that has been obtained so far.

2. Materials and Methods

In the review, the terms “cosmetics” and “cosmetics industry” are used in their broadest sense, which includes the combined term “cosmeceutics/cosmeceutical” that comes from the merging of cosmetics and pharmaceuticals and also the term “cosmotherapy”, coined for therapeutically efficacious cosmetics [5,40,41,42].

The review is based on a search in acknowledged scientific bases (Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, etc.) with the use of relevant keywords (slime molds, myxomycetes, cosmetics, natural compounds, lipids, terpenes, etc.) and on a search in our private library archives. The names, structures, and formulas of chemical compounds have been checked in the PubChem database of the National Center for Biotechnological Information (NCBI; Bethesda, MD, USA) [43], along with the Latin names and classification sources in the NCBI Taxonomy Browser [44]. The Latin names of slime molds follow The International Code of the Nomenclature of Algae, Plants and Fungi [19] and have been checked for current synonyms in the database Index Fungorum [45], which reflects the newest relevant taxonomical, nomenclatural, and classification changes.

In this review, we accept that slime molds are comprised of three groups that, according to [20], form three classes in the phylum Eumycetozoa, as follows: (i) Myxomycetes (Myxogastrea, myxogastrids, acellular slime molds, true slime molds)—free-living organisms with acellular multinucleate creeping heterotrophic plasmodium devoid of cell walls and with a complex structure of macroscopic fruiting bodies (Figure 2); (ii) Dictyosteliomycetes (Dictostelea, dictyostelids, cellular slime molds, or social amoebae)—free-living organisms that have pseudoplasmodium (literally “false plasmodium”) formed by the aggregation of numerous uninucleate naked amoebae, and (iii) Ceratiomyxomycetes (Ceratiomyxea, protostelids)—the small plasmodia of which are lacking regular shuttle streaming, and which have very small fruiting bodies that produce one to a few spores (Figure 2).

The following division of the types of fruiting bodies (also known as fruit bodies, fruitbodies, or fructifications) that are producing spores has been accepted after [7,16,21,24]: (i) sporophore or myxocarp—for all singular spore-bearing structures, mainly of acellular slime molds, as a broad term that also embraces the terms sporocarp and sporangium (pl. sporangia), used also for other organisms (Figure 2); (ii) sorus (pl. sori)—for a cluster of sporangia; (iii) aethalium (pl. aethalia)—for a large, visible-with-the-naked-eye, cushion-shaped fruiting body of certain acellular slime molds that is formed by the aggregation of many merged sporangia at the early stages of their development (Figure 2); (iv) pseudoaethalium (pl. pseudoaethalia), or the “false aethalium” of acellular slime molds—a common single structure formed from a closely clustered group of distinct sporangia; (v) plasmodiocarp—for a sessile, flattened fruiting body that covers the veins of the plasmodium from which it was derived, in this way maintaining the initial shape of the plasmodium; (vi) sorocarp—a specific term for the fruiting body of the cellular (dictyostelid) slime molds, which is formed from the pseudoplasmodium and consists of a special stalk, named sorophore (mostly cellular and rarely acellular), and a cluster of sporangia that form a common sorus with numerous spores.

3. Results

In the text below, we discuss only those selected natural secondary metabolites that, according to the current knowledge and our expertise, can be successfully used in modern cosmetics due to their indicated antibiological (mostly antibacterial), anti-inflammatory or anticancer abilities, in addition to their other functional properties.

3.1. Pigments

In nature, slime molds are fascinating for their bright colors, with the predominance of red, orange, and yellow tints based on a palette of pigments discovered as natural colorants of both plasmodia and fruiting bodies. In this regard, the pigments of slime molds, most of which are unique in their chemical structure, are of special interest for cosmetic products, in which color is one of the key factors [3]. Pigments are widely recognized among the most-used coloring agents in cosmetic formulations, starting from nail polishes and lipsticks to personal care items such as soap [46]. Some of these products (nail colorants, eyelashes, cremes, rouge, body lotions) can be applied for a longer time, but some (soap, shampoo, gel) are removable shortly after use [3,47]. In addition, many pigments are known for their photoprotective role against strong insolation and ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which makes them valuable constituents of sunscreen and skincare products [5].

3.1.1. Plasmodial Pigments

Due to the widely diverse pigmentation of plasmodia, various authors have suggested the quite-different chemical characteristics of pigments (i.e., pteridines, polyenes, peptide-containing pigments, or phenolic compounds) even in the same species [48]. Starting from early explorative studies until now, it has been demonstrated that these pigments strongly absorb the light from the UV–visible spectra, have remarkable antibiological and cytotoxic activity, and also chelate metals, providing strong defense to the vulnerable in natural plasmodia [29,30,31].

In 1948 [28], the authors practically isolated the first slime mold pigment from the yellow plasmodium of the acellular slime mold Fuligo septica (Figure 2b), commonly known as scrambled egg slime, flowers of tan, or the dog vomit slime mold [49]. Later, this pigment had two anthraquinone acids as its derivates after its first “host” was named fuligorubin A (for details, see [30])-Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical compounds, isolated from slime molds, organized in a taxonomical order by classes and the alphabetical order of species in the classes.

Only forty years later, fuligorubin A proved to be the first tetramic acid derivative isolated from slime molds, C20H23NO5 [43,72], and was successfully synthesized [117]. It is thought to be involved in photoreception and in the process of energy conversion during its life cycle [48]. Subsequently, similar pigments with a butenolide structure, acyltetramic acids, were isolated from the orange-yellow plasmodia of the acellular Leocarpus fragilis [30].

A decade later, two unusual tetramic acids, viz., polycephalins B and C, together with the yellow optically-active physarorubinic acids A (C180H19NO6 [43]) and B, were isolated and synthesized from the plasmodium of Physarum polycephalum (commonly known as “the blob” [118]) [90,91,92]. Other novel yellow plasmodial pigments isolated from the same species were: (1) chrysophysarin A (C21H30N3O2 [43]) [93]; (2) physarochrome A, a unique combination of L-glutamine with a penta-unsaturated carboxylic acid carrying a 2-acetylamino-3-hydroxyphenyl end group [86].

The naphthoquinone red pigments lindbladione and lindbladiapyrone were isolated as salts from the acellular plasmodia of Lindbladia tubulina [30,75]. Lindbladione, a hexaketide [119], is a neural stem-cell differentiation activator that also inhibits the dimerization of the specific protein Hes1 (hairy and enhancer of split-1), has been successfully synthesized [76]. Another specific natural pigment with a pyrone ring connected with a long aliphatic side-chain, ceratiopyrone (ceratiopyron A, C21H30O3 [43]), was found in the diploid plasmodia of the widespread protostelid slime mold Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa [30,50] (Figure 2). Another unusual amide derivative with a pyrone ring, fuligopyrone (C18H17NO5 [43]), was discovered in the plasmodia of Fuligo septica [30].

Melanin (C18H10N2O4 [43]), a natural pigment found in different organisms, is commonly considered protective against harmful environmental factors, such as high doses of UV radiation or oxidative stress [25,120,121]. Therefore, the ability to produce this polymer seems to possess adaptative values [122]. In vegetative plasmodia, the ability to produce melanin has been demonstrated so far only in the acellular slime mold Physarum nudum and only in response to irradiation with white light [25,89]. In earlier studies, it was shown that the plasmodia of Physarum nudum and Physarum polycephalum produced complexes of non-heme iron with nitric oxide, and when cultivated in liquid cultures with haemin in the medium, they additionally produced nitrosylheme complexes [123]. Instead of melanin, the dark acellular plasmodia of Metatrichia vesparium had high amounts of manganese [124].

3.1.2. Pigments of Dormant Sclerotia

Fuligo septica usually has yellow plasmodia (sometimes with a brown tint in the old mucosal veins) and commonly forms yellow dormant sclerotia, but sometimes, it may produce dark brown or even black sclerotia that contain melanin [25]. Interestingly, the color is related to the viability of sclerotia: 60% of the yellow sclerotia with the lowest content of melanin are able to reproduce, whereas, on the contrary, 100% of the dark sclerotia never form viable plasmodia [25]. In this case, it was supposed that the melanization was not protective, despite the fact that the protective role of melanin has been commonly accepted [122].

3.1.3. Pigments of Fruiting Bodies

Some of the pigments of fruiting bodies belong to the large natural group of carbazole alkaloids (bisindoles), derivatives from the oxidative dimerization of tryptophan, which are of current interest mainly because many of them are potent anticancer agents [125]. This broad group includes indolocarbazoles—heterocyclic compounds with a carbazole core fused to an indole system through its nitrogen-containing ring—which are known to derive from L-tryptophan by a four-enzyme pathway [125,126]. The interest in them and their artificial synthesis stems from their antibiotic properties [124]. Other natural pigments are lactones, secondary metabolites formed by cyclic carboxylic esters, important for dermal cosmetics due to their considerable biological activity expressed by general antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor properties [127,128,129].

One of the first studied species regarding the pigments of fruiting bodies was the acellular Arcyria denundata, from the red sporophores of which a series of alkaloid-like pigments, including the rare bisindoles, were isolated: arcyriacyanin A (C20H11N3O2 [43]), dihydroarcyrioxocin A, arcyroxocins A (C20H11N3O3 [43]) and B (C20H11N3O3 [43]), arcyroxindole A, arcyriarubins A, B (C20H13N3O6 [43]), and C (C20H13N3O4 [43]), arcyriaflavins A (C20H11N3O2 [43]), B (C20H11N3O3 [43]) and C (C20H11N3O4 [43]), and arcyrioxepins A-B, along with a novel bisindole sulfate, i.e., arcyriarubin B 6-O-sulfate (C20H13N3O6S [43]) [30,56,58]. The successful synthesis of arcyroxocins A and B was reported [57]. All these pigments were determined to be responsible for the red and yellow colors of the fruiting bodies, but they also demonstrated different levels of antibacterial activity against Bacillus brevis and Bacillus subtilis [30,31,56]. Moreover, they are lead structures for diverse biologically active compounds and exhibit different anticancer properties due to strong cytotoxicity [31,52]. According to the PubChem database [43], arcyroxocin A was found in the protostelid genus Ceratiomyxa, but this is questionable since, in the provided reference of Steglich [30], such information cannot be found.

Arcyriarubin A was also found in the wild fruiting bodies of another species of the genus Arcyria, Arcyria obvelata, from which the novel dihydroarcyriacyanin A (C20H13N3O2 [43]) was obtained and characterized [58]. According to the PubChem database [43], the same species contains arcyriaflavins A-C. Arcyriaflavin B was also discovered in Ophiotheca chrysosperma (Syn. Perichaena chrysosperma) [53]. Arcyriaflavin A has been attributed, without a source, to the same species in [43].

The bisindoles arcyriarubin C (C20H13N3O4 [43]) and arcyriaflavin C were also found in the red sporophores of Arcyria ferruginea, from which the novel bisindole alkaloid dihydroarcyriarubin C was determined [31,52,59]. According to the conducted experiments, arcyriaflavin C was cytotoxic [59]. In a further study of the biologically active compounds from this myxomycete, cis-dihydroarcyriarubin C showed a moderate inhibition of the Wnt signal transcription [60].

In the yellow sporophores of Arcyria obvelata (Syn. A. nutans (Bull.) Grev.), besides arcyriaflavins A and B, two colorless dihydro derivatives of arcyriacyanin A and arcyrioxocin A were found [30].

Arcyriaflavins B and C were also isolated from the pseudoaethalia of the acellular slime mold Siphoptychium casparyi (Syn. Tubifera casparyi [130]) [59]. Only arcyriaflavin C was found in Metatrichia vesparia [84]. Two novel cytotoxic bisindoles, i.e., 5,6-dihydroxyarcyriaflavin A (C20H11N3O4 [43]) and 6-hydroxylstaurosporinone (C28H26N4O4 [43]), were isolated from the aethalia of Lycogala epidendrum [77]. Due to its soft pinkish-red young aethalia, easily visible to the naked eye (Figure 2), this cosmopolitan myxomycete is commonly known as wolf’s milk or Groening’s slime [131]. In the same species, arcyriaflavins A and B, as well as lycogaric acid A, were found [51,52,78,79]. The polycyclic pigments lycogarubins A, B (C24H19N3O5 [43]), and C (3,4-bis(indol-3-yl)pyrrole-2,5-dicarboxylic acid), with two derivatives, as well as staurosporinone (also known as K-252) and (Z)-methyl-2-hydroxy-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)acrylate, were also isolated from Lycogala epidendrum [78,80,81,82], and later, their possible synthetic pathways were summarized [132]. These indolocarbazole alkaloids were considered staurosporine analogs [131]. Staurosporine (C24H26N4O3 [43]), a bisondolylmaleimid of the bacterium Streptomyces staurosporeus, is a strong inhibitor of protein kinases that can induce apoptosis and can be useful in anticancer treatment [30,52,133]. K-252 was also previously found in bacteria, particularly in a strain from the genus Nocardiopsis [82,134]. In addition, lycogarubin C had moderate anti-herpes simplex virus (HSV-I) activity [81].

Along with the known 6-hydroxylstaurosporinone, a novel bisindole alkaloid, 6-hydroxy-9′-methoxystaurosporinone was isolated from the fruiting bodies of Ophiotheca chrysosperma [53]. In the same study, another novel, related alkaloid, 6,9′-dihydroxystaurosporinone, was found in Arcyria cinerea [53].

Two new cytotoxic and antiviral bisindole alkaloids, cinereapyrroles A and B, were isolated from the fruiting bodies of Arcyria cinerea together with the already-known arcyriarubin A [51].

Arcyriaflavin D was isolated from the myxomycete Dictydiaethalium plumbeum, and likewise, other arcyriaflavins exhibited moderate activity against bacteria and fungi [30].

Yellow benzodiazepine alkaloid pigments and cycloanthranilylproline derivatives (mainly the novel fuligocandins A and B and FCB) were isolated from field-collected fruiting bodies of Fuligo candida, together with 4-aminobenzoyltryptophan [52,69,70]. Not long after, both cytotoxic fuligocandins A and B were synthesized efficiently [135].

Two other alkaloid pigments, the green makaluvamines A (C11H11N3O [43]) and B (C11H9N3O [43]), were isolated from the fruiting bodies of the acellular slime mold Didymium bahiense [31,65]. Makaluvamine A and the red pigment damirone C (C10H8N2O2 [43]) were produced by another species of the genus Didymium, viz., Didymium iridis [52,65,67]. All these pyrroloiminoquinone pigments are not unique for the slime molds: they had been found earlier in marine sponges such as Zyzzya fuliginosa or Histodermella sp. and have been known for their cytotoxic activity (for details, see [31,52,65,136]).

Novel naphthoquinone pigments that contain a unique alpha-pyrone moiety with a side-chain at the C-3 position were isolated from the methanol extract of the sorocarps of four dictyostelid species: (i) dictyopyrones A (C19H30O3 [43]) and B—from Dictyostelium discoideum and Hagiwaraea rhizopodium (Syn. Dictyostelium rhizopodium Raper and Fennell) [102]; (ii) dictyopyrone C (C19H32O3 [43]) from Dictyostelium longosporum [102]; (iii) dihydrodictyopyrones A (C19H32O3 [43]) and C from Dictyostelium firmibasis [109]. In addition, the production of two unusual bispyrone metabolites with a novel α,α-bispyrone skeleton, modified with long carbon chains, dictyobispyrones B and E, in Dictyostelium giganteum was reported [110].

A novel yellow pigment named fuligoic acid, a peptide lactone with a chlorinated polyene–pyrone acid structure, was isolated from fruiting bodies of Fuligo septica (Syn. Fuligo septica f. flava) [73]. The polyenes physarigins A (C25H28N2O5 [43]), B, and C were discovered in the fruiting bodies of Physarum rigidum, which show structural similarities to physarochrome A and fuligorubin A and absorb UV light [52,95].

The naphthoquinone yellow-to-red pigments trichione and homotrichione were found in the sporophores of different Trichia species, Metatrichia floriformis (Syn. Trichia floriformis) and Metatrichia vesparia [84,85]. The pigment isolated from Metatricha vesparia, vesparione (naphtha[2,3-b]pyrandione derivative), may originate from homoitrichione and has antibiotic properties [29,86]. The more complex pigment TF-1 and simple 2,3,5-trihydroxynaphthoquinone were isolated from Metatrichia floriformis [30]. From the methanol extracts of the fruiting bodies of Lindbladia tubulina, the new cytotoxic naphthoquinone pigments (united as AID 356,150 in [43]), i.e., 6,7-dimethoxydihydrolindbladione, dihydrolindbladione, and 6-methoxydihydro-lindbladione, with a 11,12-saturated side-chain (3-oxyhexyl group) attached to the C-3 position of the naphthoquinone nucleus, were isolated together with the red lindbladione, 7-methoxyl-lindbladione, and 6,7-metoxylindbladione that contain a 11,12-unsaturated side-chain (3-oxyhexyl group) at the same 3-c position [52,62,75,76]. Structurally similar brown-red pigments were found in the acellular slime mold genus Cribraria: (i) Lindbladione was isolated as a major constituent from Cribraria intricata [62], and (ii) three novel dihydrofuranonaphthoquinone pigments, viz., cribrariones A–C, were isolated from Cribraria purpurea, Cribraria cancelata, and Cribraria meylanii, respectively [61,63,64]. Out of them, only cribrarione A proved to be active against Bacillus subtilis [64]. Since both genera Lindbladia and Cribraria belong to the same family Cribrariaceae, it was supposed that lindbladione is one of the common red pigments in all members of this family [52].

The novel polycyclic dibenzofuran pigments, kehokorins A (C27H28O10 [43]), B, and C, which exhibited cytotoxicity against Staphylococcus aureus, were isolated from the fruiting bodies of the acellular Trichia persimilis (Syn. Trichia favoginea var. persimilis) [99].

A pigment related to zeta-carotenes (acyclic carotenoids similar to lycopene [137]) was isolated from the sori of Dictyostelium discoideum [103].

3.1.4. Spore Pigments

Up to now, melanin has been identified as the only pigment of the spores of the explored species from the acellular orders Physarales and Stemonitales (only Stemonitis herbatica), but Reticularia lycoperdon from the order Liceales has an additional ethanol-extractable yellow-green pigment [25,89,96,98,138,139].

3.2. Lipids

The chemically and functionally diverse group of lipids and their derivates are widely recognized as important substances in cosmetics, especially nowadays, when they are used directly, and also as the main constituent of nanoparticles, which enhance the delivery and long-lasting release of dermatologically significant ingredients [42]. The composition and content of fatty acids, phospholipids, di- and triglycerides, sterols, and esters were investigated in both cellular and acellular slime molds [31]. The cosmetic significance of fatty acids such as palmitic (16:0), palmitoleic (9–16:1), and oleic (18:1) acids and some other lipids such as sterols, phospholipids, and glycerolipids has been outlined by different authors (for details, see [42]). Therefore, in the text below, we shall note mainly the novel or rare lipid compounds discovered in slime molds, which may be of interest for use in modern cosmetical products.

3.2.1. Fatty Acids

Fatty acids have broad applications in industrial cosmetics as raw materials in soaps, emollients, emulsifiers, softeners, etc. [140]. The summarizing reviews of the data obtained on the fatty acids of slime molds [31] show the potential of both cellular and acellular slime molds as sources of these valuable natural products for modern cosmetics.

About 50 years ago, the first report on fatty acids in slime molds appeared; it pointed out the high content of unsaturated fatty acids in the cellular Dictyostelium discoideum, in which the unique dienoic acids 5,9–16:2, 5,9–18:2, and 5,11–18:2 were discovered [104]. The major fatty acids of this dictyostelid are represented by the following three metabolic groups: (i) palmitic acid (5%), palmitoleic acid (3%), and a diunsaturated acid, 5,9–16:2 (8%); (ii) a cis-vaccenic acid, 9–18:l (29%) and an 18-carbon diunsaturated acid, 5,11–18:2 (19%); (iii) stearic acid (18:0), oleic acid, and a diunsaturated acid, 5,9–18:2 (32%). In addition, some minor acids were also identified: 17:0, 5–17:1, 5,9–17:2, 19:1, and 20:0 [31].

Further studies of the fatty acids of acellular slime molds (e.g., Physarum polycephalum) also revealed a rich content of unsaturated fatty acids (up to 10% of all fatty acids) (e.g., [31,54]). However, they also showed some differences from the dictyostelids. For example, Physarum does not contain the unique dienoic fatty-acid characteristic of Dictyostellium discoideum [31]. Fatty acids were examined in Arcyria cinerea, Arcyria denudata, Arcyria obvelata, Fuligo septica, Lycogala epidendrum, Lycogala flavofuscum, Physarium sp., Trichia favoginea, and Trichia varia [31,54]. In each of them, 21 saturated fatty acids (mostly 16:0, which comprise 4.55–9.29%), 27 monoenoic (from 7–14:1 to 9–24:1, with interesting isomers of docosaenoic acid 22:1), 12 dienoic (31–54%, mostly four major isomers of 18:2 and trace isomers of 20:2), and 14 polyenoic fatty acids (8–18%, tri- and tetraenoic acids only) were determined in different proportions [31,54]. A novel multibranched polyunsaturated fatty acid (2E,4E,7S,8E,10E,12E,14S)-7,9,13,17-tetramethyl-7,14-dihydroxy-2,4,8,10,12,16-octadecahexaenoic acid) was discovered in seven of those slime molds [55] (Table 1).

Rare fatty acids, all-cis 5,9–16:2, 5,9–18:2, 5,11,14–20:3, 5,11,14,17–20:4, 7,13–22:2, and 7,15–22:2, were identified only in two slime molds, viz., Trichia favoginea and Trichia varia [31,54]. It was supposed that they should have antimicrobial activity because compounds with similar structures (i.e., fatty acids with a Δ5,9-position of two double bonds) were particularly active against Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphyllococcus aureus and Staphyllococcus faecalis [29].

A novel bioactive lipid, cyclic phosphatidic acid (CPA), was first isolated from Physarum polycephalum [94] and, afterward, detected in a wide range of organisms, including humans [31]. CPA specifically inhibits cancer cell invasion and metastasis, has a neurotrophic effect, and exhibits antimitogenic regulation of the cell cycle [94]. A novel all-cis-5,9,12-heptadecatrienoic acid was discovered in the cellular slime mold Heterostelium pallidum (Syn. Polysphondylium pallidum Olive) [114,115].

3.2.2. Sterols

Secondary triterpenoid metabolites, sterols, are components of cell membranes, essential in controlling their stability, fluidity, and permeability. Moreover, sterols influence the functionality of enzymes, receptors, and channels and are antioxidants that also have antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, and anticarcinogenic properties (for details, see [42]). Despite the paucity of studies of sterols in slime molds, the results of their diversity are promising for future studies.

In the cellular Dictyostelium discoideum, stigmast-22-en-3b-ol (C29H50O [43]) was identified as the major sterol ([31]).

In the acellular Physarum polycephalum, the following eight sterols were reported: stigmasterol (C29H48O [43]), b-sitosterol (C29H50O [43]), stigmastanol (C29H52O [43]), campesterol (C28H48O [43]), campestanol (C28H50O [43]), cholesterol (C27H46O [43]), lanosterol (C30H50O [43]), and 24-methylene dihydrolanosterol (C34H60O [43]) (for details, see [31]). Clionasterol (C25H50O [43] was found in the acellular slime mold Didymiun squamulosum [68].

3.2.3. Phospholipids

Phospholipids are the natural, essential components of cell membranes that are applied in cosmetics as excellent emulsifying agents for the stabilization of oil–water emulsions as delivery systems (for details, see [42]). Investigations into slime molds started in the middle of the 1960s [141]. According to the review by Dembitsky et al. [31], most studies concern Physarum polycephalum, but data on the phospholipid composition of other myxomycetes, such as Arcyria sp., Fuligo septica, and Trichia varia, are also available and concern 12 compounds. In all these species, the main components (49–52%) were amino phospholipids with the domination of alkyl forms [31]. Among them, the most important were phosphatidylcholine/lecithin (PC—ca. 50%), phosphatidyletanolamine/cephalin (PE—ca. 40%), and phosphatidylinositol (ca. 7%), with unusually high amounts of alk-1-enylacyl and alkyl-acyl derivatives [31]. Oleic acid, linoleic acid, and a 20:2 acid were the main fatty acid moieties of phospholipids [31].

3.2.4. Glycerolipids

Glycerolipids comprise a diverse group of very attractive in-dermal cosmetics glycerol-containing lipids with an amphiphilic nature that exerts therapeutic antiviral, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory activities through interaction with other biological molecules (for details, see [42,142]).

Bahiensol, a novel monoalkyl-glycerol isolated from the plasmodium of Didymium bahiense var. bahiense, exhibited antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis [66]. Seven other novel and unusual lipids, three polyacetylene triglycerides, and four acylglycerols from Lycogala epidendrum were named lycogarides A–C and lycogarides D–G, respectively [79,80]. Lycogaride A, C56H72O9, has been registered as 1,2,3-(8R,9R-epoxy-17E-octadecen-4,6-diynoyl)-sn-glycerol [43].

3.2.5. Esters and Lactones

Esters are important emollients and solubilizers in the personal care cosmetic industry [141]. Lactones are also esters, in which the ester forms a ring structure, but they are much less common in cosmetics [143]. Volatile members of both groups are mostly used as flavor and fragrance components [143]. Some of the lactones have been identified among the pigments discovered in slime molds and, as such, were described in the first paragraph of this review. Below, some novel and yet not commercially explored compounds of esters and lactones are noted.

Enteridinines A and B are two novel deoxysugar esters discovered in the acellular Reticularia lycoperdon (Syn. Enteridium lycoperdon) [97], also known as false puffball due to its white aethalia [144]. They contain 1,7-dioxaspiro[5.5]undecanes with an O-beta-D-mycarosyl-(1-->4)-beta-D-olivosyl unit and an O-beta-L-olivomycosyl-(1-->4)-beta-D-amicetosyl-(1-->4)-beta-L-digitoxosyl unit, and due to their unique structures, they inhibit the growth of Gram-positive bacteria [97].

Melleumin A, a novel peptide lactone that contains an unusual amino acid, a tyrosine-attached acetic acid, and its seco acid methyl ester, melleumin B, was isolated from the plasmodium of Physarum melleum [88]. It absorbs UV light but has no antimicrobial or cytotoxic activities [52].

3.3. Glycosides

Four novel glycosides that contain the glucose, mannose, and rhamnose of a novel multibranched polyunsaturated fatty acid (2E,4E,7S,8E,10E,12E,14S)-7,9,13,17-tetramethyl-7,14-dihydroxy-2,4,8,10,12,16-octadecahexaenoic acid) were discovered in seven different myxomycetes (i.e., Arcyria cinerea, Arcyria denudata, Arcyria obvelata, Fuligo septica, Lycogala epidendrum, Physarum polycephalum, and Trichia varia) [55].

Novel polypropionate lactone glycosides have been isolated from Lycogala epidendrum [83]. These compounds, named lycogalinosides A (C38H60O11 [145]) and B, contain a 2-deoxy-alpha-L-fucopyranosyl-(1-4)-6-deoxy-beta-D-gulopyranosyl unit and a beta-D-olivopyranosyl-(1-4)-beta-D-fucopyranosyl unit. This unique structure was considered responsible for their antimicrobial activity, expressed as the inhibition of Gram-positive bacteria [83,146].

Fulicineroside (C50H72O15 [43]), a glycosidic dibenzofuran metabolite, is a novel aromatic compound isolated from Fuligo cinerea, with high-level activity against Gram-positive bacteria and crown gall tumors [71]. Other novel aromatic heterocyclic dibenzofurans, dictyomedins A (C21H16O7 [43]) and B (C20H14O6 [43]), were isolated from the methanol extracts of the sorocarps of Dictyostelium medium [43,111]. From the methanol extract of the fruiting bodies of another dictyostellid, Heterostelium tenuissimum (Syn. Polysphondylium tenuissimum), five prenylated and geranylated aromatic compounds, abbreviated as Pt-1–5, were obtained [116].

An additional aromatic compound, the so-called active principle Ppc-1, was isolated from the fruiting bodies Heterostelium pseudocandidum (Syn. Polysphondylium pseudocandidum H. Hagiw.) [116]. It was identified as diisopentenyloxy quinolobactin derivative 3-methylbut-2-enyl-4-methoxy-8-[(3-methylbut-2-enyl)oxy] quinoline-2-carboxylate [147]. This biologically active compound is able to permeate the cell membrane and is active against the Gram-negative periodontopathogenic bacteria Porphyromonas gingivalis [145]. In parallel, Ppc-1 can affect the lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-I-B activation considered a signaling pathway in inflammatory mediator secretion [145]. Therefore, Ppc-1, which exhibits a dual antibacterial and anti-inflammatory action, may be a promising targeted agent for periodontal diseases, useful in modern dental cosmetics.

3.4. Proteins

Fatty-acid desaturases, including Delta-5 and Delta-6 desaturases, are enzymes that are important for cosmetics because they participate in the synthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acids and contribute to maintaining cell-membrane fluidity during temperature changes [148]. The first finding of the cDNA and genomic sequences of a Delta-5 desaturase in slime molds was in the cellular Dictyostelium discoideum [105].

A secondary metabolite of the SteelyA polyketide synthase 4-methyl-5-pentylbenzene-1,3-diol (MPBD) of Dictyostelium discoideum had antimicrobial activities toward Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, which are Gram-negative and Gram-positive, respectively [106].

Myosins, important proteins for various motile activities, have been purified and studied in detail in slime molds as model organisms for the investigation of cytokinesis and cell movements [107,108]. There are 35 classes of myosins, also known to be involved in cell adhesion, endocytosis, and exocytosis, but the implementation of myosin 10 in the skin pigmentation of mice has been demonstrated [149]. Myosin 10 plays the role of a motor for the transportation of important-for-skin-pigmentation melanin, containing granules (melanosomes) from the cells of their origin (melanocytes) to the neighboring keratinocytes in the skin epidermis [149]. Considering that skin pigmentation plays a critical role in protection against the harmful effects of UV radiation [149], such results are of interest for the creation of skin-protective cosmetic products.

3.5. Exopolysaccharides

Mucous secretions from the aquatic extracts of the plasmodium of Licea variabilis (Syn. Licea flexuosa) possess antibacterial and antifungal activity [29,74]. Exopolysaccharides from Physarella oblonga and Physarum polycephalum, which largely consist of carbohydrates (comprising the following monomers: galactose, glucose, and rhamnose), proteins, and various sulfate groups, were significantly active against Candida albicans [87].

3.6. Aromatic Compounds

Besides the aromatic compounds fulicineroside, dictyomedins A and B, Pt-1–5, and Ppc, discussed above together with other glycosides, a novel aromatic dibenzofuran that inhibited the growth of Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Staphyllococcus pyogenes was obtained from the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium purpureum K1001 and labeled as AB0022A [112]. Its dehalogenated derivative was identified as 1,9-dihydroxy-3,7-dimethoxy-2-hexanoyl-4,6,8-trichlorodibenzofuran [112]. We note this aromatic compound because natural aromatic and cyclic chemicals with antimicrobial activity are in great demand in perfumes and other cosmetical products [29,150].

Other aromatic compounds of interest for cosmetics are terpenes that enhance skin penetration, can help control sebum levels in the skin, and are anti-inflammatory and detoxifying agents [151]. Two novel terpenes were isolated from cellular slime molds: (i) mucoroidiol, a protoilludane-type sesquiterpene with osteoclast-differentiation inhibitory activity from Dictyostelium mucoroides, and (ii) firmibasiol, a geranylated sesquiterpene from Dictyostelium firmibasis [10]. The cyclic triterpenes tubiferals A (C30H42O5 [43]) and B were discovered in the field aethalia of the acellular slime mold Tubifera dimorphotheca [52,100]. Out of these terpenes, only tubeferal A showed strong activity against vincristine-resistant human epithelial carcinoma cells (abbreviated as KB cell lines) [100].

Two new chlorinated benzofurans, Pf-1 and Pf-2, were isolated from the methanol extract of sorocarps of the cellular Heterostelium filamentosum (Syn. Polysphondylium filamentosum F. Traub, H.R. Hohl and Cavender) and displayed inhibitory activities in cell proliferation in mammalian cells [113].

The methanol extracts of the sorocarps of Dictyostelium brefeldianum and Dictyostelium giganteum were the sources for a new aromatic compound, brefelamide, cytotoxic for human astrocytoma cells [101,152,153,154]. Brefelamide (C22H20N2O5) is registered as N-(3-(2-amino-3-(4-hydroxyphenoxy)phenyl)-3-oxopropyl)-4-hydroxybenzamide in [43].

3.7. Safety Aspects

Most of the species and compounds mentioned in the review are considered non-toxic and safe. However, the very few studies that have been carried out have demonstrated that the spores produced by slime molds can be significant aeroallergens [155]. For example, the spores of Fuligo septica may trigger allergic rhinitis or episodes of bronchial asthma in susceptible people [156,157]. In another study, based on allergen extracts of nine myxomycetes (i.e., Arcyria cinerea, Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa, Fuligo septica, Hemitrichia clavata, Lycogala epidendrum, Metatrichia vesparia, Stemonitis nigrescens, Trichia favoginea, and Tubifera ferruginosa), forty-two percent of subjects with a history of severe acute respiratory symptoms (SARS) were sensitized [155].

Among the sterols of slime molds, only stigmastanol has been identified as an irritant [43]. Of the results obtained, considering that the sources of valuable natural products are the plasmodia/pseudoplasmodia and fruiting bodies, at present, it is possible that careful use, along with relevant preliminary research, will allow these fascinating slime molds to find application as an interesting reservoir of unusual natural ingredients for the modern cosmetic industry.

4. Discussion

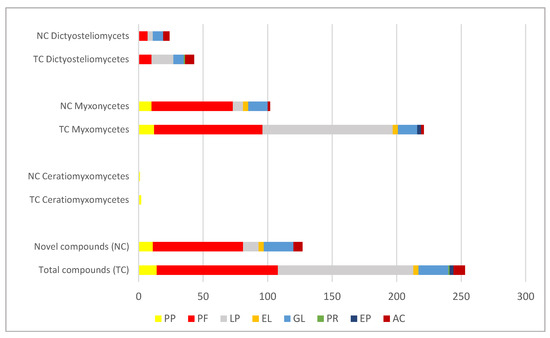

An analysis of the results obtained during our search, conducted almost 30 years after the first comprehensive exploration of slime mold chemistry [30], once more demonstrates that these peculiar, fascinating organisms produce a plethora of secondary metabolites, 251 of which are discussed in the present review. Logically, this current number is significantly higher than the previous estimates of more than 100 secondary metabolites of slime molds [31,36]. The highest number of chemical substances is reported to be from Myxomycetes (221), followed by Dictyosteliomycetes (44) and Ceratiomyxomycetes (2) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Number of chemical compounds isolated from the slime molds, outlining the number of total (TC) and novel (NC) substances as well as the distribution of substances by chemical groups and by taxonomic classes. Legend: PP—pigments from plasmodia; PF—pigments from fruiting bodies; LP—lipids; EL—esters and lactones; GL—glycosides; PR—proteins; EP—exopolysaccharides; AC—aromatic compounds.

The best studied are the pigments (107), most of which have been isolated from the fruiting bodies (94) and less (14) from the plasmodia, with lindbladione as a common pigment for both stages of the life cycle. It is possible to suppose that these results reflect the methodology and aims of the studies conducted so far since most studies were oriented toward pigment extractions from fruiting bodies. On the other side, the higher number of pigments in acellular slime molds (84 in the fruiting bodies and 12 in the plasmodia) compared to the cellular slime molds (10 pigments in the fruiting bodies) is obviously due to the much greater diversity of fruiting body types and colors in myxomycetes. Most pigments belong to the yellow–orange–red gamma and include tetramic acids, lactones, and alkaloids. They have been especially outlined in the review and separated from the other chemical compounds due to their great but yet-unexplored potential in modern cosmetics. Lipids, with a total of 105 diverse compounds (mostly fatty acids), are the second-most studied group by richness in slime molds. Considerably less attention in the biochemical studies was paid to esters, lactones, glycosides, enzymes, and exopolysaccharides.

The number of novel compounds found in the slime molds is 127 and is notably higher in Myxomycetes (102) than in Dictyosteliomycetes (24) and Ceratiomyxomycetes (1) (Figure 3). However, the percentage of new substances in both last taxonomic classes is much higher (>50%) (Figure 3). The pigments of fruiting bodies comprise the biggest part of the isolated novel substances (84). Considerably fewer novel substances (12) have been characterized from the large group of lipids, contrasting with almost all new substances found among the aromatic compounds, esters, lactones, and glycosides (Figure 3). All these groups provide significant ingredients for the cosmetic industry and, therefore, the finding of 23 novel glycosides, 9 novel aromatic terpenes, 2 novel esters, and 2 novel lactones sounds very promising for the future application and search of novel products from unusual sources, such as the slime molds.

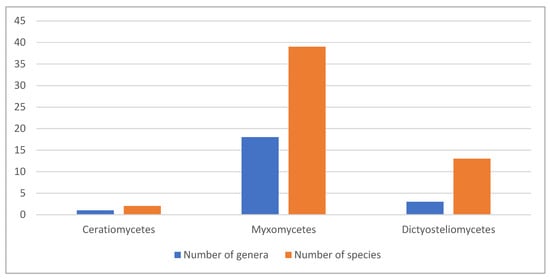

Data on the compounds of interest for the cosmetics industry are available for 54 species. This comprises quite a small part, only 0.06% of the total biodiversity of slime molds, which comprises more than 900 species [8,9]. Most explored species are from the Myxomycetes (39 species from 18 genera), followed by cellular Dictyosteliomycetes (13 species from three genera) and Ceratiomycetes (two species from a single genus) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Number of explored genera and species from the three classes of slime molds.

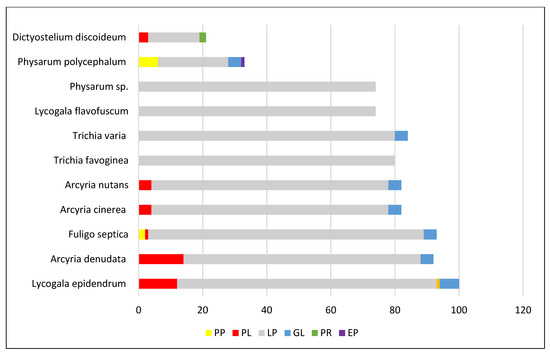

The highest number of all substances isolated from a single species is 99 from the cosmopolitan, acellular slime mold Lycogala epidendrum, which is widespread on decaying wood. It is followed by the acellular Arcyria denudata (92 compounds), Fuligo septica (85), Trichia varia (84), Arcyria cinerea and Arcyria obvelata (with 82 substances from each of them), Trichia favoginea (80), and Physarum sp. (74) (Figure 5). From 11 species, only 1 substance was isolated; 2 to 7 substances were found in 21 species, whereas 25 and 21 substances were discovered in Physarum polycephalum and Dictyostelium discoideum, respectively. These relatively low numbers, at first glimpse, look strange because these two slime molds are the ones most cultivated and explored as model organisms [10,11,12,13]. Most probably, the higher number of natural compounds discovered in the genera Lycogala, Arcyria, Fuligo, and Trichia (Figure 5) can be explained by the wide distribution and bright yellow-, pink-, or red-colored fruiting bodies of these species, easily seen in nature with the naked eye.

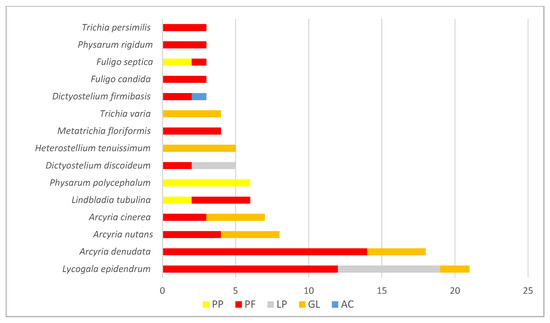

Figure 5.

Number of compounds isolated from the richest slime molds. Legend: PP—pigments from plasmodia; PF—pigments from fruiting bodies; LP—lipids; GL—glycosides; PR—proteins; EP—exopolysaccharides.

Novel compounds have been isolated from 39 species, which comprise 72% of all species studied but just 0.04% of all known slime molds. From 16 species, only one novel substance was isolated, and from 8 species, two substances were isolated. The highest number of novel compounds was found in Lycogala epidendrum (21) and Arcyria denudata (18), while in the other 13 species, the number of novel substances was much lower, varying from eight (in Arcyria obvelata) to three (in five slime molds such as the acellular Fuligo candida, Fuligo septica, Physarum rigidum, Trichia persimilis, and in the cellular Dictyostelium fimbriatum) (Figure 6). The novel compounds isolated from seven of the most explored species belonged to one chemical group; in eight species, they were from two different groups, and only in Lycogala epidendrum, the novel substances were from three groups (pigments, lipids, and glycosides) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Number of novel substances isolated from the richest and most explored slime molds. Legend: PP—pigments from plasmodia; PF—pigments from fruiting bodies; LP—lipids; GL—glycosides; AC—aromatic compounds.

5. Conclusions

The 251 natural substances discussed in the present review include 127 diverse novel valuable metabolites discovered in 72% of the explored species. Such a palette of natural, biologically active compounds offers a wide-open field for future research related to their practical application in different industries, cosmetics in particular. This is especially valid for the natural yellow-to-red pigments, which may be important in cosmetic formulations applied to lipsticks, nail polishes, etc., and also for lipids, polysaccharides, and various aromatic compounds. At the same time, our analysis reveals that only a few, 53 from all 900 known slime molds, have been investigated so far. This comprises less than one percent of all known species and is also noted in previous reviews and explained by the difficult cultivation of some of the slime molds (e.g., [29,30]). In support of this explanation is the fact that most of the newly isolated substances were extracted from fruiting bodies collected in the field. Therefore, one of the challenges for future commercial cosmetic applications of slime mold substances is the optimization and lowering of the efforts and expenses for their mass cultivation. Doubtless, much more intensive studies are necessary in order to investigate the biochemical potential of all slime molds. Such studies are also necessary from the safety aspect, despite the fact that few slime molds seem to be dangerous, and this concerns mostly the aero-allergenic potential of spores, which are not applicable in cosmetic formulations.

In spite of the fact that knowledge of the biochemical composition and unusual secondary metabolites of the peculiar slime molds is still far from being sufficient, the results obtained so far demonstrate that they produce a palette of novel, unusual, and rare substances as secondary metabolites. Many of the compounds are multifunctional and, in addition to their physiological roles as pigments, lipids, polysaccharides, aromatic compounds, etc., they exhibit antibiotic or cytotoxic effects, and some of them absorb UV rays. In this way, they provide additional value and are important, potentially unusual, natural, high-quality ingredients for the cosmetics industry that can meet the burgeoning demands of modern society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.-G., M.A. and K.I.; writing—review and editing, M.S.-G., G.G. and B.U.; visualization, M.S.-G. and B.U.; supervision, G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Seca, A.M.L.; Moujir, L. Natural Compounds: A Dynamic Field of Applications. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A. Natural products chemistry: The emerging trends and prospective goals. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amberg, N.; Fogarassy, C. Green Consumer Behavior in the Cosmetics Market. Resources 2019, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desam, N.; Al-Rajab, A. The Importance of Natural Products in Cosmetics. In Bioactive Natural Products for Pharmaceutical Applications; Pal, D., Nayak, A.K., Eds.; Advanced Structured Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyneva-Gärtner, M.; Uzunov, B.; Gärtner, G. Enigmatic microalgae from aeroterrestrial and extreme habitats in cosmetics: The potential of the untapped natural sources. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masamiishibashi. Search for Bioactive Natural Products from Unexploited Microbial Resources. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta-ur-Rahman, Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 29, Part J, pp. 223–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, S.L. Secretive Slime Molds. Myxomycetes of Australia; CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, S.L.; Rojas, C. (Eds.) Myxomycetes: Biology, Systematics, Biogeography and Ecology; Elsevier Academic Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, C.; Stephenson, S.L. (Eds.) Myxomycetes: Biology, Systematics, Biogeography and Ecology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, H.; Kubohara, Y.; Ishigaki, H.; Takahashi, K.; Eguchi, H.; Sugawara, A.; Oshima, Y.; Kikuchi, H. Two new terpenes isolated from Dictyostelium cellular slime molds. Molecules 2020, 25, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pears, C.J.; Gross, J.D. Microbe Profile: Dictyostelium discoideum: Model system for development, chemotaxis and biomedical research. Microbiology 2021, 167, 001040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, S.; Thulin, M.; Cavender, J.C.; Escalante, R.; Kawakami, S.; Lado, C.; Landolt, J.; Nanjundiah, V.; Queller, D.; Strassmann, J.; et al. A new classification of the Dictyostelids. Protists 2017, 169, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussard, A.; Fessel, A.; Oettmeier, C.; Briard, L.; Döbereiner, H.-G.; Dussutour, A. Adaptive behaviour andlearning in slime moulds: The role ofoscillations. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 2021, B376, 20190757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, D.H. What is STEM education and why it is important? JFATE 2014, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf, S.L.; Strassmann, J.E. Dictyostelia. In Handbook of the Protists, 2nd ed.; Simpson, A.G.B., Archibald, J.M., Slamovits, C.H., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg/Germany, Germany, 2017; pp. 1433–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos, C.J.; Mims, C.W.; Blackwell, M. Introductory Mycology; Wiley India Pvt. Limited: New Delhi, India, 2007; pp. 1–880. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, S.L.; Stempen, H. Myxomycetes. A Handbook of Slime Molds, 1st ed.; Paperback Edition Printed 2000; Timber Press Inc.: Portland, OR, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Adl, S.M.; Bass, D.; Lane, C.E.; Lukeš, J.; Schoch, C.L.; Smirnov, A.; Agatha, S.; Berney, C.; Brown, M.W.; Burki, F.; et al. Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2018, 66, 4–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turland, N.J.; Wiersema, J.H.; Barrie, F.R.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Knapp, S.; Kusber, W.-H.; Li, D.-Z.; Marhold, K.; et al. International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants (Shenzhen Code) Adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017 (Electronic ed.); Glashütten: International Association for Plant Taxonomy: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.; Everhart, S. Importance of Myxomycetes in Biological Research and Teaching. Pap. Plant Pathol. 2010, 366, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Leontyev, D.V.; Schnittler, M.; Stephenson, S.L.; Novozhilov, Y.K.; Shchepin, O.N. Towards a phylogenetic classification of the Myxomycetes. Phytotaxa 2019, 399, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Weber, R.W.S. Introduction to Fungi, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 1–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, J. The Social Amoebae: The Biology of Cellular Slime Molds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 1–126. [Google Scholar]

- Stoyneva-Gärtner, M.; Uzunov, B. Bases of Systematics of Algae and Fungi; JAMG Books: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2017; pp. 1–189. [Google Scholar]

- Krzywda, A.; Petelenz, E.; Michalczyki, D.; Płonka, P. Sclerotia of the acellular (true) slime mould Fuligo septica as a model to study melanization and anabiosis. CMBL 2008, 13, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woyzichovski, J.; Shchepin, O.N.; Schnittler, M. High environmentally induced plasticity in spore size and numbers of nuclei per spore in Physarum albescens (Myxomycetes). Protist 2022, 173, 125904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, S.L.; Fiore-Donno, A.M.; Schnittler, M. Myxomycetes in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 2237–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loquin, M.; Prevot, A.R. Etude de quelque antibiotiques produits par les myxomycetes. Ann Inst Pasteur 1948, 75, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tafakori, V. Slime molds as a valuable source of antimicrobial agents. AMB Express 2021, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steglich, W. Slime molds (myxomycetes) as a source of new biological active metabolites. Pure Appl. Chem. 1989, 61, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.; Rezanka, T.; Spızek, J.; Hanus, L. Secondary metabolites of slime molds (myxomycetes). Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 747–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, M. Study on myxomycetes as a new source of bioactive natural products. YakugakuZasshi 2007, 127, 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baba, H.; Sevindik, M.; Dogan, M.; Akgul, H. Antioxidant, antimicrobial activities and heavy metal contents of some myxomycetes. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2020, 9, 7840–7846. [Google Scholar]

- Kubohara, Y.; Kikuchi, H. Dictyostelium: An important source of structural and functional diversity in drug discovery. Cells 2019, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubohara, Y.; Oshima, Y.; Shiratsuchi, Y.; Ishigaki, H.; Takahashi, K.; Kikuchi, H. Antimicrobial activities of Dictyosteliumdiferentiation-inducing factors and their derivatives. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Lin, N.; Wu, B. Laboratory culture and bioactive natural products of myxomycetes. Fitoterapia 2020, 146, 104725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevindik, M.; Baba, H.; Bal, C.; Colak, O.; Akgul, H. Antioxidant, oxidant and antimicrobial capacities of Physarum album (Bull.) Chevall. JBMOA 2018, 6, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yokota, M.; Nitta, K. Purification and some properties of hemagglutinin from the myxomycete Physarum polycephalum. Experientia 1996, 52, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, H.; Saito, Y.; Komiya, J.; Takaya, Y.; Honma, S.; Nakahata, N.; Ito, A.; Oshima, Y. Furanodictine A and B: Amino sugar analogues produced by cellular slime molds Dictyostelium discoideum showing neuronal differentiation activity. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 6982–6987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, A.; Ahmad, I.; Fatima, N.; Ansari, V.; Akhtar, J. Algal bioactive compounds in the cosmeceutical industry: A review. Phycologia 2017, 56, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J. Lipid nanoparticles-based cosmetics with potential application in alleviating skin disorders. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyneva-Gärtner, M.; Uzunov, B.; Gärtner, G. Aeroterrestrial and extremophilic microalgae as promising sources for lipids and lipid nanoparticles in dermal cosmetics. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Taxonomy Browser. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Index Fungorum. Available online: http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/names.asp (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Walimbe, S. Global Cosmetic Pigments Market Size Is Anticipated to Cross USD 1 Billion by 2026. Available online: https://www.hpci-events.com/global-cosmetic-pigments-market-size-is-anticipated-to-cross-usd-1-billion-by-2026/#:~:text=Pigments%20are%20used%20in%20various%20formulations&text=One%20of%20the%20most%20integral,personal%20care%20items%20like%20soap (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Guerra, E.; Llompart, M.; Garcia-Jares, C. Analysis of Dyes in Cosmetics: Challenges and Recent Developments. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wormington, W.M.; Weaver, R.F. Photoreceptor pigment that induces differentiation in the slime mold Physarum polycephalum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1976, 73, 3896–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.M. A Field Guide to the Fungi of Australia; University of New South Wales Press Ltd.: Sydney, Australia, 2005; ISBN 9780868407425. [Google Scholar]

- Velten, R.; Josten, I.; Steglich, W. Ungesättigte 6-Alkylpyrone aus dem Schleimpilz Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa (Myxomycetes). Liebigs Ann. 1995, 1, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, K.; Kiyota, M.; Naoe, A.; Nakatani, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Komiyama, K.; Yamori, T.; Ishibashi, M. New bisindole alkaloids isolated from myxomycetes Arcyria cinerea and Lycogala epidendrum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 53, 594–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishibashi, M. Isolation of bioactive natural products from myxomycetes. Med. Chem. 2005, 1, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shintani, A.; Toume, K.; Rifai, Y.; Arai, M.; Ishibashi, M. A bisindole alkaloid with hedgehog signal inhibitory activity from the myxomycete Perichaena chrysosperma. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 1711–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Řezanka, T. Polyunsaturated and unusual fatty acids from slime moulds. Phytochemistry 1993, 33, 1441–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Řezanka, T. Glycosides of polyenoic branched fatty acids from myxomycetes. Phytochemistry 2002, 60, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steglich, W.; Steffan, B.; Kopanski, L.; Eckhardt, G. Pilzpigmente, 36. Indolfarbstoffe aus Fruchtkörpern des Schleimpilzes Arcyria denudata. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1980, 19, 459–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, G.; Wille, G.; Brenner, M.; Zeitler, K.; Steglich, W. Total synthesis of the slime mold alkaloids arcyroxocin A and B. Synth 2011, 2, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, K.; Suetsugu, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Komiyama, K.; Ishibashi, M. Bisindole Alkaloids from Myxomycetes Arcyria denudata and Arcyria obvelata. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1252–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, S.; Naoe, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamauchi, T.; Yamaguchi, N.; Ishibashi, M. Isolation of bisindole alkaloids that inhibit the cell cycle from Myxomycetes Arcyria ferruginea and Tubifera casparyi. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 2879–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniwa, K.; Arai, M.A.; Li, X.; Ishibashi, M. Synthesis, determination of stereochemistry, and evaluation of new bisindole alkaloids from the myxomycete Arcyria ferruginea: An approach for Wnt signal inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 4254–4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, D.; Ishibashi, M.; Yamamoto, Y. Cribrarione B, a new naphthoquinone pigment from the myxomycete Cribraria cancellata. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 1611–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misono, Y.; Ishikawa, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Komiyama, K.; Ishibashi, M. Dihydrolindbladiones, three new naphthoquinone pigments from a myxomycete Lindbladia tubulina. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 999–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintani, A.; Yamazaki, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ahmed, F.; Ishibashi, M. Cribrarione C, a naphthoquinone pigment from the myxomycete Cribraria meylanii. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 57, 894–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naoe, A.; Ishibashi, M.; Yamamoto, Y. Cribrarione A, a new antimicrobial naphthoquinone pigment from a myxomycete Cribraria purpurea. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 3433–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, M.; Iwasaki, T.; Imai, S.; Sakamoto, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ito, A. Laboratory culture of the myxomycetes: Formation of fruiting bodies of Didymium bahiense and its plasmodial production of makaluvamine A. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misono, Y.; Ishibashi, M.; Ito, A. Bahiensol, a new glycerolipid from a cultured myxomycete Didymium bahiense var. bahiense. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 612–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nakatani, S.; Kiyota, M.; Matsumoto, J.; Ishibashi, M. Pyrroloiminoquinone pigments from Didymium iridis. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2005, 33, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, M.; Mitamura, M.; Ito, A. Laboratory culture of the myxomycete Didymium squamulosum and its production of clionasterol. Nat. Med. 1999, 53, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Komiyama, K.; Ishibashi, M. Cycloanthranilylproline-derived constituents from a myxomycete Fuligo candida. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 52, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, H.; Yamada, Y.; Komiyama, K.; Hayashi, M.; Ishibashi, M.; Sunazuka, T.; Izuhara, T.; Sugahara, K.; Tsuruda, K.; Masuda, M.; et al. A novel natural compound, a cycloanthranilylproline derivative (Fuligocandin B), sensitizes leukemia cells to apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) through 15-deoxy-Delta 12, 14 prostaglandin J2 production. Blood 2007, 110, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Řezanka, T.; Hanuš, L.O.; Dvořáková, R.; Dembitsky, V.M. The fulicineroside, a new unusual glycosidic dibenzofuran metabolite from the slime mold Fuligo cinerea. Wiggers Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 13, 2708–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casser, I.; Steffan, B.; Steglich, W. The Chemistry of the Plasmodial Pigments of the Slime Mold Fuligo septica (Myxomycetes). Angew. Chem. 1987, 26, 586–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintani, A.; Toume, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ishbibashi, M. Dehydrofuligoic acid, a new yellow pigment isolated from the myxomycete Fuligo septica f. flava. Heterocycles 2010, 82, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobels, J.C. Nutrition de quelque myxomycetes en cultures et associees et leurs proprietes antibiotiques. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek J. Microbiol. Serol. 1950, 16, 123–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Ishibashi, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Komiyama, K. Lindbladione and related naphthoquinone pigments from a myxomycete Lindbladia tubulina. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 1126–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, M.A.; Makita, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Kawano, H.; Suganami, A.; Tamura, Y.; Ishibashi, M. Total synthesis of lindbladione, a Hes1 dimerization inhibitor and neural stem cell activator isolated from Lindbladia tubulina. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosoya, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Uehara, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Komiyama, K.; Ishibashi, M. New cytotoxic bisindole alkaloids with protein tyrosine kinase inhibitory activity from a myxomycete Lycogala epidendrum. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 2776–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröde, R.; Hinze, C.; Josten, I.; Schmidt, B.; Steffan, B.; Steglich, W. Isolation and synthesis of 3,4-bis(indol-3-yl)pyrrole-2,5-dicarboxylic acid derivatives from the slime mould Lycogala epidendrum. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 1689–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Akazawa, A.; Tori, M.; Kan, Y.; Kusumi, T.; Takahashi, H.; Asakawa, Y. Three novel polyacetylene triglycerides, lycogarides A–C, from the myxomycetes Lycogala epidendrum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1994, 42, 1531–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, M.; Hashimoto, T.; Asakawa, Y. Acylglycerols from the slime mold, Lycogala epidendrum. Phytochemistry 1996, 41, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Yasuda, A.; Akazawa, K.; Takaoka, S.; Tori, M.; Asakawa, Y. Three novel dimethyl pyrroledicarboxylate, lycogarubins A-C, from the myxomycetes Lycogala epidendrum. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 2559–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuzawa, T.; Iida, T.; Yoshida, M.; Hirayama, N.; Takahashi, M.; Shirahata, K.; Sano, H. The structures of the novel protein kinase C inhibitors K-252a, b, c and d. J. Antibiot. 1986, 39, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Řezanka, T.; Dvořáková, R. Polypropionate lactones of deoxysugars glycosides from slime mold Lycogala epidendrum. Phytochemistry 2003, 63, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopanski, L.; Li, G.; Besl, H.; Steglich, W. Pilzpigmente, 41. Naphthochinon-Farbstoffe aus den Schleimpilzen Trichia floriformis und Metatrichia vesparium (Myxomycetes). Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1982, 1982, 1722–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopanski, L.; Karbach, G.; Selbitschka, G.; Steglich, W. Pilzfarbstoffe, 53. Vesparion, ein Naphtho(2,3-b)pyrandion-Derivat aus dem Schleimpilz Metatrichia vesparium (Myxomycetes). Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1987, 1987, 793–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffan, B.; Praemassing, M.; Steglich, W. Physarochrome A, a plasmodial pigment from the slime mould Physarum polycephalum (Myxomycetes). Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.; Phung, T.; Stephenson, S.; Tran, H. Biological activities and chemical compositions of slime tracks and crude exopolysaccharides isolated from plasmodia of Physarum polycephalum and Physarella oblonga. BMC Biotechnol. 2017, 17, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, S.; Kamata, K.; Sato, M.; Onuki, H.; Hirota, H.; Matsumoto, J.; Ishibashi, M. Melleumin A, a novel peptide lactone isolated from the cultured myxomycete Physarum melleum. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płonka, P.M.; Rakoczy, L. Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR) as a method for studying the biology of the acellular slime moulds (Myxomycetes). Acta Physiol. Plant 1997, 19, 233. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, A.; Steffan, B. Polycephalin B and C: Unusual tetramic acids from plasmodia of the slime mold Physarum polycephalum (Myxomycetes). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1998, 37, 3139–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, F.; Polborn, K.; Steffan, B. The absolute configuration of polycephalin C from the slime mold Physarum polycephalum (Myxomycetes). Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 8433–8437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longbottom, D.; Morrison, A.; Dixon, D.; Ley, S. Total synthesis of the polyenoyltetramic acid polycephalin C. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 6955–6966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbarth, S.; Steffan, B. Structure and biosynthesis of chrysophysarin A, a plasmodial pigment from the slime mould Physarum polycephalum (myxomycetes). Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Mukai, M.; Murofushi, H.; Tigyi, G.; Murakami-Murofushi, K.; Uchiyama, A.; Fujiwara, Y.; Kobayashi, T. Biological functions of a novel lipid mediator, cyclic phosphatidic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1582, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misono, Y.; Ito, A.; Matsumoto, J.; Sakamoto, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ishibashi, M. Physarigins A–C, three new yellow pigments from a cultured myxomycete Physarum rigidum. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 4479–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, P.; Paramasivan, P.; Kalyanasundaram, I. Melanin as the spore wall pigment of some myxomycetes. Mycol. Res. 1989, 92, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Řezanka, T.; Dvoráková, R.; Hanus, L.O.; Dembitsky, V.M. Enteridinines A and B from slime mold Enteridium lycoperdon. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, L.; Kalyanasundram, I. The melanin of the myxomycete Stemonitis herbatica. Acta Protozool. 1999, 38, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kaniwa, K.; Ohtsuki, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ishibashi, M. Kehokorins A-C, novel cytotoxic dibenzofurans isolated from the myxomycete Trichia favoginea var. persimilis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 1505–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, K.; Onuki, H.; Hirota, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Komiyama, K.; Sato, M.; Ishibashi, M. Tubiferal A, a backbone-rearranged triterpenoid lactone isolated from the myxomycete Tubifera dimorphotheca, possessing reversal of drug resistance activity. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 9835–9839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, H.; Saito, Y.; Sekiya, J.; Okano, Y.; Saito, M.; Nakahata, N.; Kubohara, Y.; Oshima, Y. Isolation and synthesis of a new aromatic compound, brefelamide, from Dictyostelium cellular slime molds and its inhibitory effect on the proliferation of astrocytoma cells. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 8854–8858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, Y.; Kikuchi, H.; Terui, Y.; Komiya, J.; Furukawa, K.I.; Seya, K.; Motomura, S.; Ito, A.; Oshima, Y. Novel acyl alpha-pyronoids, dictyopyrone A, B, and C, from Dictyostelium cellular slime molds. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 985–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, S.O.; Gregg, J.H. Carotenoid pigments in the cellular slime mold, Dictyostellium discoideum. Biol. Bull. 1967, 132, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidoff, F.; Korn, E. Fatty acid and phospholipid composition of cellular slime mold, Dictyostelium discoideum—Occurrence of previously undescribed fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 1963, 238, 3199–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Ochiai, H. Identification of Delta5-fatty acid desaturase from the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 265, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, C.; Ogura, T.; Narita, S.; Kondo, A.; Iwasaki, N.; Saito, T.; Usuki, T. Synthesis and SAR of 4-methyl-5-pentylbenzene-1,3-diol (MPBD), produced by Dictyostelium discoideum. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 1428–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelman, M.R.; Taylor, E.W. Further purification and characterization of slime mold myosin and slime mold actin. Biochemistry 1969, 8, 4976–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yumura, S.; Uyeda, T.Q. Myosins and cell dynamics in cellular slime molds. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2003, 224, 173–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, H.; Nakamura, K.; Kubohara, Y.; Gokan, N.; Hosaka, K.; Maeda, Y.; Oshima, Y. Dihydrodictyopyrone A and C: New members of dictyopyrone family isolated from Dictyostelium cellular slime molds. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 5905–5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Kikuchi, H.; Sasaki, H.; Iizumi, K.; Kubohara, Y.; Oshima, Y. Production of novel bispyrone metabolites in the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium giganteum induced by zinc (II) ion. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]