Circular Economy and its Comparison with 14 Other Business Sustainability Movements

Abstract

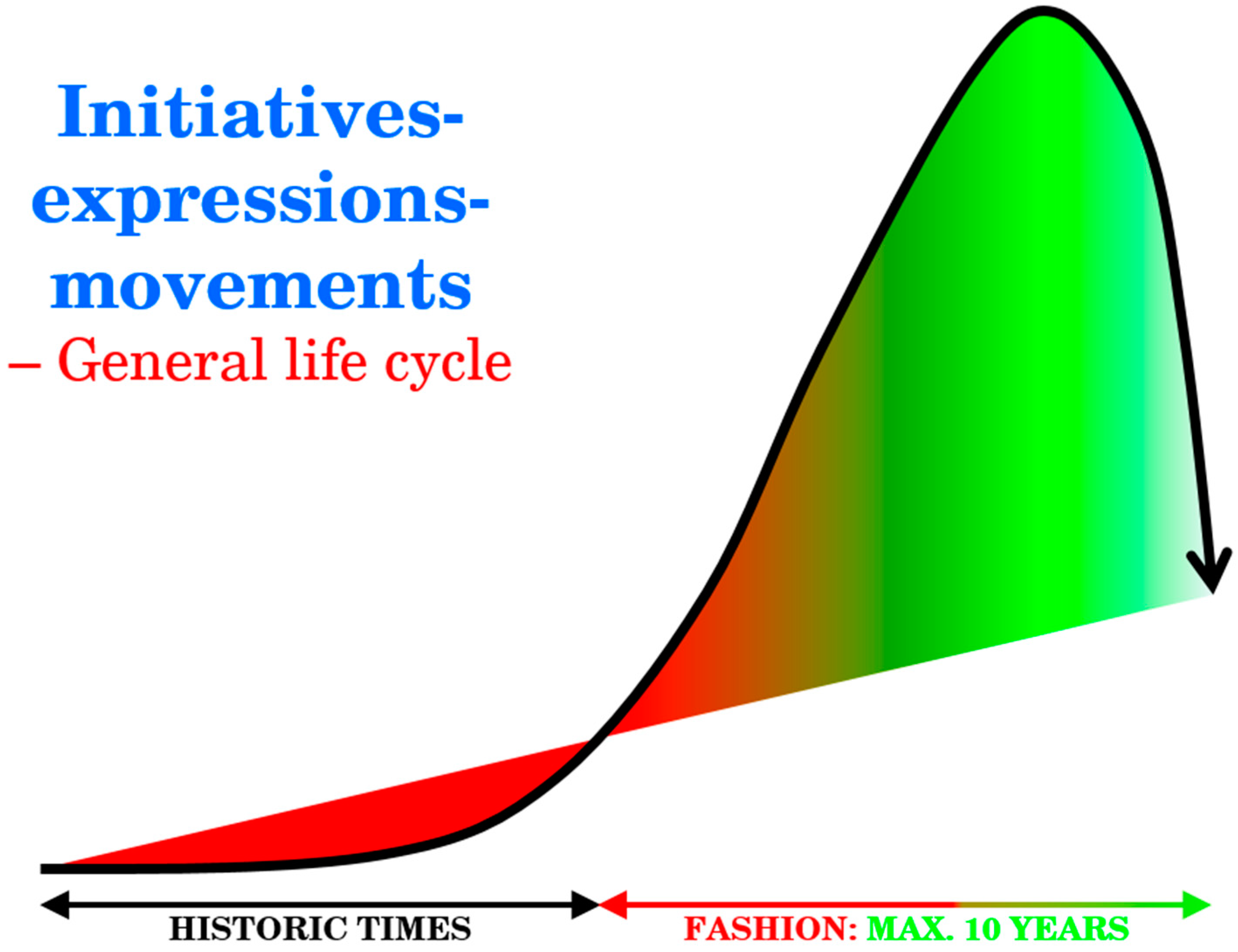

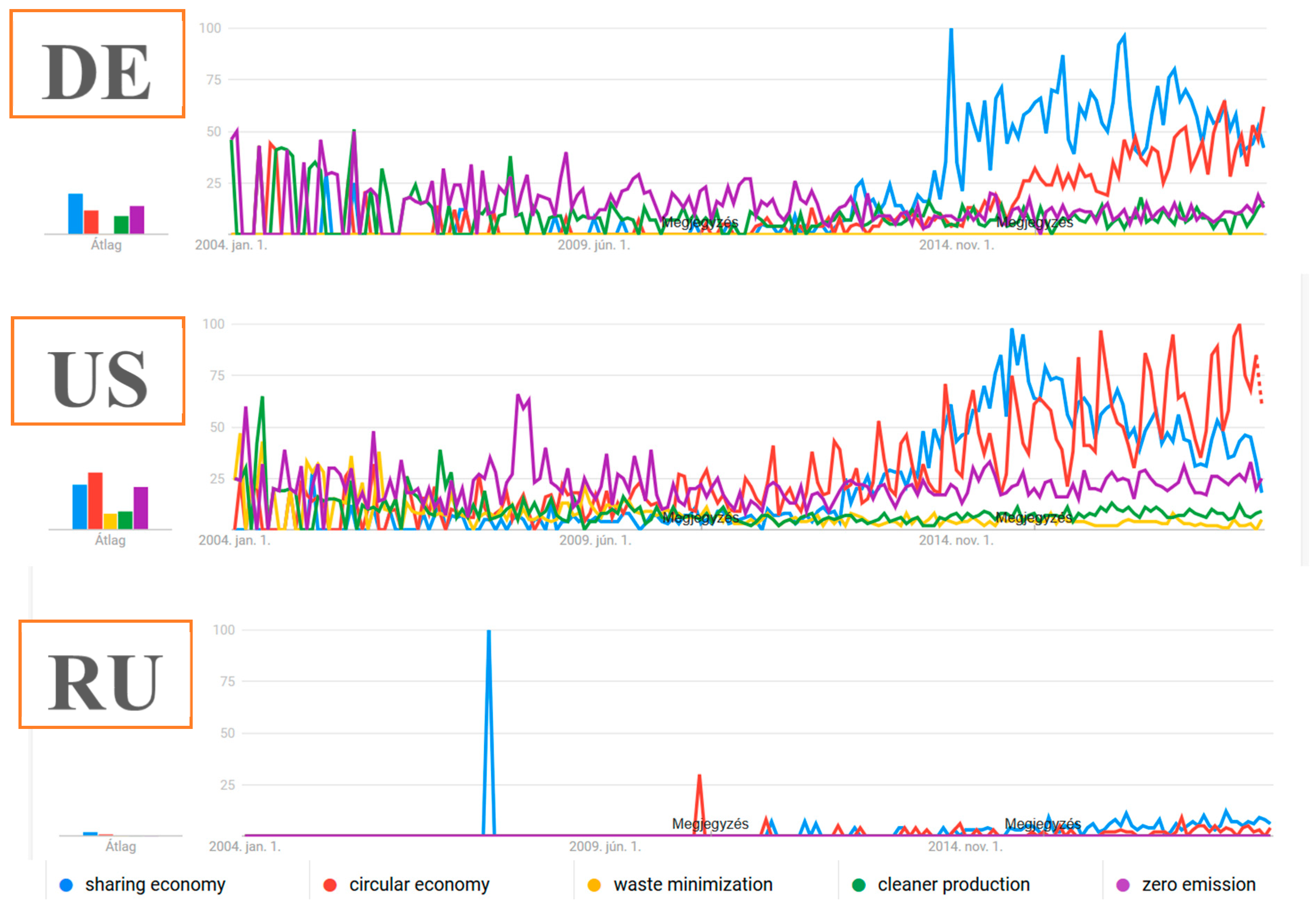

1. Introduction: Hypes, Movements, Scientific Schools

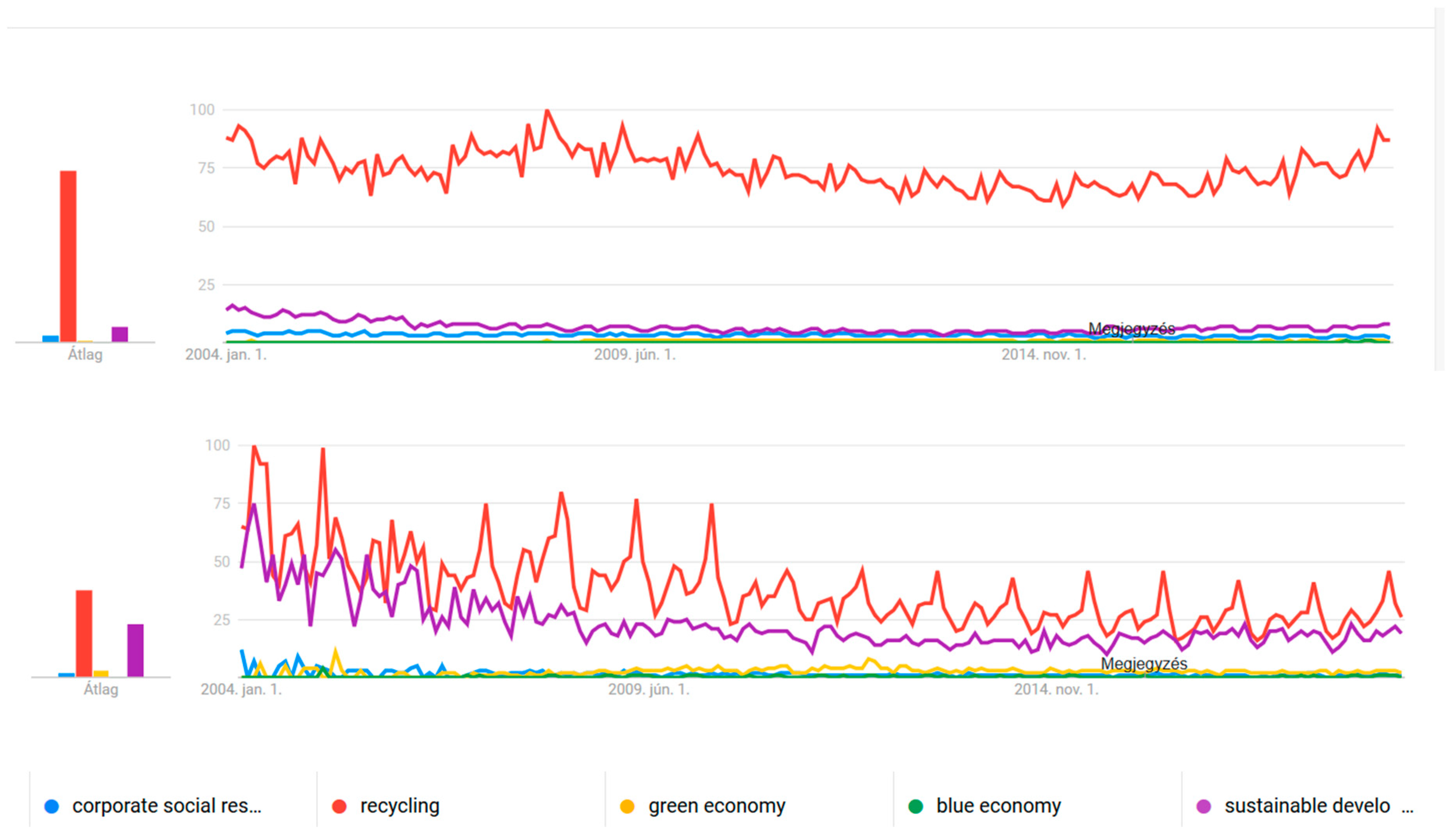

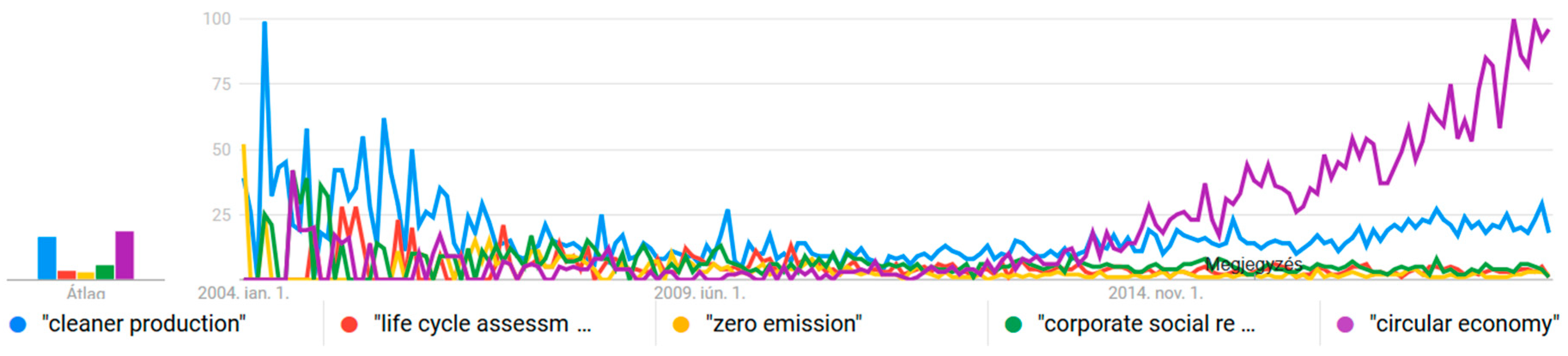

2. Dataset: A Catalogue of 15 Business Sustainability Movements

2.1. Recycling

2.2. Waste Minimization (WM)

2.3. Cleaner Production (CP)

2.4. Zero Emission

2.5. Zero Growth, Decroissanse

2.6. Green Economy (GE)

2.7. Triple-Bottom-Line, Alias 3P

2.8. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

2.9. Sustainable Consumption

2.10. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

2.11. Blue Economy

2.12. Creating Shared Value (CSV)

2.13. Industrial Ecology

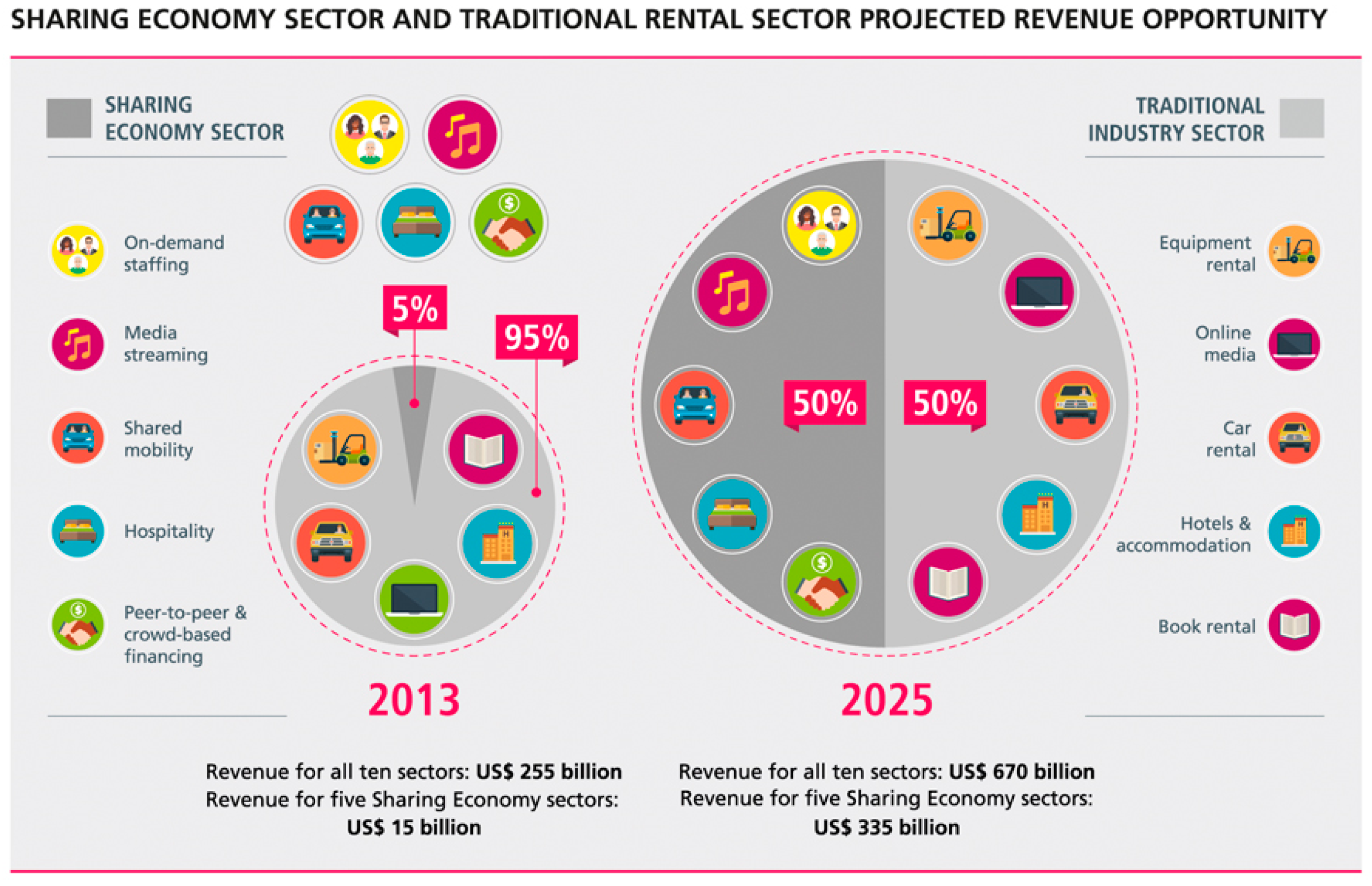

2.14. Sharing Economy

2.15. Circular Economy

3. Method: A Proposed Life Cycle

4. Analysis: The Comparative Table and Citations

5. Conclusion: Little Competition, Much Synergy

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cleveland, C.J.; Morris, C.G. Handbook of Energy: Chronologies, Top Ten Lists, and Word Clouds; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; p. 461. [Google Scholar]

- Dadd-Redalia, D. Sustaining the Earth: Choosing Consumer Products that are Safe for You, Your Family, and the Earth; Hearst Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994; p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Lienig, J.; Bruemmer, H. Recycling Requirements and Design for Environmental Compliance. Fundamentals of Electronic Systems Design; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, L. To make zero emissions technologies and strategies become a reality, the lessons learned of cleaner production dissemination have to be known. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1205–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, E.; Linke, M.; Tobler, M.; Beke, B.V. EU COST Action 628: Life cycle assessment (LCA) of textile products, eco-efficiency and definition of best available technology (BAT) of textile processing. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.J. The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, G.M.; Bardhi, F. The Sharing Economy Isn’t About Sharing at All. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 28, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gravitis, J. Zero techniques and systems—ZETS strength and weakness. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I. The Profitability of Residential Photovoltaic Systems. A New Scheme of Subsidies Based on the Price of CO2 in a Developed PV Market. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassanelli, C.; Rosa, P.; Rocca, R.; Terzi, S. Circular economy performance assessment methods: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graedel, T.E.; Reck, B.K.; Ciacci, L.; Passarini, F. On the Spatial Dimension of the Circular Economy. Resources 2019, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselev, A.; Magaril, E.; Magaril, R.; Panepinto, D.; Ravina, M.; Zanetti, M.C. Towards Circular Economy: Evaluation of Sewage Sludge Biogas Solutions. Resources 2019, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. How do scholars approach the circular economy? A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 178, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price Waterhouse Coopers (PWC). The Sharing Economy—Sizing the Revenue Opportunity; PricewaterhouseCoopers: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Waste Framework Directive, or Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2008.

- Ojovan, M.I.; Lee, W.E. An Introduction to Nuclear Waste Immobilisation, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, P.E.; Feng, L.G.H. Risks of Hazardous Wastes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P.R. The Kroll Institute for Extractive Metallurgy; KIEM: Golden, CO, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J.S.; Benforado, D.M. Life Cycle Approach to Effective Waste Minimization. JAPCA 1987, 37, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G. The Truly Responsible Enterprise—About Unsustainable Development, the Tools of CORP-ORATE Social Responsibility (CSR) and the Deeper, Strategic Approach; KÖVET: Budapest, Hungary, 2007; p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer, H.; Ulgiati, S. Less bad is not good enough: Approaching zero emissions techniques and systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehr, R. Towards a sustainable society: United Nations University’s Zero Emissions Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.; Porche, I.R.; Kulick, J. Driving Emissions to Zero—Are the Benefits of California’s Zero Emission Vehicle Program Worth the Costs? 2002. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1578.html (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Daly, H.E. Steady-State Economic; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, H.E. Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Latouche, S. Le Pari de la Décroissance; Fayard: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication. 2011. Available online: www.unep.org/greeneconomy (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Kahle, L.R.; Gurel-Atay, E. Communicating Sustainability for the Green Economy; M.E. Sharpe: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.W.; Barbier, E.B.; Markandya, A.; Barbier, E. Blueprint for a Green Economy; Earthscan: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Ministry of the Environment [NME]. Oslo Roundtable on Sustainable Production and Consumption; Norwegian Ministry of the Environment: Oslo, Norway, 1994.

- EC. Communication from the Commission Concerning Corporate Social Responsibility: A Business Contribution to Sustainable Development; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- EC. ABC of the Main Instruments of Corporate Social Responsibility; European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment and Social Affairs: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- EC. Communication from the Commission Concerning Corporate Social Responsibility: Implementing the Partnership for Growth and Jobs: Making Europe a Pole of Excellence on CSR; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- Watts, P.; Holme, L. Meeting Changing Expectations—Corporate Social Responsibility; WBCSD Report: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pauli, G. The Blue Economy—10 Years, 100 Innovations, 100 Million Jobs; Paradigm Publications: Brookline, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. How to reinvent the capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Beschorner, T. Creating Shared Value: The One-Trick Pony Approach—A Comment on Michael Porter and Mark Kramer. Bus. Ethics J. Rev. 2013, 17, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, M.A. The Sharing Economy: Why People Participate in Collaborative Consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, L. Review—The Sharing Economy. Financial Times. 22 June 2016. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/f560e5ee-36e8-11e6-a780-b48ed7b6126f (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Boulding, K.E. The Economies of the Coming Spaceship Earth; University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries: Boulder, CO, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Clean Production Strategies Developing Preventive Environmental Management in the Industrial Economy; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, W.F. Two Lectures on the Checks to Population; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1833. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP-UNIDO: Resource Efficient and Cleaner Production (RECP). 1992. Available online: https://www.unido.org/our-focus/safeguarding-environment/resource-efficient-and-low-carbon-industrial-production/resource-efficient-and-cleaner-production-recp (accessed on 21 July 2019).

- USA Senate. Federal Low-Emission Vehicle Procurement Act: Joint Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Energy, Natural Resources, and the Environment. In Proceedings of the Ninety-first Congress, Second Session, Washington, DC, USA, 27–29 January 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.; Donatella Meadows, J.; Randers, W.; Behrens, W., III. The Limits to Growth—A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Vigon, B.W. Life-Cycle Assessment: Inventory Guidelines and Principles; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Goodpaster, K.E.; Matthews, J.B., Jr. Can a Corporation Have a Conscience? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1982, 60, 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Frosch, R.A.; Gallopoulos, N.E. Strategies for Manufacturing—Wastes from one industrial process can serve as the raw material for another, thereby reducing the impact on the environment. Sci. Am. 1989, 261, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkler, Y. Coase’s Penguin, or, Linux and The Nature of the Firm. Yale Law J. 2002, 112, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessig, L. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy; Penguin Press: London, UK, 2008; p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Reike, D.; Vermeulen, W.J.V.; Witjes, S. The circular economy: New or Refurbished as CE 3.0? Exploring Controversies in the Conceptualization of the Circular Economy through a Focus on History and Resource Value Retention Options. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaehn, F. Sustainable Operations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 253, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, T.; Hartung, K.; Hetesi, Z.S. Termelőüzem ökológiai szempontú tervezése. Közgazdasági Szle. 2019, 66, 863–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellinia, P.; Cialanib, C.; Ulgiatic, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarassy, C.; Neubauer, E.; Mansur, H.; Tangl, A.; Oláh, J.; Popp, J. The main transition management issues and the effects of environmental accounting on financial performance—With focus on cement industry. Adm. Manag. Public 2018, 31, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, B.; Mallinguh, E.; Fogarassy, C. Designing Business Solutions for Plastic Waste Management to Enhance Circular Transitions in Kenya. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| I. | II. | III. | IV. | V. | VI. | VII. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Movement | First sci. mention | Top year, G. &G.schol. hits | Bottom year, G.& G.s. hits | Google & G. sc. hits 2019 | High as movement | Sci Dir hits years on top | |

| 1. | Recycling | Platon, 4th century B.C. | 04-2008: 100 02-2004: 100 | 02-2015: 58 07-2017: 18 | 06-2019: 85 06-2019: 26 | Since WW2: 1939–1945 | 429,476 80 |

| 2. | Waste minimization | P.R. Taylor, 1974 1 [19] | 01-2004: 1 02-2004: 6 | 01-2004: 1 01-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 1 | 1970s 1980s | 4541 10 |

| 3. | Cleaner Production (CP) | UNEP-UNIDO, 1992 [48] | 02-2004: 1 04-2004: 12 | 01-2004: 1 03-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 7 | NCPCs & NCPPs 1994 | 25,567 22 |

| 4. | Zero emission | US Congress, 1970 [49] | 09-2009: 1 01-2004: 13 | 01-2004: 1 04-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 1 | ZERI 2004 | 11,849 12 |

| 5. | Zero growth, decroissanse | Meadows, 1972 [50] | 04-2004: 1 04-2005: 7 | 01-2004: 1 02-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 1 | OECD 1985 | 3565 8 |

| 6. | Green economy | Pearce, 1989 [30] | 05-2008: 1 04-2004: 11 | 03-2004: 0 01-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 2 | ICC 2012 | 2737 8 |

| 7. | Triple-bottom-line, alias 3P 2 | Elkington, 1994 [31] | 02-2004: 1 09-2004: 9 | 01-2004: 1 01-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 1 | 2000s: Co. sust. Reports | 3515 9 |

| 8. | Life Cycle Assessment | Vigon, 1994 [51] | 01-2004: 1 02-2007: 7 | 02-2004: 0 01-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 1 | US-EPA 2010 | 23,420 11 |

| 9. | Sustainable consumption | Oslo Symposium, 1994 [33] | 01-2004: 1 01-2004: 12 | 01-2004: 13 05-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 1 | UN 2000s | 3620 7 |

| 10. | Corporate Soc. Responsibility | Goodpaster-Matth., 1982 [52] | 04-2004: 5 03-2004: 7 | 07-2006: 2 02-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 2 06-2019: 1 | 2000s: Co. CSR reports | 9842 8 |

| 11. | Blue economy | G. Pauli, 2010 [38] | 11-2018: 1 06-2006: 2 | 01-2004: 1 01-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 1 | WWF 2018 | 321 3 |

| 12. | Creating shared value (CSV) | M. Porter, 2011 [39] | 06-2004: 1 11-2007: 1 | 01-2004: 0 01-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 0 | EC 2010s | 873 5 |

| 13. | Industrial ecology | Frosch-Gallo-poulos, 1989 [53] | 05-2004: 1 05-2005: 23 | 01-2004: 1 01-2013: 1 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 1 | 2000s | 5497 7 |

| 14. | Sharing economy | Benkler, 2002 [54], Lessig, 2008 [55] | 10-2014: 1 07-2007: 1 | 01-2004: 0 01-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 1 | Last 5 years | 1552 4 |

| 15. | CIRCULAR ECONOMY | Boulding, 1965 [44] Pearce, 1989 [30] Jackson, 1993 [45] | 02-2019: 2 02-2019: 23 | 03-2004: 0 01-2004: 0 | 06-2019: 1 06-2019: 23 | Last 3 years | 5918 4 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tóth, G. Circular Economy and its Comparison with 14 Other Business Sustainability Movements. Resources 2019, 8, 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8040159

Tóth G. Circular Economy and its Comparison with 14 Other Business Sustainability Movements. Resources. 2019; 8(4):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8040159

Chicago/Turabian StyleTóth, Gergely. 2019. "Circular Economy and its Comparison with 14 Other Business Sustainability Movements" Resources 8, no. 4: 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8040159

APA StyleTóth, G. (2019). Circular Economy and its Comparison with 14 Other Business Sustainability Movements. Resources, 8(4), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8040159