Social Life-Cycle Assessment of a Piece of Jewellery. Emphasis on the Local Community

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Goal and Scope Definition

2.2. Life-Cycle Inventory (LCI)

- A company questionnaire compiled by the owners of the goldsmith;

- A Confederation of the Nation of Craft and Small and Medium Enterprises (CNA) questionnaire compiled by a representative of a local confederation;

- A member of the local community questionnaire compiled by the director of a local museum: The Museum of Fossils and Ambers, S. Valentino in Abruzzo Cit., Italy.

2.3. Life-Cycle Impact Assessment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of Subcategory Assessment Method (SAM) for the Local Community

3.2. Social Performance of “Stregonia” on Local Community

4. Conclusions

- The goldsmith is committed to producing the piece of jewellery by respecting the environment: by making use of the best available clean technologies, by using energy, materials and natural resources efficiently, and by consuming water resources responsibly and reasonably.

- The goldsmith cares for both consumers and members of the local community in general. The care for the consumer is not only a value, but a daily practice that has its foundation in a sense of responsibility that goes far beyond commercial objectives. This responsibility is accomplished through continuous customer loyalty, by guaranteeing product quality, consumer privacy and transparency. Furthermore, the goldsmith pays constant attention to the communities in which it operates. This commitment is demonstrated through the multiple activities of cultural involvement, through all the initiatives and meetings activated for the local community in the form of exhibitions, concerts, conferences or book presentations.

- The goldsmith protects and enhances cultural heritage and local traditions. The goldsmith carries out historical, artistic and cultural studies and he is a collector of ancient medals, books, and fossils; all this constitutes a broad cultural background that reflects on the added value that they can offer to the customer.

- the evaluation highlights that the product does not have a value to itself (in terms of materials and manufacturing) but generates shared value for the members of the local community;

- the product, through its history handed down over generations, promotes artisan craft activities and related cultural and landscape activities;

- the product supports the continuation of historical commercial activities;

- SAM highlights the positive impacts of products at level “A”, whose achievement is only possible through the performance of proactive activities;

- SAM defines a performance reference point for each indicator analysed, which is based on the current international and national legislation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jamal, A.; Goode, M. Consumers’ product evaluation: A study of the primary evaluative criteria in the precious jewellery market in the UK. J. Consum. Behav. 2011, 1, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krijger, M. CBI Trade Statistics for Jewellery’, Global Intelligence Alliance/Centre for the Promotion of Imports from Developing Countries (CBI); Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Hague, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, F. Sintering and additive manufacturing: Additive manufacturing and the new paradigm for the jewellery manufacturer. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2016, 1, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. Social Drivers of Sustainable Development; United Nations Research Institute for Social Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- D’Eusanio, M.; Zamagni, A.; Petti, L. Social Sustainability and Supply Chain Management: Methods and tools. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannouf, M.; Assefa, G. Subcategory assessment method for social life cycle assessment: A case study of high-density polyethylene production in Alberta, Canada. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP/SETAC. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC). Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products. Life-Cycle Initiative; United Nations Environment Programme and Society for Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Parent, J.; Cucuzzella, C.; Revéret, J.P. Impact assessment in SLCA: Sorting the sLCIA methods according to their outcomes. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, S.R.; Parent, J.; Beaulieu, L.; Revéret, J.P. A literature review of type I SLCA-making the logic underlying methodological choices explicit. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macombe, C.; Leskinen, P.; Feschet, P.; Antikainen, R. Social life cycle assessment of biodiesel production at three levels: A literature review and development needs. J. Clean. Product. 2013, 52, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, L.; Serreli, M.; Di Cesare, S. Systematic literature review in social life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamagni, A.; Amerighi, O.; Buttol, P. Strenghts or bias in social LCA? Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2011, 16, 596–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureau, S.; Mazijn, B.; Garrido, S.R.; Achten, W.M.J. Social life cycle assessment framework: Review of criteria and indicators proposed to assess social and socioeconomic impacts. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 904–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Blanco, J.; Lehmann, A.; Chang, Y.J.; Finkbeiner, M. Social organisational LCA (SOLCA)—A new approach for implementing social LCA. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 1586–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Eusanio, M.; Serreli, M.; Zamagni, A.; Petti, L. Assessment of social dimension of a jar of honey: A methodological outline. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, A.I.; Iofrida, N.; Strano, A.; Falcone, G.; Gulisano, G. Social Life Cycle Assessment and Participatory Approaches: A mathoedological proposal Applied to Citrus Farming in Southern Italy. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2015, 11, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settembre Blundo, D.; Ferrari, A.M.; del Hoyo, A.F.; Riccardi, M.P.; Muina, E.G. Improving sustainable cultural heritage restoration work through life cycle assessment based model. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 32, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibánez-Forés, V.; Bovea, M.D.; Coutinho-Nóbrega, C.; de Medeiros, H.R. Assessing the social perfomrnace of municipal solid waste management systems in developing countries: Proposal of indicators and a case study. Ecol. Indicat. 2019, 98, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, C.; Brekke, A.; Modahl, I.S. Testing environmental and social indicators for biorefineries: Bioethanol and biochemical production. Int. J. Life Cycle Access. 2018, 23, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardvisson, R.; Hildenbrand, J.; Baumann, H.; Nazmul Islam, K.M.; Parsmo, R. A method for human health impact assessment in social LCA: Lessons from three case studies. Int. J. Life Cycle Access. 2018, 23, 690–699. [Google Scholar]

- Yi Teah, H.; Onuki, M. Support Phosphorus Recycling Policy with Social Life Cycle Assessment: A case of Japan. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papong, S.; Itsubo, N.; Ono, Y.; Malakul, P. Development of Social Intensity Database Using Asian International Input-Output Table for Social Life Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, L.; Sala, S. Social impact assessment in the mining sector: Review and comparison of indicators frameworks. Resour. Policy 2018, 57, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez Ramirez, P.K.; Petti, L.; Ugaya, C.M.L. Subcategory assessment method (SAM) for S-LCA: Stakeholder “worker” and “consumer”. In What Is Sustainable Technology? the Role of Life Cycle-based Methods in Addressing the Challenges of Sustainability Assessment of Technologies; Barberio, G., Rigamonti, L., Zamagni, A., Eds.; ENEA Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC). The Methodological Sheets of Sub-Categories of Impact in a Social Life Cycle Assessment; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya; SETAC: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Blanco, J.; Lehmann, A.; Munoz, P.; Anton, A.; Traverso, M.; Rieradevall, J.; Finkbeiner, M. Application challenges for the Social Life Cycle Assessment of fertilizers within life cycle sustainability assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 69, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit-Norris, C.; Cavan, D.A.; Norris, G. Identifying Social Impacts in Product Supply Chains: Overview and Application of the Social Hotspot Database. Sustainability 2014, 4, 1946–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzid, A.; Padilla, M. Analysis of social performance of the industrial tomatoes food chain in Algeria. N. Medit. 2014, 1, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Agyekum, E.O.; Fortuin, K.P.J.; van der Harst, E. Environmental and social life cycle assessment of bamboo bicycles frames made in Ghana. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, S.; Silveri, F.; Sala, S.; Petti, P. Positive impacts in social life cycle assessment: State of the art and way forward. Int. J. Life Cycle Access. 2018, 23, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guion, L.A.; Diehl, D.C.; McDonald, D. Triangulation: Establishing the Validity of Qualitative Studies; University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, C.; Norris, G.A.; Valdivia, S.; Ciroth, A.; Moberg, A.; Bos, U.; Prakash, S.; Ugaya, C.; Beck, T. The guidelines for social life cycle assessment of product: Just in time! Int. J. Life Cycle Access. 2010, 15, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franze, J.; Ciroth, A. A comparison of cut roses from Ecuator and the Netherlands. Int. J. Life Cycle Access. 2011, 16, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, L.; Sanchez Ramirez, P.K.; Traverso, M.; Ugaya, C.M.L. An Italian tomato ”Cuore di Bue” case study: Challenges and benefits using subcategory assessment method for social life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traverso, M.; Asdrubali, G.; Francia, A.; Finkbeiner, M. Towards life cycle sustainability assessment: An implementation to photovoltaic modules. Int. J. Life Cycle Access. 2012, 17, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foolmaun, R.K.; Ramjeeawon, T. Comparative life cycle assessment and social life cycle assessment of used poluthylene terephthalate (PET) bottles in Mauritius. Int. J. Life Cycle Access. 2013, 18, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparcana, S.; Salhofer, S. Application of a methodology for the social life cycle assessment of recycling systems in low income countries: Three Peruvian case studies. Int. J. Life Cycle Access. 2013, 18, 1116–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, S.; Björklund, A.; Ekener Petersen, E. Social impact assessment of informal recycling of electronic ICT waste in Pakistan using UNEP SETAC guidelines. Res. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Lenzen, M.; Geschke, A. Triple Bottom Line Study of a Lignocellulosic Biofuel Industry. GCB Bioenergy 2015, 8, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessière, J. Local development and heritage: Traditional food and cuisines tourist attraction in rural areas. Eur. Soc. Rural Soc. 1998, 38, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas, 3rd ed.; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Input | Process | Output |

|---|---|---|

| “Stellaria” Stone; Cabochonatrice; Energy; Water. | Cutting “Pietra Stellaria”. | The heart-shape of “Stellaria” stone; Wastewater. |

| Silver and copper; Casting oven; Energy. | Fusion of silver with a small amount of copper. | Alloy. |

| Alloy; Tools to shape the alloy. | Transformation of the alloy. | Silver/copper slab. |

| Silver/copper slab; Non-toxic acid | Cooling of silver/copper slab. | Cooled silver/copper slab. |

| Slab; die plate; Energy. | Processing of the slab in the wire drawing machine. | Flat slab; Slab residues that are also recovered from the used gloves. |

| “Stellaria” stone; Silver slab; Caliper and file. | Shaping of the “Stellaria” stone with the silver slab. | “Stellaria” stone shaped in silver. |

| Shaped “Stellaria” stone; Laminated slab; Welding machine; Energy. | Welding of the pendant on the laminated slab. | Frame of “Stregonia” pendant. |

| Thick slab; Frame of “Stregonia” pendant; Welding machine; Energy. | Welding of the pendant bails made with thicker slab. | Pendant bails. |

| Pendant bails; Milling machine. | Cutting of the shape of the “Stellar stone” with a cutter, production of the indentation. | Jagged “Stregonia” pendant. |

| “Stregonia” pendant; Gray rubber. | Finishing of the pendant with a rubber. | Finished “Stregonia” pendant. |

| “Stregonia” pendant; Polishing paste; Energy. | Polishing of the “Stregonia” pendant with a brush and a silver paste. | Polished “Stregonia” pendant. |

| Subcategories | Sources | Description | Type of Data Collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to Immaterial Resources | UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets [25] | To evaluate the extent to which the company organisation provides and improves local community access to intangible resources. | 1 question |

| Access to Material Resources | UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets [25] | To assess the extent to which the company organisation provides and improves the local community’s access to material resources such as water, minerals and resources or infrastructure such as school roads, etc. | 4 questions |

| Delocalisation and Migration | UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets [25] | To evaluate if the contribution of the organisations towards delocalisation, migration within local communities and the treatment of populations is adequate. | Interviews |

| Cultural Heritage | UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets [25] | To recognise the local cultural heritage (i.e., language, social and religious practices, knowledge and traditional craftsmanship) and to promote the cultural development of the members of local community. | 7 questions |

| Safe and Healthy Living Conditions | UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets [25] | To promote the general safety conditions of the community in terms of use of hazardous materials and pollution emissions. | 4 questions |

| Respect of Indigenous Rights | UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets [25] | To highlight any conflicts with native inhabitants and respect for their rights. | Interviews |

| Community Engagement | UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets [25] | To involve the community in the development and implementation of business policies and decisions. | 6 questions |

| Local Employment | UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets [25] | To provide income and training activities to community members in terms of technical and transferable skills. | 2 questions |

| Secure Living Conditions | UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets [25] | To contribute to the security of local communities in respect to the private security personnel status. | 2 questions |

| Territory | Authors 1 | To promote artistic-cultural tourism linked to the analysed geographical territory. | 2 questions |

| Corporate Behavior | Proactive | Basic Requirement (BR) | Not Satisfactory BR (Negative Context) | Not Satisfactory BR (Positive Context) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels Scale | A | B | C | D |

| Scores Scale | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Local Community Subcategories | Social Indicators | Unit of Measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to Immaterial Resources |

|

| Evidence the promotion of community services (educations, information sharing). |

| Access to Material Resources |

|

| No evidence of environmental management system in the company and formal environmental risk assessment. |

| Community Engagement |

|

| The organisation actively organises and joins in events of local community (cultural exhibitions, concerts, book presentations). |

| Delocalisation and Migration |

|

| No evidence of resettlement caused by the organisation. |

| Cultural Heritage |

|

| Evidence of the promotion of cultural historical and artistic events to considers activities of cultural heritage preservation. |

| Safe and Healthy Living Conditions |

|

| Absence of conflict with the local community and presence of safe system within the surroundings the shop. |

| Respect of Indigenous Rights |

|

| Communities and regions were engaged by similar activities and there is no conflict with the local community. |

| Local Employment |

|

| When uses local suppliers. |

| Secure Living Conditions |

|

| The organisation does not reveal any conflicts or problems with the local community proven by the absence of judicial appeals to the organisation. |

| Territory |

|

| The organisation is engaged in programs and activities in order to protect the local ecosystem by supporting educational and cultural events. |

| No. | Submitted Questions | Answers |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Does the goldsmith have policies aimed at protecting cultural heritage? | No |

| 2 | Does the goldsmith finance, support and promote cultural or artistic events that are an expression of local cultural heritage? | Yes |

| 3 | If yes, how? | The company supports the community through the promotion and organisation of exhibitions of natural stones, local artists and typical products. |

| 4 | Does the goldsmith provide programs that allow the inclusion of cultural heritage in the selection of products? | Yes |

| 5 | If yes, name a few. | The choice of traditional stones and traditional design of the product. |

| 6 | Does the goldsmith implement policies to defend cultural heritage? | No |

| 7 | Does the goldsmith carry out studies, historical, artistic and cultural studies? | Yes |

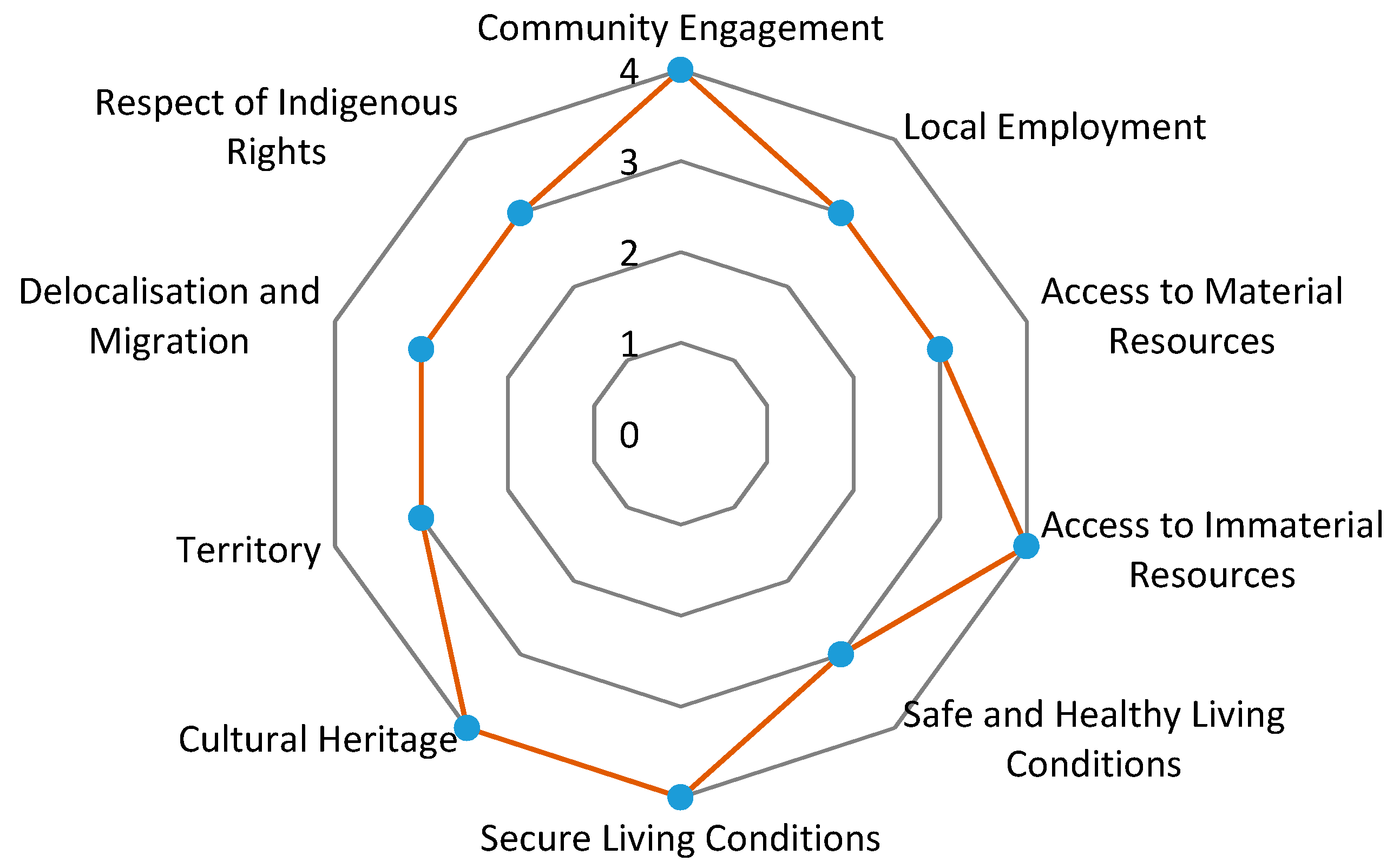

| Subcategories | Level Scale |

|---|---|

| Community Engagement | A |

| Local Employment | B |

| Access to Material Resources | B |

| Access to Immaterial Resources | A |

| Safe and Healthy Living Conditions | B |

| Secure Living Conditions | A |

| Cultural Heritage | A |

| Territory | B |

| Delocalisation and Migration | B |

| Respect of Indigenous rights | B |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Eusanio, M.; Serreli, M.; Petti, L. Social Life-Cycle Assessment of a Piece of Jewellery. Emphasis on the Local Community. Resources 2019, 8, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8040158

D’Eusanio M, Serreli M, Petti L. Social Life-Cycle Assessment of a Piece of Jewellery. Emphasis on the Local Community. Resources. 2019; 8(4):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8040158

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Eusanio, Manuela, Monica Serreli, and Luigia Petti. 2019. "Social Life-Cycle Assessment of a Piece of Jewellery. Emphasis on the Local Community" Resources 8, no. 4: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8040158

APA StyleD’Eusanio, M., Serreli, M., & Petti, L. (2019). Social Life-Cycle Assessment of a Piece of Jewellery. Emphasis on the Local Community. Resources, 8(4), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8040158