Leveraging a Systems Approach for Immigrant Integration: Fostering Agile, Resilient, and Sustainable Organizational Governance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- –

- Skilled Migrants/Economic Immigrants: Individuals chosen for their education, skills, and potential economic contributions.

- –

- Family Reunification Migrants: Individuals joining family members already established in the host country.

- –

- Refugees and Asylum Seekers: Those seeking protection from persecution or conflict, often facing unique integration challenges.

- –

- Temporary Migrant Workers: Including seasonal or contract-based workers.

2. Theoretical Foundations: A Systems Perspective on Immigrant Integration

- –

- Holism and Emergence: This model argues that immigrant integration is not merely the sum of individual efforts but an emergent property of the interactions among various organizational subsystems. Successful integration arises from the synergistic functioning of these parts, leading to outcomes (e.g., enhanced innovation, improved organizational agility) that cannot be attributed to any single component in isolation.

- –

- Interdependence and Interconnectedness: Each subsystem within the model (e.g., Needs Assessment, Organizational Culture, Human Resource Management, Leadership and Communication, Training and Development, Job Transitions) is inextricably linked to and influences the others. Changes in one area inevitably propagate throughout the system, highlighting the need for coordinated and integrated interventions. For instance, effective needs assessment directly impacts the relevance of training programs and the success of job transitions.

- –

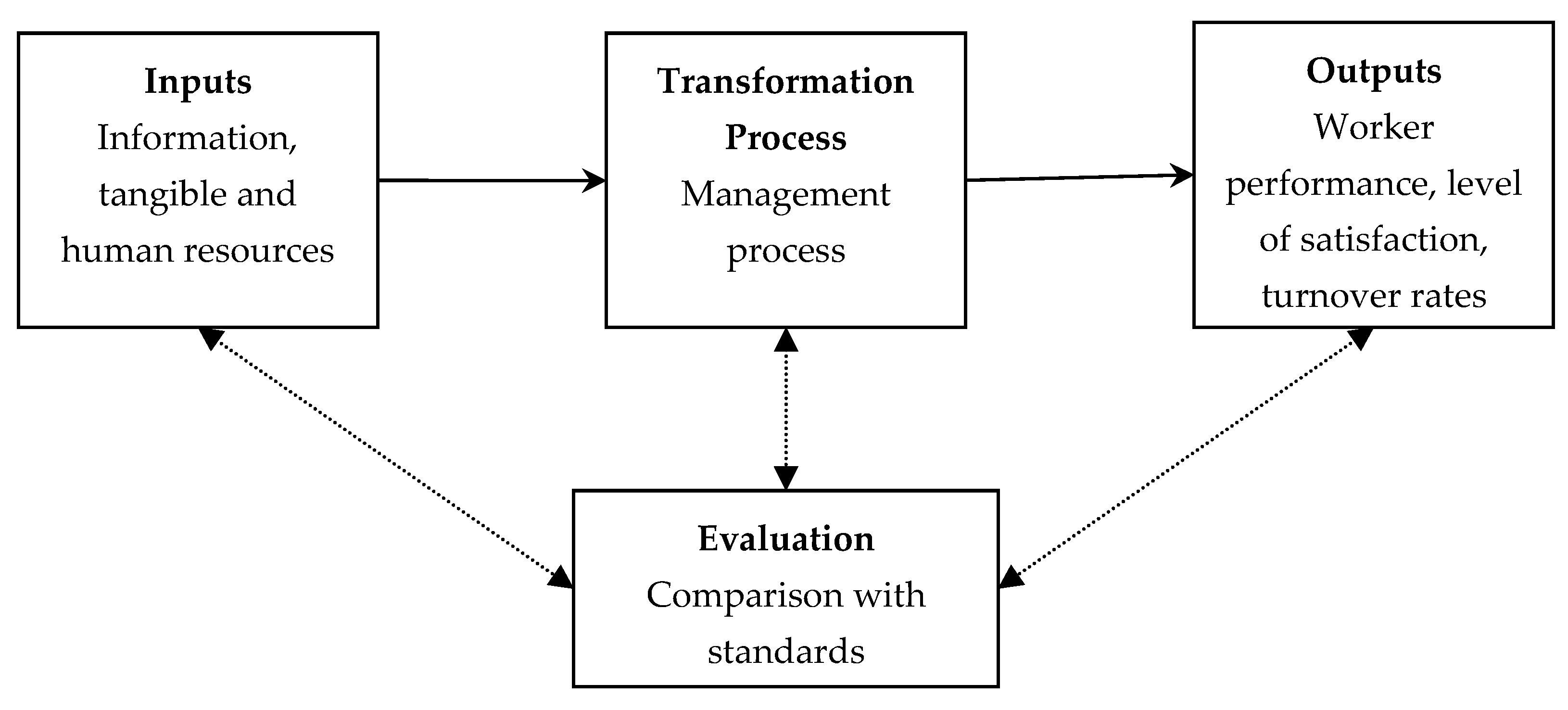

- Feedback Loops: Systems theory highlights the importance of feedback for adaptation and learning. The model includes continuous monitoring and evaluation, which helps organizations gather feedback on integration efforts and make ongoing improvements. This ability to adapt is key for creating flexible and resilient governance, especially as immigrant needs and organizational dynamics change.

- –

- Boundaries and Environment: While systems have clear boundaries, organizations are open systems that constantly exchange resources and information with their external environment. This includes interacting with immigrant communities, government policies, labor markets, and public opinions. A systems approach recognizes these external factors and their effect on internal integration processes.

- –

- Equifinality and Multifinality: Systems theory suggests that similar outcomes can be reached from different starting points (equifinality), and that the same starting point can lead to different outcomes (multifinality). This means that integration strategies should be flexible and adapted to each context, rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach.

3. Methodological Approach and Theoretical Foundations

3.1. Methodological Approach

- 1.

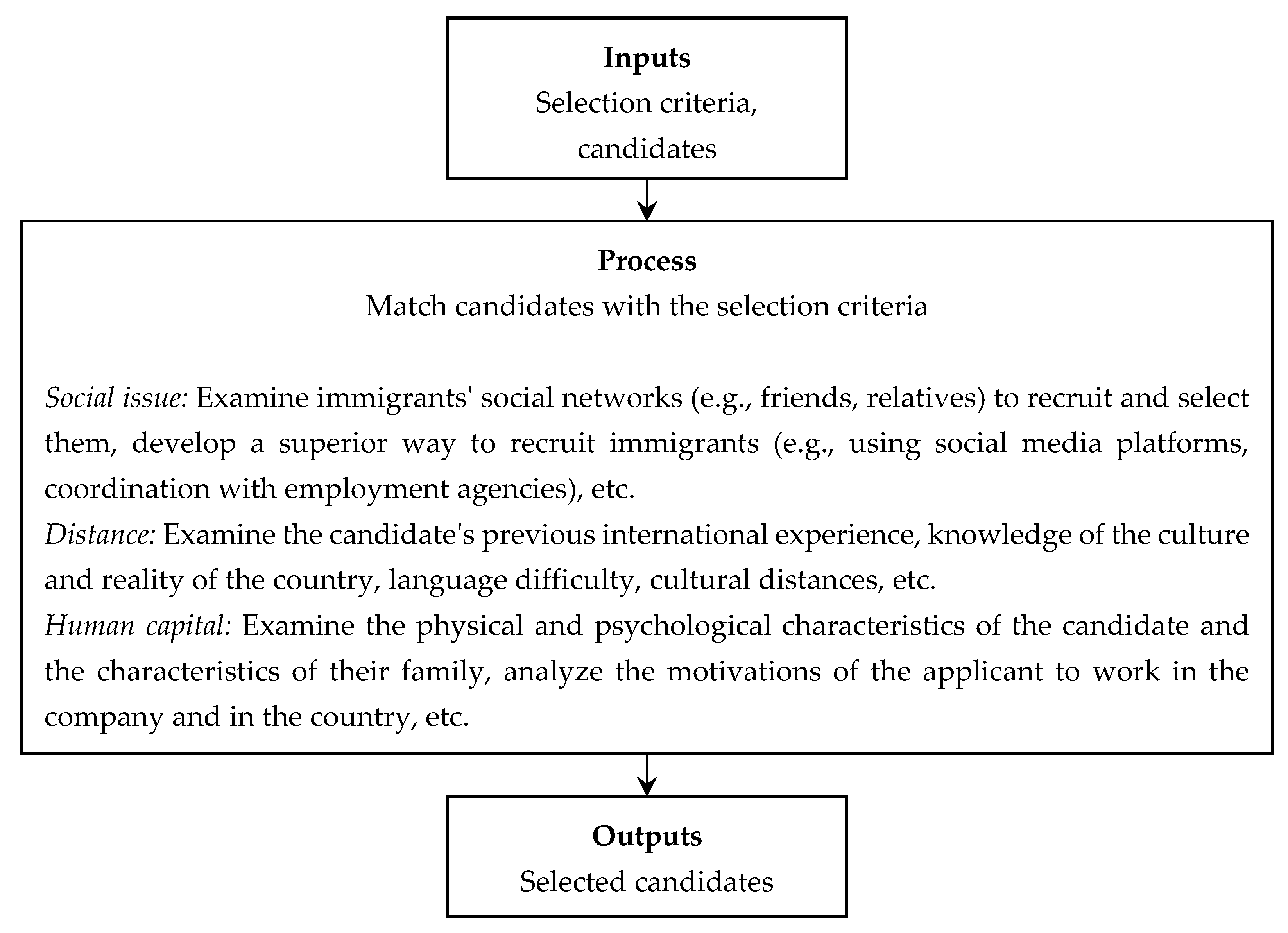

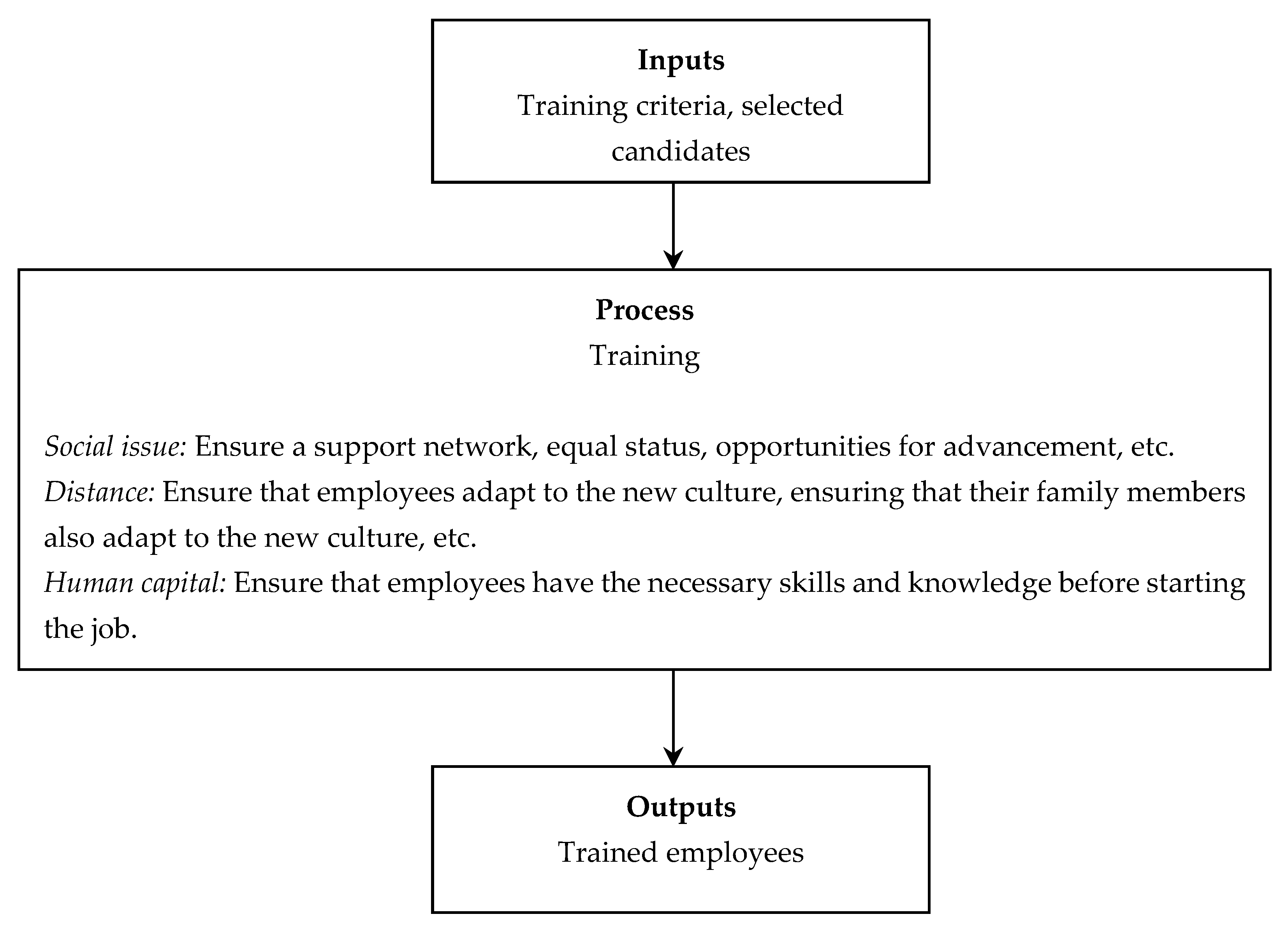

- Precise Definition of Constructs: Each of the six core subsystems (Needs assessment, Selection, Training, Start of the work, Development, End of the work) and the overarching concepts (e.g., Social issue, Distance, Human capital) have been carefully defined based on the established literature in organizational studies, human resource management, and migration studies. These definitions aim for clarity and consistency throughout the model.

- 2.

- Logical Development of Propositions between Constructs: The paper posits specific relationships between the six interdependent subsystems. For example, it is proposed that effective ‘Onboarding and Initial Integration’ (Subsystem 3) positively influences ‘Skills Development and Career Progression’ (Subsystem 4) and ‘Performance Management and Cultural Adaptation’ (Subsystem 5). These propositions are embedded in the description of how the subsystems interact and form a cohesive system. Feedback loops are also proposed, suggesting that outcomes from later subsystems inform earlier ones (e.g., insights from ‘End of Work’ can refine ‘Needs Assessment’).

- 3.

- Reasoned Justification of these Relationships: The justification for the proposed relationships between subsystems is drawn from established theories (e.g., systems theory’s emphasis on interdependence, social learning theory for onboarding, human capital theory for skills development) and extant empirical findings in related fields. For each subsystem and its links to others, the paper outlines the rationale for its inclusion and its expected impact on the overall system’s effectiveness in integrating immigrant talent.

- 4.

- Precise Delimitation of the Scope: The scope of this conceptual model is primarily organizational governance of immigrant workforce integration within formal employing organizations, particularly those operating in contexts with significant immigrant populations. While the principles may have broader applicability, the model is specifically tailored to the workplace context. It focuses on the organizational processes and structures that can be leveraged, acknowledging that external societal factors (e.g., national immigration policies, social services) also play a role but are considered environmental inputs or influences on the organizational system rather than core components of this particular model.

3.2. Theoretical Foundations

- 1.

- Identification of Core Theoretical Lenses: General systems theory was selected as the overarching framework due to its emphasis on interconnectedness, feedback, and holistic analysis, which are crucial for understanding complex socio-organizational phenomena like immigrant integration.

- 2.

- Targeted Literature Search: A broad search of academic databases (e.g., Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar) was conducted using keywords such as ‘immigrant integration,’ ‘workforce diversity,’ ‘organizational systems,’ ‘human resource management for immigrants,’ ‘systems theory in organizations,’ and ‘agile governance.’ This search spanned the literature in migration studies, organizational behavior, human resource management, and sociology.

- 3.

- Thematic Analysis and Synthesis: The reviewed literature was analyzed to identify recurring themes, best practices, existing gaps, and critical challenges in immigrant workforce management. Principles from systems theory were then applied to structure these insights into an integrated model.

- 4.

- Model Development and Refinement: The six subsystems of the proposed model were delineated based on logical processes within organizational talent management, adapted specifically for the immigrant context. The relationships and feedback loops between these subsystems were then conceptualized to ensure coherence and dynamism, drawing inspiration from systems thinking. The primary contribution of this methodological approach is the development of a novel, theoretically grounded conceptual framework. It synthesizes disparate streams of literature into a cohesive model that offers new perspectives on managing immigrant talent and fosters a more agile and sustainable approach to organizational governance in this domain. The model itself, and its constituent parts, provide a clear agenda for future empirical validation and refinement.

4. Conceptual Model: A Systems Approach to Immigrant Integration

4.1. Needs Assessment

4.2. Selection

4.3. Training

4.4. Start of the Work

4.5. Development

4.6. End of the Work

5. Theoretical and Practical Implications of the Systems Model and Future Directions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Contribution to Social Resilience

5.4. Challenges and Limitations in Implementation

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gherheș, V.; Dragomir, G.-M.; Cernicova-Buca, M. Migration intentions of Romanian engineering students. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, L. Connections between U.S. Female Migration and Family Formation and Dissolution. Migr. Int. 2004, 3, 60–82. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Migration. Available online: https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/msite/wmr-2024-interactive (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Su, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, L. The Effect of the Use of Digital Technology on the Impact of Labor Outflow on Rural Collective Action: A Social–Ecological Systems Perspective. Systems 2025, 13, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhang, X. How Does Rural Resilience Affect Return Migration: Evidence from Frontier Regions in China. Systems 2025, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oaxaca Carrasco, A.L.; Aguila, E.; Reyes, A.; Salinas Navarro, S. Emigration and Cognitive Aging Among Mexican Return Migrants. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2025, 47, 07399863251316610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumat, L.; Castillo Jara, S. EU-Latin America Relations: Analyzing the Dynamics of Bi-regional Migration Governance. In The Palgrave Handbook of EU-Latin American Relations; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 535–553. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, M.; Flores, I.; Morgan, M. More unequal or not as rich? Revisiting the Latin American exception. World Dev. 2024, 184, 106737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, M.; Nambu, S. Linguistic Landscape of Immigrants in Japan: A Case Study of Japanese Brazilian Communities. J. Multicult. Multiling. Dev. 2024, 45, 1616–1632. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicka, M. Middle class by effort? Immigration, nation, and class from a transnational and intersectional perspective. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2024, 50, 1758–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marroni, M.; Meneses, G. El fin del sueño americano. Mujeres migrantes muertas en la frontera México-Estados Unidos. Migr. Int. 2006, 3, 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Foreign-Born Workers: Labor Force Characteristics—2024; USDL-25-0847; U.S. Department of Labor: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: www.bls.gov/cps (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Livi Bacci, M. Does Europe need mass immigration? J. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 18, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middermann, L.H. Do immigrant entrepreneurs have natural cognitive advantages for international entrepreneurial activity? Sustainability 2020, 12, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, S.; Wheeler, M.; Gallant, B.; Schocat, C.; Maharjan, E.; Mangeli, B. “How much of myself do I have to erase to be Canadian?” South Asians and Arabs in the workplace. Consult. Psychol. J. 2025, 77, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Hermansen, A.S. Wage disparities across immigrant generations: Education, segregation, or unequal pay? ILR Rev. 2024, 77, 598–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farashah, A.; Blomquist, T.; Bešić, A. The impact of workplace diversity climate on the career satisfaction of skilled migrant employees. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2025, 22, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A. Flexibilización y organización del trabajo. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2005, 11, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, H. La gerencia del cambio en contexto de globalización. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2004, 10, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, E.; Camacho, K. The darkside of the Colombian floriculture sector’s corporate social responsability practices. Innovar 2006, 16, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications; George Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Wacker, J.G. A Definition of Theory: Research Guidelines for Different Theory-Building Research Methods in Operations Management. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 16, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.C.; Geroy, G.D.; Baker, N. Managing expatriates: A systems approach. Manag. Decis. 1996, 34, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dass, P.; Parker, B. Strategies for managing human resource diversity: From resistance to learning. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1999, 13, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, G.C.; Bell, M.P.; Virick, M. Strategic human resource management: Employee involvement, diversity, and international issues. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1998, 6, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. Beyond Race and Gender; American Management Association: New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 9780613916318. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, N. International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior; PWS-Kent Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1991; ISBN 9780534062583. [Google Scholar]

- García-Morato, M. Gestión de la Diversidad Cultural en las Empresas; Fundación Bertelsmann: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan, T.P. Traits, attitudes, and skills that are related to intercultural effectiveness and their implications for cross-cultural training: A review of the literature. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1990, 14, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tye, M.; Chen, P. Selection of Expatriates: Decision-Making Models Used by HR Professionals. Hum. Resour. Plan. 2005, 28, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.M.; McMahan, G.C. Theoretical perspectives for strategic human resource management. J. Manag. 1992, 18, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlander, G.; Snell, S. Administracion de Recursos Humanos, 12th ed.; Cengage Learning Editores S.A. de C.V: Mexico City, Mexico, 2001; ISBN 9706861084. [Google Scholar]

- Kushnirovich, N. Wage gap paradox: The case of immigrants from the FSU in Israel. Int. Migr. 2018, 56, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrazco, C.; Maldonado-Radillo, S.; López, V. Evaluación de la validez y confiabilidad de un instrumento de medición de la gestión de la diversidad: Industria aeroespacial. Rev. Int. Adm. Finanz. 2014, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jaén, M.; Cebas, L.; Mompó, I.; Pereda, A. Gestión de la diversidad cultural en las organizaciones: Una propuesta práctica. EduPsykhé 2011, 10, 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons, S.R.; Baggs, J.; Brannen, M.Y. Intersectional arithmetic: How gender, race and mother tongue combine to impact immigrants’ work outcomes. J. World Bus. 2020, 55, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, F.; Cuadrado, I.; Navas, M. Las nuevas expresiones del pre-juicio racial: Aspectos teóricos y empíricos. In Estudios de Psicología Social; Morales, J., Huici, C., Eds.; UNED: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulla, K. Human capital accumulation: Evidence from immigrants in low-income countries. J. Comp. Econ. 2020, 48, 951–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, A.; Tamborini, C.R. Immigrants’ economic assimilation: Evidence from longitudinal earnings records. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2018, 83, 686–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.; Rodríguez, A. Variables predictoras de la actitud hacia los inmigrantes en la Región de Murcia (España). An. psicol. 2006, 22, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, C.; Igartua, J.; Otero, J. Imágenes de la inmigración a través de la fotografía de prensa. Un Análisis De Contenido. Comun. Y Soc. 2006, 19, 103–128. [Google Scholar]

- Roett, R. Estados Unidos y América Latina: Estado actual de las relaciones. Nueva Soc. 2006, 206, 110–125. [Google Scholar]

- OIM (Ed.) Impactos de la Crisis Sobre la Población Inmigrante; Organización Internacional de las Migraciones: Grand-Saconnex, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- González, F. Etnodiscriminación hacia el afrovenezolano en la educación secundaria. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2005, 11, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjas, G.J. Native internal migration and the labor market impact of immigration. J. Hum. Resour. 2006, 41, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, J.G. Immigrant skill utilization in the Canadian labour market: Implications of human capital research. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2001, 2, 347–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, L. Relaciones laborales especiales: Las empresas de trabajo temporal y las cooperativas. ¿Qué pueden hacer los sindicatos? Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2005, 11, 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, E. El proceso de incorporación de inmigrantes mexicanos a la vida y el trabajo en Los Ángeles. Migr. Int. 2005, 3, 136–198. [Google Scholar]

- Farías, P. Identifying the factors that influence eWOM in SNSs: The case of Chile. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 852–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitah, M.; Toth, D.; Smutka, L.; Maitah, K.; Jarolínová, V. Income differentiation as a factor of unsustainability in forestry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, M. Migration policy and immigrants’ labor market performance. Int. Migr. Rev. 2020, 54, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, M.; Oddou, G. The dimensions of expatriate acculturation: A review. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W. The Factors Influencing Expatriates. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2005, 2, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, P.; Manzur, E.; Olavarrieta, S.; Farías, P. La cultura nacional y su impacto en los negocios: El caso chileno. Estud. Gerenc. 2007, 23, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzur, E.; Uribe, R.; Hidalgo, P.; Olavarrieta, S.; Farías, P. Comparative advertising effectiveness in Latin America: Evidence from Chile. Int. Mark. Rev. 2012, 29, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddou, G. Managing your expatriates: What the successful firms do. Hum. Resour. Plan 1991, 14, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Kranenburg, R. Work Goals of Migrant Workers. Hum. Relat. 1974, 27, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antecol, H.; Cobb-Clark, D.A.; Trejo, S.J. Immigration policy and the skills of immigrants to Australia, Canada, and the United States. J. Hum. Resour. 2003, 38, 192–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.D.; Davis, M.R.; Rodríguez, J.; Bates, S.C. Observed parenting practices of first-generation Latino families. J. Community Psychol. 2006, 34, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo, L.; Zubrinsky, C.L. Attitudes on residential integration: Perceived status differences, mere in-group preference, or racial prejudice? Soc. Forces 1996, 74, 883–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanrıkulu, F. The political economy of migration and integration: Effects of immigrants on the economy in turkey. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2020, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, A.K. How ‘skill’ definition affects the diversity of skilled immigration policies. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020, 46, 2533–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.F.; Bochner, S. Culture Shock: Psychological Reactions to Unfamiliar Environments; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1986; ISBN 9780416366709. [Google Scholar]

- Black, J.S. Work role transitions: A study of American expatriate managers in japan. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1988, 19, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binford, L. Campos agrícolas, campos de poder: El Estado mexicano, los granjeros canadienses y los trabajadores temporales mexicanos. Migr. Int. 2006, 3, 54–80. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, V. Immigration Policy and Human Resource Development. HR Spectr. 1999, 1–4. Available online: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/8f28d739-73a4-4448-8676-f0c77a2768d8/content (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Farías, P. Medición y representación gráfica de las distancias culturales entre países latinoamericanos. Converg. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2016, 23, 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McEntee, H. Comunicación Intercultural. Bases Para la Comunicación Efectiva en el Mundo Actual; McGraw-Hill: Mexico City, Mexico, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, S. Los cargos communitarios y la transpertenencia de los migrantes mixes de Oaxaca en Estados Unidos. Migr. Int. 2006, 3, 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Agyekum, B.; Siakwah, P.; Boateng, J.K. Immigration, education, sense of community and mental well-being: The case of visible minority immigrants in Canada. J. Urban. 2020, 14, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, A.T. Sojourner adjustment. Psychol. Bull. 1982, 91, 540–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoko, O.B.; Härtel, C.E.J. Cultural differences at work: How managers deepen or lessen the cross-racial divide in their workgroups. Qld. Rev. 2000, 7, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Quintero, J.D. La emigración latinoamericana: Contexto global y asentamiento en España. Acciones Investig. Soc. 2005, 21, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zamudio, P. Lazos cambiantes: Comunidad y adherencias sociales de migrantes mexicanos en Chicago. Migr. Int. 2003, 2, 84–106. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, M. Latinos: Cada día más Pobres en EE.UU. BBC Mundo 2004. Available online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/spanish/business/barometro_economico/newsid_4067000/4067725.stm (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Hidalgo, P.; Manzur, E.; Olavarrieta, S.; Farías, P. Customer retention and price matching: The AFPs case. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farías, P. Determinants of knowledge of personal loans’ total costs: How price consciousness, financial literacy, purchase recency and frequency work together. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, A.L.; Rosen, E. Hiding within racial hierarchies: How undocumented immigrants make residential decisions in an American city. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 1857–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Yao, C.; Roche, M.; Wang, M. The double-edged sword of acculturation: Navigating work-family conflict among immigrants. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2025, 105, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Buckingham, L. Methodological Considerations for Qualitative Research With Older Migrants: Insights From Ethnic Chinese in New Zealand. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2025, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, F. Migration Strategies in Urban Contexts: Labor Migration from Mexico City to the United States. Migr. Int. 2004, 3, 34–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cachón, L. La inmigración de mañana en la España de la Gran Recesión y después. Panor. Soc. 2013, 16, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farías, P. Leveraging a Systems Approach for Immigrant Integration: Fostering Agile, Resilient, and Sustainable Organizational Governance. Systems 2025, 13, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060467

Farías P. Leveraging a Systems Approach for Immigrant Integration: Fostering Agile, Resilient, and Sustainable Organizational Governance. Systems. 2025; 13(6):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060467

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarías, Pablo. 2025. "Leveraging a Systems Approach for Immigrant Integration: Fostering Agile, Resilient, and Sustainable Organizational Governance" Systems 13, no. 6: 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060467

APA StyleFarías, P. (2025). Leveraging a Systems Approach for Immigrant Integration: Fostering Agile, Resilient, and Sustainable Organizational Governance. Systems, 13(6), 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060467