Attributes Influencing Visitors’ Experiences in Conservation Centers with Different Social Identities: A Topic Modeling Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Attributes of Visitors’ Experiences with Conservation in Conservation Centers

2.2. Effects of Social Identities on Attitudes Toward Characteristic Flagship Species via the Out-Group Homogeneity Effect

2.3. Topic Modeling with Online Reviews

3. Methodology

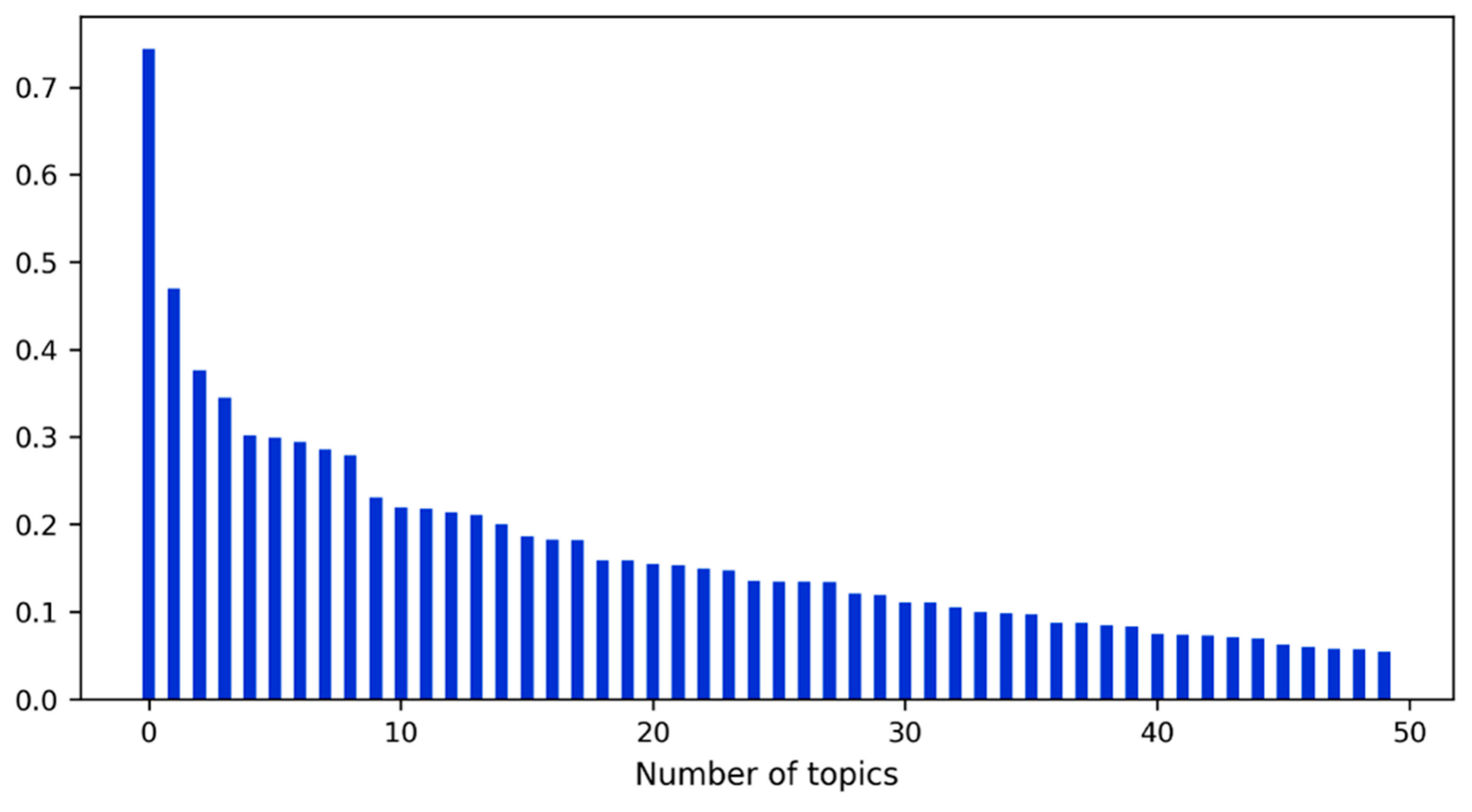

3.1. Anchored CorEx Modeling Approach

3.2. Data Collection and Data Preprocessing

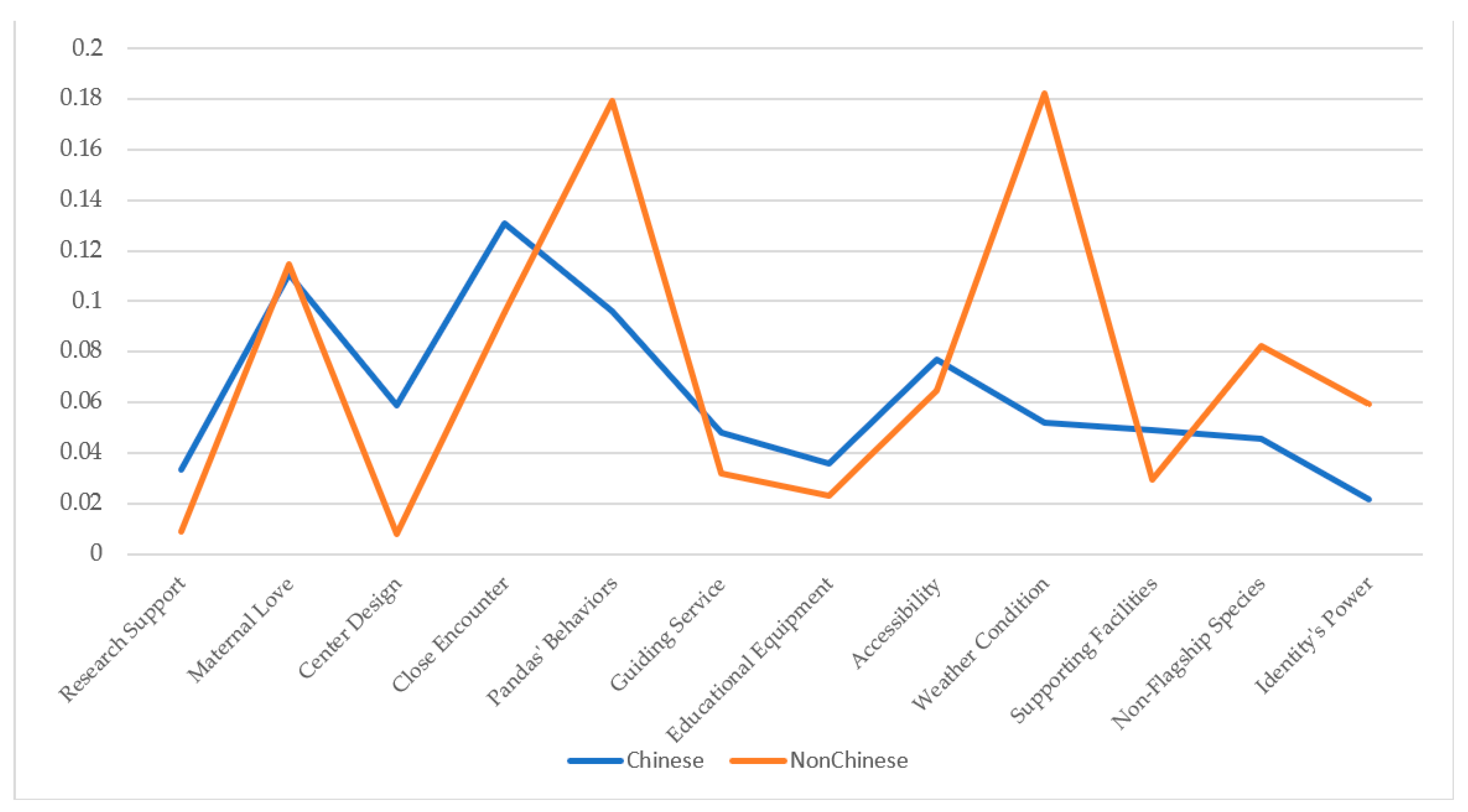

4. Findings

5. Discussion

6. Implications and Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moriuchi, E.; Murdy, S. Increasing Donation Intentions toward Endangered Species: An Empirical Study on the Mediating Role of Psychological and Technological Elements of VR. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1302–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. Review of Panda Nation: The Construction and Conservation of China’s Modern Icon. China Rev. Int. 2019, 26, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Lin, C.A. Are Pandas Effective Ambassadors for Promoting Wildlife Conservation and International Diplomacy? Sustainability 2022, 14, 11383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreedhar, G.; Mourato, S. Experimental Evidence on the Impact of Biodiversity Conservation Videos on Charitable Donations. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 158, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilbert, J.; Scheersoi, A. Learning Outcomes Measured in Zoo and Aquarium Conservation Education. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 37, e13891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.B.; Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J. Penguin Promises: Encouraging Aquarium Visitors to Take Conservation Action. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 859–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellish, S.; Pearson, E.L.; McLeod, E.M.; Tuckey, M.R.; Ryan, J.C. What Goes up Must Come down: An Evaluation of a Zoo Conservation-Education Program for Balloon Litter on Visitor Understanding, Attitudes, and Behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1393–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellish, S.; Ryan, J.C.; Pearson, E.L.; Tuckey, M.R. Research Methods and Reporting Practices in Zoo and Aquarium Conservation-Education Evaluation. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 33, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. Learning from Museums; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4422-7600-0. [Google Scholar]

- Packer, J. Learning for Fun: The Unique Contribution of Educational Leisure Experiences. Curator Mus. J. 2006, 49, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, W. Zoos and Tourism: Conservation, Education, Entertainment? Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1-84541-163-3. [Google Scholar]

- Folusade, C.A.; Tunde-Ajayi, O.A.; Ojo, B.D. Examining Motivation and Perception of Visitors at Lekki Conservation Centre (LCC) in Nigeria. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2020, 16, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidakun, E.T.; Tunde-Ajayi, O.A. Tourists’ Choice for Tour Guides in Enhancing Site Experience at Lekki Conservation Centre, Lagos State. Int. J. Prog. Sci. Technol. 2021, 30, 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Nwokorie, E.C.; Adeniyi, E.E. Tourists’ Perception of Ecotourism Development in Lagos Nigeria: The Case of Lekki Conservation Centre. Turizam 2020, 25, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidyarko, A.I.F.; Gayatri, A.C.; Rifa, V.A.; Astuti, A.; Kusumaningrum, L.; Mau, Y.S.; Rudiharto, H.; Setyawan, A.D. Reviews: Komodo National Park as a Conservation Area for the Komodo Species (Varanus komodoensis) and Sustainable Tourism (Ecotourism). Int. J. Trop. Drylands 2021, 5, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruder, J.; Burakowski, L.M.; Park, T.; Al-Haddad, R.; Al-Hemaidi, S.; Al-Korbi, A.; Al-Naimi, A. Cross-Cultural Awareness and Attitudes Toward Threatened Animal Species. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 898503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Tajfel, H. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. Psychol. Intergroup Relat. 1986, 5, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Chien, P.M.; Ritchie, B.W.; Pappu, R. When Compatriot Tourists Behave Badly: The Impact of Misbehavior Appraisal and Outgroup Criticism Construal. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 23, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Li, Y.; Fu, X.; Yu, X.; Lv, X. When Guests Become Hosts: The Boomerang Effect of Tourists’ Negative Behaviors on Their Country of Origin. J. Travel Res. 2024, 0, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsong, M.H.; Metcalf, A.L.; Metcalf, E.C.; Nesbitt, H.K.; Gude, J.A. The Influence of Social Identity on Attitudes toward Wildlife. Conserv. Biol. 2024, 38, e14243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-M. Unexpected Threat from Conservation to Endangered Species: Reflections from the Front-Line Staff on Sea Turtle Conservation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 2255–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eeden, L.M.; Newsome, T.M.; Crowther, M.S.; Dickman, C.R.; Bruskotter, J. Social Identity Shapes Support for Management of Wildlife and Pests. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 231, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, C.E.; Bastian, B. Solidarity with Animals: Assessing a Relevant Dimension of Social Identification with Animals. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arowosafe, F.; Oni, F.; Tunde-Ajayi, O. Effectiveness of Interpretative Signs on Visitors’ Behaviour and Satisfaction at Lekki Conservation Center, Lagos State, Nigeria. Czech J. Tour. 2023, 12, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. Exaggeration in Fake vs. Authentic Online Reviews for Luxury and Budget Hotels. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 62, 102416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazlan, N.H.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Chang, W. Navigating the Online Reputation Maze: Impact of Review Availability and Heuristic Cues on Restaurant Influencer Marketing Effectiveness. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2024, 33, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Vu, H.Q.; Li, G.; Law, R. Topic Modelling for Theme Park Online Reviews: Analysis of Disneyland. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Luo, J.M.; Chi, C.G.-Q.; Gursoy, D. Examination of Experience Attributes of Parks in Urban Tourist Destinations and Their Influence on Visitors’ satisfaction: A Topic Modelling Approach. Leis. Stud. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Luo, J.M. Topic Modelling for Wildlife Tourism Online Reviews: Analysis of Quality Factors. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 2317–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmin-Pui, L.S.; Perkins, R. How Do Visitors Relate to Biodiversity Conservation? An Analysis of London Zoo’s ‘BUGS’ Exhibit. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 1462–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabb, G.B. The Evolution of Zoos from Menageries to Centers of Conservation and Caring. Curator Mus. J. 2004, 47, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R.; Escribano, N.; Casas, M.; Pino-del-Carpio, A.; Villarroya, A. The Role of Zoos and Aquariums in a Changing World. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2023, 11, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, S.L.; Jensen, E.A.; Tracey, L.; Marshall, A.R. Evaluating the Impacts of Theatre-Based Wildlife and Conservation Education at the Zoo. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 1231–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R. Motivational Factors and the Visitor Experience: A Comparison of Three Sites. Curator Mus. J. 2002, 45, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Hughes, K.; Dierking, L. Conservation Learning in Wildlife Tourism Settings: Lessons from Research in Zoos and Aquariums. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, N.; Cohen, S. The Public Face of Zoos: Images of Entertainment, Education and Conservation. Anthrozoös 2011, 24, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-S. Measurement of Visitors’ Satisfaction with Public Zoos in Korea Using Importance-Performance Analysis. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaffashi, S.; Yacob, M.R.; Clark, M.S.; Radam, A.; Mamat, M.F. Exploring Visitors’ Willingness to Pay to Generate Revenues for Managing the National Elephant Conservation Center in Malaysia. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 56, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.; Kelling, A.; Poline, L.; Bloomsmith, M.; Maple, T. Post-Occupancy Evaluation of Zoo Atlanta’s Giant Panda Conservation Center: Staff and Visitor Reactions. Zoo Biol. 2003, 22, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.C.; Mendes, J.; do Valle, P.O.; Scott, N. Co-Creating Animal-Based Tourist Experiences: Attention, Involvement and Memorability. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L.; Gunther, K.; Rosen, T.; Schwartz, C. Visitor Perceptions of Roadside Bear Viewing and Management in Yellowstone National Park. George Wright Forum 2015, 32, 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Bexell, S.M.; Jarrett, O.S.; Lan, L.; Yan, H.; Sandhaus, E.A.; Zhihe, Z.; Maple, T.L. Observing Panda Play: Implications for Zoo Programming and Conservation Efforts. Curator Mus. J. 2007, 50, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Huawen, J.S.; Haobin, B.Y. Embracing Panda—Assessing the Leisure Pursuits of Subscribers to China’s iPanda Live Streaming Platform. Leis. Stud. 2022, 41, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Wu, B.; Morrison, A.M.; Shu, H.; Wang, M. Analysis of Wildlife Tourism Experiences with Endangered Species: An Exploratory Study of Encounters with Giant Pandas in Chengdu, China. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.A.; Hashim, Z.; Aziz, N.; Khalid, M. Visitors’ Experinces and Resource Protection (VERP) at National Elephant Conservation Centre, Kuala Gandah. In Proceedings of the Seminar on Gunung Benom Scientific Expedition, Putrajaya, Malaysia, 15–16 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, K. Measuring the Impact of Viewing Wildlife: Do Positive Intentions Equate to Long-Term Changes in Conservation Behaviour? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniasari, K. Understanding Visitors’ Experiences in Nature-Based Tourism: A Case Study of Komodo National Park Indonesia. Master’s Thesis, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.X.; Pearce, P.; Chen, G. Not Losing Our Collective Face: Social Identity and Chinese Tourists’ Reflections on Uncivilised Behaviour. Tour. Manag. 2019, 73, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social Categorization, Social Identity and Social Comparison; Academic Press: London, UK, 1978; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. Organ. Identity Read. 1979, 56, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A.; Turner, J.C. Social Identity and Conformity: A Theory of Referent Informational Influence. Curr. Issues Eur. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 2, 139–182. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, C.M.; Ryan, C.S.; Park, B. Accuracy in the Judgment of In-Group and out-Group Variability. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Social Identity and Self-Categorization. In The SAGE Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Osebor, I.M. Inclusive Symbolic Frames and Codes Shaping Cultural Identity and Values. MEΘEXIS J. Res. Values Spiritual. 2024, 4, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, C. Ethos, World-View and the Analysis of Sacred Symbols. Antioch Rev. 1957, 17, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, P.J. The Salience of Social Categories. In Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1987; pp. 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M.B.; Gardner, W. Who Is This “We”? Levels of Collective Identity and Self Representations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, T.M.; Sedikides, C. Out-Group Homogeneity Effects in Natural and Minimal Groups. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 536–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiassen, A.; Kock, F.; Nørfelt, A. Tourism Affinity and Its Effects on Tourist and Resident Behavior. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, C.W.; van Zomeren, M.; Zebel, S.; Vliek, M.L.W.; Pennekamp, S.F.; Doosje, B.; Ouwerkerk, J.W.; Spears, R. Group-Level Self-Definition and Self-Investment: A Hierarchical (Multicomponent) Model of in-Group Identification. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, C.E.; Sukhanova, K.; Bastian, B. Social Identification with Animals: Unpacking Our Psychological Connection with Other Animals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 118, 991–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.W. Intergroup Attitudes as a Function of Different Dimensions of Group Identification and Perceived Intergroup Conflict. Self Identity 2002, 1, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Turner, J.C. Intergroup Behaviour, Self-Stereotyping and the Salience of Social Categories. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 26, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H.; Highfill, L.E.; Makecha, R.; Baksic, W.; Graves, S.; Heaton, E. Is There Value in Including Information about Animal Cognition and Emotion in Zoo Messaging? Visit. Stud. 2023, 26, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, C.E.; Gagné, C.; Bastian, B. Exploring the Role of Our Contacts with Pets in Broadening Concerns for Animals, Nature, and Fellow Humans: A Representative Study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen Ben-Arye, R.; Halali, E. Giving Farm Animals a Name and a Face: Eliciting Animal Advocacy among Omnivores Using the Identifiable Victim Effect. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 93, 102193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Barnes, S.J.; Jia, Q. Mining Meaning from Online Ratings and Reviews: Tourist Satisfaction Analysis Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, K.; Kitayama, S. Outgroup Homogeneity Effect in Perception: An Exploration with Ebbinghaus Illusion. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 14, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, R.J.; Reing, K.; Kale, D.; Ver Steeg, G. Anchored Correlation Explanation: Topic Modeling with Minimal Domain Knowledge. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2017, 5, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Shang, Z. Hiking Experience Attributes and Seasonality: An Analysis of Topic Modelling. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 2984–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefieva, V.; Egger, R.; Yu, J. A Machine Learning Approach to Cluster Destination Image on Instagram. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, R.F.; Wang, Y.; Nguyen, T.; Vasilakes, J.; Bian, J.; He, Z.; Zhang, R. Analyzing Social Media Data to Understand Consumer Information Needs on Dietary Supplements. In MEDINFO 2019: Health and Wellbeing e-Networks for All; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 323–327. [Google Scholar]

- Ounacer, S.; Mhamdi, D.; Ardchir, S.; Daif, A.; Azzouazi, M. Customer Sentiment Analysis in Hotel Reviews Through Natural Language Processing Techniques. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, R.; Yu, J. Identifying Hidden Semantic Structures in Instagram Data: A Topic Modelling Comparison. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Peng, P.; Lu, F.; Claramunt, C.; Qiu, P.; Xu, Y. Mining Tourist Preferences and Decision Support via Tourism-Oriented Knowledge Graph. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Hu, Z.; Law, R. Exploring Online Consumer Experiences and Experiential Emotions Offered by Travel Websites That Accept Cryptocurrency Payments. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 119, 103721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, N. A Generalized Kruskal-Wallis Test for Comparing K Samples Subject to Unequal Patterns of Censorship. Biometrika 1970, 57, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, L.; Tang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, L. Big Data in Tourism Research: A Literature Review. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Hu, Z.; Leong, A.M.W. Exploring the Experience Attributes of Intangible Cultural Heritage through Big Data Analytics. J. Vacat. Mark. 2025, 0, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Park, S. A Cross-Cultural Anatomy of Destination Image: An Application of Mixed-Methods of UGC and Survey. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Zhang, T.; Gao, B.; Bose, I. What Do Hotel Customers Complain about? Text Analysis Using Structural Topic Model. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnusyan, R.; Almotairi, R.; Almufadhi, S.; Shargabi, A.A.; Alshobaili, J. A Semi-Supervised Approach for User Reviews Topic Modeling and Classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computing and Information Technology (ICCIT-1441), Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, 9–10 September 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Z.; Luo, J.M. Topic Modeling for Hiking Trail Online Reviews: Analysis of the Mutianyu Great Wall. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, H. Digital Panda Nationalism: Constructing Nationalist Discourse through Metaphors in Chinese Social Media. Discourse Context Media 2025, 65, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, A. “PANDAS, LIONS, AND DRAGONS, OH MY!”: How White Adoptive Parents Construct Chineseness. J. Asian Am. Stud. 2009, 12, 285–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leith, M.S. Political Discourse and National Identity in Scotland; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-7486-8862-3. [Google Scholar]

- Small, E. The New Noah’s Ark: Beautiful and Useful Species Only. Part 2. The Chosen Species. Biodiversity 2012, 13, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, J.A.C.; Faber, N.S.; Crockett, M. Preferences and Beliefs in Ingroup Favoritism. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, M.; Cioffi-Revilla, C.; Crooks, A. The Effect of In-Group Favoritism on the Collective Behavior of Individuals’ Opinions. Adv. Complex Syst. 2015, 18, 1550002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, D.; and Jang, S. (Shawn) Travel-Based Learning: Unleashing the Power of Destination Curiosity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 396–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khu, J.M.T. Cultural Curiosity: Thirteen Stories About the Search for Chinese Roots; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-520-92491-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.X.; Fong, L.; McCabe, S. Intergroup Identity Conflict in Tourism: The Voice of the Tourist. J. Travel Res. 2025, 64, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, G.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Morrison, A.M. Red Tourism in China: Emotional Experiences, National Identity and Behavioural Intentions. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 1037–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, R.C.; Stellar, J.E. When the Ones We Love Misbehave: Exploring Moral Processes within Intimate Bonds. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 122, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Home, R.; Keller, C.; Nagel, P.; Bauer, N.; Hunziker, M. Selection Criteria for Flagship Species by Conservation Organizations. Environ. Conserv. 2009, 36, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.H. Interpretation: Making a Difference on Purpose; Fulcrum: Golden, CO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weiler, B.; Ham, S.H. Tour Guides and Interpretation. In The Encyclopedia of Ecotourism; CABI Books: London, UK, 2001; pp. 549–563. ISBN 978-0-85199-368-3. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Liu, X.; Zheng, L.; Cai, Y. Don’t Squeeze Me! Exploring the Mechanisms and Boundary Conditions between Social Crowding and Uncivilised Tourist Behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 28, 2021–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attributes | TOP 10 Words | From |

|---|---|---|

| Research Support | donation, hold, pay, minute, rmb, cash, camera, money, picture, certificate | (Hehir et al., 2023); (Piao & Managi, 2022) |

| Maternal Love | baby, cub, nursery, adult, incubator, mother, lucky, crib, tiny, breed | [39,46] |

| Center Design | enclosure, habitat, natural, zoo, separate, lay, hole, ground, captivity, spacious | [5] |

| Close Encounter | close, watch, photo, encounter, personal, fun, contact, shot, fence, ops | [41] |

| Pandas’ Behaviors | eat, play, sleep, drink, bamboo, tree, climb, walk, afternoon, lie | [42,43] |

| Guided Services | guide, staff, conservation, explain, question, tour, answer, english, speak, skill | [13,14,15]; |

| Educational Equipment | learn, video, signage, knowledge, museum, short, documentary, life, history, purpose | (Arowosafe et al., 2023) |

| Accessibility | easy, entrance, transport, taxi, bus, ticket, hotel, shuttle, accessible, metro | [14,15] |

| Weather Conditions | weather, hot, air, summer, moon, condition, inside, sun, glass, car | [47] |

| Self-Feeling | experience, lifetime, amaze, wonderful, unforgettable, unique, amazing, pre, opposite, background | (Arowosafe et al., 2020) |

| Uncivilized Behaviors | noise, cut, shout, people, sign, chinese, animal, guard, move, security | (Rahman et al., 2010) |

| Supporting Facilities | restaurant, shop, hospital, souvenir, food, kitchen, gift, lunch, toilet, café | [14] |

| Non-Flagship Species | swan, peacock, lake, black, koi, fish, carp, road, white, bird | New |

| Identity’s Power | china, national, treasure, precious, highlight, holiday, nation, travel, live, iconic | New |

| Keepers’ Behaviors | feed, breed, keeper, interact, program, cage, volunteer, pole, cleaning, job | [44] |

| Non-Chinese Visitors | Chinese Visitors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std.Error | t | p | β | B | Std.Error | t | p | β | |

| (constant) | 4.509 ** | 0.053 | 84.462 | 0 | - | 3.867 ** | 0.233 | 16.617 | 0 | - |

| Research Support | 0.311 ** | 0.103 | 3.014 | 0.003 | 0.047 | 1.756 ** | 0.449 | 3.916 | 0 | 0.131 |

| Maternal Love | 0.225 ** | 0.067 | 3.363 | 0.001 | 0.072 | 0.857 ** | 0.244 | 3.513 | 0 | 0.301 |

| Center Design | −0.004 | 0.081 | −0.054 | 0.957 | −0.001 | 0.577 | 0.404 | 1.429 | 0.153 | 0.048 |

| Close Encounter | 0.280 ** | 0.067 | 4.181 | 0 | 0.088 | 0.594 * | 0.25 | 2.375 | 0.018 | 0.177 |

| Pandas’ Behaviors | 0.175 * | 0.071 | 2.461 | 0.014 | 0.05 | 0.834 ** | 0.241 | 3.464 | 0.001 | 0.344 |

| Guided Services | 0.342 ** | 0.085 | 4.005 | 0 | 0.068 | 0.411 | 0.287 | 1.432 | 0.152 | 0.071 |

| Educational Equipment | 0.066 | 0.095 | 0.689 | 0.491 | 0.011 | 0.417 | 0.302 | 1.382 | 0.167 | 0.058 |

| Accessibility | 0.164 * | 0.075 | 2.185 | 0.029 | 0.044 | 0.585 * | 0.262 | 2.235 | 0.026 | 0.144 |

| Weather Conditions | −0.201 * | 0.081 | −2.469 | 0.014 | −0.044 | 0.644 ** | 0.244 | 2.643 | 0.008 | 0.254 |

| Self-Feeling | 0.272 ** | 0.077 | 3.539 | 0 | 0.065 | 0.521 | 0.327 | 1.595 | 0.111 | 0.062 |

| Uncivilized Behaviors | −0.690 ** | 0.109 | −6.314 | 0 | −0.099 | −0.324 | 0.332 | −0.977 | 0.329 | −0.038 |

| Supporting facilities | 0.190 * | 0.093 | 2.04 | 0.041 | 0.034 | 1.112 ** | 0.301 | 3.692 | 0 | 0.165 |

| Non-Flagship Species | 0.298 ** | 0.084 | 3.545 | 0 | 0.061 | 0.860 ** | 0.247 | 3.481 | 0.001 | 0.268 |

| Identity’s Power | 0.265 * | 0.124 | 2.138 | 0.033 | 0.032 | 0.654 * | 0.256 | 2.554 | 0.011 | 0.161 |

| Keepers’ Behaviors | 0.071 | 0.078 | 0.913 | 0.361 | 0.016 | 0.842 ** | 0.26 | 3.238 | 0.001 | 0.198 |

| Attributes | b0 − b1 | Freq | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (constant) | −0.642 | 1000 | 0 |

| Research Support | 1.445 | 0 | 0 |

| Maternal Love | 0.631 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Center Design | 0.581 | 6 | 0.006 |

| Close Encounter | 0.314 | 47 | 0.047 |

| Pandas’ Behaviors | 0.659 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Guided Services | 0.069 | 371 | 0.371 |

| Educational Equipment | 0.352 | 86 | 0.086 |

| Accessibility | 0.421 | 18 | 0.018 |

| Weather Conditions | 0.845 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-Feeling | 0.249 | 115 | 0.115 |

| Uncivilized Behaviors | 0.366 | 176 | 0.176 |

| Supporting facilities | 0.921 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-Flagship Species | 0.561 | 4 | 0.004 |

| Identity’s Power | 0.389 | 58 | 0.058 |

| Keepers’ Behaviors | 0.771 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Attributes | p-Value | Sig < 0.05 | H-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Support | 0.000 | Yes | 103.989 |

| Maternal Love | 0.001 | Yes | 10.085 |

| Center Design | 0.000 | Yes | 259.753 |

| Close Encounter | 0.000 | Yes | 42.579 |

| Pandas’ Behaviors | 0.000 | Yes | 64.870 |

| Guiding Service | 0.001 | Yes | 25.165 |

| Educational Equipment | 0.001 | Yes | 23.314 |

| Accessibility | 0.003 | Yes | 8.861 |

| Weather Conditions | 0.000 | Yes | 563.263 |

| Self-Feeling | 0.066 | No | 3.391 |

| Uncivilized Behaviors | 0.546 | No | 0.365 |

| Supporting Facilities | 0.000 | Yes | 42.400 |

| Non-Flagship Species | 0.000 | Yes | 30.457 |

| Identity’s Power | 0.000 | Yes | 143.059 |

| Keepers’ Behaviors | 0.634 | No | 0.227 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Chen, P.; Luo, J.M. Attributes Influencing Visitors’ Experiences in Conservation Centers with Different Social Identities: A Topic Modeling Approach. Systems 2025, 13, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060442

Li Z, Chen P, Luo JM. Attributes Influencing Visitors’ Experiences in Conservation Centers with Different Social Identities: A Topic Modeling Approach. Systems. 2025; 13(6):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060442

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhongkai, Ping Chen, and Jian Ming Luo. 2025. "Attributes Influencing Visitors’ Experiences in Conservation Centers with Different Social Identities: A Topic Modeling Approach" Systems 13, no. 6: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060442

APA StyleLi, Z., Chen, P., & Luo, J. M. (2025). Attributes Influencing Visitors’ Experiences in Conservation Centers with Different Social Identities: A Topic Modeling Approach. Systems, 13(6), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060442