1. Introduction

Since the mid-1990s, the business model (BM) concept has attracted considerable interest from researchers, academics, and market practitioners [

1]. The BM reflects the value companies provide, how they create this value, and how they can profit from the created value [

2,

3]. Helping companies develop and seize value via effective business opportunities, BMs significantly facilitate the development of competitive advantages that enable companies to stay ahead of the competition in the digital era [

4]. Since the mid-1190s, markets, and industries have undergone significant changes (such as globalization, the emergence of the Internet, and the increasing dynamism of markets) [

5,

6]. With the competitive environment constantly changing and other companies quickly imitating successful companies, BMs run the risk of becoming ineffective and obsolete [

7]. A remedy to the stagnation of BMs is BM innovation, which considers the innate dynamics of the business environment [

8] and reduces failure rates [

4]. BMI allows companies to cope with market changes and sustain their financial performance in the digital era [

9]. As a result, in considering the advantages of BMI for different companies, researchers and academics have paid this topic special attention in recent decades [

8].

In contemporary business, BMs need to be grounded in social and environmental concerns. Consequently, CSR has garnered interest from numerous researchers investigating this concept and its effects [

10]. CSR refers to a range of activities that yield numerous benefits for society [

11] and stakeholders [

12].

Since CSR is becoming a central aspect of the value proportions offered to customers, we expect that a strong association will be found between CSR and BMI. While some pioneering research has investigated the relationship between these two concepts [

13,

14], there are still notable gaps in the existing literature. Specifically, the research has not generated conclusive insights into whether the impact of CSR on BMI is direct and significant. Consequently, companies cannot be sure whether they should include CSR in their BMs [

4]. Additionally, the limited research on the connection between BMI and CSR has primarily focused on social enterprises [

15]. There is a difference between social BMs and commercial BMs. In commercial BMs, firms focus on making profits, while in social business models, the company prioritizes addressing environmental and social challenges [

16]. The existing literature has examined social BMIs, while the focus of a large number of companies (almost all) is commercial BMs, as their goal is to make a profit [

17]. Although, in recent years and decades, companies’ attention to the issue of CSR has increased significantly, upon careful examination, it is clear that many companies only increased their rhetoric about CSR in the digital era. In practice, the extent of their involvement in CSR activities is questionable. This difference between the words and actions of companies shows that although many business companies talk about CSR, they have not yet fully integrated CSR into their BMs [

18]. As a result, whether companies are interested in including CSR in their BMs is not yet fully revealed.

The focus of studies that investigating BMI has usually been on big companies, and little research has been conducted on SMEs [

8]. SMEs have emerged as crucial drivers of economic growth and development worldwide. These businesses are estimated to be responsible for generating about 36,300 billion USD annually, which accounts for a major share of the global economic output. In fact, about 400 million SMEs are estimated to be functioning worldwide, making them a vital component of the global economy [

19]. Therefore, their contribution to job creation, innovation, and productivity cannot be overstated, and they significantly influence the economic environment of numerous nations. According to the latest available data, from 2019, a total of 43,650 SMEs are located across more than 800 industrial parks in Iran. Out of these, a significant majority of approximately 78 percent, or 33,800, SMEs were active and functioning. It is noteworthy that out of the total active SMEs, as many as 1100 enterprises were engaged in exporting domestic products to international markets. This reflects the increasing involvement of Iranian SMEs in the global market and their ability to enhance the country’s economic expansion and progress [

20]. According to the Ministry of Industry, Mine, and Trade [

21], SMEs provide a substantial portion of the country’s total employment, which underscores their central role in ensuring economic stability and growth.

This condition is far more critical in Iranian SMEs as the IR-Iran is intertwined with its SMEs and its global position. It is generally acknowledged that the performance and sustainability of SMEs are predominantly a function of internal capabilities but are also related to the wider ecosystem in which the SMEs operate. It is absolutely essential that various stakeholders in this ecosystem (government bodies, financial institutions, suppliers, customers, and educational institutions) understand their role in either fostering or inhibiting the growth of SMEs. The Iranian government has laws and regulations that have a great deal of impact on SMEs. Even when government policies work in their favor, it remains difficult SMEs to become entrenched due to bureaucracy and regulatory inefficiencies. Financial support programs, tax incentives, and entrepreneurship policies are among the key elements influencing this [

22]. However, political instability and economic sanctions limit access to the international markets, foreign investment, and technologies that would be vital for SME development [

23]. Capital access is an important condition influencing SMEs within the state of Iran. Traditional banks require immense collateral, in addition to being risk-averse and lacking financial transparency, which makes it difficult for them to finance agriculture. Most depend on informal sources such as family loans or personal savings—which are usually insufficient for chronic growth [

24]. However, there is a new push to create a better venture capital ecosystem, something that could benefit startups, tech-driven SMEs, and financial technologies (FinTech), which could provide less burdensome sources of financing [

25]. Addressing these barriers and creating a more supportive ecosystem will be critical for unlocking the potential of Iranian SMEs and ensuring their long-term sustainability.

Currently, there is a lack of research concerning SMEs. More research is needed to obtain a better understanding of the challenges, opportunities, and distinct features of SMEs. By conducting more research on SMEs, we can gain more information that can inform policies, strategies, and business practices that are tailored to the specific needs of SMEs. Therefore, it is crucial for academics and researchers to prioritize SMEs in their upcoming studies and publications. In addition, most of the investigations in this area have predominantly taken place in developed countries, while there have been few studies in emerging economies and developing nations [

26].

Furthermore, while numerous studies address CSR and BMI as distinct topics, few have empirically examined the direct influence of CSR on BMI. A significant portion of the existing research depends on conceptual frameworks instead of quantitative or longitudinal data. For example, Schaltegger [

27] investigated the role of sustainability in fostering business model innovation but did not empirically test CSR as a driver. So, this research study investigates the intricate connection between CSR activities, BM, and FP within Iranian SMEs. It investigates how CSR initiatives affect BMI and influence the performance of these organizations. Additionally, this study assessed the prevalence of CSR practices in SMEs and their overall impact on FP. This research aims to clarify the importance of CSR activities in SMEs and the benefits they provide.

To our knowledge, most studies addressing the connection between CSR and BMI consider CSR as a singular, uniform variable. In this study, however, we decompose the variable and investigate the specific effects of the dimensions of CSR on BMI. As a theoretical basis for this endeavor, we rely on the four levels of Carroll’s social responsibility pyramid. This theory allows us to make a theoretical contribution by offering granular insights into how the effects of different CSR dimensions are conditioned by BMI.

Moreover, while a wide consensus exists among scholars regarding the essential economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic aspects of CSR [

28,

29], a notable gap remains concerning corporate environmental responsibility. This study introduces environmental responsibility as a new dimension of CSR, marking a novel addition. Given the growing significance of environmental sustainability in both scholarly discussions and society at large, it was essential to treat the environment as a distinct focus of this research. Therefore, recognizing the environment as an individual dimension, the study seeks to gain a deeper understanding of how these five dimensions of CSR affect BMI’s impact on FP. Consequently, the research question posed is as follows: which dimension of CSR influences BMI, ultimately enhancing firm performance?

The research was conducted in an emerging market: Iran. While CSR compliance and sustainable development may be in their infancy in emerging markets, it is plausible that such matters may be accentuated in these settings. Countries with emerging economies usually face different challenges, such as economic, political, and cultural instability. As a result, this research can provide different results to studies conducted in developed countries. The research was conducted in a Muslim-majority country, which may influence various cultural, social, and ethical aspects of the study. This is significant because they could have an impact on how ethical CSR is perceived and practiced within this context. It is possible that the results of this research may differ from studies that were conducted in other countries, with different cultural and societal conditions.

We utilized subjective data, primarily collected through surveys and interviews, to capture key insights regarding BMI and CSR within the companies involved. While we recognize the importance of objective data, such as financial expenditures on environmental protection and social charity, we argue that subjective data play a crucial role in understanding the strategies, motivations, and internal processes that drive CSR and innovation initiatives. CSR and innovation are complex phenomena that often involve not only measurable financial investments but also cultural and strategic dimensions that are difficult to objectively quantify. For instance, a company’s commitment to sustainability, ethical practices, or social responsibility may not always translate into direct or immediate financial expenditures, but may be reflected in its values, policies, and organizational practices. By capturing the perceptions of key stakeholders—such as managers, employees, and other internal actors—this study highlights the importance of these intangible yet significant factors that influence CSR and innovation.

Moreover, the perceptions of CSR and innovation can serve as early indicators of a company’s commitment to these areas and, in many cases, these subjective measures are closely aligned with real-world outcomes. Many studies in the CSR and innovation literature rely on subjective data to obtain a deeper understanding of corporate behavior, particularly when financial data may be incomplete, unavailable, or inconsistent across firms (e.g., [

30]). While the inclusion of objective financial data would undoubtedly enhance the robustness of the study, the subjective data collected in this study provide a valuable lens through which we can interpret the broader strategic and organizational trends that shape CSR and innovation practices.

There will be a literature review in the following section, where the existing literature and previous studies will be reviewed and hypotheses formulated. Following this, the methodology section explains the research methods, sampling, and data collection procedures. The section on the research results consists of an analysis of the data, as well as an examination of the hypotheses outlined in the study. This is followed by a discussion of the results and conclusions, highlighting the theoretical and managerial implications of this research. As a final point, we state the limitations of this research and make some suggestions for future studies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Business Model Innovation (BMI)

BMI is considered vital for companies to adjust to new circumstances and maintain their performance over time. BMI encompasses how a company generates value and delivers it to customers, relying on various components, including profit, the flow of costs, and revenues [

31]. Although there are multiple conceptualizations of BMI, a single definition of this issue has not yet been provided. Still, it can generally be said that BMI focuses on delivering new value to customers [

32]. From this perspective, BMI, or Business Model Innovation, differs from product and service innovation. It encompasses the innovative activities undertaken by companies that impact various interconnected activities and resources. This form of innovation involves rethinking the entire business model to enhance overall effectiveness and adaptability in the market. BMI encompasses elements such as structures and processes designed to achieve a competitive advantage and enhance performance [

6]. BMI plays a crucial role in helping companies attract new customers by introducing novel approaches to their products and services. This strategy not only enhances customer engagement but also fosters loyalty as businesses adapt to the evolving market demands in the digital era. Additionally, BMI enables companies to develop unique competitive advantages that are challenging for other players in the industry to replicate. By cultivating distinct business models and leveraging innovative practices, organizations can create barriers to imitation, ensuring their market position remains strong and sustainable over time [

4,

32].

Recent research has highlighted the growing influence of digitalization in shaping BMI. As businesses transition toward sustainability and digital transformation, the integration of green and digital strategies into business models becomes essential. Digital technologies, including data analytics, artificial intelligence, and automation, are transforming how companies design, deliver, and capture value, thus enabling more flexible, responsive, and sustainable business models to be established [

33]. In particular, green innovation—encompassing technological and process innovations that reduce environmental impacts—plays a mediating role in translating CSR strategies into improved performance through BMI. In this sense, digitalization is not merely an enabler but a fundamental catalyst for sustainable business model reconfiguration [

34].

2.2. CSR and Its Effect on BMI

CSR is a complex issue that can be examined from different perspectives. Although this concept has a long history in business practices, academic interest in the phenomenon was instigated in the 1950s [

35]. However, despite various reviews of this concept, due to the controversial nature of the concept of CSR [

36], a universally accepted definition of this concept remains absent [

37,

38]. CSR includes the firm’s activities in response to social needs and a firm’s responsibility towards society, which can ultimately lead to the firm obtaining results that benefit society [

17]. Companies in various industries need to engage in CSR activities to satisfy stakeholders’ interests and maintain a sustainable economic unit [

39]. CSR shows how a firm can shoulder the costs and effects its operations have on society and the environment, in addition to its activities in the industry [

40].

CSR has become one of the important concepts in the management literature [

41,

42,

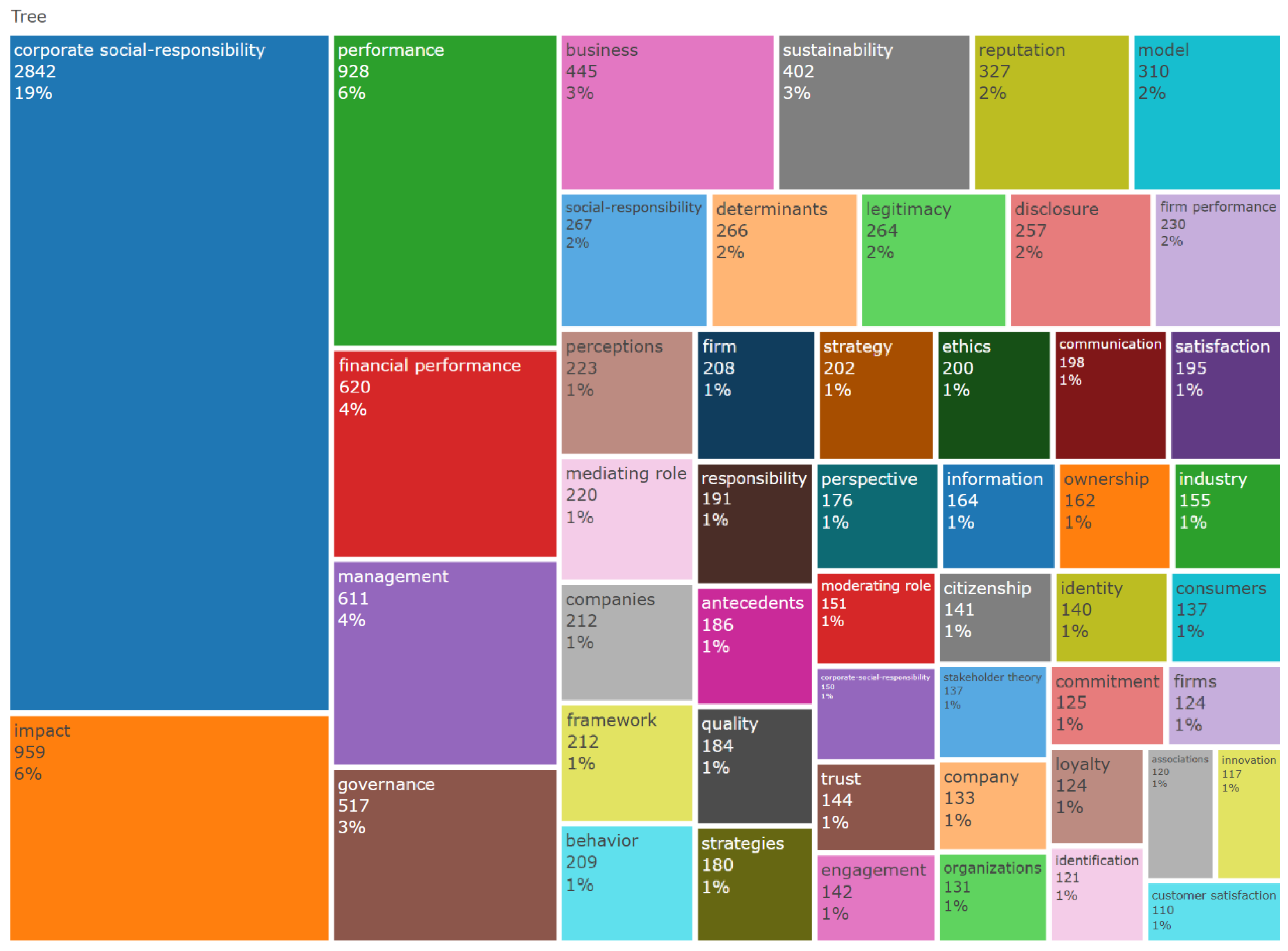

43]. An analysis of articles within the Web of Science database revealed that between 1996 and 2025, there were 5211 publications in the field of CSR that included the term CSR in their titles. This indicates that the true number of articles in this area likely exceeds this figure. The study identified 9741 authors who contributed to these publications, and it is notable that the annual production of articles has increased by 6.37 percent.

Table 1 illustrates the yearly publication numbers, while

Figure 1 depicts the rising trend in article production.

The keywords of the studies in the CSR field show that most of these articles examined the effects of CSR. As shown in

Figure 2, 6% of these keywords were “impact”, 6% were “performance”, and 4% were “financial performance”. This image shows the researchers’ low attention to corporate motivations to apply CSR strategies. As can be seen in

Figure 2, even at the 1% level, we cannot find keywords such as motivation or driver.

Hu et al. [

4] indicated that CSR positively and significantly influences BMI. In their paper, they outline three reasons that illustrate how CSR can foster innovation within a BM.

The first reason is that CSR may result in adjustments and the creation of new value propositions, which leads to BMI. Companies that adhere to CSR issues try to respond to the social concerns of stakeholders by expanding the social features of their products and services and their value activities. In this way, these companies adjust their existing values or create new values. This work also leads to an increase in the company’s reputation, which means that stakeholders participate in adjusting the existing value or creating new value in the digital era.

The second reason is that CSR can lead to BMI through its impact on new business opportunities and strategies. Companies committed to CSR can create new opportunities by responding to issues that accelerate the decrease in old industries and promote the emergence of new industries. This causes companies to abandon their previous BMs and turn to creating and developing new BMs. Also, paying attention to social issues may result in the creation of new business strategies, as companies may need to switch to new BMs and abandon their previous and old BMs to coordinate their performance with their new strategies.

Thirdly, CSR may enhance the CEO’s willingness to take risks, potentially leading to BMI. CSR boosts the CEO’s risk-taking tendencies and positively influences their motivations. As the risk-taking actions of the CEO impact BMI, and implementing BMI is closely tied to the CEO’s leadership and backing, it can be inferred that CSR fosters BMI by reinforcing the CEO’s motivations for risk-taking.

2.3. The Mediating Effect of BMI Between CSR and Firm Performance

Overall, the definition of FP varies and can be viewed from multiple perspectives; as a result, in most research, each researcher defines this concept according to the purpose of their research. The company’s performance can be measured according to things like return on equity (ROAE) [

6,

44].

Small and medium-sized companies face different challenges in different sectors. These challenges include things such as the small scale of operations, limited access to various resources, and so on. These factors lead to the slow growth of SMEs; as a result, the managers of these companies turn to BMI. As a result, while some companies innovate their products and services, SMEs search for opportunities for innovation in things such as their organizational processes [

8]. Some research investigated the relationship between BMI and FP. Anwar [

6] determined the importance of BMI for the success of SMEs. According to the research, there is a direct and meaningful correlation between BMI and the CA and performance of SME companies. In his article, Mohammad Anwar emphasizes the importance of developing an effective business model (BM) for companies to achieve a CA and increase their financial performance.

Cucculelli and Bettinelli [

45] state that updated BMs have the potential to significantly improve FP. The study suggests that businesses that regularly review their business models and adjust them to keep up with the changing market conditions are more prone to attaining lasting growth and profitability. In essence, revising business models enables companies to outpace competitors and respond to constantly changing market trends. Utilizing effective BMI strategies can potentially increase a company’s profitability compared to relying solely on traditional business models [

46]. So, some corporations have shifted their focus from developing new technology to concentrating on BMI [

3]. Research demonstrates that BMI positively influences performance SMEs [

6,

14].

Moreover, in recent years, the impact of CSR on FP, both direct and indirect, has been the subject of investigation by researchers [

4,

39,

47]. Numerous experts have shown a direct connection between CSR and FP [

39,

48,

49,

50].

Rhou [

51] indicated that the impact of CSR on FP is largely dependent upon the attitude of the group’s stakeholders towards CSR. The study found that when the stakeholders of an organization have a positive attitude towards CSR, this has a direct positive impact on the FP.

Le Thanh et al. [

50] investigated the role of CSR in SMEs’ performance in emerging markets (Vietnam) and showed that CSR directly impacts SMEs’ performance. Bahta et al. [

39] indicated that CSR has a significant impact on the performance of SMEs. Looking at several studies performed in the field of CSR, the observations indicate that SMEs engaging in CSR activities may reap various advantages [

8]. Examples of these advantages include, possibly, more profits [

52], increased loyalty from employees [

53], a competitive advantage [

54], an improved business image [

55], and, finally, an improved performance for SMEs [

56,

57]. Hu, Zhang, and Yan [

4] showed that CSR has a direct and significant effect on BMI.

Carroll’s model is renowned for categorizing CSR into distinct dimensions. Carroll [

58] classifies CSR into four levels: economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities [

59,

60,

61,

62]. In recent decades, Carroll’s CSR pyramid has received much attention from researchers and academics, and it has been mentioned in many studies conducted in the field of CSR [

37,

41,

63,

64,

65,

66].

In light of these developments, recent academic contributions have expanded Carroll’s traditional CSR framework to better address the ethical and societal implications of digital transformation. Scholars such as Lobschat et al. [

67] have laid the conceptual groundwork for Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR), framing this as the corporate commitment to mitigate the adverse effects and enhance the positive societal impacts of digital technologies beyond mere legal compliance. Building on this foundation, Herden et al. [

68] explicitly applied Carroll’s framework to the digital domain, using CDR as an extension of CSR that incorporates the ethical opportunities and challenges arising from the use of digital technologies. This includes the imperative to secure a competitive advantage through innovative digital business models (economic responsibility), compliance with data protection regulations and other digital governance norms (legal responsibility), ethical conduct that exceeds legal compliance in the use of digital technologies (ethical responsibility), and voluntary contributions to digital inclusion, knowledge sharing, or digital social innovation (discretionary responsibility). The same authors [

68] proposed a systematic alignment of CDR with the ESG framework, categorizing relevant digital responsibility topics—ranging from data privacy and AI ethics to digital waste and carbon emissions—into environmental, social, and governance domains. This ESG-based classification highlights how the environmental implications of digital infrastructures (e.g., energy use, digital waste, and emissions) are increasingly central to responsible corporate behavior. Following this rationale, this study extends Carroll’s model by introducing environmental responsibility as a fifth responsibility within the CSR framework, contextualized for the digital age. In doing so, it acknowledges the growing importance of environmental concerns in digital strategy and governance, and offers a more comprehensive understanding of CSR as it relates to business model innovation in digitally transformed enterprises.

2.4. Economic Responsibility

According to Carroll’s model, economic responsibility forms the foundation of corporate social responsibility, representing a company’s fundamental duty to be profitable and financially sustainable. Profit generation not only ensures business continuity but also supports the fulfillment of other social responsibilities. This perspective aligns with the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm, which emphasizes that a sustained competitive advantage derives from the effective acquisition, development, and deployment of valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) resources [

69,

70].

In this context, BMI can be seen as a strategic capability that allows firms to reconfigure their operations, value propositions, and customer relationships to generate new revenue streams and enhance profitability. The RBV suggests that such innovative configurations, particularly when complex and embedded in organizational routines, can become intangible and difficult-to-replicate resources that contribute to a superior firm performance. For SMEs, which often operate under conditions of resource scarcity and environmental uncertainty, economic responsibility can thus serve as a key driver for engaging in BMI to improve efficiency, create value, and sustain competitiveness.

Generating profit allows companies to cover essential costs—such as raw materials—ensuring their survival in the market [

71]. As Carroll observes, businesses meet customer needs through goods and services, and in return, customers pay for these offerings, which enables companies to earn profits and remain viable. This profitability allows them to invest in future operations and remain competitive.

Seshadri [

72] also emphasizes that companies aiming to develop sustainable strategies must carefully consider income generation, since many socially responsible activities involve financial costs. By embedding mechanisms for profit generation within their business models, organizations can support these activities without compromising their economic stability. Economic responsibility also generates positive externalities for society: as companies become more profitable, they can expand their workforce, increase wages, and contribute more to social initiatives. Financial performance remains one of the key indicators of overall firm performance. Hence, integrating economic responsibility into the business model is essential for achieving sustainable firm success.

Moreover, in today’s digital era, economic responsibility encompasses not only traditional profit-seeking but also digital transformation as a means of achieving long-term viability. Companies leveraging digital business models can benefit from cost reductions, efficiency improvements, and new revenue streams through e-commerce, platform-based services, and digital product offerings [

73]. Digitalization further enables firms to reach broader markets, enhance customer experiences, and optimize operations—thus contributing to financial performance [

74]. Data-driven decision-making, supported by tools such as big data analytics and artificial intelligence, enhances the ability to allocate resources efficiently and maximize returns [

75]. Reflecting this theoretical grounding, the questionnaire items related to economic responsibility focused on the company’s ability to exploit technological innovation to ensure profitability and maintain financial sustainability (see Table 3).

Therefore, considering the central role of economic responsibility and its alignment with both the CSR and RBV perspectives, this research proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. BMI mediates the relationship between economic responsibility and FP in Iranian SMEs.

2.5. Legal Responsibility

Carroll’s second level of CSR is legal responsibility, which emphasizes a company’s obligation to operate within the boundaries of the law and to align its activities with societal rules and governmental regulations. As Carroll notes, companies function within a broader societal framework and are therefore expected to comply with the laws of the society in which they operate, ensuring their conduct is not in conflict with legal norms [

76]. Failure to comply with digital regulations can lead to legal penalties, reputational damage, and financial losses [

77]. Legal responsibility can thus be understood as adherence to the approved laws and formal expectations placed upon businesses.

From the perspective of institutional theory, compliance with legal requirements is a fundamental mechanism through which firms gain legitimacy, minimize risk, and sustain their market presence. This is particularly relevant for SMEs, which are highly sensitive to external pressures, such as regulatory frameworks and industry standards, that shape organizational behavior and strategic choices. Institutional pressures can drive firms to conform to legal norms not merely to avoid sanctions but also to enhance their reputation and maintain stakeholder trust [

78].

In the digital era, legal responsibility extends beyond traditional regulation to include digital compliance—such as adherence to data protection laws, cybersecurity regulations, and digital rights management. Firms must navigate evolving legal frameworks like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and national cybersecurity standards to ensure their digital practices are lawful [

79]. Furthermore, legal responsibility encompasses the protection of intellectual property, which is especially pertinent in digital environments, where software, platforms, and digital content must be legally secured [

80]. Reflecting this dimension, the items in the questionnaire relating to legal responsibility focused on the company’s compliance with laws, legal obligations, and governmental expectations regarding the use of digital technologies (see Table 3).

In the context of BMI, legal responsibility is a strategic driver for firms to adapt their business models in line with changing regulatory requirements and institutional expectations. By embedding legal compliance into the innovation process, companies can reduce the risks of non-compliance, protect their brand reputation, and enhance their organizational performance. This is particularly important in digital business models, where legal oversight plays a critical role in ensuring transparency, data security, and consumer trust [

81]. Moreover, integrating legal considerations into the business model can reinforce a company’s legitimacy in the eyes of stakeholders. Consumers are more inclined to purchase from companies that respect legal norms and demonstrate regulatory compliance [

82]. Digital platforms and technologies also provide firms with tools to manage legal risks more effectively, especially regarding privacy, cybersecurity, and intellectual property rights [

83].

Therefore, by aligning BMI with legal responsibility, SMEs can not only safeguard their operations but can also enhance their competitive advantage and improve firm performance [

84]. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2. BMI mediates the relationship between legal responsibility and FP in Iranian SMEs.

2.6. Ethical Responsibility

Ethical responsibility emphasizes the importance of conducting business in alignment with the societal expectations of fairness, transparency, and moral conduct [

85]. This includes adhering to ethical norms, upholding good corporate citizenship, and ensuring that business practices align with broader societal values. From a stakeholder theory perspective, companies are accountable to a wide range of stakeholders, including customers, employees, investors, and the broader community, whose interests and values shape the company’s legitimacy and long-term success [

86]. Adhering to ethical standards helps build trust, a valuable, intangible resource that can enhance consumer loyalty and positively influence firm performance [

87].

Moreover, BMI can be viewed through the lens of the dynamic capabilities theory, which suggests that firms must continually adapt and reconfigure their resources to respond to changing stakeholder demands and market conditions [

88,

89]. In this context, incorporating ethical considerations—such as fairness in artificial intelligence, transparency in data usage, and responsible marketing practices—into the business model helps companies build trust with their stakeholders and differentiate themselves in competitive markets. Ethical behavior in digital environments is particularly important, as consumers increasingly prioritize companies that handle their personal data responsibly and ensure fairness in AI applications [

90]. Ethical AI governance, which includes addressing algorithmic biases and ensuring transparency in automated decision-making, is essential for maintaining trust and avoiding reputational damage [

91]. Similarly, responsible digital marketing, which avoids manipulative tactics and deceptive advertising, enhances consumer confidence and brand loyalty [

92]. As a result, the questions in the questionnaire discussing this variable focused on issues that addressed the company’s attention to ethical and social expectations, with a focus on maintaining high standards of corporate conduct in the digital age (see Table 3).

By incorporating ethical responsibility into business model innovation, companies can not only respond to stakeholder expectations but also enhance their competitive advantage, safeguard their reputation, and improve firm performance. Therefore, this research proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3. BMI mediates the relationship between ethical responsibility and FP in Iranian SMEs.

2.7. Philanthropic Responsibility

Philanthropic responsibility, as the highest level in Carroll’s CSR pyramid, goes beyond fulfilling ethical and legal obligations by encouraging companies to voluntarily contribute to societal well-being. This responsibility includes actions aimed at improving quality of life in communities, which are not mandated by law or ethical norms. The social exchange theory provides a theoretical basis for understanding this type of responsibility, positing that organizations engage in voluntary actions—such as philanthropy—to build goodwill, enhance their reputation, and develop social capital [

89]. These efforts can lead to competitive advantages by fostering customer loyalty, improving employee satisfaction, and increasing a company’s legitimacy in the eyes of stakeholders [

93].

In the context of BMI, companies that incorporate philanthropic efforts into their business models differentiate themselves in the market by aligning business success with societal progress. These philanthropic actions can serve as a strategic choice to build stronger relationships with customers, communities, and other stakeholders, thereby contributing to long-term sustainability and improved firm performance. In fact, philanthropic activities often act as a mechanism for increasing social capital, which can be translated into increased brand loyalty and higher consumer trust [

94].

Moreover, digital platforms enhance companies’ ability to scale their philanthropic efforts more efficiently, ensuring that they can maximize social impact while maintaining a positive brand image. In the digital era, philanthropic responsibility is increasingly associated with digital initiatives, such as promoting digital inclusion, supporting open-source projects, and leveraging crowdfunding and blockchain technology to improve transparency and resource allocation in philanthropic activities [

95]. Additionally, technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics help organizations identify social needs more effectively and allocate resources efficiently, further enhancing their social impact [

96].

To better assess the alignment between companies’ philanthropic actions and societal expectations, the questionnaire includes questions reflecting the importance of engaging in socially responsible activities that have a positive impact on communities, particularly in the digital context.

Kramer and Porter [

97] argue that companies should leverage their skills, resources, and abilities in ways that contribute to social progress. By integrating philanthropic responsibility into their business models, companies can not only improve their reputation but also foster a sense of purpose and social good, which can attract more customers and enhance employee engagement [

98]. Digital tools enable businesses to increase the effectiveness of their philanthropic initiatives, thereby expanding their ability to influence positive social change. Therefore, this research proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4. BMI mediates the relationship between philanthropic responsibility and FP in Iranian SMEs.

2.8. Environmental Responsibility

Environmental responsibility, as an additional level in Carroll’s CSR model, emphasizes that companies should proactively manage their environmental impact, going beyond mere compliance with legal requirements. The natural resource-based view (NRBV) offers more information in this context, suggesting that firms that focus on environmental sustainability can create long-term competitive advantages by exploiting green innovations, reducing resource dependence, and improving operational efficiencies [

99,

100]. By focusing on sustainable resource use and minimizing environmental harm, companies can not only mitigate negative impacts but also enhance their overall performance.

In terms of BMI, integrating environmental responsibility into a company’s core operations plays a crucial role in achieving sustainability goals. For example, adopting sustainable business models that prioritize energy-efficiency, eco-friendly products, and waste reduction can lead to cost savings and improved profitability. This strategy allows firms to stay competitive while contributing to the greater good. In the digital era, technologies such as big data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), and blockchain can be leveraged to monitor and reduce environmental footprints, further supporting sustainable business practices. For example, AI-driven predictive models can help optimize energy usage in production, while blockchain can ensure transparency in the supply chain, reducing environmental waste.

Moreover, businesses that emphasize environmental responsibility through BMI are likely to attract environmentally conscious consumers and enhance their market reputation, ultimately improving firm performance. Digital tools also empower firms to manage environmental practices more efficiently, ensuring that they remain competitive while contributing positively to the environment. This integration of environmental practices into digital operations reflects an important aspect of modern business models that both safeguard the planet and drive profitability.

This is particularly crucial as firms navigate the complexities of digital transformation. As companies increasingly rely on digital tools, it is imperative that they manage the environmental impact of their digital operations, especially in relation to the energy consumption, electronic waste (e-waste), and carbon emissions associated with data centers and cloud computing [

101]. The focus on environmentally friendly digital practices ensures that organizations are not only benefiting from the efficiencies offered by digital technologies but are also committed to minimizing their ecological impact.

The questions in the questionnaire related to environmental responsibility in this study reflect the growing recognition of environmental concerns in the digital age and underscore the importance of integrating sustainable practices into business models (see Table 3).

Bocken et al. [

100] stress that businesses will need to adopt new models to significantly reduce the negative environmental impacts of their operations and generate positive effects on the community and the environment. In fact, companies that prioritize environmental issues in their business models, especially in the digital era, can differentiate themselves and build a reputation as responsible corporate citizens. Additionally, as Jaiswal and Singh [

102] note, customers increasingly prioritize companies that pay attention to environmental sustainability when making purchasing decisions. This consumer preference for environmentally responsible firms enhances sales and, in turn, improves financial performance. Therefore, this research proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5. BMI mediates the relationship between environmental responsibility and FP in Iranian SMEs.

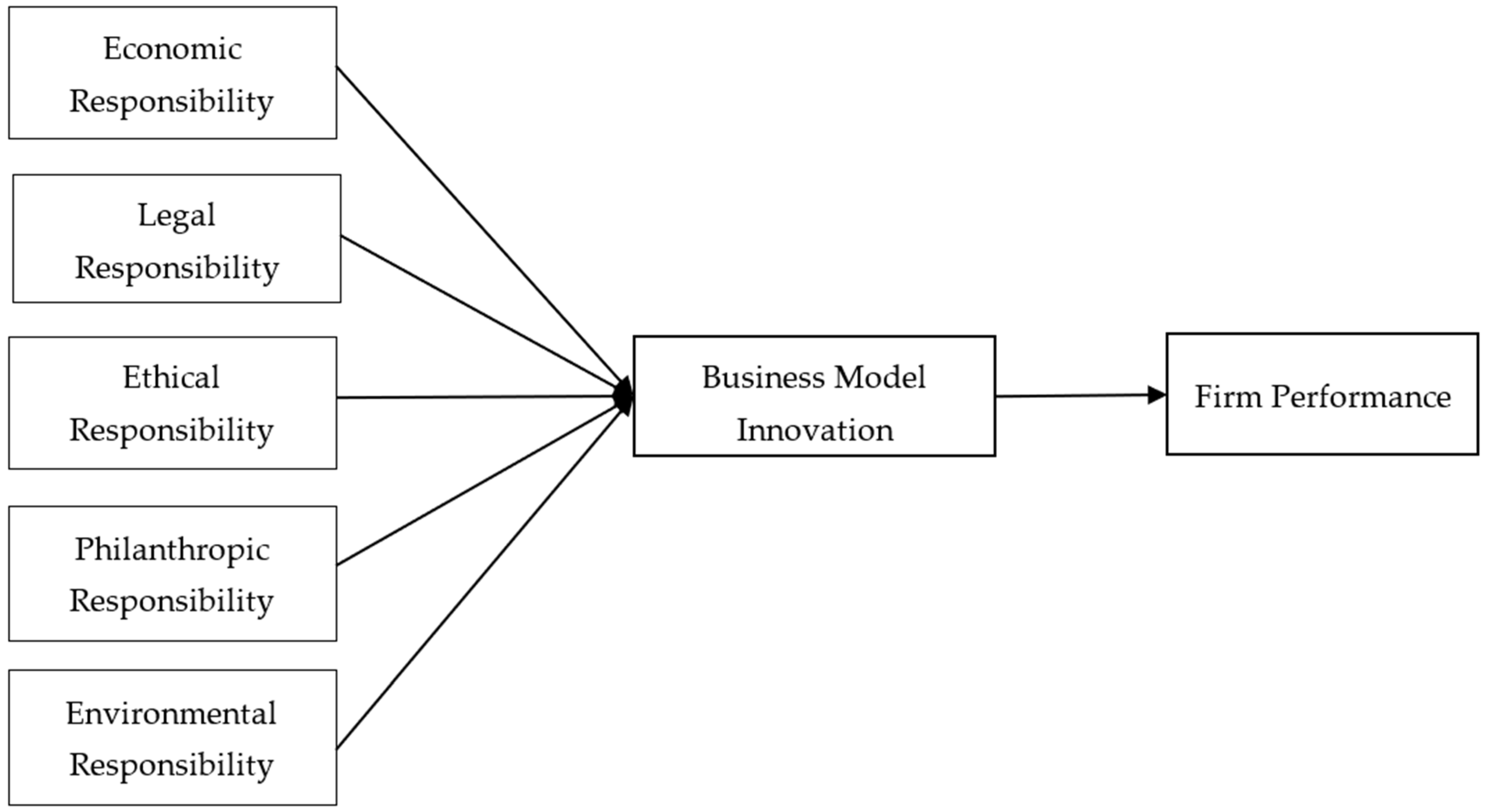

2.9. Conceptual Model

The conceptual model includes aspects of CSR, BMI, and FP.

Figure 3 exhibits our proposed framework for testing the six hypotheses.

As shown in the figure, the conceptual model proposed in this study positions responsibility imperatives—economic, legal, ethical, philanthropic, and environmental imperatives—as antecedents that influence BMI, which, in turn, affects firm performance. Rather than suggesting that BMI is exclusively driven by responsibility concerns, the model emphasizes the mediating role of BMI in translating these various dimensions of corporate responsibility into enhanced organizational outcomes. While the strategic management and entrepreneurship literature often highlights other factors, such as technological changes, competitive dynamics, and market shifts, as central drivers of BMI [

103,

104], our framework recognizes that responsibility imperatives increasingly shape and intersect with these traditional factors. For example, technological advancements frequently raise ethical or environmental concerns that prompt firms to innovate responsibly; competitive positioning is now influenced by stakeholder expectations related to sustainability and transparency; and market demand is often shaped by the heightened consumer awareness of social and environmental issues. Within this evolving landscape, responsibility imperatives act as critical catalysts that direct and condition how firms approach business model innovation. By framing these responsibilities as inputs into the innovation process, our model highlights their strategic relevance and the need to understand how they contribute—through BMI—to long-term firm performance.

3. Methodology

3.1. Choice of Research Design

This research used a quantitative approach to analyze the connection among CSR aspects, BMI, and FP in the digital era. Various factors make a quantitative approach more appropriate for this study. First and foremost, through using this method, we can research a substantial quantity of participants, which increases the validity of the findings. The integration of quantitative data significantly enhances the efficiency of the analysis process. This method enables a thorough investigation of the relevant factors. Furthermore, employing a quantitative framework supports the systematic evaluation of hypotheses, which in turn leads to the generation of robust and trustworthy conclusions [

105].

In accordance with the research aim, the statistical population was Iran’s SME companies. It should be noted that each country has its own definition of what constitutes an SME. Most SME definitions for different countries require SMEs to have the same number of employees. In most of these definitions, it is stated that SME companies have a maximum of 250 employees (such as the definitions provided by Somalia, India, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Mexico). For this reason, the research sample was Iranian SME companies (innovative companies with a maximum of 250 employees). Considering that, for the purposes of this research, it was necessary to gather information from individuals who possess proper information about the strategies and policies of the companies, the data were gathered from company owners or senior managers.

There are many reasons that SMEs were used in this study. The first reason is the role of SMEs in creating employment in Iran. Iran is one of many countries struggling with an unemployment problem. SMEs constitute more than 90 percent of the total number of companies in Iran and make a significant contribution to employment creation. These companies create extensive job opportunities in the manufacturing, service, agricultural, and technology sectors and help reduce unemployment. The second reason is that more people are inclined to establish small and medium-sized companies as they require less capital. The third reason (and perhaps one of the most important reasons) is that this study examines the mediating role of BMI between CSR dimensions and company performance. Therefore, this research is related to the role of SMEs in innovation and research and development. These companies act as innovation centers in many industries due to their flexibility and ability to quickly adapt to market changes. Many knowledge-based companies in Iran are considered SMEs and play a key role in the development of new technologies and products. Furthermore, it should be noted that SMEs are the engine of economic growth in the sectors of entrepreneurship, job creation, and the development of deprived areas. These companies help reduce economic dependence on large and state-owned industries and strengthen local production. Also, the high diversity of small businesses strengthens economic competition and dynamism. Finally, it should be noted that, in recent years, special attention has been paid to knowledge-based companies in Iran, and, as mentioned, many knowledge-based companies in Iran are considered SMEs.

The measurement scales employed for the constructs were grounded in prior research and modified to suit the research context in Iran. Notably, the original questionnaire items were in English. The document was translated into Farsi (Persian) to address cultural differences and ensure transparency.

Convenient sampling was employed to collect the study samples. As the questionnaires are distributed among managers, which can be very difficult to access, this research used the convenient sampling method. Although convenience sampling inherently limits the generalizability of the research findings, there were several factors ensuring the relevance of the selected population and enhancing the contextual validity of this study. The target population consisted of managers of SMEs in Iran—an important economic and strategic sector of the national economy. As stated by the

Financial Tribune (2021), SMEs in Iran contribute significantly to employment and industrial production, representing approximately 99% of all businesses and accounting for 60–70% of private-sector employment, and they play a critical role in innovation and economic resilience, especially in the face of market volatility and international sanctions. The study cohort provides detailed insights into how CSR dimensions affect BMI and FP in a highly dynamic and resource-constrained environment. Further, the managers can provide detailed and strategic insight into the CSR practices and innovation activities in their companies. The involvement of these managers ensured that the collected data provided informed perspectives on the organizational behavior and decision-making processes. Since this elite group is difficult to access, convenience sampling presented an adequate means of collecting information while ensuring the relevance and richness of the information collected. Moreover, in terms of management position, the questionnaires in this study were distributed among four groups (owners, senior managers, middle managers, and operations managers). This provided us with more accurate results and included the views of different management levels. Furthermore, the study encompassed SMEs from various industries, with five sectors each representing over 10% of the sample (

Table 2), reflecting diverse environmental and industry-specific factors. Also, the companies in this study differed in size as well as in the number of employees.

Data for this research were collected through face-to-face coordination with various Iranian SMEs across different industries. Data were collected in the spring and summer of 2023. A total of 652 surveys were distributed to the companies’ highest-ranking employees, including owners, senior managers, middle managers, and operations managers. Out of the distributed questionnaires, 517 were completed, resulting in a completion rate of 79.29%. Of these completed questionnaires, 483 were deemed valid for further analysis.

3.2. Questionnaire and Measures

The scales utilized for measuring the constructs in this study were meticulously developed based on a thorough examination of the existing literature. Additionally, they were carefully adjusted and tailored to align with the specific research context prevalent in Iran, ensuring that the measurements were relevant and applicable to the cultural and social nuances of the region. A survey tool was created for this study, using the available literature as a basis.

The survey instrument used in this study was carefully designed to measure various constructs relevant to CSR, business model innovation, competitive advantage, and firm performance. The questionnaire consisted of multiple sections aimed at gathering demographic information and assessing respondents’ perceptions of the aforementioned constructs.

The first section collected demographic data from the respondents, including their position (e.g., company owner, senior manager, middle manager, or operational manager), type of activity (e.g., production or service), industry (e.g., information and communications technology, financial services, consulting, education and training, or others), number of employees (e.g., up to 10, 10–50, 50–500, or more than 500 employees), and the age of the company (e.g., less than 5 years, 5–10 years, or more than 10 years).

The CSR section of the questionnaire was divided into five dimensions, each measuring different aspects of the company’s CSR practices. The dimensions were economic CSR, legal CSR, ethical CSR, philanthropic CSR, and environmental CSR. Each dimension consisted of three items, measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5). The items for each CSR dimension were adapted from the existing literature to ensure their relevance to the Iranian context, ensuring the measurement was culturally applicable.

The questionnaire also included a section on BMI, focusing on the company’s efforts in using digital technologies to develop new products, markets, resources, processes, and strategic partnerships. The items were based on the work of Hu et al. (2020) [

4], and respondents rated their agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert scale. The section consisted of nine items.

The competitive advantage section measured the company’s perceived strengths relative to its competitors. It included five items that assessed the company’s reputation, market share, product quality, pricing strategy, and time-to-market. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

Firm performance was measured using five items, assessing various aspects, such as market share, customer satisfaction, sales growth, and overall profitability. Respondents rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale, reflecting the company’s performance compared to its competitors.

According to Galbreath and Shum [

106], SEM is more appropriate for CSR research than the traditional regression analysis; therefore, for the purposes of statistical analysis, the conceptual model underwent testing via SEM. SPSS and AMOS software were utilized to analyze the data.

3.3. Data Analysis

Galbreath and Shum [

106] proposed that structural equation modeling (SEM) is more appropriate for CSR research than traditional regression analysis. Consequently, SEM was employed to evaluate the conceptual model in the statistical analysis. Other similar studies in the field of CSR have also used this method to analyze their data. Examples of these studies include those by Omidvar and Lopes [

107], Sardana et al. [

108], and Wang et al. [

109]. To analyze the data, SPSS version 21 and AMOS version 24 software were used.

Data analysis was performed using AMOS version 24, in two stages. CFA was used in the initial stage to estimate and assess the dimensions. CFA is a statistical method that is used to confirm that a group of observed variables has a factor structure. Also, it is the preferred analytical tool for creating and improving measuring tools, analyzing the validity and reliability of a construct, determining a method’s effects, assessing measurement model fit, and verifying the construct fit indices. To evaluate the theories and the model fit, an SEM analysis was carried out in the second stage.

4. Results

Table 1 showcases the companies’ characteristics. Among the 483 responses, 83 (17.2%) were from business owners, 145 (30.0%) from senior managers, another 145 (30.0%) from middle management, and 110 (22.8%) from operations management. Other information about the respondents is provided in

Table 2. According to

Table 2, most of the companies that were reviewed were in the early years of their lives (under 10 years) and most had between 50 and 200 employees.

The test of the measurement model indicated that it fit the data excellently: χ2 = 607.681, df = 329, χ2/df = 1.847, RMSEA = 0.042, PNFI = 0.722, GFI = 0.917, AGFI = 0.897, CFI = 0.913, IFI = 0.914, and TLI = 0.900.

Table 3 displays all factor loadings, Cronbach’s α, composite reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). Before the review, it is essential to highlight that during the data analysis phase, two questions (specifically BMI 1 and BMI 9) were excluded for BMI review due to their incompatibility with the other responses, and inconsistencies in the model were rectified.

Table 2 illustrates that the factor loadings of the measurement model surpass the recommended threshold of 0.5 established by Hair et al. [

110] and are statistically significant. Five items had factor loadings ranging from 4 to 5. According to Guadagnoli and Velicer [

111], factor loadings that are standardized and greater than 0.4 are deemed to be stable. Hence, all the measurement models with factor loadings are statistically significant and standardized. Factor loadings are the correlation coefficients that show how strongly each observed variable (item) is related to its underlying latent variable (construct). A higher factor loading (closer to 1) means a stronger connection. For example, the first question about the economic CSR has a factor of 0.737, which means that it is a good indicator of that structure. As a result, according to the numbers in

Table 3, there is a good correlation between each observed variable (item) and the hidden underlying variable (structure).

The Cronbach’s alphas for three items exceed 0.70, surpassing the recommended threshold according to [

113]. The Cronbach’s alpha for four items was between 6 and 7. An item is deemed reliable if it has a Cronbach’s alpha score above 0.6, with acceptable scores ranging from 0.6 to 0.8, according to Cronbach [

114] and Hajjar [

115]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is a widely used computational coefficient for examining the reliability of questionnaires and scales, according to which the internal compatibility of the questionnaire or research scale can be measured. As a result, the numbers in

Table 3 indicate the internal compatibility of the variables.

According to [

110], a CR above 0.7 suggests a strong level of internal consistency. As indicated in the table, all the values associated with CR exceeded 0.7. Composite reliability is a criterion for measuring the internal compatibility of the scale measurements. This index is very similar to Cronbach’s alpha. In the CR index, the reliability of the structures is not calculated as an absolute value, but shows the correlation of their structures. As a result, the numbers in

Table 3 indicate the internal compatibility of the measures used in this study.

The AVE of each latent construct should be equal to or greater than 0.50 in order to achieve a satisfactory level of convergent validity, as stated by [

116,

117]. The table indicates that the AVE exceeds 0.5 for four variables, while for three variables, the AVE is below 0.5. When the AVE drops below 0.5 but the composite reliability remains above 0.6, the construct is deemed to have acceptable convergent validity according to [

113]. The Ave criterion represents the average variance shared between each structure and its indicators. Simply put, Ave shows the correlation between a structure and its indicators: the greater the correlation, the greater the fit. In fact, this criterion shows how much of each category is integrated. The research tool was therefore shown to have acceptable compatibility.

The numbers related to the assessment of [

118] are presented in

Table 4. HTMT is a way to measure the divergent validity of, or differentiate between, the constituents of each model structure. In accordance with [

118], an HTMT value exceeding 0.90 suggests a lack of discriminant validity. As indicated in

Table 4, all the values associated with this criterion are below this threshold, indicating that the structure of this study has a good divergent validity.

Hypotheses Testing and SEM

The results of the maximum likelihood estimation indicated a strong fit with the data (χ2 = 613.001; df = 329; χ2/df = 1.863; RMSEA = 0.042; PNFI = 0.718; GFI = 0.916; AGFI = 0.896; IFI = 0.910; TLI = 0.896; and CFI = 0.909). All the fitting values of these indices fall within an acceptable range, as evidenced by the numbers.

According to

Table 5, economic responsibility has a direct and considerable relationship with BMI (β = 0.235) (

p > 0.05, but because it is very close to 0.05, we can consider it significant), and also has a positive and significant relationship with FP (β = 0.407,

p < 0.01), and BMI mediates the link between economic CSR and FP (

p < 0.01). Consequently, Hypothesis 1 is upheld.

According to

Table 6, legal responsibility has a significant relationship with BMI (β = 0.323,

p < 0.05), but does not have a considerable relationship with FP (β = 0.138,

p > 0.05). In addition, BMI mediates the link between legal CSR and FP (

p < 0.05). Consequently, Hypothesis 2 is upheld.

According to

Table 7, ethical responsibility has a direct and considerable relationship with BMI (β = 0.226,

p < 0.05), but does not have a positive and considerable relationship with FP (β = 0.036,

p > 0.05). In addition, BMI mediates the connection between ethical responsibility and FP (

p < 0.05). Consequently, Hypothesis 3 is upheld.

According to

Table 8, philanthropic responsibility does not have a positive relationship with BMI (β = −0.211,

p < 0.05), and also does not have a positive and considerable relationship with FP (β = 0.045,

p > 0.05). BMI mediates the connection between philanthropic responsibility and FP (

p < 0.05). Consequently, Hypothesis 4 is upheld.

According to

Table 9, environmental responsibility has a significant relationship with BMI (β = 0.146,

p < 0.01), but does not have a positive and considerable relationship with FP (β = 0.035,

p > 0.05). In addition, BMI does not mediate the connection between environmental responsibility and FP (

p > 0.05). Consequently, Hypothesis 5 is rejected.

It should also be noted that R-square (R2) values show that BMI is 50.5% influenced by CSR dimensions; the remaining 49.5% is attributed to factors outside of this model. These factors could include things like technological change, competitive pressure, and changes in market demand.

5. Discussion

This study investigated how BMI mediates the relationship between CSR and FP in the digital context, offering strategic insights that are particularly relevant for Iranian SMEs. The prior literature has emphasized that digital transformation reshapes the CSR–innovation nexus, where digital technologies act as both enablers and amplifiers of CSR-driven business model changes [

119]. Consistent with these views, our findings confirm that economic CSR exerts a significant direct influence on both BMI and FP, reinforcing the argument that digitally oriented firms emphasizing economic responsibility leverage technological tools to innovate and capture new value [

120]. This suggests the direct role of economic responsibilities—profitability, cost efficiencies, and value creation for shareholders—in determining strategic and operational efficiency for companies. The indirect role of the economic CSR on BMI implies that as business firms prioritize more economic responsibilities, they become more innovative in their approach to creating, bringing, and attracting investment. Economic CSR prompts companies to compete, explore new revenue streams, and refine their business models to meet evolving market demands. This aligns with the belief that financially stable and economically responsible companies possess the strategic resources and motivation required to engage in innovation initiatives [

121]. In addition, the significant impact of the economic CSR on FP shows that companies involved in responsible economic measures tend to achieve better performance results. This finding corresponds to the theory of stakeholders and resource-based views, which shows that meeting economic expectations increases the trust between investors, customers, and partners, and ultimately contributes to superior financial and operational performance. These findings emphasize the importance of incorporating economic CSRs into the main business strategies. Not only does BMI undergo an innovative transformation, this also leads to tangible improvements in the performance of the company. This reinforces the notion that economic responsibility is not only an essential component of CSR; it also serves as a catalyst for sustainable growth and provides a competitive advantage.

Legal CSR also has a strong impact on BMI, aligning with studies highlighting how digital compliance tools, such as AI-driven monitoring and blockchain for transparency, can convert regulatory adherence into opportunities for innovation [

120]. Although no direct impact on FP was observed, the mediating role of BMI indicates that the innovative use of digital compliance strategies enhances operational efficiency and stakeholder legitimacy, which indirectly translates into performance benefits. The significant relationship between legal responsibility and BMI shows that companies that adhere to organizational laws, regulations, and standards are likely to make innovative changes to their business models. Legal adaptation can lead companies to re-configure their operations and structure to meet regulatory expectations and thus innovate. For example, the evolving legal frameworks related to sustainability, labor rights, or data protection may force companies to innovate in terms of their value propositions or processes to remain consistent and competitive. However, the lack of a significant direct relationship between the legal CSR and the FP indicates that merely legal standards do not necessarily lead to an improvement in performance results. This finding corresponds with earlier research showing that legal adaptation, while essential for legitimacy and risk management, does not inherently offer a competitive advantage or performance improvement unless it is strategically used [

58]. The intermediary role of BMI highlights a vital mechanism through which legal responsibility can ultimately affect performance. When companies respond to legal requirements with active innovation—rather than through minimal compliance—they can turn potential restrictions into strategic opportunities. Through aligning legal responsibilities with changes in their innovative business model, companies better position themselves to increase operational efficiency, customer satisfaction, and market adaptation, which in turn help improve performance. This insight emphasizes the importance of managers not only fulfilling legal norms but also interpretating such responsibilities as drivers of innovation. It also emphasizes the strategic value of BMI as a bridge between external organizational pressures and internal performance results.

Ethical CSR significantly influences BMI, aligning with the research that found that digital ethics and responsible innovation are pivotal in reshaping business practices [

122]. While its direct effect on FP remains non-significant, ethical CSR, when integrated into BMI, enhances stakeholder trust and competitive positioning in digital ecosystems, confirming that a strong ethical foundation supports long-term digital value creation.

The direct impact of ethical CSR on BMI shows that firms that go beyond legal adaptation and actively consider ethical commitments, such as fairness, transparency, environmental supervision, and stakeholder well-being, are likely to pursue innovative commercial models. Ethical considerations often force organizations to revise their traditional ways and adopt sustainable, inclusive, and more responsible approaches to create value. Such preventive ethical behavior can stimulate the configuration of products, services and delivery systems in ways that are better aligned with social expectations. However, the lack of a direct and positive relationship between ethical CSR and FP shows that moral action does not automatically lead to superior financial or operational results. This finding is in line with previous studies showing that ethical initiatives may require significant investment and may not bring immediate financial returns, especially when they are not integrated with the main goals of the business [

122,

123]. In some cases, the benefits of ethical actions—including advanced fame, employee morale, or customer loyalty—may only be revealed over a longer period. The intermediary effect of the BMI is particularly enlightening. This means that ethical responsibilities can play a role in improving performance through prompting innovative developments to the business model. By incorporating ethical values within their strategic framework through innovation, companies can distinguish themselves, build stakeholders’ trust, and adapt more effectively to social and market changes. In essence, ethical responsibility strengthens performance when it is translated to meaningful innovation. This reinforces BMI’s strategic importance as a way of translating ethical obligations into tangible commercial value. It also shows that firms should not regard ethical CSR as a cost or commitment, but as a catalyst for creative appeal and competitive positioning.

Philanthropic CSR has a significant but negative direct effect on BMI, suggesting that while companies engage in socially benevolent actions, these may not inherently stimulate innovation in business models. This supports the idea that such initiatives—like community support or charitable donations—are often driven by moral or cultural expectations rather than strategic intent. In the context of Iran, this may be partially explained by the cultural and perceptual overlap between philanthropic and ethical responsibilities. In many cases, philanthropic measures are seen as moral extensions of a task rather than distinct strategic initiatives. Jamali and Mirshak [

124] observed that, in developing countries, CSR practices are often grounded in philanthropic actions, without a systematic, focused, and institutionalized approach. Similarly, Ali Aribi and Arun [

125] found that Islamic financial institutions often perceive CSR as a moral obligation, which may not translate into strategic initiatives. As a result, firms may participate in such activities out of social or religious obligations rather than as part of a broader innovation strategy. This blending of ethical and philanthropic CSR aligns with Iranian societal norms, where religious and moral expectations often shape corporate conduct more than market-driven imperatives.

In addition, the lack of a direct and positive relationship between philanthropic CSR and FP implies that these voluntary efforts, while socially admirable, are not yet understood as mechanisms to enhance company performance. This may be due to the lack of a strategic balance between philanthropic initiatives and business goals. When philanthropic efforts are viewed as side activities rather than integrated into the business model, their effect on performance may remain limited or intangible. Islam et al. [

126] noted that in the context of developing countries such as Iran, CSR activities have a significant effect on customer loyalty and brand positioning, suggesting that the strategic integration of CSR can enhance performance.

However, the intermediary role of the BMI in the relationship between philanthropic CSR and FP provides an important insight. This shows that when philanthropic values are significantly integrated into the commercial model of a company—such as through pervasive product development, social-oriented services, or community-based innovation—it is possible to improve performance results. In other words, philanthropic responsibility can support firm success, but only when it is operationalized through innovative and strategic business developments.

Given the current understanding of CSR in Iran—where philanthropic and ethical responsibilities are often blurred—it is essential to distinguish between strategic moral and philanthropic commitments. Educating stakeholders, both in organizations and in society, on the unique role of philanthropic CSR can enhance its perceived value and encourage more purposeful innovation related to social interests.

Environmental CSR was found to significantly drive BMI, in line with work emphasizing the role of digital tools in enabling circular economy practices and environmental transparency [

127]. However, unlike other CSR dimensions, in this study, environmental CSR was not found to significantly affect FP through BMI. This result diverges from some of the literature, which suggests a positive link between environmental initiatives and financial outcomes [

128]. This divergence suggests that while digital environmental strategies support innovation, they may require a longer period to influence measurable financial gains. This is one of the most distinctive findings of the study and shows that while some Iranian companies are involved in environmentally responsible behaviors that inspire innovation, these efforts have not yet translated into measurable performance benefits. Firstly, environmental initiatives often entail substantial upfront costs with delayed financial returns, deterring SMEs operating under financial constraints from prioritizing such practices [

129]. Iranian SMEs, in particular, face economic challenges, including limited access to capital and high operational costs, leading them to focus on immediate survival and profitability over long-term sustainability investments [

130]. This is consistent with the work of Fahim and Reza [

131] observing that environmental responsibility does not have a significant effect on earnings among polluting companies listed on the Tehran Stock Exchange, implying that environmental initiatives may not yet translate into consistent financial returns. Several factors may contribute to this outcome. In Iran, environmental investments are often perceived as cost centers rather than value-generating strategies. Seyfideli and FarhadTouski [

132] noted that while CSR positively affects FP, the impact of environmental CSR specifically may be limited due to its insufficient integration into core business strategies.

Second, many of these enterprises are in the nascent stages of implementing environmental practices, and the benefits of such initiatives—like cost savings and an enhanced brand reputation—may not yet be apparent [

133]. Additionally, the study’s scope did not encompass the non-financial benefits of environmental CSR, such as increased legitimacy and stakeholder trust, which are crucial in the digital era and can indirectly influence financial outcomes [

134].

Furthermore, there may be a gap between environmental innovation and market readiness. Consumers in developing economies, including Iran, may not yet place a high market value on sustainable characteristics, limiting companies’ ability to convert environmental investments into a competitive advantage or revenue growth. Additionally, insufficient government incentives, limited access to green financing, and a lack of supportive infrastructure may reduce the short-term impact of environmental innovation on performance. Asiaei et al. [

132], in this regard, emphasized the need for well-aligned management control mechanisms to effectively translate CSR strategies into organizational performance.

Furthermore, systemic issues—such as weak government incentives, limited access to green financing, and an underdeveloped infrastructure—hinder the translation of environmental efforts into financial gains [

123].

The fact that BMI does not mediate the environmental CSR–FP relationship reinforces the idea that while innovation is underway, it lacks a strategic alignment with performance outcomes. This reflects a broader challenge in Iran and similar economies: there is a disconnect between sustainable practices and economic incentives.

This insight emphasizes the need for policy interventions, market training and strategic integration to bridge the gap between environmental responsibility and business performance. For firms, it demonstrates the importance of developing environmental initiatives with closer value strategies. For policymakers, it shows the need for stronger economic incentives for environmental innovation.

Therefore, while certain dimensions of CSR positively influence BMI and FP, the impact of environmental CSR on FP appears to be more nuanced and context-dependent, particularly within the economic and developmental landscape of Iranian SMEs and those within similar economies. Although this study focused specifically on Iranian SMEs, in fact, many of the contextual challenges identified—such as financial limitations, weak institutional support, and a limited innovation capacity—are also common in other developing economies. The recent literature highlights how digital transformation can enhance CSR implementation by improving transparency, stakeholder engagement, and innovation capacity in resource-constrained settings (e.g., [

133,

134]). However, structural barriers—such as a lack of digital infrastructure or supportive market incentives—can prevent these digital CSR efforts from translating into measurable financial performance [

133]. This may explain why BMI, while positively influenced by CSR efforts, does not uniformly enhance performance outcomes. These findings suggest that, in developing economies, digital CSR must be strategically aligned with business goals and supported by establishing conditions that will drive sustainable value creation.

In sum, this research confirms and extends the existing digital-era CSR literature, demonstrating that CSR dimensions, when digitally enabled, serve as crucial levers for BMI. However, the varying influence on FP across CSR types highlights the need for strategic alignment between digital CSR initiatives and business model design to fully realize the performance outcomes.

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

This study investigated the interplay between CSR dimensions and FP through the mediating role of BMI in the digital era, focusing on Iranian SMEs. It contributes to theoretical development by empirically validating the multidimensional influence of CSR on BMI and FP, expanding Carroll’s CSR pyramid by explicitly integrating the environmental component as a distinct, operationalized factor. By emphasizing the mediation of BMI, this research enriches existing frameworks on innovation-led CSR value creation, particularly in developing economies, where such links remain underexplored.

From a policy perspective, the findings have several actionable implications. Policymakers in Iran and similar developing contexts should create incentive structures that support SME engagement in CSR, particularly through subsidizing innovation programs tied to CSR initiatives. Public policies that promote digital infrastructure and provide targeted funding or tax incentives for environmentally and socially responsible practices could facilitate the transformation of CSR into a competitive advantage through BMI. Regulatory agencies could also strengthen their frameworks for environmental reporting and offer digital tools that make compliance more transparent and scalable, thereby reducing barriers for smaller enterprises.