A Systematic Mapping-Driven Framework for Vetting Participation in Business Ecosystems

Abstract

1. Introduction

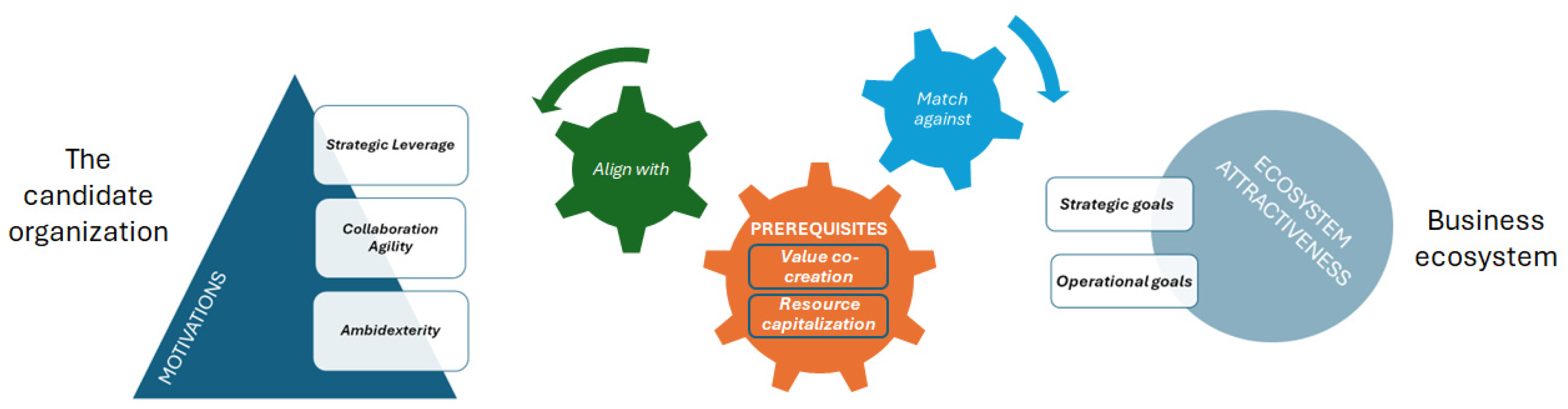

- Core components—three types of factors (motivations, prerequisites, ecosystem attractiveness);

- Guiding logic—the decision-making process must ensure that (a) the motivations of an organization that wants to join a business ecosystem must be filtered through the ecosystem’s minimum requirements for the successful operation of its activities and (b) the motivations must be aligned with the overall strategic appeal and favorable operational environment of a business ecosystem;

- Relationships—prerequisites often lead to refinement of an organization’s motivations; refined motivations are matched against ecosystem attractiveness to highlight strategic/operational fit.

2. Theoretical Background

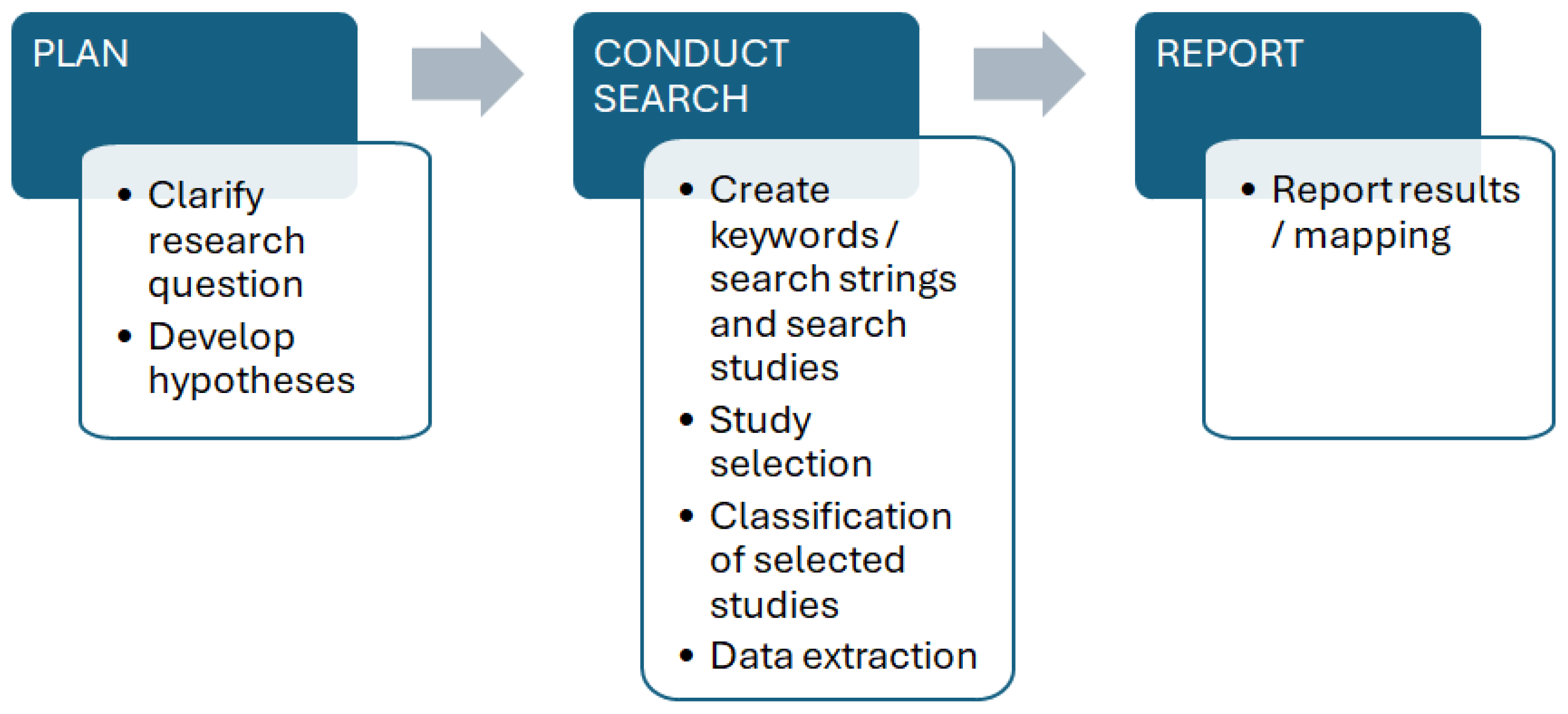

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plan

3.2. Conduct Search

3.2.1. Create Keywords, Search Strings, and Search Studies

- The hypothesis is broken down into individual facets (i.e., population, outcomes), as Kitchenham suggests [51];

- A list of synonyms is created;

- Search terms are identified;

- To obtain a complete list of research artifacts, a backward and forward search is performed;

- While performing the search, various inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied.

3.2.2. Study Selection (Inclusion–Exclusion Criteria)

3.2.3. Classification of the Selected Studies

3.2.4. Data Extraction

- Title;

- Author;

- Publication date;

- Main topic area;

- The source (journal/conference, etc.).

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Motivations

- (a)

- It offers a clear and unambiguous categorization of previously overloaded decision-making factors;

- (b)

- It captures relationships among motivations as a unique three-tiered pyramid of motivations, based on the logic of Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs.

5.2. Prerequisites

5.3. Ecosystem Attractiveness

6. Conclusions

Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Title | Authors | Year | Source | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. A business ecosystem architecture modeling framework | Wieringa R.J., Engelsman W., Gordijn J., Ionita D. [68] | 2019 | IEEE 21st Conference on Business Informatics (CBI) | Ecosystem benefits |

| 2. Analysis of stakeholders within IoT ecosystems | Kar S., Chakravorty B., Sinha S., Gupta M.P. [65] | 2018 | Advances in Theory and Practice of Emerging Markets | Stakeholders’ motivations, IoT ecosystems |

| 3. An analytical framework for an m-payment ecosystem: A merchants’ perspective | Guo J., Bouwman H. [97] | 2016 | Telecommunications policy | Engagement in a particular ecosystem (m-payment) |

| 4. An ecosystem view on third party mobile payment providers: a case study of Alipay wallet | Guo J., Bouwman H. [98] | 2016 | Info | Engagement in a particular ecosystem (Alipay wallet) |

| 5. A systematic literature review for digital business ecosystems in the manufacturing industry: prerequisites, challenges, and benefits | Suuronen S., Ukko J., Eskola R., Semken S. and Rantanen H. [48] | 2022 | CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology | Ecosystem prerequisites, benefits |

| 6. Business ecosystem research agenda: more dynamic, more embedded, and more internationalized | Rong K., Lin Y., Li B., Burstrom T., Butel L., Yu J. [19] | 2018 | Asian business management | Attraction of stakeholders (ecosystem’s perspective) |

| 7. Digital platform ecosystems | Hein A., Schreieck M., Riasanow T., Soto Setzke D., Wiesche M., Bohm M., Krcmar H. [99] | 2019 | Electronic markets | Significance of stakeholders in an ecosystem (relationships, value co-creation) |

| 8. Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem: How digital technologies and collective intelligence are reshaping the entrepreneurial process | Elia G., Margherita A., Passiante G. [76] | 2020 | Technological forecasting and social change | Aspects of ecosystems- motivations |

| 9. Digital empowerment in a WEEE collection business ecosystem: A comparative study of two typical cases in China | Sun Q., Wang C., Zuo L., Lu F. [100] | 2018 | Journal of cleaner production | Activities- positions in an ecosystem- empowerment of suppliers and customers |

| 10. Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem as a new form of organizing: the case of Zhongguancun | Li W., Du W., Yin J. [101] | 2017 | Frontiers of business research in China | Reward distribution as motivation |

| 11. Digitalization of Business Processes of Enterprises of the Ecosystem of Industry 4.0: Virtual-Real Aspect of Economic Growth Reserve | Kraus K., Kraus N., and Manzhura O. [102] | 2021 | WSEAS transactions on business and economics | Prerequisites for digital business ecosystems- I 4.0 |

| 12. Do you need a business ecosystem? | Pidun U., Reeves M., Schüssler M. [3] | 2019 | BCG | Ecosystem benefits |

| 13. Ecosystem Value Creation and Capture: A Systematic Review of Literature and Potential Research Opportunities | Khademi B. [35] | 2020 | Technology innovation management review | Ecosystem attractiveness |

| 14. Entrepreneurial growth in digital business ecosystems: an integrated framework blending the knowledge—based view of the firm and business ecosystems | Chen A., Lin Y., Mariani M., Shou Y., Zhang Y. [69] | 2023 | The journal of technology transfer | Using knowledge as motivation- ecosystem perspective |

| 15. How to Develop a Digital Ecosystem: a Practical Framework | De Leon O.V. [11] | 2019 | Technology innovation management review | How to attract (motivate) participants- ecosystem perspective |

| 16. Innovation ecosystems | Thomas L. and Autio E. [67] | 2020 | Ecosystem dynamics (resilience) | |

| 17. Innovation ecosystems as a service: Exploring the dynamics between corporates & start-ups in the context of a corporate coworking space | Aumüller-Wagner S. and Baka V. [103] | 2023 | Scandinavian journal of management | Value co-creation- attraction of stakeholders |

| 18. Knowledge transfer in open innovation A classification framework for healthcare ecosystems | Secundo G., Toma A., Schiumma G., Passiante G. [67] | 2019 | Business process management journal | Motivations leading to activities-healthcare ecosystems |

| 19. Motives and resources for value co-creation in a multi-stakeholder ecosystem: A managerial perspective | Pera R., Occhiocupo N., Clarke J. [9] | 2016 | Journal of business research | Stakeholders’ motivations |

| 20. Open innovation in SMEs: Exploring inter-organizational relationships in an ecosystem | Radziwon A., Bogers M. [16] | 2019 | Technological forecasting and social change | Drivers for collaboration- innovation (motivations can be excluded and are not stated clearly) |

| 21. Orchestrating ecosystems: a multi-layered Framework | Autio E. [67] | 2022 | Innovation: organization and management | Ecosystem orchestration- ecosystem benefits |

| 22. Prospecting non-fungible tokens in the digital economy: Stakeholders and ecosystem, risk and opportunity | Wilson K.B., Karg A., Ghaderi H. [104] | 2022 | Business horizons | Stakeholders relationships |

| 23. Platform ecosystems as meta-organizations: Implications for platform strategies | Kretschmer T., Leiponen A., Schilling M., Vasudeva G. [105] | 2020 | Strategic management journal | Ecosystem motivations versus traditional organizations |

| 24. Strategies for creating and capturing value in the emerging ecosystem economy | Davidson S., Harmer M., Marshall A. [70] | 2015 | Strategy and leadership | Complexity and orchestration as ecosystem motivations |

| 25. The Nature of the Co-Evolutionary Process: Complex Product Development in the Mobile Computing Industry’s Business Ecosystem | Liu G., Rong K. [76] | 2015 | Group and organization management | Value co-creation benefits (co-vision, co-design, co-creation- > innovation) |

| 26. The resource-based view in business ecosystems: A perspective on the determinants of a valuable resource and capability | Gueler M.S., Schneider S. [106] | 2021 | Journal of business research | Value co-creation and resource acquisition as motivations |

| 27. The role of social platforms in transforming service ecosystems | Letaiafa S.B., Edvardsson B., Tronvoll B. [63] | 2016 | Journal of business research | Emotional motivations (social ecosystems) |

| 28. The Sharing Economy Globalization Phenomenon: A Research Agenda | Parente R.C., Geleilate J.M.G., Rong K. [71] | 2018 | Journal of international management | Internationalization as motivation |

| 29. The Transformational Impact of Blockchain Technology on Business Models and Ecosystems: A Symbiosis of Human and Technology Agents | Schneider S., Leyer M. and Tate M. [107] | 2020 | IEEE transactions on engineering management | Ecosystem attractiveness |

| 30. What Is an Ecosystem? Incorporating 25 Years of Ecosystem Research | Bogers M., Sims J., West J. [16] | 2019 | Meeting of the academy management | Goals of ecosystem members, the network of relations between these members, and the interdependence of their respective goals |

References

- Shin, M.M.; Jung, S.; Rha, J.S. Study on business ecosystem research trend using network text analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, M.; Zoletnik, B.; Pidun, U. How to Benefit from Business Ecosystems If You Are Not the Orchestrator? BCH Henderson Institute. 2012. Available online: https://bcghendersoninstitute.com/how-to-benefit-from-business-ecosystems-if-you-are-not-the-orchestrator/#:~:text=Complementors%20contribute%20to%20the%20ecosystem,its%20variety%20and%20drive%20innovation (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Pidun, U.; Reeves, M.; Schüssler, M. Do You Need a Business Ecosystem? Boston Consulting Group. 2019. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/do-you-need-business-ecosystem (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Davidson, L.; Archer, T.; Borchardt, W. Tapping Ecosystems to Power Performance. Forwards Thinking Companies Are Reaping the Benefits of Working Across Industry Boundaries. Are You Ready to Do the Same? Strategy and Business. 2023. A pwc Publication. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/transformation/tapping-ecosystems-to-power-performance.html (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Moore, J.F. Predators and prey: A new ecology of competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacobides, M.G. In the Ecosystem Economy, What’s Your Strategy? The Five Questions You Need to Answer. Harvard Business Review. 2019. Available online: https://hbr.org/2019/09/in-the-ecosystem-economy-whats-your-strategy (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Smith, D. Navigating risk when entering and participating in a business ecosystem. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. Editor. Technol. Evol. 2013, 3, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pidun, U.; Reeves, M.; Schüssler, M. Why Do Most Business Ecosystems Fail? Boston Consulting Group. 2020. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2020/why-do-most-business-ecosystems-fail (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Pera, R.; Occhiocupo, N.; Clarke, J. Motives and resources for value co-creation in a multi-stakeholder ecosystem: A managerial perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4033–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesten, E.; Stefan, I. Embracing the paradox of interorganizational value co-creation- value capture: A literature review towards paradox resolution. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 231–255. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez-de-Leon, O. How to develop a digital ecosystem: A practical framework. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2019, 9, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiplov, A.; Gawer, A. Integrating research on inter-organizational networks and ecosystems. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 92–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.F. The Death of Competition: Leadership and Strategy in the Age of Business Ecosystems; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobides, M.G.; Cennamo, C.; Gawer, A. Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 2255–2276. [Google Scholar]

- Atluri, V.; Miklós, D. Strategies to Win in the New Ecosystem Economy. McKinsey Digital. 2023. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/strategies-to-win-in-the-new-ecosystem-economy (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Bogers, M.; Sims, J.; West, J. What is an ecosystem? Incorporating 25 years of ecosystem research. In Proceedings of the Meeting of the Academy Management, Boston, MA, USA, 9–13 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Escobar, O.; Arzubiaga, U.; de Massis, A. The digital transformation of a traditional market into an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 16, 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Demil, B.; Lecocq, X.; Warnier, V. Business model thinking, business ecosystems and platforms: The new perspective on the environment of the organization. Management 2018, 21, 1213–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, K.; Lin, Y.; Li, B.; Burström, T.; Butel, L.; Yu, J. Business ecosystem research agenda: More dynamic, more embedded, and more internationalized. Asian Bus. Manag. 2018, 17, 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kutsikos, K.; Konstantopoulos, N.; Sakas, S.; Verginadis, Y. Developing and Managing digital service ecosystems: A service science viewpoint. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2014, 16, 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Kutsikos, K.; Mentzas, G. Managing Value Creation in Knowledge-Intensive Business Service Systems. In Knowledge Service Engineering Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kutsikos, K.; Mentzas, G. A Service Portfolio Model for Value Creation in Networked Enterprise Systems. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science: “Towards a Service-Based Internet”; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, R.; Chen, H. Research on influencing factors of platform leadership in business ecosystem. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2022, 13, 370–394. [Google Scholar]

- Confetto, M.G.; Cavucci, C.; Normando, F.A.; Normando, M. Sustainability advocacy antecedents: How social media content influences sustainable behaviours among Generation Z. J. Consum. Mark. 2023, 40, 758–774. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Rong, K.; Mangalagiu, D.; Thornton, T.F.; Zhu, D. Co-evolution between urban sustainability and business ecosystem innovation: Evidence from the sharing mobility sector in Shanghai. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 942–953. [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto, M.; Kajikawa, Y.; Tomita, J.; Matsumoto, Y. A review of the ecosystem concept—Towards coherent ecosystem design. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 136, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Senyo, K.; Liu, K.; Effah, J. Digital business ecosystem: Literature review and a framework for future research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, D.; Maerkedahl, N.; Shi, P. Adopting an Ecosystem View of Business Technology. McKinsey Digital. 2017. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/adopting-an-ecosystem-view-of-business-technology (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Freundt, T.; Jenkins, P.; Kabay, T.; Khan, H.; Rab, I. Growth and Resilience Through Ecosystem Building. McKinsey Digital. 2023. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/growth-and-resilience-through-ecosystem-building (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Lang, N.; von Szczepanski, K.; Wurzer, C. The Emerging Art of Ecosystem Management. Boston Consulting Group. 2019. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/emerging-art-ecosystem-management (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Ringel, M.; Grassl, F.; Baeza, R.; Kennedy, D.; Spira, M.; Manly, J. The Most Innovative Companies 2019. The Rise of AI, Platforms, and Ecosystems. Boston Consulting Group. 2019. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/collections/most-innovative-companies-2019-artificial-intelligence-platforms-ecosystems (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Luo, J.X.; Triulzi, G. Cyclic dependence, vertical integration, and innovation: The case of Japanese electronics sector in the 1990s. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 132, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V. An Empirical Evaluation of a Generative Artificial Intelligence Technology Adoption Model from Entrepreneurs’ Perspectives. Systems 2024, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulgencio, H. Social value of an innovation ecosystem: The case of Leiden Bioscience Park, The Netherlands. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2017, 9, 355–373. [Google Scholar]

- Khademi, B. Ecosystem Value Creation and Capture: A Systematic Review of Literature and Potential Research Opportunities. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 10, 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pidun, U.; Reeves, M.; Zoletnik, B. Are You Ready to Become an Ecosystem Player? Boston Consulting Group. 2022. Available online: https://web-assets.bcg.com/7c/48/42b0517449c6922e0f4812adf13b/bcg-are-you-ready-to-become-an-ecosystem-player-jun-2022.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Jacobides, M.G. Ecosystems for the Rest of Us. Strategy and Business. 2023. Available online: https://www.strategy-business.com/article/Ecosystems-for-the-rest-of-us (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Pelletier, C.; Cloutier, L.M. Conceptualising digital transformation in SMEs: An ecosystemic perspective. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2019, 26, 855–876. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, F.T.C.; Ondrus, J.; Tan, B.; Oh, J. Digital transformation of business ecosystems: Evidence from the Korean pop industry. Inf. Syst. J. 2020, 30, 866–898. [Google Scholar]

- Song, B.; Xu, H.; Zhao, L. Open or Not? Operation Strategies of Competitive eCommerce Platforms from an Ecosystem Perspective. Systems 2022, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidun, U.; Reeves, M.; Zoletnik, B. What Is Your Business Ecosystem Strategy? Boston Consulting Group. 2022. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2022/what-is-your-business-ecosystem-strategy (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Ramezani, J.; Camarinha-Matos, L.M. A collaborative approach to resilient and antifragile business ecosystems. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 162, 604–613. [Google Scholar]

- Ramezani, J.; Camarinha-Matos, L.M. Approaches for resilient and antifragility in collaborative business ecosystems. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 151, 119846. [Google Scholar]

- Floetgen, R.J.; Strauss, J.; Weking, J.; Hein, A.; Urmetzer, F.; Böhm, M.; Krcmar, H. Introducing platform ecosystem resilience: Leveraging mobility platforms and their ecosystems for the new normal during COVID-19. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 304–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsikos, K.; Kontos, G. Enabling Business Interoperability: A Service Co-creation Viewpoint. In Enterprise Interoperability V; Poler, R., Doumeingts, G., Katzy, B., Chalmeta, R., Eds.; Springer: London, UK; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kutsikos, K.; Kontos, G. A Systems-based Complexity Management Framework for Collaborative E-government Services. Int. J. Appl. Syst. Stud. 2011, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bithas, G.; Sakas, S.; Kutsikos, K. Business Transformation Through Service Science: A Path for Business Continuity. In Procedia—Social and Behavioral Science, Proceedings of the 4th International Conference in Strategic Innovative Marketing, Madrid, Spain, 1–4 September 2014; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 175, pp. 439–446. [Google Scholar]

- Suuronen, S.; Ukko, J.; Eskola, R.; Semken, R.S.; Rantanen, H. A systematic literature review for digital business ecosystems in the manufacturing industry: Prerequisites, challenges, and benefits. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2022, 37, 414–426. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, F. Work and the Nature of Man; World Publishin: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson, B.; Skålén, P.; Tronvoll, B. Service systems as a foundation for resource integration and value co-creation. In Special Issue–Toward a Better Understanding of the Role of Value in Markets and Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2012; pp. 79–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Technical report; EBSE Technical Report EBSE; Keele University: Keele, UK; Durham University: Durham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, K.; Vakkalanka, S.; Kuzniarz, L. Guidelines for conducting systematic mapping studies in software engineering: An update. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2015, 64, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, K.; Feldt, R.; Mujtaba, S.; Mattsson, M. Systematic mapping studies in software engineering. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, Bari, Italy, 26–27 June 2008; Volume 17, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fauzi, S.S.M.; Bannerman, P.L.; Staples, M. Software configuration management in global software development: A systematic map. In Proceedings of the 17th Asia Pacific Software Engineering Conference (APSEC) IEEE, Sydney, Australia, 30 November–3 December 2010; pp. 404–413. [Google Scholar]

- James, K.L.; Randall, N.P.; Haddaway, N.R. A methodology of systematic mapping in environmental sciences. J. Collab. Environ. Evid. 2016, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.V.; Walsh, J.C.; Sutherland, W.J. Organizing evidence for environmental management decisions: A ‘4S’ hierarchy. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014, 29, 607–613. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M.I.S.; Lima, G.F.B.; Loscio, B.F. Investigations into data ecosystems: A systematic mapping study. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2019, 61, 589–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastropetrou, M.; Bithas, G.; Kutsikos, K. Digital Transformation in the Luxury Industry—A Systematic Mapping Study. In Proceedings of the 12th EuroMed Academy of Business Conference, Thessaloniki, Greece, 18–20 September 2021; pp. 731–746. [Google Scholar]

- Mastropetrou, M.; Bithas, G.; Kutsikos, K. Towards a Theory of Motivations and Roles in Business Ecosystems. In Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Pafos, Cyprus, 15–16 September 2022; Volume 17, pp. 351–360. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Maglio, P.P.; Akaka, M.A. On Value and Value Co-Creation: A Service Systems and Service Logic Perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lappi, T.; Haapasalo, H.; Aaltonen, K. Business ecosystem definition in built environment using a stakeholder assessment process. Management 2015, 10, 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B.; Brereton, O.P.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Bailey, J.; Linkman, S. Systematic literature reviews in Software engineering- A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2009, 51, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letaifa, S.B.; Edvardsson, B.; Tronvoll, B. The role of social platforms in transforming service ecosystems. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1933–1938. [Google Scholar]

- Autio, E. Orchestrating ecosystems: A multi-layered framework. Innov. Organ. Manag. 2022, 24, 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kar, S.; Chakravorty, B.; Sinha, S.; Gupta, M.P. Analysis of Stakeholders within IoT ecosystem. In Digital India, Advances in Theory and Practice of Emerging Markets; Kar, A., Sinha, S., Gupta, M.P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Chapter 15; pp. 251–276. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, G.; Margherita, A.; Passiante, G. Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem: How digital technologies and collective intelligence are reshaping the entrepreneurial process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119791. [Google Scholar]

- Secundo, G.; Toma, A.; Schiuma, G.; Passiante, G. Knowledge transfer in open innovation: A classification framework for healthcare ecosystems. Bus. Process Manag. 2019, 25, 144–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wieringa, R.J.; Engelsman, W.; Gordijn, J.; Ionita, D. A business ecosystem architecture modeling framework. In Proceedings of the IEEE 21st Conference on Business Informatics (CBI), Moscow, Russia, 15–17 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.; Lin, Y.; Mariani, M.; Shou, Y.; Zhang, Y. Entrepreneurial growth in digital business ecosystems: An integrated framework blending the knowledge-based view of the firm and business ecosystems. J. Technol. Transf. 2023, 48, 1628–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, S.; Harmer, M.; Marshall, A. Strategies for creating and capturing value in the emerging ecosystem economy. Strategy Leadersh. 2015, 43, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Parente, R.C.; Geleilate, J.M.G.; Rong, K. The sharing economy globalization phenomenon: A research agenda. J. Int. Manag. 2018, 24, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar]

- Postmes, T. A social identity approach to communication in organizations. In Social Identity at Work: Developing Theory for Organizational Practice, 1st ed.; Haslam, S.A., Knippenberg, D.M., Platow, J., Ellemers, N., Eds.; Psychology Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003; pp. 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Siano, A.; Vollero, A.; Confetto, M.G.; Siglioccolo, M. Corporate communication management: A framework based on decision-making with reference to communication resources. J. Mark. Commun. 2013, 19, 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- Valkokari, K. Describing network dynamics in three different business nets. Scand. J. Manag. 2015, 3, 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Awano, H.; Tsujimoto, M. The Mechanisms for Business Ecosystem Members to Capture Part of a Business Ecosystem’s Joint Created Value. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Rong, K. The Nature of the Co-Evolutionary Process: Complex Product Development in the Mobile Computing Industry’s Business Ecosystem. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 809–842. [Google Scholar]

- Siano, A.; Confetto, M.G.; Vollero, A.; Covucci, C. Redefining brand hijacking from a noncollaborative brand co-creation perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022, 31, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bithas, G. A New Business Transformation Model for Service Ecosystems. Ph.D. Thesis, Business School, University of the Aegean, Mytilene, Greece, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Galvagno, M.; Dalli, D. Theory of Value Co-Creation: A Systematic Literature Review. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2014, 24, 643–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketonen-Oksi, S.; Valkokari, A. Innovation Ecosystems as Structures for Value Co-Creation. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2019, 9, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F.; Morgan, F.W. Historical perspectives on service-dominant logic. In The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate and Directions; Lusch, R.F., Vargo, S.L., Eds.; M.E. Sharpe Inc.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Järvi, H.; Kähkönen, A.K.; Torvinen, H. When value co-creation fails: Reasons that lead to value co-destruction. Scand. J. Manag. 2018, 34, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, M.; Kleinaltenkamp, M. Property Rights Design and Market Process: Implications for Market Theory, Marketing Theory, and SD Logic. J. Micromarketing 2011, 31, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Morgan, R.M. The comparative advantage theory of competition. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.B.; Madhavaram, S. Multinational enterprise competition: Grounding the eclectic paradigm of foreign production in resource-advantage theory. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2012, 27, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. The Logic of Open Innovation: Managing Intellectual Property. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2005, 45, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A.; Santoro, G.; Papa, A. Ambidexterity, external knowledge and performance in knowledge-intensive firms. J. Technol. Transf. 2017, 42, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakas, D.; Kutsikos, K. An adaptable decision-making model for sustainable enterprise interoperability. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, C.M.; Hunt, S.D.; Arnett, D.B. Explaining alliance success: Competences, resources, relational factors, and resource-advantage theory. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Shan, J.; Boutalikakis, A.; Tempel, L.; Balian, Z. What makes a company ‘future ready’? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2022. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/03/what-makes-a-company-future-ready (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.H. Process Innovation: Reengineering Work Through Information Technology; Harvard Business Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Akaka, M.A.; Vargo, S.L. Technology as an Operant Resource in Service (Eco)systems. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2014, 12, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Bouwman, H. An analytical framework for an m-payment ecosystem: A merchants’ perspective. Telecommun. Policy 2016, 40, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Bouwman, H. An ecosystem view on third party mobile payment providers: A case study of Alipay wallet. Info 2016, 18, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, A.; Schreieck, M.; Riasanow, T.; Soto Setzke, D.; Wiesche, M.; Bohm, M.; Krcmar, H. Digital platform ecosystems. Electron. Mark. Press 2020, 30, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, C.; Zuo, L.; Lu, F. Digital empowerment in a WEEE collection business ecosystem: A comparative study of two typical cases in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Du, W.; Yin, J. Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem as a new form of organizing: The case of Zhongguancun. Front. Bus. Res. China 2017, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, N.; Kraus, K. Digitalization of business processes of enterprises of the ecosystem of Industry 4.0: Virtual-real aspect of economic growth reserves. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2021, 18, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumüller-Wagner, S.; Baka, V. Innovation ecosystems as a service: Exploring the dynamics between corporates & start-ups in the context of a corporate coworking space. Scand. J. Manag. 2023, 39, 101264. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.B.; Karg, A.; Ghaderi, H. Prospecting non-fungible tokens in the digital economy: Stakeholders and ecosystem, risk and opportunity. Bus. Horiz. 2022, 65, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, T.; Leiponen, A.; Schilling, M.; Vasudeva, G. Platform ecosystems as meta-organizations: Implications for platform strategies. Strateg. Manag. J. 2022, 43, 405–424. [Google Scholar]

- Gueler, M.S.; Schneider, S. The resource-based view in business ecosystems: A perspective on the determinants of a valuable resource and capability. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 158–169. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S.; Leyer, M.; Tate, M. The transformational impact of blockchain technology on business models and ecosystems: A symbiosis of human and technology agents. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 67, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar]

| Incentive | Business Ecosystems |

|---|---|

| Motives | Ecosystem stakeholders |

| Reason | Organizational ecosystems |

| Goals | Joining business ecosystems |

| Ecosystem participation |

| Search Strings |

|---|

| “reason” or “goals” and “business ecosystems” “incentive” and “business ecosystems” “business ecosystem” and “needs” “reason” or “goals” and “ecosystem stakeholders” “incentives” and “ecosystem stakeholders” “business ecosystem” and “readiness” “reason” or “goals” and “organizational ecosystems” “incentives” and “organizational ecosystems” “business ecosystem” and “resilience” “reason” or “goals” and “joining business ecosystems” “incentives” and “joining business ecosystems” “reason” or “goals” and “ecosystem participation” “incentives” and “ecosystem participation” |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| Various Perspectives of an Organization About the Benefits of Joining a Business Ecosystem | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| 2 |

| 7 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

| Papers | Motivations | Essential Motivations |

|---|---|---|

| Valdez-de-Leon O., 2019 [11] |

| Reputation enhancement |

| Pera et al., 2016 [9] |

| |

| Autio E., 2022 [64] |

| |

| Kar et al., 2018 [65] |

| Social impact |

| Elia et al., 2020 [66] |

| |

| Letaifa et al., 2016 [63] |

| |

| Secundo et al., 2019 [67] |

| |

| Kar et al., 2018 [65] |

| Diversification |

| Elia et al., 2020 [66] |

| |

| Kar et al., 2018 [65] |

| |

| Valdez-de-Leon O., 2019 [11] |

| Driving consistency |

| Wieringa et al., 2019 [68] |

| |

| Autio E., 2022 [64] |

| |

| Valdez-de-Leon O., 2019 [11] |

| |

| Valdez-de-Leon O., 2019 [11] |

| Shared cognition |

| Pera et al., 2016 [9] |

| |

| Letaifa et al., 2016 [63] |

| |

| Bogers et al., 2019 [16] |

| |

| Secundo et al., 2019 [67] |

| Experimentation |

| Pera et al., 2016 [9] |

| |

| Chen et al., 2023 [69] |

| Mapping practices |

| Pera et al., 2016 [9] |

| |

| Davidson et al., 2015 [70] |

| |

| Valdez-de-Leon O., 2019 [11] |

| |

| Pera et al., 2016 [9] |

| Formalized processes |

| Davidson et al., 2015 [70] |

| |

| Pera et al., 2016 [9] |

| Networking |

| Parente et al., 2018 [71] |

| |

| Wieringa et al., 2019 [68] |

| Continuous learning |

| Pera et al., 2016 [9] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mastropetrou, M.; Kutsikos, K.; Bithas, G. A Systematic Mapping-Driven Framework for Vetting Participation in Business Ecosystems. Systems 2025, 13, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040236

Mastropetrou M, Kutsikos K, Bithas G. A Systematic Mapping-Driven Framework for Vetting Participation in Business Ecosystems. Systems. 2025; 13(4):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040236

Chicago/Turabian StyleMastropetrou, Margaret, Konstadinos Kutsikos, and George Bithas. 2025. "A Systematic Mapping-Driven Framework for Vetting Participation in Business Ecosystems" Systems 13, no. 4: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040236

APA StyleMastropetrou, M., Kutsikos, K., & Bithas, G. (2025). A Systematic Mapping-Driven Framework for Vetting Participation in Business Ecosystems. Systems, 13(4), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040236