Abstract

For high-growth firms, designing and implementing strategies to ensure the long-term sustainability of business models is a key priority. Although these strategies are carefully planned to achieve specific outcomes, these firms also encounter contextual factors inherent to entrepreneurship, as well as the potential negative consequences of operating as small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Consequently, they adapt emergent outcomes to secure positive scaling-up processes. A comprehensive analysis of 69 studies from 1978 to 2023 revealed that 34.8% used sales as the main indicator of high-growth outcomes, 18.8% considered employment to be the most important outcome, and 37.7% incorporated both. The assessment period for these studies spanned three to seven consecutive years. A subsequent review of the existing literature yielded 56 potential new outcomes, emphasising the existence of a diverse array of concepts and metrics with which to assess high-growth performance. The study confirmed sales and positive profits arising during the planning process as strategic outcomes. However, it was also demonstrated that geographical expansion and innovation become emergent outcomes in critical situations. The research also identified that external factors, including an adverse public environment, business context difficulties, and a favourable business environment, may influence the effect of the firm’s high growth.

1. Introduction

SMEs encounter substantial challenges when attempting to expand beyond the initial start-up phase. A primary challenge faced by SMEs is the delineation of their key performance outcomes, which are often reported in various formats within their business model. A substantial body of research has emphasised the pivotal role of high-growth entrepreneurship, as evidenced by the attainment of substantial sales and employment growth. This system of measuring high-growth performance has been in place for over 45 years, since [1] identified that sales should grow by at least 40% and employment by more than 20% over a period of four or five consecutive years. Nevertheless, a recent debate has emerged concerning the most efficacious methods of measuring high firm growth. The [2] has proposed a range of outcomes for consideration, including innovation, export performance, productivity, cost efficiency, profit, market share, patenting, and royalty income. In contrast, scholars such as [3,4] posited that high profitability is a prerequisite for a firm to qualify as high-growth. However, other studies continue to utilise sales [5,6] and employment expansion growth [7,8,9,10] as key outcomes of a high-growth firm (HGF).

A variety of alternative outcome definitions of eligible high-growth firms have been proposed, including those based on the number of high-value acquisitions [11,12] firm value growth [13], return on assets [14], export orientation [15], healthy finances, and organic growth, without the need for alliances or acquisitions [16]. As demonstrated in the seminal work of [2], a positive correlation exists between financial performance and profits, sales, and market share. Additionally, a body of research has emerged on the relationship between patents and R&D investment [17], and sales growth, measured as the log change in the firm’s total sales or turnover, is a significant factor in financial performance [18]. This scenario presents a wide range of possibilities for the design of outcomes in the business models that SMEs could ultimately use to measure their level of high growth.

The findings of various studies are fragmented, primarily due to sector-specific characteristics, the nature of research analysis, firm size and age, innovation, sector, and economic region. This fragmentation is a prerequisite for understanding the diverse components that propel SMEs towards high growth. As [19] asserts, there is a need to consider contingencies in five drivers of high growth: human capital, human resource management, strategy, capabilities, and innovation. However, it is important to note that there are some extrinsic factors that could mitigate the drivers, and these factors are also part of the constructive business ecosystem, with its market reforms and financing programmes that act between the high-growth process and the achievement of rapid sales results as a key performance measure for SMEs [20].

Nevertheless, a systematic theoretical framework for studying high-growth performance and identifying new business model outcomes remains to be developed. Consequently, the present study may indicate a theoretical and empirical gap resulting from an absence of reliable data and patterns when designing strategic, deliberate, and emergent outcomes. The present study adopts an exploratory approach in accordance with the case study methodology, thereby facilitating the development of theoretical frameworks. This approach commences with the formulation of a general objective, underpinned by the interrogation of the “what” or “how” [21]. The following main research question was thus formulated in an attempt to address the existing gap in the theory: “What are the strategic outcomes that the firm must achieve to ensure high-growth in the IT sector and thereby consolidate the sustainability of its business model?” In order to respond to this question, a multiple case study was conducted with 15 small-to-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the IT sector.

Ref. [22] asserted that business models are the equivalent of the scientific method, where one starts with a hypothesis that is approved in the implementation and revised if necessary. According to [23], models commence from the acquisition of learning and exposure, with no requirement for a set of guidelines. However, they determine that norms and standards should become important when paradigms are uncertain. In the business world, it is crucial to understand the significance of business models in achieving strategic objectives [24], driving innovation [25], facilitating diversification [26], and propelling globalisation [27,28]. Additionally, business models play a pivotal role in enhancing operational efficiency and speed [29]. Therefore, external variables can influence the performance of business models, in addition to other individual factors such as the academic profile of the organization and the business model [30]. The present study sets out to explore the strategic outcomes that entrepreneurs in the IT sector in Chile have implemented to ensure the sustainability of the firm’s high-growth business model.

2. Research Design and Methodology

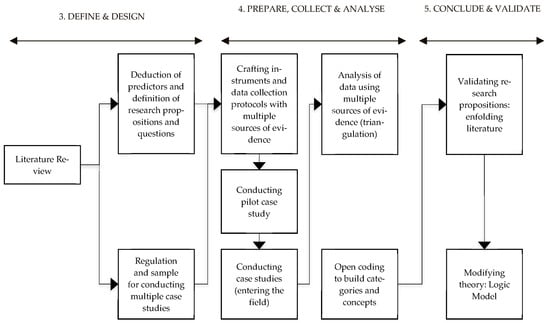

The methodology was developed in three stages. Firstly, the research was defined and designed through an extensive literature review of 69 articles. The objective of this review was to understand the phenomenon and propose three Research Propositions (RPs). Secondly, the instruments were prepared, and data were collected and analysed from multiple sources of evidence in order to validate the findings. Following a rigorous process of validation, the RPs were confirmed, thus bringing the study to a successful conclusion. As illustrated in Figure 1, the adapted methodology of [21,31] incorporates the fundamental activities proposed by [32,33] in three stages for the validation of RPs and the data analysis process. Ref. [34] research expanded upon and adopted these guidelines, emphasizing their role as rigid templates for conducting successful case studies. The researchers noted that these templates have been employed by a considerable number of reviewers and examiners. It is evident that the requisite sample size for a multiple case study has been met, given that the recommendations of [21,35] to complete a minimum of eight to twelve cases, respectively, have been fulfilled. This ensures that the phenomenon can be analysed, thereby facilitating the development of theory and convincing the reader of the general question. It is evident that the method under scrutiny fails to address the variance theory of the data [33]. Consequently, the application of statistical tests becomes unfeasible. The present study adopts a qualitative approach, thus obviating the necessity for mathematical proof, as asserted by [36]: “Lord, I hope that’s not true either, especially when it gets to the point of feeling that we need to include coding reliability statistics in our reporting”.

Figure 1.

The present case study methodology has been adapted from the approaches developed by [21,31,32,33]. This methodology is structured into three key phases to guide the multiple case studies.

3. Define and Design the Multiple Case Study

The initial phase of the methodology entailed a thorough literature review, with the objective of identifying the outcomes employed by IT entrepreneurs to propel their ventures towards accelerated growth. Consequently, parallel activities were developed to identify the variables to construct the model, in conjunction with the research propositions, and to regulate the study sample.

3.1. Literature Review

The phenomenon of high-growth SMEs has been the subject of numerous studies in various contexts. However, a divergence of opinion exists among theoreticians and practitioners regarding the most effective methods of measuring the performance of HGFs. In their study, ref. [37] posited that sales are a pivotal factor in the growth of high-performing firms. It is contended by the researchers that this outcome is more pronounced in the top quantiles compared to the middle or bottom quantiles of the growth distribution. Furthermore, ref. [38] analysis explored the impact on HGF, utilising a range of financial outcomes including “monthly sales, truncated monthly sales, annual sales, sales higher than a year ago, monthly profits, truncated monthly profits, profits in the best month, and the inverse hyperbolic sine of profits”. Conversely, the growth in the number of employees in firms is a proposed outcome to measure the effectiveness of high growth. In this sense, ref. [39] considered the importance of the increase in the number of employees measured five years after the hiring of the first employee. While job creation is an important social and economic outcome for [18], it is important to note that firms are likely to have revenue-focused growth targets, as sales ultimately indicate success in the market. Consequently, while employee growth is directly associated with high firm growth, as suggested by [40], other variables such as innovation are sensitive to their impact on sales and employment growth, according to [17]. Consequently, the results may be correlated, which complicates the standardisation of the criteria.

In order to ensure that the firm achieves high growth in the IT sector and thereby consolidates the sustainability of its business model, the study addresses the primary research question: what are the strategic outcomes that the firm must achieve to ensure high growth in the IT sector and thereby consolidate the sustainability of its business model? The selection of papers was based on previous influential study in this field [19], who also worked with a similarly targeted body of literature to produce impactful findings, with a list of 39 studies from which 27 met the following inclusion criteria: The studies had to include at least one outcome as an indicator of high growth, have a database of at least 1000 companies, use a quantitative methodology, and define a consecutive period of high growth. To expand the list, a further 42 articles that met these four criteria were identified. In an effort to maintain the integrity and relevance of the collected data, a rigorous process of inclusion and exclusion criteria was implemented. The application of these criteria resulted in a reduction in the number of eligible studies; however, it also led to an enhancement in the depth and focus of the analysis. Consequently, the final sample of 69 firms offers pertinent information for the study, including the definition of the establishment period prior to the high growth and the period analysed. The concept of establishment has been overlooked in high-growth research, thus creating a gap in the extant literature, as it fails to provide a taxonomy for the establishment period prior to high growth in the IT sector, which is the most significant growth sector. While the literature reviews the traits and characteristics of HGFs that have grown considerably in recent years, many studies have omitted the importance of identifying critical outcomes. As demonstrated by [40], the significance of elements such as human capital, human resource management, strategy, innovation, and capabilities is substantiated. The study further validates that sales and employment represent pertinent outcomes. However, they do not provide an explanation for the influence of the entrepreneurial context, periods of establishment of the firm prior to high growth, and the different sectors in which the research was conducted. Despite reporting the relevant outcomes for firms to grow rapidly, they do not examine the emergent outcome that arises in adverse situations or obstacles that entrepreneurs constantly face, as reported by [41].

The literature review analysed 69 studies conducted between 1978 and 2023, with a high concentration in the United States (26.1%), followed by the United Kingdom (20.3%), Spain (7.2%), and Sweden (4.3%), with the remainder comprising one or two studies conducted in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Cyprus, and Slovenia. A comprehensive review of extant studies employing international samples, with a particular focus on African and Latin American countries, was also conducted. With regard to the size of the firm, 42.0% of the studies focused on SMEs, 26.1% on small enterprises, 10.1% on large enterprises, 20.3% on all sizes, and 1.4% on medium-sized enterprises only. It can be concluded that SMEs are represented by at least 69.6% of the studies, with approximately half of these papers being carried out principally in the US and the UK.

It is important to note that 34.8% of the studies utilise solely sales growth as a performance outcome to qualify HGF, with average annual growth ranging from 11.0% to 166.3%. Conversely, 18.8% of the studies adopt employment growth as the exclusive performance outcome to qualify HGF, with average annual growth ranging from 10% to 250% over a period of 3 to 10 consecutive years. The research revealed that 37.7% of firms utilise both the annual growth rate of sales and employment as key outcomes to measure the high growth of their firms, considering a range of three to seven consecutive years. In contrast, the remaining 8.7% of studies utilise outcomes that are not limited to sales or employment growth. The following sections will present a thorough review of the extant literature in pursuit of a comprehensive analysis of firm size and sales growth outcomes.

3.1.1. Average Annual Sales Growth (Turnover)

The analysis in this section encompasses 24 studies of small, SME, large, and all firm sizes. The results, presented in Table 1, demonstrate an absence of consistent patterns in average annual sales growth between the different firm sizes, ranging from 20% to 159%. Furthermore, 33% of the reports propose a period of at least three years to consolidate high growth, while 38% propose a period of at least five consecutive years. As is evident in the data, 29% of the sample utilises the average annual growth rate of 20% in sales, while double annual growth is employed by 21%. The preponderance of information derives principally from the United States and the United Kingdom, with 67% of the extant studies being conducted in these countries.

Table 1.

Studies of sales outcomes in consecutive years for small firms.

3.1.2. Average Annual Employment Growth

Thirteen studies were reviewed at this stage, focusing on understanding employability outcomes in high-growth firms. The minimum average annual employment growth ranged from 10% to 250% over a period of two to ten years. The studies primarily concentrated on SMEs with a minimum of two years of operational history. Thirty-one percent of the studies reported average annual employee growth of 10%, while an additional 31% used the rate of 20%. The results confirmed that employee growth is a key outcome for measuring firm performance. Please refer to Table 2 for more information on this outcome.

Table 2.

Studies on employment outcomes in consecutive years.

3.1.3. Average Annual Growth in Both Sales and Employment in Consecutive Years

The analysis of 26 studies revealed average annual growth rates ranging from 5% to 822% for sales and from 5% to 461% for new employment. Small firms and SMEs account for 69% of this sample, which is defined as firms that have been in existence for at least three years. As in the other studies, no pattern or common denominator can be identified that would define the minimum annual growth rate for both outcomes. The results of this summary are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Studies on sales and employment outcomes in consecutive years.

3.1.4. Alternative Outcomes for High Growth

A comprehensive review of the extant literature on the subject yielded 56 novel potential metrics for high growth. During the analysis of 69 cases, these were grouped into five dimensions. Conversely, the existence of limits to high growth has been proposed. As [59] asserted, “slow-growing firms are those with an average annual growth rate of 35% or less”. Ref. [63] recommended that the firm’s past growth history should be considered through “absolute, relative, and composite formulas” [8]. A range of other outcomes were identified to provide a comprehensive overview of the potential actions that could be implemented to provide support to entrepreneurs during the high-growth phase of their firms.

There are a number of ways in which the financial outcomes of a firm can be measured, for example, profit [2,58,70,94,95,96] is a commonly used measure, while earnings [97] and net worth [98] are also frequently analysed. It is possible to measure a number of other outcomes. These include the compound annual rate of return [43] and the average annual rate of return on equity [95]. As demonstrated in the studies of [44,52,53,64,99], the average operating income, return on capital, debt ratio, and revenue have been found to be the most significant outcomes. In order to obtain further insight into the revenue of the firm, a substantial body of evidence has been identified that supports this outcome. This includes works by [18,49,72,76,81,82,100]. In addition, further financial outcomes have been identified, including positive equity [76], average annual growth in wages [77], operating revenue [89], liquidity [89,101], ratios of solvency, cost efficiency, licensing revenues [89], total assets [52,102,103], and fixed assets [40]. Productivity [2], firm value growth [99], and capital financing [104] are also considered important outcomes. Other variants include the calculation of firm sales divided by total assets [52] and cash flow [98,101].

A subsequent outcome identified is innovation, which can be measured in various ways, including rate of flexibility, design flexibility, and product variety [51]. In addition, the following factors should be considered: percentage of sales [53], R&D activities [17,74], the number of new alliances [16,74], and patenting [2,17]. As demonstrated in the relevant literature, new product development [53,74], superior product quality [51], and unique value for customers [105] have been identified as relevant outcomes.

In relation to sales outcomes, the bibliography identifies further variations, including sales from new products [99], sales growth leading to lower employment growth [106], annual sales per employee [42,44], cost of physical assets per sales [45], price [51], new clients [55,107], client retention [55], market share [2,88,98,99], and after sales service [51].

As demonstrated in the extant literature, internationalisation is another outcome that can be measured through rapid internationalisation [50], geographical expansion [15,55], international trade [57], percentage of revenue from foreign markets [61], revenues from internationalization [82], number of export destination countries [10,108], and number of products exported and number of imported products [10].

Finally, alternative human resources outcomes include firm age [91], net new jobs [109], relative and absolute employment growth rates [110], highest average annual increase in absolute employment [111], job destruction [69], and total job supply must be higher in the fourth year than in the first year [65].

3.1.5. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem as a Moderator

The business environment exerts a considerable influence on the performance of SMEs, manifesting in either a favourable or unfavourable manner, as evidenced by the research conducted by [112]. The findings demonstrate how entrepreneurs develop a diverse array of capabilities to capitalise on opportunities that emerge within the environment. However, ref. [113] have found that formal conditions in emerging markets for re-entry entrepreneurs are very limited and focused only on high-growth firms. However, as [114] have identified, there are other forms of benefits emerging within the entrepreneurial ecosystem. The aforementioned factors comprise professional expertise, support for incubators and accelerators, and business networking with research and development for investment in new products and services. The entrepreneurial environment is a complex system influenced by various factors, including culture, economy, society, the venture process, and gender [115]. As [8] observed, it plays a crucial role in fostering high-growth potential by maintaining competitive barriers through legal constraints and regulatory policies. Nonetheless, ref. [116] posited that, for high-growth enterprises, it is imperative to operate within a rapidly expanding industry as opposed to a stable one in order to attain superior liquidity ratios and foster heightened innovation. Ref. [117] posited that the exploitation of ideas within established firms is contingent on an entrepreneurial ecosystem that has the capacity to exert a positive or negative influence on the performance of SMEs during their high-growth process.

3.2. Deduction of Predictors and Definition of Research Propositions and Questions

As demonstrated in extant literature, entrepreneurs encounter persistent challenges in achieving the sustainability of their business models. However, a theoretical gap in understanding the complex interplay between deliberate and emergent outcomes that influence high-growth firms remains. Furthermore, a taxonomy that classifies the various strategic outcomes to ensure high firm growth has not been identified. Three research propositions (RPs) were formulated with the objective of identifying critical outcomes during a regular high-growth process. The RQs were developed to guide the multiple case studies. For each RQ, interview questions (IQs) were formulated. This alignment through a cause-and-effect process contributed to the design of the probes during field entry in the research. The following research propositions have been formulated based on the findings of the literature review.

RP1.

There is a significant direct relationship between how SME entrepreneurs design and implement strategic outcomes for high growth when they perceive positive conditions in their business environment.

RP2.

There is a significant direct relationship between how entrepreneurs adapt, design, and implement strategic outcomes for high-growth sustainable performance of their SMEs when confronted with negative business results.

In response to the initial RP1, the subsequent research question was formulated (RQ1): What strategic outcomes do entrepreneurs plan for their SMEs to achieve high-growth performance? The following interview questions were devised to elicit answers that would shed light on this issue: (IQ1) In your opinion, how do you identify the strategic outcomes that will sustain the firm’s high-growth performance for as long as possible? (IQ2) In your own words, what outcomes could influence the sustainability and high-growth performance of SMEs for as long as possible? The objective of the probe was to identify deliberate strategic outcomes that would lead the firm to high-growth performance.

In response to RP2, the following research question (RQ2) was formulated, which cites: What new unplanned strategic outcomes do entrepreneurs implement when they perceive that the entrepreneurial context and business performance are unfavourable to the high growth of their SME? Consequently, the subsequent research questions were devised: (IQ3) In your own experience, what other outcomes might be relevant to achieving high-growth performance in your firm if you are not getting the results you are looking for? (IQ4) If the SME does not achieve the planned results, what are the strategic outcomes that the entrepreneur should correct? The objective of the probe was to identify emergent strategic outcomes that would facilitate the attainment of high-growth performance by the firm.

Evidently, sustainable high-growth firms contribute significantly to the economic development of entrepreneurial ecosystems, particularly in regions with a strong presence of creative and knowledge-based industries. As demonstrated in extant literature, the entrepreneurial ecosystem exerts a significant influence on the momentum towards high growth during the sustainability of the SME. The following research proposition, RP3, was therefore formulated to identify which factors facilitate this process:

RP3.

The entrepreneurial ecosystem can moderate the relationship between the strategic outcomes of SMEs and their high-growth performance when opportunities for this explosive achievement have been identified.

In addressing RP3, the following research question was posed: (RQ3) Which factors in the entrepreneurial ecosystem could influence the design and implementation of the firm’s outcomes to achieve high-growth performance? Consequently, the following two interview questions were presented: (IQ5) In your view, what factors in the entrepreneurship ecosystem are critical to achieving high-growth firms? Secondly, (IQ6) which factors in the entrepreneurial ecosystem might limit high-growth firms? The objective of this study was to identify the external factors of the entrepreneurship ecosystem that positively or negatively influence the process of high growth of the firm.

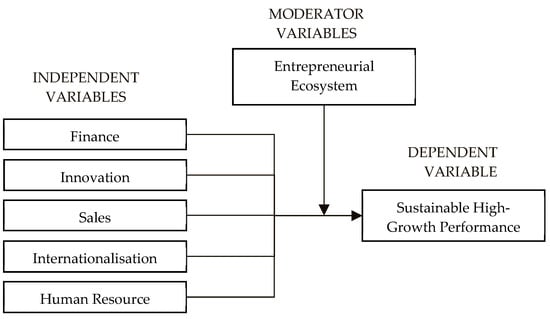

The independent variables in the study were designed to promote these goals, and the study’s model posits that deliberate goals are explicitly delineated prior to implementation, while emergent goals are formulated during the process to align with the firm’s vision [118]. The outcomes are grouped by the following categories: finance, innovation, sales, internationalisation, and human resources. The entrepreneurial ecosystem is identified as a moderator that influences firm outcomes, and the high growth of the firm is measured by consecutive years of significant outcomes. As demonstrated in Figure 2, the five dimensions of the business model are intended to guide high-growth enterprises.

Figure 2.

The conceptual model was designed to guide the study, with the objective of constructing the research propositions and questions through independent, dependent, and moderator variables.

3.3. Regulation and Sample for Conducting Multiple Case Studies

A total of 15 SMEs operating in the IT sector were selected from an initial cohort of 40 firms. The firms under consideration were required to meet the following criteria: they had to have been established for a minimum of 42 months [119], the firm in question had to have employed a minimum of ten people [7,10,90] and they had to have experienced at least 20% compound annual growth in sales for a minimum of three consecutive years [2,5,6,8]. The selection of cases was based on a comprehensive review of the databases maintained by the Association of Entrepreneurs in Chile, the American Chamber of Commerce, the Chilean–Mexican Integration Chamber, and the Global Entrepreneurial Monitor. At the inception of the research, the sample had been in existence for 6.3 years, with an average of 17 employees and an average annual revenue of USD 1,323,579. The mean annual growth rate in sales was 73.3%, with an average of 3.9 consecutive years of high growth and an average annual increase in employees of 37% since the firm’s establishment. The entrepreneurs had a range of previous experience, from zero to two ventures. It is noteworthy that eight of the founders held a master’s degree, and all of them initiated their business ventures with personal savings, and only three of them received supplementary support from public funds.

4. Prepare, Collect, and Analyse

The present section is divided into four phases. The preliminary phase entailed the conceptualisation of data collection instruments to ensure the effective execution of 15 cases during the secondary stage. Subsequent to this, a data analysis was conducted, supported by multiple sources of evidence, to construct categories and concepts through open coding review. It is asserted that the protection of information confidentiality was maintained throughout the case analysis. The data were systematically recorded and analysed using NVivo 12 software.

4.1. Crafting Instruments for Data Collection Protocols with Multiple Sources of Evidence

As outlined by [21], five sources of evidence were utilised for the purpose of data collection. The sources utilised for this study encompass documentation, archival records, interviews, direct observation, and physical artefacts. The initial source material was obtained through a documentary analysis (DA) of annual reports and accounts in various formats, including Acrobat Reader, PowerPoint, and Word. The principal components of the aforementioned reports and accounts comprised annual financial information, business plans, service catalogues, organisational structures, and other types of printed or digital documentation. The second source of evidence analysed was archival public records (APRs) from 2012 to 2019. A comprehensive examination of corporate material was conducted, encompassing informational and promotional videos, advertisements, news, social media, and other digital sources obtained from firm websites on Facebook, LinkedIn, and YouTube. In addition, a meticulous analysis of news stories in digital media was undertaken to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. The study confirmed that all the firms have a website, thus corroborating the prevailing assumption that the internet has become an integral component of modern business. The third source of evidence comprised interviews (I) with SME founders conducted between 13 December 2017 and 13 September 2018. Each meeting was conducted in Spanish at the firm’s premises and lasted approximately 1 h. The semi-structured, open-ended nature of the interview questions was intended to address the research questions and research propositions. The entrepreneurs were informed about confidentiality and that the interview could be terminated at any time. Prior to the commencement of the interview, the entrepreneurs were furnished with a detailed description of the process, which had previously been transmitted to them via email to schedule and confirm the appointment. The responses were digitally recorded with the interviewee’s permission, and written notes were taken for transcription and coding in NVivo 12. The fourth source of evidence was direct observation (DO) during visits to the firm’s premises, using [120] four-step method to ensure the success of the visits. The preliminary phase of the study involved the observation of the firm’s environment, with a particular emphasis on the following: (1) equipment, (2) staff culture, and (3) the maintenance of orderliness. The subsequent step focused on understanding the management style and values. The third step entailed normative reasoning, which facilitated an understanding of the interaction and teamwork style of the members of the firm, thereby gaining insight into the decision-making process. The final step in the process entailed an external media performance assessment. The culmination of this process was the identification of four firms, one of which was awarded the 2018 Chilean National Innovation Award from the President of Chile. The fifth source of evidence comprised physical artefacts (PAs) in the form of printed brochures and commercial documents.

4.2. Conducting Pilot

In the pilot case study, two companies were approached to test the evidence collection instruments, conduct the remaining cases correctly, and produce the appropriate report findings using multiple sources of evidence. The entrepreneurs were recruited via email, with an official letter elucidating the purpose of the interview and requesting their participation in the study. Scheduled interviews, each of which lasted for a duration of 60 min, were to be conducted at the individual’s place of work. It is important to note that each interview was digitally recorded, professionally transcribed and analysed, and responses were coded with NVivo to identify patterns of high growth. In addition to this, handwritten notes were used as a primary method of data collection. The interviews were subjected to rigorous analysis to identify the most appropriate codes for each segment. This process resulted in the identification of more than 100 codable moments or quotations within the interviews. The results of the pilot project validated the theoretical concepts identified in the literature review, confirming that the planned interview questions would lead to strategic outcomes for high growth.

4.3. Conducting the Multiple Case Studies

During the study, a total of 15 firms were visited over a period of nine months. It is an established fact that SMEs operate across a range of sectors. In order to facilitate analysis, the firms were categorised according to the sector in which they primarily generate revenue. The categorisation of the firms revealed that seven firms specialised in software design, seven offered consultancy services, and one focused on communications equipment sales. Prior to the initiation of the study, the entrepreneurs were contacted via e-mail to provide a comprehensive explanation of the study’s objective. The founder granted permission for the interviews to be digitally recorded and analysed multiple times to identify critical findings. The relevant information for each enterprise is given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Information on selected cases.

4.4. Triangulation Analysis of the Data Using the Five Sources of Evidence

The identification of findings is a pivotal component of the multiple case study, for which [21] proposed the utilisation of triangulation as a methodology to validate findings through the application of diverse evidence. The evidence presented in this study encompasses a variety of sources, including documentation, archival records, interviews, direct observation, and physical artefacts. Triangulation is imperative for the execution of rigorous research [121], and it is critical to the collection of accurate information [122]. Research methodologies are subject to limitations; therefore, ancillary techniques should be employed to reduce bias. A three-stage procedure was implemented with the purpose of reducing potential interference. This process entailed the sequential arrangement of the data according to the order in which visits to the firms were made, whilst simultaneously ensuring that no two or more cases were analysed in parallel. Following the compilation of all the data, a review of each of the 15 cases was conducted. Redundancies were subsequently eliminated.

It is vital for SME entrepreneurs to identify strategic outcomes with which to measure the high-growth performance of their firm. Therefore, the RQ1: “What strategic outcomes do entrepreneurs plan for their SME to achieve high-growth performance?” was posed, and according to the entrepreneurs, positive profit outcomes are important for the growth of the firm. The following quotations represent the most significant findings in support of this outcome. As demonstrated by the Case M example, some of the most salient narratives emphasise that an SME with one of the highest profit percentages in the multiple case studies reported: “The firm is currently pursuing an increased revenue strategy, with the objective of increasing sales from $8 per sale to $300 per sale”. This underscores the necessity for higher profits as SMEs expand. If a firm is currently selling automotive reports at an average value of USD 8, it should soon be offering more comprehensive reports at a significantly higher price. It is acknowledged that a project of merit necessitates a timeframe of three to four years to reach its full potential, at which point it can commence operations with a viable profit margin. This is a scenario with which entrepreneurs seeking high profits are always confronted. Sustained positive profits require an understanding of how the services offered to customers are profitable, as illustrated by Case C, which refers to finding a product that is a “lifeline to run the business every month and be able to invest from it”. It is imperative to acknowledge the context in which a business operates, as this exerts a substantial influence on its financial outcomes. This finding was corroborated by various sources of evidence, highlighting adjectives such as high margin to secure money, not tying up resources, new ventures to increase profits, and high profits through sales, among other quotes.

For entrepreneurs, the generation of rapid sales is of paramount importance in order to sustain investments and support high growth. A dearth of liquidity can result in the collapse of a commercial enterprise. Entrepreneurs indicated that the importance of swift sales outcomes was a key finding. The quotations that follow are the most representative of the key role that sales play in the context of high-growth firms. Case M, responsible for the launch of a prominent entrepreneurial initiative in Chile, emphasised the importance of prioritising short-term sales: “My primary objective is to maximise sales and enhance profitability, thereby creating the possibility for the expansion of profitable ventures”. Case O emphasised that, in a “high-growth product industry, a 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 3 scaling cycle is to be expected”. Case N, a prominent Chilean innovator, acknowledges the pivotal function of sales, stating, “We are experiencing annual growth that is double the rate. It is anticipated that, this year, there will be an increase of 100% in sales, representing a second consecutive year of growth”. The subsequent quotations demonstrate the significance of short-term sales in facilitating organisational expansion. The analysis highlights elements such as the generation of rapid sales, large contracts, steady growth in sales, explosive growth, rapid scaling of sales, and doubling of sales over the previous year, among others.

The RQ2 sought to identify novel unplanned strategic outcomes implemented by entrepreneurs when confronted with an unfavourable business context and suboptimal firm performance, particularly with regard to the growth of their SMEs. The identification of emergent outcomes constituted the underlying objective of this inquiry. Geographical expansion emerged as a pivotal outcome for achieving high growth. Entrepreneurs identified expansion into foreign markets as being of paramount importance for achieving high growth. In the case of A, a seasoned entrepreneur with extensive international experience, there was concurrence with the following statement: “Our client base extends to Argentina, Peru, and Colombia. However, emphasis was placed on the fact that sales are a prerequisite for any further expansion, and that expansion can generate sales, but that internationalisation and sales must be pursued together”. Notwithstanding the general consensus regarding the significance of geographical expansion, a paucity of entrepreneurs possesses experience in the field of international sales. Case K also concurred, stating: “Merely providing a satisfactory product or service is insufficient. The transient nature of global markets renders international relationships of paramount importance. The firm’s personal relationships proved instrumental in facilitating its relocation from Chile to Colombia, where it experienced significant growth. This approach was subsequently employed to expand into Peru, Colombia, and Mexico. These opportunities enabled the firm to enter new markets”. In the context of Chilean entrepreneurship, geographical expansion is of particular significance given the country’s modest size and population of approximately 18 million. Conversely, the founders of the six SMEs highlighted the challenge of formulating a “geographical growth plan that extends over years” due to their limited scale. The duration of the data analysis process was approximately 18 months, and no subsequent interviews were conducted via telephone or email. During the investigation, no evidence was found that there was a direct relationship or interaction between the 15 SMEs that could generate biases during the multiple case studies. Due to the meticulous review process applied to each transcript, a maximum of one source of evidence was coded per day, and no concurrent analysis was undertaken.

The second emergent outcome is innovation, which, according to Case A, “necessitates the creation of a product that is challenging to replicate and distinguishes the producer, even in circumstances where there are five individuals engaged in the sale of ice cream in a given locality. The pertinent question, therefore, is how to market the most superlative ice cream”. In the case of M, the meaning of innovation lies in the fact that “we created a new product that today already represents 20% of the firm’s sales. In other words, we have created new products, and we have grown our own products here”. Case N similarly determined that “innovation is the result of its new banking application, the first of its kind for secure banking transactions”. Case O seeks to achieve “scalability of its products through artificial intelligence and automation as a fundamental outcome”. As illustrated in Table 5, the most representative quotes for each case are presented, alongside the sources of evidence that were used.

Table 5.

Triangulation summary for multiple sources of evidence.

It is evident that external factors engender opportunities or threats in the entrepreneurial ecosystem of the firm. Therefore, RQ3 was formulated with the objective of identifying variables that are external to the entrepreneur but influence high growth and are part of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Entrepreneurs are acutely aware of the importance of a supportive ecosystem for their entrepreneurship, as Case K remarks at the inception of his firm: “A very interesting community of entrepreneurs was formed through different initiatives, some public, some private”. In this sense, Case L observes that “there is a very interesting entrepreneurial force, especially in the world of younger professionals”. Case N, winner of the Innovation Prize in Chile, provides further elaboration on the role of the press as a “pivotal component of the ecosystem”. He emphasises that “positive media attention can facilitate the dissemination of innovative ideas at minimal cost”. Furthermore, he states that the “environment for entrepreneurship is favourable, with external factors such as the state and the new wave of fintech entrepreneurship providing support”. A plethora of factors were cited by the various cases, including, but not limited to, “economic stagnation” (case A); “change of government” (cases B and E); “government has short-term vision” (case F); “business intervention” (case G); “no regulations to stimulate entrepreneurship” (case L); “economic fluctuations in the country” (case C); and “variation in reforms” (case D).

4.5. Open Coding to Build Categories and Concepts

During the interview with the firm’s founder, four open-ended questions were posed with the aim of identifying the critical outcomes required to achieve high growth. As posited by [123], the utilisation of qualitative codes assumes significant importance as these codes embody the fundamental essence of the research narrative. When categorised according to their affinity and regularity as a pattern, these codes facilitate the design of categories and their respective connections. The selection of the most suitable open-source code was the result of a rigorous process involving multiple reviews of the evidence. This process identified 79 codes, which were then grouped by affinity into 19 sub-categories in order to align the findings with the theory. In the subsequent phase of the research, the ten categories were organised into five central themes. These themes were then used to identify four strategic outcomes: positive profits, rapid sales, geographical expansion, innovation, and the impact of the entrepreneurial ecosystem on the moderation of the design and adaptation of the outcomes. However, following the identification of the relevant codes, these were grouped into subcategories. These subcategories are codes of a higher level, since the language used in the signatures may be different. Therefore, the affinity allows confirmation that at least 10 out of 15 cases refer to a challenge or situation assigned to a code. [124] acknowledged the inherent limitations of all research methods and posited that the employment of a range of methodologies can mitigate the bias associated with a single approach. In order to address this issue, a three-step procedure was developed to circumvent potential interference during the coding stage. The initial step entailed coding each case. To mitigate noise, simultaneous coding of two or more cases was eschewed to achieve a more refined analysis. The second stage of the procedure entailed a comprehensive review of all qualitative data collected and documented in NVivo. The third and final stage of the procedure was designed to avoid the repetition of codes as possible synonyms or with the same meaning. In this study, positive profit is defined as a situation where a firm’s total income exceeds its total expenses, resulting in a net profit. This is achieved through strategies to avoid a lack of financial liquidity, financing plan, financial optimisation, and management control. This key performance outcome is utilised to evaluate the efficacy of the firm’s sales of services or goods, subsequent to the settlement of production costs. The attainment of a sustainable equilibrium between sales and costs, exceeding the industry average, is indicative of a successful outcome. A codable moment was identified in the firm case, which reported that profits are important for sustaining high growth in SMEs. The term rapid sales refers to a situation in which a firm experiences a fast or accelerated rate of sales of its products or services in a relatively short period of time through the implementation of efficient business solutions, high levels of customer experience, marketing strategy, and sales roadmap. This is the primary outcome measure for evaluating the impact of positive initiatives aimed at promoting rapid, high-growth entrepreneurship. It is characterised by the attainment of high sales in a brief period, which are subsequently sustained over an extended timeframe. A codable moment was recognised when the founder quoted that sales are a key outcome of high growth when they are generated very rapidly over a long period of time. Geographical expansion is defined as the sale of products produced in the home country to international markets, with or without the establishment of a physical presence, through favourable domestic trade, positive international competitiveness, and international diversification. It supports the entrepreneurial endeavour to expand the business to other regions to sell or import goods and services. This is achieved by generating high sales in a short period of time, which are then sustainable over the long term. A codable moment was assigned when the entrepreneur mentioned that they have customers in other countries, and that global expansion and internationalisation of the firm are essential for achieving high growth. Innovation is defined as the provision of unique solutions to problems through the creation of unique products or services that enable the high growth of the firm. The entrepreneur’s reference to new product and service differentiation and upgrading, with the objective of enhancing competitiveness and ensuring high-growth performance, constituted a codable moment. The entrepreneurial ecosystem is defined as a system that fosters an environment wherein entrepreneurs are able to comprehend the intricacies of adverse public policies and business contexts and respond positively to favourable business environments. The number assigned in each case identifies the open code that was discovered during the data analysis. Table 6 presents the codes identified and the strategic outcomes that emerged from the multiple case studies.

Table 6.

Open codes, subcategories, categories to build themes for high growth.

In qualitative research, the utilisation of codes is not ordinarily associated with frequencies or statistics, as the emphasis is directed towards the in-depth comprehension of experiences and their underlying meanings. This approach is adopted in preference to the quantification of occurrences, which is characteristic of quantitative research methodologies. Qualitative research explores the underlying causes and mechanisms of phenomena, relying on rich descriptions and interpretations rather than numerical counts. Whilst it is true that certain forms of qualitative analysis may entail the counting of items, the fundamental objective of such analysis is to identify themes, patterns, and relationships within the data. The purpose is not to ascertain the frequency of specific codes or themes [125,126].

5. Conclude and Validate

Ref. [127] observed that there is a paucity of systematic research on the most exceptional firms, which achieve atypical results due to their level of performance through an outlier outcome that can be exceptionally good or exceptionally bad compared to their economic group. Consequently, the validation of findings is imperative. Ref. [128] asserted that findings are evaluated through theoretical triangulation, while [21] emphasised the necessity of external confirmation to validate findings, demonstrating the potential for generalisation of evidence from multiple case studies.

5.1. Validating the Research Propositions: Enfolding the Literature (External Triangulation)

The present study validates the empirical findings by employing an external triangulation of the research, thereby validating the probes identified for RP1. This empirical assumption is based on the premise that entrepreneurs meticulously formulate business models with the deliberate intention of achieving high-growth outcomes, thereby facilitating positive profit margins through rapid sales. This approach is purported to ensure the strategic, sustainable, and competitive performance of the firm.

The positive profits reported by all firms represent a significant outcome for the assessment of the high-growth performance of their SMEs. As asserted by [5], profitability is delineated as the average annual revenue growth of 20% or more over a period of three consecutive years characterised by high growth. As [46] asserted that the firm’s profits are expected to be sustained over a period of six years, thereby facilitating organisational growth through a minimum 20% increase in revenue. Ref. [8] further emphasised the necessity of multiple outcomes for comprehensive measurement of high-growth performance, including profit. In a similar vein, Ref. [15] posited that profits function primarily as an individual outcome, serving to support entrepreneurs during the high-growth process. A fundamental concern for the [2] is to comprehend how to account for SMEs that achieve elevated resource efficiency and productivity gains with stable sales, where enhanced profitability is a salient outcome. However, Ref. [129] emphasised that sustainable growth requires firms to take responsibility for environmental protection activities with green energy and climate change mitigation, accompanied by rapid economic growth where profits play a relevant role in balancing business and environmental outcomes. According to [130], attaining optimal profits necessitates the adept management of total assets, thereby invoking a response from the market. As [131] asserted, profitable firms are more likely to attain a state of sustainable growth that integrates high profitability with enhanced alignment with both business and policy objectives. In the same context, ref. [132] stated that the pursuit of profit can put a strain on positive cash flow, which can have an impact on SMEs as they typically run businesses with a very limited financial budget. The British Business Bank’s Enterprise Research Centre [133] identifies productivity as the contemporary business challenge, and the attainment of growth is contingent upon this in order to achieve positive profits.

Rapid sales are a strategic outcome deliberately reported by firms during their high-growth period. According to the research of [7], such firms are responsible for a significant proportion of the productivity growth at industry level, but only during the high-growth phase. This outcome is five times more significant than the employment-based one. In addition, ref. [134] discovered that there are positive interactions between return on assets (ROA) and sales growth. Furthermore, he found that firms experiencing rapid sales growth accompanied by an increase in profitability or productivity are less likely to suffer from a potential performance setback. In a similar context, ref. [8] corroborated the finding that firms that endure high-growth cycles tend to exhibit sustained growth, attributable to absolute increases in sales and profits. However, upon exiting the market, these firms encounter a decline in overall growth. Ref. [135] defined a high-impact firm as one that has at least doubled its sales over the four-year period and has experienced employment growth of two or more over the same period. However, ref. [136] reported that the presence of high-growth firms in the downstream industries is associated with a higher increase in sales, but not with an additional increase in employment, which represents a stimulus to their productivity growth. Correspondingly, ref. [137] discovered that the most lucrative high-growth firms tend to exhibit increased productivity, greater internationalisation, and innovation, yet are smaller in size and earlier in their corporate life cycle. Nevertheless, as demonstrated by [138], sales are subject to temporal fluctuations, with the probability of substandard performance increasing in the absence of a firm’s commitment to innovation endeavours.

The alignment of theory and empirical findings validates the RP2 probe and its application in entrepreneurial contexts. Specifically, the validation is evidenced when entrepreneurs adjust their strategic outcomes in response to the perceived necessity of additional outcomes for pursuing high-growth objectives. It can be concluded that geographical expansion has become a newly emergent third outcome in the research list. Ref. [15] regarded this as a relevant initiative for export, with the prediction that it will be particularly successful in domestic economies in emerging markets. However, they also state that it “cannot support a large number of high-growth firms serving only the local market”. Ref. [139] posited that the geographical scope of SMEs exerts a positive influence on the growth rate of firms, a phenomenon that is highly context dependent. This finding emerges when managing the complex operational governance through the international competencies of entrepreneurs, which may encompass international education and experience, while concurrently constraining expansion to the entrepreneur’s home region. In a similar vein, ref. [140] found that the business models of high-growth firms evolve over time to become high-growth across large regions to attract venture capital investment. This highlights the importance of generating new strategic outcomes, which requires a dynamic capability involving “routines and processes of expansion, replication, and synchronisation” as recognised by [6]. Ref. [141] posited that enterprises pursuing geographical expansion must demonstrate enhanced responsiveness to consumer expectations and incorporate market intelligence into their business models. As [142] also observed, internationalisation strategies have been demonstrated to contribute to the growth of resilient firms through the mechanisms of digitalisation and trust building. [143] argued that high-growth exporting (HGX) firms are dynamic and active in international trade to achieve high performance outcomes through sophisticated products, high prices, and extensive diversification. In contrast, [101] hypothesised that a favourable interplay exists between innovation and export activity, culminating in substantial cash flow and liquidity outcomes for SME growth. In conclusion, it can be summarised that top-performing firms possess the expertise to compete in the international arena, as asserted by [144]. This assertion underscores the imperative of internationalisation initiatives for the high-growth trajectory of firms. In accordance with the findings of [145], the acceleration of “global value chains (GVCs)” presents novel opportunities for SMEs to engage with global markets.

Innovation is a strategic outcome for the business models of SMEs pursuing sustainability. Ref. [146] concluded that innovation in the supply chain is an indicator of competitiveness. Moreover, ref. [147] have determined that supply chain collaboration with customers and suppliers, both domestic and international, as well as local universities and international competitors, facilitates innovation in SMEs. In a concurrent study, ref. [148] identified innovation speed as a pivotal component of operational performance, which has been demonstrated to enhance quality and foster competitive advantage. This innovation has the potential to yield substantial growth outcomes. In this regard, ref. [149] posited that the generation of value in digitisation-based business models is a pivotal consequence of innovation, a notion corroborated by [150], who affirm that digital transformation exerts a favourable influence on firm performance, manifesting in three distinct outputs: radical innovation, technological innovation, and non-technological innovation. Ref. [151] posited that the following outcomes are of significance and novelty for the business model: the introduction of new products and services as a new offer; the commencement of work with new business partners; the sharing of new responsibilities with business partners; the focus on a completely new market; the creation of new ways to generate revenue; and the introduction of a new pricing system. The significance of robust strategies in propelling innovation outcomes is emphasised by [152], who substantiate that optimal SME performance is contingent on creativity and open innovation as strategies. In this regard, ref. [153] stated that there is a lack of understanding of how team members collaborate and the role they play in transforming digital technologies into innovative outcomes for their firm. Conversely, ref. [86] posited that enhanced product performance will yield superior outcomes, or, in accordance with [154], SMEs that prioritise digitalisation and environmental sustainability competencies can optimise resource allocation and ensure effective commitment to innovation outcomes.

The entrepreneurial ecosystem has been identified as a moderator in achieving firm outcomes during periods of high growth. In their seminal work, ref. [155] posited that a combination of regulatory institutions is necessary to achieve high-growth outcomes, as opposed to relying on a single institution. This combination comprises investor sanctuaries, the purpose of which is to protect investors; labour-oriented economic hubs, the function of which is to tightly regulate market labour; and creditor-oriented economic frontiers, the role of which is to protect the entrepreneur. Ref. [156] further emphasised the pivotal role of business ecosystems centred on knowledge diffusion and regional absorptive capacity, in conjunction with other crucial regional variables, for high-growth firms. The aforementioned factors comprise entrepreneurial culture, professional talent, intermediary services, networks, financing mechanisms, and demand growth. Ref. [157] defined the entrepreneurship ecosystem as all the interdependent agents and factors that enable and constrain entrepreneurship in each area to achieve firm productivity through networks, culture, and formal institutions, moderated by leadership, talent, knowledge, intermediaries, finance, demand, and infrastructure. In a concurring perspective, ref. [158] posited that entrepreneurial activity is regarded as a vital catalyst for regional economic growth. It is contended by the aforementioned sources that the influence of disparate entrepreneurial endeavours on regional economic development is tempered by entrepreneurial ecosystems that embody diverse business configurations. In accordance with the aforementioned points, ref. [159] determined that the entrepreneurial ecosystem within the digital sector is of consequence for the process of “opportunity scanning” and the selection of potential investment avenues. The development of an economic region is contingent on the presence of conducive entrepreneurial ecosystems that foster the establishment of ventures in novel sectors. Consequently, ref. [160] asserted that the engagement and commitment of an entrepreneurial ecosystem are predicated on both opportunity and urgency. However, ref. [114] identified several uncertain patterns in the ecosystems of entrepreneurship in different countries, such as the potential positive and negative effects of government intervention with its policies and programmes, the configuration of informal and formal relationships within financial systems, and the social legitimisation of diversity in entrepreneurship.

5.2. Modifying the Theory: Logic Model

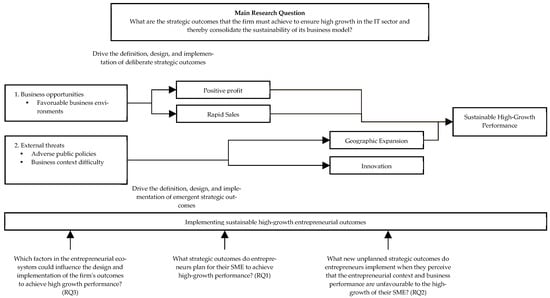

The multiple case study methodology culminates in a conceptual proposal using [21] logic model to identify cause–effect relationships in this complex phenomenon of identifying strategic outcomes for high growth. The initial step involves establishing a connection between the research objective, which is to ascertain the methods employed by IT entrepreneurs in developing strategic performance outcomes that ensure the sustainability of the high-growth business model. In a subsequent step, elements were identified from RQ1, RQ2, and RQ3 that would assist in answering the central objective of the research and that would adequately guide the results of the strategic outcome plan for high-growth SMEs. The logic model is also a visual map that can be used to infer patterns about the phenomenon under study [36]. This analytical technique, as proposed by [21], involves the empirical matching of events to predict an effect and can be employed in conjunction with the pattern matching technique. In this multiple case study, the logical model commences with an understanding of the intended and emergent strategic outcomes for high firm growth, which necessitates a set of factors inserted into the entrepreneurship ecosystem. The arrows thus represent the cause-effect sequence from the process of detecting business opportunities and external factors influencing the definition, design and implementation of deliberate and emergent outcomes for Sustainable High-Growth Performance. As illustrated in Figure 3, the logic model provides a visual representation of the sequence of events that influence SME creation.

Figure 3.

The logic model has been designed to facilitate comprehension of the impact of business opportunities and external threats on the construction of deliberate and emergent outcomes. These outcomes are driven by research questions that emerge during the case analysis.

6. Research Findings

In favourable circumstances, strategic planning for high-growth enterprises has been shown to yield positive profits and rapid sales as a result. However, there is a gap in the extant literature concerning the manner in which entrepreneurs, when perceiving threats to their SMEs and potential negative performance outcomes, develop emergent outcomes with a view to sustaining explosive growth through geographical expansion and innovation. The mean annual increase in sales for the sample was 61.8% for three consecutive years and 73.3% for four consecutive years. Furthermore, an average of 3.9 years of high-growth period was identified for the firms analysed, of which 80% had four consecutive years of high growth. Furthermore, nine out of fifteen firms reported geographic expansion into at least one country in the region. Colombia was the economy cited by seven SMEs for their exports, followed by Peru with five mentions and Mexico with four.

The present study corroborates the hypothesis that empirical findings pertaining to SMEs in emerging economies are inconclusive. However, recent research has identified new paradigms in the measurement of firm establishment prior to high growth. The mean establishment period was 25 months in this study, contrasting with the 42 months reported by the [161]. At the time of the study, the average age of the firms was 6.3 years, with an average annual sales figure of 56.1% since their foundation. This enables the empirical validation of the claim that they are above 20% in terms of average annual sales, as indicated by major reference sources such as the [10]. IT firms require a focus on key performance indicators (KPIs) that prioritise rapid sales, positive profit, geographic expansion, and innovation. In addition to these metrics, it is imperative to cultivate other financial outcomes, such as cash flow, customer acquisition, revenue per hour, average revenue per customer, new services per semester, and others, which are comprehensible to small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). [162] confirmed in their study, business strategies play a mediating role in innovation practices that contribute to the competitiveness of SMEs. The study further corroborates the significance of favourable business opportunities, in addition to external threats such as adverse public policies and difficulties in the business context.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

It is anticipated that SMEs operating within the IT sector will continue to exhibit growth and evolution in response to the increasing utilisation of digital systems and artificial intelligence within the global economy. This evolution is driven by the emergence of novel mechanisms for work and entrepreneurship, facilitated by the application of information and communication technologies. The context will influence the design of deliberate or emergent outcomes, with the aim of guiding the business model towards high growth for the firm. However, it is important to note that the results of this study should be interpreted with caution, as it was conducted in a highly specialised context, encompassing a single sector and a specific nation, thereby facilitating a more profound and nuanced understanding of the intricacies of this particular management phenomenon.

A critical finding of this multiple case study is the paradigm established by the [161], which qualifies established firms as such when they have been in existence for 42 months or more. However, this paradigm does not apply to the IT sector, which has already begun to deliver high-growth results at 25 months. This poses a considerable challenge for educational institutions and public policy, as well as for entrepreneurs attempting to sustain their firms over the long term and anticipate constant change in the different contexts of the global economy. This study emphasises the importance of anticipating emergent scenarios through strategic planning, with the objective of mitigating risk before the occurrence of potential threats. It is recommended that dynamic business models be developed, incorporating more strategic and formal contingency planning.

Despite the theoretical underpinnings of this study having been validated, the results offer a valuable opportunity to enhance our understanding of the significance of deliberate planning for outcomes intended to guide high-growth strategies and to consolidate firm sustainability in crisis situations through emergent outcomes. The findings emphasise the necessity of meticulously integrating four strategic outcomes to achieve substantial SME growth. However, there is a paucity of empirical evidence to elucidate the manner in which entrepreneurs formulate outcomes in different sectors of the global economy.

The extant literature employs a variety of strategic outcomes to measure high growth, yet there is a paucity of consensus on the definition of this sustainable high-growth process. Although a substantial body of literature exists that identifies the strategic outcomes of high-growth firms, the theory lacks a defined taxonomy and is inconsistent. Following a period of over four decades in which a significant volume of relevant literature has been published, and numerous definitions, criteria, and outcomes have been proposed for defining high-growth firms, these have coexisted for many years. Ref. [163] observed a favourable relationship between the perceived importance and performance of each metric designed to measure SME performance. Furthermore, ref. [164] posited that “engaging in such counterfactual thinking allows entrepreneurs to consider past failures in the process of constructing more effective strategies that generate positive outcomes in the future”. This indicates that entrepreneurs can lead to negative outcomes for their firms if they suffer a high number of failures.

It is important to note that in the selected literature sample, 69% of the studies focus on SMEs and small firms, where 39% of the cases have at least 3 consecutive years of high growth, followed by 22% for 5 years and 17% for 4 years. A majority of the extant studies on this subject have been conducted in the United States (26%), with a similar number having been carried out in the UK (26%), and a smaller number in European countries (19%). The analysis further reveals that manufacturing and services account for the highest proportion of research at 29%. This information underscores a substantial gap in the availability of research related to SMEs in the IT sector in emerging countries, indicating that studies conducted in other regions may not adequately address the needs of undeveloped economies.

8. Research Contributions

The multiple case studies yielded a number of contributions, which were grouped into three categories: theoretical, methodological, and practical. The following section provides a detailed description of these contributions. Ref. [21] observed that the contributions are unconventional and of significant universal public interest, and that “the underlying issues are of national importance, either in theoretical terms or in terms of policy or practice”.

8.1. Theoretical Contributions

The initial contribution is founded on a more profound comprehension, attributable to the restricted terminology and definitions proposed for conventional outcomes established to measure high growth. Despite the existence of numerous studies on this phenomenon, they have not been exposed to suggest new outcomes in business models, and they have experimented in the traditional areas of sales and new jobs. The second theoretical contribution is derived from the identification of the various types of defining high growth. The theory provides a range of definitions of high growth but does not yet offer a definitive measurement of high growth, nor its limits. These include rapid growth, organisational growth, gazelles, very rapid growth, scale-up, supergrowth, extraordinarily high-growth, hyper growth, strong growth, very rapid growth, significant business growth, exponential growth, and fast-growing. The third contribution is constituted by the presentation of a more comprehensive terminology and taxonomy structure of the high-growth based on the ordering of the two types of outcomes in deliberate and emergent. The final contribution is the moderator of external and dynamic factors that are not controlled. This allows us to observe the phenomenon from an ontological perspective and to consider how different perspectives influence reality. This external factor may be able to classify the effects that may positively influence or negatively limit the definition of the outcomes of high growth. This proposal is an orderly way to understand the maturity of the entrepreneur and the entrepreneurial ecosystem in terms of constructing a sustainable business model.

8.2. Methodological Contributions

The logic model’s design proposes an alternative approach to observing the effects from an outcome perspective, encompassing the definition, design, and implementation of deliberate and emergent outcomes, through the causes that are the opportunities and threats aligned to the three RQs to answer the main research question. The second methodological contribution is internal and external triangulation. As [125] asserted, this strategy serves to mitigate the risk of conclusions reflecting solely the systematic biases or limitations inherent to a particular source or method. The implementation of this multiple case study method necessitated the utilisation of both internal and external triangulation, encompassing the consideration of the five adapted sources of evidence, with the objective of validating the factors that were identified during the data analysis process. Subsequently, an analysis was conducted on external sources, including academic research and reports from non-governmental institutions. The objective of this analysis was to confirm that the findings effectively represent the factors influencing the process of scaling up SMEs. Ref. [127] asserted that data triangulation, defined as the process of combining multiple sources of information and theory to generate a comprehensive understanding of a particular phenomenon from diverse perspectives, is an integral component of the study’s evaluation process.

8.3. Empirical Contributions

It is imperative to note that both deliberate and emergent strategic outcomes are necessary for the process of high-growth firm development, in which rapid sales, positive profits, geographical expansion, and innovation are the strategic drivers. It is incumbent upon policymakers to ascertain the specific competencies and insights that are indispensable for the training of entrepreneurs, with a view to facilitating the expansion of their established firms. In this context, the empirical contribution of understanding the restrictions on this process and the key outcomes necessary to sustain firms for more than three consecutive years will also be of benefit to them.

9. Research Limitations

The continued growth and evolution of SMEs in the IT sector is predicated on the increasing utilisation of digital systems and AI within the global economy. This phenomenon is driven by novel modes of operation and entrepreneurship, enabled by Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). This will influence business model design to guide firms towards high growth. However, it is important to note that the results of this study should be interpreted with caution, as it was conducted in a highly specialised context, encompassing a single sector and a specific nation, thereby facilitating a more profound and detailed understanding of the intricacies of this particular management phenomenon.

9.1. Theoretical Limitations

The research is subject to four limitations, the details of which are provided below. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, substantial research has been conducted that facilitates a more profound understanding of the phenomenon of high growth. The initial constraint pertained to the absence of consensus. Although literature on this subject has been present since 1978, there is a divergence of opinions regarding the quantification of performance and the factors that influence the high growth of SMEs. In the field of research in Latin America and emerging countries, there is a paucity of studies. This situation presents a valuable opportunity for other researchers to undertake a more detailed and rigorous examination of the results reported here, thereby contributing to the advancement of the field.

9.2. Methodological Limitations

The first limitation was the selection of firms with an estimated annual revenue growth rate of more than 25% during three consecutive years. The application of these criteria was instrumental in mitigating the potential for variability and ensuring the uniformity of the sample. This was imperative to avert the possibility of outcomes that might have been characterised by inconsistencies in the dependent variable, which could have manifested as periods of minimal or no growth during specific phases of high-growth periods. The defining characteristics of the sample in this particular research endeavour constitute a limitation, should the objective be to identify and validate the potential causes of the associated correlations. Such a feat is not feasible in the context of this qualitative analysis.

The study of each of the 15 SMEs was conducted at one point in 2017–2020, without taking into account changes over time in the external factors that constitute the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Chile. Despite the endeavour to comprehend the matter of environmental change, this second limitation precluded the assessment of these adjustments over time, which have the capacity to positively or negatively influence the strategies corresponding to the evolution of each of the moderator variables. In order to achieve this objective, it is necessary to conduct a longitudinal analysis. This will involve the collection and analysis of data on the same sample at multiple points in time. This is a step that was not included in the present research.