Digital Business Model Innovation in Complex Environments: A Knowledge System Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Methodology

3.1. Selecting Databases and Keywords

3.2. Selecting the Relevant Articles

4. Thematic Analysis

4.1. Traditional Perspectives on Business Model Innovation

4.1.1. Activity System Perspective

4.1.2. Resource-Based View

4.1.3. Strategy Perspective

4.1.4. Ecosystem Perspective

4.1.5. Cognitive Perspective

4.1.6. Dynamic Capabilities Perspective

4.1.7. Institutional Perspective

4.1.8. Organizational Learning Perspective

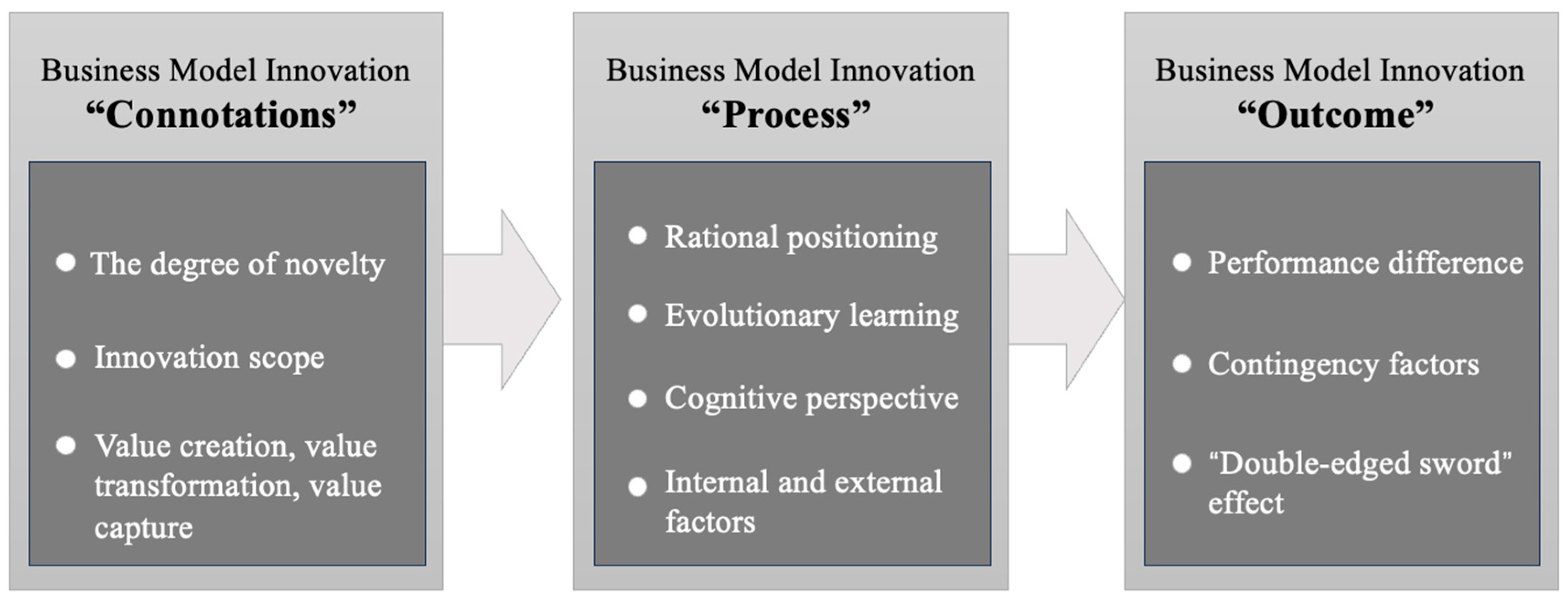

4.2. Three Core Issues of Business Model Innovation

4.2.1. The Multiple Connotations of Business Model Innovation

4.2.2. Business Model Innovation as a Process

- (1)

- Stages and Process of Business Model Innovation

- (2)

- Internal and External Factors Influencing Business Model Innovation

- (3)

- The Role of Experimentation and Learning in Business Model Innovation

4.2.3. Business Model Innovation as an “Outcome”

- (1)

- A New Source of Performance Difference

- (2)

- Exploration of Contingency or Moderating Variables

- (3)

- Limited Attention on Negative Effects

4.3. The Rise of Digital Business Model Innovation

4.3.1. “New Connotations” of Digital Business Model Innovation

4.3.2. “New Characteristics” of the Digital Business Model Innovation Process

4.3.3. “New Dilemma” of Enhancing Performance Through DBMI

4.4. Rediscovering Digital Business Model Innovation: The Emergence of the Knowledge System Perspective

4.4.1. The Emergence of the Knowledge System Perspective in Digital Business Model Innovation

| Research Perspective | Activity System Perspective | Knowledge System Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Connotation | The activity system perspective conceptualizes business models as “a set of interdependent activities or actions centered around a focal firm, involving the focal firm itself, its partners, suppliers, or customers” [11]. | The knowledge system perspective conceptualizes the business model as a structured knowledge cluster, defined as “cognitive or mental representations regarding how the firm sets boundaries, creates value, and organizes its internal governance structure” [26]. |

| Research focus | This perspective focuses on the behavioral activities related to BMI—particularly, how companies create value through transactions and key activities within their business models. | The knowledge system perspective focuses on how firms coordinate business-related components (such as factors, resources, and conditions) to form knowledge themes (or knowledge subsets), and how they further coordinate these knowledge themes to create and deliver value. |

| Key innovation elements | The activity system perspective identifies critical activities such as training, development, manufacturing, budgeting, planning, sales, and service, which significantly influence the effectiveness of BMI [23]. | The knowledge system perspective pays attention to the creative combination and utilization processes of component elements during BMI, emphasizing the specific experimental and learning mechanisms involved. |

| The main differences | The activity system perspective emphasizes how these activities, their interdependencies, and cross-boundary interactions collectively enable value creation. | The knowledge system perspective focuses on how knowledge facilitates mechanism creation, highlighting that BMI encompasses not only explicit knowledge components like value propositions and process architectures, but also implicit knowledge components such as skills, schemas, and sense-making. |

| Representative studies | Zott and Amit, 2010 [11]; Snihur et al., 2021 [13]; Tykkyläinen and Ritala, 2021 [121]. | Chen et al., 2021 [27]; Sosna et al., 2010 [44]. |

4.4.2. Applicability of the Knowledge System Perspective in the Digital Context

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Findings

5.2. Implications for Policy and Practice

5.3. Future Agenda

- Developing an integrated analytical framework: Despite increasing scholarly attention, current research on DBMI remains fragmented and lacks a shared conceptual foundation. Future studies should aim to build an integrated analytical framework that clearly defines key constructs, explicates their interrelations, and outlines the boundaries of DBMI. A unified framework should incorporate both structural and processual elements, reflecting the interplay between digital capabilities, organizational learning, and strategic adaptation;

- Unpacking BMI mechanisms in the digital context: The role of DTs in shaping BMI processes remains underexplored. Existing research often treats tools as static enablers, neglecting the dynamic, iterative processes through which they interact with organizational routines and innovation behaviors. Future studies should examine how DTs co-evolve with experimentation, organizational learning, and systemic adaptation. Multi-level and longitudinal research designs are especially valuable for capturing these interactions over time. Emerging scholarship also suggests the importance of behavioral and team-level dynamics, such as creativity and sustainability orientation, which mediate the relationship between digital affordances and innovation outcomes under uncertain conditions [125]. These insights point to the need for integrating cognitive, social, and technological dimensions into the study of DBMI;

- Developing the knowledge system perspective in complex environments: The KSP offers a promising lens through which to understand DBMI in the context of increasing complexity and dynamic environments. By conceptualizing business models as structured, interdependent knowledge architectures, the KSP emphasizes how knowledge—both human and artificial—is generated, recombined, and applied in innovation processes. This approach captures emerging phenomena such as human–machine collaboration, algorithmic coordination, and distributed learning within digital ecosystems [126,127]. As DBMI becomes more integrated into digital infrastructures, innovation processes are no longer solely driven by humans, but arise from the interplay of distributed knowledge units, both human and artificial, operating within complex digital ecosystems. In this context, the transition from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0 highlights the integration of human creativity into AI-enabled systems. Future research should explore how collaborative intelligence and distributed cognition drive business model transformation. Recent research highlights that artificial intelligence greatly improves organizational knowledge processing, especially in the externalization and combination stages, but struggles to replicate the tacit, context-sensitive judgment unique to human cognition [128]. This reinforces the relevance of Nonaka’s SECI model, which emphasizes the dynamic interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge [129]. Future research should examine how AI-based systems and human decision-making jointly shape BMI, and how firms orchestrate human–AI collaboration to co-create adaptive, value-generating business models. This approach extends the KSP by including artificial knowledge agents (e.g., AI systems and algorithmic processes) as active participants in digital business model transformation. This is particularly relevant in the emerging era of human–AI collaboration, where innovation is increasingly shaped by distributed, heterogeneous knowledge sources.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coreynen, W.; Matthyssens, P.; Van Bockhaven, W. Boosting servitization through digitization: Pathways and dynamic resource configurations for manufacturers. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 60, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Parida, V.; Oghazi, P.; Gebauer, H.; Baines, T.S. Digital servitization business models in ecosystems: A theory of the firm. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, P.J.; Heaton, S.; Teece, D. Innovation, dynamic capabilities, and leadership. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 61, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.S.; Wäger, M. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R.; Clark, C.E.; Malcolm, D.G.; Craft, C.J.; Ricciardi, F.M. On the construction of a multi-stage, multi-person business game. Oper. Res. 1957, 5, 469–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konczal, E.F. Models are for managers, not mathematicians. J. Syst. Manag. 1975, 26, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Value creation in e-business. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afuah, A.; Tucci, C.L. A model of the Internet as creative destroyer. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2003, 50, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloom, R.S. The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Ind. Corp. Change 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business model design: An activity system perspective. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Massa, L. The business model: Recent developments and future research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Snihur, Y.; Zott, C.; Amit, R. Managing the value appropriation dilemma in business model innovation. Strategy Sci. 2021, 6, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Fifteen years of research on business model innovation: How far have we come, and where should we go? J. Manag. 2017, 43, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Mostaghel, R.; Oghazi, P.; Parida, V.; Sohrabpour, V. Digitalization driven retail business model innovation: Evaluation of past and avenues for future research trends. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L.; Daniel, H.D. What do citation counts measure? A review of studies on citing behavior. J. Doc. 2008, 64, 45–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, W.D.; Griffith, B.C. Scientific communication: Its role in the conduct of research and creation of knowledge. Am. Psychol. 1971, 26, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakso, M.; Björk, B.-C. Anatomy of open access publishing: A study of longitudinal development and internal structure. BMC Med. 2012, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Watson, R.T. Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Q. 2002, 26, xiii–xxiii. [Google Scholar]

- Hedman, J.; Kalling, T. The business model concept: Theoretical underpinnings and empirical illustrations. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2003, 12, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Christensen, C.M.; Kagermann, H. Reinventing Your Business Model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Business models and business model innovation: Between wicked and paradigmatic problems. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.W.; Zhao, Q. Internet marketing, business models, and public policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2000, 19, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doz, Y.L.; Kosonen, M. Embedding strategic agility: A leadership agenda for accelerating business model renewal. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Qu, G. Explicating the business model from a knowledge-based view: Nature, structure, imitability and competitive advantage erosion. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.; Wright, M.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr. The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Schindehutte, M.; Allen, J. The entrepreneur’s business model: Toward a unified perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demil, B.; Lecocq, X. Business Model Evolution: In Search of Dynamic Consistency. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Pistoia, A.; Ullrich, S.; Göttel, V. Business Models: Origin, Development and Future Research Perspectives. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magretta, J. Why Business Models Matter; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities as (workable) management systems theory. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, C. Disruptive innovation: In need of better theory. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2006, 23, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzolla, G.; Markides, C. A business model view of strategy. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Ricart, J.E. From strategy to business models and onto tactics. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iansiti, M.; Levien, R. Strategy as ecology. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 68–78, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Adner, R. Ecosystem as structure: An actionable construct for strategy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A.; Cusumano, M.A. Industry platforms and ecosystem innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobides, M.G.; Cennamo, C.; Gawer, A. Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 2255–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, H.; Lamberg, J.A.; Parvinen, P.; Kallunki, J.P. Managerial cognition, action and the business model of the firm. Manag. Decis. 2005, 43, 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden-Fuller, C.; Morgan, M.S. Business models as models. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.L.; Rindova, V.P.; Greenbaum, B.E. Unlocking the hidden value of concepts: A cognitive approach to business model innovation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosna, M.; Trevinyo-Rodríguez, R.N.; Velamuri, S.R. Business model innovation through trial-and-error learning: The Naturhouse case. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berends, H.; Smits, A.; Reymen, I.; Podoynitsyna, K. Learning while (re) configuring: Business model innovation processes in established firms. Strateg. Organ. 2016, 14, 181–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augier, M.; Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities and the role of managers in business strategy and economic performance. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, P.; Phillips, N.; Jarvis, O. Bridging institutional entrepreneurship and the creation of new organizational forms: A multilevel model. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnsack, R.; Pinkse, J.; Kolk, A. Business models for sustainable technologies: Exploring business model evolution in the case of electric vehicles. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; D’aunno, T. Institutional work and the paradox of embedded agency. Inst. Work. Actors Agency Inst. Stud. Organ. 2009, 31, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H.; Ahlstrand, B.; Lampel, J.B. Strategy Safari: The Complete Guide Through the Wilds of Strategic Management; Pearson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Schoemaker, P.J. Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priem, R.L.; Butler, J.E. Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy Leadersh. 2007, 35, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic managerial capabilities: Review and assessment of managerial impact on strategic change. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1281–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, J. The Disruption Dilemma; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H.; Waters, J.A. Of Strategies, Deliberate and Emergent. Strateg. Manag. J. 1985, 6, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R.; Kapoor, R. Value creation in innovation ecosystems: How the structure of technological interdependence affects firm performance in new technology generations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.F. The Death of Competition: Leadership and Strategy in the Age of Business Ecosystems; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dew, N. Serendipity in entrepreneurship. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 735–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripsas, M. Technology, identity, and inertia through the lens of “The Digital Photography Company”. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I. A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, S.T.; Avolio, B.J.; Luthans, F.; Harms, P.D. Leadership efficacy: Review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 669–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. Strategy and PowerPoint: An Inquiry into the Epistemic Culture and Machinery of Strategy Making. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 320–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Bettis, R.A. The Dominant Logic—A New Linkage Between Diversity and Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 1986, 7, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. The business model as the engine of network-based strategies. In Network Challenge; FIT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, A.; El Sawy, O.A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Venkatraman, N.V. Digital business strategy: Toward a next generation of insights. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’reilly Iii, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Approaching adulthood: The maturing of institutional theory. Theory Soc. 2008, 37, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, C. Sustainable competitive advantage: Combining institutional and resource-based views. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L. Organizational learning research: Past, present and future. Manag. Learn. 2011, 42, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. A theory of organizational knowledge creation. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 1996, 11, 833–845. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Van den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.R.; Winter, S.G. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; Belknap: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Suddaby, R. Editor’s comments: Construct clarity in theories of management and organization. Acad. Manag. 2010, 35, 346–357. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, J.E.; Filatotchev, I. The business model phenomenon: Towards theoretical relevance. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Tucci, C.L. Clarifying business models: Origins, present, and future of the concept. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Spector, B.; Van der Heyden, L. Toward a theory of business model innovation within incumbent firms. SSRN Electron. J. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Spieth, P. Business model innovation: Towards an integrated future research agenda. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 17, 1340001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.; Moingeon, B.; Lehmann-Ortega, L. Building social business models: Lessons from the Grameen experience. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Reuver, M.; Bouwman, H.; Haaker, T. Business model roadmapping: A practical approach to come from an existing to a desired business model. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 17, 1340006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, S.; Kesting, P.; Ulhøi, J. Business model dynamics and innovation: (re) establishing the missing linkages. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiola, M.; Agostini, L.; Grandinetti, R.; Nosella, A. The process of business model innovation driven by IoT: Exploring the case of incumbent SMEs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 103, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.C.; Davidson, R.A. Applications of the business model in studies of enterprise success, innovation and classification: An analysis of empirical research from 1996 to 2010. Eur. Manag. J. 2013, 31, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Zhu, F. Business model innovation and competitive imitation: The case of sponsor-based business models. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateli, A.G.; Giaglis, G.M. Technology innovation-induced business model change: A contingency approach. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2005, 18, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Schilke, O.; Ullrich, S. Strategic development of business models: Implications of the Web 2.0 for creating value on the internet. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtenhagen, L.; Melin, L.; Naldi, L. Dynamics of business models–strategizing, critical capabilities and activities for sustained value creation. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andries, P.; Debackere, K.; Van Looy, B. Simultaneous experimentation as a learning strategy: Business model development under uncertainty. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2013, 7, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkdahl, J. Technology cross-fertilization and the business model: The case of integrating ICTs in mechanical engineering products. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunford, R.; Palmer, I.; Benveniste, J. Business model replication for early and rapid internationalisation: The ING direct experience. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yang, Z.; Ding, J. Metaverse Business Model: Connotation, Classification and Research Framework. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2023, 45, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Snihur, Y.; Zott, C. Towards an institutional perspective on business model innovation. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015, 2015, 11132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felin, T.; Foss, N.J.; Heimeriks, K.H.; Madsen, T.L. Microfoundations of routines and capabilities: Individuals, processes, and structure. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1351–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; Geradts, T.H. Barriers and drivers to sustainable business model innovation: Organization design and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2020, 53, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesen, E.; Berman, S.J.; Bell, R.; Blitz, A. Three ways to successfully innovate your business model. Strategy Leadersh. 2007, 35, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Wang, L.; Chen, J. Toward a Knowledge-based View of Business Model: A Multi-Level Framework and Dynamic Perspective. In The Routledge Champion to Knowledge Management; Chen, J., Nonaka, I., Eds.; Routledge: Abindgon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. The digital transformation of business models in the creative industries: A holistic framework and emerging trends. Technovation 2020, 92–93, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Han, X. Value creation through novel resource configurations in a digitally enabled world. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2017, 11, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R.; Puranam, P.; Zhu, F. What is different about digital strategy? From quantitative to qualitative change. Strategy Sci. 2019, 4, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.M.; Zaki, M.; Feldmann, N.; Neely, A. Capturing value from big data–a taxonomy of data-driven business models used by start-up firms. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 1382–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Dong, J.Q.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallmo, D.; Williams, C.A.; Boardman, L. Digital transformation of business models—Best practice, enablers, and roadmap. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 1740014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.Q.; Netten, J. Information technology and external search in the open innovation age: New findings from Germany. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 120, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snihur, Y.; Thomas, L.D.; Burgelman, R.A. An ecosystem-level process model of business model disruption: The disruptor’s gambit. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 1278–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ao, J.; Qiao, H.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, M. Iceberg Theory: A New Methodology for Studying Business Model from Knowledge Management Perspective. Manag. Rev. 2005, 27, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau, E.; Penard, T. The economics of digital business models: A framework for analyzing the economics of platforms. Rev. Netw. Econ. 2007, 6, 81–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afuah, A.; Tucci, C.L. Internet Business Models and Strategies: Text and Cases; McGraw-Hill Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Weill, P.; Vitale, M. Place to Space: Migrating to eBusiness Models; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, J.; Cantrell, S. Changing Business Models: Surveying the Landscape; Accenture Institute for Strategic Change: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic, O.; Kittl, C.; Teksten, R.D. Developing business models for ebusiness. SSRN Electron. J. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, L.N.; Evangelista, F. Acquiring tacit and explicit marketing knowledge from foreign partners in IJVs. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 1152–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, D.; Sensiper, S. The role of tacit knowledge in group innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1998, 40, 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Y. Knowledge management and new organization forms: A framework for business model innovation. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2000, 13, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykkyläinen, S.; Ritala, P. Business model innovation in social enterprises: An activity system perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyytinen, K.; Srensen, C.; Tilson, D. Generativity in digital infrastructures. In The Routledge Companion to Management Information Systems; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Tang, Q.; Wang, F. Business Model Diversification and the Mechanism of Value Creation: Resource Synergy or Context Interconnection? A Case Study of Meituan from 2010 to 2020. Manag. Rev. 2022, 34, 306–321. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, W. Business Model Innovation Strategy and Hign-quality Development of Enterprises. Q. J. Manag. 2022, 7, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Neukam, M.; Bollinger, S. Encouraging creative teams to integrate a sustainable approach to technology. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 150, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, S.; Pachidi, S.; Sayegh, K. Working and organizing in the age of the learning algorithm. Inf. Organ. 2018, 28, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Boland, R.J., Jr.; Lyytinen, K.; Majchrzak, A. Organizing for innovation in the digitized world. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 1398–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Burger-Helmchen, T. Evolving Knowledge Management: Artificial Intelligence and the Dynamics of Social Interactions. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2024, 52, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R.; Konno, N. SECI, Ba and leadership: A unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. Long Range Plan. 2000, 33, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Number of Journal Articles |

|---|---|

| Initial search total | 242 |

| Duplications | 51 |

| Exclusion based on abstract and intro analysis | 116 |

| Exclusion based on full-text read | 37 |

| Total selected publications | 38 |

| N | Authors | Title | Year | Source | Research Perspective | Core Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amit, R., Zott, C. [7] | Value creation in e-business | 2001 | Strategic management journal | Activity system perspective | Business model depicts the content, structure, and governance of transactions designed to create value through the exploitation of business opportunities. |

| 2 | Zott, C., Amit, R. [11] | Business model design: An activity system perspective | 2010 | Long range planning | Activity system perspective | BMI is the design of a firm’s activity system to achieve a new value proposition. |

| 3 | Hedman, J., Kalling, T. [22] | The business model concept: theoretical underpinnings and empirical illustrations | 2003 | European journal of information systems | Activity system perspective | The business model is conceptualized as a dynamic system of interrelated activities, including resources, processes, and market interactions, where innovation emerges from reconfiguring these behavioral components. |

| 4 | Johnson, M. W., Christensen, C. M., Kagermann, H. [23] | Reinventing your business model | 2008 | Harvard business review | Activity system perspective | BMI is a holistic behavioral transformation achieved through the systematic redesign of four interdependent elements: customer value proposition, profit formula, key resources, and key processes. |

| 5 | Foss, N. J., Saebi, T. [24] | Business models and BMI: Between wicked and paradigmatic problems | 2018 | Long range planning | Activity system perspective | BMI is not a simple linear process, but rather involves complex challenges of wicked problems and paradigm shifts. It requires transcending traditional thinking frameworks and adopting holistic approaches to address uncertainty and multidimensional problems. |

| 6 | Snihur, Y., Zott, C., Amit, R. [13] | Managing the value appropriation dilemma in business model innovation | 2021 | Strategy Science | Activity system perspective | Firms face a behavioral tension between value creation and value appropriation in BMI, which they manage through institutional and cognitive strategies that shape stakeholder interactions. |

| 7 | Konczal, E. F. [6] | Computer models are for managers, not mathematicians | 1975 | Management Review | Knowledge system perspective | Business models should be designed as knowledge-based managerial tools that facilitate decision-making by translating complex data into actionable insights. |

| 8 | Stewart, D. W., Zhao, Q. [25] | Internet marketing, business models, and public policy | 2000 | Journal of public policy & marketing | Knowledge system perspective | Internet business models reshape how knowledge is created, shared, and applied across markets, demanding new frameworks for organizational learning and public policy. |

| 9 | Chesbrough, H., Rosenbloom, R. S. [9] | The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies | 2002 | Industrial and corporate change | Knowledge system perspective | Business models function as cognitive structures that help firms to make sense of technological knowledge and convert it into economically valuable innovation. |

| 10 | Doz, Y. L., Kosonen, M. [26] | Embedding strategic agility: A leadership agenda for accelerating business model renewal | 2010 | Long range planning | Knowledge system perspective | Strategic agility in business model renewal relies on an organization’s ability to process and reconfigure knowledge rapidly, enabled by leadership and collective learning. |

| 11 | Chen, J., Wang, L., Qu, G. [27] | Explicating the business model from a knowledge-based view: nature, structure, imitability and competitive advantage erosion | 2021 | Journal of Knowledge Management | Knowledge system perspective | From a knowledge-based view, business models are composed of structured knowledge assets and routines that determine their imitability and the sustainability of competitive advantage. |

| 12 | Barney, J., Wright, M., Ketchen Jr, D. J. [28] | The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991 | 2001 | Journal of management | Resource-based view | The key to BMI lies in reconfiguring corporate resources or developing new capabilities to support new methods of value creation or operational models. |

| 13 | Morris, M., Schindehutte, M., Allen, J. [29] | The entrepreneur’s business model: toward a unified perspective | 2005 | Journal of business research | Resource-based view | Business models reflect how entrepreneurs configure and leverage internal resources and capabilities to create and deliver value, emphasizing alignment between resources and strategic choices. |

| 14 | Demil, B., Lecocq, X. [30] | Business model evolution: in search of dynamic consistency | 2010 | Long range planning | Resource-based view | Business model evolution depends on the dynamic consistency between resources and capabilities. |

| 15 | Wirtz, B. W., Pistoia, A., Ullrich, S., Göttel, V. [31] | Business models: Origin, development and future research perspectives | 2016 | Long range planning | Resource-based view | BMI is driven by the dynamic development and reconfiguration of a firm’s resource base, highlighting the need for adaptable resource deployment in response to environmental changes. |

| 16 | Magretta, J. [32] | Why Business Models Matter | 2002 | Harvard Business Review | Strategy perspective | Business models are stories that explain how enterprises work and how they create value for customers. |

| 17 | Teece, D. J. [10] | Business models, business strategy and innovation | 2010 | Long range planning | Strategy perspective | BMI is a strategic imperative that enables firms to capture value from innovation by aligning internal activities with external opportunities in dynamic environments. |

| 18 | Teece, D. J. [33] | Dynamic capabilities as (workable) management systems theory | 2018 | Journal of Management & Organization | Strategy perspective | Dynamic capabilities serve as a strategic management framework through which firms continuously adapt, integrate, and reconfigure their business models to sustain their competitive advantage. |

| 19 | Markides, C. [34] | Disruptive innovation: In need of better theory | 2006 | Journal of product innovation management | Strategy perspective | Disruptive innovation challenges existing business models, requiring firms to develop distinct strategic logics and business model responses rather than relying on traditional competitive strategies. |

| 20 | Lanzolla, G., Markides, C. [35] | A business model view of strategy | 2021 | Journal of Management Studies | Strategy perspective | BMI is not only the outcome of strategy, but should also guide strategic direction, especially in highly competitive markets. |

| 21 | Casadesus-Masanell, R., Ricart, J. E. [36] | From strategy to business models and onto tactics | 2010 | Long range planning | Strategy perspective | A business model is a reflection of the firm’s realized strategy, highlighting the logic linking strategic choices. |

| 22 | Iansiti, M., Levien, R. [37] | Strategy as ecology | 2004 | Harvard business review | Ecosystem perspective | BMI must consider the overall health of ecosystems and the role the firm plays within them. |

| 23 | Adner, R. [38] | Ecosystem as structure: An actionable construct for strategy | 2017 | Journal of management | Ecosystem perspective | BMI occurs within ecosystems; firms must understand ecosystem structure and collaborate with ecosystem partners. |

| 24 | Gawer, A., Cusumano, M. A. [39] | Industry platforms and ecosystem innovation | 2014 | Journal of product innovation management | Ecosystem perspective | BMI in platform-based industries stems from a firm’s ability to orchestrate and co-evolve with a broader ecosystem, enabling value creation through shared technological architectures and coordinated interdependencies. |

| 25 | Jacobides, M. G., Cennamo, C., Gawer, A. [40] | Towards a theory of ecosystems | 2018 | Strategic management journal | Ecosystem perspective | Firms can achieve breakthroughs in business models by reshaping ecosystem roles or rules. |

| 26 | Tikkanen, H., Lamberg, J. A., Parvinen, P., Kallunki, J. P. [41] | Managerial cognition, action and the business model of the firm | 2005 | Management decision | Cognitive perspective | Managerial cognition determines the selection and evolution of business models. |

| 27 | Baden-Fuller, C., Morgan, M. S. [42] | Business models as models | 2010 | Long range planning | Cognitive perspective | Business models serve as cognitive instruments that help managers and organizations articulate and communicate their strategic intent. |

| 28 | Martins, L. L., Rindova, V. P., Greenbaum, B. E. [43] | Unlocking the hidden value of concepts: A cognitive approach to BMI | 2015 | Strategic entrepreneurship journal | Cognitive perspective | BMI stems from changes in managers’ cognitive frameworks or mental models. Through redefining business concepts or value logic, firms can uncover hidden innovation potential. |

| 29 | Sosna, M., Trevinyo-Rodríguez, R. N., Velamuri, S. R. [44] | Business model innovation through trial-and-error learning: The Naturhouse case | 2010 | Long range planning | Organizational learning perspective | BMI emerges through trial-and-error organizational learning. |

| 30 | Chesbrough, H. [45] | Business model innovation: opportunities and barriers | 2010 | Long range planning | Organizational learning perspective | Organizational learning capabilities influence a firm’s ability to identify and overcome barriers in BMI. |

| 31 | Berends, H., Smits, A., Reymen, I., Podoynitsyna, K. [46] | Learning while (re) configuring: Business model innovation processes in established firms | 2016 | Strategic organization | Organizational learning perspective | BMI is a learning-by-doing process through which organizations continuously adjust their configurations to understand what can generate new value. |

| 32 | Teece, D. J. [47] | Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance | 2007 | Strategic management journal | Dynamic capabilities perspective | Dynamic capabilities enable firms to continuously create, extend, upgrade, and protect their resource base, thus supporting BMI. |

| 33 | Augier, M., Teece, D. J. [48] | Dynamic capabilities and the role of managers in business strategy and economic performance | 2009 | Organization science | Dynamic capabilities perspective | Dynamic capabilities, including sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring resources, are critical to BMI. |

| 34 | Teece, D. J. [10] | Business models, business strategy and innovation | 2010 | Long range planning | Dynamic capabilities perspective | BMI is the core of strategy and the key for firms to maintain their competitive advantage in rapidly changing environments. |

| 35 | Teece, D. J. [49] | Business models and dynamic capabilities | 2018 | Long range planning | Dynamic capabilities perspective | Firms need to adjust and optimize their business models by continuously developing their dynamic capabilities to adapt to the dynamic changes in the external environment. |

| 36 | Tracey, P., Phillips, N., Jarvis, O. [50] | Bridging institutional entrepreneurship and the creation of new organizational forms: A multi-level model | 2011 | Organization science | Institutional perspective | Institutional entrepreneurship facilitates the emergence of new organizational forms and business models by altering institutional environments. |

| 37 | Bohnsack, R., Pinkse, J., Kolk, A. [51] | Business models for sustainable technologies: Exploring business model evolution in the case of electric vehicles | 2014 | Research policy | Institutional perspective | The institutional environment shapes the paths firms choose for BMI in sustainable technologies. |

| 38 | Battilana, J., D’aunno, T. [52] | Institutional work and the paradox of embedded agency | 2009 | Institutional work: Actors and agency in institutional studies of organizations | Institutional perspective | Firms can innovate their business models through “institutional work” to overcome barriers or reshape rules. |

| The Perspectives on BMI | Associated Mintzberg School(s) | Core Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Activity system perspective | Design School Configuration School | Interdependent organizational activities and system design |

| Resource-based view | Design School | Leveraging internal resources and capabilities |

| Strategy perspective | Design School | Strategic alignment and market positioning |

| Ecosystem perspective | Power School Configuration School | Network orchestration and ecosystem coordination |

| Cognitive perspective | Cognitive School | Managerial cognition and mental models |

| Dynamic capability perspective | Learning School Design School | Sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring in dynamic environments |

| Institutional perspective | Power School Environmental School | Institutional norms and legitimacy pressures |

| Organizational learning perspective | Learning School | Learning through iteration and organizational adaptation |

| Research Topics | Traditional Research on BMI | DBMI |

|---|---|---|

| Connotation | Discusses the changes in business activity systems and business behaviors in terms of value creation, value transformation, and value capture arising from the novelty or scope of business models, through perspectives such as “transaction activities” [7] and “decision-making behaviors” [36]. | Emerging DTs, characterized by their technological knowledge attributes, have become new “innovation elements”, enabling [104] or empowering [105] the evolution of business models through functions such as automation, augmentation, and transformation. This reshapes firms’ business cognition, logic, and modes related to value creation, value transformation, and value capture. |

| Characteristics of process | Focuses on critical process activities and behaviors within BMI, such as research and development (design), implementation (testing), and adjustment (reconfiguration). Particularly emphasizes how external factors, such as institutional and technological environments, influence the innovation process of business models. Highlights the role and mechanisms of experimental actions and learning approaches, including “trial-and-error” and “iteration”, within the innovation process. | The focus is on the surge in innovation elements such as “scale” and “connectivity” driven by digital technology embedding, and the resulting systematic changes induced by innovation processes. Special attention is paid to digital technology features such as “imitability” and “transferability”, significantly lowering the barriers to external knowledge acquisition and expanding its boundaries. The integration of massive user data drastically increases the complexity of business model knowledge, making the utilization of “big data” a central issue in BMI. Traditional innovation models based on physical resources and specific behaviors are increasingly replaced by knowledge creation models relying on digital twins and machine learning. |

| Performance results | Mainly discusses the sources of performance differences in business models: first, the direct impacts by exploring how firm strategies, resources, and capabilities affect BMI performance; second, the indirect impacts by examining the moderating effects of contingent factors such as institutional and organizational contexts. | The primary concern is how embedding DTs leads to performance differences in firms’ BMIs, emphasizing the dual-edged impact of DTs. On the one hand, DTs facilitate access to relevant external knowledge through replicability and standardization; on the other hand, these same characteristics lead to the “competitive imitation” dilemma, making it challenging for innovating firms to prevent imitation, thus easily eroding their competitive advantage. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Jiang, Z.; Qu, G. Digital Business Model Innovation in Complex Environments: A Knowledge System Perspective. Systems 2025, 13, 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050379

Wang L, Jiang Z, Qu G. Digital Business Model Innovation in Complex Environments: A Knowledge System Perspective. Systems. 2025; 13(5):379. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050379

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Luyao, Zhiqi Jiang, and Guannan Qu. 2025. "Digital Business Model Innovation in Complex Environments: A Knowledge System Perspective" Systems 13, no. 5: 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050379

APA StyleWang, L., Jiang, Z., & Qu, G. (2025). Digital Business Model Innovation in Complex Environments: A Knowledge System Perspective. Systems, 13(5), 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050379