Abstract

Data-driven marketing analytics has advanced targeting and optimization, yet its underlying infrastructure now functions as a complex sociotechnical system with overlooked ecological costs. This study conceptualizes programmatic advertising through a systems lens. It introduces the Ecological Delivery Paradox, a structural incongruity where environmentally friendly advertising messages are transmitted via energy-intensive delivery pipelines. Using an interpretivist–abductive design, we conducted 38 in-depth interviews with consumers and professionals, which were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis in MAXQDA. Results show that awareness of hidden delivery costs emerges through a concretization threshold and crystallizes into metaphors such as “clean message, dirty conduit,” which trigger differentiated cognitive–affective pathways. These pathways shape trust trajectories across four profiles: cliff erosion, slow seep, suspended risk, and resilient cores. System-level moderators, including rationalization buffers, efficiency beliefs, and the visibility of low-data alternatives, determine outcomes. The findings extend marketing systems theory by reframing greenwashing as message–infrastructure misalignment and by integrating delivery congruence into advertising trust models. We propose a data-driven control architecture that aligns predictive analytics with ecological proportionality through mechanisms such as lightweight creatives, carbon-aware bidding coefficients, frequency–data quotas, and ad-level transparency labels. This systemic approach advances legitimacy, audience trust, and sustainability as joint objectives in programmatic advertising.

1. Introduction

Data-driven marketing analytics and AI have transformed segmentation, targeting, measurement, and optimization [1]. However, the infrastructure behind them now functions as a complex sociotechnical system. Programmatic advertising (PA) operates through millisecond auctions, standard protocols, measurement and identity layers, and enterprise decision support, creating a multilayer decision environment [2]. This environment is not only about algorithmic accuracy or campaign performance; it is shaped by interdependencies, feedback loops, and externalities that require a systems-thinking lens [3]. Its technical core includes standards such as OpenRTB and real-time bidding (RTB), while the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Digital Markets Act (DMA), the Digital Services Act (DSA), and third-party cookie changes, together with Privacy Sandbox [4], are moving targeting and measurement toward APIs and privacy by design [5,6,7,8]. This transformation creates linked tensions across data integration, real-time decision-making, measurement validity, and ethical responsibility.

A further axis has become salient: the mismatch between green claims in ad content and the energy and carbon cost of the delivery infrastructure. Recent estimates suggest that an average digital campaign emits approximately 5.4 metric tons of CO2, and that programmatic activity in the United States alone may add roughly 100,000 tons per month [9]. Repeated RTB microtransactions, heavy data calls, and creative and measurement payloads generate an often invisible distribution externality that can erode the credibility of eco-conscious messaging. We refer to this as the Ecological Delivery Paradox (EDP). In user cognition, EDP occurs when an ad’s content appears environmentally friendly, yet the way the ad is delivered to users incurs a significant energy and carbon cost. The message appears “green,” but the delivery infrastructure that carries it operates, largely invisibly, in a “dirty” way. In the programmatic ecosystem, each impression triggers multiple auctions, data calls, and tracking pixels, and heavy video creatives consume electricity and generate emissions [10]. These hidden costs create a mismatch between eco-positive claims and the underlying delivery practices. When people notice this contradiction, the brand’s environmental claim weakens, and trust is questioned. Since neglect of these factors can trigger avoidance [11], blocking [12], distrust of measurement [13,14], and legitimacy loss [15].

Existing work in predictive analytics focuses on click and conversion likelihood, reinforcement learning for bidding, and causal decomposition of audience and creative effects [16,17,18,19,20]. These advances often optimize component-level accuracy while leaving system-level feedback, measurement fragility, trust dynamics, and ecological externalities outside the analytical loop, which can produce suboptimal welfare outcomes even when predictions are accurate [21,22,23]. This study addresses a specific gap in the literature on green advertising and digital infrastructures, namely the lack of empirical research on how awareness of the environmental costs of ad delivery infrastructures shapes consumers’ interpretations of ‘green’ claims and their trajectories of advertising trust. This article addresses that gap with two contributions. First, it conceptualizes PA as a complex adaptive marketing system and defines EDP as a system-level phenomenon. Second, it proposes a decision support layer that translates EDP into actionable signals for forecasting trust trajectories and behavioral branches, utilizing features such as metaphor intensity, buffer permeability, efficiency beliefs, visibility of low-data alternatives, and paired transparency cues [24,25]. Accordingly, this study aims to examine how making the hidden environmental costs of digital ad delivery cognitively and affectively salient shapes consumers’ interpretations of ‘green’ advertising messages and their trajectories of advertising trust, drawing on qualitative interviews with consumers and experts in Türkiye. The conceptual framework of the ecological delivery paradox links system thinking with predictive marketing analytics and motivates practical mechanisms, including lightweight creatives, carbon-aware bidding, frequency by data quotas, and ad-level carbon and transparency labels, to align performance, legitimacy, and ecological proportionality.

2. Study Background

Digital advertising has become a significant component of the internet’s energy footprint; yet, the literature treats its environmental costs through largely separate lenses: macro-level measurement of energy and emissions [26], micro-level instrumentation of ad rendering [27], planning frameworks that trade off performance with emissions [28], and supply-side efficiency or contract design [29,30,31]. What is missing is an integrated account that connects how people perceive delivery-layer costs with how markets and designs can internalize those costs without sacrificing effectiveness. As shown in Table 1, existing studies establish critical pieces of the puzzle but stop short of explaining how delivery congruence becomes a trust condition and a design lever in programmatic ecosystems.

Table 1.

Core background studies on environmental impact and governance in digital advertising.

As summarised in Table 1, existing scholarship on green advertising and greenwashing has primarily focused on message-level claims, brand positioning, and consumer scepticism. In contrast, work on data-driven advertising and surveillance infrastructures has analysed issues of privacy, control, and opacity. A third strand has begun to quantify the environmental footprint of digital infrastructures, including programmatic advertising and AI, and a separate body of research conceptualizes the antecedents and dynamics of advertising trust. However, this literature rarely speaks to one another. Prior work has not systematically examined how the environmental implications of the delivery layer intersect with green message claims, nor how the congruence or incongruence between delivery and message shapes the trajectories of advertising trust.

At the macro level, Pärssinen et al. [26] propose a modular framework for estimating energy use and CO2e across internet services, deriving large-scale figures for online advertising, including emissions from invalid traffic. This provides a baseline for the field and makes boundary choices explicit. However, it does not indicate how those numbers should be applied in campaign design, user understanding, or governance signals. At the micro level, González Cabañas et al. [27] introduce CarbonTag, the first browser-side method to approximate energy for a single ad’s rendering. CarbonTag enables per-ad efficiency tiers that inform labels and creative choices. It does not, however, show how such signals affect audience trust or when transparency is sufficient to stabilize acceptance.

However, it is important to note that the present study does not perform a full life cycle carbon assessment of programmatic advertising systems. Instead, we build on recent life cycle assessments and industry reports indicating that the delivery of digital advertisements, including real-time bidding, data calls, and tracking technologies, is associated with non-negligible energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. Our contribution is therefore to examine how making these otherwise invisible infrastructural costs cognitively and affectively salient influences consumers’ interpretations of green advertising claims and their trajectories of advertising trust.

Bridging measurement and management, El Hana et al. [28] advance “emission smart” advertising that aligns media performance and CO2 reduction across planning choices such as formats, pacing, and data intensity. Their framework is managerial and forward-looking, but it leaves the user’s side of the meaning of delivery costs underspecified. Parallel supply-side strands demonstrate that infrastructure can be optimized without compromising performance. Ji et al. [29] demonstrate a hierarchical reinforcement learning controller that reduces energy consumption in production-scale ad systems while improving latency and throughput. This is a powerful lever upstream of the ad experience, yet it does not resolve how downstream users interpret delivery choices. Outside ad-tech, Ankita and Khanna [30] and Xie et al. [31] demonstrate that carbon policy instruments and coordination contracts can align incentives and enhance payoffs in green markets. For example, optimisation of environmental investments and digital marketing campaigns under carbon tax and cap-and-trade policies are linked to carbon regulation to digital marketing intensity, and demand [30]. These studies strengthen the case for internalization, but their focus is on firm or supply-chain strategy rather than the specific semiotic and psychological routes by which audiences form judgments about “green” messages carried by energy-intensive delivery.

Our study addresses a specific gap in empirical research on how awareness of the environmental costs of digital ad delivery infrastructures shapes consumers’ interpretations of “green” advertising and their trajectories of advertising trust by linking delivery-layer environmental signals to audience cognition, emotion, trust, and behavior within a single, testable mechanism. This article conceptualizes the EDP and demonstrates how awareness of hidden delivery processes becomes meaningful in user reasoning, ultimately leading to distinct affective paths. It further shows that a rationalization buffer moderates trust erosion and that delivery congruence, alongside message authenticity and organizational practice, constitutes a third pillar of advertising trust. The result is a conditional architecture that clarifies where interventions can most effectively accelerate trustworthy, lower-impact advertising design.

3. Theoretical Framework

While the previous chapter outlined the empirical and contextual background of digital advertising infrastructures and environmental debates, this chapter develops the conceptual framework that informs our analysis, focusing on the ecological delivery paradox and on how it relates to advertising trust. The framework we develop in this article addresses this gap by linking delivery-layer environmental signals to audience cognition, affect, and trust within a single, testable mechanism. The ecological delivery paradox conceptualizes how awareness of hidden delivery processes and their environmental costs can undermine or reinforce the perceived congruence between ‘green’ messages and the infrastructures that carry them, while the four trust trajectories specify how such perceptions unfold over time in consumers’ narratives.

This study considers PA as an open and complex adaptive marketing system. Decisions made in milliseconds by RTB, identity, and measurement components interact through feedback, delays, and path dependence, so local accuracy does not guarantee system-level viability [21,23,32]. A systems lens, therefore, evaluates outcomes not only by campaign performance but also by welfare and legitimacy under explicit boundaries, acknowledging externalities created along the delivery chain and the well-known drift that can arise from measurement fragility and opacity in intermediated markets [22]. From this perspective, failure to achieve message-infrastructure compatibility can lead to tensions within the system’s subcomponents. Therefore, to maintain system reliability over time, assertions at the message layer must be proportional to the resource load at the distribution layer. At this point, Paradox Theory complements this view by explaining why tensions around green performance and ecological proportionality persist rather than resolve [33].

Paradox theory suggests that green performance and ecological proportionality are not a simple trade-off, but somewhat mutually dependent demands that persist over time [33,34]. In such systems, unilateral efforts to maximize one dimension generate countervailing pressures elsewhere, resulting in oscillation or drift. The goal is not to eliminate tension but to manage it through both-and strategies. Two governance logics follow. First, visibility renders the delivery layer legible, so that claims made at the message layer are verifiable at the distribution layer. Second, internalization embeds ecological costs within decision rules, so that optimisation routines treat them as constraints rather than external afterthoughts. Together, these logics define what “message and infrastructure compatibility” entails in practice: proportionality and accountability that are stable under feedback.

However, in this study, we do not treat the ecological delivery paradox as a laboratory-style independent variable whose effects can be isolated and quantified. Instead, we conceptualise it as an interpretive frame that becomes salient when the often invisible energy use and environmental costs of programmatic delivery are foregrounded. Our analytical focus is on how participants appropriate this frame to make sense of green advertising claims and to narrate shifts in their trust trajectories.

Operationalizing this stance in data-driven predictive marketing requires translating the theory into modellable variables and constraints. In systems terms, delivery intensity, format and frequency choices, and infrastructure telemetry are state variables; transparency practices and cost internalization mechanisms are control variables. The paradox theory provides the admissibility criterion [35] that policies are acceptable when they maintain proportionality and legitimacy while sustaining performance, rather than optimizing a single dimension. Empirically, this becomes a multi-objective optimization or constrained learning problem, with ecological load treated as either a hard or soft constraint, and compliance communicated through credible and consistent signals.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design and Epistemological Position

This study employs a qualitative, interpretivist–abductive design grounded in reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) [36]. The study aims to surface previously unstructured meaning patterns in participants’ accounts and, from these, inductively and abductively elaborate on the conceptual and processual architecture of the emerging Ecological Delivery Paradox (EDP). Abduction enabled iterative “back-and-forth” movements [37]: surprising metaphors, tensions, or dissonant statements in the data were provisionally theorized against extant lenses (greenwashing scholarship, cognitive dissonance, infrastructural invisibility) to generate and refine mid-range explanatory propositions. Accordingly, the design privileges conceptual expansion and mechanism proposition rather than confirmatory (strict deductive) hypothesis testing [38].

Consistent with the reflexive RTA stance, researcher interpretation is treated as an analytic resource; positivist reliability surrogates (e.g., coder agreement coefficients) were not pursued [39]. Instead, analytic transparency was supported through an audit trail, negative case analysis, iterative code reduction, and reflexive memos documenting assumption checks and decision points. These procedures prioritize credibility in terms of interpretive rigor and theoretical coherence over replication metrics.

4.2. Sampling Strategy

We used a stratified, maximum-variation purposive design organized around a two-factor, three-level matrix (a 3 × 3 grid) (see Table 2). The factors were Environmental Concern (EC) and Digital Advertising Exposure and Technical Literacy (DA), each specified at high, medium, and low. Prior research shows that consumers’ responses to digital advertising are shaped not only by message content but also by their broader patterns of digital advertising exposure and strategies of ad avoidance or recovery [11], and that environmental concern and low-carbon goodwill play a central role in how individuals react to low-carbon and environmentally framed initiatives [31]. Building on this work, this study treats environmental concern, digital advertising exposure, and technical literacy as key dimensions that structure how consumers interpret the ecological delivery paradox and respond to green advertising claims. This configuration was intended to elicit contrasting cognitive and affective conditions under which the EDP may emerge or fail to emerge. It also foregrounded three theoretically salient regions: high EC with low DA, where delayed cognitive conflict is plausible; low EC with high DA, which tends to exhibit normalization or rationalization; and mid-level, transitional expressions. Planned negative cases (for example, low-EC and high-DA participants who do not experience the paradox) were included to enable the falsification of the proposed mechanism, rather than merely confirming it.

Table 2.

Participant allocation in the EC × DA sampling framework.

Our sample comprises consumers and advertising/technology professionals. Consumers were recruited to capture lay interpretations of green advertising and the ecological delivery paradox. At the same time, professionals were included to provide reflective accounts of how programmatic delivery decisions are made in practice. Within each group, we employed maximum variation sampling in terms of age, gender, environmental concern, digital advertising exposure, and technical literacy to obtain a broad range of perspectives on the phenomenon.

The target sample comprised 28 to 32 consumers and 4 to 6 contextual professionals, for a planned total of 32 to 38 interviews. This range was justified on three grounds. First, heterogeneity assurance: we sought to populate the core EC-by-DA cells, together with behaviorally distinctive add-ons (ad-block or tracker-block users and digital minimalists), with at least four participants in the theoretically salient cells to avoid idiosyncratic theme inflation. Second, a theoretical saturation protocol was employed, where saturation was operationalized as a decline in the rate of new code emergence [40]. Saturation was assessed iteratively during team coding meetings based on successive batches of transcripts. Once no new higher-order categories appeared, additional interviews were conducted to confirm boundaries and negative cases. Third, reflexive analytic depth: substantially more than about forty reflexive thematic analysis interviews risks analytic dilution (data saturation is not equivalent to analytical saturation), so the upper bound was capped at 38. In practice, we conducted 32 consumer interviews and six interviews with contextual professionals (including ad-technology specialists, media planners, and sustainability/ESG managers), yielding 38 interviews in total. Participant characteristics are reported in Table 3; detailed participant information is provided in Table S1 (Supplementary Material).

Table 3.

Participant characteristics.

In line with the qualitative and theory-building aims of this study, our sampling strategy does not aim for statistical representativeness at the national or global population level. Instead, we purposively selected participants from Türkiye, a context that combines a rapidly expanding programmatic advertising ecosystem, uneven but rising environmental concern, and an evolving regulatory framework influenced by EU directives. Within this setting, we employed maximum variation sampling to capture a broad range of socio-demographic profiles, digital advertising exposure, and environmental attitudes, to develop an analytically transferable account of how consumers construct and contest the ecological delivery paradox.

Participant Selection and Screening Procedure

A brief online screening survey (≈approximately 10 items) was administered to populate the EC × DA stratification matrix. Variables included: (1) average daily online time (categorical: <2 h, 2–4 h, 4–6 h, >6 h); (2) ad formats seen in the past 7 days (video, banner, story/short vertical, native; multiple choice); (3) a four-item EC mini-scale (5-point Likert; summed score later quartiled); (4) ad-block/tracker-block use (yes/no + tool name if any); (5) prior awareness of “PA/RTB” (yes/no); (6) self-rated awareness of targeted advertising (1–5); (7) demographics: age, gender, education, income band, residence (metropolitan/medium city/rural). Composite scores for EC and DA were each divided into four distribution quartiles: top = high, bottom = low, middle two = medium. Purposeful balancing was applied where cell counts lagged (e.g., high-EC/low-DA under-filled). Ad-block users and “digital minimalists” were flagged with secondary labels, acknowledging partial overlap with the DA axis but potential distinctive mechanisms (avoidance rationales, energy/effort framing). To minimize selection bias and avoid artificially priming the EDP, the form excluded evaluative or sustainability-laden terms; notably, “energy” and “carbon” were not mentioned.

4.3. Data Collection Procedure

Interviews were conducted either via secure video or in quiet, in-person settings. Consumer interviews lasted 55–75 min; interviews with professional informants lasted 45–60 min. In-depth interview questions are presented in Table S2 (Supplementary Material). Expert-track adaptations are provided in Table S3 (Supplementary Material). The sequence was: (1) a brief warm-up on everyday digital practices; (2) baseline probes of spontaneous awareness of programmatic delivery and any environmental aspects; (3) a neutral information card outlining the technical RTB sequence and possible energy/CO2 contributions, presented without evaluative cues; and (4) immediate free reflection to capture reframing, metaphors, and affect. Mid-blocks deepened analysis of message–delivery congruence, moral and cognitive emotions (e.g., surprise, unease, guilt, anger, indifference, normalization), trust, and ad acceptance or avoidance; this was followed by responsibility attributions (brand, platform, agency, user, regulator) and transparency demands (e.g., carbon labels, low-data formats).

Two brief contrastive vignettes—one “green” yet data- and energy-intensive video, and one low-data static campaign with carbon reporting—elicited comparative consistency criteria. The neutral information card and the vignette texts are provided in Table S4 (Supplementary Material). Three pilot interviews checked neutrality, clarity, and timing. All sessions were audio-recorded (video was captured only with consent). Consent, confidentiality, and voluntariness were reiterated. Jargon was briefly glossed, unclear points were paraphrased by participants, and a short debrief assessed discomfort and offered non-directive resources.

The information card that introduced the ecological delivery paradox to participants did not provide original measurements of the carbon footprint of their individual ad impressions. Instead, it summarised recent life cycle assessments and industry estimates of the energy use and greenhouse gas emissions associated with programmatic ad delivery. In our design, the card operates as a cognitive and affective trigger that renders the typically invisible infrastructural costs of ad delivery visible to participants, allowing us to trace how such awareness reshapes their moral evaluations of green advertising and their trajectories of trust.

In addition, the information card should not be understood as a neutral description of programmatic advertising, but rather as a light-touch informational stimulus. By summarising existing evidence about the hidden infrastructural work and associated environmental implications of ad delivery in a concise and accessible format, it intentionally primes participants to cross a ‘concretization threshold, making processes that are usually invisible or taken for granted available for reflection. Our analysis, therefore, traces how meaning-making unfolds once this threshold of awareness is crossed, rather than claiming to capture entirely unprompted everyday reactions.

The study received institutional ethics approval. A two-stage consent process was used: an online consent at screening, followed by renewed verbal consent at the start of the interview covering purpose, scope, voluntariness, recording limits, withdrawal rights, and anonymization. Participants were informed that pseudonyms would be used, raw audio and video would be stored in encrypted form with restricted access, and personal or corporate identifiers would be masked (e.g., real company names replaced with category labels). Because the neutral information card could induce brief guilt or discomfort, safeguards included value-free wording, immediate affect checks, and the option to pause or terminate on request. Data handling followed GDPR-aligned principles: identifying data were stored separately under coded keys with access-control logging. To minimize commercial sensitivity, the names of employers and products of professional informants were removed. Power asymmetries were mitigated through brief jargon glosses and dialogic summarising, and reflexive memos tracked process ethics (e.g., avoiding overly dramatic metaphors). A neutral contact was provided for later withdrawal or transcript review.

4.4. Analysis Approach

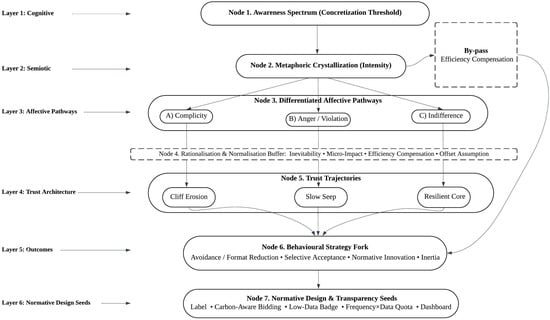

We used RTA to develop a mechanism-oriented account of the EDP [36]. Prior to completing fieldwork, parallel readings refined probing lines. First-cycle “active readings” produced margin notes capturing emerging concepts, affective cues, and putative triggers. We then conducted open coding without an a priori frame, generating mostly in-vivo, concise labels while memoing latent assumptions; the codebook evolution is documented in Table S5 (Supplementary Material). As the code set expanded, semantic overlaps were merged, and low-yield or over-fragmented items were removed. Saturation monitoring (New Code Ratio by block) is reported in Table S6 (Supplementary Material). Emotion codes were reorganized into cognitive and moral sub-clusters (see Table S5, Supplementary Material). We identified seven candidate themes and one boundary pathway labeled Efficiency Bypass (see Table S7, Supplementary Material); definitions and exemplar quotes appear in Table S8, and the mechanism is visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Revised process model of the Ecological Delivery Paradox. Note: Conjunctive transparency (visible low-impact cue ∧ accountable disclosure) is required for a Resilient Core. Dashed box indicates the boundary pattern: an efficiency-compensation suppression variant that operates only under strong efficiency beliefs.

Coding and memo management were conducted in MAXQDA 2022 with versioned decision logs. We established rigor through a documented audit trail, deliberate negative/boundary-case analysis, iterative code reduction, and reflexive memos that recorded assumption checks and decision points, aligning with qualitative trustworthiness criteria of credibility, dependability, and confirmability [41]. Internal coherence and external distinction of themes were checked iteratively, and theme summary tables (including definitions, functional roles, exemplar and deviant quotes, and reflexive notes) guided reporting. Frequency counts remained descriptive, while interpretive weight followed functional centrality and explanatory power.

Sampling adequacy followed a sufficiency/information-power logic rather than statistical saturation [40]. After each interview’s first-cycle coding, we updated the codebook and tracked whether new material extended the conceptual boundaries of core process domains (Awareness/Concretization, Metaphoric Crystallization, Affective Pathways, Rationalization, Trust Mechanisms, Normative Demands). Data collection ceased when additional interviews no longer added higher-order components in these domains; subsequent interviews were used only to probe boundary and bypass explanations (see Table S6, Supplementary Material). Professional informant transcripts served solely as a mechanism for validation and were not merged into consumer themes.

Credibility was strengthened by triangulating data sources (consumer versus professional narratives) [42] and structural triggers (pre- and post-information cards and contrastive vignettes). Transferability relies on thick description, featuring context-rich excerpts that situate platform type, ad-format exposure, and usage routines [43]. Dependability is derived from versioned codebooks, decision logs for merges/deletions, successive thematic maps, and a monitored stopping rule. Confirmability is supported by reflexive memos and explicit documentation of non-activating cases (e.g., efficiency-justification bypass).

Reflexivity & Researcher Positionality

Professional experience in advertising technology provided both analytical advantages, such as technical fluency for clear and neutral explanations, and risks, such as a possible confirmation bias toward emphasizing infrastructural energy and CO2 tensions. Reflexivity was structured along two dimensions.

The first dimension involved temporal reflexive memos (M0 through Mn). The baseline memo (M0) documented a priori assumptions, for example, the expectation that high environmental concern would lead to strong articulation of paradoxes. Subsequent memos recorded instances where data contradicted, nuanced, or failed to support these assumptions, such as high-concern participants normalizing tensions through efficiency justifications. The second dimension addressed vividness mitigation. Striking participant metaphors (for instance, “green shell/dirty engine” or “dirty pipe”) were preserved verbatim but bounded with explicit inclusion and exclusion notes to prevent thematic over-expansion.

During interviews, unsolicited technical elaboration beyond the neutral information card was deliberately avoided [44], while requested clarifications were provided succinctly and without evaluation to reduce framing effects. Reflexive notes also captured moments when specialist knowledge risked overemphasising minor technical distinctions [36,45,46,47]. This structured reflexive protocol enhances transparency by distinguishing participant-derived patterns from interpretive scaffolding, thereby positioning the final model as abductively co-constructed rather than prescriptively imposed.

5. Results

5.1. Thematic Results

The patterns we describe in this section do not represent the frequency or form of spontaneous, unprimed reactions to the ecological delivery paradox in everyday life. Instead, they document how consumers and experts make sense of digital advertising once the ecological dimensions of its hidden infrastructures are foregrounded through an informational stimulus. The ‘concretization threshold’ and ‘metaphoric crystallization’ we observe are thus best understood as interpretive responses that occur when the infrastructural and ecological features of ad delivery are made salient, rather than as naturally occurring baseline responses. In our analysis, we use the term ‘concretization threshold’ to refer to moments in participants’ narratives where abstract awareness of ‘the system’ shifts into a more concrete understanding of specific infrastructural processes and their environmental implications, typically marked by expressions of surprise, moral evaluation, or the use of concrete analogies. ‘Metaphor intensity’ denotes the degree to which participants rely on vivid, often morally loaded metaphors (e.g., ‘leaking pipe’, ‘smoke behind the screen’) to articulate the ecological delivery paradox and its implications for trust. These constructs were not pre-coded variables but sensitizing concepts that were refined inductively during the coding process and applied consistently across the dataset.

To make the results interpretable, we set four boundaries. (1) The neutral information-card intervention separates baseline from triggered discourse; excerpts are tagged BI (Before Information) or AI (After Information). (2) Self-reported behavioural intentions (e.g., willingness to install an ad blocker) are treated as early discursive signals of prospective normative demand, not as verified future behaviour. (3) Because the study is situated in Türkiye’s regulatory and platform ecology, direct generalisation to other markets is limited; transferability is supported through thick, context-rich quotations rather than statistical representativeness. (4) The expert sample provides sufficient linguistic variability to clarify mechanisms but does not constitute a multi-site technical audit of carbon-accounting boundaries; quantitative validation lies outside the scope. Within these boundaries, the results section is organized as an interconnected mechanism architecture. An integrated crosswalk of RQs, core interview items, themes, and exemplar codes is provided in Table S7 (Supplementary Material). Detailed traceability of codes to themes (with exemplar quotes) appears in Table S8 (Supplementary Material).

While our interviews inevitably elicited reactions to the opacity and technical complexity of programmatic advertising, participants’ most pronounced shifts in meaning-making were triggered by the ecological framing of these back-end processes. After engaging with the information card, respondents not only describe ad delivery systems as “complicated” or “hidden” but they repeatedly drew on the language of waste, pollution and moral inconsistency to characterize the energy use and emissions associated with these systems. In this sense, the ecological delivery paradox operates in our data less as a generic awareness of infrastructural complexity and more as a specific interpretive lens that links infrastructural opacity to perceived environmental harm.

5.1.1. Theme 1. Awareness Spectrum and the Concretization Threshold

Participants did not exhibit a simple knowledge versus ignorance divide regarding the environmental costs of programmatic delivery. Instead, their awareness formed a spectrum with four positions: absent, vague hunch, fragmented technical lexicon, and reflexive grasp of the ecosystem. Movement along this spectrum was irregular, and a critical inflection point appeared only when specific cognitive preconditions aligned. Below this threshold, infrastructure felt like inert background noise. Above it, respondents described segmentable, transaction-dense, energy-intensive micro-sequences that supplied the raw material for the later semiotic and affective construction of the EDP.

At the absent pole, roughly one third voiced no baseline questioning: “The ad is just there; I never thought something extra was running.” (C14_BI). The vague hunch group sensed hidden activity without linking it to environmental impact: “Something is being selected back there, I guess, but I never tied it to energy.” (C28_BI). The fragmented lexicon group cited isolated terms such as cookie, bidding, or auction without an integrating schema: “I know there is header bidding; I assumed it was only about speed.” (C05_BI). A small minority displayed a reflexive grasp of the ecosystem: “Servers running must leave some energy trace.” (C18_BI). Even here, the view typically remained a generic data center image rather than reflecting the cumulative effect of repeated RTB cycles.

Crossing the threshold typically follows exposure to the neutral information card (AI). The mental model shifted from static object to dynamic process: “So on each page a little auction swarm runs and decides; that run is electricity.” (C14_AI). Three micro-operations marked this shift: the segmentation of an impression into micro-decisions, the operationalization of verbs such as “decide,” “bid,” and “request,” and energy equivalencing that links processes to electricity consumption. Some participants then reorganized prior fragments into vivid metaphors, while others reached only minimal concretization. Non-crossing explained the absence of later emotional or normative engagement, as in “Even if there is extra processing, that is just basic internet overhead, not worth thinking about.” (C22_AI). Cognitive awareness alone did not produce moral appraisal, so the threshold is necessary but not sufficient for downstream activation.

Two conditions shaped the richness of subsequent metaphoric crystallization. The first was the ability to reconnect earlier technical fragments into a coherent model. The second was the ability to envision a low-data alternative or a lighter format. Analytically, Theme 1 functions as the cognitive intake valve of the EDP model.

5.1.2. Theme 2. Metaphoric Crystallisation of the Paradox

Crossing the concretization threshold seldom left awareness as a simple “list of operations.” About two-thirds of participants translated the dynamic RTB chain into sensory–moral metaphors. These did not serve as decoration but as semiotic transformers: they anchored invisible energy costs in morally charged imagery, forming durable metaphoric crystals that activated distinct moral–cognitive pathways (Theme 3).

A dominant bipolar cluster contrasted “clean message” with “dirty conduit.” After information exposure, the earlier neutral “background” was reframed as polluted: “The slogan sits there all green, but the thing carrying it feels like a sooty tunnel.” (C09_AI). “A shiny organic badge upfront, a muddy engine spun each time behind it.” (C17_AI). These dual images compressed two layers—claimed purity and hidden intensity—creating rapid moral dissonance and accelerating erosion of trust.

A second cluster focused on motion and multiplicity, including swarms, streams, traffic flows, and digital colonies. These metaphors mapped repeated transactions onto kinetic imagery, highlighting cumulative energy demand. One participant shifted from “The ad just loads” (BI) to “Behind each page, hundreds of little bids run and collide—like a tiny traffic jam.” (C14_BI/AI). Another described “a little engine re-starting every time” (C05_AI), dramatizing redundancy and undermining efficiency-based rationalizations.

A third group invoked micro-accumulation and leakage. “Each tiny auction maybe a dot of energy, but millions become a bathtub filling drop by drop.” (C28_AI). This imagery emphasized accounting and measurement rather than guilt, foreshadowing the demands for transparency (Theme 7). Around five participants produced few or no metaphors. For them, the paradox stayed cognitive but emotionally flat: “Technically more processing, sure—so some energy—but it’s just system overhead.” (C22_AI). Mechanical diction here functioned as a buffer, dampening escalation into discomfort or distrust. Two conditions enabled richer metaphor production: (a) reconnecting earlier technical fragments and (b) imagining low-data alternatives. Where either was weak, metaphors remained thin.

Analytically, this theme extends greenwashing studies from message–content mismatches to infrastructural incongruence. Metaphors acted as “code carriers”: “clean message/dirty pipe” legitimized the infrastructure as an ethical concern; “auction swarm” and “engine re-start” dramatized wasteful repetition; “energy leak” supported calls for measurement and labeling. Without crystallization, the paradox lingered cognitively, leaving more room for rationalization (Theme 4). Thus, metaphoric crystallization functions as an affective amplifier between the Concretization Threshold (Theme 1) and Moral–Cognitive Pathways (Theme 3). It determines whether trajectories incline toward complicity and anger or fade into normalization.

5.1.3. Theme 3. Moral–Cognitive Affective Pathways

Metaphoric crystallization transformed a technical mismatch into an experiential trigger, which, for roughly two-thirds of participants, initiated a moral–affective appraisal loop. Processing did not follow a single line of code. It split into three early routing pathways shaped by the tone of metaphors such as “dirty engine” or “micro-auction swarm” and by each person’s environmental self-positioning.

Pathway A was the most common: surprise developed into moral discomfort, which then evolved into a sense of complicity. Contamination or redundancy metaphors intensified this shift. “Once the engine image clicked, it felt like I was needlessly firing a little engine each page… I’m kind of consenting to tiny bits of pollution” (C17_AI). This inward stance personalized responsibility and later supported avoidance intentions such as ad-blocking or a call for carbon labels, while anger stayed secondary and self-directed. Pathway B emerged in a smaller, high-energy subset, where surprise transitioned into anger and violation attribution toward brands or platforms, resulting in early and steep erosion of trust. “If they run that auction traffic each time and tell me they’re eco-conscious, that’s deliberate deception” (C05_AI). Here, external blame narrowed the room for later rationalization. Pathway C characterized many low or non-metaphor producers: brief surprise was followed by pragmatic normalization, as in “If there is extra processing… that’s how the internet works” (C22_AI). Moral energy dissipated, short-term trust held, and normative demand weakened.

Path switching was rare but revealing. C28 initially normalized the issue, then moved to a complexity frame after seeing a low-data alternative: “If a lighter version is possible, not choosing it feels like unnecessary consumption.” This suggests that the visibility of a concrete alternative can moderate the selection of pathways.

Analytically, these routes form an affective routing layer between Metaphoric Crystallization (Theme 2) and Trust Erosion or Resilient Core mechanisms (Theme 5). The discomfort–complicity route links to internalized responsibility and normative demand. The anger–violation route precipitates early trust collapse and external blame. The indifference–normalization route enlarges the Rationalization and Normalization Repertoire (Theme 4) and delays behavioral or normative outcomes. The evidence supports a differentiated affective mediation model rather than a single emotional mediator.

5.1.4. Theme 4. Rationalisation and Normalization Repertoire: The Paradox’s Buffer Layer

This repertoire functions as a discursive buffer that slows or neutralises affect emerging from awareness. Four strands recur, often together. Infrastructural inevitability frames RTB energy costs as unavoidable “physics”, deflecting agency and postponing erosion: “This machine will spin anyway; my noticing won’t stop it.” (C22_AI) Micro-contribution minimisation keeps the paradox cognitively acknowledged but affectively thin: “My one page load is a millionth, basically zero.” (C31_AI) Efficiency compensation reframes added processing as optimisation relative to a broadcast counterfactual: “Without personalisation, there would be random extra ads, total energy could be higher.” (C05_AI) Offset presumption grants provisional credit based on unverified backstage fixes: “If their claim is green, I assume they optimise servers or offset.” (C18_AI).

These strands layer into a defence that steers people away from abrupt avoidance toward slower seep, mid-term transparency demands, or inertia. The shell weakens when a viable low-data option is visible, shifting trajectories toward sharper erosion: “So there is a lighter option; not choosing it means avoidable consumption.” (C22_AI). Where efficiency and offset stories are weak and metaphors are vivid, erosion tends to be a cliff. Where buffering is robust, trust decays slowly.

A minority neutralised the paradox despite high concern or technical awareness by asserting that targeted delivery is not more efficient than old-style bulk diffusion: “Yes, there is processing each time, but compared with mass bombardment it is net more efficient, so it is win-win for me.” (C07_AI). In this pattern, concretisation and metaphor do not trigger erosion. They are absorbed into an efficiency narrative that thickens the buffer and sustains a provisional trust plateau. This boundary case guards against over-determinism and motivates a clear test for future work: whether stronger efficiency beliefs attenuate the effect of vivid process understanding on the speed and slope of trust change.

5.1.5. Theme 5. Trust Fracture Mechanisms and “Resilient Trust” Cores

Trust shifted after emotions and buffering had run their course. Two movements dominated: erosion and a resilient trust core. Participants assessed trust across three layers: message content, organizational practice, and the ecological congruence of delivery. Erosion was sharpest when a green claim sat beside energy-intensive delivery and was read as cosmetic styling. Metaphors converted mismatch into perceived intent, “Up front, the carbon-neutral fairy tale; in back, an engine firing every millisecond, conscious make-up.” (C09_AI). Concealment was treated as an ethical breach, especially on anger or violation paths, “If it were transparent, they’d say it; not saying means they know and hide it.” (C05_AI). A second route appeared as probationary trust, where missing energy or carbon indicators were read as withheld evidence, “If they’re this sensitive, why no simple energy label? Not having it isn’t a crime, but the missing piece chips at trust.” (C14_AI).

Resilience formed when two signals coexisted, an assumption of accountability or offsetting together with a visible low-impact choice. “If the brand chooses static instead of heavy video and I can reasonably assume they keep a carbon report, I believe the claim more.” (C18_AI). This core accepted tension yet framed it as manageable, unlike pure rationalization, which only dampens arousal. Some protected brand trust by relocating responsibility to the platform layer, “It isn’t in the brand’s hands, they get what the platform infrastructure serves.” (C31_AI), which reduced immediate avoidance and redirected attention to structural remedies and regulation.

Trajectory depended on the intensity of the metaphor, buffer strength, and paired signals. Low or indifferent profiles often held trust in suspension; yet, concrete vignette comparisons could revive erosion as delayed complicity. “So there is a lighter option; not choosing it means avoidable consumption.” (C22_AI). Boundary cases showed the fragility of unsubstantiated offset assumptions, “Probably they all do carbon-neutral now anyway.” (C07_AI). Overall, sustainable advertising trust is built on three pillars: message authenticity, organizational practices, and delivery congruence. Resilience requires paired evidence, a visible low-impact cue together with an accountable transparency practice. Lacking either weakens resilience; having both changes the timing and slope of erosion.

5.1.6. Theme 6. Behavioural Strategy Fork

Appraisal, after moving through the cognitive, semiotic, moral, and affective layers, does not end in a single response. It branches into four states: avoidance or blocking, selective acceptance with format optimisation, normative or institutional advocacy, and suspended inertia. The route depends on the emotional pathway, the permeability of the rationalisation buffer, and the trust dynamics described in Theme 5.

Avoidance arises when complicity is salient and trust declines quickly. Participants recast ad or tracker blocking as a small moral defence, not only a privacy move. “I once considered blocking mainly for privacy; now if that engine spins each page, blocking feels like a small brake on needless energy.” (C17_AI) Format-level micro-reduction is common, such as turning off autoplay, lowering resolution, or using data saver. Selective acceptance prevails when paradox awareness is high, but a resilient core remains. People stay in the system while minimising impact by choosing lighter formats and restrained frequency. “If a brand chooses light static over heavy video, I am open to the message; the issue is the inflated format.” (C18_AI) Normative or institutional advocacy emerges when private action is deemed insufficient and a viable alternative is cognitively accessible. Participants call for labels, carbon-aware bidding, and standards that internalise energy costs. “Even if I block, the system runs; the real fix is a CO2 indicator next to ads.” (P4_AI) “If there were a carbon aware bidding parameter, the algorithm could filter high carbon impressions; why not?” (C05_AI) Suspended inertia appears when awareness is present but action stalls through efficiency stories and offset assumptions. “For now, I will watch and see; maybe the industry optimizes anyway.” (C31_AI)

Mechanism logic follows patterned conjunctions. Complicity with a thin buffer produces early avoidance. Anger or violation with rapid erosion produces avoidance or early advocacy when blocking feels too small. Discomfort with a resilient core produces selective acceptance and format optimisation. Indifference with strong rationalization produces inertia. Visibility of a viable low data alternative shifts people toward advocacy or delayed complicity: “So there is a lighter option; not choosing it means avoidable consumption.” (C22_AI) “After seeing the static version, the video looks wasteful.” (C28_AI) Three contributions follow. First, an ethical ad block motive subset grounded in energy and carbon, not only privacy. Second, format optimisation should be considered a distinct sustainability practice within the system. Third, user-seeded normative innovation that includes carbon labels and carbon-aware bidding. These structures can be measured in future scales and tested in structural models.

5.1.7. Theme 7. Normative Design and Carbon Transparency Innovations

Building on Theme 7, participants moved beyond private avoidance to collective, designable fixes that make the delivery layer ecologically consistent. They treated audiences as grassroots co-designers and proposed concrete, user-seeded governance tools. The most frequent idea was an ad-level carbon label that makes invisible RTB costs legible with minimal friction. Two variants surfaced: a numeric indicator in grams of CO2 per ad and a quick color or letter band. Participants acknowledged a precision versus immediacy trade-off and framed it as a testable concept. “I can read calories; why not a tiny CO2 number or colour.” (C14_AI)

A second proposal targeted the auction logic: a carbon-aware bidding parameter that discounts high-intensity inventory by multiplying relevance with a low-carbon coefficient. “If a carbon multiplier enters the bid logic, no one blasts heavy format just because it is cheap.” (C05_AI) A third proposal makes creative choices visible through a low-data certification or a lightweight creative badge that legitimizes selective acceptance. “If I see a light badge, I am more open. It tells me the choice was intentional.” (P2_AI) A fourth combined frequency and data weight into a single quota, so heavy formats consume more of a campaign’s carbon budget. A fifth introduced a post-campaign disclosure panel that reports energy and carbon totals, mitigation or offset actions, and format mix, complementing ad-level signals. “Instant label is speed, panel is accountability. Together they make trust durable.” (C09_AI)

Across proposals, two axes organise the repertoire. The visibility axis turns infrastructure into something legible through labels, badges, and dashboards, which also thins the rationalization buffer. The internalisation axis embeds ecological cost inside prices and quotas, which automates adaptation by design. Not everyone agreed. A minority, anchored in strong efficiency stories, viewed labels as unnecessary complexity and expected industry self-optimization. “The industry will self-optimise; consumers do not need a carbon counter.” (C31_AI) These boundary views highlight two cautions: test cognitive load and label fatigue, and do not assume that more signals automatically yield more trust.

Analytically, the contributions cluster into three layers: transparency semiotics (making the delivery layer continuously visible), internalisation mechanics (embedding ecological cost in optimisation rules), and conditional trust calibration (pairing low-impact cues with credible accountability to stabilize trust).

5.2. Revised Process Model: The Multi-Layered Mechanism of the Ecological Delivery Paradox

This revised process model integrates seven empirically derived themes, along with an efficiency-suppression boundary variant, into a conditional and modular architecture (see Figure 1). It traces how initial infrastructural unawareness can, though not inevitably, evolve into governance-oriented design proposals. The model unfolds sequentially but is not deterministic. Only the Concretization Threshold is required for semiotic and affective activation, while all subsequent transitions remain probabilistic and are mediated and moderated by identifiable linguistic, cognitive, and evaluative conditions.

As shown in Figure 1, the model begins with Node 1, which represents the Awareness Spectrum and the Concretization Threshold. People move from treating delivery as background noise to parsing it as a chain of micro-processes. This shift supplies the granularity needed for later interpretation, yet on its own it rarely triggers emotion. Node 2 is Metaphoric Crystallization. A subset compresses the new understanding into images such as “clean message, dirty conduit,” “auction swarm,” or “energy drip,” which raise affective intensity. Node 3 is the set of Affective Pathways. Appraisal differentiates into three routes: surprise that turns into discomfort and then complicity, surprise that turns into anger with attribution of violation, or brief surprise that is normalized as indifference. Route choice is conditional and can change when a viable low-data alternative becomes visible.

Node 4 is the Rationalisation and Normalization Buffer. Narratives of inevitability, micro-impact, efficiency, and offsets can absorb or deflect emotional pressure; the permeability of this buffer determines how much signal reaches trust. Node 5 is the Trust Trajectory Typology. Outcomes consolidate into four forms: cliff erosion, slow seep, suspended risk, and a resilient core. Resilience requires paired evidence, namely a visible low-impact cue together with credible transparency or accountability. Unsupported offset claims can hold trust only temporarily and often precede a sharper break.

Node 6 is the Behavioural Strategy Fork. Profiles of emotion, buffering, and trust categorize people into avoidance and blocking, selective acceptance with format optimization, normative advocacy, or suspended inertia. Seeing a workable low-data option often shifts inertia toward advocacy. Node 7 captures innovations in Normative Design and Carbon Transparency. Participants seed actionable tools such as an ad-level carbon label, carbon-aware bidding, a low-data badge, a joint frequency-by-data quota, and a post-campaign disclosure panel. The dashed bypass in Figure 1 marks the efficiency-compensation variant, which diverts escalation by folding metaphor and awareness into a net-optimisation story. Table 4 outlines the propositions that connect these nodes into a testable program.

Table 4.

Proposition set for future quantitative testing.

As shown in Table 5, we treat these variables as active parts of the mechanism. Metaphor intensity steers which affective route people take and increases the chance of a sudden trust drop. Buffer permeability determines how strongly emotions translate into changes in trust. Alternative visibility makes it easier to switch paths and to move toward advocacy.

Table 5.

Ecological Delivery Paradox mechanism nodes, moderators, and linked research questions.

Efficiency-belief strength suppresses these effects. Conjunctive signalling—a visible low-impact cue paired with accountable disclosure—helps form a resilient core of trust. In addition, the affective pathways mediate the link between semiotic build-up and the speed of trust change, and the resulting trust trajectory mediates how buffering maps onto behavioural choices.

These trust patterns shape behaviour in the ad environment [48]. People either avoid and block, stay but prefer lighter formats and lower frequency, ask for rules and labels, or remain inert for a time. When a low-data alternative becomes visible, inertia often shifts toward advocacy [49,50]. In parallel, participants propose practical tools for the market itself: an ad-level carbon label, carbon-aware bidding, a badge for low-data creatives, a joint quota that accounts for frequency and data weight, and a post-campaign carbon dashboard. A special case also appears. Strong efficiency beliefs can fold awareness and metaphor back into a net-optimisation story, which suppresses erosion for a while.

Only one step is strictly necessary for the mechanism to start: the concretization threshold. Everything after that depends on five levers that advertisers and platforms can design for: the intensity of metaphors, the permeability of the rationalization buffer, the visibility of lower-data options, the strength of efficiency beliefs, and the presence of paired transparency signals. In practice, weakening efficiency myths, making lighter formats easy to see and choose, and pairing visible low-impact delivery with accountable disclosure can move trajectories away from suppression or drift and toward selective optimisation and workable governance innovations.

6. Discussion

Existing debates on green advertising have primarily focused on congruence between message and practice at the product or corporate operations level (classic “greenwashing 1.0”) [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Our findings introduce the EDP: a delivery-layer incongruity in which an opaque, energy-intensive programmatic distribution pipeline mediates an ostensibly eco-positive claim. This shift extends the locus of evaluative scrutiny from “Is the claim true?” to “Is the communicative infrastructure proportional and transparent?” By theorizing a concretization threshold and metaphoric crystallisation as upstream cognitive and semiotic mechanisms, we explain how an otherwise invisible sequence of RTB auctions, data calls, and tracking pixels becomes morally admissible for judgment. EDP therefore adds an infrastructural dimension to advertising trust models, and crucially, locates the issue within data-driven marketing. Delivery-layer variables, such as creative and data weight, exposure frequency, bidding logic, and disclosure practices, operate as marketing decision levers that jointly shape legitimacy, audience acceptance, and performance.

This study reframes green advertising from product-message alignment to message-infrastructure alignment, placing it squarely on the legitimacy axis of the marketing system. The results show that trust is not a static level but a trajectory that is sensitive to delivery choices and disclosure cadence, which aligns with recent industry moves to co-optimize performance and emissions in media planning. That direction is being codified in practice through measurement and reporting standards, most notably Ad Net Zero’s Global Media Sustainability Framework, which brings channel-level emissions formulae and common data expectations into the planning toolkit and encourages advertisers to treat greenhouse gas estimates alongside established media metrics [51,52]. Although our study does not quantify the environmental footprint of specific ad instances, participants actively drew on the macro-level figures presented in the information card when reassessing their everyday encounters with digital advertising. Several respondents explicitly contrasted the order of magnitude of the reported infrastructure emissions with the seemingly minor eco benefits claimed in green campaigns, thereby constructing the ecological delivery paradox as a perceived mismatch between infrastructural costs and advertised environmental gains.

The finding that a resilient core of trust forms only when visible low-impact cues are paired with credible disclosure is consistent with causal evidence on sustainability information. A recent field experiment demonstrates that carbon-footprint information influences real choices, reducing the carbon intensity of selections by approximately nine percent when the information is presented clearly and accessibly [53,54]. At the same time, research in information systems suggests that transparent disclosure about digital choice architecture does not necessarily weaken the effectiveness of interventions, indicating that openness can be maintained without compromising impact [55]. The mixed record of sustainability labels further underscores that effects are design- and context-dependent, which strengthens the case for standardizing presentation rather than assuming any label will suffice [56,57].

From a systems perspective, the ecological cost of delivery varies materially across channels and formats, and programmatic supply chains contribute a measurable share of sector emissions. Industry analyses estimate substantial monthly emissions from programmatic activity across major economies and map where in the ad supply chain these impacts accrue, which motivates integrating emissions estimates into optimization routines rather than treating them as a separate audit stream [58,59,60]. Emerging frameworks now offer shared assumptions and data flows to consistently calculate media-related emissions, enabling advertisers and platforms to align delivery decisions with standardized metrics instead of bespoke calculators [51]. Our model complements these efforts by identifying which delivery levers are most likely to shift acceptance and trust, thereby connecting accounting-style measurement to marketing outcomes.

Finally, the results imply a regulatory exposure for claims that ignore the delivery layer. In the past two years, regulators and courts have intensified actions against misleading environmental advertising, including airline cases in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands and broader European moves to restrict unsubstantiated “climate neutral” claims, especially those relying on offsetting without evidence [61,62,63]. Aligning message and infrastructure through low-data defaults, carbon-aware bidding rules, and routine post-campaign disclosure, therefore, serves not only efficiency objectives but also regulatory resilience [64,65]. In practical terms, the managerial problem is no longer whether to disclose, but how to operationalize proportional and transparent delivery so that performance, acceptance, and legitimacy are managed together, rather than traded off.

7. Managerial Implications

Findings indicate that trust in “green” campaigns is shaped as much by the delivery infrastructure as by message content. Managers should therefore manage the delivery layer as a set of controllable levers, rather than as a technical afterthought. Specifically, creative data weight and exposure frequency should be treated as primary decision variables [66]. Make low-impact formats the default rather than the exception, and plan media with an explicit carbon budget in addition to CPM and CPA targets [67,68]. Heavy video should incur a higher internal cost of use; when a lighter, static, or compressed alternative can deliver comparable outcomes, the heavier option should be deprioritized. These choices must be clearly visible to the audience [69,70]. Trust stabilizes only when a visible, low-impact cue is paired with accountable disclosure, so campaigns should consistently display a lightweight, creative indicator and provide periodic post-campaign carbon reporting. Table 6 translates the findings into an operational, predictive control system by listing each delivery lever with its model/policy, predictive signals, KPIs, thresholds, automatic responses, and ownership/tooling. Read the table as a sequential decision path: policy or model, predictive signal, KPI, threshold, auto-action, and owner/tooling. Default cut-offs and budgets serve as initial guardrails and should be recalibrated through sequential tests and A/B designs to fit context. When a threshold is exceeded, the specified action operationalizes the finding, for example, prioritizing light formats, adjusting the carbon-aware bid coefficient, or tightening frequency. The ownership/tooling column clarifies accountability and execution. Used in this way, Table 6 operates as a live control panel that links delivery choices to trust, performance, and ecological proportionality. These mechanisms translate participants’ repeated calls for limits on exposure, constraints on data use and reductions in infrastructural “waste” into concrete levers that can be incorporated into programmatic optimisation.

Table 6.

Operational playbook: predictive, data-driven delivery controls.

Media buying and optimization should also be updated to internalize ecological costs. Where platforms allow, incorporate a carbon-aware bidding coefficient and adjust pacing so that frequency and data weight jointly respect the predefined budget. Treat delivery congruence as a KPI in its own right and monitor trust trajectories over time rather than relying on single-point brand lift. When trust erosion accelerates, shift the format mix toward lighter assets and increase transparency intensity; when a resilient core is observed, maintain the disclosure cadence while scaling spend cautiously. Vendor selection and contracts should reflect these priorities: require partners to support lightweight creative standards, frequency governance, and campaign-level carbon panels, and evaluate them based on joint performance and legitimacy rather than price alone.

Finally, experimentation must move beyond message tests to delivery tests. Run controlled comparisons that pit heavy versus lightweight formats under identical targeting, track effects on acceptance and trust as well as on cost and reach, and promote only those configurations that improve both performance and ecological proportionality. Embedding these practices aligns campaign outcomes with audience expectations in sustainability contexts and converts “green” claims from a reputational risk into an operational standard.

8. Theoretical Contributions

This study reframes green advertising from a message-centric view to message–infrastructure compatibility as a primary condition for trust. We formalize delivery congruence as a second signaling channel and instantiate it in a Delivery Congruence Index (DCI) that aggregates the share of lightweight impressions, label visibility, and post-campaign panel completion (weights calibrated via sequential tests). In the predictive layer, the delivery stack is treated as a causal treatment with heterogeneous effects: format, data weight, and frequency are optimized via CATE uplift (heavy vs. light). Trust is modeled as a state variable through a Trust Risk Score (TRS) that forecasts cliff or seep at the subsequent exposure. A carbon-aware bid coefficient (λ) discounts high-intensity inventory within auctions and internalizes ecological cost as a control parameter. Together, these constructs integrate sustainability into multi-objective decision rules and extend existing measurement frameworks by linking delivery metrics to trust trajectories, not only to emissions tallies. Additionally, in this study, these four advertising trust trajectories are reconstructed as ideal-typical patterns from participants’ retrospective and prospective narratives within a single interview setting, rather than measured through repeated observations over time.

We also propose a testable mechanism that explains when hidden delivery processes become morally admissible for judgment and how they destabilize or stabilize trust. Crossing a concretization threshold and subsequent metaphoric crystallization are appraised into three moral–affective pathways, moderated by buffer permeability, efficiency beliefs, and the visibility of low-data alternatives. We identify a dual-signal principle for resilient trust: a visible low-impact cue paired with accountable disclosure outperforms either signal alone, consistent with evidence that accessible carbon information shifts real choices and that transparency can be designed without eroding effectiveness. At the same time, the mixed record of sustainability labels motivates standardization and usability testing [50,51,52,53].

Portability and falsifiability are built in. DCI, TRS, and λ are measurable and can be embedded in sequential tests, constrained bandits, and always-valid monitoring. CATE-based delivery uplift supports policy learning that maximizes ROAS subject to trust and carbon guardrails. In combination with emerging media-emissions standards, this program connects qualitative mechanism discovery to auditable, data-driven delivery governance that aligns performance, legitimacy, and ecological proportionality.

To make the contribution auditable, we formalize the core constructs. DCI aggregates visible delivery-layer signals as

TRS is a next-exposure classifier,

forecasting trust trajectories at t + 1.

A carbon-aware bidding coefficient (λ) internalizes ecological cost within auctions,

FxD captures pacing pressure as

If violation rate is >3%, reduce frequency/reduce creative.

Campaigns operate under a carbon budget constraint,

We thus frame media optimization as a multi-objective problem: maximize ROAS subject to

These definitions make the program falsifiable and deployable: DCI, TRS, and λ can be embedded in sequential tests, constrained bandits, and always-valid monitoring, while CATE-based delivery uplift supports policy learning that maximizes ROAS under explicit trust and carbon guardrails.

9. Limitations and Future Implications

This study relies on an interpretivist, reflexive thematic analysis with interviews conducted in a single national market and a specific platform ecology. The neutral “information card” used to elicit infrastructural awareness may have introduced priming, and several outcomes are self-reported intentions rather than observed behaviors. Professional informants were included to sharpen mechanism interpretation, yet they do not constitute a multi-site technical audit of carbon accounting boundaries. We also do not directly measure delivery-layer energy or CO2 at the impression level; therefore, claims about ecological proportionality are inferred from user reasoning rather than metered infrastructure data. Future research should complement our consumer centred approach with technical measurements of ad tech energy consumption and carbon emissions, for example by combining experimental manipulations of ecological delivery salience with real time metering of programmatic infrastructure, to more precisely quantify the magnitude of the ecological delivery paradox. Finally, trust is examined as a trajectory typology but not tracked longitudinally; slope and persistence are therefore theoretically reasoned, not empirically estimated over time.

Another limitation of this study is that our empirical material is limited to a qualitative, maximum variation sample of consumers and experts in Türkiye. While this design allows us to generate a nuanced account of the ecological delivery paradox in a single, theoretically informative context, the findings are not statistically generalizable to digital advertising markets with markedly different infrastructural configurations, user cultures, regulatory regimes, or levels of environmental concern, such as those in North America, Western Europe, or East Asia. Future research should therefore examine whether and how the ecological delivery paradox manifests in other regions, for example, through comparative studies that combine cross-country samples with mixed methods designs. A further limitation is that our design does not formally distinguish between psychological reactions to the ecological consequences of ad delivery and reactions to the mere complexity or opacity of programmatic infrastructures. Although many participants explicitly anchored their concerns in the environmental figures presented on the information card, future research should employ experimental or mixed-method designs that systematically compare responses to purely technical descriptions of back-end complexity with responses to descriptions that foreground ecological costs, to isolate the distinct contributions of these mechanisms more precisely.

These limitations define a clear empirical agenda. First, the mechanism should be tested with multi-market, preregistered experiments that manipulate creative data weight, frequency, and disclosure, and that track both acceptance and trust alongside CPM and CPA. Second, platform or publisher log data should be paired with defensible carbon estimation methods to quantify delivery externalities at the format and auction level; this enables causal designs such as difference-in-differences, uplift modeling, or contextual bandits to evaluate “carbon-aware” bidding rules in live environments. Third, the qualitative signals distilled here warrant scale development and validation: items for perceived efficiency belief, buffer permeability, alternative visibility, and conjunctive transparency can feed a multi-class classifier of trust trajectories and a moderated-mediation structural model linking semiotic activation to behavior. Fourth, longitudinal panels should estimate the dynamics of “cliff,” “slow seep,” “suspended risk,” and “resilient core,” examining reversion or reinforcement under repeated exposure and disclosure cadence. Consequently, the trust trajectories we propose should be interpreted as narrative-based reconstructions rather than longitudinal measurements, and future research should use longitudinal or field designs to observe trust erosion and repair over time.

A complementary methods track should address measurement validity and governance design. Life-cycle assessment choices and supply-chain boundaries for ad delivery need standardization to avoid gaming and to make ad-level labels credible. Field trials that bind a carbon budget to media plans, publish post-campaign panels, and vary the visibility of “low-data” badges can test whether paired signals reliably shift audiences into resilient trust without eroding performance. Collectively, these steps convert the present mechanism from a qualitative architecture into a decision system that can be audited, optimized, and generalized.

10. Conclusions

This study conceptualizes the mismatch between “green” claims and the energy/carbon cost of the delivery infrastructure as the Ecological Delivery Paradox, and reframes PA as a complex marketing system with feedback, delays, and externalities rather than a set of isolated accuracy problems. Our findings show that crossing a concretization threshold and the ensuing metaphoric crystallization differentiate emotional routes and yield four distinct trust trajectories: cliff, slow seep, suspended risk, and resilient core. These trajectories are conditioned by the permeability of a rationalization buffer, efficiency beliefs, the visibility of low-data alternatives, and paired transparency cues [71]; behavior then branches into avoidance, selective acceptance with format optimization, normative demand, or inertia. In response, we derive an integrated decision-support perspective that jointly optimizes performance, legitimacy, and ecological proportionality.

Managerial and policy implications are direct. Brands and platforms should generate tangible low-impact signals through lightweight creatives and restrained frequency, complemented by ad-level carbon indicators in the moment and post-campaign disclosure dashboards over time. On the market-design side, carbon-aware bidding logics and frequency-by-data equivalence quotas embed externalities into pricing and strengthen selective acceptance, converting suspended risk into resilient trust cores. Future research should operationalize the proposed nodes and conditions as quantitative constructs and test them in causal and experimental designs, validating the effects of metaphor intensity, buffer permeability, and efficiency beliefs on trust slopes and behavioral branching across contexts. The framework offers a practicable roadmap for shifting green programmatic from discursive consistency to infrastructural consistency.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/systems13121059/s1, Table S1. Detailed participant characteristics; Table S2. Core questions and probes; Table S3. Professional (expert) interview adaptations; Table S4. Neutral information card and vignette A/B Texts (verbatim); Table S5. Full Codebook: Ecological Delivery Paradox (EDP); Table S6. Saturation tracking table (New code ratio by block); Table S7. RQ–question–theme mapping matrix; Table S8. Consolidated matrix of codes, themes, and exemplar quotes.

Author Contributions