Abstract

Due to the limitations of general-purpose generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) platforms in meeting the needs of fashion design, AI-based integrated fashion design platforms (AIIFDP) have emerged as a more suitable solution. As the next generation of designers, fashion design students play a pivotal role in shaping the optimization and promotion of AIIFDP. However, research on their continuance intention toward such platforms remains limited. This study constructs an integrated model by combining the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) with the Expectation-Confirmation Model (ECM), and extending it with variables such as personal innovativeness, habit, and perceived intelligence. Using a multi-stage SEM-ANN analysis, the study empirically analyzed data from 486 questionnaires completed by fashion design students in China. The results suggest that satisfaction is the most significant positive factor influencing continuance intention. Moreover, performance expectancy, social influence, perceived intelligence, and habit also exert significant effects. This study broadens the segmented perspective on the application of GenAI in design education and validates the applicability of the extended UTAUT-ECM model in the context of AIIFDP. It also provides theoretical foundations and multi-level strategic recommendations for optimizing AIIFDP products and guiding their integration into educational practices.

1. Introduction

Amid the rapid advancement of industrial digitalization, intertwined challenges—such as lengthy design cycles, creative fatigue, and low design efficiency [1,2]—have impeded the digital transformation of the fashion industry. To address these problems, Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) has been gradually introduced into design processes. In particular, GenAI-based image generation platforms are emerging as key technological enablers for fashion style design and visual expression [3]. This also signifies a shift in fashion design from a human-dominated process to a co-creative model situated within a human–AI interaction system [4]. At the same time, the widespread integration of GenAI in the fashion industry has driven a global shift in fashion design education [5]. Leading institutions abroad, such as Central Saint Martins and Parsons School of Design, have taken the lead in incorporating relevant platforms into their curriculum [6]. In China, fashion design education is actively responding to this trend. High-level institutions such as the School of Design at the Central Academy of Fine Arts have already launched digital fashion courses and experimental teaching modules that incorporate GenAI platforms. In addition, relevant textbooks and fashion design competitions that permit the use of AI have emerged alongside this educational transformation. Within this trend, fashion design students—as the next generation of designers—have become the core user group of GenAI platforms. Although many fashion design students in China have tried using general-purpose GenAI platforms like Midjourney and Stable Diffusion in class, these platforms primarily focus on broad image generation domains like photography and illustration [7], are not designed specifically for the fashion industry. As a result, the substantial gap between generated outputs and students’ expectations—along with the absence of modules tailored to fashion design—undermines their motivation and willingness to continue using such platforms.

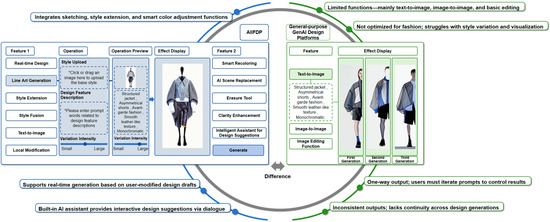

To overcome this technical limitation, Chinese technology firms have recently introduced AI-based Integrated Fashion Design Platforms (AIIFDP), such as LOOKAI and Deep Thinking [8]. These platforms integrate functions like fashion sketch generation and style transformation [9]. Crucially, unlike general-purpose GenAI platforms that produce static, one-way outputs based solely on textual or visual prompts [3], AIIFDP function as intelligent design systems within a human–AI co-creation paradigm. Specifically, AIIFDP adopts a modular design approach and supports interactive design processes. Such features enable real-time generation of fashion renderings from users’ hand-drawn sketches, while also allowing the system to provide intelligent design suggestions—facilitating dynamic exchanges between user creativity and AI-generated output. This interactivity offers more efficient support for creative expression and workflow execution in professional design tasks (see Figure 1 for details). Currently, AIIFDPs (such as LOOK AI) are undergoing rapid development in the fashion industry. Leading Chinese fashion brands, such as ANTA, PEACEBIRD, and ELLASSAY, have already adopted specialized GenAI design systems in their design and development processes. An increasing number of independent designers have also begun using integrated AI fashion design platforms—such as AiDA, an interactive fashion design system developed by The Hong Kong Polytechnic University—to support their creative work and have it showcased at fashion week events [10]. As of 2025, LOOKAI has attracted nearly 100,000 designer users [11] and collaborated with the brand DEMAINZ to present an AI-generated fashion collection at the 2025 China Fashion Week. These trends increasingly indicate that such integrated AI platforms, which consolidate various design functions, are likely to replace general-purpose GenAI platforms as the preferred choice in the fashion industry. This has also become the reason why fashion design institutions in China are paying close attention to and promoting the use of AIIFDP in the classroom, while professional students are increasingly experimenting with it, because it can support their future career development. From a behavioral psychology perspective, AIIFDP, like other interactive creative-generation systems, offers an engaging and structured approach to information generation [12]. This process may trigger several psychological responses among fashion design students, including their perception of consistency between expected and actual performance [7,8,13], perceived intelligence [14,15], reassessment of personal usage habits [16,17,18], and perceptions of personal innovativeness [16,19]. These psychological responses form a “user cognition–behavioral intention” feedback loop, in which Chinese fashion design students’ interactions with AIIFDP influence their willingness to continue using these platforms in design learning and practice. Therefore, such psychological responses are critical and warrant focused attention.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Platform Capabilities and Generated Fashion Designs: AIIFDP vs. General-purpose GenAI Platforms. Note: The image in the blue box (left) was generated by the authors using AIIFDP. The images in the green box (right) were generated by the authors using general-purpose GenAI platforms. The visual representations of platform interfaces are for illustrative purposes only.

While research on the use of GenAI tools or platforms in design has grown in recent years, most studies primarily focus on teaching effectiveness and the enhancement of creative skills. They tend to emphasize the inspirational role of these tools or platforms in coursework and the formation of initial usage intentions [5,20], whereas few have examined the behavioral mechanisms underlying students’ continued use of such tools or platforms following instructional and practical engagement. In addition, many studies have employed mixed samples comprising both design students and industry professionals [21,22]. However, due to differences in professional roles and usage goals, notable differences exist between these two groups in terms of individual perceptions and psychological responses toward the use of AI tools or platforms—differences that may be overlooked in aggregated research findings. Even in studies that focus on students, most research participants are drawn from disciplines such as visual communication, environmental design, or product design [7,23]. No existing research has specifically focused on how fashion design students perceive and utilize AI platforms within educational settings. However, fashion design differs significantly from other design disciplines such as visual communication and industrial design in terms of its focus on design outcomes, types of data input, AI generation logic, and evaluation criteria. For instance, AI-generated fashion solutions are expected to reflect fabric texture and material characteristics [4], whereas visual design typically emphasizes only the aesthetic quality of generated images. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct targeted research specifically on fashion design students. More importantly, the existing literature primarily centers on general-purpose GenAI tools [7,18,24], while AIIFDP—with higher industry compatibility and consolidated functionality—has received limited scholarly attention. In existing studies, external variables such as perceived enjoyment [13] and perceived switching cost [21] have also been shown to influence design students’ willingness to adopt GenAI tools, underscoring the relevance of emotional and cost-related factors. However, most research still relies on models centered primarily on functional dimensions, such as performance expectancy and ease of use. These models have yet to establish a comprehensive, multi-level theoretical framework that systematically and dynamically explains the continuance behavior of design students. Given that the interaction between AIIFDP and fashion design students extends beyond the mere provision of creative outputs—encompassing questions of why, how, and whether students continue to use these platforms, as well as the influence of external conditions—the process may be shaped by a complex set of multidimensional mechanisms. Therefore, capturing the interplay among students’ perceptions of platform effectiveness, cognitive adaptation, external influences, and emotional responses within this human–AI design collaboration system is crucial for the effective integration of such platforms into fashion design education. Without such insight, fashion design institutions risk low instructional efficiency and the eventual marginalization of AIIFDP in educational practice.

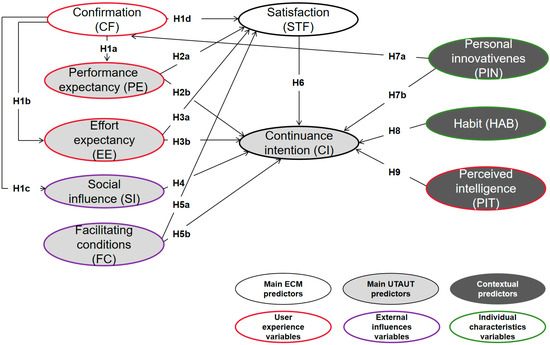

To address the identified research gaps, this study aims to explore the following two questions: RQ1: What types of user experiences, psychological perceptions, technical evaluations, and external factors influence Chinese fashion design students’ emotional responses toward AIIFDP during coursework and creative practices? RQ2: How do emotional responses, individual characteristics, user experiences and psychological perceptions, as well as external influences, shape Chinese fashion design students’ continuance intention to use AIIFDP? To this end, the study integrates the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) with the Expectation-Confirmation Model (ECM) to construct a comprehensive framework. Specifically, the integrated model functions as a dynamic “perception–response” predictive system for continuance intention. In this framework, the core constructs of UTAUT provide the motivational structure for initial engagement, while ECM captures the post-adoption evaluative feedback loop. The measurement items for the core variables of UTAUT and ECM were adapted to suit the context of AIIFDP. Additionally, three context-specific variables—perceived intelligence, personal innovativeness, and habit—were incorporated to enhance the model’s contextual relevance. Specifically, the model incorporates eight external variables across three subsystem levels: (1) at the individual characteristics level, including personal innovativeness and habit; (2) at the user experience and psychological perceptions level, including confirmation, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and perceived intelligence, which collectively assess the impact of users’ cognitive and emotional perceptions; and (3) at the external influences level, including social influence and facilitating conditions. This study addresses RQ1 by examining whether confirmation, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and facilitating conditions serve as antecedents of satisfaction. It further addresses RQ2 by examining how the remaining seven external variables—excluding confirmation—and the endogenous variable satisfaction influence continuance intention. This dual-path research model design enables the integrated framework to both simulate the internal evaluative loop (e.g., performance expectancy → satisfaction → continuance intention) and assess the influence of external variables (e.g., perceived intelligence → continuance intention), thereby establishing a systematic feedback mechanism for understanding Chinese fashion design students’ continuance intention to use AIIFDP. By incorporating dynamic perceptions and user-centric factors such as perceived intelligence and personal innovativeness, the model offers a more nuanced understanding of students’ continuance intention toward AIIFDP. This approach moves beyond traditional technology acceptance frameworks that mainly focus on static cognitive evaluations. In this context, continuance intention is not only an indicator of sustained technology use, but also plays a critical role in explaining students’ cognitive transformation and behavioral intention when engaging with AIIFDP in creative processes.

Building on existing research on technology adoption among Chinese design groups [8,21,25], this study situates the integrated UTAUT-ECM model within the unique context of AI technology acceptance in China—characterized by a growing interest in new AI tools or platforms, a willingness to experiment with them [13], the guiding effect of industry-leading platforms [8], and an educational system that has begun promoting AI-based design tools [7] despite lingering skepticism or even negative perceptions regarding their generative quality [13]. Within this context, the study further examines the applicability, boundary adaptability, and explanatory power of the integrated model. The enhanced model provides a theoretical foundation and localized evidence for understanding technology continuance mechanisms across cultures. Specifically, the study focuses on fashion design education settings, where professional training and practical application are closely linked, to assess how effectively the integrated model explains Chinese fashion design students’ intention to continue using AIIFDP. By uncovering the multi-level psychological and contextual mechanisms that influence continuance intention, this study provides practical guidance for optimizing the functions of AIIFDP as a design interaction system. Furthermore, it promotes a sustainable model of human–AI co-creation that better aligns with students’ cognitive and behavioral needs within educational contexts.

2. Literature Review

2.1. From General GenAI to Specialized AIIFDP in Fashion Education

Currently, with the widespread adoption of Generative Adversarial Networks and diffusion models in image generation, GenAI is rapidly transforming creative industries, particularly fashion design [3]. At this stage, international fashion companies—including luxury brands, designer labels, and fast fashion retailers—are actively incorporating GenAI into their product design and development processes. This growing trend is driving fashion education systems to update and adapt in order to meet the evolving demands of the industry. Leading international fashion design institutions, such as Central Saint Martins and the University of Northampton, have begun integrating GenAI into their design curricula [6,26]. Accordingly, GenAI, as a novel technological input within both the fashion industry and the education sector, has catalyzed structural transformation across several interconnected systems. These include fashion innovation ecosystems, educational training frameworks, and competency development models for students. These international fashion education institutions are placing growing emphasis on students’ ability to flexibly apply GenAI, recognizing it as a core component of their creative capabilities.

Over the past three years, fashion design universities in China have aligned with this wave of international educational reform by beginning to incorporate GenAI into design education. For example, the School of Design at the Central Academy of Fine Arts has introduced interdisciplinary courses such as Digital Fashion Design Research and Future Fashion System Research. Similarly, the School of Fashion Design and Engineering at Zhejiang Sci-Tech University has introduced a micro-major in “Digital Intelligence Fashion Design” and has integrated GenAI platforms into courses such as “Fashion Pattern Design”. In addition, several practice-oriented textbooks—such as “Midjourney AI Fashion Design Creation Guide” and “AI and Fashion Design”—have been widely adopted in university courses. These resources help students integrate GenAI technology into their creative processes. These developments indicate that the influence of GenAI technologies on fashion design education signifies a systemic transformation and adjustment of the Chinese fashion design education model. They also highlight the necessity for pedagogical innovations that support the effective integration of GenAI design platforms into instructional environments.

In classroom settings, fashion design students generally exhibit a strong interest in AI design platforms, reflecting a high level of sensitivity to emerging technologies. The ability to use GenAI platforms is also gradually becoming one of the key competitive skills for students in the future job market [26]. These developments further suggest that GenAI will play an increasingly vital role in the future of fashion design education. However, most mainstream industry-grade GenAI platforms—such as Midjourney and Stable Diffusion—remain primarily image-generation platforms [20]. These platforms typically provide creative inspiration in a static and one-directional manner. General-purpose GenAI design platforms can be enhanced with plugins trained for fashion design. However, they currently support only basic functions like line-drawing coloring and simple style generation. The outputs often fail to match users’ creative expectations and do not support real-time or interactive editing. Consequently, these platforms do not fully meet the specific pedagogical requirements of fashion design education. Their complex operations and unfamiliar technical terminology disrupt the coherence of the educational co-creation system and often discourage students from continuing to use them beyond classroom activities.

With ongoing advancements in innovative algorithms and system-level thinking—such as StyleMe [2] and CrossGAI [9]—GenAI technologies are now capable of supporting multi-module integrated design systems. These systems include functions such as clothing sketch generation, style fusion, and virtual garment display. Building on these technological foundations, Chinese tech companies have recently developed AI-based integrated fashion design platforms (AIIFDP). These platforms incorporate specialized modules—such as sketch-to-illustration generation, rendering conversion, and intelligent style recommendation [8]—into a unified co-creation environment. More importantly, AIIFDP offers interactive features such as real-time illustration generation and creative suggestions. With intuitive interfaces and workflows that better align with fashion design logic, these platforms are attracting growing attention from both the education and fashion industries. Fashion design students are also being increasingly encouraged to engage with these platforms in classroom settings. However, there remains a significant research gap in understanding fashion design students’ continuance intention toward AIIFDP. Specifically, within the human–AI co-creation educational ecosystem, there is a lack of systematic investigation into how psychological perceptions, usage feedback, and environmental conditions interact to influence continuance intention. Against the backdrop of the gradual integration of specialized platforms like AIIFDP into educational settings, this line of research becomes particularly crucial.

2.2. Theoretical Background and Research Model

This study reviews recent research on the behavioral mechanisms underlying the use of AI design tools or platforms (see Table 1), most of which are based on extensions of the UTAUT or ECM models. These studies confirm the explanatory power of these models and support the variable selection and model construction of the present research. Moreover, a substantial portion of recent studies focuses on the Chinese context, indicating that AI design tools or platforms have already gained a certain level of application in China. This also suggests that exploring user behavioral intentions regarding AI design tools or platforms within the Chinese cultural context holds substantial research value.

Table 1.

Research on behavioral intentions toward AI-powered creative and design tools or platforms.

2.2.1. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology

The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) was developed by Venkatesh et al. [27]. This model incorporates four key constructs—performance expectancy (PE), effort expectancy (EE), social influence (SI), and facilitating conditions (FC)—and has demonstrated explanatory power for up to 70% of the variance in user acceptance and behavioral intention [28]. Specifically, PE refers to the degree to which users believe that the technology will enhance their performance; EE captures users’ perceptions of the technology’s ease of use; SI reflects users’ perceptions of how important others view their use of the technology; and FC represents users’ beliefs regarding the availability of external support and resources.

A review of recent studies on behavioral intentions toward AI-based creative and design tools reveals that many adopt the UTAUT framework. These studies consistently confirm that the core constructs of UTAUT significantly influence users’ behavioral intentions [7,8]. In addition, researchers have extended the UTAUT model by incorporating external variables tailored to the characteristics of the study population. Examples include perceived enjoyment [13], perceived risk [8], and personal innovativeness [16], which reflect the influence of emotional responses and individual traits on behavioral intention. For example, Li [22] investigated designers’ continuance intention toward AIGC tools by incorporating perceived anxiety and perceived risk as external variables into the research framework. The findings confirmed that the extended UTAUT model provided more targeted predictive power. Therefore, UTAUT is a well-established theoretical framework for predicting technology adoption. It provides a structured system model for capturing how perceived platform effectiveness, social evaluation, and facilitating conditions collectively shape users’ decision-making processes. Moreover, it allows for the integration of external variables to more comprehensively explain user behavioral intentions. It also helps explain the behavioral intentions and psychological mechanisms of fashion design students in the process of adopting AIIFDP.

2.2.2. Expectation-Confirmation Model

The Expectation-Confirmation Model (ECM), proposed by Bhattacherjee [29], is intended to explain users’ continuance intentions following initial technology adoption. It integrates Expectation-Confirmation Theory (ECT) with the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). The ECM highlights how the consistency between users’ expectations and their actual experiences influences continued usage, focusing on three key constructs: confirmation, perceived usefulness, and satisfaction [21]. Specifically, the model posits that confirmation significantly influences both perceived usefulness and satisfaction. Perceived usefulness serves as a critical determinant of satisfaction, which in turn leads to stronger continuance intention [29]. That is, users’ expectations are re-evaluated through actual experience and individual perception, forming a feedback-driven dynamic mechanism that involves confirmation, belief updating (perceived usefulness), and emotional evaluation (satisfaction).

The ECM has been widely applied in domains such as AI-supported digital technologies [30], smart devices [31], and human–computer interaction [32]. This is attributed to the model’s capacity to capture how users’ cognitive reassessments and emotional feedback evolve through engagement with AI. Empirical studies in these areas have demonstrated the model’s effectiveness in analyzing users’ continuance intentions toward AI technologies and have confirmed the significant influence of its three core constructs: confirmation, satisfaction, and perceived usefulness. Moreover, researchers often integrate the ECM with other theoretical models to better suit their research contexts, particularly when examining users’ satisfaction and continuance intentions toward technology—including in creative design domains [23]. For instance, Fan and Jiang [21] combined the ECM with the Information Systems Continuance Model in their empirical investigation of design students’ and practitioners’ continued use of AI-based drawing tools. Accordingly, adopting ECM as a foundational theoretical framework will also be appropriate for studying fashion design students’ continuance intention toward AIIFDP.

2.2.3. Research Model Integration

Although the UTAUT provides a relatively comprehensive explanation of users’ intentions to adopt AI tools or platforms and demonstrates stronger predictive power than single models such as TAM and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), it does not fully capture fashion design students’ continuance intention toward AIIFDP. This limitation arises from the UTAUT’s primary focus on users’ initial decision-making during the technology adoption phase. Due to the limitations of its framework, it overlooks post-adoption experience-related factors such as user satisfaction and emotional responses [32]. In contrast, the ECM centers on evaluating users’ behavioral intentions regarding continued technology usage [31]. However, it does not incorporate other critical dimensions that influence technology adoption, such as social influence from external sources. As a result, the ECM alone also falls short of fully explaining the mechanisms underlying users’ technology adoption decisions [32]. Therefore, neither UTAUT nor ECM, when used in isolation, provides a sufficiently comprehensive explanatory framework.

Thus, integrating UTAUT and ECM offers a viable approach to addressing the limitations inherent in each standalone model. This integration enables the formation of a multi-stage explanatory system that links users’ initial perceptions of usage to their continuance intentions and traces the user journey from adoption to sustained use. Prior studies in the fields of digital technologies and mobile information services—such as digital democracy platforms [33], mobile payment systems [34], and mobile health applications [35]—have demonstrated the strong predictive performance of the UTAUT-ECM integrated model. These findings demonstrate the adaptability of this integrated model across different technological ecosystems, highlight its scalability in complex human–application interactions, and provide theoretical support for constructing an integrated model tailored to the AIIFDP context in this study.

However, within the specific context of AIIFDP—an AI-driven technology—the existing integrated UTAUT-ECM model still fails to account for several critical cognitive and individual trait dimensions. One such factor is the perceived intelligence of AI, which refers to users’ subjective perception of the system’s intelligence and human-like capabilities. This perception has been shown to significantly influence behavioral intention [36]. Secondly, personal innovativeness has been identified as a key determinant in prior studies on emerging digital technologies [16,37]. In addition, habit has been validated as a crucial and often non-rational predictor of technology acceptance and usage, especially in the context of AI technology adoption [38]. The variables related to AI efficacy perceptions and individual characteristics are operated as sub-systems nested within the UTAUT-ECM structure, enabling a more in-depth modeling of the interaction between users and AIIFDP.

Therefore, this study integrates UTAUT and ECM to investigate the continuance intention toward AIIFDP within the context of design education. To further improve the model’s predictive capability and explanatory scope, three additional variables—perceived intelligence, personal innovativeness, and habit—are incorporated. These three external variables not only reflect the technical attributes of AIIFDP but also capture individual differences that shape users’ continued usage. In addition, the integrated model includes seven predictive variables from UTAUT and ECM: performance expectancy (PE), effort expectancy (EE), social influence (SI), facilitating conditions (FC), confirmation (CF), satisfaction (STF), and continuance intention (CI). This not only demonstrates the replicability of well-established theories but also aligns closely with the specific context of this study—fashion design students’ use of AIIFDP. The inclusion of these variables ensures both the theoretical reliability and contextual relevance of the integrated model constructed in this study, thereby extending the original UTAUT-ECM model. In addition, given the conceptual and measurement overlap between perceived usefulness in ECM and performance expectancy in UTAUT, perceived usefulness mainly concerns users’ perception of the technology’s ability to enhance task efficiency and outcomes [23], while performance expectancy emphasizes users’ belief and expectation that the technology will improve task performance or help complete tasks [39]. Given the outcome-oriented nature of fashion design education, performance expectancy is more closely aligned with the core objective of the model—namely, predicting students’ expectations regarding the actual effectiveness of using AIIFDP in creative design practices. Therefore, this study chose performance expectancy over perceived usefulness, as it is more context-sensitive and aligns with the approach adopted in related research [40]. This choice improves the theoretical consistency and coherence of the integrated model, while also reducing redundant integration and enhancing the structural simplicity. Based on this integration and extension, the research model presented in Figure 2 is developed to systematically investigate Chinese fashion design students’ continuance intention toward AIIFDP.

Figure 2.

Theoretical model.

2.3. Hypothesize Development

2.3.1. Confirmation

Confirmation (CF) refers to users’ perceived consistency between their actual experience with a technology and their prior expectations [29,40]. In the ECM, confirmation is considered a key antecedent of both perceived usefulness and satisfaction, indirectly affecting continuance intention [29]. Existing studies have confirmed that in contexts such as AI-generated painting and content automation, confirmation significantly enhances users’ perception of technological effectiveness and satisfaction [14], and also influences their evaluation of the social influence associated with adopting AI tools [16].

In the context of AIIFDP, Chinese fashion design students may find that their learning and practice experiences surpass their initial expectations. When this occurs, they are more likely to recognize the platform’s efficiency and value, accept recommendations from peers, and feel satisfied. On this basis, this study puts forward the following hypotheses:

H1a.

CF positively influences performance expectancy.

H1b.

CF positively influences effort expectancy.

H1c.

CF positively influences social influence.

H1d.

CF positively influences satisfaction.

2.3.2. Performance Expectancy

Performance expectancy (PE) refers to users’ belief that employing a specific technology will enhance their learning or work-related outcomes. The UTAUT predicts that performance expectancy is the strongest predictor of behavioral intention [39]. Recent studies in the domain of GenAI technologies have also confirmed a positive association between PE and designers’ willingness to adopt AIGC tools [13,22]. Moreover, research in fields such as mobile technology and virtual reality has shown that PE positively influences satisfaction [41,42]. In design education, students’ satisfaction with new technologies is often related to improvements in design efficiency and creative expression.

The fashion industry operates in a market that places a high value on both efficiency and quality. Similarly, when simulating real-world design tasks, fashion design students expect AIIFDP to deliver efficient and high-quality output. Therefore, based on the UTAUT framework, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2a.

PE has a positive relationship with satisfaction.

H2b.

PE has a positive relationship with continuance intention.

2.3.3. Effort Expectancy

Effort expectancy (EE) refers to an individual’s perception of how easy it is to use a new technology, including the time and effort required to master it [8]. Within the UTAUT framework, EE captures users’ perceived ease of use, which subsequently influences their user experience, satisfaction, and intention to adopt the technology. This mechanism remains critical in both learning environments and contexts involving new technologies. Existing studies on AI technology adoption have confirmed that EE significantly enhances user satisfaction [42] and serves as a consistent predictor of continuance intention [43].

In the context of AIIFDP usage, if fashion design students perceive the platform as user-friendly—with intuitive workflows and a low learning curve—they are more likely to have a positive user experience and remain engaged in its use. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3a.

EE significantly influences satisfaction.

H3b.

EE significantly influences continuance intention.

2.3.4. Social Influence

Social influence (SI) refers to an individual’s perception of whether important others—such as superiors, elders, or peers—expect them to adopt a particular technology. It typically reflects normative social pressure [39]. Within the UTAUT framework, SI is recognized as a key factor influencing behavioral intention, often exerting an even stronger effect in group-oriented or educational contexts. Recent studies in design education contexts have confirmed that SI significantly influences students’ adoption of GenAI tools [7].

Fashion design students are likely to be influenced by the expectations of their teachers and peers [44]. They may also continue using AIIFDP due to the recognition that adopting such platforms aligns with broader trends in the fashion industry. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

SI positively and significantly impacts continuance intention.

2.3.5. Facilitating Conditions

Within the UTAUT framework, facilitating conditions (FC) are identified as a key determinant of user behavioral intention. In the context of AI technology adoption, FC refers to individuals’ perceptions of the internal and external resources available to support their use of AI tools [8]. Users with more positive perceptions of such conditions are more likely to adopt and use AI technologies—a conclusion also supported by studies in the design domain [22]. Li et al. [8] also highlighted the positive impact of FC on the willingness of professionals in the fashion industry to continue using AI-Generated Content Tools. Moreover, prior research on technology acceptance and continuance intention has consistently demonstrated a strong positive relationship between FC and user satisfaction [42].

In fashion design education, the availability of teaching resources and the quality of training related to AIIFDP—as reflections of FC—may significantly influence students’ continuance intention. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5a.

FC significantly influences satisfaction.

H5b.

FC significantly influences continuance intention.

2.3.6. Satisfaction

Satisfaction (STF) refers to a user’s subjective evaluation of the discrepancy between their actual experience and initial expectations after using a technology [29]. According to the ECM, STF is a key driver of users’ continuance intention. In UTAUT-based research, STF often functions as a mediating variable and is recognized as one of the strongest predictors of behavioral intention [42]. The link between STF and continuance intention has been extensively validated in AI-supported domains. Studies on AI-enabled mobile banking [30], AI-based chatbots [31], and AI voice assistants [32] consistently demonstrate a significant positive association between STF and continuance intention.

When AIIFDP enhances fashion design students’ learning efficiency, creative expression, or the quality of their design outcomes, they are likely to develop a positive user experience and emotional evaluation. Such positive evaluations are likely to promote their continuance intention toward AIIFDP. Building on this, the study presents the following hypothesis:

H6.

STF positively and significantly impacts continuance intention.

2.3.7. Personal Innovativeness

Personal innovativeness (PIN) is defined as an individual’s tendency to explore and actively adopt new technologies when facing them [45]. In research on technology acceptance, PIN—as an individual trait—has been shown to influence users’ willingness to adopt emerging technologies. Yu et al. [16] found that individuals with higher PIN actively interact with AI drawing applications, which significantly enhances their sense of confirmation. In addition, in fields such as digital technology, PIN has been identified as an important determinant of adoption intention [46]. Twum et al. [37] also emphasized that PIN plays a key role in shaping university students’ intention to use e-learning.

Based on the above research findings, we propose a reasonable inference: fashion design students with a more innovative and experimental mindset are likely to hold positive perceptions of the use and effectiveness of novel AIIFDP, which in turn encourages their continued use of such platforms. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H7a.

PIN significantly influences confirmation.

H7b.

PIN significantly influences continuance intention.

2.3.8. Habit

Habit (HAB) refers to the extent to which automatic behavior is developed through repeated learning and use of a technology [47]. HAB has been shown to be a key predictor of technology usage. In the context of AI technologies, Al-Emran et al. [38] found that HAB positively influences users’ willingness to use AI chatbots. This finding underscores the critical role of HAB in AI technology adoption and highlights users’ growing reliance on such tools. As Venkatesh et al. [27] noted, individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors that have become habitual. Therefore, based on previous research findings, students who have already developed a habit of using GenAI platforms are more likely to continue using AIIFDP, especially given its more focused and enhanced functionalities. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H8.

HAB has a positive relationship with continuance intention.

2.3.9. Perceived Intelligence

For AI technology, perceived intelligence (PIT) refers to users’ subjective perception of its level of intelligence and human-like capabilities. This includes the system’s efficiency in understanding user needs, response speed, knowledge retrieval, and autonomous reasoning capabilities [36]. Prior research in digital technologies, such as voice assistants, has shown that PIT significantly and positively influences behavioral intention [36]. Human-designed products are often preferred because human designers are believed to possess superior cognitive abilities and intentional planning [48]. Therefore, the level of intelligence demonstrated by AIIFDP—such as its ability to emulate professional designers, interact with students, and autonomously generate fashion design proposals based on their needs—may enhance students’ continuance intention. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H9.

There is a notable positive effect of PIT on continuance intention.

3. Research Methods

Considering the multi-level psychological and contextual perception mechanisms generated by Chinese fashion design students when interacting with AI-based integrated fashion design platforms (AIIFDP). This study adopts a comprehensive empirical approach to explore the influencing factors and underlying mechanisms of Chinese fashion design students’ continuance intention toward AIIFDP. By integrating the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) and the Expectation Confirmation Model (ECM), and drawing on a thorough review of relevant literature on AI tool adoption, a composite research model consisting of 10 key variables was ultimately developed. This study employed a structured questionnaire for data collection, with a pre-test conducted prior to the formal distribution to improve the quality of the instrument. A stratified random sampling strategy was also adopted to select fashion design students with experience using AIIFDP as respondents. In the data analysis phase, this study adopted a two-stage hybrid approach. First, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to assess the validity of the composite model and to test the hypothesized relationships between variables. Second, an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) analysis was conducted to capture potential nonlinear associations among variables and to rank the relative importance of the predictors. This SEM-ANN hybrid analytical approach enhanced the robustness of behavioral intention modeling.

3.1. Questionnaire Design and Measurement Instrument

The questionnaire used in this study consists of two sections. The first section gathers demographic information, including gender, age, education level, and city tier. The second section focuses on assessing respondents’ psychological perceptions, as well as their views on personal characteristics and external influences. Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree), allowing for a nuanced evaluation of fashion design students’ perceptions of effectiveness, external influences, attitudes, and behavioral tendencies toward AIIFDP as a human–AI intelligent interactive design information system in the context of coursework and design practice.

With the exception of personal innovativeness, habit, and perceived intelligence, the measurement items for the remaining seven variables are derived from the UTAUT and ECM frameworks. These ten variables are adapted from established scales used in recent empirical research on the usage of AI tools or platforms. The items were appropriately modified to reflect the context of AIIFDP and to align with fashion design students’ actual learning and design experiences. As a result, the ten variables are more targeted than those in general technology acceptance models. The complete measurement items are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measurement scales for constructs.

Specifically, performance expectancy (PE) refers to fashion design students’ subjective perception of the anticipated benefits of AIIFDP in enhancing their design efficiency, creative expression, and the overall quality of their work. This variable is measured using four items that reflect their general perception of AIIFDP’s effectiveness and value. Effort expectancy (EE) captures students’ perceived ease of use when operating AIIFDP. It is also measured with four items, focusing on the ease or difficulty of mastering the platform. Social influence (SI) refers to the extent to which students believe that influential figures—such as instructors or industry mentors—recognize and support their use of AIIFDP in educational and creative contexts. It is assessed using three items that capture the impact of perceived social approval. Facilitating conditions (FC) are measured by four adapted items that examine students’ perceptions of whether factors like institutional training and technical infrastructure support their use of AIIFDP. The items for these four variables are adapted from Li et al. [8] and Li [22].

In addition, the constructs of confirmation (CF) and satisfaction (STF), each measured by four items, are adapted from the scales developed by Liu and Huang [23] and Ghazali et al. [32]. CF captures students’ subjective assessment of how well the actual performance of AIIFDP matches their prior expectations. STF reflects students’ overall experience when using AIIFDP, with an emphasis on the perceived value of the platform and their emotional responses.

In the context of this study, the three items measuring perceived intelligence (PIT) are adapted from the scale developed by Zhao et al. [36]. These items are designed to capture respondents’ perceptions of AIIFDP’s intelligent capabilities in understanding design requirements, providing interactive feedback, and autonomously generating creative proposals.

Personal innovativeness (PIN) reflects students’ willingness to explore, adopt, and actively experiment with emerging technologies like AIIFDP. This construct is measured using three items. Habit (HAB) reflects students’ tendency to use GenAI tools or platforms automatically during design activities and is assessed through three items that evaluate the naturalness and consistency of such habitual use. Both constructs are adapted from Yu et al. [16] and tailored to the AIIFDP context to capture how individual characteristics influence students’ continuance intention.

Continuance intention (CI) refers to fashion design students’ willingness to continue using AIIFDP in their coursework and creative practice. It reflects their cognitive inclination and behavioral intention regarding future use of the platform. This variable is measured using four items adapted from Fan and Jiang [21].

To ensure linguistic accuracy and cross-cultural applicability, this study employed a bilingual translation procedure. The English items in the references were first translated into Chinese and then adapted to the AIIFDP context before being distributed to Chinese students. To ensure semantic equivalence between the Chinese version used in the survey and the English version presented in the paper, a graduate student majoring in English conducted a back-translation, which was subsequently reviewed for clarity and semantic consistency by two design researchers.

3.2. Pre-Test and Data Collection

Before distributing the formal questionnaire, a pre-test was conducted. Initially, two graduate students from non-fashion design disciplines were invited to review the questionnaire to ensure that all items were clear and unambiguous. Subsequently, from 1 December to 21 December 2024, a pilot survey was conducted with 32 undergraduate and 18 graduate students majoring in fashion design-related fields at Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, resulting in a total of 50 responses. After excluding invalid responses, 42 valid questionnaires remained, resulting in a response rate of 84.0%. The overall Cronbach’s α was 0.935, with individual constructs ranging from 0.733 to 0.883, indicating good internal consistency and measurement reliability across all dimensions. Subsequently, the formal questionnaire was distributed through the Credamo online platform to facilitate data collection. The target respondents were fashion design students in China who had previously used AIIFDP (such as Fashion Diffusion, Style3D Moda or LOOKAI) in their coursework or design practice. To ensure sample representativeness, stratified random sampling was employed, recruiting participants from multiple academic levels across institutions including Donghua University, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, China Academy of Art, Jiangnan University, Shaoxing University, and Nantong University. Due to the leading role of the apparel industry clusters in the Jiangsu-Zhejiang-Shanghai region in driving industrial digital transformation and the growing demand for digital talent [49,50,51], there are more professional institutions in this region offering fashion design courses centered around AI technologies compared to those in central and western China. These institutions are also more active in developing AI-focused design textbooks and establishing micro-majors related to AI fashion design. Therefore, among the institutions in the Jiangsu-Zhejiang-Shanghai region sampled for this study, students with actual experience using platforms like AIIFDP are likely to be more concentrated. This sampling approach ensures that respondents possess a certain level of usage experience and practical needs, enabling them to provide valuable feedback. The purpose of the study was clearly explained to the students, all of whom voluntarily participated and signed a digital informed consent form.

To ensure that all respondents shared a consistent understanding of the concept and specific features of AIIFDP, participants were asked to engage in a 15–20 min hands-on trial with LOOKAI (a representative AIIFDP, https://app.look-ai.cn/ (accessed on 2 October 2025)) before beginning the questionnaire. Additionally, they were shown an electronic presentation outlining the functions of AIIFDP, accompanied by interface screenshots to provide a clear and intuitive context for the survey. The survey was conducted from 12 January 2025 to 28 May 2025. The completion time was approximately 6–10 min, and a small cash incentive was offered as a token of appreciation. A total of 511 questionnaires were collected, with invalid responses excluded during the screening process. Specifically, questionnaires with excessively short completion times (less than 180 s) or obvious patterns of invalid responses (e.g., selecting the same option for all items) were removed. After this filtering, 486 valid responses remained, resulting in a validity rate of 95.1%. All collected data were anonymized and used exclusively for academic purposes. Demographic details are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Respondent demographic details.

3.3. Data Analysis

This study adopted a hybrid approach combining PLS-SEM and ANN. PLS-SEM is a method of SEM used to test the underlying relationships in the research model. It is suitable for exploratory research, theory development, and investigating interactions among variables in complex models, and has been widely applied in the field of user behavior research to validate hypothesized relationships [13,25,38]. However, SEM can only identify linear causal relationships between variables, which may lead to an oversimplification of the complex psychological mechanisms and decision-making intentions that arise when users engage with new technologies and platforms. This limitation can be addressed by introducing the ANN model as a complementary analytical technique, as the ANN is capable of capturing potential nonlinear relationships among variables that influence user satisfaction and behavioral intention. Specifically, the ANN model employed in this study is based on the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) architecture [52], which enables nonlinear mapping of input data through differentiable activation functions [53], and extracts data features layer by layer using multiple interconnected neurons. Meanwhile, Feedforward Backpropagation (FFBP) was used to train the MLP, enabling iterative optimization of parameters to capture complex nonlinear relationships within the data. This approach enhances overall predictive performance [54] and provides more valuable guidance for research-driven decision-making. At present, the SEM-ANN hybrid method [55] has become increasingly common in recent research, particularly for testing hypotheses and predicting behavioral intentions toward new and emerging technologies [56,57,58], providing a more comprehensive understanding of both theoretical and practical outcomes.

At the operational level, SmartPLS 4.1 was used to conduct the PLS-SEM analysis. The maximum number of iterations was set to 3000, and default initial weights were applied. Additionally, bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was used to assess the statistical significance of the results [59]. The ANN analysis was conducted using SPSS R26.0.0.0. Variables identified through PLS-SEM as having significant effects on satisfaction and continuance intention were used as covariates and input into the neural network. Satisfaction and continuance intention were each set as dependent variables. In the partitioning of the dataset, the ratio of “training” to “testing” was adjusted to 9:1. Next, in the customized architecture, the number of hidden layers was set to one to ensure effective deep learning at the output nodes [57]. The activation function for both the hidden layer and the output layer was set to the sigmoid function, and the training optimization algorithm was set to gradient descent.

4. Results of Data Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

4.1. Assessment of Measurement Model

An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was first conducted on the newly developed composite scale. The results supported the proposed model comprising 36 items and 10 factors, with a total variance explained of 73.985%. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.926, and the communalities ranged from 0.643 to 0.810. All EFA loadings were between 0.713 and 0.862 (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Metrics for examining the consistency and construct accuracy within the measurement framework.

Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess common method bias (CMB) [59]. An unrotated factor analysis revealed that the first factor accounted for 32.581% of the total variance, well below the 50% threshold, indicating that CMB is unlikely to threaten the validity of the results. Additionally, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each predictor variable was calculated. As shown in Table 4, all VIF values were below 5, suggesting that multicollinearity was not a concern [60].

Assessing the measurement model also requires a thorough evaluation of its reliability and validity. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were used to assess the internal consistency of all core constructs. The values ranged from 0.809 to 0.904 (see Table 4), all exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.7 [61]. In addition, the composite reliability (CR) for all variables was above 0.8, also surpassing the standard criterion of 0.7 [62].

Furthermore, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values for all constructs in this study were above 0.693, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.5 [63]. These results confirm that all constructs meet the criteria for convergent validity, supporting their suitability for subsequent structural analysis.

4.2. Assessment of Structural Model

Assessing cross-loadings is generally regarded as a preliminary step in validating a structural model, as it helps establish discriminant validity [60]. In the composite model developed for this study, the square roots of the AVE for all constructs ranged from 0.832 to 0.881. These values are substantially greater than the inter-construct correlations (see Table 5), meeting the Fornell-Larcker criterion for discriminant validity [64], with no cross-loading issues present. Collectively, these results confirm that the newly developed scale demonstrates strong discriminant validity.

Table 5.

Results of discriminant validity test.

Finally, the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratios observed in the sample ranged from 0.282 to 0.596, well below the recommended threshold of 0.85 [65], thereby reinforcing the distinctiveness of the measured constructs. Accordingly, the model is considered reliable and suitable for subsequent data analysis.

4.3. Hypothesis Test

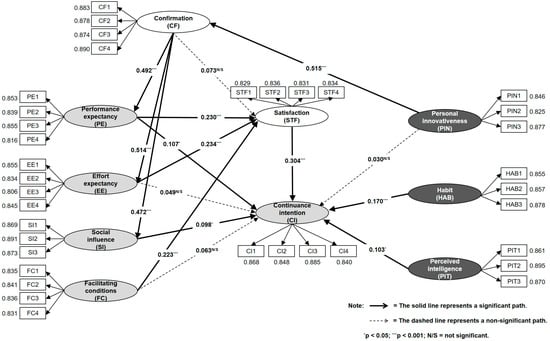

To assess the predictive capability of the composite model, this study analyzed the path coefficients along with the R2 and Q2 values. Detailed results are presented in Table 6. The R2 value reflects the proportion of variance in the endogenous constructs that is explained by the corresponding exogenous variables. For example, the R2 for continuance intention (CI) is 0.396, meaning that 39.6% of its variance is explained by its predictor variables. As a key indicator of model fit, the R2 values for satisfaction (STF) (0.333) and CI (0.396) both exceed the 26% threshold, suggesting that the model possesses considerable explanatory power [66]. Additionally, the Q2 values for all endogenous variables are greater than zero, confirming strong predictive relevance for future observations [25]. The study also examined the variance inflation factor (VIF) values. Results showed that all VIF values among variables were below 2 (see Table 6), which is under the commonly accepted threshold of 3 [67]. This indicates that the constructed model does not suffer from multicollinearity issues, and all path coefficients are stable and interpretable.

Table 6.

Outcomes of hypothesis verification.

The PLS-SEM approach was employed to examine how various factors influence STF and CI. As shown in Table 6, all proposed hypotheses were supported, except for H1d, H3b, H5b, and H7b.

Regarding the direct effects on STF, the findings show that performance expectancy (PE) (β = 0.230, p = 0.000), effort expectancy (EE) (β = 0.234, p = 0.000), and facilitating conditions (FC) (β = 0.223, p = 0.000) all have a significant positive impact. This suggests that fashion design students view AI-based integrated fashion design platforms (AIIFDP) as enhancing design efficiency, simplifying operational procedures, and offering adequate support, thereby increasing their overall satisfaction.

In terms of direct influences on CI, satisfaction (STF) (β = 0.304, p = 0.000) exerts the strongest positive effect. The study also finds that habit (HAB) (β = 0.170, p = 0.000) has a significant positive impact, suggesting that a higher level of automated behavioral tendency greatly enhances students’ continuance intention toward AIIFDP. Additionally, performance expectancy (PE) (β = 0.107, p < 0.05), perceived intelligence (PIT) (β = 0.103, p < 0.05), and social influence (SI) (β = 0.098, p < 0.05) also positively affect CI, although their influence is relatively weaker. In contrast, effort expectancy (EE) (β = 0.049, p > 0.05), facilitating conditions (FC) (β = 0.063, p > 0.05), and personal innovativeness (PIN) (β = 0.030, p > 0.05) show no statistically significant effect on CI. Meanwhile, PIN (β = 0.515, p = 0.000) exhibits a strong positive influence on confirmation (CF). CF also shows a positive correlation with PE, EE, and SI. The structural model results and the relationships among variables are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structural model results.

4.4. Mediating Effect Test

To examine the mediating effects within the model, this study employed bootstrapping with 5000 resamples and bias-corrected percentile confidence intervals. A mediation effect is considered significant if the confidence interval does not include zero [59].

The mediating role of STF was examined in the relationships between PE, EE, FC, and CI. Additionally, the study explored whether PE and EE mediate the relationship between CF and STF, and whether PIN indirectly influences CI through mediation pathways.

In the previous hypothesis testing, the direct effects of CF on STF, FC on CI, EE on CI, and PIN on CI were not fully supported. However, additional analysis (see Table 7) revealed two significant indirect paths: FC → STF → CI (95% CI [0.031, 0.123]), EE → STF → CI (95% CI [0.035, 0.124]). These findings suggest that FC and EE influence CI indirectly through STF. In addition, the confidence intervals for the two indirect paths—CF → PE → STF (95% CI [0.062, 0.169]) and CF → EE → STF (95% CI [0.067, 0.180])—do not include zero. This indicates that PE and EE serve as mediating factors linking CF to STF. We also found that the confidence intervals for the following four indirect paths were all above zero: PIN → CF → SI → CI (95% CI [0.006, 0.048]), PIN → CF → PE → CI (95% CI [0.003, 0.060]), PIN → CF → PE → STF → CI (95% CI [0.009, 0.033]), and PIN → CF → EE → STF → CI (95% CI [0.009, 0.035]). These findings suggest that PIN significantly influences CI through these indirect pathways. Specifically, in addition to working jointly with SI or PE as a mediator between PIN and CI, CF also collaborates with PE and STF, or with EE and STF, to enable the indirect effect of PIN on CI.

Table 7.

Mediating effect.

4.5. Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Analysis

4.5.1. ANN Modeling and Root Mean Square Error Test

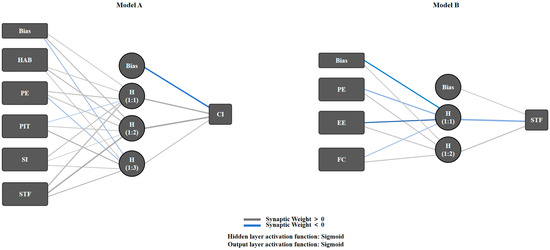

Based on the ANN model construction approach proposed in the Section 3, this study developed two models: Model A and Model B. Specifically, Model A includes one output neuron (CI) and five input neurons (HAB, PE, PIT, SI, STF); whereas Model B includes one output neuron (STF) and three input neurons (PE, EE, FC). Figure 4 presents the architecture of the ANN models.

Figure 4.

ANN models.

Subsequently, this study adopted a 10-fold cross-validation approach [57] to assess the predictive capability of Models A and B within the ANN framework, and the root mean square error (RMSE) was computed in line with established procedures [55,58]. In this procedure, the dataset was randomly split so that 90% of the data served as the training subset and the remaining 10% as the validation subset. This partitioning was repeated ten times to mitigate potential overfitting. The average RMSE values obtained for the training and validation stages were Model A (0.151 and 0.142) and Model B (0.149 and 0.136), respectively, as detailed in Table 8. Both ANN models exhibited satisfactory fit and high predictive accuracy, thus offering robust empirical support for the subsequent analyses.

Table 8.

RMSE value of ANN models.

4.5.2. Sensitivity Analysis in ANN and Comparative Analysis with SEM Results

To further explore the explanatory contributions of each independent variable, a sensitivity analysis was performed on both ANN models. This analysis quantified and compared the predictive strength of each input variable with respect to the target variable by calculating their normalized relative importance scores. In Model A, STF emerged as the most influential predictor of CI, with a normalized importance score set at 100.00%, serving as the benchmark. This was followed by HAB (59.09%), while PE (37.30%), SI (34.84%), and PIT (25.76%) occupied the third to fifth positions, respectively. In Model B, the relative importance scores for predicting STF indicated the following ranking: PE (94.00%) held the top position, followed by EE (88.46%) and FC (74.44%).

The normalized relative importance values derived from the ANN models were employed to assess the predictive influence of each independent variable. This metric offers a comparable interpretation to the standardized path coefficients used in PLS-SEM. Accordingly, this study conducted a cross-method comparison to evaluate the ranking consistency of predictor variables between the ANN results and those obtained through PLS-SEM [58]. As presented in Table 9, the rank orders of predictors in ANN Models A and B largely aligned with those identified in the PLS-SEM analysis. However, in Model A, the ranking of the “PIT → CI” and “SI → CI” paths showed slight divergence. This discrepancy may stem from the fact that ANN is capable of capturing complex, nonlinear, and non-compensatory relationships, which are not fully reflected in the linear and compensatory framework of PLS-SEM. In Model A, the standardized path coefficients for PIT and SI are extremely close (difference < 0.006), which may lead to divergent rankings between the two methods. Overall, the outcomes derived from the ANN analysis reinforce the reliability of the empirical results obtained through PLS-SEM. The integration of SEM and ANN methodologies in this study not only enhances the model’s explanatory capacity but also offers compelling empirical evidence supporting the overall robustness and validity of the proposed framework.

Table 9.

Comparative analysis of SEM-ANN results.

5. Discussion

5.1. Alignments and Divergences from Prior Research

This study found that heightened perceptions of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and facilitating conditions significantly enhanced Chinese fashion design students’ satisfaction with AI-based integrated fashion design platforms (AIIFDP). This result aligns with the findings of Teng et al. [42] in the field of digital technologies. It suggests that future research should further investigate how these factors influence individuals’ intentions to adopt GenAI platforms.

This study also confirmed the positive effects of performance expectancy and social influence on continuance intention, which is consistent with previous studies employing the UTAUT model [68]. This finding reinforces the dual-channel mechanism through which individual cognition and social evaluation shape user stickiness. However, this relationship has not been examined from the perspective of Chinese fashion design students in prior research. By introducing this refined perspective, the present study provides new insights for future investigations in related domains.

Previous studies [30,31] have confirmed that satisfaction plays a direct role in shaping continuance intention. The findings of this study support this conclusion and further demonstrate the mediating role of satisfaction in the relationships between performance expectancy, effort expectancy, facilitating conditions, and continuance intention. These results reinforce the critical importance of satisfaction in research on behavioral intention toward GenAI design platforms.

Although Al-Emran et al. [38] found that habit positively influences the intention to use AI chatbots, and Zhao et al. [36] demonstrated that perceived intelligence facilitates the adoption of digital technologies, these findings may not be directly transferable to Chinese fashion design students due to differences in the target population. Therefore, the current study emphasizes the positive effects of habit and perceived intelligence on continuance intention toward AIIFDP, providing theoretical support for future research in this context.

This study further confirmed that confirmation is positively associated with performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence, consistent with the findings reported by Yu et al. [16]. However, their research did not explore the impact of personal innovativeness on confirmation. Addressing this gap, the present study highlights the positive effect of individual trait variables on confirmation.

Additionally, although previous studies [22] identified effort expectancy and facilitating conditions as significant predictors of designers’ continuance intention toward AI platforms, and Twum et al. [37] empirically confirmed the positive correlation between personal innovativeness and usage intention, the present study did not observe significant effects of effort expectancy, facilitating conditions, or personal innovativeness on continuance intention. These discrepancies suggest opportunities for further investigation into the influence of these variables. The following section provides an in-depth interpretation of the key findings from this study.

Moreover, the findings reveal a multi-level mechanism in which cognitive, emotional, habitual, and external factors jointly influence continuance behavior. This enriches the theoretical understanding of adopting AIIFDP in fashion design education and also offers practical strategies for curriculum development and the optimization of AIIFDP, which will be further discussed in the Section 5.5.

5.2. Direct Effects of Predictors on Satisfaction and Continuance Intention

This study found that confirmation significantly enhances Chinese fashion design students’ positive perceptions of AIIFDP in terms of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence. These findings affirm the predictive validity of the ECM model in explaining relevant mechanisms, suggesting that when Chinese fashion design students’ actual experiences with AIIFDP closely align with their expectations, they tend to perceive the platform as more useful, easier to use, and more socially endorsed. Therefore, the internal cognitive updating mechanism shapes Chinese fashion design students’ subjective judgments regarding the effectiveness and social evaluation of AIIFDP as an AI-supported fashion design information system. This finding holds significant theoretical value for sustaining long-term engagement in human–AI collaboration systems.

Satisfaction, as a core predictive variable within the “user–information system” interaction framework, integrates Chinese fashion design students’ multidimensional experience cues with AIIFDP into a unified emotional feedback response. This study found that performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and facilitating conditions each contribute positively to shaping satisfaction. The significant effect of performance expectancy suggests that when AIIFDP offers clearly defined functional modules, its user-friendly design enhances students’ experience, thereby fostering a more favorable attitude [14,16]. Additionally, the ease of operating AIIFDP, along with adequate hardware support and instructional guidance [42], is also identified as a key factor that may influence satisfaction.

The findings of this study identify satisfaction as the strongest determinant of continuance intention, extending the conclusions of earlier research [32]. When the actual performance of AIIFDP and the external environmental support meet or exceed Chinese fashion design students’ expectations, they are more likely to experience positive emotions [8] and form favorable evaluations—both of which significantly enhance their intention to continue using the platform.

This study also found that the perceived functional value of AIIFDP as a fashion design support system (performance expectancy) and the social diffusion mechanisms (social influence) each exert a notable positive effect on Chinese fashion design students’ intention to continue using AIIFDP. The notable impact of performance expectancy underscores that students expect AIIFDP to continually enhance the quality of content generation [8]. When students believe that using AIIFDP can not only improve their efficiency but also result in higher-quality designs, such positive perceptions will encourage their continued use of the platform. Of course, as a relatively new design technology, AIIFDP still involves certain uncertainties regarding its functionality and implementation. Consequently, Chinese fashion design students may adopt a cautious attitude and rely on instructors’ opinions to guide their decisions [22]. Moreover, peer recommendations also play an influential role in shaping students’ behavior. When more teachers and classmates begin to endorse the use of AIIFDP, and when students are motivated to stay abreast of technological trends and remain professionally competitive, the impact of social influence becomes even more pronounced.

In addition, the finding that habit significantly influences continuance intention further reinforces the view that habits serve as a key driver of behavior [38]. Once Chinese fashion design students have developed the habit of using GenAI platforms for idea generation, effect enhancement, and other forms of design assistance, their engagement with such platforms becomes more automatic. When presented with AIIFDP, which offers more specific and expanded features, they are likely to try it with minimal hesitation and continue using it.

Finally, this study found that perceived intelligence—students’ perception of the intelligence level demonstrated by the AIIFDP system during task interactions—affects their judgment of whether the platform’s performance meets their expectations. The “human-like” attributes of AI also influence Chinese fashion design students’ willingness to embrace the technology, confirming previous research findings [36,69] in the context of AIIFDP. Therefore, intelligence perception is not only an evaluation of AIIFDP’s technical capabilities but also a critical component of the human–AI compatibility system.

5.3. Indirect Effects of Predictors on Satisfaction and Continuance Intention

The results of this study reveal that confirmation does not exert a significant direct effect on satisfaction, which contradicts the conclusion established by the classic ECM, where confirmation is shown to directly influence satisfaction [14]. However, mediation analysis indicates that confirmation significantly enhances Chinese fashion design students’ satisfaction indirectly through its effects on performance expectancy and effort expectancy. This suggests that students may place greater emphasis on the actual performance of the platform in supporting design tasks [70]. Specifically, they care about whether AIIFDP enables efficient task completion, offers intuitive functionality, and provides a user-friendly experience. Therefore, their satisfaction is not solely determined by the degree to which the platform aligns with their initial expectations, but is instead co-constructed through a multi-path, multi-stage interactive perception process.

While effort expectancy does not exhibit a significant direct effect on continuance intention, it still has a notable indirect impact through the mediating role of satisfaction. This suggests that although the operational logic of AIIFDP is relatively easy to grasp, a certain learning curve and operational complexity remain. As a result, Chinese fashion design students are more inclined to assess the actual value of AIIFDP based on their usage experience and the level of satisfaction it brings, which ultimately influences their decision to continue using the platform. In this feedback loop, the ease of use and operational convenience of AIIFDP as an intelligent design support system may translate into emotional resonance, thereby affecting continuance intention.

The study also found that facilitating conditions influence continuance intention indirectly through satisfaction. This may be because, in most cases, external support such as adequate hardware and network infrastructure does not directly alter Chinese fashion design students’ willingness to use the platform. Proficient use of AIIFDP often requires personal exploration and repeated practice [71]. As students gradually master the platform and gain a sense of fulfillment from its use, their satisfaction increases, which in turn reinforces their continuance intention. Additionally, the study revealed that personal innovativeness influences continuance intention indirectly through confirmation and subsequent cognitive factors—namely, social influence, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and satisfaction. Highly innovative fashion design students tend to develop positive expectations upon first encountering AIIFDP and show a greater willingness to engage with it [16]. However, their willingness to continue using the platform still depends on whether AIIFDP meets their expectations. Specifically, students will first make a judgment based on the alignment between their expected outcomes of AIIFDP and their personal expectations. Then, through the actual performance experience during use, they will form a perception of satisfaction, which in turn influences their intention to continue using this intelligent design support system. This multi-stage information-processing chain reinforces the view that continuance intention is shaped by layered interactions between the individual and the information system.

Additionally, this study’s finding of a positive correlation between confirmation and social influence also indicates that when Chinese fashion design students perceive AIIFDP’s performance to meet or even exceed their expectations, they are more likely to accept positive evaluations and recommendations from teachers and classmates [72]. This also reveals the pathway through which individual-level cognitive appraisal influences social evaluation factors. This further strengthens their identification with AIIFDP.

The significant mediating path results point to a multi-level behavioral generation mechanism. Chinese fashion design students’ continuance intention toward AIIFDP depends not only on performance expectancy, perceived intelligence, habit, and social influence, but also on their satisfaction with actual use and the “chain” effects of multiple perceptual factors. This also emphasizes the need to view the adoption of design support systems as a dynamic and adaptive process.

5.4. Theoretical Contribution

This study offers four significant contributions to enhancing the understanding of Chinese fashion design students’ behavior and technology acceptance, and to advancing the theoretical frontier of GenAI adoption research in design education.

First, this study addresses a previously overlooked vertical domain—namely, behavioral intention toward specialized integrated GenAI design platforms. Moreover, it adopts the perspective of fashion design students, diverging from the traditional research approach that fails to differentiate between students and industry professionals. Thus, this study clearly defines the boundary of its target population, enabling the construction of more context-sensitive behavioral models for researching continuance intention toward AIIFDP. In turn, it clearly identifies the key determinants influencing Chinese fashion design students’ satisfaction with AIIFDP and their intention to continue using it.