Peptide Profiling and Biological Activities of 12-Month Ripened Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Extraction of Water-Soluble Peptides from 12-Month Ripened Parmigiano Reggiano (PR) Samples and Determination of the Peptides Concentration

2.3. Biological Activities Analysis

2.3.1. Antioxidant Activity

2.3.2. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity

2.3.3. Dipeptidyl-Peptidase-IV Inhibitory Activity

2.4. Peptide Profiling by Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography/High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC/HR-MS)

2.5. Identification of Bioactive Peptides

2.6. Quantification of VPP and IPP by Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

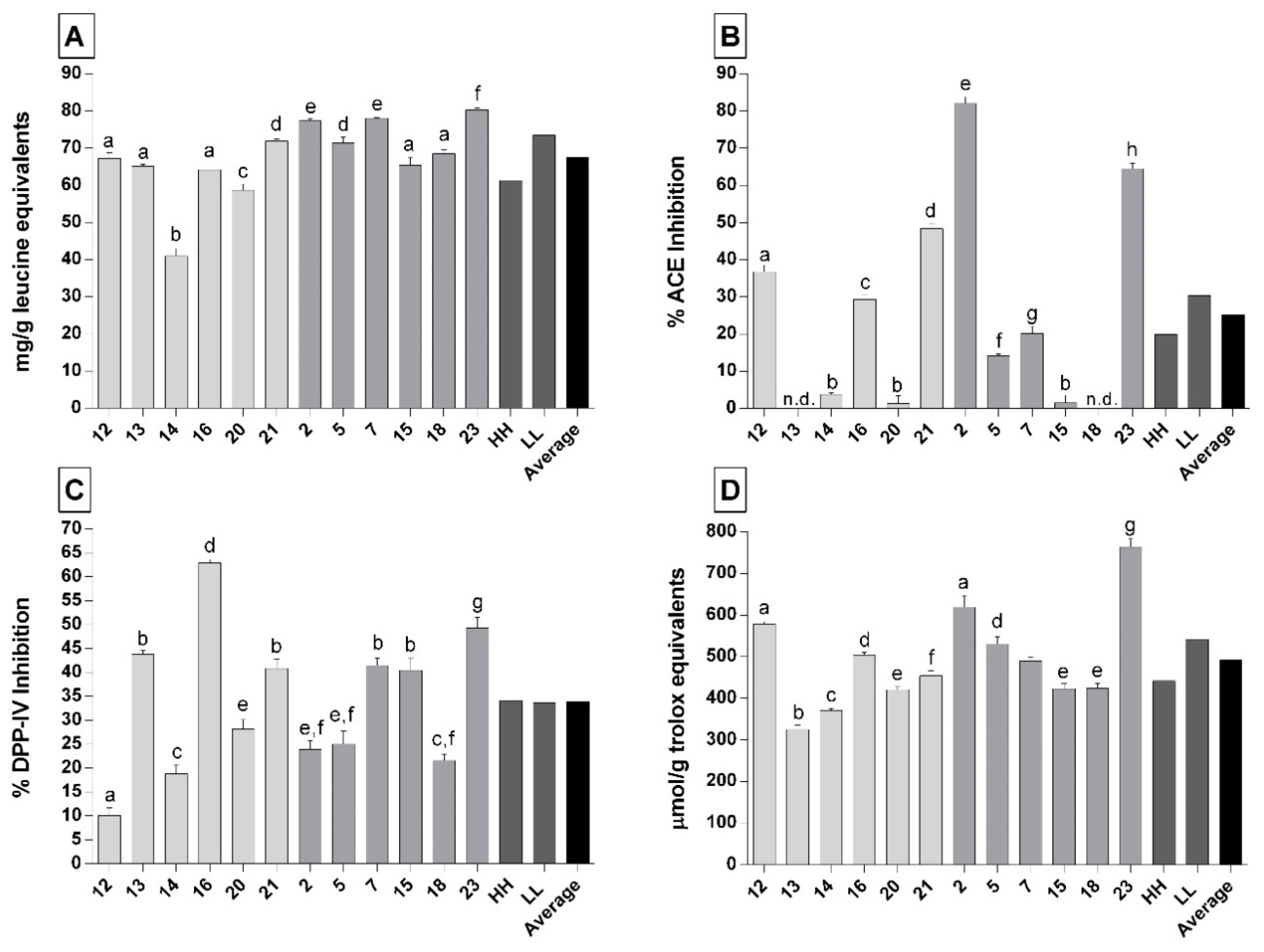

3.1. Total Peptides Quantification in the Peptide Fractions of 12-Month Ripened Parmigiano Reggiano Samples

3.2. Biological Activities of the Peptide Fractions of 12-Month Ripened Parmigiano Reggiano Samples

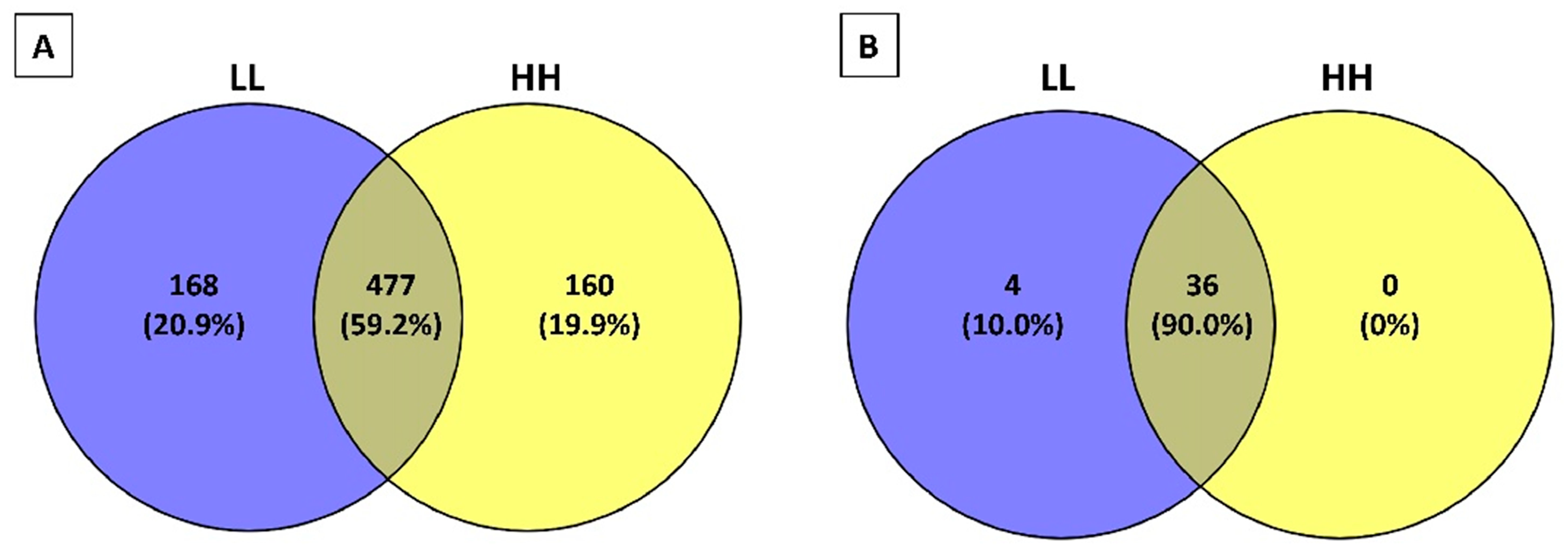

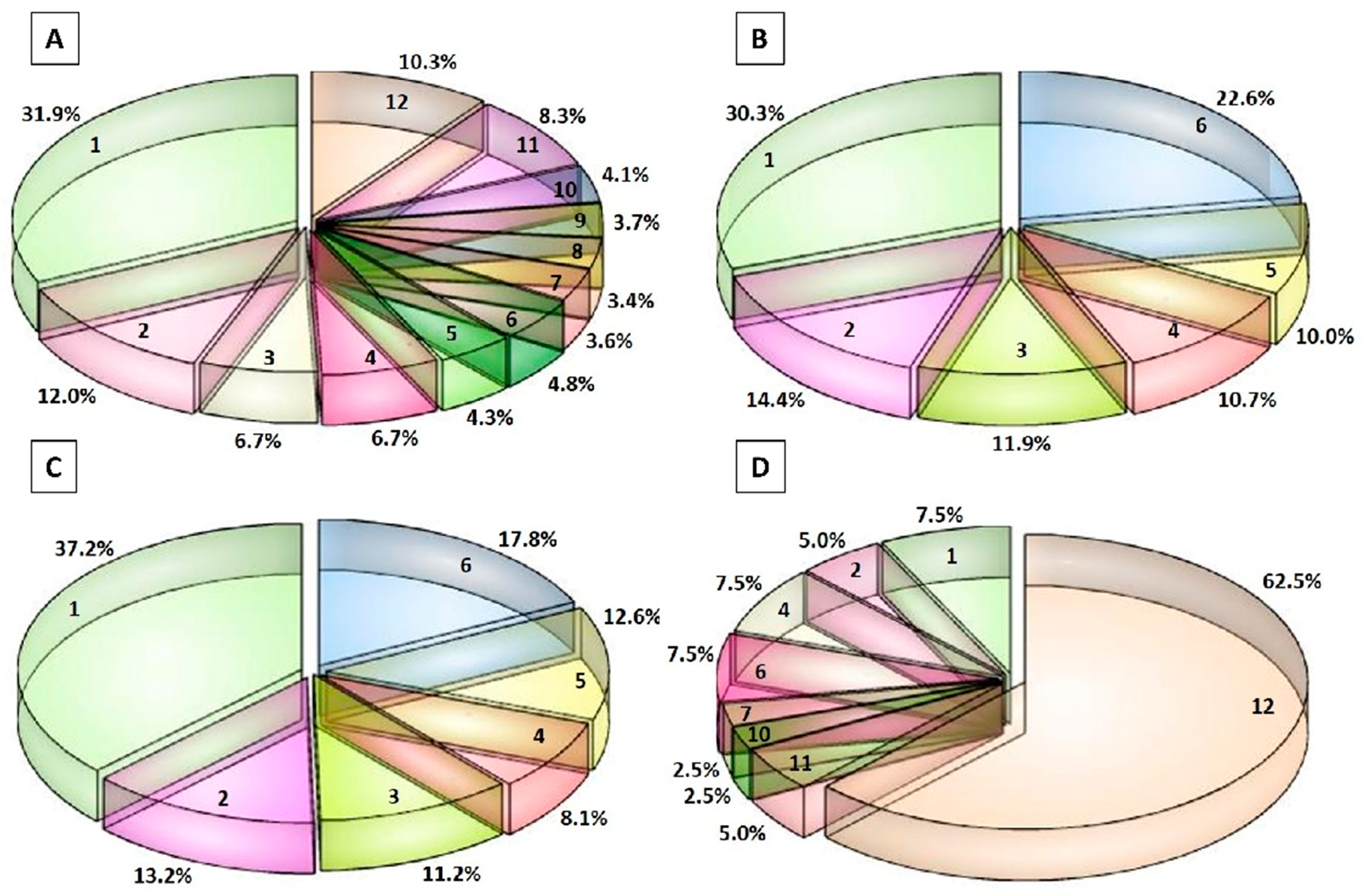

3.3. Peptidomic Profile of the Peptide Fractions of 12-Month Ripened Parmigiano Reggiano Samples

3.4. Bioactive Peptides in 12-Month Ripened Parmigiano Reggiano Peptide Fractions and Quantification of VPP and IPP

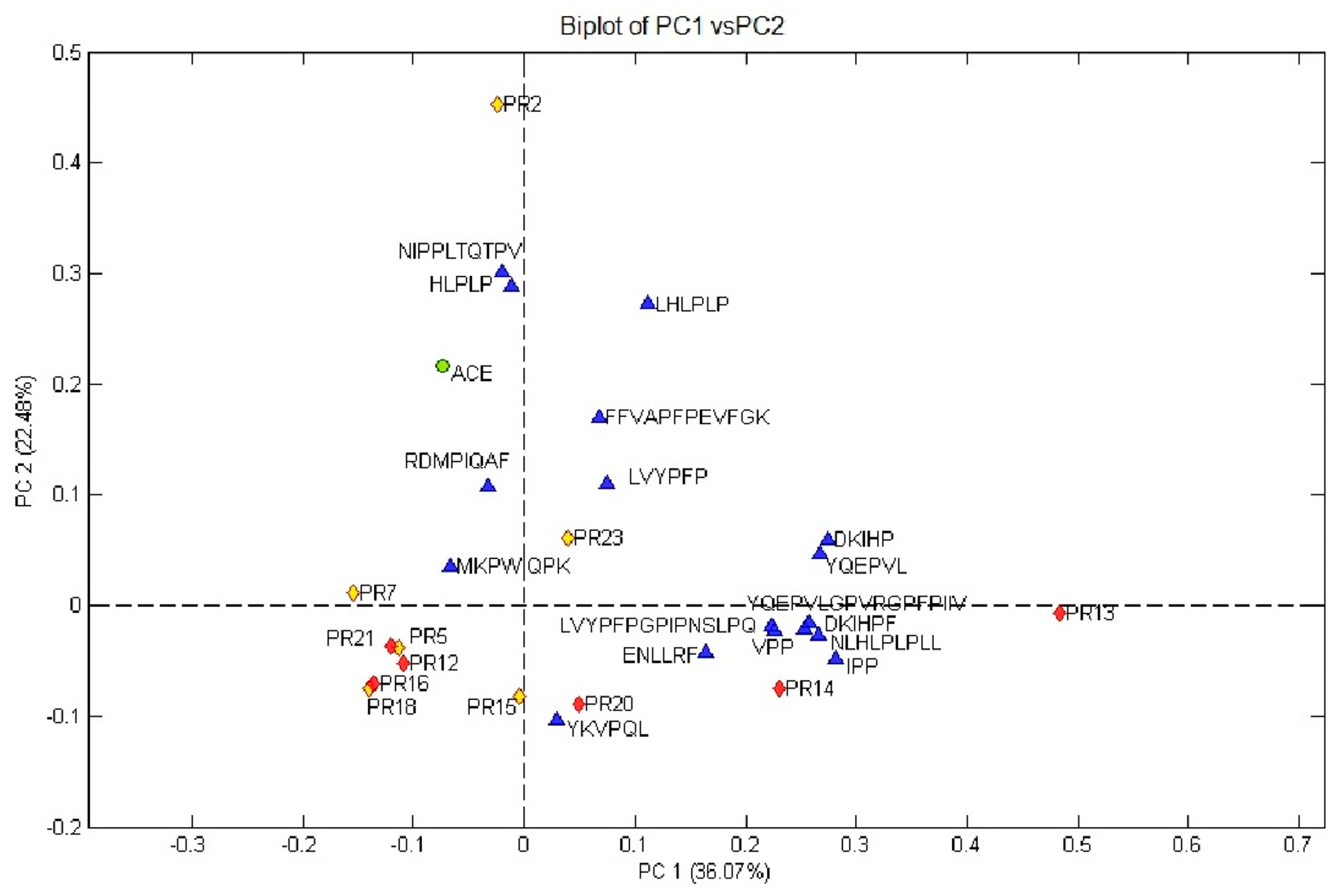

3.5. Relationship between the ACE-Inhibitory Activity and ACE-Inhibitory Peptides Profile in 12-Month Ripened Parmigiano Reggiano Peptide Fractions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Godos, J.; Tieri, M.; Ghelfi, F.; Titta, L.; Marventano, S.; Lafranconi, A.; Gambera, A.; Alonzo, E.; Sciacca, S.; Buscemi, S.; et al. Dairy foods and health: An umbrella review of observational studies. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 71, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Givens, D.I.; Astrup, A.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Goossens, G.H.; Kratz, M.; Marette, A.; Pijl, H.; Soedamah-Muthu, S.S. The impact of dairy products in the development of type 2 diabetes: Where does the evidence stand in 2019? Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagliazucchi, D.; Martini, S.; Solieri, L. Bioprospecting for bioactive peptide production by lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented dairy food. Fermentation 2019, 5, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summer, A.; Formaggioni, P.; Franceschi, P.; Di Frangia, F.; Righi, F.; Malacarne, M. Cheese as functional food: The example of Parmigiano-Reggiano and Grana Padano. Food Technol. Biotech. 2017, 55, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sforza, S.; Galaverna, G.; Neviani, E.; Pinelli, C.; Dossena, A.; Marchelli, M. Study of the oligopeptide fraction in Grana Padano and Parmigiano-Reggiano cheeses by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 10, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sforza, S.; Cavatorta, V.; Lambertini, F.; Galaverna, G.; Dossena, A.; Marchelli, R. Cheese peptidomics: A detailed study on the evolution of the oligopeptide fraction in Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese from curd to 24 months of aging. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 3514–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, R.; Bütikofer, U.; Egger, C.; Portmann, R.; Walther, B.; Wechsler, D. ACE-inhibitory activity and ACE-inhibiting peptides in different cheese varieties. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2010, 90, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Expósito, I.; Miralles, B.; Amigo, L.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Health effects of cheese components with a focus on bioactive peptides. In Fermented Foods in Health and Disease Prevention; Frias, J., Martinez-Villaluenga, C., Peñas, E., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MU, USA, 2017; pp. 239–273. [Google Scholar]

- Solieri, L.; Bianchi, A.; Giudici, P. Inventory of non-starter lactic acid bacteria from ripened Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese as assessed by a culture dependent multiphasic approach. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 35, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottari, B.; Levante, A.; Neviani, E.; Gatti, M. How the fewest become the greatest. L. casei’s impact on long ripened cheeses. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliazucchi, D.; Baldaccini, A.; Martini, S.; Bianchi, A.; Pizzamiglio, V.; Solieri, L. Cultivable non-starter lactobacilli from ripened Parmigiano Reggiano cheeses with different salt content and their potential to release anti-hypertensive peptides. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 330, 108688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, M.; Mente, A.; Yusuf, S. Sodium intake and cardiovascular health. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, F.M.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Wu, J.H.Y.; Appel, L.J.; Creager, M.A.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Miller, M.; Rimm, E.B.; Rudel, L.L.; Robinson, J.C.; et al. Dietary fats and cardiovascular disease: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 136, e1–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD-FAO. Chapter 7. Dairy and dairy products. In OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2018–2027; OECE Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, C.M.; Kelly, P.M.; Wilkinson, M.G.; Guinee, T.P. Effect of fat and salt reduction on the changes in the concentrations of free amino acids and free fatty acids in Cheddar-style cheeses during maturation. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2017, 59, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.M.; Kelly, P.M.; Wilkinson, M.G.; Guinee, T.P. Effect of salt and fat reduction on proteolysis, rheology: And cooking properties of Cheddar cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2016, 56, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, K.K.; Rattray, F.P.; Bredie, W.L.P.; Høier, E.; Ardö, Y. Physicochemical and sensory characterization of Cheddar cheese with variable NaCl levels and equal moisture content. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 1953–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, V.V. Low fat cheese technology. Int. Dairy J. 2001, 11, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinee, T.P. Protein in cheese products: Structure-function relationships. In Advanced Dairy Chemistry, 4th ed.; McSweeney, P.L.H., O’Mahony, S.A., Eds.; Springer Science: New York, NY, USA; Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 347–415. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, M.G.; Guinee, T.P.; O’Callaghan, D.M.; Fox, P.F. Autolysis and proteolysis in different strains of starter bacteria during Cheddar cheese ripening. J. Dairy Res. 1994, 61, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Y.F.; McSweeney, P.L.H.; Wilkinson, M.G. Evidence for a relationship between autolysis of starter bacteria and lipolysis in Cheddar cheese. J. Dairy Res. 2003, 70, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenelon, M.A.; O’Connor, P.; Guinee, T.P. The effect of fat content on the microbiology and proteolysis in Cheddar cheese during ripening. J. Dairy Sci. 2000, 83, 2173–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidona, F.; Bernardi, M.; Francolino, S.; Ghiglietti, R.; Hogenboom, J.A.; Locci, F.; Zambrini, V.; Carminati, D.; Giraffa, G. The impact of sodium chloride reduction on Grana-type cheese production and quality. J. Dairy Res. 2019, 86, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler-Nissen, J. Determination of the degree of hydrolysis of food protein hydrolysates by trinitrobenzensulfonic acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1979, 27, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Bio. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutella, G.S.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Solieri, L. Survival and bioactivities of selected probiotic lactobacilli in yogurt fermentation and cold storage: New insight for developing a bi-functional dairy food. Food Microbiol. 2016, 60, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagliazucchi, D.; Martini, S.; Shamsia, S.; Helal, A.; Conte, A. Biological activity and peptidomic profile of in vitro digested cow, camel, goat and sheep milk. Int. Dairy J. 2018, 81, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, S.; Conte, A.; Tagliazucchi, D. Effect of ripening and in vitro digestion on the evolution and fate of bioactive peptides in Parmigiano Reggiano cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2020, 105, 104668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.D.; Beverly, R.L.; Qu, Y.; Dallas, D.C. Milk bioactive peptide database: A comprehensive database of milk protein-derived bioactive peptides and novel visualization. Food Chem. 2017, 232, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, A.; Salvi, L.; Coruzzi, P.; Salvi, P.; Parati, G. Sodium intake and hypertension. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, M.A.; Petersen, K.S.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Saturated fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: Replacements for saturated fat to reduce cardiovascular risk. Healthcare 2017, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangallo, D.; Kraková, L.; Puškárová, A.; Šoltys, K.; Bučková, M.; Koreňová, J.; Budiš, J.; Kuchta, T. Transcription activity of lactic acid bacterial proteolysis-related genes during cheese maturation. Food Microbiol. 2019, 82, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, C.L.; Bodyfelt, F.W.; Wyatt, C.J.; McDaniel, M.R. Reduction of sodium chloride in cheddar cheese: Effect on sensory, microbiological, and chemical properties. J. Dairy Sci. 1988, 71, 2010–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Fox, P.F.; McSweeney, P.L.H. Effect of salt-in-moisture on proteolysis in Cheddar-type cheese. Milchwissenschaft 1996, 51, 498–501. [Google Scholar]

- Rulikowska, A.; Kilcawley, K.N.; Doolan, I.A.; Alonso-Gomez, M.; Nongonierma, A.B.; Hannon, J.A.; Wilkinson, M.G. The impact of reduced sodium chloride content on Cheddar cheese quality. Int. Dairy J. 2013, 28, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, D.P.; Araújo, F.D.S.; Eberlin, M.N.; Gigante, M.L. Reduction of 25% salt in Prato cheese does not affect proteolysis and sensory acceptance. Int. Dairy J. 2017, 75, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piuri, M.; Sanchez-Rivas, C.; Ruzal, S.M. Adaptation to high salt in Lactobacillus: Role of peptides and proteolytic enzymes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, P.F. Significance of indigenous enzymes in milk and dairy products. In Handbook of Food Enzymology; Whitaker, J.R., Voragen, A.G.J., Wong, D.W.S., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Summer, A.; Franceschi, P.; Formaggioni, P.; Malacarne, M. Characteristics of raw milk produced by free-stall or tie-stall cattle herds in the Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese production area. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2014, 94, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summer, A.; Franceschi, P.; Formaggioni, P.; Malacarne, M. Influence of milk somatic cell content on Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese yield. J. Dairy Res. 2015, 82, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraffa, G.; Mucchetti, G.; Neviani, E. Interactions among thermophilic lacto-bacilli during growth in cheese whey. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1996, 80, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraffa, G.; Neviani, E. Different Lactobacillus helveticus strain populations dominate during Grana Padano cheesemaking. Food Microbiol. 1999, 16, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, A.; Maistro, L.D.; De Dea, P.; Gatti, M.; Giraffa, G.; Neviani, E. A polyphasic approach to highlight genotypic and phenotypic diversities of Lactobacillus helveticus strains isolated from dairy starter cultures and cheeses. J. Dairy Res. 2002, 69, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottari, B.; Santarelli, M.; Neviani, E.; Gatti, M. Natural whey starter for Parmigiano Reggiano: Culture-independent approach. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 108, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, R.; Nanni, M.; Iorizo, M.; Sorrentino, A.; Sorrentino, E.; Chiavari, C.; Grazia, L. Microbiological characteristics of Parmigiano Reggiano cheese during the cheesemaking and the first months of the ripening. Le Lait 2000, 80, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dea Lindner, J.; Bernini, V.; De Lorentiis, A.; Pecorari, A.; Neviani, E.; Gatti, M. Parmigiano Reggiano cheese: Evolution of cultivable and total lactic micro-flora and peptidase activities during manufacture and ripening. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2008, 88, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bütikofer, U.; Meyer, J.; Sieber, R.; Wechsler, D. Quantification of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibiting tripeptides Val-Pro-Pro and Ile-Pro-Pro in hard, semi-hard and soft cheeses. Int. Dairy J. 2007, 17, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uenishi, H.; Kabuki, T.; Seto, Y.; Serizawa, A.; Nakajima, H. Isolation and identification of casein-derived dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 (DPP-4)-inhibitory peptide LPQNIPPL from gouda-type cheese and its effect on plasma glucose in rats. Int. Dairy J. 2012, 22, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Mann, B.; Kumar, R.; Sangwan, R.B. Antioxidant capacity of Cheddar cheeses at different stages of ripening. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2009, 62, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottesini, C.; Paolella, S.; Lambertini, F.; Galaverna, G.; Tedeschi, T.; Dossena, A.; Marchelli, R.; Sforza, S. Antioxidant capacity of water soluble extracts from Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 64, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleminger, G.; Ragones, H.; Merin, U.; Silanikove, N.; Leitner, G. Low molecular mass peptides generated by hydrolysis of casein impair rennet coagulation of milk. Int. Dairy J. 2013, 30, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozo, J.; Strahinic, I.; Dalgalarrondo, M.; Chobert, J.M.; Haertlé, T.; Topisirovic, C. Comparative analysis of β-casein proteolysis by PrtP proteinase from Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei BGHN14, PrtR proteinase from Lactobacillus rhamnosus BGT10 and PrtH proteinase from Lactobacillus helveticus BGRA43. Int. Dairy J. 2011, 21, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solieri, L.; De Vero, L.; Tagliazucchi, D. Peptidomic study of casein proteolysis in bovine milk by Lactobacillus casei PRA205 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus PRA331. Int. Dairy J. 2018, 85, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juillard, V.; Laan, H.; Kunji, E.R.S.; Jeronimus-Stratingh, C.M.; Bruins, A.P.; Konings, W.N. The extracellular PI-type proteinase of Lactococcus lactis hydrolyzes β-casein into more than one hundred different oligopeptides. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 3472–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeno, M.; Yamamoto, N.; Takano, T. Identification of antihypertensive peptides from casein hydrolysate produced by a proteinase from Lactobacillus helveticus CP790. J. Dairy Sci. 1996, 73, 1316–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunda, P.B.; Benavente, F.; Catalá-Clariana, S.; Giménez, E.; Barbosa, J.; Sanz-Nebot, V. Identification of bioactive peptides in a functional yogurt by micro liquid chromatography time-of-flight mass spectrometry assisted by retention time prediction. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 1229, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basiricò, L.; Catalani, E.; Morera, P.; Cattaneo, S.; Stuknyte, M.; Bernabucci, U.; De Noni, I.; Nardone, A. Release of angiotensin converting enzyme-inhibitor peptides during in vitro gastrointestinal digestion of Parmigiano-Reggiano PDO cheese and their absorption through an in vitro model of intestinal epithelium. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 7595–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuknyte, M.; Cattaneo, S.; Masotti, F.; De Noni, I. Occurrence and fate of ACE-inhibitor peptides in cheeses and in their digestates following in vitro static gastrointestinal digestion. Food Chem. 2015, 168, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel, M.; Recio, I.; Ramos, M.; Delgado, M.A.; Aleixandre, M.A. Antihypertensive effect of peptides obtained from Enterococcus faecalis-fermented milk in rats. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 33523359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiros, A.; Ramos, M.; Muguerza, B.; Delgado, M.A.; Miguel, M.; Aleixandre, A.; Recio, I. Identification of novel antihypertensive peptides in milk fermented with Enterococcus faecalis. Int. Dairy J. 2007, 17, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, M.C.; Razaname, A.; Mutter, M.; Juillerat, M.A. Identification of angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides derived from sodium caseinate hydrolysates produced by Lactobacillus helveticus NCC 2765. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 6923–6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkor, O.N.; Henriksson, A.; Singh, T.K.; Vasiljevic, T.; Shah, N.P. ACE-inhibitory activity of probiotic yoghurt. Int. Dairy J. 2007, 17, 1321–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele, T.; Stressler, T.; Kranz, B.; Fischer, L. Bioactive peptides generated in an enzyme membrane reactor using Bacillus lentus alkaline peptidase. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013, 236, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.; Gómez-Ruiz, J.A.; Recio, I.; Aleixandre, A. Changes in arterial blood pressure after single oral administration of milk-casein-derived peptides in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, 1422–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Fogacci, F.; Colletti, A. Potential role of bioactive peptides in prevention and treatment of chronic diseases: A narrative review. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1378–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, H.; Pihlanto-Leppäla, A.; Rantamäki, P.; Tupasela, T. Impact of processing on bioactive proteins and peptides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1998, 9, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ruiz, J.Á.; Ramos, M.; Recio, I. Identification and formation of angiotensin converting enzyme-inhibitory peptides in Manchego cheese by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1054, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.; Bütikofer, U.; Walther, B.; Wechsler, D.; Sieber, R. Changes in angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and concentrations of the tripeptides Val-Pro-Pro and Ile-Pro-Pro during ripening of different Swiss cheese varieties. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sequence b | Fragment | Activity c | LL Samples | HH Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-casein | ||||

| RELEELNVPGEIVESLSSSEESITR | 1–25 | Caseinophosphopeptide | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR14 |

| TEDELQDKIHPF | 41–52 | Anti-microbial | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| DKIHP | 47–51 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 113 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| DKIHPF | 47–52 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 257 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| LVYPFP | 58–63 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 132 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| LVYPFPGPIPNSLPQ | 58–72 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 18 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| VYPFPGPIPN | 59–68 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 325 µmol/L) Antihypertensive (−7.0 mmHg) Antioxidant | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| YPFPGPIPN | 60–68 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 15 µmol/L) Antihypertensive (−7.0 mmHg) DPP-IV-inhibition (IC50 = 670 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| PGPIPN | 63–68 | Immunomodulatory Anti-cancer | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| NIPPLTQTPV | 73–82 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 173 µmol/L) | PR2 | n.d. |

| TQTPVVVPPFLQPE | 78–91 | Antioxidant | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| PVVVPPFLQPE | 81–91 | Anti-microbial | PR2 | n.d. |

| VKEAMAPK | 98–105 | Anti-microbial Antioxidant | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| YPVEPF | 114–119 | Opioid DPP-IV-inhibition (IC50 = 125 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| NLHLPLPLL | 132–140 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 15 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| LHLPLP | 133–138 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 4 µmol/L) Antihypertensive (−25.3 mmHg) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| HLPLP | 134–138 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 41 µmol/L) Antihypertensive (−23.5 mmHg) | PR2 | n.d. |

| KVLPVPQ | 159–175 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 1000 µmol/L) Antihypertensive (−31.5 mmHg) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| RDMPIQAF | 183–190 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 209 µmol/L) | PR2, PR7, PR15, PR23 | n.d. |

| YQEPVLGPVRGPFPI | 193–207 | Anti-microbial | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| YQEPVLGPVRGPFPIIV | 193–209 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 101 µmol/L) Anti-microbial Antioxidant Immunomodulatory | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| QEPVLGPVRGPFPIIV | 194–209 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 600 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| VRGPFPIIV | 201–209 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 600 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| αS1-casein | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 | |||

| RPKHPIKHQGLPQEVLNENLLRF | 1–23 | Anti-microbial | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| ENLLRF | 18–23 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 82 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| FFVAPFPEVFGK | 23–34 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 52 µmol/L) Antihypertensive (−34.0 mmHg) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| HIQKEDVPSERYLGYLEQLLRLK | 80–102 | Anti-microbial | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR13, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| HIQKEDVPSERYLGYLEQLLRLKKYK | 80–102 | Anti-microbial | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR13, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| YLGYLEQLLR | 91–101 | Anxiolytic | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| LRLKKYKVPQL | 99–109 | Anti-microbial | PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13 |

| YKVPQL | 104–109 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 22 µmol/L) Antihypertensive (−12.5 mmHg) | PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| αS2-casein | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 | |||

| IVLNPWDQVK | 104–113 | Anti-microbial | PR2 | PR14 |

| VPITPT | 117–140 | DPP-IV-inhibition (IC50 = 130 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| TVYQHQKAMKPWIQPKTKVIPYVRYL | 182–207 | Anti-microbial | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| VYQHQKAMKPWIQPKTKVIPYVRYL | 183–207 | Anti-microbial | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| AMKPWIQPK | 189–197 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 600 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| MKPWIQPK | 190–197 | ACE-inhibition (IC50 = 300 µmol/L) | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| WIQPKTKVIPYVRYL | 193–207 | Anti-microbial | PR15, PR18 | PR13, PR14 |

| TKVIPYVRYL | 198–207 | Anti-microbial | PR2, PR5, PR7, PR15, PR18, PR23 | PR12, PR13, PR14, PR16, PR20, PR21 |

| Sequence * | PR12 mg/kg | PR13 mg/kg | PR14 mg/kg | PR16 mg/kg | PR20 mg/kg | PR21 mg/kg | Average mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPP | 3.41 ± 0.18 a | 16.36 ± 0.96 b | 6.57 ± 0.31 c | 3.64 ± 0.11 a | 10.49 ± 0.74 d | 4.34 ± 0.34 e | 7.47 |

| IPP | 0.62 ± 0.04 a | 2.76 ± 0.17 b | 1.64 ± 0.09 c | 0.65 ± 0.02 a | 0.99 ± 0.05 d | 0.63 ± 0.02 a | 1.22 |

| Sequence * | PR2 mg/kg | PR5 mg/kg | PR7 mg/kg | PR15 mg/kg | PR18 mg/kg | PR23 mg/kg | Average mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPP | 4.84 ± 0.21 a | 5.11 ± 0.22 a | 5.67 ± 0.29 b | 7.90 ± 0.33 c | 3.27 ± 0.10 d | 6.82 ± 0.31 e | 5.60 |

| IPP | 0.61 ± 0.04 a | 0.86 ± 0.07 b | 1.01 ± 0.08 b | 1.50 ± 0.09 c | 0.70 ± 0.04 a | 1.31 ± 0.09 c | 1.00 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Solieri, L.; Baldaccini, A.; Martini, S.; Bianchi, A.; Pizzamiglio, V.; Tagliazucchi, D. Peptide Profiling and Biological Activities of 12-Month Ripened Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese. Biology 2020, 9, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9070170

Solieri L, Baldaccini A, Martini S, Bianchi A, Pizzamiglio V, Tagliazucchi D. Peptide Profiling and Biological Activities of 12-Month Ripened Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese. Biology. 2020; 9(7):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9070170

Chicago/Turabian StyleSolieri, Lisa, Andrea Baldaccini, Serena Martini, Aldo Bianchi, Valentina Pizzamiglio, and Davide Tagliazucchi. 2020. "Peptide Profiling and Biological Activities of 12-Month Ripened Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese" Biology 9, no. 7: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9070170

APA StyleSolieri, L., Baldaccini, A., Martini, S., Bianchi, A., Pizzamiglio, V., & Tagliazucchi, D. (2020). Peptide Profiling and Biological Activities of 12-Month Ripened Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese. Biology, 9(7), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9070170