The Water Content Drives the Susceptibility of the Lichen Evernia prunastri and the Moss Brachythecium sp. to High Ozone Concentrations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental

2.2. Physiological Parameters

2.2.1. Chlorophyll Content

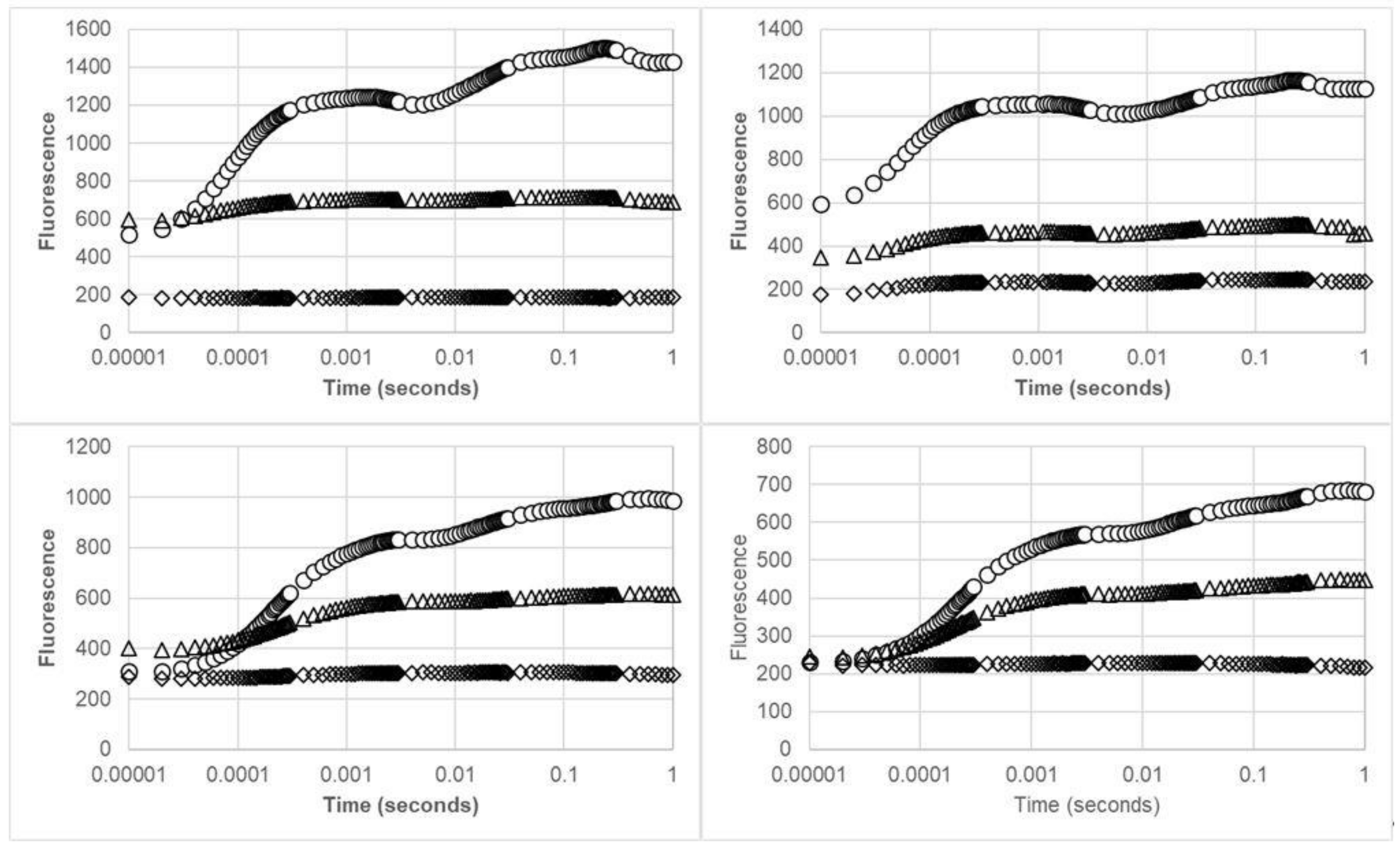

2.2.2. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Analysis

2.2.3. Total Antioxidant Power

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilkinson, S.; Mills, G.; Illidge, R.; Davies, W.J. How is ozone pollution reducing our food supply? J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 63, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santurtún, A.; Gonzalez-Hidalgo, J.C.; Sanchez-Lorenzo, A.; Zarrabeitia, M.T. Surface ozone concentration trends and its relationship with weather types in Spain (2001–2010). Atmospheric Environ. 2015, 101, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaro, L.; Palma, A.; Salvatori, E.; Basile, A.; Maresca, V.; Karam, E.A.; Manes, F. Functional indicators of response mechanisms to nitrogen deposition, ozone, and their interaction in two Mediterranean tree species. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0185836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Lemonnier, P.; Wedow, J.M. The influence of rising tropospheric carbon dioxide and ozone on plant productivity. Plant Boil. 2019, 22, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimis, P.L.; Scheidegger, C.; Wolseley, P.A. Monitoring with Lichens–Monitoring Lichens; Kluwer Academic Publ.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzini, G.; Landi, U.; Loppi, S.; Nali, C. Lichen distribution and biondicator tobacco plants give discordant response: A case study from Italy. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2003, 82, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gombert, S.; Asta, J.; Seaward, M. Lichens and tobacco plants as complementary biomonitors of air pollution in the Grenoble area (Isère, southeast France). Ecol. Indic. 2006, 6, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nali, C.; Balducci, E.; Frati, L.; Paoli, L.; Loppi, S.; Lorenzini, G. Integrated biomonitoring of air quality with plants and lichens: A case study on ambient ozone from central Italy. Chemosphere 2007, 67, 2169–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzi, S.; Davies, L.; Power, S.A.; Tretiach, M. Why lichens are bad biomonitors of ozone pollution? Ecol. Indic. 2013, 34, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddell, J.; Padgett, P.; Nash, T. Physiological responses of lichens to factorial fumigations with nitric acid and ozone. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 170, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, E.; Bertuzzi, S.; Carniel, F.C.; Lorenzini, G.; Nali, C.; Tretiach, M. Ozone tolerance in lichens: A possible explanation from biochemical to physiological level using Flavoparmelia caperata as test organism. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 1514–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iii, T.H.N.; Sigal, L.L. Gross Photosynthetic Response of Lichens to Short-Term Ozone Fumigations. Bryologist 1979, 82, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosentreter, R.; Ahmadjian, V. Effect of Ozone on the Lichen Cladonia arbuscula and the Trebouxia Phycobiont of Cladina stellaris. Bryologist 1977, 80, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.H.; Smirnofff, N. Observations on the Effect of Ozone on Cladonia Rangiformis. Lichenologist 1978, 10, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannini, A.; Paoli, L.; Ceccarelli, S.; Sorbo, S.; Basile, A.; Carginale, V.; Nali, C.; Lorenzini, G.; Pica, M.; Loppi, S. Physiological and ultrastructural effects of acute ozone fumigation in the lichen Xanthoria parietina: The role of parietin and hydration state. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 25, 8104–8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, L.; Foot, J.P.; Caporn, S.; Lee, J.A. Responses of four Sphagnum species to acute ozone fumigation. J. Bryol. 1996, 19, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, L.; Foot, J.P.; Caporn, S.J.M.; Lee, J.A. The effects of long-term elevated ozone concentrations on the growth and photosynthesis of Sphagnum recurvum and Polytrichum commune. New Phytol. 1996, 134, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, R.; Martikainen, P.J.; Silvola, J.; Holopainen, T. Ozone effects on Sphagnum mosses, carbon dioxide exchange and methane emission in boreal peatland microcosms. Sci. Total. Environ. 2002, 289, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanosz, G.; Smith, V.; Bruck, R. Effect of ozone on growth of mosses on disturbed forest soil. Environ. Pollut. 1990, 63, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash III, T.H.; Egan, R.S. The biology of lichens and bryophytes. In Lichens, Briophytes and Air Quality; Bibl. Lichenol.: Berlin/Stuttgart, Germany, 1988; Volume 30, pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vannini, A.; Paoli, L.; Russo, A.; Loppi, S. Contribution of submicronic (PM1) and coarse (PM>1) particulate matter deposition to the heavy metal load of lichens transplanted along a busy road. Chemosphere 2019, 231, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussotti, F.; Strasser, R.J.; Schaub, M. Photosynthetic behavior of woody species under high ozone exposure probed with the JIP-test: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 147, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Diao, E.; Shen, X.; Ma, W.; Ji, N.; Dong, H. Ozone-Induced Changes in Phenols and Antioxidant Capacities of Peanut Skins. J. Food Process. Eng. 2014, 37, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Statistical Methodol.) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 13 February 2012).

- Heath, R.L. Possible mechanisms for the inhibition of photosynthesis by ozone. Photosynth. Res. 1994, 39, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Gunten, U. Ozonation of drinking water: Part I. Oxidation kinetics and product formation. Water Res. 2003, 37, 1443–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraudner, M.; Wiese, C.; Van Camp, W.; Moeder, W.; Inzé, D.; Langebartels, C.; Jr, H.S. Ozone-induced oxidative burst in the ozone biomonitor plant, tobacco Bel W3. Plant J. 1998, 16, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, T.G.A.; Kulle, D.; Pannewitz, S.; Sancho, L.; Schroeter, B. UV-A protection in mosses growing in continental Antarctica. Polar Boil. 2005, 28, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titus, J.E.; Wagner, D.J.; Stephens, M.D. Contrasting Water Relations of Photosynthesis for Two Sphagnum Mosses. Ecology 1983, 64, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, O.L.; Green, T.G.A. Lichens show that fungi can acclimate their respiration to seasonal changes in temperature. Oecologia 2004, 142, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannewitz, S.; Green, T.A.; Maysek, K.; Schlensog, M.; Seppelt, R.; Sancho, L.; Türk, R.; Schroeter, B. Photosynthetic responses of three common mosses from continental Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 2005, 17, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winner, W.E.; Bewley, J.D. Photosynthesis and respiration of feather mosses fumigated at different hydration levels with SO2. Can. J. Bot. 1983, 61, 1456–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rürk, R.; Wirth, V.; Lange, O.L. CO2-Gaswechsel-Untersuchungen zur SO2-Resistenz von Flechten. Oecologia 1974, 15, 33–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieboer, E.; Tomassini, F.D.; Puckett, K.J.; Richardson, D.H.S. A model for the relationship between gaseous and aqueous concentrations of sulphur dioxide in lichen exposure studies. New Phytol. 1977, 79, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, A.; Nali, C.; Ciompi, S.; Lorenzini, G.; Soldatini, G.F.; Ranieri, A. Ozone exposure affects photosynthesis of pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo) plants. New Phytol. 2001, 152, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelgar, W.P.; Green, T.G.A.; Wilkins, A.L. Carbon dioxide exchange in lichens: Resistances to CO2 uptake at different thallus water contents. New Phytol. 1981, 88, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger, C.; Schroeter, B. Effects of ozone fumigation on epiphytic macrolichens: Ultrastructure, CO2 gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence. Environ. Pollut. 1995, 88, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.J.; Nash, T.H. Effect of ozone on gross photosynthesis of lichens. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1983, 23, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimis, P.L. The Lichens of Italy. A Second Annotated Catalogue; EUT: Trieste, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, B.; Gillespie, T.J.; Puckett, K.J. Uptake of gaseous sulphur dioxide by the lichen Cladina rangiferina. Can. J. Bot. 1985, 63, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, M.; Jürgens, S.-R.; Brinkmann, M.; Herminghaus, S. Surface Hydrophobicity Causes SO2 Tolerance in Lichens. Ann. Bot. 2007, 101, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, L.; Pisani, T.; Munzi, S.; Gaggi, C.; Loppi, S. Influence of sun irradiance and water availability on lichen photosynthetic pigments during a Mediterranean summer. Biologia 2010, 65, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B.; Schoettle, A.W.; Raba, R.M.; Amundson, R.G. Response of Soybean to Low Concentrations of Ozone: I. Reductions in Leaf and Whole Plant Net Photosynthesis and Leaf Chlorophyll Content. J. Environ. Qual. 1986, 15, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelius, A.S.; Näslund, K.; Carlsson, A.S.; Pleijel, H.; Selldén, G. Exposure of spring wheat (Triticum aestivum) to ozone in open-top chambers. Effects on acyl lipid composition and chlorophyll content of flag leaves. New Phytol. 1995, 131, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudson, L.L.; Tibbitts, T.W.; Edwards, G.E. Measurement of Ozone Injury by Determination of Leaf Chlorophyll Concentration. Plant Physiol. 1977, 60, 606–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, E. PSII photochemistry is the primary target of oxidative stress imposed by ozone in Tilia americana. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatayud, A.; Temple, P.; Barreno, E. Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Emission, Xanthophyll Cycle Activity, and Net Photosynthetic Rate Responses to Ozone in Some Foliose and Fruticose Lichen Species. Photosynthetica 2000, 38, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussotti, F.; Desotgiu, R.; Cascio, C.; Pollastrini, M.; Gravano, E.; Gerosa, G.; Marzuoli, R.; Nali, C.; Lorenzini, G.; Salvatori, E.; et al. Ozone stress in woody plants assessed with chlorophyll a fluorescence. A critical reassessment of existing data. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2011, 73, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köllner, B.; Krause, G.H.M. Effects of Two Different Ozone Exposure Regimes on Chlorophyll and Sucrose Content of Leaves and Yield Parameters of Sugar Beet (Beta Vulgaris L.) and Rape (Brassica Napus L.). Water Air Soil Pollut. 2003, 144, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.; Agrawal, M. Assessment of competitive ability of two Indian wheat cultivars under ambient O3 at different developmental stages. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 21, 1039–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, M.S.; Pell, E.J. Decline of Activity and Quantity of Ribulose Bisphosphate Carboxylase/Oxygenase and Net Photosynthesis in Ozone-Treated Potato Foliage. Plant Physiol. 1989, 91, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualini, S.; Antonielli, M.; Ederli, L.; Piccioni, C.; Loreto, F. Ozone uptake and its effect on photosynthetic parameters of two tobacco cultivars with contrasting ozone sensitivity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2002, 40, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, V.; Pinelli, P.; Pasqualini, S.; Reale, L.; Ferranti, F.; Loreto, F. Isoprene decreases the concentration of nitric oxide in leaves exposed to elevated ozone. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, U.; Vidaver, W.; Runeckles, V.C.; Rosén, P. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Assay for Ozone Injury in Intact Plants. Plant Physiol. 1978, 61, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heber, U.; Azarkovich, M.; Shuvalov, V. Activation of mechanisms of photoprotection by desiccation and by light: Poikilohydric photoautotrophs*. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 2745–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausladen, A.; Madamanchi, N.R.; Fellows, S.; Alscher, R.G.; Amundson, R.G. Seasonal changes in antioxidants in red spruce as affected by ozone. New Phytol. 1990, 115, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.S.; Alscher, R.G.; McCune, D. Response of Photosynthesis and Cellular Antioxidants to Ozone in Populus Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1991, 96, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, J.; Weigel, H.; Wegner, U.; Jäger, H. Response of cellular antioxidants to ozone in wheat flag leaves at different stages of plant development. Environ. Pollut. 1994, 84, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, W.K.; Ali, A.; Forney, C. Effects of ozone on major antioxidants and microbial populations of fresh-cut papaya. Postharvest Boil. Technol. 2014, 89, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviranta, N.M.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R.; Oksanen, E.; Karjalainen, R.O. Leaf phenolic compounds in red clover (Trifolium pratense L.) induced by exposure to moderately elevated ozone. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J.; Jentsch, A.; Beierkuhnlein, C.; Kreyling, J. Ecological stress memory and cross stress tolerance in plants in the face of climate extremes. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 94, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | LED | LEW | LRD | LRW |

| Chl | 0.85 ± 0.19 A | 0.00B* | 0.89 ± 0.47 A | 0.00B* |

| FV/FM | 0.21 ± 0.09 A | 0.00 B* | 0.19 ± 0.14 A | 0.00B* |

| ARA | 1.51 ± 0.09 Aa | 1.11 ± 0.08 Ba | 1.19 ± 0.02 Ab | 0.83 ± 0.01 Bb |

| MED | MEW | MRD | MRW | |

| Chl | 0.96 ± 0.13 A | 0.48 ± 0.17 Ba | 0.73 ± 0.27 | 0.73 ± 0.18 b |

| FV/FM | 0.35 ± 0.11 Aa | 0.00B* | 0.70 ± 0.14 Ab | 0.00B* |

| ARA | 1.16 ± 0.20 a | 1.30 ± 0.11a | 1.04 ± 0.05 Ab | 1.17 ± 0.01 Bb |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vannini, A.; Canali, G.; Pica, M.; Nali, C.; Loppi, S. The Water Content Drives the Susceptibility of the Lichen Evernia prunastri and the Moss Brachythecium sp. to High Ozone Concentrations. Biology 2020, 9, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9050090

Vannini A, Canali G, Pica M, Nali C, Loppi S. The Water Content Drives the Susceptibility of the Lichen Evernia prunastri and the Moss Brachythecium sp. to High Ozone Concentrations. Biology. 2020; 9(5):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9050090

Chicago/Turabian StyleVannini, Andrea, Giulia Canali, Mario Pica, Cristina Nali, and Stefano Loppi. 2020. "The Water Content Drives the Susceptibility of the Lichen Evernia prunastri and the Moss Brachythecium sp. to High Ozone Concentrations" Biology 9, no. 5: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9050090

APA StyleVannini, A., Canali, G., Pica, M., Nali, C., & Loppi, S. (2020). The Water Content Drives the Susceptibility of the Lichen Evernia prunastri and the Moss Brachythecium sp. to High Ozone Concentrations. Biology, 9(5), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9050090