1. Introduction

Polyphagous thrips are globally important agricultural pests widely distributed across tropical and subtropical regions. Their minute body size and high reproductive capacity enable infestation across diverse crops [

1,

2]. Thrips possess piercing-sucking mouthparts and initiate feeding by rasping plant surfaces before inserting their stylets to extract cellular contents. This feeding behavior induces tissue necrosis, leaf deformation, and fruit developmental abnormalities, ultimately compromising both crop yield and quality [

3,

4]. Furthermore, several species function as competent vectors of plant viruses such as tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), impatiens necrotic spot virus (INSV), and groundnut ringspot virus (GRSV), thereby posing a dual threat through both direct feeding damage and virus transmission [

5,

6]. Together, these traits render thrips a persistent threat to the biosecurity and sustainability of modern agricultural production.

In protected cropping systems, thrips exhibit continuous year-round occurrence and rapid generational turnover [

7,

8]. Their capacity for parthenogenetic reproduction, rapid evolution of insecticide resistance, and pronounced cryptic behavior further contributes to their persistence in high-value horticultural crops [

8,

9]. In southern coastal regions of China, the expansion of protected cultivation and intensified cross-regional trade have markedly reshaped the regional distribution patterns and dominant species composition of thrips populations [

10,

11]. Currently, the flower thrips

Frankliniella intonsa (Trybom, 1895) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), the bean thrips

Megalurothrips usitatus (Bagnall, 1913), and the Hawaiian flower thrips

Thrips hawaiiensis (Morgan, 1913) dominate local agricultural systems in Fujian Province [

12,

13], whereas the invasive western flower thrips

Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande, 1895), originally absent from most provinces in China, has in recent years rapidly expanded its distribution range, progressively establishing stable populations and exhibiting strong competitive displacement of native species, thereby emerging as a dominant pest in greenhouse-based protected cropping systems [

14].

As a result, agricultural ecosystems increasingly exhibit the coexistence of multiple thrips species, with interspecific resource partitioning and competitive interactions that may influence population dynamics [

15,

16]. Accurate identification and real-time monitoring of dominant thrips populations are therefore fundamental for elucidating population succession and coexistence mechanisms and serve as essential prerequisites for precision pest management [

17,

18]. However, the high morphological similarity among species, fragility of specimens, and frequent cooccurrence substantially limit the accuracy and efficiency of traditional morphological approaches, particularly under field monitoring conditions [

19,

20]. Although mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (

COI) markers have been widely applied in molecular identification, barcoding approaches rely on sequencing platforms and thus fall short of supporting rapid, field-adaptable diagnostics [

21]. Despite the broad adoption for amplifying conserved mitochondrial barcoding loci, universal

COI primers are not intended for direct species discrimination at the PCR level. When applied to samples containing closely related or co-occurring thrips species, universal primers may yield mixed amplification products, which require subsequent sequencing for accurate species assignment and thus limit their suitability for rapid, field-adaptable identification without sequencing [

22]. The limitations are further amplified by the practical constraints of current molecular workflows, which usually depend on specialized laboratory equipment and controlled laboratory conditions. These include thermocyclers, centrifuges, and gel-based detection systems, as well as multi-step DNA purification procedure, that involve multiple handling and transfer steps, even in commonly used column-based extraction workflows, thereby limiting the applicability to low-input analyses from individual insects under field conditions [

23]. Compounding this challenge, crude lysates from individual insects may contain co-extracted substances that interfere with downstream PCR amplification, thereby reducing amplification efficiency and reliability rather than the efficiency of DNA extraction itself [

24,

25].

In summary, the frequent coexistence of multiple thrips species and dynamic shifts in species dominance underscores the pressing need for a molecular species identification framework that integrates species-level resolution, operational simplicity, and field-adaptable applicability. To address this challenge, the present study focused on thrips species most frequently encountered in local agricultural systems, together with a globally invasive species F. occidentalis, and performed a systematic assessment of mitochondrial COI polymorphisms to pinpoint hypervariable regions conducive to species-specific primer development. Concurrently, six DNA extraction protocols were evaluated and optimized to establish a short-turnaround, species-specific molecular identification that reconciles species-level resolution with field-compatible applicability and is more time-efficient than sequencing-based barcoding. Departing from conventional COI barcoding approaches restricted to laboratory-based sequencing, this study combines polymorphism-guided primer design with a PBS-based DNA extraction strategy for single-insect samples that requires no column-based purification steps, establishing a modular identification framework oriented toward laboratory and field applications. Such integration effectively bridges the gap between laboratory molecular assays and field-adaptable surveillance and lays a molecular foundation for seamless incorporation of isothermal amplification and visual nucleic acid detection platforms, including CRISPR/Cas12a-based assays, to advance intelligent pest monitoring and to accelerate the transition toward portable, data-driven molecular species identification frameworks in smart agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Materials and Rearing Maintenance

Four thrips species used in this study were F. intonsa, F. occidentalis, M. usitatus, and T. hawaiiensis. Among them, F. intonsa, M. usitatus, and T. hawaiiensis are dominant native species commonly found in agricultural systems throughout Fujian Province, while F. occidentalis has rapidly spread in China. The F. occidentalis laboratory strain was established in 2018 from a starter population provided by the Institute of Biotechnology and Germplasm Resources, Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Field-derived strains of F. intonsa (2021, collected on cucumber, Cucumis sativus L., 1753), M. usitatus (2021, collected on cowpea, Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp., 1843), and T. hawaiiensis (2017, collected on sweet osmanthus, Osmanthus fragrans (Thunb.) Lour., 1790) were established independently from populations sampled in Minhou, Fuzhou, Fujian, China. All four species have been maintained under laboratory conditions for multiple years. Each species has been reared independently under strict biosecurity protocols to prevent cross-contamination and to ensure stable laboratory populations. Species identity was regularly verified using morphological characteristics and mitochondrial COI barcoding. All species were maintained in a controlled-environment chamber (CRX-350B, Fujian Zhongyouling Technology Co., Ltd., Fuzhou, China) set at 22 ± 1 °C, 75 ± 5% RH, and a 16:8 h light:dark (L:D) photoperiod. Strain health and developmental synchrony were routinely monitored throughout rearing.

Rearing followed a previously described system [

26], which was further optimized in this study to enhance egg collection efficiency and minimize contamination risk. For

F. intonsa,

F. occidentalis, and

T. hawaiiensis, adults were maintained and allowed to oviposit in custom frustum-shaped polypropylene cages (Cage A; top diameter 8 cm, bottom diameter 11 cm, height 8 cm). The cage top was covered with breathable mesh, and the bottom was sealed with Parafilm

® M (Bemis Company, Inc., Sheboygan Falls, WI, USA) and positioned above a water-filled tray to maintain membrane moisture while preventing direct water contact. Approximately 300 healthy adults (mixed sexes) were introduced into each cage (≥3 cages per species per batch), and germinated broad beans (

Vicia faba) were supplied as food and replaced every 48 h to prevent microbial contamination. Females oviposited through the Parafilm into the membrane–water interface. Eggs were gently collected by rinsing the membrane three times with 10 mL of distilled water per rinse and subsequently vacuum-filtered using a SHZ-D(III) water-circulating vacuum pump (Zhengzhou Greatwall, Zhengzhou, China) onto black Whatman No. 1 filter paper (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) or black cotton cloth to enhance visibility. By contrast,

M. usitatus showed poor adaptation to the Parafilm-based oviposition setup; therefore, germinated broad beans were placed directly inside the cage as the oviposition substrate. After 48 h, beans containing

M. usitatus eggs and eggs of the other species collected from the Parafilm membranes were each transferred to their respective rectangular rearing cages (Cage B; 12 × 8 × 6 cm; fine-mesh sides) for hatching and nymphal development. A moistened filter paper sheet (Whatman No. 1, Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) was placed on the cage bottom to maintain humidity and provide a pupation substrate, and both food and filter paper were replaced every 2 days. All thrips strains were maintained under the same controlled rearing conditions described above. Empty rearing cages and associated tools were sprayed with 70% ethanol and disinfected with UV light for 30 min before introducing the next generation. Developmental progress was monitored daily, and temperature and humidity were recorded using the built-in sensors of the environmental chamber to ensure stable rearing conditions. Individuals were collected at the designated developmental stages for subsequent analyses.

2.2. Morphometric Analysis and COI Reference Sequence Generation in Four Thrips Species

To ensure consistency across replicates and to eliminate variability caused by sexual dimorphism, ten adult females of each species were collected from laboratory-reared populations at 1–3 days post-eclosion. All individuals were fully sclerotized, morphologically intact, and free from visible deformities. Because pronounced sexual dimorphism in body size and external morphology exists between males and females, only females were examined for morphometric analysis to eliminate sex-related variability and ensure consistent and comparable measurements. This restriction was applied exclusively to the morphological measurements. Individual specimens were positioned at the center of a microscope slide for stereomicroscopic imaging. The wings were symmetrically aligned along the body axis in the same focal plane to minimize distortion caused by improper posture. Stereomicroscope imaging was performed using ZSA402 stereomicroscope (Chongqing Optec Instrument Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China). All images were calibrated using embedded 200 μm scale bars, and morphometric measurements were performed in millimeters (mm) using the S-EYE 2.0 image analysis system integrated with the stereomicroscope (Chongqing Optec Instrument Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China). All measurements were recorded to two decimal places.

All individuals used in this study were directly sampled from four well-established laboratory strains whose identity had been routinely verified through morphological examination and mitochondrial COI barcoding. At the start of the experimental workflow, species identity was further confirmed based on full-length mitochondrial COI sequence information prior to subsequent method development. For molecular characterization and generation of high-quality COI reference sequences, genomic DNA was extracted from 50 adult individuals randomly selected from laboratory-maintained strains, including both females and males, using a conventional buffer-based DNA extraction method (CB-Std), which consists of Tris–EDTA–NaCl buffer preparation, SDS-mediated lysis, and alcohol precipitation. Full-length mitochondrial COI fragments (approximately 1500 bp) from these individuals were then amplified and sequenced to generate high-quality templates for primer design. The extraction buffer consisted of 1.461 g NaCl (Solarbio, Beijing, China), 5 mL of 1 M Tris-HCl (Solarbio, Beijing, China), and 5 mL of 0.5 M EDTA (Solarbio, Beijing, China), which was adjusted to pH 8.0 and brought to a final volume of 50 mL with sterile ultrapure water (Milli-Q system; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA). The buffer was stored at 4 °C. Each specimen was homogenized in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube using a sterile micro-pestle. For lysis, 500 μL of extraction buffer and 100 μL of 10% SDS (Solarbio, Beijing, China) were added to each tube, followed by incubation at 56 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, 200 μL of 2 M potassium acetate (Solarbio, Beijing, China) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and mixed with an equal volume of pre-chilled isopropanol (Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China; AR grade) to precipitate DNA. The resulting DNA pellet was air-dried, resuspended in 20 μL of sterile ultrapure water (Milli-Q system; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA), and stored at −20 °C until use.

PCR amplification was carried out in a 25 μL reaction volume containing 12.5 μL of 2× Taq PCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), 1 μL each of forward and reverse primers (10 μM), 1 μL of genomic DNA template, and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 25 μL. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 58 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were verified by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel, and target fragments were excised and purified using a Gel Extraction Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA). Purified PCR fragments were ligated into the pJET1.2 vector using the CloneJET PCR Cloning Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and transformed into

Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Transformed cells were plated on LB agar supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 12–16 h. Positive colonies were inoculated into LB broth containing ampicillin and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm for 6 h prior to plasmid extraction. Inserts were confirmed by PCR using pJET1.2 universal primers, and the products were validated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Sequencing was carried out in both directions by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Raw sequence reads were assembled and manually curated using SnapGene (version 6.2.1; GSL Biotech LLC, San Diego, CA, USA;

https://www.snapgene.com/), generating high-quality

COI reference sequences for the four target thrips species. These verified sequences were subsequently used as templates for species-specific primer design and downstream analyses.

2.3. Sequence Alignment and Species-Specific Primer Design

Based on the obtained

COI sequences, multiple sequence alignment and characterization were performed using MEGA software (version 12.0; Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA). Given that

COI is a protein-coding gene with a conserved reading frame, sequence alignment was primarily inspected and refined manually. Nucleotide composition (A%, T%, G%, and C%) and GC content were calculated to assess base composition bias and sequence complexity across the four thrips species. Pairwise genetic distances were estimated under the

p-distance model, with missing data treated using pairwise deletion, resulting in a genetic distance matrix among species. To identify species-specific regions, the aligned

COI sequences were further visualized and manually examined using SnapGene (version 6.2.1; GSL Biotech LLC, San Diego, CA, USA;

https://www.snapgene.com/) to locate variable nucleotide sites. Regions exhibiting high polymorphism were annotated as potential targets for primer design.

During primer design, highly conserved regions were excluded to avoid reduced discriminatory power. Candidate primers were selected from the most variable

COI segments, with priority given to those containing at least one species-specific nucleotide at the 3′ terminus. Design principles were as follows: (1) targeting regions with the highest nucleotide variability; (2) maintaining amplicon lengths between 600 and 800 bp; (3) avoiding regions with high homology to non-target species; and (4) minimizing the formation of hairpins, dimers, or self-complementarity. All primers were designed using Primer Premier (version 6.0; PREMIER Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA, USA;

https://www.premierbiosoft.com/) and further checked in SnapGene (version 6.2.1; GSL Biotech LLC, San Diego, CA, USA;

https://www.snapgene.com/) to confirm complete matching to the intended target region and to exclude predicted secondary structures in the primers. Final primer sequences are provided in

Table S1.

2.4. Validation of Primer Specificity and Performance

Amplification efficiency and species specificity were evaluated by performing PCR assays using genomic DNA from the four thrips species under the same thermal cycling program as COI amplification. Amplicons were resolved on 1% agarose gels to verify the presence of the expected species-specific band. Each primer pair was tested against its cognate target and all non-target species. Primer pairs yielding a single, distinct band in the target species and no amplification in non-targets were considered specific and selected for further validation. Primer performance under mixed-template backgrounds was assessed using two mock DNA communities to simulate interspecific mixtures. The first mixture consisted of genomic DNA from F. intonsa, F. occidentalis, M. usitatus, and T. hawaiiensis, with each species contributing an equal amount to a total of 50 ng DNA per reaction. The second mixture contained only the three non-target species, with the total DNA amount likewise adjusted to 50 ng per reaction, excluding the target species for a given primer pair. Reactions were run under the same conditions as single species assays. Successful species discrimination was defined as amplification only in mixtures containing the target species, with no bands in target-absent mixtures.

2.5. Short-Turnaround DNA Extraction and Single Thrips Adult PCR Detection

To evaluate short-turnaround DNA extraction strategies suitable for single-insect diagnostics under resource-limited conditions, six extraction methods were systematically compared using individual adult thrips. These included a modified conventional protocol (CB-Std) and five short-turnaround alternatives designed to reduce procedural complexity while maintaining compatibility with downstream PCR.

The CB-Std method (

Section 2.2) served as the reference protocol and involved SDS-based chemical lysis, potassium acetate precipitation, and DNA resuspension. For single-adult processing, the total reaction volume was reduced from 500 μL to 20 μL with proportional adjustment of reagents. The five short-turnaround extraction methods were classified according to buffer composition and lysis strategy. Three detergent-free methods employed sterile distilled water (SDW; Milli-Q system; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; ABKBio, Xiamen Aibikang Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Xiamen, China), or 20 mM EDTA (Solarbio, Beijing, China) as lysis media. For these methods, individual thrips were homogenized in 20 μL of the respective buffer and subjected to brief heat lysis at 98 °C for 2 min, followed by cooling to room temperature. Importantly, the PBS-based protocol did not include SDS or any other detergents, and the resulting lysates were used directly as PCR templates without further purification. In contrast, a simplified detergent-assisted protocol (CB-SDS) utilized a reduced-concentration lysis buffer containing 0.2% SDS to evaluate the effect of mild detergent inclusion on DNA release and amplification efficiency. A nitrocellulose membrane contact transfer (NCM) method was also evaluated. In this approach, individual thrips were directly pressed onto nitrocellulose membranes (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and air-dried at room temperature. Prior to PCR, membrane fragments (approximately 0.5 × 0.5 cm) bearing the thrips contact trace were excised and transferred into 20 μL of sterile water (Milli-Q system; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA). The thrips contact trace was defined as residual biological material transferred from the insect body surface during physical contact, including cuticular fragments, cellular debris, and trace amounts of internal tissue or hemolymph sufficient to serve as a DNA template. Samples were heated at 98 °C for 2 min to release DNA and then cooled to room temperature before PCR.

DNA concentration and purity were measured using a NanoDrop microvolume spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For each extraction method, ten biological replicates were tested per thrips species, resulting in a total of 240 PCR amplification reactions. Amplification performance was assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis to compare band clarity, specificity, and PCR compatibility across extraction methods.

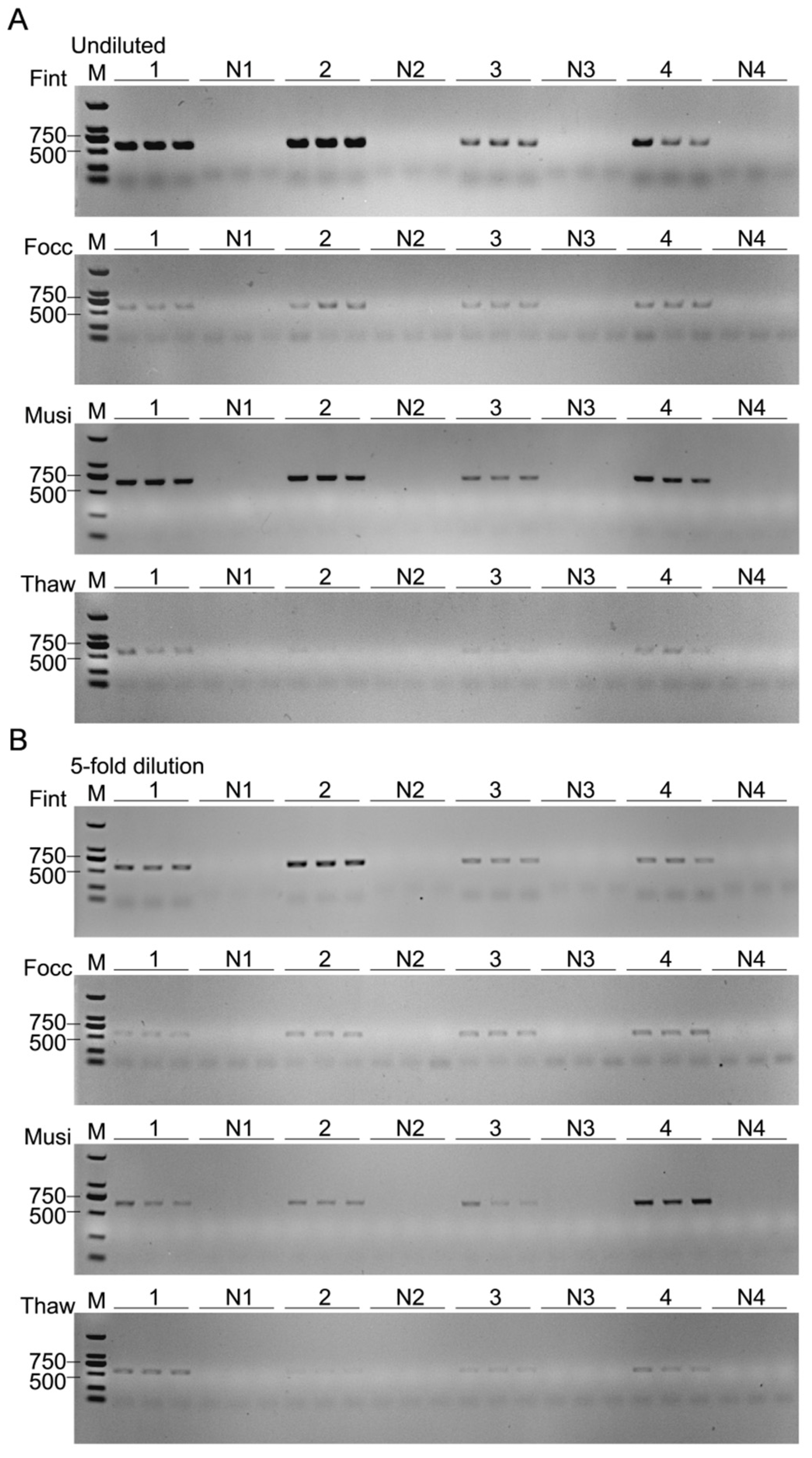

2.6. Determination of PCR Detection Sensitivity

Genomic DNA extracted from single adults of the four species was serially diluted to five concentration levels, corresponding to DNA inputs of 50 ng, 10 ng, 1 ng, 100 pg, and 10 pg per 25 μL PCR reaction. PCR amplification was conducted using the species-specific primer pairs designed for each thrips species, following the same reaction composition and thermal cycling parameters described in

Section 2.2. The amplified products were resolved on 1% agarose gels, and band visibility and clarity were evaluated to assess amplification performance across DNA input levels. The lowest DNA amount consistently producing a visually distinct and reproducible band was defined as the limit of detection (LOD) for each assay. Each DNA input level was conducted in three biological replicates to confirm reproducibility and reliability.

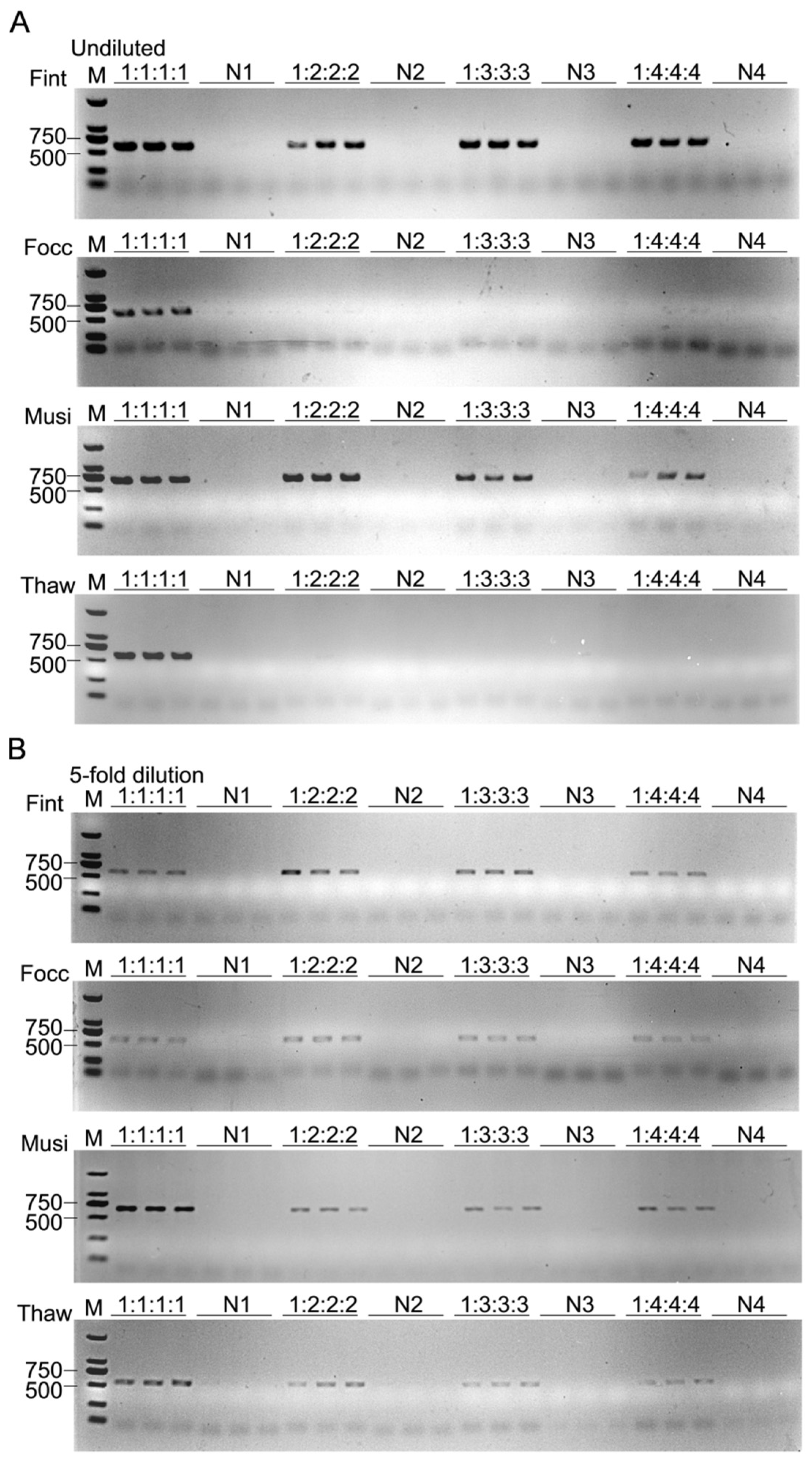

2.7. Evaluation of Species-Specific Sensitivity Across Mixed Population Ratios

To assess the detection sensitivity of target thrips across varying abundance ratios, a gradient mixture assay was conducted. Gradient mixtures were prepared by combining one adult of the target species with one to four individuals of each of the other three species, yielding target-to-background ratios of 1:1:1:1, 1:2:2:2, 1:3:3:3, and 1:4:4:4. Corresponding negative controls were prepared using the same ratios but excluding the target species (non-target thrips only). Each mixture was subsequently homogenized in 50 μL of 1× PBS using the PBS-based short-turnaround extraction protocol, ensuring consistency among treatments. Each treatment was performed with three biological replicates, and 1 μL of extracted DNA was used per PCR reaction to maintain consistent template input across assays.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Morphometric parameters (body length and width) and DNA extraction metrics (yield, purity, and storage stability) were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) calculated from ten biological replicates (

n = 10) per species. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA;

https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics (accessed on 14 January 2026)). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to compare means among treatments, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, with significance set at

p < 0.05. GraphPad Prism (version 9.0.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA;

https://www.graphpad.com/) was used for data visualization and figure preparation.

4. Discussion

The high taxonomic diversity and pronounced morphological similarity of thrips communities limit the reliability of conventional morphology-based identification, particularly when specimens are fragile or collected at variable developmental stages [

27,

28,

29]. To address these practical limitations, we established a species-specific molecular identification framework targeting the mitochondrial

COI region, which enables reproducible, target-specific amplification in both individual and mixed-species samples. Unlike conventional DNA barcoding approaches that rely on universal primers targeting conserved regions, followed by post-PCR sequencing and subsequent sequence alignment [

30,

31], our system employs a polymorphism-informed, 3′-terminal discriminatory primer design anchored in species-specific polymorphic sites, enabling selective amplification in combination with a PBS-based short-turnaround DNA extraction protocol that minimizes procedural complexity and enhances field compatibility. The resulting framework integrates a balance among analytical specificity, operational simplicity, and dilution-mitigated inhibition, providing a species-specific and reproducible molecular identification framework that is time-efficient compared with sequencing-based barcoding for thrips species of agricultural importance.

The mitochondrial

COI gene, characterized by a combination of conserved and hypervariable regions, remains the most widely used molecular marker for animal species identification owing to its robust interspecific resolution [

32,

33]. In this study, alignment of

COI sequences revealed polymorphism-enriched regions that supported species-specific discrimination while maintaining amplification efficiency. Although conventional DNA barcoding approaches based on universal primers and sequence alignment have greatly facilitated reference library development, they frequently suffer from cross-species amplification and ambiguous results in complex, mixed-species samples [

34,

35]. To overcome these limitations, we employed a polymorphism-guided, primer-level engineering strategy by introducing diagnostic substitutions at the 3′ terminus, leveraging the high sensitivity of DNA polymerase to terminal mismatches. Previous studies have demonstrated that even a single 3′-terminal mismatch can markedly inhibit polymerase extension, thereby preventing non-target amplification [

36,

37]. Accordingly, our terminal-mutation-driven primers yielded single, distinct amplicons for all four thrips species, with no detectable nonspecific products under mixed-template conditions. This design achieves a dynamic balance between specificity and sensitivity and demonstrates excellent reproducibility across biological replicates. Given that terminal mismatch discrimination is a universal property of DNA polymerase, this polymorphism-guided strategy has broad applicability across taxonomic groups. Because the diagnostic target is mitochondrial

COI, which is present in both females and males, the molecular assay itself is not inherently sex-specific and is therefore applicable to both sexes in molecular identification contexts. Beyond thrips, this approach provides a scalable framework for the short-turnaround identification of other small-bodied, morphologically similar pest species and represents a conceptual shift from conserved-region-dependent barcoding to polymorphism-guided molecular diagnosis [

38].

Sample preparation remains a primary bottleneck limiting the field-compatible deployment of molecular species identification workflows [

39,

40]. Although conventional CTAB protocols and commercial kits yield high-purity DNA, they are labor-intensive, reagent-intensive, and require specialized equipment, rendering them unsuitable for time-efficient, field-oriented workflows [

41]. In contrast, the PBS-based crude extraction method demonstrated the highest success rate in direct PCR, likely attributable to its isotonic nature, buffering capacity, and high compatibility with downstream molecular reactions. This PBS-based protocol simplifies sample preparation by eliminating multi-step DNA purification and centrifugation, thereby improving compatibility with direct PCR from single insects. Standard PBS is an isotonic buffer containing Na

+, K

+, and phosphate but lacking divalent cations, providing a chemically stable environment during crude lysis. PBS can dilute potential PCR inhibitors and stabilize pH, while high-temperature incubation (98 °C) simultaneously facilitates efficient nucleic acid release and denatures endogenous proteins, including nucleases, thereby reducing nucleic acid degradation and improving amplification reproducibility [

42,

43,

44]. These combined chemical and thermal effects synergistically enhance the compatibility of PBS lysates with standard DNA polymerase, enabling stable and specific amplification without purification [

45]. Collectively, these mechanisms reduce reliance on conventional purification procedures, streamline sample processing, and minimize nucleic acid loss during handling [

46]. Thus, PBS effectively preserves nucleic acid integrity while simplifying sample handling and enhancing assay compatibility, thereby providing reproducible templates for downstream amplification even under unpurified conditions.

Sensitivity is a key performance metric for the molecular species identification framework and is commonly quantified by the LOD, defined as the lowest target concentration that can be detected with acceptable reliability [

47]. In this study, clear and reproducible amplicons were consistently obtained at a template input of 1 ng, and faint but detectable bands were observed in some thrips samples at 0.1 ng, suggesting that the LOD falls within the theoretical sensitivity range of conventional PCR, where 1–1000 ng of DNA template is typically considered workable [

48]. Despite potential carryover of inhibitors from the short-turnaround lysis procedure, single, distinct amplicons were consistently obtained across all four thrips species, demonstrating that PCR inhibition was effectively alleviated under the tested dilution conditions. Although amplification remained reproducible overall, slight interspecific differences in band intensity were observed, suggesting that amplification efficiency may also be influenced by intrinsic sequence composition and structural features. GC-rich regions tend to form stable secondary structures, such as hairpins and G-quadruplexes, which hinder DNA polymerase extension under low-template conditions and thereby introduce amplification bias [

49]. At limiting template levels, amplification efficiency becomes highly sensitive to primer–template binding kinetics, and even minor mismatches near the 3′ terminus can impair polymerase initiation, further amplifying interspecific variation in amplicon yield. Collectively, these molecular mechanisms plausibly account for the species-specific variation observed in amplification and indicate that the system achieves a favorable balance between sensitivity and stability.

In complex field-derived samples, the coexistence of non-target individuals and interspecific differences in metabolic profiles may introduce diverse PCR inhibitors that interfere with amplification efficiency [

24,

50]. To mimic this complexity, gradient mixtures of multiple thrips species were constructed to systematically evaluate the alleviation of PCR inhibition under mixed-template scenarios. Pronounced matrix-associated inhibition was observed but proved reversible. Under undiluted conditions, stable amplification was consistently observed for

F. intonsa and

M. usitatus, whereas

F. occidentalis and

T. hawaiiensis exhibited progressively weaker or undetectable bands as the proportion of non-target species increased. Following fivefold dilution, clear and distinct species-specific bands were restored for all four species, indicating that the inhibitory effect primarily resulted from excessive inhibitor concentrations in the crude lysate and confirming the pivotal role of dilution in alleviating PCR inhibition [

51]. In thrips sample matrices, PCR inhibition likely arises from multiple sources acting in combination, broadly encompassing insect-derived and host plant-derived factors [

24,

25]. Insect-derived inhibitors include melanin and its precursors such as polyphenol oxidation products, chitin fragments, and protein residues, which can form nonspecific interactions with DNA polymerase and Mg

2+ ions, thereby reducing enzymatic activity [

24,

52,

53]. Additionally, components of the hemolymph phenoloxidase cascade may persist after lysis and suppress polymerase reactions [

54]. This hypothesis was further supported by the single species gradient experiment, which confirmed that lysates from

F. intonsa,

F. occidentalis, and

M. usitatus exerted minimal inhibitory effects on PCR, whereas

T. hawaiiensis exhibited a non-linear amplification trend, characterized by the weakest signal at intermediate sample sizes and partial recovery at higher inputs. This pattern likely arises from the opposing effects of increasing template concentration and the accumulation of inhibitory substances in crude lysates, leading to a concentration-dependent equilibrium between amplification and suppression. After moderate dilution, the same trend persisted with overall weaker intensity, indicating that both template and inhibitor concentrations jointly determine the amplification outcome. These observations suggest that PCR inhibition in thrips lysates is influenced not only by template complexity but also by differences in biochemical composition among species, which may modulate the balance between amplification efficiency and inhibitory effects.

The alleviation of PCR inhibition observed under PBS-based extraction and moderate dilution conditions is consistent with well-established principles of PCR chemistry. Compared with lysis buffers containing chelating agents or surfactants, PBS introduces fewer exogenous compounds that may interfere with polymerase activity, allowing amplification outcomes to more directly reflect endogenous sample components [

25,

42]. It is well recognized that PCR inhibitors can reduce polymerase efficiency through nonspecific interactions with the enzyme or essential reaction ions such as Mg

2+ [

24,

55]. Dilution reduces the effective concentration of such inhibitors and has been widely applied as a practical means to improve amplification performance in crude extracts [

52,

56,

57]. In this context, the improved amplification observed here is in line with existing knowledge that a balance between template availability and inhibitor load determines PCR success. Together, these observations illustrate the practical utility of combining PBS-based extraction with dilution for enhancing amplification compatibility in complex insect-derived samples.

Beyond these methodological advances in DNA extraction and inhibitor management, this system has substantial practical relevance for pest thrips management. In the context of routine surveillance and large-scale monitoring, species-resolved detection supports early recognition of invasive species, real-time surveillance of population dynamics, and timely adjustment of biological control strategies and insecticide applications [

58,

59,

60]. This capability is important because thrips species differ in their patterns of reproductive advantage and competitive displacement, making accurate identification before visible field symptoms appear critical for minimizing crop losses and avoiding unnecessary chemical inputs. Although adult thrips can often be identified morphologically by trained taxonomists under laboratory conditions, accurate determination becomes challenging during early infestations, in mixed-species samples, or in large-scale monitoring associated with plant trade and seedling circulation chains. Under such circumstances, the compatibility of the assay with single-adult crude lysates enables standardized and reproducible species-level identification without slide preparation or reliance on specialist taxonomic expertise, thereby facilitating routine monitoring during seedling circulation, flower transport, and trans-regional crop movement, which represent major dissemination pathways for

F. occidentalis and other invasive thrips species and directly linking species-level diagnosis to management decisions.

Despite being reproducible under mixed-species backgrounds and strong inhibitor tolerance demonstrated across both laboratory- and field-derived samples, certain overarching limitations remain. One limitation of the present study lies in the reliance of primer design on

COI haplotypes representing dominant regional populations, a constraint that ultimately reflects the incomplete geographic coverage and taxonomic representation of publicly available

COI reference databases. Although additional haplotypes from geographically distant regions have been reported, comprehensive incorporation of all global variants was beyond the scope of this work. This limitation is not unique to the present study but is inherent to molecular species identification frameworks based on mitochondrial

COI markers, particularly those employing species-specific primer sets. When uncharacterized haplotypes or closely related taxa are encountered, such assays may exhibit non-amplification or, in rare cases, erroneous assignment, underscoring the importance of continued expansion and curation of reference databases. Nevertheless, within the populations examined here, the molecular species identification framework demonstrated species-specific and reproducible amplification across both single-species and mixed-species samples, supporting its practical applicability to laboratory-based surveillance workflows. Future expansion of geographic sampling and haplotype diversity will further extend the applicability of this molecular species identification framework beyond the four thrips species validated in this study [

61,

62,

63]. Moreover, the assay still relies on thermocycler-based PCR and has yet to achieve true portability or real-time field-oriented workflow. Although the PBS-based protocol simplifies sample preparation, it still requires brief thermal treatment, which currently limits its full deployment under equipment-free field conditions. To overcome these constraints, emerging visual isothermal amplification technologies, such as RPA-Cas12a, have shown great promise for field-compatible molecular identification, combining minimal instrument requirements with high analytical sensitivity demonstrated across diverse insect pest and pathogen systems [

64,

65,

66]. Integrating this detection framework with portable readout devices could enable a field-compatible molecular platform that automates workflows from molecular identification to pest surveillance, thereby advancing molecular identification tools toward field-adaptable and data-driven applications.