Systematic Evaluation of a Mouse Model of Aging-Associated Parkinson’s Disease Induced with MPTP and D-Galactose

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Drugs and Reagents

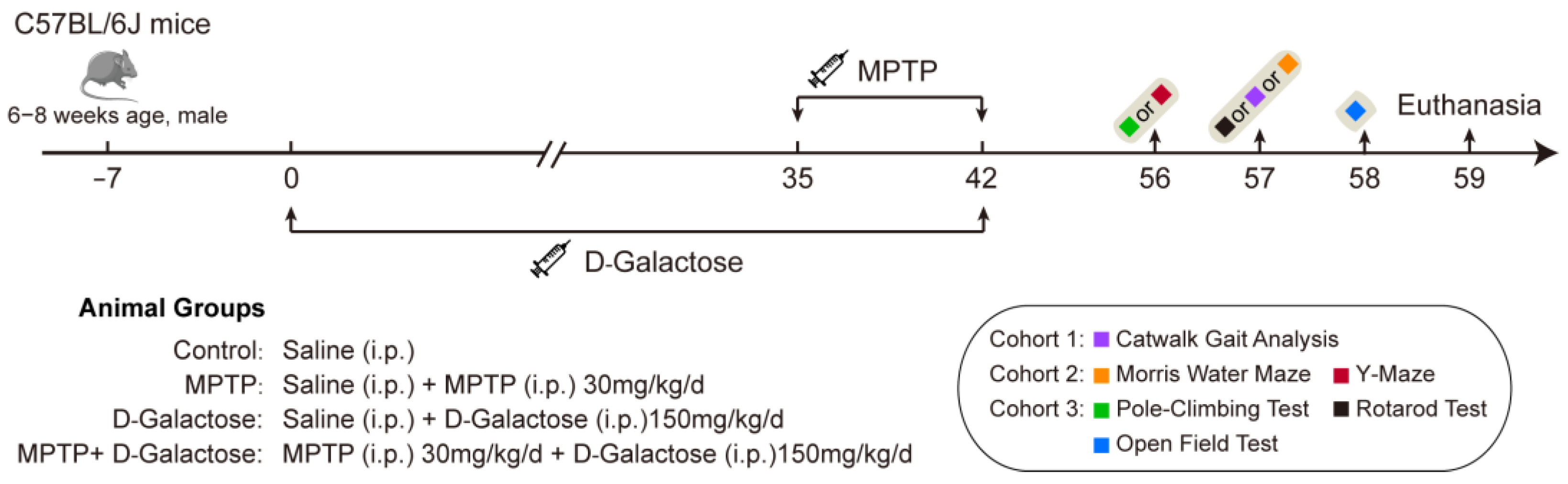

2.3. Experimental Design and PD Model Construction

2.4. Behavioral Tests

2.4.1. Pole-Climbing Test

2.4.2. Rotarod Test

2.4.3. Open Field Test

2.4.4. CatWalk XT Analysis

2.4.5. Morris Water Maze

2.4.6. Y-Maze

2.5. Animal Tissue Sampling

2.6. Immunofluorescence

2.7. Micro-CT Imaging and Analysis for Animals

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

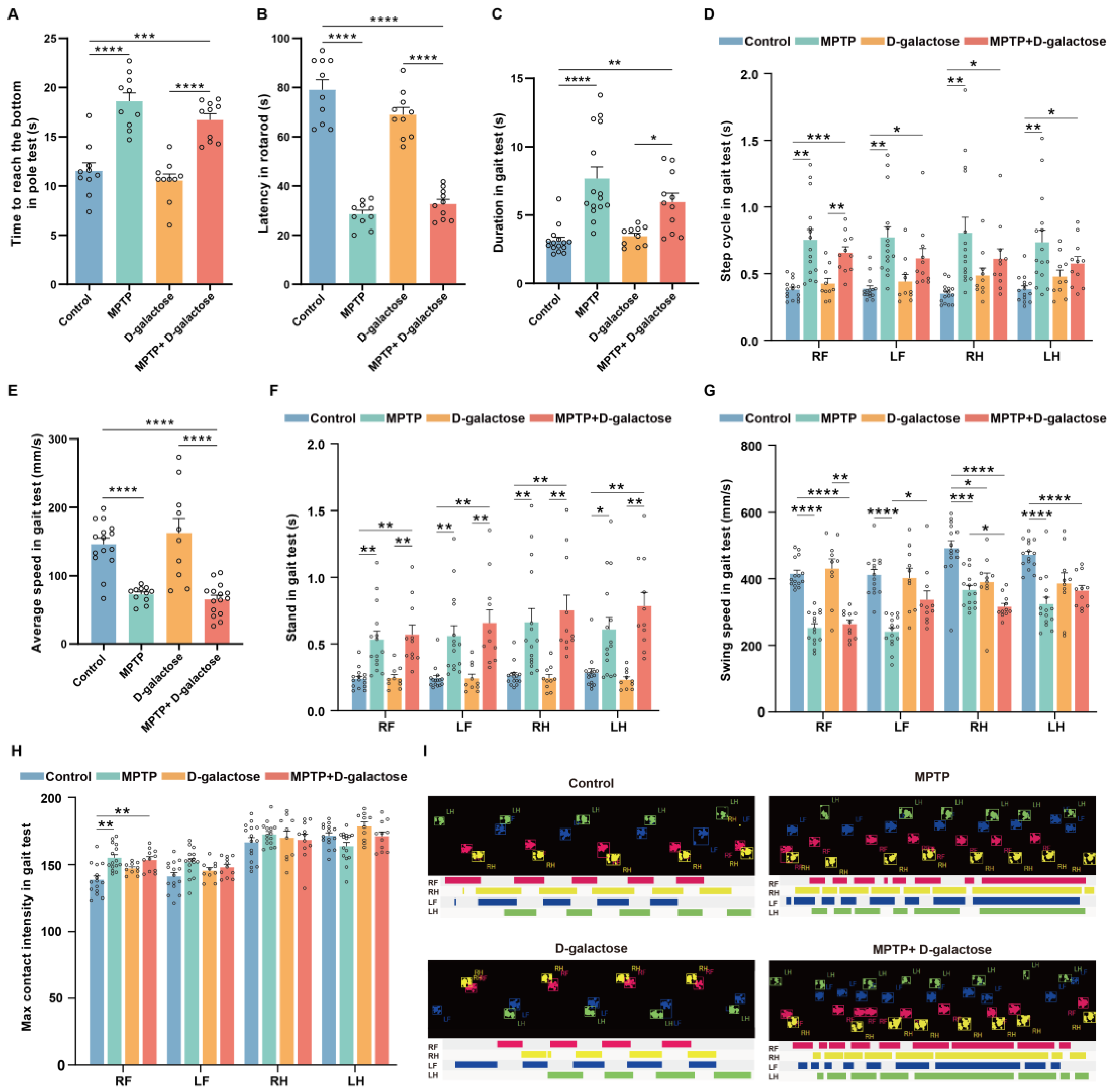

3.1. MPTP + D-Galactose Induced Motor Disorders in Mice Similar to MPTP

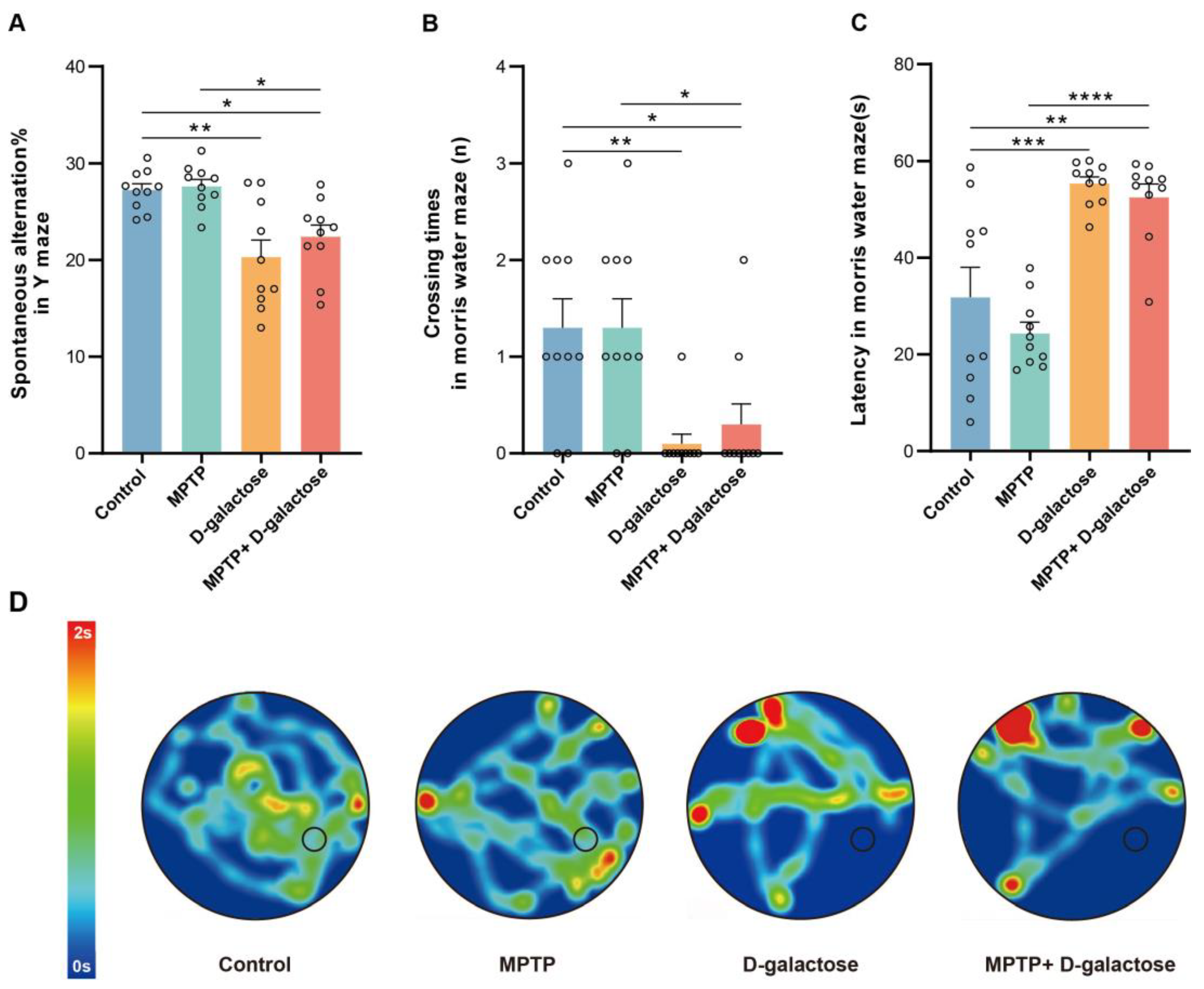

3.2. MPTP + D-Galactose but Not MPTP Induced Spatial Learning and Memory Deficits in Mice

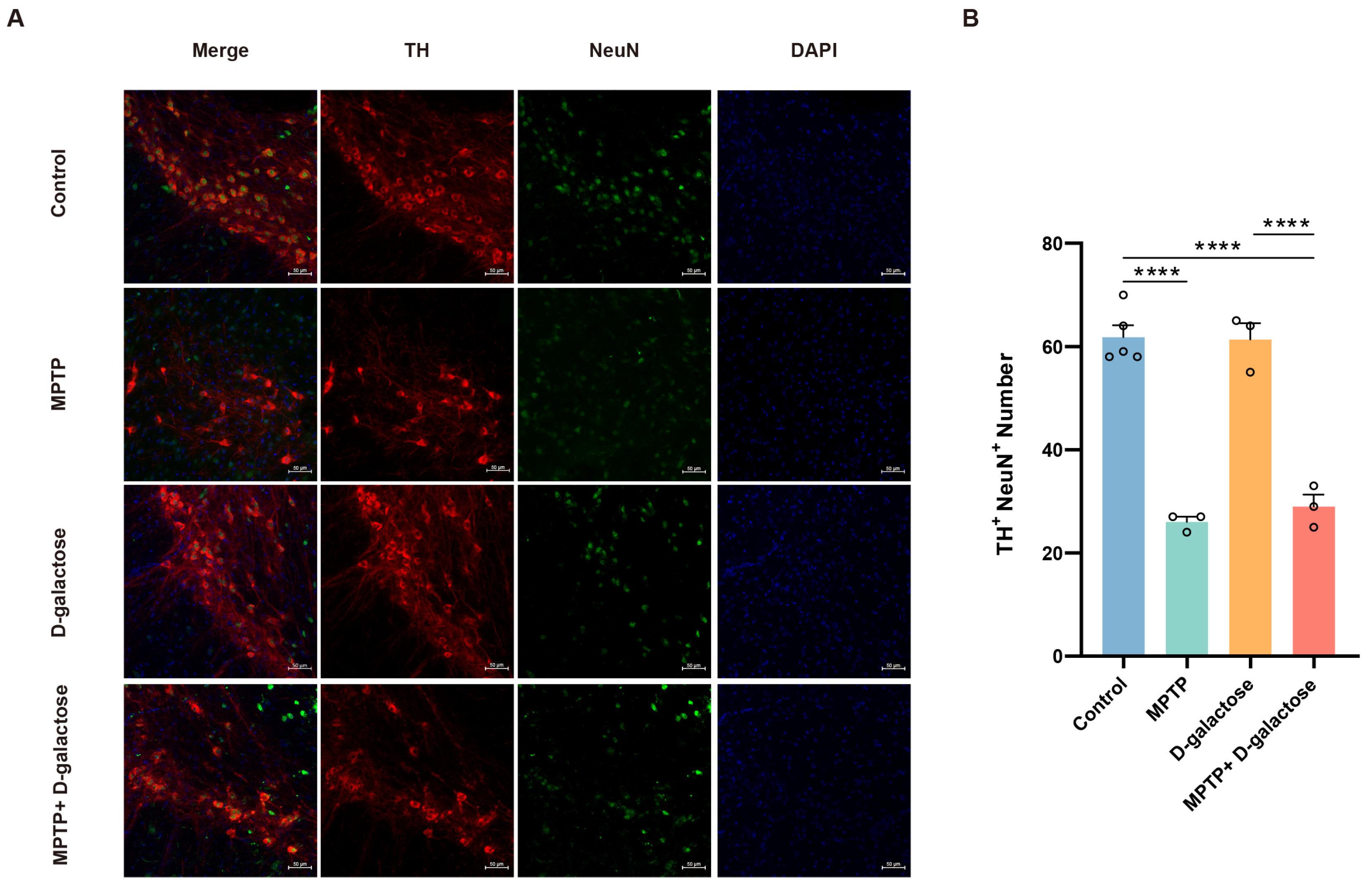

3.3. MPTP + D-Galactose Induced Typical Pathological Changes in Mice Similar to MPTP

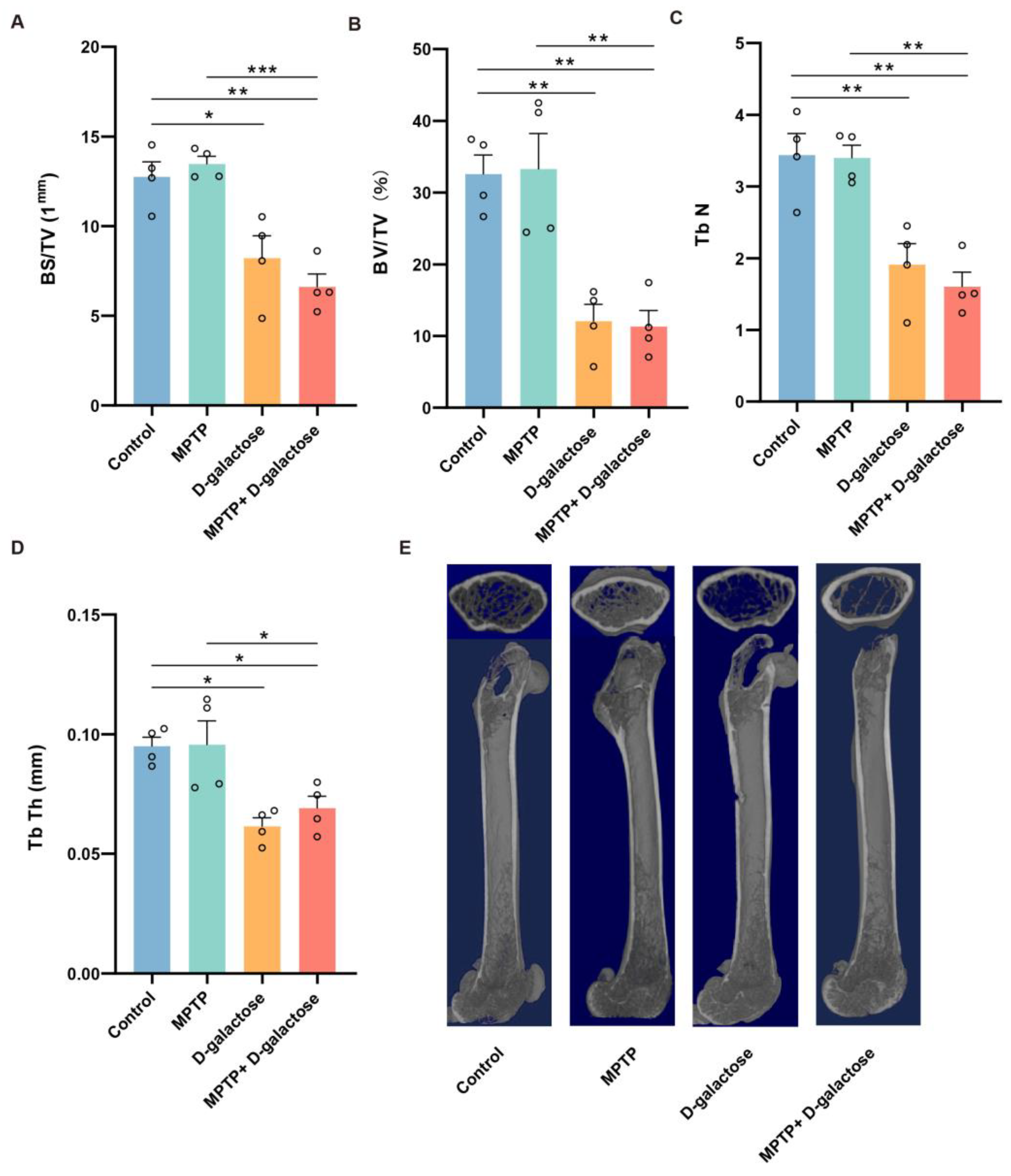

3.4. MPTP + D-Galactose but Not MPTP Induced Bone Loss in Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| MPTP | 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6tetrahydropyridine |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde Fix Solution |

| TH | Tyrosine Hydroxylase |

| NeuN | Neuron-specific Nuclear |

| SNc | substantia nigra pars compacta |

References

- Lees, A.J. Impact Commentaries. A modern perspective on the top 100 cited JNNP papers of all time: The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2012, 83, 954–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; Nichols, E.; Alam, T.; Bannick, M.S.; Beghi, E.; Blake, N.; Culpepper, W.J.; Dorsey, E.R.; Elbaz, A.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovo, J.; Allende-Castro, C.; Laliena, A.; Guerrero, N.; Silva, H.; Concha, M.L. Changes in neural circuitry associated with depression at pre-clinical, pre-motor and early motor phases of Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2017, 35, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsworth, J.D. Parkinson’s disease treatment: Past, present, and future. J. Neural Transm. 2020, 127, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Ru, Q.; Chen, L.; Xu, G.; Wu, Y. Advances in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2024, 215, 111024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, M.; Ang, M.J.; Weerasinghe-Mudiyanselage, P.D.E.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.C.; Shin, T.; Moon, C. Behavioral characterization in MPTP/p mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2021, 20, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masilamoni, G.J.; Smith, Y. Chronic MPTP administration regimen in monkeys: A model of dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic cell loss in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2018, 125, 337–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merghani, M.M.; Ardah, M.T.; Al Shamsi, M.; Kitada, T.; Haque, M.E. Dose-related biphasic effect of the Parkinson’s disease neurotoxin MPTP, on the spread, accumulation, and toxicity of α-synuclein. Neurotoxicology 2021, 84, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sai, T.; Uchida, K.; Nakayama, H. Biochemical evaluation of the neurotoxicity of MPTP and MPP+ in embryonic and newborn mice. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2013, 38, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, H.S.; Dunnett, S.B. Cognitive dysfunction and depression in Parkinson’s disease: What can be learned from rodent models? Eur. J. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 1894–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, K.; Chesselet, M.F. Animal models of the non-motor features of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 46, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czernecki, V.; Pillon, B.; Houeto, J.L.; Pochon, J.B.; Levy, R.; Dubois, B. Motivation, reward, and Parkinson’s disease: Influence of dopatherapy. Neuropsychologia 2002, 40, 2257–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqué, C.; Ramírez-Ruiz, B.; Tolosa, E.; Summerfield, C.; Martí, M.J.; Pastor, P.; Gómez-Ansón, B.; Mercader, J.M. Amygdalar and hippocampal MRI volumetric reductions in Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2005, 20, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N.; Tolosa, E.; Junque, C.; Marti, M.J. MRI and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2009, 24, S748–S753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S.R.; Chesselet, M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2013, 106–107, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, B.; Caridade-Silva, R.; Soares-Guedes, C.; Martins-Macedo, J.; Gomes, E.D.; Monteiro, S.; Teixeira, F.G. Neuroinflammation and Parkinson’s Disease-From Neurodegeneration to Therapeutic Opportunities. Cells 2022, 11, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.Y. Synaptic and cellular plasticity in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swomley, A.M.; Butterfield, D.A. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment: Evidence from human data provided by redox proteomics. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 1669–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.W.; Jo, S.W.; Kim, D.E.; Paik, I.Y.; Balakrishnan, R. Aerobic exercise attenuates LPS-induced cognitive dysfunction by reducing oxidative stress, glial activation, and neuroinflammation. Redox Biol. 2024, 71, 103101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honer, W.G.; Ramos-Miguel, A.; Alamri, J.; Sawada, K.; Barr, A.M.; Schneider, J.A.; Bennett, D.A. The synaptic pathology of cognitive life. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 21, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, K.F.; Zakaria, R. D-Galactose-induced accelerated aging model: An overview. Biogerontology 2019, 20, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Xia, T.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, N.; Xin, H. Protective effects of bitter acids from Humulus lupulus L. against senile osteoporosis via activating Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 pathway in D-galactose induced aging mice. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 94, 105099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liu, X.; He, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, N.; Qin, L.; Xin, H. Bajitianwan attenuates D-galactose-induced memory impairment and bone loss through suppression of oxidative stress in aging rat model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 261, 112992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, S.L.; Hu, W.J.; Wang, S.N.; Zhao, Y.; Miao, C.Y. Metrnl regulates cognitive dysfunction and hippocampal BDNF levels in D-galactose-induced aging mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, W.; Deng, P.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, L.; Li, C.; Gao, H. Fibroblast growth factor 21 ameliorates behavior deficits in Parkinson’s disease mouse model via modulating gut microbiota and metabolic homeostasis. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 3815–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Yang, P.; Zhao, R.; Bai, Y.; Guo, Z. Matrine Attenuates D-Galactose-Induced Aging-Related Behavior in Mice via Inhibition of Cellular Senescence and Oxidative Stress. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 7108604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.L.; Xie, X.H.; Ding, J.H.; Du, R.H.; Hu, G. Astragaloside IV inhibits astrocyte senescence: Implication in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Sun, W.; Shen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, M.; Liu, A.; Ma, H.; Lai, X.; Wu, J. Idebenone improves motor dysfunction, learning and memory by regulating mitophagy in MPTP-treated mice. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.S.; Heng, Y.; Mou, Z.; Huang, J.Y.; Yuan, Y.H.; Chen, N.H. Reassessment of subacute MPTP-treated mice as animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J.; Kovalenko, O.; Younsi, A.; Grutza, M.; Unterberg, A.; Zweckberger, K. The CatWalk XT® is a valid tool for objective assessment of motor function in the acute phase after controlled cortical impact in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2020, 392, 112680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Qu, A.; Wang, W.; Lu, M.; Shi, B.; Chen, C.; Hao, C.; Xu, L.; Sun, M.; Xu, C.; et al. Facet-Dependent Biodegradable Mn(3) O(4) Nanoparticles for Ameliorating Parkinson’s Disease. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, e2101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hu, W.; Qu, L.; Wang, J.; Wu, A.; Lo, H.H.; Ng, J.P.L.; Tang, Y.; Yun, X.; Wu, J.; et al. Tricin promoted ATG-7 dependent autophagic degradation of α-synuclein and dopamine release for improving cognitive and motor deficits in Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 196, 106874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.S.; Xu, S.Y.; Jiang, Y.P.; Li, K.; Zhu, R.Q.; Han, T.; Xin, H.L. Therapeutic potential of xanthohumol in senile osteoporosis: mTOR-driven regulation of AKT/mTOR/p70S6K autophagy axis in D-galactose models. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2025, 148, 157346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, L.; Chi, X.; Sun, Y.; Han, C.; Wan, F.; Hu, J.; Yin, S.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; et al. The circadian clock protein Rev-erbα provides neuroprotection and attenuates neuroinflammation against Parkinson’s disease via the microglial NLRP3 inflammasome. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Liu, M.; Jiang, H.; Qiao, Z.; Ren, K.; Du, X.; Chen, X.; Jiao, Q.; Che, F. Repurposing of epalrestat for neuroprotection in parkinson’s disease via activation of the KEAP1/Nrf2 pathway. J. Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikereya, T.; Liu, C.; Wei, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Han, C.; Shi, K.; Chen, W. The cannabinoid receptor 1 mediates exercise-induced improvements of motor skill learning and performance in parkinsonian mouse. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 391, 115289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirik, D.; Rosenblad, C.; Björklund, A. Characterization of behavioral and neurodegenerative changes following partial lesions of the nigrostriatal dopamine system induced by intrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 1998, 152, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.Q.; Zheng, R.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Lin, Z.H.; Xue, N.J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, B.R.; Pu, J.L. Parkin regulates microglial NLRP3 and represses neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e13834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Yu, J. Lactoferrin ameliorates cognitive impairment in D-galactose-induced aging mice by regulating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 309, 143033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, R.; Wang, W.; Deng, Q.; Cao, C.; Yu, C.; Li, S.; Shi, L.; Tian, J. Activation of α7nAChR by PNU282987 improves cognitive impairment through inhibiting oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in D-galactose induced aging via regulating α7nAChR/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 175, 112139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Fu, S.; Wen, J.; Yan, A.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; He, D. Orally Administered Ginkgolide C Alleviates MPTP-Induced Neurodegeneration by Suppressing Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress through Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 22115–22131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.; Granert, O.; Timmers, M.; Pilotto, A.; Van Nueten, L.; Roeben, B.; Salvadore, G.; Galpern, W.R.; Streffer, J.; Scheffler, K.; et al. Association of Hippocampal Subfields, CSF Biomarkers, and Cognition in Patients With Parkinson Disease Without Dementia. Neurology 2021, 96, e904–e915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, L.; Pan, J.X.; Guo, H.H.; Mei, L.; Xiong, W.C. Parkinson’s in the bone. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Huang, K.; Lu, Q.; Geng, W.; Jiang, D.; Guo, A. TRIM16 mitigates impaired osteogenic differentiation and antioxidant response in D-galactose-induced senescent osteoblasts. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 979, 176849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Ren, J.; Li, Z.; Qiu, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Hu, M.; Chen, D.; et al. Systematic Evaluation of a Mouse Model of Aging-Associated Parkinson’s Disease Induced with MPTP and D-Galactose. Biology 2026, 15, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020169

Liu T, Liu X, Chen Q, Ren J, Li Z, Qiu X, Wang X, Wu L, Hu M, Chen D, et al. Systematic Evaluation of a Mouse Model of Aging-Associated Parkinson’s Disease Induced with MPTP and D-Galactose. Biology. 2026; 15(2):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020169

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Tongzheng, Xiaoyu Liu, Qiuyue Chen, Jinfeng Ren, Zifa Li, Xiao Qiu, Xinyu Wang, Lidan Wu, Minghui Hu, Dan Chen, and et al. 2026. "Systematic Evaluation of a Mouse Model of Aging-Associated Parkinson’s Disease Induced with MPTP and D-Galactose" Biology 15, no. 2: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020169

APA StyleLiu, T., Liu, X., Chen, Q., Ren, J., Li, Z., Qiu, X., Wang, X., Wu, L., Hu, M., Chen, D., Zhang, H., & Geng, X. (2026). Systematic Evaluation of a Mouse Model of Aging-Associated Parkinson’s Disease Induced with MPTP and D-Galactose. Biology, 15(2), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020169