Laboratory Rearing of the Photosynthetic Sea Slug Elysia crispata (Gastropoda, Sacoglossa): Implications for the Study of Kleptoplasty and Species Conservation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

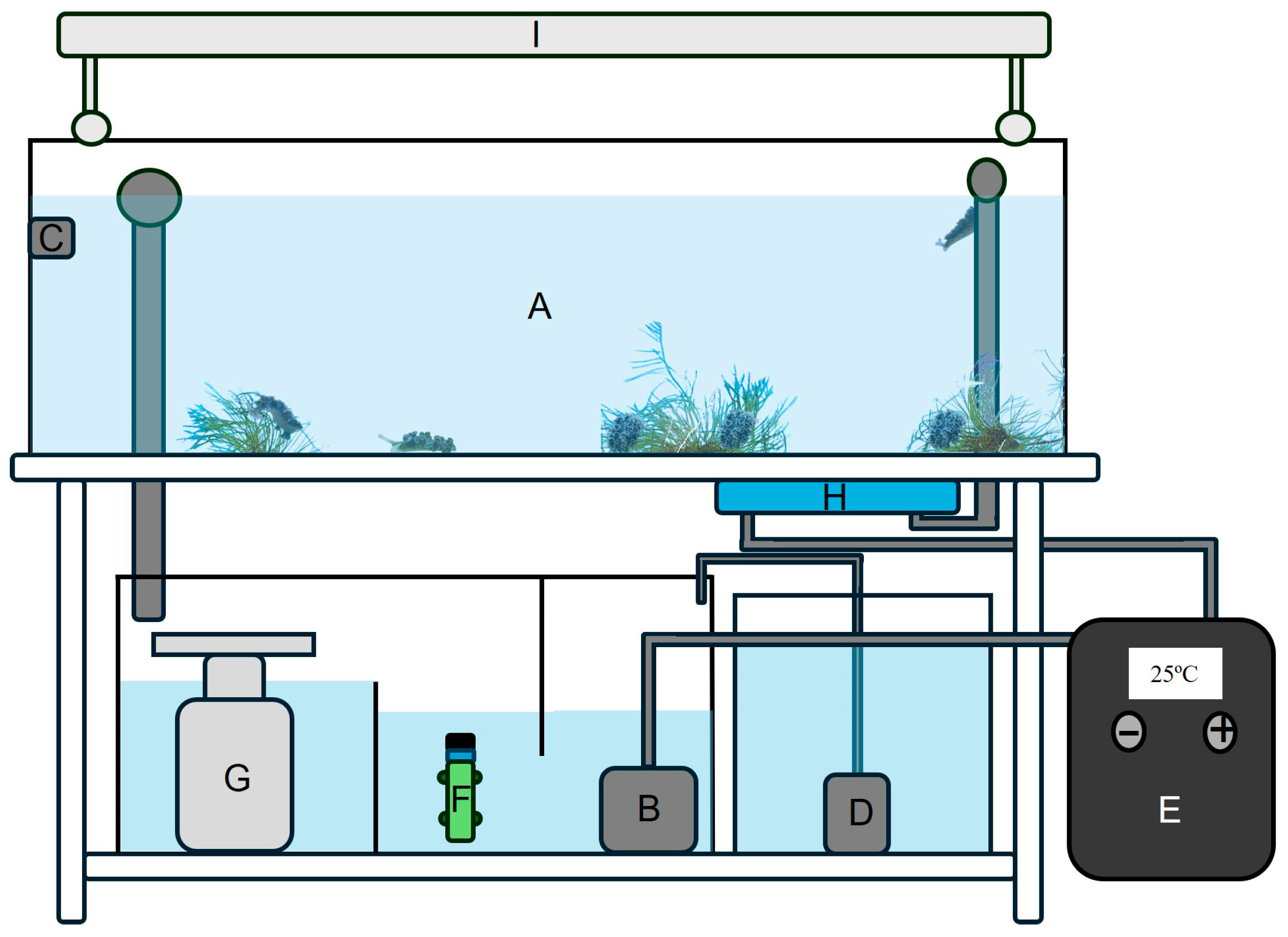

2.1. Animal Acclimatation and Maintenance

2.2. Algae Culturing

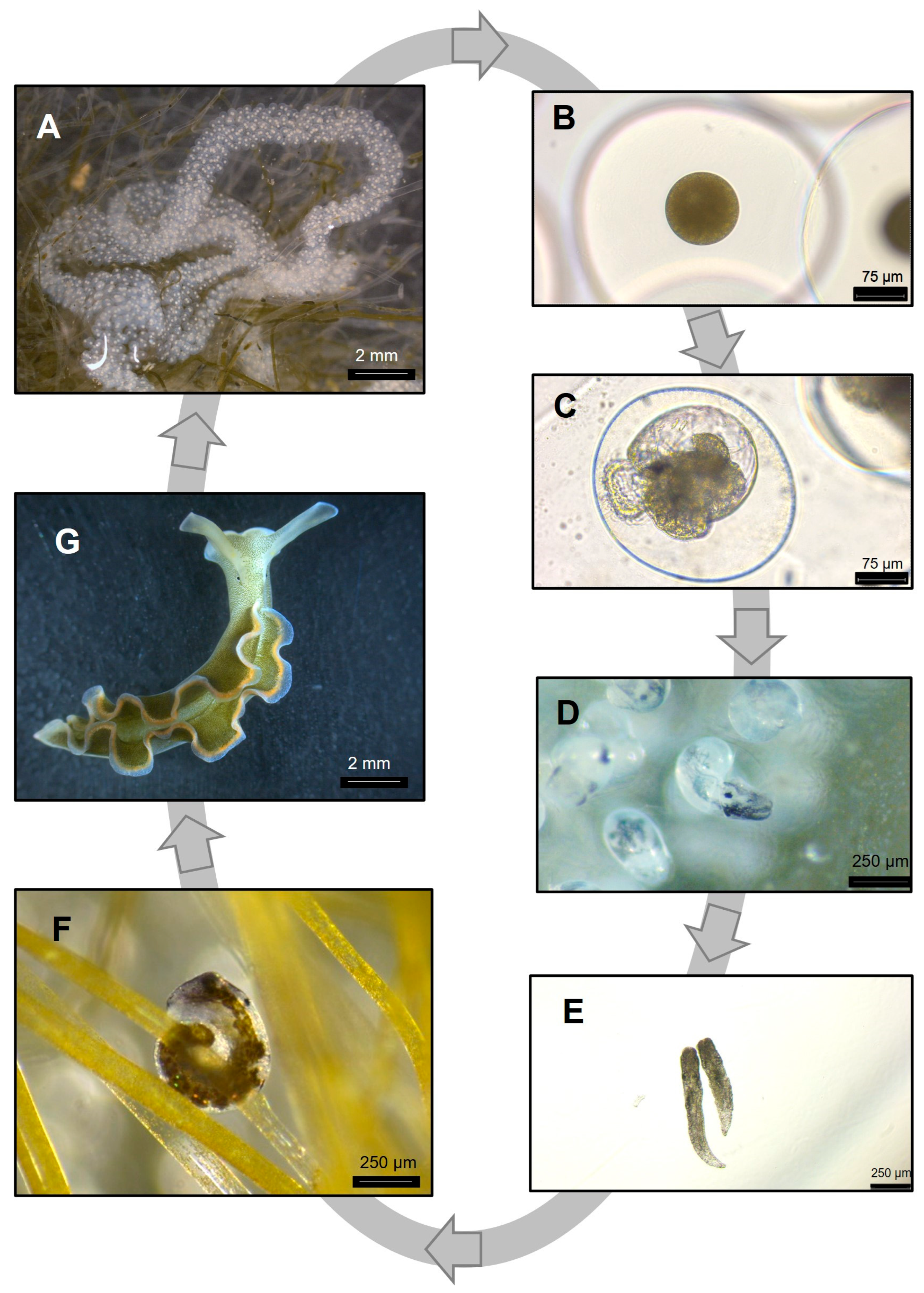

2.3. Spawning and Larval Development

2.4. Juvenile to Adult Transition

2.5. Group Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Life Cycle

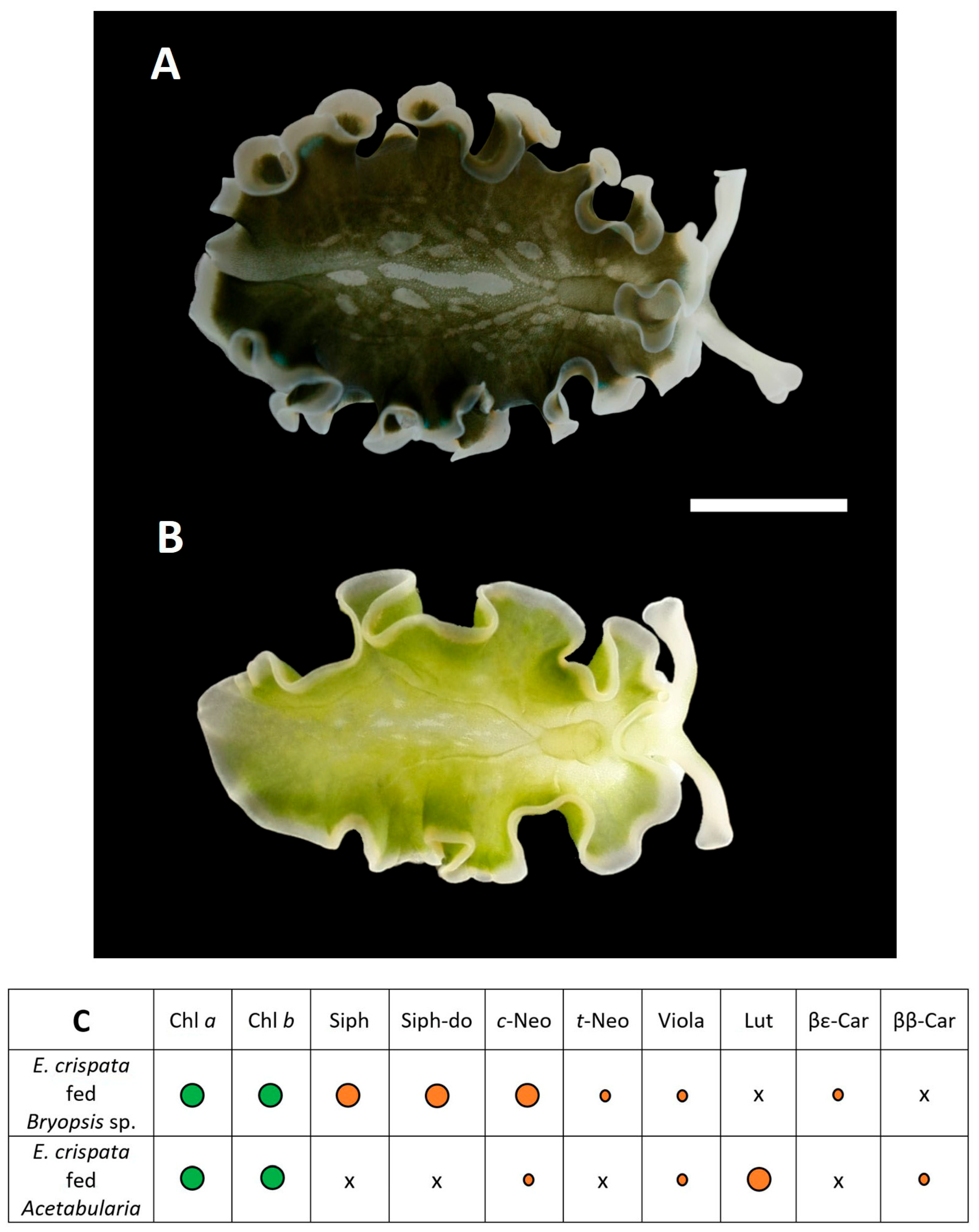

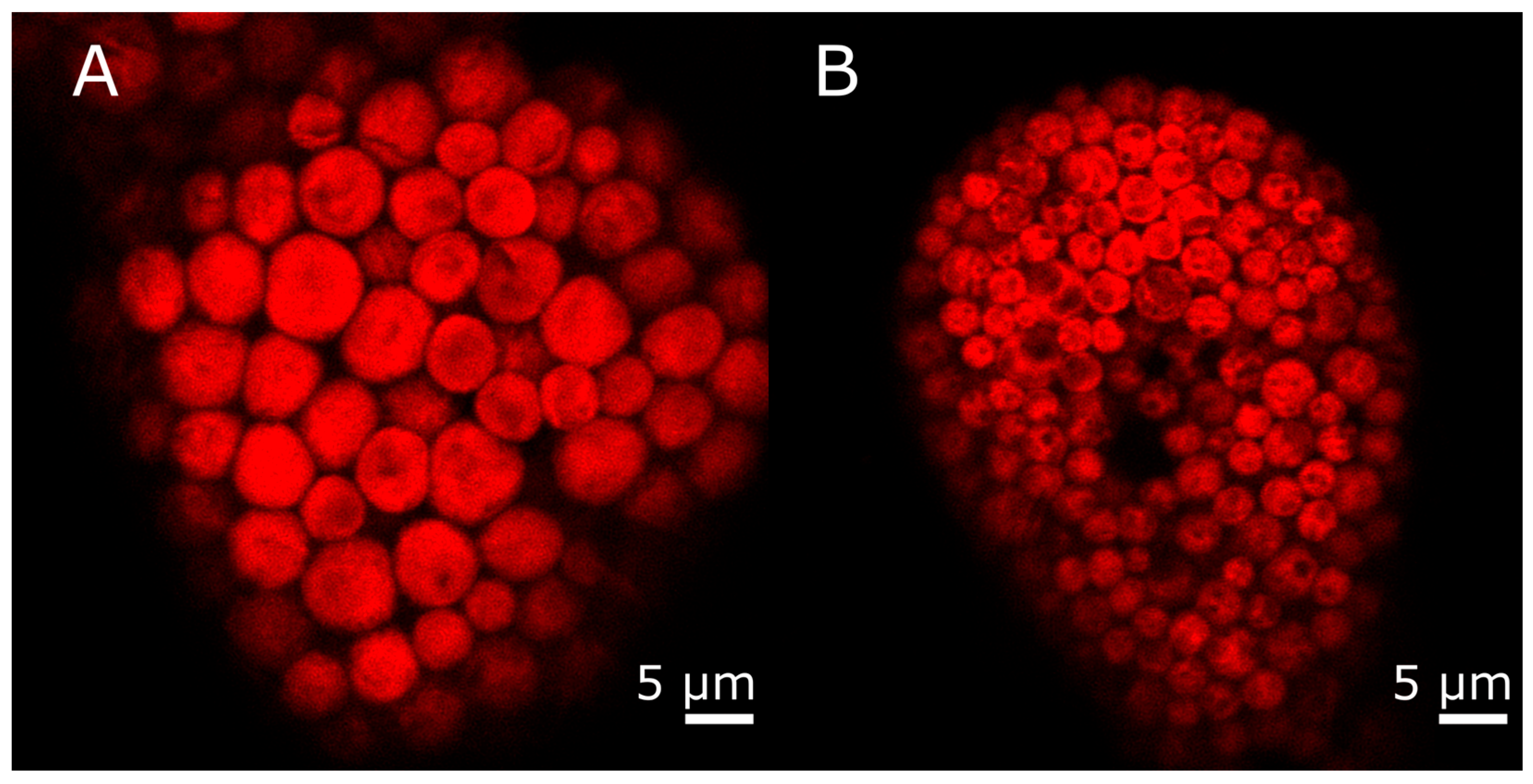

3.2. Kleptoplast Origin

4. Discussion

4.1. Rearing of Elysia crispata

4.2. Relevance of Captive Culture for the Study of Kleptoplasty

4.3. Elysia crispata Versus Other Kleptoplastic Sea Slugs as a Laboratory Model System

4.4. The Marine Aquarium Trade and Species Conservation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dionísio, G.; Rosa, R.; Leal, M.C.; Cruz, S.; Brandão, C.; Calado, G.; Serôdio, J.; Calado, R. Beauties and beasts: A portrait of sea slugs aquaculture. Aquaculture 2013, 408–409, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L.L. Aplysia. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, R60–R61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltzley, M.J.; Lohmann, K.J. Comparative study of TPep-like immunoreactive neurons in the central nervous system of nudibranch molluscs. Brain Behav. Evol. 2008, 72, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, M.C.; Puga, J.; Serôdio, J.; Gomes, N.C.M.; Calado, R. Trends in the discovery of new marine natural products from invertebrates over the last two decades—Where and what are we bioprospecting? PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpho, M.E.; Summer, E.J.; Manhart, J.R. Solar-powered sea slugs. Mollusc/algal chloroplast symbiosis. Plant Physiol. 2000, 123, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.; Cartaxana, P. Kleptoplasty: Getting away with stolen chloroplasts. PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allard, C.A.H.; Thies, A.B.; Mitra, R.; Vaelli, P.M.; Leto, O.D.; Walsh, B.L.; Laetz, E.M.J.; Tresguerres, M.; Lee, A.S.Y.; Bellono, N.W. A host organelle integrates stolen chloroplasts for animal photosynthesis. Cell 2025, 188, 5266–5277.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calado, R. The need for cultured specimens. In Marine Ornamental Species Aquaculture; Calado, R., Olivotto, I., Oliver, M.P., Holt, G.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Krug, P.J.; Vendetti, J.E.; Valdés, Á. Molecular and morphological systematics of Elysia Risso, 1818 (Heterobranchia: Sacoglossa) from the Caribbean region. Zootaxa 2016, 4148, 1–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, S.; Curtis, N.; Massey, S.; Bass, A.; Karl, S.; Finney, C. A morphological and molecular comparison between Elysia crispata and a new species of kleptoplastic sacoglossan sea slug (Gastropoda: Opisthobranchia) from the Florida Keys, USA. Molluscan Res. 2006, 26, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, P.; Middlebrooks, M.L. Bacterial diversity associated with the “clarki” ecotype of Elysia crispata Mörch. Microbiologyopen 2020, 9, e1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, K.E.; Pendleton, A.L.; Shaikh, M.A.; Suttiyut, T.; Ogas, R.; Tomko, P.; Gavelis, G.; Widhalm, J.R.; Wisecaver, J.H. A reference genome for the long-term kleptoplast-retaining sea slug Elysia crispata morphotype clarki. G3 2023, 13, jkad234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strathmann, R.R. Feeding and nonfeeding larval development and life-history evolution in marine invertebrates. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1985, 16, 339–361. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2097052 (accessed on 14 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Arrieche, D.; Ugarte, A.; Salazar, F.; Villamizar, J.E.; Rivero, N.; Caballer, M.; Llovera, L.; Montañez, J.; Taborga, L.; Quintero, A. Reassignment of crispatene, isolation and chemical characterization of stachydrine, isolated from the marine mollusk Elysia crispata. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 4013–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlebrooks, M.L.; Bell, S.S.; Curtis, N.E.; Pierce, S.K. Atypical plant–herbivore association of algal food and a kleptoplastic sea slug (Elysia clarki) revealed by DNA barcoding and field surveys. Mar. Biol. 2014, 161, 1429–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlebrooks, M.; Curtis, N.; Pierce, S. Algal sources of sequestered chloroplasts in the sacoglossan sea slug Elysia crispata vary by location and ecotype. Biol. Bull. 2019, 236, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vital, X.G.; Rey, F.; Cartaxana, P.; Cruz, S.; Domingues, M.R.; Calado, R.; Simões, N. Pigment and fatty acid heterogeneity in the sea slug Elysia crispata is not shaped by habitat depth. Animals 2021, 11, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, N.E.; Pierce, S.K.; Massey, S.E.; Schwartz, J.A.; Maugel, T.K. Newly metamorphosed Elysia clarki juveniles feed on and sequester chloroplasts from algal species different from those utilized by adult slugs. Mar. Biol. 2007, 150, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christa, G.; Händeler, K.; Kück, P.; Vleugels, M.; Franken, J.; Karmeinski, D.; Wägele, H. Phylogenetic evidence for multiple independent origins of functional kleptoplasty in Sacoglossa (Heterobranchia, Gastropoda). Org. Divers. Evol. 2015, 15, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, N.E.; Middlebrooks, M.L.; Mahadevan, P.; Pierce, S.K. A methodological note on using next generation sequencing technology to identify the algal sources of stolen chloroplasts in a single sea slug specimen (Elysia crispata) to provide a comprehensive view of the animal’s kleptoplast population. Symbiosis 2023, 89, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartaxana, P.; Morelli, L.; Cassin, E.; Havurinne, V.; Cabral, M.; Cruz, S. Prey species and abundance affect growth and photosynthetic performance of the polyphagous sea slug Elysia crispata. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 230810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, B.E.; Mandoli, D.F. Axenic cultures of Acetabularia (Chlorophyta): A decontamination protocol with potential application to other algae. J. Phycol. 1992, 28, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havurinne, V.; Rivoallan, A.; Mattila, H.; Tyystjärvi, E.; Cartaxana, P.; Cruz, S. Loss of state transitions in Bryopsidales macroalgae and kleptoplastic sea slugs (Gastropoda, Sacoglossa). Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.; Dionísio, G.; Rosa, R.; Calado, R.; Serôdio, J. Anesthetizing solar-powered sea slugs for photobiological studies. Biol. Bull. 2012, 223, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, P.J. Not My ‘Type’: Larval dispersal dimorphisms and bet-hedging in opisthobranch life histories. Biol. Bull. 2009, 216, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, L.; Havurinne, V.; Madeira, D.; Martins, P.; Cartaxana, P.; Cruz, S. Photoprotective mechanisms in Elysia species hosting Acetabularia chloroplasts shed light on host-donor compatibility in photosynthetic sea slugs. Physiol Plant. 2024, 176, e14273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgués-Palau, L.; Senna, G.; Laetz, E.M.J. Crawl away from the light! Assessing behavioral and physiological photoprotective mechanisms in tropical solar-powered sea slugs exposed to natural light intensities. Mar. Biol. 2024, 171, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vital, X.G.; Simões, N.; Cruz, S.; Mascaró, M. Photosynthetic animals and where to find them: Abundance and size of a solar-powered sea slug in different light conditions. Mar. Biol. 2023, 170, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, D.; Cunha, E.; Conde, T.; Moreira, A.; Cruz, S.; Domingues, P.; Oliveira, M.; Cartaxana, P. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of the mucus of the tropical sea slug Elysia crispata. Molecules 2024, 29, 4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giossi, C.E.; Cruz, S.; Rey, F.; Marques, R.; Melo, T.; Domingues, M.R.; Cartaxana, P. Light induced changes in pigment and lipid profiles of Bryopsidales algae. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 745083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, F.; Cartaxana, P.; Cruz, S.; Melo, T.; Domingues, M.R. Revealing the polar lipidome, pigment profiles, and antioxidant activity of the giant unicellular green alga, Acetabularia acetabulum. J. Phycol. 2023, 59, 1025–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, V.; Händeler, K.; Gunkel, S.; Escande, M.L.; Menzel, D.; Gould, S.B.; Martin, W.F.; Wägele, H. Chloroplast incorporation and long-term photosynthetic performance through the life cycle in laboratory cultures of Elysia timida (Sacoglossa, Heterobranchia). Front. Zool. 2014, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartaxana, P.; Rey, F.; LeKieffre, C.; Lopes, D.; Hubas, C.; Spangenberg, E.J.; Escrig, S.; Jesus, B.; Calado, G.; Domingues, R.; et al. Photosynthesis from stolen chloroplasts can support sea slug reproductive fitness. Proc. R. Soc. B 2021, 288, 20211779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, J.; Woehle, C.; Christa, G.; Wägele, H.; Tielens, A.G.M.; Jahns, P.; Gould, S.B. Comparison of sister species identifies factors underpinning plastid compatibility in green sea slugs. Proc. R. Soc. B 2015, 282, 20142519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowbridge, C.D. The missing links: Larval and post-larval development of the ascoglossan opisthobranch Elysia viridis. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2000, 80, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletreau, K.N.; Worful, J.M.; Sarver, K.E.; Rumpho, M.E. Laboratory culturing of Elysia chlorotica reveals a shift from transient to permanent kleptoplasty. Symbiosis 2012, 58, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowbridge, C.D.; Todd, C.D. Host-plant change in marine specialist herbivores: Ascoglossan sea slugs on introduced macroalgae. Ecol. Monogr. 2001, 71, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenbach, S.; Melo Clavijo, J.; Brück, M.; Bleidißel, S.; Simon, M.; Gasparoni, G.; Lo Porto, C.; Laetz, E.M.J.; Greve, C.; Donath, A.; et al. Shedding light on starvation in darkness in the plastid-bearing sea slug Elysia viridis (Montagu, 1804). Mar. Biol. 2023, 170, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laetz, E.M.J.; Kahyaoglu, C.; Borgstein, N.M.; Merkx, M.; van der Meij, S.E.T.; Verberk, W.C.E.P. Critical thermal maxima and oxygen uptake in Elysia viridis, a sea slug that steals chloroplasts to photosynthesize. J. Exp. Biol. 2024, 227, jeb246331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujer, C.V.; Andrews, D.L.; Manhart, J.R.; Pierce, S.K.; Rumpho, M.E. Chloroplast genes are expressed during intracellular symbiotic association of Vaucheria litorea plastids with the sea slug Elysia chlorotica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 12333–12338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpho, M.E.; Worful, J.M.; Lee, J.; Kannan, K.; Tyler, M.S.; Bhattacharya, D.; Moustafa, A.; Manhart, J.R. Horizontal gene transfer of the algal nuclear gene psbO to the photosynthetic sea slug Elysia chlorotica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17867–17871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, S.K.; Mahadevan, P.; Massey, S.E.; Middlebrooks, M.L. A preliminary molecular and phylogenetic analysis of the genome of a novel endogenous retrovirus in the sea slug Elysia chlorotica. Biol. Bull. 2016, 231, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, L.J.; Middlebrooks, M.L.; Schlegel, S.A.; Curtis, N.E.; Pierce, S.K. The unexpected presence of Elysia chlorotica (Gould, 1870) in Tampa Bay, Florida, U.S.A. with notes on seasonal population decline. Am. Malacol. Bull. 2025, 42, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Männer, L.; Schell, T.; Spies, J.; Galià-Camps, C.; Baranski, D.; Hamadou, A.B.; Gerheim, C.; Neveling, K.; Helfrich, E.J.N.; Greve, C. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the sacoglossan sea slug Elysia timida (Risso, 1818). BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havurinne, V.; Tyystjärvi, E. Photosynthetic sea slugs induce protective changes to the light reactions of the chloroplasts they steal from algae. eLife 2020, 9, e57389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Takahashi, S.; Yoshida, T.; Shimamura, S.; Takaki, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Toyoda, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Arimoto, A.; Ishii, H.; et al. Chloroplast acquisition without the gene transfer in kleptoplastic sea slugs, Plakobranchus ocellatus. eLife 2021, 10, e60176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumais, J.; Harrison, L.G. Whorl morphogenesis in the dasycladalean algae: The pattern formation viewpoint. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 2000, 355, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, G.J.; Kohler, S.; Collins, J.-J.; Richir, J.; Arduini, D.; Calabrese, C.; Schaefer, M. Can the global marine aquarium trade (MAT) be a model for sustainable coral reef fisheries? Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondo, M.V.; Burki, R.P.; Aguayo, F.; Calado, R. An updated review of the marine ornamental fish trade in the European Union. Animals 2024, 14, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmtag, M.R. The marine ornamental species trade. In Marine Ornamental Species Aquaculture; Calado, R., Olivotto, I., Oliver, M.P., Holt, G.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Olivotto, I.; Planas, M.; Simões, N.; Holt, G.J.; Avella, M.A.; Calado, R. Advances in breeding and rearing marine ornamentals. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2011, 42, 135–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, R.; Olivotto, I.; Oliver, M.P.; Holt, G.J. Marine ornamental invertebrates aquaculture. In Marine Ornamental Species Aquaculture; Calado, R., Olivotto, I., Oliver, M.P., Holt, G.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 381–383. [Google Scholar]

- Calfo, A.R.; Fenner, R. Reef Invertebrates: An Essential Guide to Selection, Care and Compatibility; Reading Trees: Monroeville, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cartaxana, P.; Lopes, D.; Havurinne, V.; Silva, M.I.; Calado, R.; Cruz, S. Laboratory Rearing of the Photosynthetic Sea Slug Elysia crispata (Gastropoda, Sacoglossa): Implications for the Study of Kleptoplasty and Species Conservation. Biology 2026, 15, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020168

Cartaxana P, Lopes D, Havurinne V, Silva MI, Calado R, Cruz S. Laboratory Rearing of the Photosynthetic Sea Slug Elysia crispata (Gastropoda, Sacoglossa): Implications for the Study of Kleptoplasty and Species Conservation. Biology. 2026; 15(2):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020168

Chicago/Turabian StyleCartaxana, Paulo, Diana Lopes, Vesa Havurinne, Maria I. Silva, Ricardo Calado, and Sónia Cruz. 2026. "Laboratory Rearing of the Photosynthetic Sea Slug Elysia crispata (Gastropoda, Sacoglossa): Implications for the Study of Kleptoplasty and Species Conservation" Biology 15, no. 2: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020168

APA StyleCartaxana, P., Lopes, D., Havurinne, V., Silva, M. I., Calado, R., & Cruz, S. (2026). Laboratory Rearing of the Photosynthetic Sea Slug Elysia crispata (Gastropoda, Sacoglossa): Implications for the Study of Kleptoplasty and Species Conservation. Biology, 15(2), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020168