Oxidative-Stress-Mediated AMPK/mTOR Signaling in Bovine Mastitis: An Integrative Analysis Combining 16S rDNA Sequencing and Molecular Pathology

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Main Materials

2.2. Main Reagents

2.3. Main Instruments

2.4. Experimental Methods

2.4.1. Collection and Fixation of Materials

2.4.2. Bacterial Isolation and Identification

2.4.3. H&E Staining Procedures

2.4.4. Immunohistochemical Experiment Procedures

2.4.5. Total RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription Ploymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) Analysis

2.4.6. Western Blot

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial Isolation, Cultivation, and Strain Identification

3.2. H&E Staining

3.3. Immunohistochemistry

3.4. Expression Levels of Oxidative Stress-Related Genes in Bovine Mammary Tissue

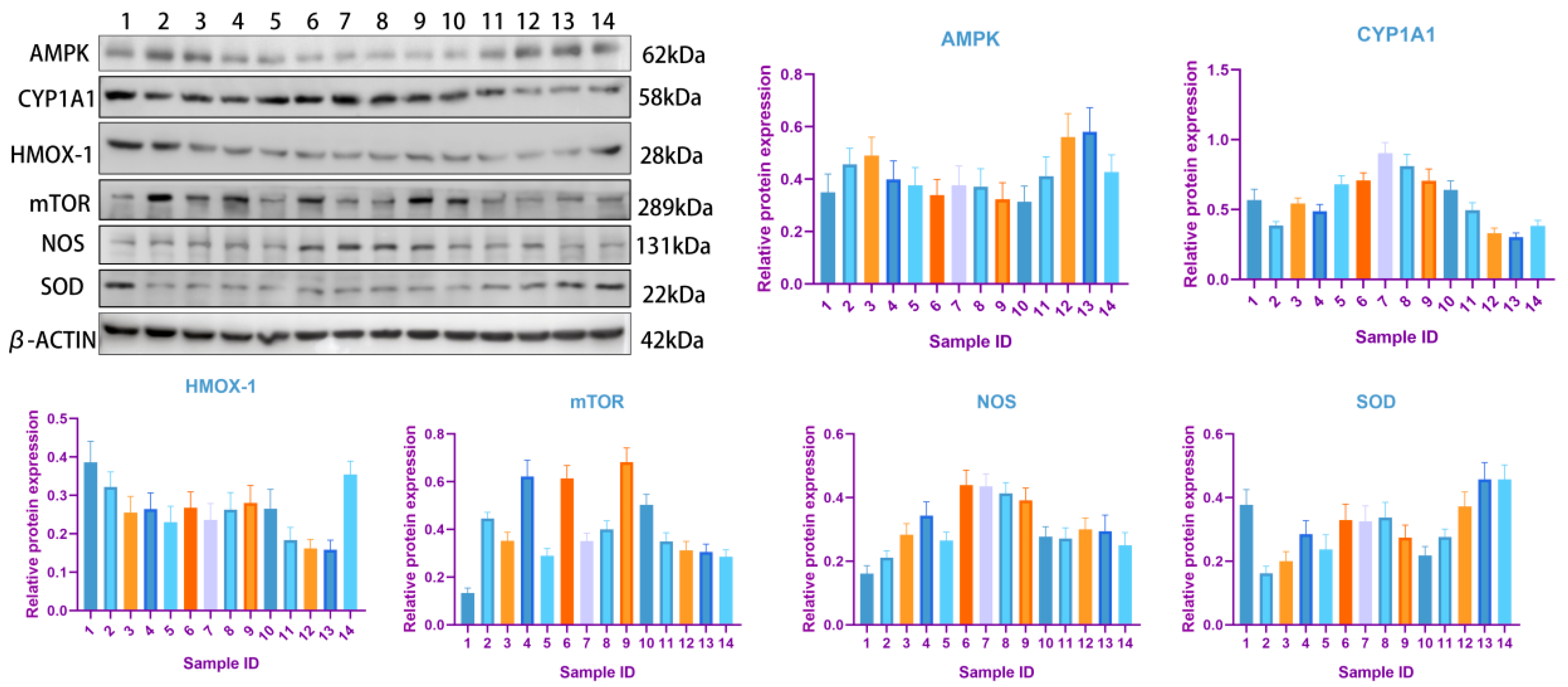

3.5. Western Blot

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| NOX | NADPH oxidases |

| NAC | N-carbamylglutamate |

| EDTA | Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid |

| DAB | Diaminobenzidine |

| AMPK | Adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase |

| CYP1A1 | Cytochrome P450 1A1 |

| HMOX-1 | Heme oxygenase 1 |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| NOS | Nitric oxide synthase |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

References

- Bates, A.J.; King, C.; Dhar, M.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Laven, R.A. Retention of Internal Teat Sealants over the Dry Period and Their Efficacy in Reducing Clinical and Subclinical Mastitis at Calving. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 5449–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Santos, R.; González-Revello, Á.; Majul, L.; Umpiérrez, A.; Aldrovandi, A.; Gil, A.; Hirigoyen, D.; Zunino, P. Subclinical Bovine Mastitis Associated with Staphylococcus Spp. in Eleven Uruguayan Dairy Farms. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 16, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubia, K.M.; Akter, A.; Carter, B.H.; McDaniel, M.R.; Duff, G.C.; Löest, C.A. Effects of Supplementing Milk Replacer with Essential Amino Acids on Blood Metabolites, Immune Response, and Nitrogen Metabolism of Holstein Calves Exposed to an Endotoxin. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 5402–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, F.D.; Neathery, M.W.; Gentry, R.P.; Miller, W.J.; Logner, K.R.; Blackmon, D.M. The Effects of Different Levels of Dietary Lead on Zinc Metabolism in Dairy Calves. J. Dairy Sci. 1985, 68, 1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-P.; Hu, Q.-C.; Yang, J.; Luoreng, Z.-M.; Wang, X.-P.; Ma, Y.; Wei, D.-W. Differential Expression Profiles of lncRNA Following LPS-Induced Inflammation in Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 758488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Lee, C.; Kim, I.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Yun, T.; Hooper, D.C.; Walker, S.; Lee, W. Environmental Cues in Different Host Niches Shape the Survival Fitness of Staphylococcus Aureus. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezina, B.; Al-Harbi, H.; Ramay, H.R.; Soust, M.; Moore, R.J.; Olchowy, T.W.J.; Alawneh, J.I. Sequence Characterisation and Novel Insights into Bovine Mastitis-Associated Streptococcus Uberis in Dairy Herds. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakr, A.; Brégeon, F.; Mège, J.-L.; Rolain, J.-M.; Blin, O. Staphylococcus Aureus Nasal Colonization: An Update on Mechanisms, Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Subsequent Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnyder, P.; Schönecker, L.; Schüpbach-Regula, G.; Meylan, M. Animal Transport and Barn Climate on Animal Health and Antimicrobial Use in Swiss Veal Calf Operations. Prev. Vet. Med. 2019, 167, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Li, Q.; Liao, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z. Enhancing Agricultural Productivity in Dairy Cow Mastitis Management: Innovations in Non-Antibiotic Treatment Technologies. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkel, T.; Holbrook, N.J. Oxidants, Oxidative Stress and the Biology of Ageing. Nature 2000, 408, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, B.; Kwakye, J.; Ariyo, O.W.; Ghareeb, A.F.A.; Milfort, M.C.; Fuller, A.L.; Khatiwada, S.; Rekaya, R.; Aggrey, S.E. Major Oxidative and Antioxidant Mechanisms During Heat Stress-Induced Oxidative Stress in Chickens. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunnill, C.; Patton, T.; Brennan, J.; Barrett, J.; Dryden, M.; Cooke, J.; Leaper, D.; Georgopoulos, N.T. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Wound Healing: The Functional Role of ROS and Emerging ROS-Modulating Technologies for Augmentation of the Healing Process. Int. Wound J. 2017, 14, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douda, D.N.; Khan, M.A.; Grasemann, H.; Palaniyar, N. SK3 Channel and Mitochondrial ROS Mediate NADPH Oxidase-Independent NETosis Induced by Calcium Influx. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2817–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Gao, W.; Wang, Z.; Jian, H.; Peng, L.; Yu, X.; Xue, P.; Peng, W.; Li, K.; Zeng, P. Polyphyllin I Induced Ferroptosis to Suppress the Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma through Activation of the Mitochondrial Dysfunction via Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 Axis. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2024, 122, 155135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.X. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Cardiovascular Disorders. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2012, 12, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several Lines of Antioxidant Defense against Oxidative Stress: Antioxidant Enzymes, Nanomaterials with Multiple Enzyme-Mimicking Activities, and Low-Molecular-Weight Antioxidants. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachut, M.; Contreras, G.A. Symposium Review: Mechanistic Insights into Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Periparturient Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 3670–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feniouk, B.A.; Skulachev, V.P. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants. Curr. Aging Sci. 2017, 10, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Liang, Y.; Coleman, D.N.; Li, Y.; Ding, H.; Liu, F.; Cardoso, F.F.; Parys, C.; Cardoso, F.C.; Shen, X.; et al. Methionine Supplementation during a Hydrogen Peroxide Challenge Alters Components of Insulin Signaling and Antioxidant Proteins in Subcutaneous Adipose Explants from Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Huo, R.; Wang, Y.; Ma, N.; Shi, X.; Shen, X.; Chang, G. Lentinan Inhibits Oxidative Stress and Alleviates LPS-Induced Inflammation and Apoptosis of BMECs by Activating the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 2375–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duse, A.; Persson-Waller, K.; Pedersen, K. Microbial Aetiology, Antibiotic Susceptibility and Pathogen-Specific Risk Factors for Udder Pathogens from Clinical Mastitis in Dairy Cows. Animals 2021, 11, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, A.-M.; Liski, E.; Pyörälä, S.; Taponen, S. Pathogen-Specific Production Losses in Bovine Mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 9493–9504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoš, O.; Chmel, M.; Swierczková, I. The Overlooked Evolutionary Dynamics of 16S rRNA Revises Its Role as the “Gold Standard” for Bacterial Species Identification. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Teng, J.L.L.; Tse, H.; Yuen, K.-Y. Then and Now: Use of 16S rDNA Gene Sequencing for Bacterial Identification and Discovery of Novel Bacteria in Clinical Microbiology Laboratories. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 908–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racsa, L.D.; DeLeon-Carnes, M.; Hiskey, M.; Guarner, J. Identification of Bacterial Pathogens from Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Tissues by Using 16S Sequencing: Retrospective Correlation of Results to Clinicians’ Responses. Hum. Pathol. 2017, 59, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-M.; Park, J.-E.; Park, J.-S.; Leem, Y.-H.; Kim, D.-Y.; Hyun, J.-W.; Kim, H.-S. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Mechanisms of Coniferaldehyde in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation: Involvement of AMPK/Nrf2 and TAK1/MAPK/NF-κB Signaling Pathways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 979, 176850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, J.S.; Son, S.; Park, S.; Oh, H.; Choi, Y.K.; Kim, D.-E. AMPK Activation Mitigates α-Synuclein Pathology and Dopaminergic Degeneration in Cellular and Mouse Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Neuropharmacology 2025, 281, 110700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, R.; Kumar, S. Mfn2-Mediated Mitochondrial Fusion Promotes Autophagy and Suppresses Ovarian Cancer Progression by Reducing ROS through AMPK/mTOR/ERK Signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, G.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Y. Unraveling the AMPK-SIRT1-FOXO Pathway: The In-Depth Analysis and Breakthrough Prospects of Oxidative Stress-Induced Diseases. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 70. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/14/1/70 (accessed on 18 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Guan, Q.; Tian, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, P. Maintenance of Airway Epithelial Barrier Integrity via the Inhibition of AHR/EGFR Activation Ameliorates Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Using Effective-Component Combination. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2023, 118, 154980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Annalora, A.J.; Murray, I.A.; Tian, Y.; Marcus, C.B.; Patterson, A.D.; Perdew, G.H. Endogenous Tryptophan-Derived Ah Receptor Ligands Are Dissociated from CYP1A1/1B1-Dependent Negative-Feedback. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2023, 16, 11786469231182508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahrer, J.; Wittmann, S.; Wolf, A.-C.; Kostka, T. Heme Oxygenase-1 and Its Role in Colorectal Cancer. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zeng, L.; Cai, L.; Zheng, W.; Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Jin, X.; Bai, Y.; Lai, M.; Li, H.; et al. Cellular Senescence-Associated Gene IFI16 Promotes HMOX1-Dependent Evasion of Ferroptosis and Radioresistance in Glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Choi, T.G.; Park, S.; Yun, H.R.; Nguyen, N.N.Y.; Jo, Y.H.; Jang, M.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kang, I.; et al. Mitochondrial ROS-Derived PTEN Oxidation Activates PI3K Pathway for mTOR-Induced Myogenic Autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 1921–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, A.; Rizvi, S.F.; Parveen, S.; Pathak, N.; Nazir, A.; Mir, S.S. Crosstalk Between ROS and Autophagy in Tumorigenesis: Understanding the Multifaceted Paradox. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 852424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.; Lee, J.; Seo, S.; Uddin, S.; Lee, S.; Han, S.B.; Cho, S. Regulation of Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Responses by Methanol Extract of Mikania Cordata (Burm. f.) B. L. Rob. Leaves via the Inactivation of NF-κB and MAPK Signaling Pathways and Activation of Nrf2 in LPS-Induced RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Liu, J.; Fan, P.; Dong, X.; Zhu, K.; Liu, X.; Zhang, N.; Cao, Y. Dioscin Prevents DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice with Enhancing Intestinal Barrier Function and Reducing Colon Inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 99, 108015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Yin, J.; Xia, S.; Jiang, Y.; Ge, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Hou, Z.; Bai, Y.; et al. Biomineralized ZIF-8 Encapsulating SOD from Hydrogenobacter Thermophilus: Maintaining Activity in the Intestine and Alleviating Intestinal Oxidative Stress. Small 2024, 20, 2402812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.M.; Edeas, M.A. SOD, Oxidative Stress and Human Pathologies: A Brief History and a Future Vision. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2005, 59, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) | TM (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| AMPK | F: GTGGTGACCCTCAAGACCAG | 58.3 |

| R: TTCCGGATGAGGTTTCAGG | ||

| CYP1A1 | F: TGCAGGAGAACATCCCTACC | 56.7 |

| R: GGTAGGGTGATGAGGTCCAC | ||

| HMOX-1 | F: CTGACAGCATGCCCCAGGAT | 55.1 |

| R: CTTCTCCTGGGCTCTCTCCT | ||

| NOS | F: CCCCAGACAGCTTCTACCT | 55.5 |

| R: TCCTTTGTTACTGCTTCACC | ||

| mTOR | F: TGCGGTCACTCGTCGTCAG | 60.6 |

| R: TGCCAGCCTGCCACTCTTG | ||

| SOD | F: ATCCACTTCGAGGCAAAGGG | 57.8 |

| R: GTGAGGACCTGCACTGGTAC | ||

| β-actin | F: TCTGGCACCACACCTTCTACAAC | 60.1 |

| R: GGACAGCACAGCCTGGAT |

| Sample ID | The Isolated Bacterial Strain |

|---|---|

| 1 | Escherichia coli |

| 2 | Escherichia coli |

| 3 | Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter johnsonii |

| 4 | Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas, and Aeromonas |

| 5 | Escherichia coli, Aeromonas |

| 6 | Pseudomonas peli, Comamonas |

| 7 | Escherichia coli, Aeromonas salmonicida |

| 8 | Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas |

| 9 | Bacillus licheniformis |

| 10 | Aeromonas |

| 11 | Pseudomonas guangdongensis, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, and Mammaliicoccus sciuri |

| 12 | No bacterial strain was isolated. |

| 13 | Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| Names of Images | Positive Cells, % | Positive Cell Density, Number/mm2 | Mean Density | H-Score | IRS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMPK-1 | 80.55% | 3067 | 0.1952 | 178.60 | 8 |

| AMPK-2 | 55.17% | 1307 | 0.1497 | 119.70 | 6 |

| AMPK-3 | 83.54% | 4977 | 0.2367 | 197.31 | 8 |

| AMPK-4 | 79.27% | 2995 | 0.2021 | 224.25 | 12 |

| AMPK-5 | 83.43% | 4215 | 0.2288 | 201.31 | 8 |

| AMPK-6 | 73.92% | 2591 | 0.2165 | 177.22 | 6 |

| AMPK-7 | 79.90% | 3252 | 0.1968 | 210.62 | 12 |

| AMPK-8 | 23.88% | 1334 | 0.1371 | 38.29 | 2 |

| AMPK-9 | 84.33% | 2555 | 0.2247 | 235.32 | 12 |

| AMPK-10 | 79.80% | 2040 | 0.2078 | 195.57 | 8 |

| AMPK-11 | 80.35% | 2463 | 0.1995 | 174.91 | 8 |

| AMPK-12 | 87.46% | 2859 | 0.2050 | 225.00 | 12 |

| AMPK-13 | 43.83% | 1971 | 0.1665 | 78.18 | 4 |

| AMPK-14 | - | - | - | - | - |

| CYP1A1-1 | 95.86% | 3076 | 0.1469 | 226.46 | 8 |

| CYP1A1-2 | 93.07% | 2044 | 0.1288 | 204.69 | 8 |

| CYP1A1-3 | 91.94% | 4859 | 0.2234 | 213.57 | 8 |

| CYP1A1-4 | 94.07% | 3084 | 0.1997 | 262.39 | 12 |

| CYP1A1-5 | 96.97% | 2443 | 0.1618 | 233.43 | 8 |

| CYP1A1-6 | 96.03% | 2739 | 0.1786 | 255.50 | 12 |

| CYP1A1-7 | 87.65% | 1873 | 0.1522 | 178.19 | 8 |

| CYP1A1-8 | 95.59% | 3311 | 0.2042 | 213.55 | 8 |

| CYP1A1-9 | 94.28% | 2516 | 0.1560 | 209.63 | 8 |

| CYP1A1-10 | 95.47% | 3589 | 0.1780 | 248.64 | 12 |

| CYP1A1-11 | 96.06% | 2671 | 0.1883 | 247.85 | 12 |

| CYP1A1-12 | 93.45% | 2902 | 0.2290 | 236.74 | 12 |

| CYP1A1-13 | 92.12% | 2829 | 0.2066 | 207.36 | 8 |

| CYP1A1-14 | - | - | - | - | - |

| HMOX-1-1 | 37.18% | 1913 | 0.2546 | 87.93 | 4 |

| HMOX-1-2 | 23.34% | 698 | 0.1912 | 54.75 | 2 |

| HMOX-1-3 | 47.50% | 3302 | 0.2406 | 107.09 | 4 |

| HMOX-1-4 | 35.80% | 1807 | 0.1771 | 73.54 | 4 |

| HMOX-1-5 | 32.57% | 2557 | 0.2378 | 74.41 | 4 |

| HMOX-1-6 | 31.38% | 1538 | 0.2520 | 71.25 | 4 |

| HMOX-1-7 | 74.04% | 3437 | 0.2038 | 169.70 | 6 |

| HMOX-1-8 | 11.94% | 707 | 0.2539 | 28.47 | 2 |

| HMOX-1-9 | 47.43% | 2266 | 0.2407 | 107.54 | 4 |

| HMOX-1-10 | 56.96% | 1965 | 0.2394 | 131.58 | 6 |

| HMOX-1-11 | 39.07% | 1663 | 0.2617 | 93.90 | 4 |

| HMOX-1-12 | 51.78% | 2510 | 0.2535 | 123.50 | 6 |

| HMOX-1-13 | 10.04% | 474 | 0.3138 | 25.85 | 3 |

| HMOX-1-14 | - | - | - | - | - |

| mTOR-1 | 59.81% | 2994 | 0.1493 | 118.68 | 6 |

| mTOR-2 | 19.27% | 523 | 0.1825 | 42.66 | 2 |

| mTOR-3 | 42.43% | 2559 | 0.1746 | 81.90 | 4 |

| mTOR-4 | 75.82% | 3046 | 0.1223 | 154.01 | 8 |

| mTOR-5 | 39.57% | 2476 | 0.1914 | 79.76 | 4 |

| mTOR-6 | 61.65% | 3367 | 0.1548 | 126.38 | 6 |

| mTOR-7 | 41.79% | 2814 | 0.1572 | 80.34 | 4 |

| mTOR-8 | 44.49% | 2286 | 0.1441 | 78.97 | 4 |

| mTOR-9 | 61.45% | 2926 | 0.1657 | 123.15 | 6 |

| mTOR-10 | 63.16% | 3225 | 0.1515 | 129.79 | 6 |

| mTOR-11 | 42.93% | 1751 | 0.1598 | 82.92 | 4 |

| mTOR-12 | 74.41% | 3611 | 0.1560 | 152.67 | 6 |

| mTOR-13 | 48.77% | 2005 | 0.1557 | 89.94 | 4 |

| mTOR-14 | - | - | - | - | - |

| NOS-1 | 30.39% | 885 | 0.1978 | 54.60 | 4 |

| NOS-2 | 20.77% | 407 | 0.1568 | 35.29 | 2 |

| NOS-3 | 35.03% | 1288 | 0.1886 | 64.11 | 4 |

| NOS-4 | 54.77% | 976 | 0.1460 | 92.97 | 6 |

| NOS-5 | 29.48% | 909 | 0.1774 | 53.04 | 4 |

| NOS-6 | 7.50% | 187 | 0.1948 | 12.23 | 2 |

| NOS-7 | 33.89% | 487 | 0.1642 | 55.47 | 4 |

| NOS-8 | 22.56% | 1253 | 0.1441 | 35.43 | 2 |

| NOS-9 | 33.21% | 766 | 0.1953 | 60.18 | 4 |

| NOS-10 | 43.85% | 1174 | 0.2068 | 86.80 | 4 |

| NOS-11 | 36.71% | 987 | 0.1610 | 64.05 | 4 |

| NOS-12 | 35.29% | 936 | 0.1437 | 61.00 | 4 |

| NOS-13 | 0.60% | 30 | 0.2632 | 1.14 | 0 |

| NOS-14 | - | - | - | - | - |

| SOD-1 | 87.33% | 2021 | 0.2091 | 220.91 | 12 |

| SOD-2 | 95.33% | 1523 | 0.2048 | 267.15 | 12 |

| SOD-3 | 75.06% | 2308 | 0.2074 | 151.74 | 8 |

| SOD-4 | 81.21% | 2404 | 0.1452 | 180.02 | 8 |

| SOD-5 | 69.61% | 1618 | 0.2034 | 145.39 | 6 |

| SOD-6 | 58.45% | 1211 | 0.1862 | 115.29 | 6 |

| SOD-7 | 78.31% | 2366 | 0.1694 | 171.88 | 8 |

| SOD-8 | 22.08% | 1214 | 0.1801 | 40.35 | 2 |

| SOD-9 | 86.98% | 1244 | 0.1951 | 192.10 | 8 |

| SOD-10 | 71.89% | 1572 | 0.2084 | 163.67 | 6 |

| SOD-11 | 73.85% | 1884 | 0.1845 | 153.02 | 6 |

| SOD-12 | 90.66% | 1256 | 0.1836 | 201.02 | 8 |

| SOD-13 | 24.80% | 1137 | 0.1878 | 48.66 | 2 |

| SOD-14 | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, D.; Zhao, F.; Jia, L.; Sun, Z.; Cao, G.; Zhang, Y. Oxidative-Stress-Mediated AMPK/mTOR Signaling in Bovine Mastitis: An Integrative Analysis Combining 16S rDNA Sequencing and Molecular Pathology. Biology 2026, 15, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020115

Zhang Y, Zhang M, Wang D, Zhao F, Jia L, Sun Z, Cao G, Zhang Y. Oxidative-Stress-Mediated AMPK/mTOR Signaling in Bovine Mastitis: An Integrative Analysis Combining 16S rDNA Sequencing and Molecular Pathology. Biology. 2026; 15(2):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020115

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuanyuan, Min Zhang, Daqing Wang, Feifei Zhao, Luofei Jia, Zhiwei Sun, Guifang Cao, and Yong Zhang. 2026. "Oxidative-Stress-Mediated AMPK/mTOR Signaling in Bovine Mastitis: An Integrative Analysis Combining 16S rDNA Sequencing and Molecular Pathology" Biology 15, no. 2: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020115

APA StyleZhang, Y., Zhang, M., Wang, D., Zhao, F., Jia, L., Sun, Z., Cao, G., & Zhang, Y. (2026). Oxidative-Stress-Mediated AMPK/mTOR Signaling in Bovine Mastitis: An Integrative Analysis Combining 16S rDNA Sequencing and Molecular Pathology. Biology, 15(2), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020115