Do Symbiotic Microbes Drive Chemical Divergence Between Colonies in the Pratt’s Leaf-Nosed Bat, Hipposideros pratti?

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Sampling

2.2. Forehead Gland Secretion Collection and Chemical Compound Analysis

2.3. Bacterial DNA Extraction, Processing and Sequencing

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Scent Profiles and Colony-Specific Scent Profile

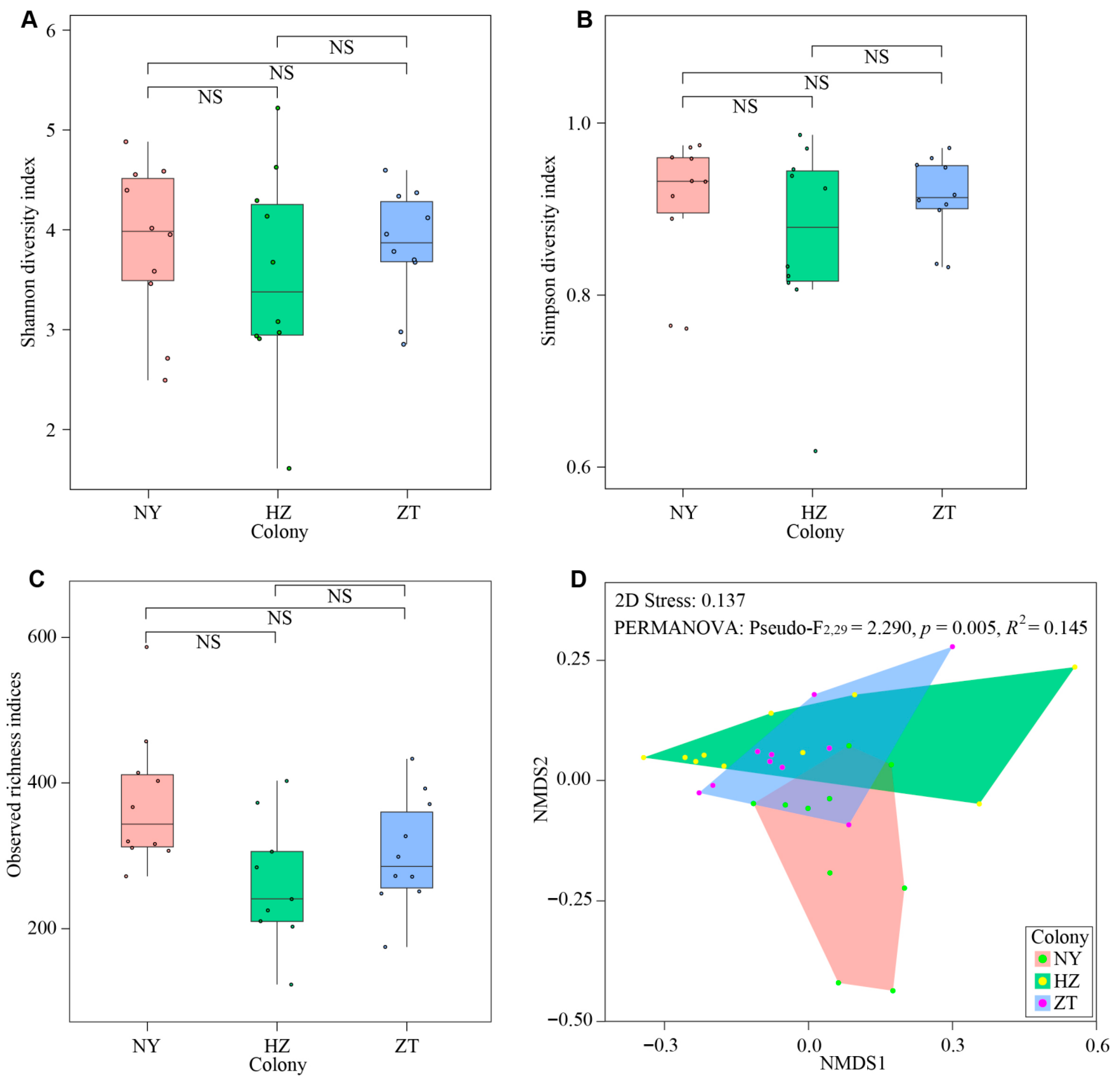

3.2. Variation in the Gland Microbiota Across Colonies

3.3. Relationships Between the Gland Microbiota and Chemical Composition

4. Discussion

4.1. Variation in Chemical Signals

4.2. Variation in Gland Microbiota

4.3. What Drives Variation in Chemical Signals?

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NY | Nanyang |

| HZ | Hanzhong |

| ZT | Zhaotong |

| GC-MS | gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| NMDS | nonmetric multidimensional scaling |

| ANOSIM | nonparametric analysis of similarity |

References

- Wyatt, T.D. Pheromones and Animal Behaviour; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smadja, C.; Ganem, G. Subspecies recognition in the house mouse: A study of two populations from the border of a hybrid zone. Behav. Ecol. 2002, 13, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeckens, S.; Martín, J.; García-Roa, R.; Pafilis, P.; Huyghe, K.; Damme, R.V. Environmental conditions shape the chemical signal design of lizards. Funct. Ecol. 2018, 32, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean, E.F.; Bruford, M.W.; Russo, I.M.; Müller, C.T.; Chadwick, E.A. Odour dialects among wild mammals. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albone, E.S.; Perry, G.C. Anal sac secretion of the red fox, Vulpes vulpes; volatile fatty acids and diamines: Implications for a fermentation hypothesis of chemical recognition. J. Chem. Ecol. 1976, 2, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, M.L. A mechanism for individual recognition by odour in Herpestes auropunctatus (Carnivora: Viverridae). Anim. Behav. 1976, 24, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, N.J.; Mant, J.; Schiestl, E.P. Population differentiation in female sex pheromone and male preferences in a solitary bee. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2007, 61, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya-García, E.; Suazo-Ortuño, I.; Campos-García, J.; Martín, J.; Alvarado-Díaz, J.; Mendoza-Ramírez, E. Chemical signal divergence among populations influences behavioral discrimination in the whiptail lizard Aspidoscelis lineattissimus (squamata: Teiidae). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2020, 74, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, L.A.; Gloor, G.B.; Kelly, T.R.; Bernards, M.A.; MacDougall-Shackleton, E. A Preen gland microbiota of songbirds differ across populations but not sexes. J. Anim. Ecol. 2021, 90, 2202–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebbe, J.; Humble, E.; Stoffel, M.A.; Tewes, L.J.; Müller, C.; Forcada, J.; Caspers, B.; Hoffman, J.I. Chemical patterns of colony membership and mother-offspring similarity in Antarctic fur seals are reproducible. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, E.H.; Fenton, M.B. Role of acoustic social communication in the lives of bats. In Bat Bioacoustics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 117–139. [Google Scholar]

- Chaverri, G.; Ancillotto, L.; Russo, D. Social communication in bats. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 1938–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Romo, M.; Page, R.A.; Kunz, T.H. Redefining the study of sexual dimorphism in bats: Following the odour trail. Mammal Rev. 2021, 51, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, K.; Kerth, G. Secretions of the interaural gland contain information about individuality and colony membership in the Bechstein’s bat. Anim. Behav. 2003, 65, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneeberger, K.; Voigt, C.C.; Müller, C.; Caspers, B.A. Multidimensionality of chemical information in male greater sac-winged bats (Saccopteryx bilineata). Front. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 4, 207847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloss, J.; Acree, T.E.; Bloss, J.M.; Hood, W.R.; Kunz, T.H. Potential use of chemical cues for colony-mate recognition in the big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus. J. Chem. Ecol. 2002, 28, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Lucas, J.R.; Zhuang, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, D. Male forehead gland scent may encode multiple information in the great Himalayan leaf-nosed bat, Hipposideros armiger. Anim. Behav. 2025, 225, 123227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, T.; Wohlgemuth, G.; Lee, D.Y.; Lu, Y.; Palazoglu, M.; Shahbaz, S.; Fiehn, O. FiehnLib: Mass spectral and retention index libraries for metabolomics based on quadrupole and time-of-flight gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 10038–10048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Gonzalez Peña, A.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, D.; Price, M.N.; Goodrich, J.; Nawrocki, E.P.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Probst, A.; Andersen, G.L.; Knight, R.; Hugenholtz, P. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 2012, 6, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Subramanian, S.; Faith, J.J.; Gevers, D.; Gordon, J.I.; Knight, R.; Mills, D.A.; Caporaso, J.G. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M. Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation; Plymouth Marine Laboratory: Plymouth, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, P.; Palmer, M.W. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 2003, 14, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J. Package ‘Vegan’. 2015. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Hochberg, Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 1988, 75, 800–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F.E., Jr.; Dupont, C. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous, R Package Version 4.4-0; 2020. Available online: https://github.com/harrelfe/Hmisc (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Antonov, M.; Csárdi, G.; Horvát, S.; Müller, K.; Nepusz, T.; Noom, D.; Salmon, M.; Traag, V.; Welles, B.F.; Zanini, F. igraph enables fast and robust network analysis across programming languages. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.10260v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Development Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sokal, R.R.; Rohlf, F.J. Biometry: The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research, 3rd ed.; Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nottebohm, F. The song of the chingolo, Zonotrichia capensis, in Argentina: Description and evaluation of a system of dialects. Condor 1969, 71, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Hao, Y.; Song, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; He, J.; Bu, Y.; Niu, H. Molecular phylogeography of Hipposideros pratti in China. Integr. Zool. 2024, 19, 999–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustin, M.K.; McCracken, G.F. Scent recognition between females and pups in the bat Tadarida brasiliensis mexicana. Anim. Behav. 1987, 35, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ydenberg, R.C.; Giraldeau, L.A.; Falls, J.B. Neighbours, strangers, and the asymmetric war of attrition. Anim. Behav. 1988, 36, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temeles, E.J. The role of neighbours in territorial systems: When are they ’dear enemies’? Anim. Behav. 1994, 47, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux-Labonté, V.; Simard, A.; Willis, C.K.R.; Lapointe, F.J. Enrichment of beneficial bacteria in the skin microbiota of bats persisting with white-nose syndrome. Microbiome 2017, 5, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coux, C.; Rader, R.; Bartomeus, I.; Tylianakis, J.M. Linking species functional roles to their network roles. Ecol. Lett. 2016, 19, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theis, K.R.; Schmidt, T.M.; Holekamp, K.E. Evidence for a bacterial mechanism for group-specific social odors among hyenas. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theis, K.R.; Venkataraman, A.; Dycus, J.A.; Koonter, K.D.; Koonter, E.N.; Wagner, A.P.; Holekamp, K.E.; Schmidt, T.M. Symbiotic bacteria appear to mediate hyena social odors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19832–19837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Colony | Mean Number of Compounds per Individual ± SE * | Total Number of Compounds Occurring in All Samples from the Colony | Number of Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanyang (NY) | 41.70 ± 2.69 | 9 | 10 |

| Hanzhong (HZ) | 37.50 ± 1.45 | 17 | 10 |

| Zhaotong (ZT) | 39.00 ± 1.45 | 16 | 10 |

| Alcohol | Aldehyde | Alkane | Alkene | Aromatic Compound | Carboxylic Acid | Ester | Ketone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-individual CV (%; NY) | 66.3 | 51.7 | 102.4 | 202.7 | 49.3 | 79.0 | 83.6 | 56.4 |

| Inter-individual CV (%; SX) | 38.0 | 92.5 | 74.7 | 68.2 | 31.0 | 94.7 | 96.7 | 88.0 |

| Inter-individual CV (%; ZT) | 72.8 | 60.2 | 64.4 | 215.8 | 37.0 | 70.1 | 55.5 | 68.6 |

| Inter-colonial CV (%) | 25.4 | 110.2 | 48.6 | 66.0 | 51.3 | 79.7 | 98.9 | 31.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zheng, Z.; Lucas, J.R.; Zhang, C.; Sun, C. Do Symbiotic Microbes Drive Chemical Divergence Between Colonies in the Pratt’s Leaf-Nosed Bat, Hipposideros pratti? Biology 2026, 15, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020114

Zheng Z, Lucas JR, Zhang C, Sun C. Do Symbiotic Microbes Drive Chemical Divergence Between Colonies in the Pratt’s Leaf-Nosed Bat, Hipposideros pratti? Biology. 2026; 15(2):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020114

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Ziqi, Jeffrey R. Lucas, Chunmian Zhang, and Congnan Sun. 2026. "Do Symbiotic Microbes Drive Chemical Divergence Between Colonies in the Pratt’s Leaf-Nosed Bat, Hipposideros pratti?" Biology 15, no. 2: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020114

APA StyleZheng, Z., Lucas, J. R., Zhang, C., & Sun, C. (2026). Do Symbiotic Microbes Drive Chemical Divergence Between Colonies in the Pratt’s Leaf-Nosed Bat, Hipposideros pratti? Biology, 15(2), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020114