Deciphering the Origins of Commercial Sweetpotato Genotypes Using International Genebank Data

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

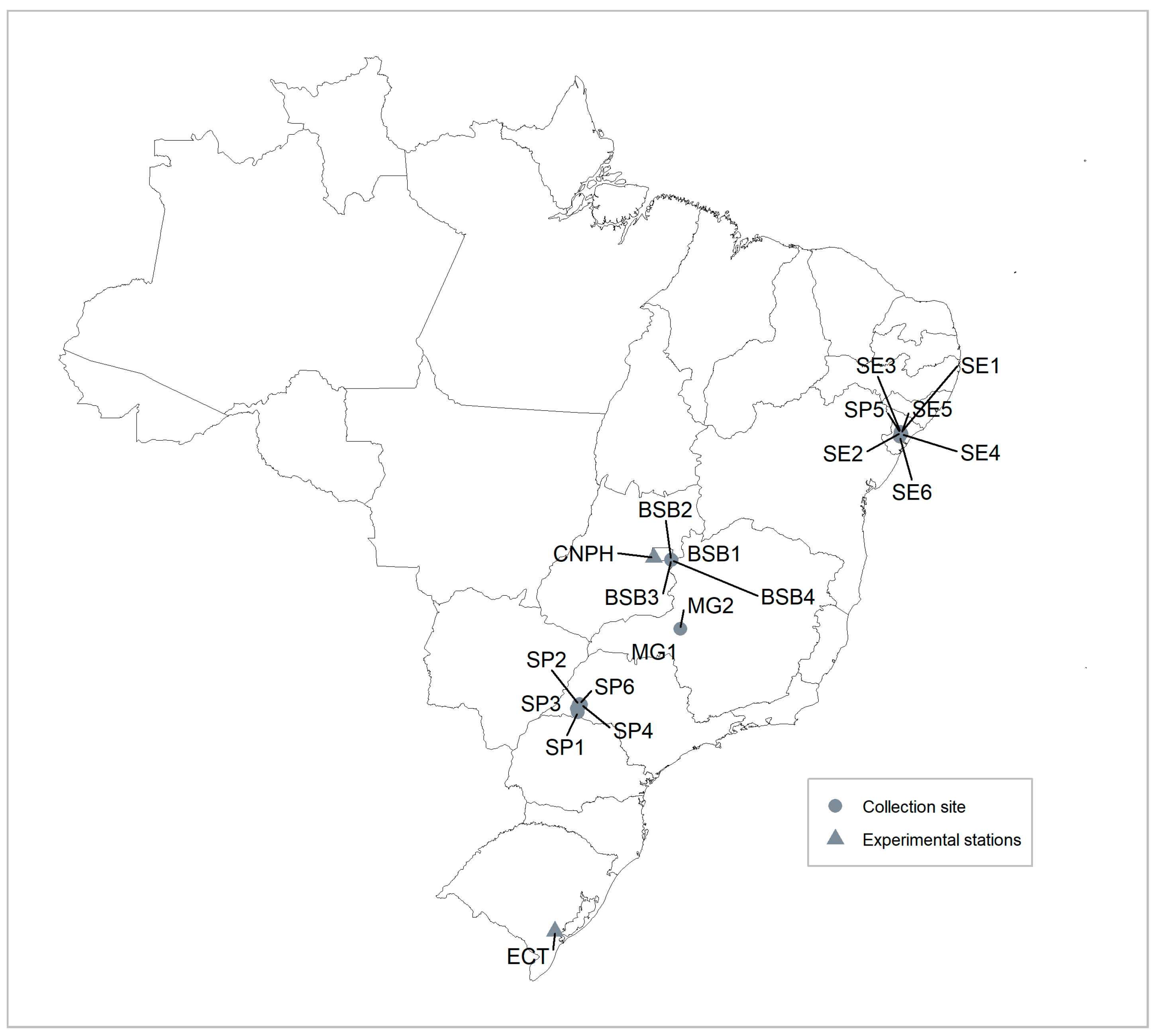

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. DNA Isolation

2.3. SSR Analysis

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. SSR Scoring and Combined Analysis

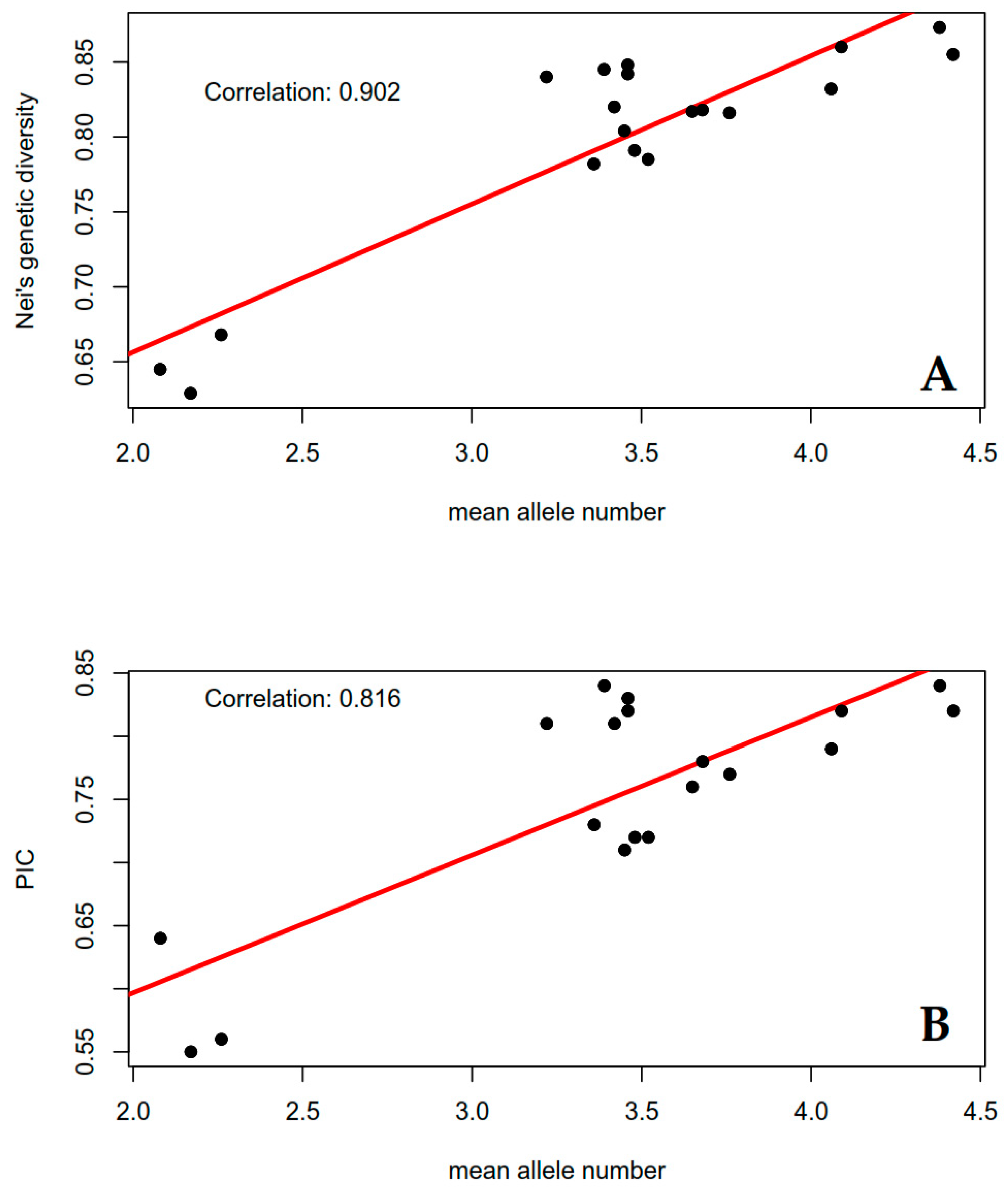

2.4.2. Allelic Frequencies, Polymorphism, and Diversity Estimates

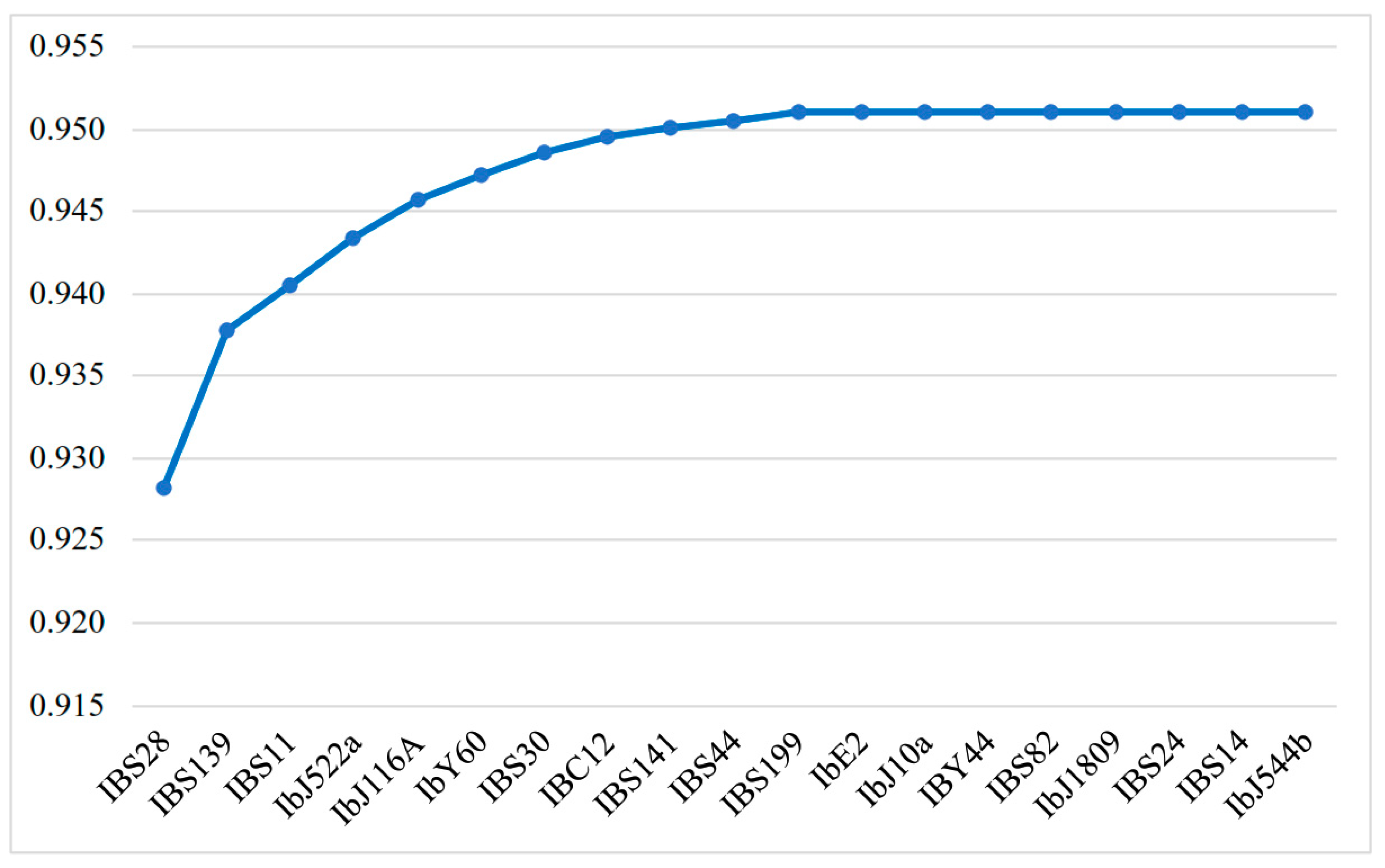

2.4.3. Discriminatory Power Index

2.4.4. Clustering and Identification of Duplicates

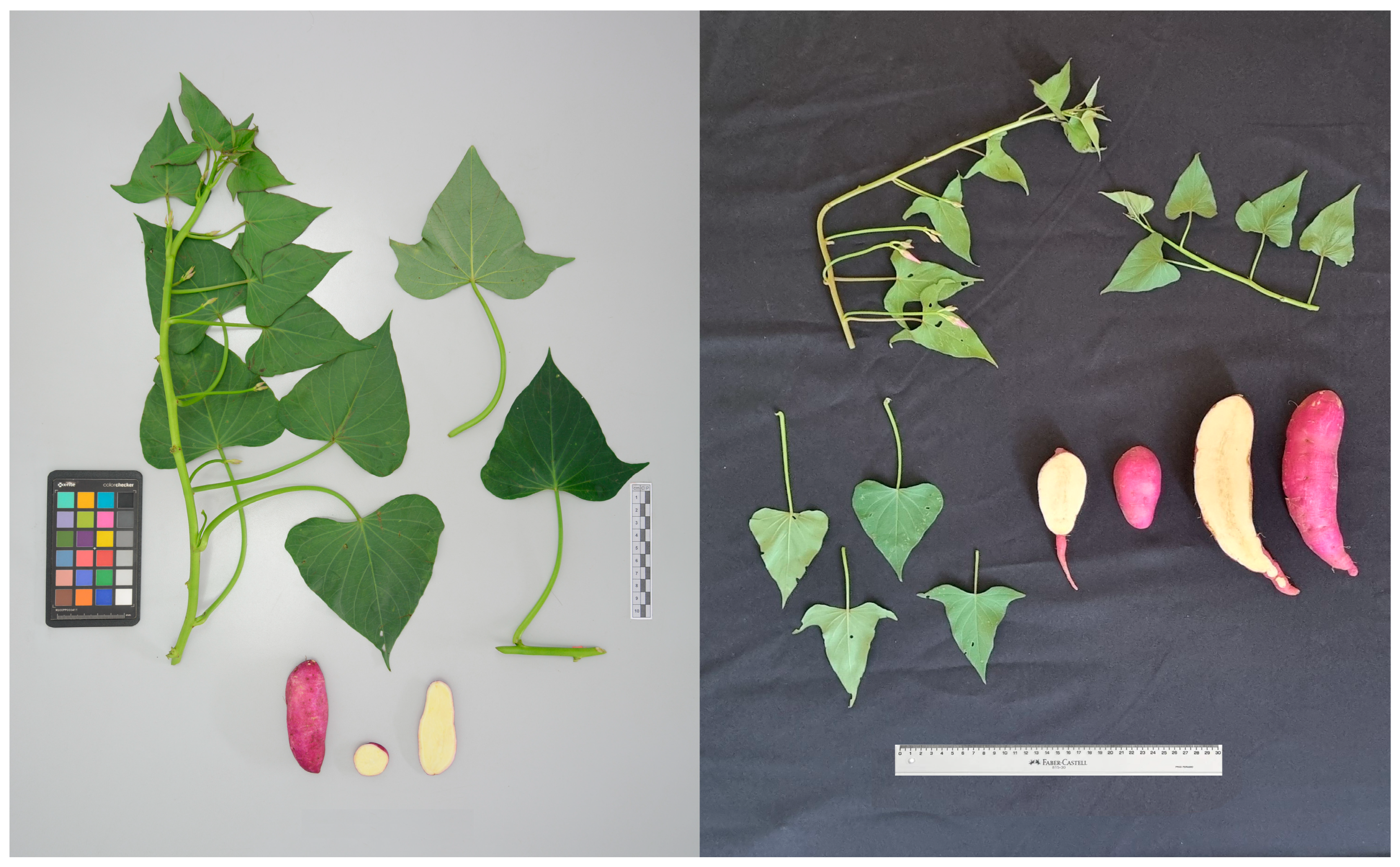

2.5. Morphological Evaluations

3. Results

3.1. Polymorphism and Diversity Estimates

3.2. Discrimination of Samples

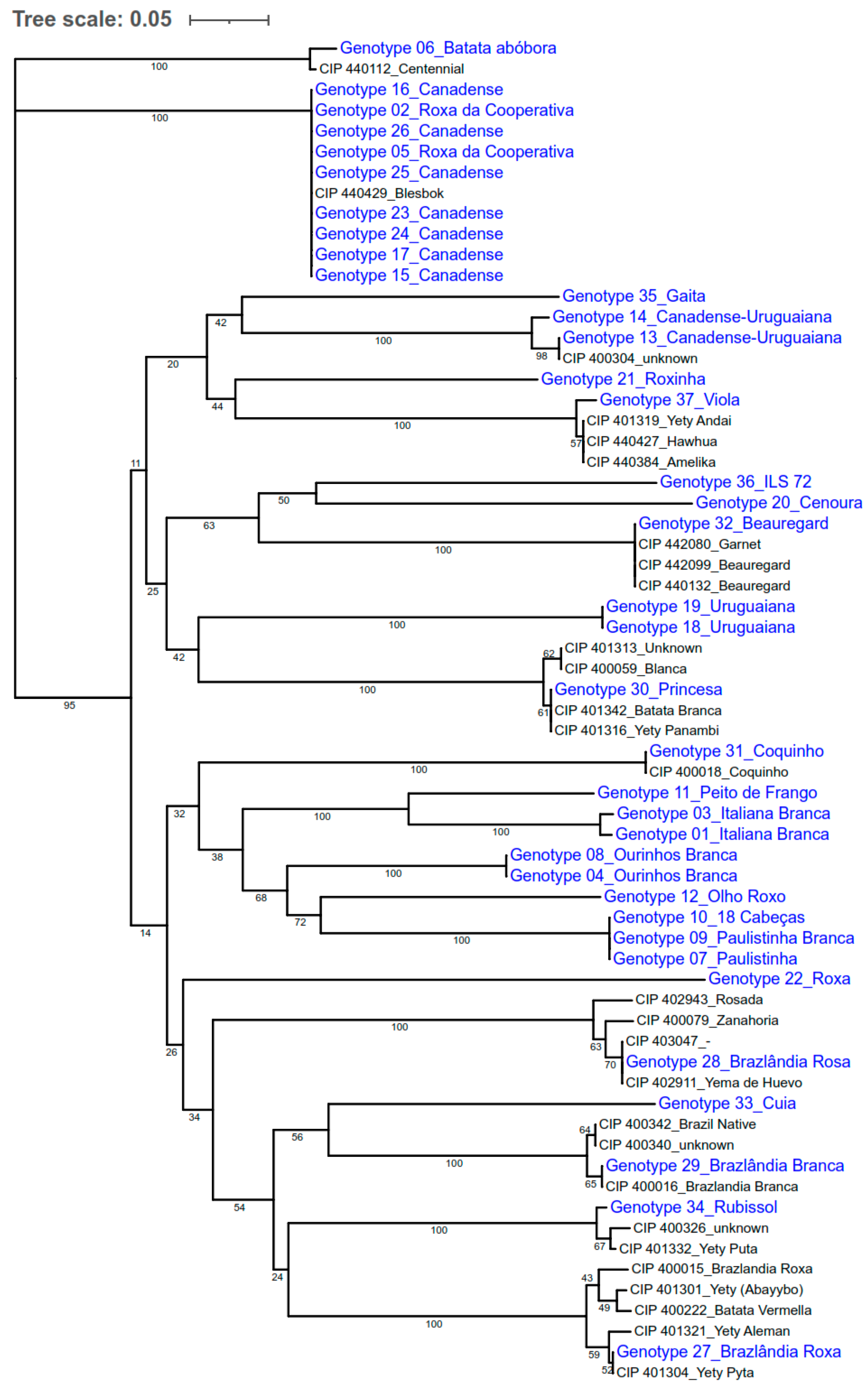

3.3. Comparison of Samples Collected in This Study and the Ones Present at CIP Collection

3.4. Morphological Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roullier, C.; Duputié, A.; Wennekes, P.; Benoit, L.; Fernández Bringas, V.M.; Rossel, G.; Tay, D.; McKey, D.; Lebot, V. Disentangling the origins of cultivated sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.N.; Duarte, L.N.; Samborski, T.; Mello, A.F.S.; Kringel, D.H.; Severo, J. Elaboration of food products with biofortified sweet potatoes: Characterization and sensory acceptability. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2021, 48, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teow, C.; Truong, V.D.; McFeeters, R.; Thompson, R.; Pecota, K.; Yencho, C. Antioxidant activities, phenolic and beta-carotene contents of sweet potato genotypes with varying flesh colours. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, M.; Naziri, D.; San Pedro, J.; Béné, C. Crop resistance and household resilience—The case of cassava and sweetpotato during super-typhoon Ompong in the Philippines. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 62, 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, B.; Githiri, S.; Kariuki, W.; Saha, H. Evaluation of different methods of multiplying sweet potato planting material in coastal lowland Kenya. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 17, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogero, K.; Okuku, H.S.; Wanjala, B.; McEwan, M.; Almekinders, C.; Kreuze, J.; Struik, P.; van der Vlugt, R. Degeneration of cleaned-up, virus-tested sweetpotato seed vines in Tanzania. Crop Prot. 2023, 169, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Produção Agrícola Municipal. Available online: https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/pam/tabelas (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- MAPA. Cultivares de Batata-Doce Registradas. Available online: http://sistemas.agricultura.gov.br/snpc/cultivarweb/cultivares_registradas.php (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- FAO. The Second Report on the State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anglin, N.L.; Robles, R.; Rossel, G.; Alagon, R.; Panta, A.; Jarret, R.L.; Manrique, N.; Ellis, D. Genetic identity, diversity, and population structure of CIP’s weetpotato (I. batatas) germplasm collection. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 660012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hintum, T.; Menting, F.; van Strien, E. Quality indicators for passport data in ex situ genebanks. Plant Genet. Resour. 2011, 9, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibiri, E.B.; Pita, J.S.; Tiendrébéogo, F.; Bangratz, M.; Néya, J.B.; Brugidou, C.; Somé, K.; Barro, N. Characterization of virus species associated with sweetpotato virus diseases in Burkina Faso. Plant Pathol. 2020, 69, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Perrier, X.; Jacquemoud-Collet, J.P. DARwin Dissimilarity Analysis for Windows 2006. Available online: https://darwin.cirad.fr/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- De Silva, H.N.; Hall, A.J.; Rikkerink, E.; McNeilage, M.A.; Fraser, L.G. Estimation of allele frequencies in polyploids under certain patterns of inheritance. Heredity 2005, 95, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, O.J.; Vekemans, X. Spagedi: A versatile computer program to analyse spatial genetic structure at the individual or population levels. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2002, 2, 618–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M. Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics 1978, 89, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.V.; Jasieniuk, M. Polysat: An R package for polyploid microsatellite analysis. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2011, 11, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botstein, D.; White, R.L.; Skolnick, M.; Davis, R.W. Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1980, 32, 314–331. [Google Scholar]

- Tessier, C.; David, J.; This, P.; Boursiquot, J.M.; Charrier, A. Optimization of the choice of molecular markers for varietal identification in Vitis vinifera L. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999, 98, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.A.-O.; Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: An online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W242–W245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIP; AVRDC; IBPGR. Descriptors for Sweet Potato; International Board for Plant Genetic Resources: Rome, Italy, 1991; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- Roullier, C.; Rossel, G.; Tay, D.; McKey, D.; Lebot, V. Combining chloroplast and nuclear microsatellites to investigate origin and dispersal of New World sweet potato landraces. Mol. Ecol. 2011, 20, 3963–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bester, C.; Van den Berg, A.A.; du Plooy, C.P. Blesbok’ Sweetpotato. HortScience 1991, 26, 1229–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francois, G.; Fabrice, V.; Didier, M. Traceability of fruits and vegetables. Phytochemistry 2020, 173, 112291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raphalalani, T.; Maila, Y.; Mphosi, M. Effect of processing methods on the food value of sweet potato variety ‘Blesbok’. Res. Crops 2020, 21, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, S.M.N.M. Cultura da Batata-Doce do Plantio à Comercialização, 1st ed.; Instituto Agronômico de Campinas: Campinas, SP, Brazil, 2013; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, J.G.d.S.; Leonel, M.; Fernandes, A.M.; Nunes, J.G.d.S.; Figueiredo, R.T.d.; Silva, J.A.d.; Menegucci, N.C. Yield and nutritional composition of sweet potatoes storage roots in response to cultivar, growing season and phosphate fertilization. Ciência Rural. 2024, 55, e20240046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, A.F.S.; Silva, G.; de Sousa, R.L.; Barbosa, A.V.S.; Nakasu, E.Y.T.; Silva, G.O.; Biscaia, D.; Pinheiro, J.B. Sweetpotato genotypes ‘CIP BRS Nuti’and ‘Canadense’are resistant to Meloidogyne incognita, M. javanica, and M. enterolobii. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1238–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tairo, F.; Mneney, E.; Kullaya, A. Morphological and agronomical characterization of Sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.] germplasm collection from Tanzania. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2008, 2, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Fongod, A.G.N.; Mih, A.M.; Nkwatoh, T.N. Morphological and agronomical characterization of different accessions of sweet potatoe (Ipomoea batatas) in Cameroon. Int. Res. J. Agric. Sci. Soil Sci. 2012, 2, 234–245. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, F.; Galvao, A.C.; Nicoletto, C.; Sambo, P.; Barcaccia, G. Diversity Analysis of Sweet Potato Genetic Resources Using Morphological and Qualitative Traits and Molecular Markers. Genes 2019, 24, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Identification | Grower Site * | Variety Local Name | Biological Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype 1 | Sergipe, SE | Italiana Branca | Variety |

| Genotype 2 | Sergipe, SE | Roxa da Cooperativa | Variety |

| Genotype 3 | Sergipe, SE | Italiana Branca | Variety |

| Genotype 4 | Sergipe, SE | Ourinhos Branca | Variety |

| Genotype 5 | Sergipe, SE | Roxa da Cooperativa | Variety |

| Genotype 6 | Sergipe, SE | Batata abóbora | Variety |

| Genotype 7 | Sergipe, SE | Paulistinha | Variety |

| Genotype 8 | Sergipe, SE | Ourinhos Branca | Variety |

| Genotype 9 | Sergipe, SE | Paulistinha Branca | Variety |

| Genotype 10 | Sergipe, SE | 18 Cabeças | Variety |

| Genotype 11 | Sergipe, SE | Peito de Frango | Variety |

| Genotype 12 | Sergipe, SE | Olho Roxo | Variety |

| Genotype 13 | Minas Gerais, MG | Canadense-Uruguaiana | Variety |

| Genotype 14 | Minas Gerais, MG | Canadense-Uruguaiana | Variety |

| Genotype 15 | São Paulo, SP | Canadense | Variety |

| Genotype 16 | São Paulo, SP | Canadense | Variety |

| Genotype 17 | São Paulo, SP | Canadense | Variety |

| Genotype 18 | São Paulo, SP | Uruguaiana | Variety |

| Genotype 19 | São Paulo, SP | Uruguaiana | Variety |

| Genotype 20 | São Paulo, SP | Cenoura | Variety |

| Genotype 21 | São Paulo, SP | Roxinha | Variety |

| Genotype 22 | São Paulo, SP | Roxa | Variety |

| Genotype 23 | Brasília, DF | Unknown | Variety |

| Genotype 24 | Brasília, DF | Unknown | Variety |

| Genotype 25 | Brasília, DF | Unknown | Variety |

| Genotype 26 | Brasília, DF | Unknown | Variety |

| Genotype 27 | CNPH, DF | Brazlândia Roxa | Cultivar |

| Genotype 28 | CNPH, DF | Brazlândia Rosada | Cultivar |

| Genotype 29 | CNPH, DF | Brazlândia Branca | Cultivar |

| Genotype 30 | CNPH, DF | Princesa | Cultivar |

| Genotype 31 | CNPH, DF | Coquinho | Cultivar |

| Genotype 32 | CNPH, DF | Beauregard | Cultivar |

| Genotype 33 | ECT, RS | Cuia | Cultivar |

| Genotype 34 | ECT, RS | Rubissol | Cultivar |

| Genotype 35 | ECT, RS | Gaita | Cultivar |

| Genotype 36 | ECT, RS | ILS 72 | Cultivar |

| Genotype 37 | ECT, RS | Viola | Cultivar |

| SSR Marker | Allele Sizes (bp) | Total Number of Alleles | Mean Allele Number | Nei’s Gene Diversity 1 | PIC 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | CIP | Current Study | Without Correction | Corrected by Sample Size | % Change * | Without Correction | Corrected Allele Frequencies | % Change * | |||

| IBS11 | 236–260 | 8 | 3.42 | 3.21 | 3.58 | 0.817 | 0.820 | 0.46 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 2.28 |

| IBS141 | 123–149 | 11 | 4.38 | 4.36 | 4.41 | 0.870 | 0.873 | 0.35 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 1.83 |

| IBS199 | 171–212 | 12 | 4.09 | 4.32 | 3.92 | 0.857 | 0.860 | 0.38 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 2.79 |

| IbJ116A | 205–250 | 10 | 3.45 | 3.21 | 3.62 | 0.801 | 0.804 | 0.44 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 8.18 |

| IbE2 | 109–142 | 11 | 3.22 | 2.89 | 3.46 | 0.836 | 0.840 | 0.43 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 1.22 |

| IBS30 | 189–241 | 9 | 3.48 | 3.39 | 3.54 | 0.787 | 0.791 | 0.46 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 4.96 |

| IBS82 | 141–163 | 8 | 3.68 | 4.09 | 3.43 | 0.814 | 0.818 | 0.45 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 1.13 |

| IBS28 | 187–228 | 11 | 4.42 | 4.21 | 4.58 | 0.852 | 0.855 | 0.36 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 2.19 |

| IBC12 | 111–132 | 8 | 3.65 | 3.68 | 3.62 | 0.813 | 0.817 | 0.42 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 3.71 |

| IBS139 | 304–348 | 12 | 3.46 | 3.29 | 3.59 | 0.838 | 0.842 | 0.44 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.60 |

| IBY44 | 183–216 | 8 | 4.06 | 4.07 | 4.05 | 0.829 | 0.832 | 0.37 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 1.58 |

| IBS44 | 127–151 | 8 | 3.46 | 3.39 | 3.51 | 0.844 | 0.848 | 0.45 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.02 |

| IbJ10a | 191–220 | 7 | 3.41 | 3.30 | 3.50 | 0.841 | 0.845 | 0.46 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 1.74 |

| IbJ522a | 226–265 | 5 | 2.26 | 2.25 | 2.27 | 0.664 | 0.668 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 9.11 |

| IBS14 | 192–200 | 3 | 2.08 | 2.11 | 2.05 | 0.642 | 0.645 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 13.37 |

| IbJ1809 | 143–155 | 5 | 3.36 | 3.57 | 3.19 | 0.778 | 0.782 | 0.47 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 1.42 |

| IBY60 | 188–206 | 8 | 3.76 | 4.15 | 3.47 | 0.812 | 0.816 | 0.43 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 2.04 |

| IBS24 | 149–169 | 6 | 3.53 | 3.56 | 3.51 | 0.781 | 0.785 | 0.44 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 4.25 |

| IbJ544b | 191–211 | 6 | 2.17 | 2.04 | 2.27 | 0.625 | 0.629 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 3.28 |

| SSR Marker | NP | I | C | D | DL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBS11 | 8 | 21 | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| IBS141 | 11 | 21 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.92 |

| IBS199 | 12 | 21 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.92 |

| IbJ116A | 10 | 21 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.91 |

| IbE2 | 11 | 20 | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.92 |

| IBS30 | 9 | 16 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| IBS82 | 8 | 19 | 0.11 | 0.89 | 0.88 |

| IBS28 | 11 | 22 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.93 |

| IBC12 | 8 | 18 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| IBS139 | 13 | 22 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.92 |

| IBY44 | 8 | 16 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| IBS44 | 8 | 21 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.92 |

| IbJ10a | 7 | 19 | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| IbJ522a | 5 | 8 | 0.15 | 0.85 | 0.84 |

| IBS14 | 3 | 6 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.78 |

| IbJ1809 | 5 | 13 | 0.13 | 0.87 | 0.86 |

| IbY60 | 8 | 20 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| IBS24 | 6 | 11 | 0.14 | 0.86 | 0.85 |

| IbJ544b | 6 | 8 | 0.27 | 0.73 | 0.72 |

| Accession Number | Country of Origin | Biological Status | Digital Object Identifier (DOI) | Accession Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP400015 | Brazil | ImpVariety | 10.18730/2C8= | Brazlandia Roxa |

| CIP400016 | Brazil | ImpVariety | 10.18730/2C9U | Brazlandia Branca |

| CIP400018 | Brazil | ImpVariety | 10.18730/2CB1 | Coquinho |

| CIP400059 | Argentina | LandRace | 10.18730/2DC$ | Blanca |

| CIP400079 | Argentina | LandRace | 10.18730/2DWD | Zanahoria |

| CIP400222 | Brazil | LandRace | 10.18730/2J0$ | Batata Vermella |

| CIP400304 | Brazil | Landrace | 10.18730/2MD0 | Unknown |

| CIP400326 | Brazil | Landrace | 10.18730/2N2N | Unknown |

| CIP400340 | Brazil | Landrace | 10.18730/2NF$ | Unknown |

| CIP400342 | Brazil | LandRace | 10.18730/2NG= | Brazil Native |

| CIP401301 | Paraguay | LandRace | 10.18730/3AK7 | Yety (Abayybo) |

| CIP401304 | Paraguay | LandRace | 10.18730/3APA | Yety Pyta |

| CIP401313 | Paraguay | LandRace | 10.18730/3AZK | Unknown |

| CIP401316 | Paraguay | LandRace | 10.18730/3B2P | Yety Panambi |

| CIP401319 | Paraguay | LandRace | 10.18730/3B5S | Yety Andai |

| CIP401321 | Paraguay | LandRace | 10.18730/3B7V | Yety Aleman |

| CIP401332 | Paraguay | LandRace | 10.18730/3BJ1 | Yety Puta |

| CIP401342 | Paraguay | LandRace | 10.18730/3BWB | Batata Branca |

| CIP402911 | Argentina | LandRace | 10.18730/3KEZ | Yema de Huevo |

| CIP402943 | Argentina | LandRace | 10.18730/3KR4 | Rosada |

| CIP403047 | Argentina | LandRace | 10.18730/P64NW | Unknown |

| CIP440112 | United States | ImpVariety | 10.18730/654J | Centennial |

| CIP440132 | United States | ImpVariety | 10.18730/65R1 | Beauregard |

| CIP440384 | Tonga | LandRace | 10.18730/6D8K | Amelika |

| CIP440427 | Philippines | LandRace | 10.18730/6EGP | Hawhua |

| CIP440429 | South Africa | ImpVariety | 10.18730/P79T~ | Blesbok |

| CIP442080 | United States | ImpVariety | 10.18730/7FC1 | Garnet |

| CIP442099 | United States | ImpVariety | 10.18730/19JEJ9 | Beauregard |

| Genotypes | Plant Type | Vine Length | Vine 1º Pigmentation | Vine Pubescens | General Outline | Foliage Color-Immature Leaf Color |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype 11 | Erect | Very short | Green | Sparse | Lobed | Green |

| Genotype 01 | Erect | Very short | Green | Absent | Triangular | Green |

| Genotype 03 | ||||||

| Genotype 04 | Semi-erect | Short | Mostly dark purple | Moderate | Lobed | Green |

| Genotype 08 | ||||||

| Genotype 12 | Semi-erect | Short | Green | Moderate | Hastate | Green with purple edge |

| Genotype 07 | Erect | Short | Green | Absent | Lobed | Green with purple edge |

| Genotype 09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mello, A.F.S.; Robles, R.; de Simon, G.R.M.; da Silva, G.O.; Montes, S.M.N.M.; Nunes, M.U.C.; Pereira, J.L.; Nakasu, E.Y.T.; Vollmer, R.; Ellis, D.; et al. Deciphering the Origins of Commercial Sweetpotato Genotypes Using International Genebank Data. Biology 2026, 15, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010091

Mello AFS, Robles R, de Simon GRM, da Silva GO, Montes SMNM, Nunes MUC, Pereira JL, Nakasu EYT, Vollmer R, Ellis D, et al. Deciphering the Origins of Commercial Sweetpotato Genotypes Using International Genebank Data. Biology. 2026; 15(1):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010091

Chicago/Turabian StyleMello, Alexandre F. S., Ronald Robles, Genoveva R. M. de Simon, Giovani O. da Silva, Sonia M. N. M. Montes, Maria U. C. Nunes, Jose L. Pereira, Erich Y. T. Nakasu, Rainer Vollmer, David Ellis, and et al. 2026. "Deciphering the Origins of Commercial Sweetpotato Genotypes Using International Genebank Data" Biology 15, no. 1: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010091

APA StyleMello, A. F. S., Robles, R., de Simon, G. R. M., da Silva, G. O., Montes, S. M. N. M., Nunes, M. U. C., Pereira, J. L., Nakasu, E. Y. T., Vollmer, R., Ellis, D., Valencia-Límaco, V., & Azevedo, V. C. R. (2026). Deciphering the Origins of Commercial Sweetpotato Genotypes Using International Genebank Data. Biology, 15(1), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010091