Nonlinear Responses of Phytoplankton Communities to Environmental Drivers in a Tourist-Impacted Coastal Zone: A GAMs-Based Study of Beihai Silver Beach

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

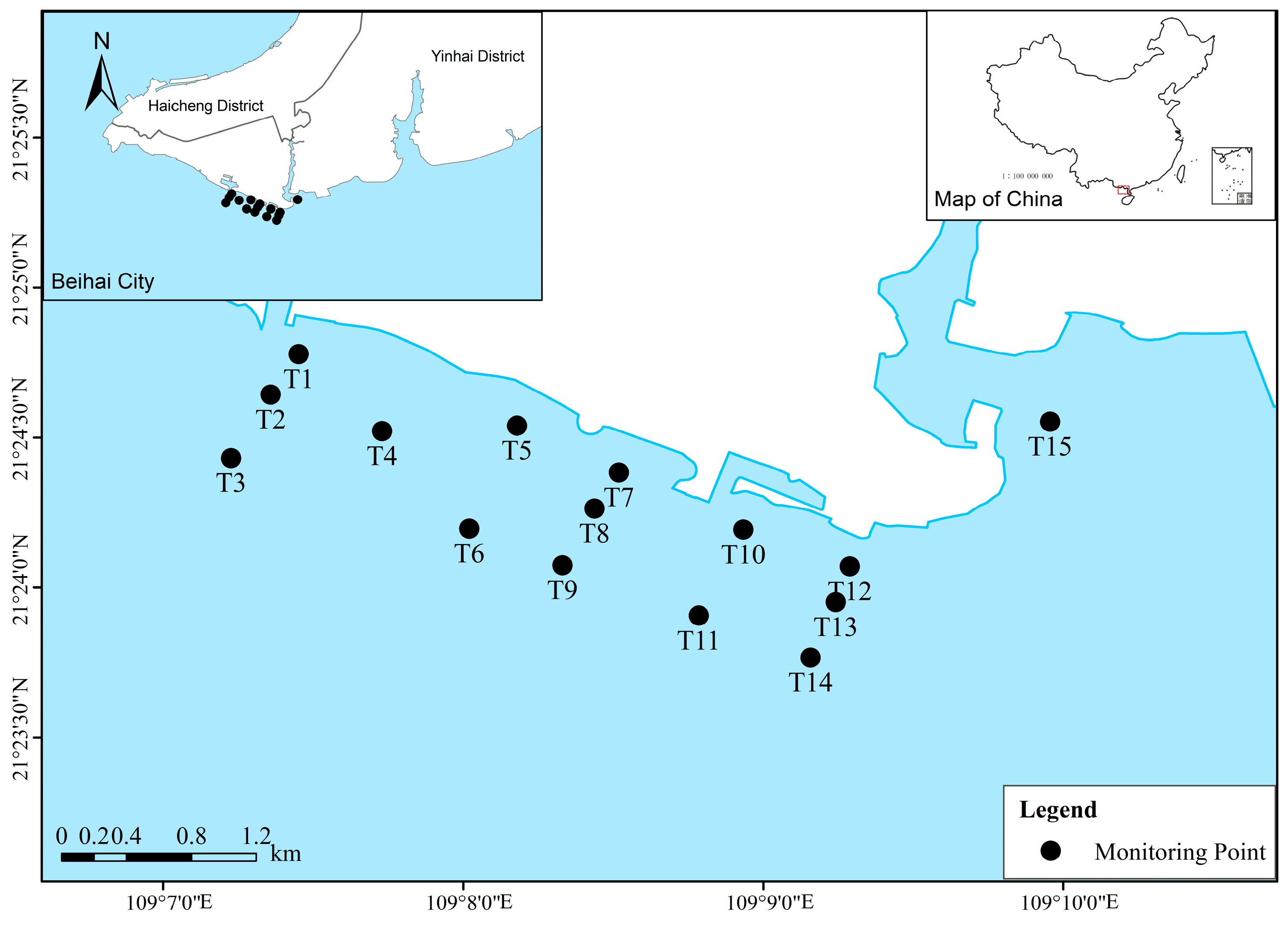

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling and Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Communities Diversity and Dominance

2.3.2. GAMs Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Water Quality Indicators

3.2. Variation Characteristics of Phytoplankton Community Structure

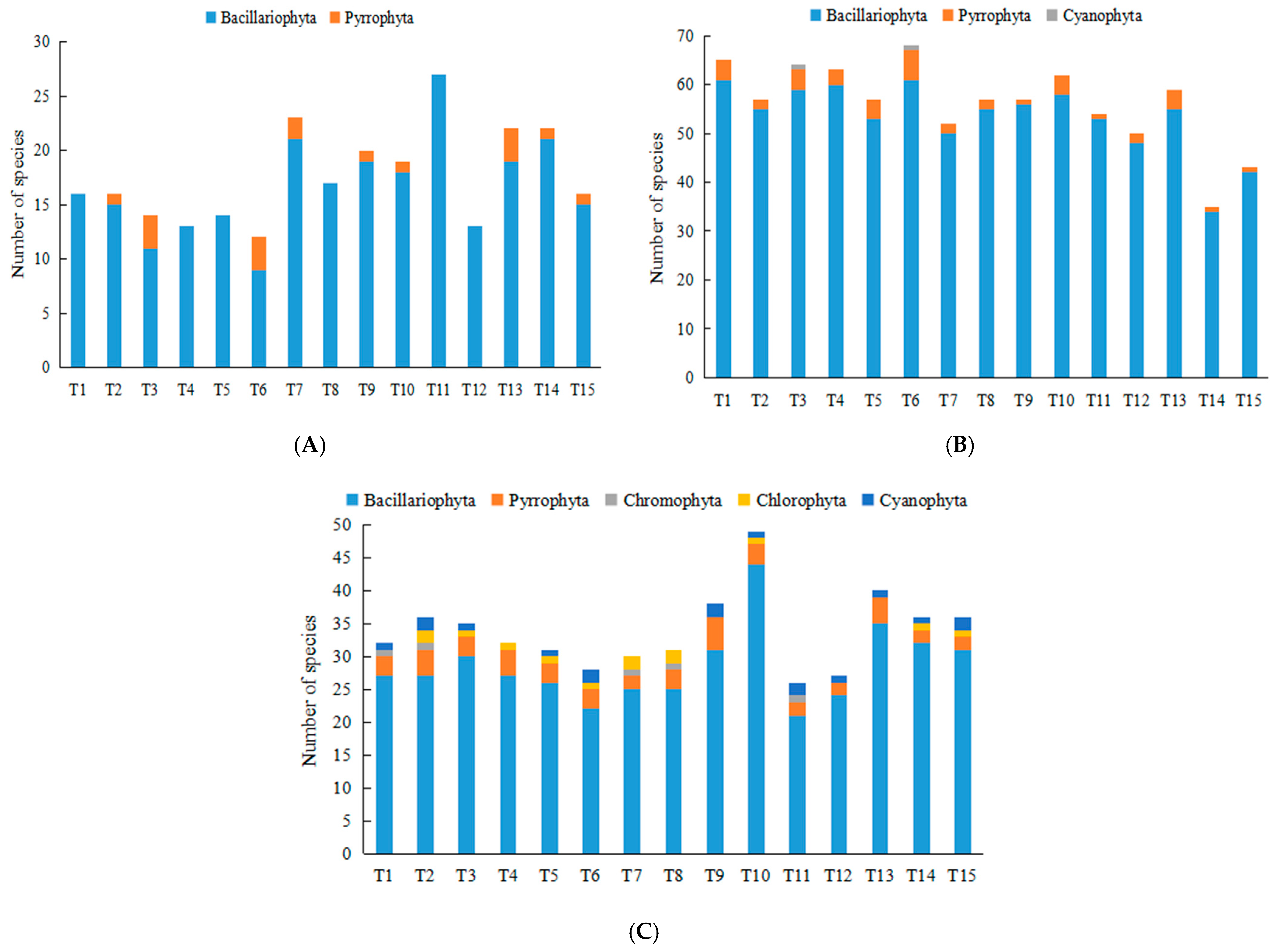

3.2.1. Species Composition of Phytoplankton

3.2.2. Dominant Species

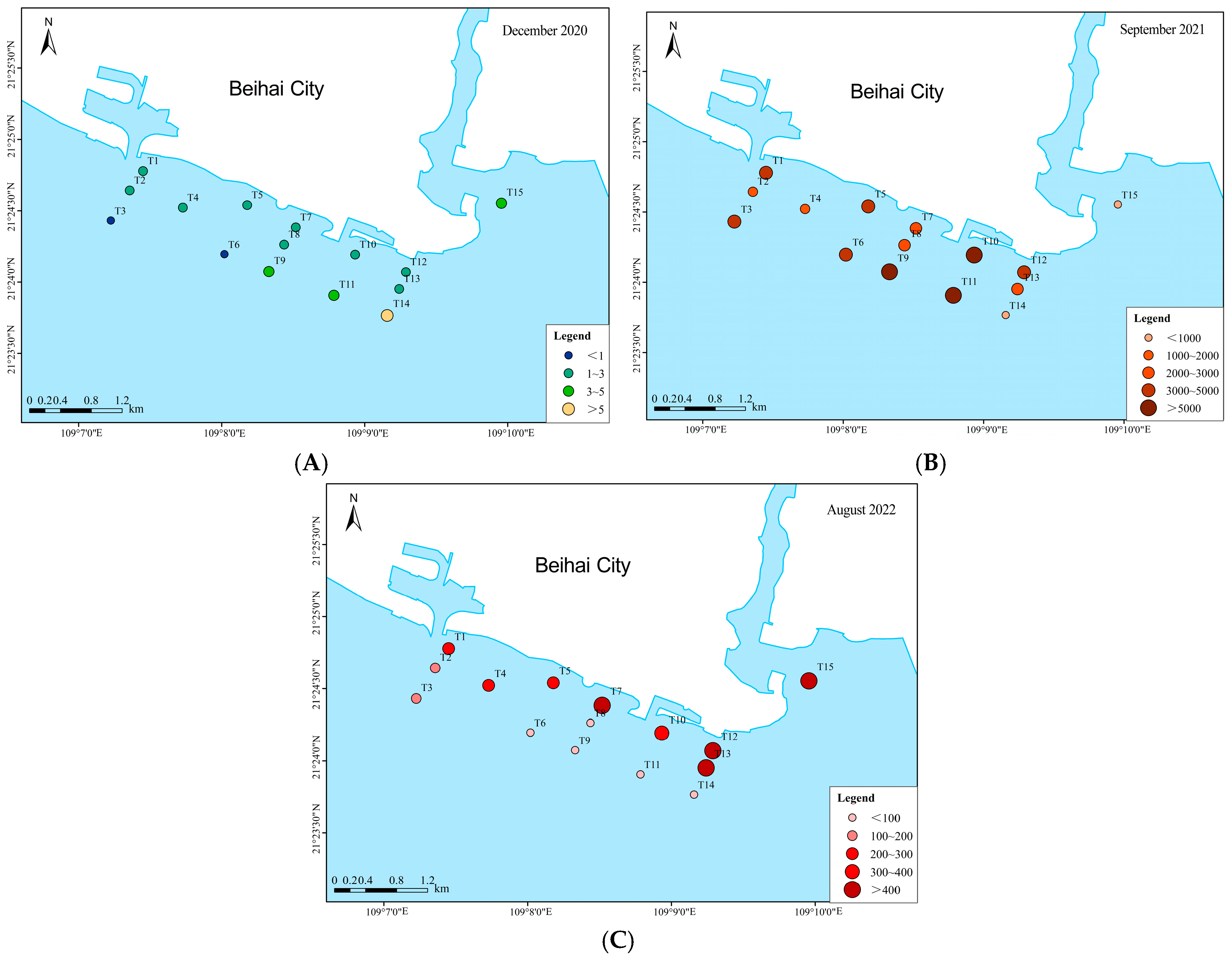

3.2.3. Community Composition Characteristics

3.2.4. Diversity Index

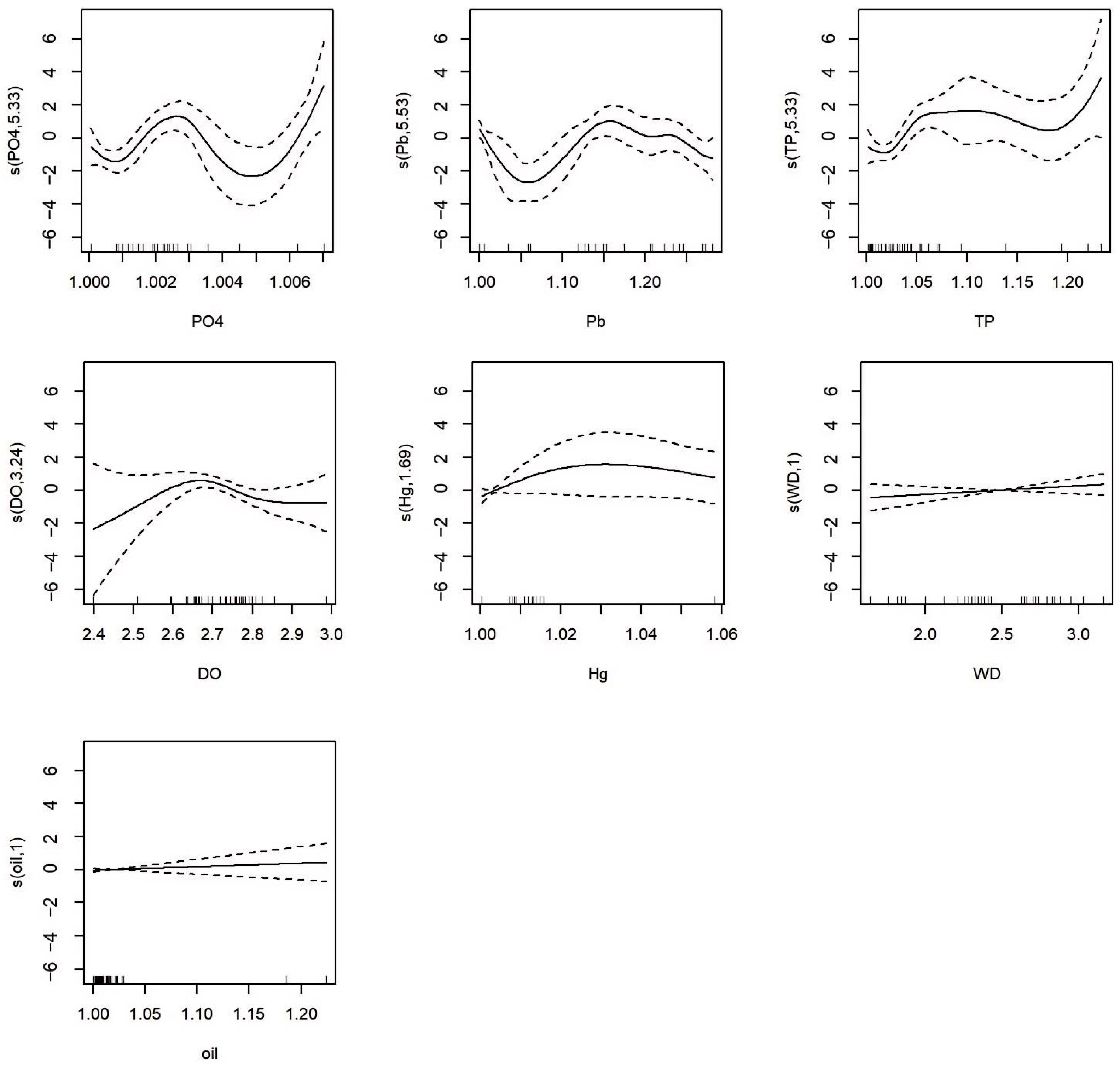

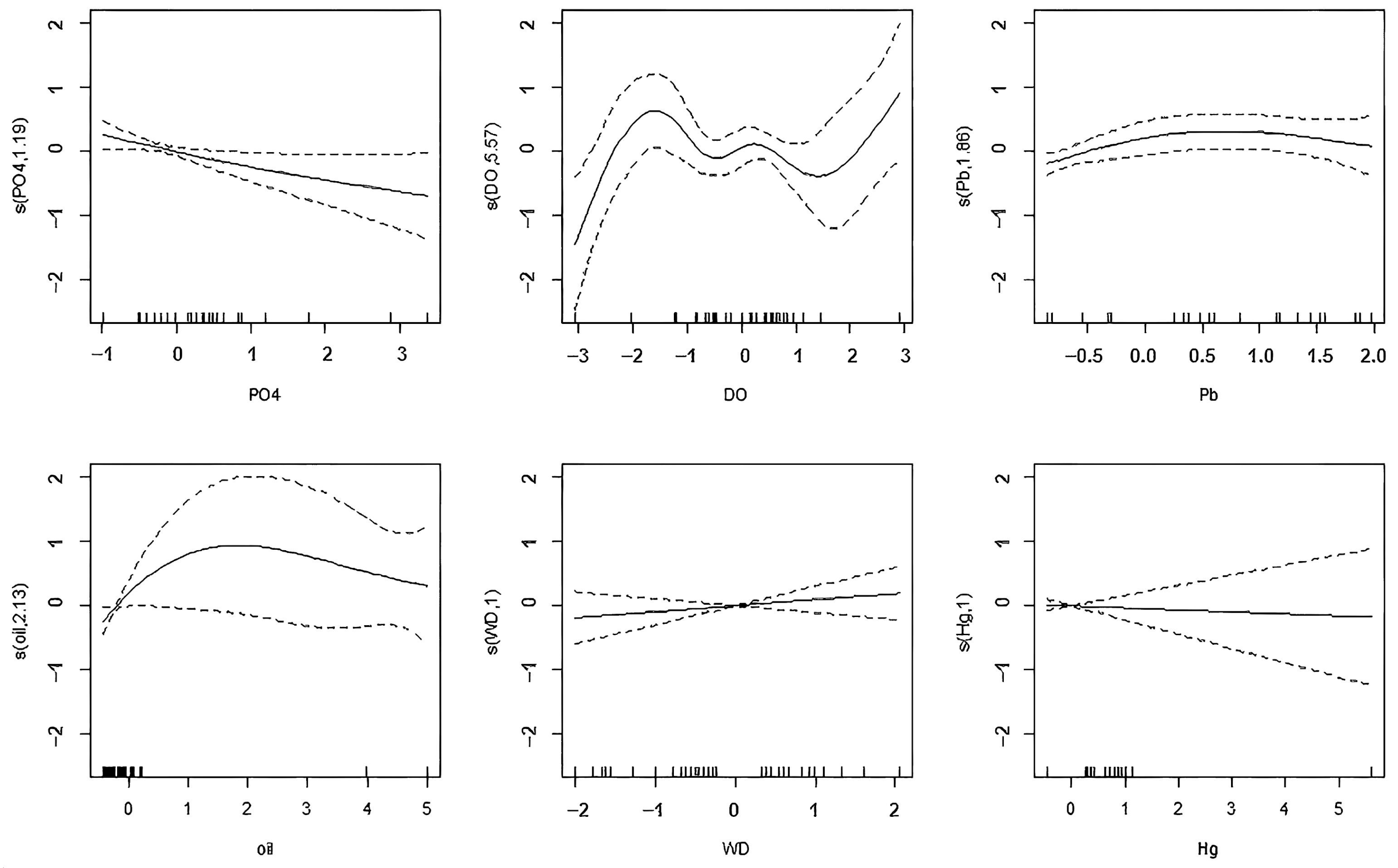

3.3. GAMs-Based Analysis of Phytoplankton Community Characteristic Indices and Environmental Drivers

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Phytoplankton Community

4.2. Key Environmental Drivers Identified by GAMs

4.3. Implications for Coastal Management

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cloern, J.; Foster, S.; Kleckner, A. Phytoplankton primary production in the world’s estuarine-coastal ecosystems. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 2477–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, W.; Sun, X.; Hou, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; et al. Seasonal and spatial variations in nutrients under the influence of natural and anthropogenic factors in coastal waters of the northern Yellow Sea, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 175, 113171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuatters-Gollop, A.; Gilbert, A.J.; Mee, L.D.; Vermaat, J.E.; Artioli, Y.; Humborg, C.; Wulff, F. How well do ecosystem indicators communicate the effects of anthropogenic eutrophication? Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2009, 82, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, D.; Rastelli, E.; Casotti, R.; Manna, V.; Trano, A.C.; Balestra, C.; Santinelli, C.; Saggiomo, M.; Sansone, C.; Corinaldesi, C.; et al. Microplastics alter the functioning of marine microbial ecosystems. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beardall, J.; Stojkovic, S.; Larsen, S. Living in a high CO2 world: Impacts of global climate change on marine phytoplankton. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2009, 2, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Silliman, B. Climate Change, Human Impacts, and Coastal Ecosystems in the Anthropocene. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R1021–R1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Lu, X.; Su, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Cao, X.; Li, Q.; Su, J.; Ittekkot, V.; et al. Major threats of pollution and climate change to global coastal ecosystems and enhanced management for sustainability. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 239, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, P.; Tian, C.; Zhang, C.; Du, J.; Guo, H.; Wang, B. Coastal eutrophication in China: Trend, sources, and ecological effects. Harmful Algae 2021, 107, 102058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tao, X.; Liu, C.; Wei, G.; He, X.; Yao, Q.; Chen, W.; Li, B. Nutrients and Water Quality in the Beihai Peninsula of Guangxi During Summers; Marine Sciences; China Science Publishing & Media Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2021; Volume 45, pp. 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Wei, C.; Gao, J.; Ji, C. Distribution, sources and ecological risk analysis of DDTs and PCBs in surface sediments of Beihai sea coast. Mar. Sci. 2021, 28, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zuur, A.; Ieno, E.; Elphick, C. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.J.; Miller, D.L.; Simpson, G.L.; Ross, N. Hierarchical generalized additive models in ecology: An introduction with mgcv. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Lin, M. Atlas of Marine Biota of China; China Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 1–283. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Dong, S. Atlas of Common Marine Planktonic Diatoms in Chinese Waters; China Ocean University Press: Qingdao, China, 2006; pp. 1–267. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, D.; Chen, J.; Huang, K. The Marine Planktonic Diatoms of China; Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers: Shanghai, China, 1965; pp. 1–230. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Wei, Y. The Freshwater Algae of China: Systematics, Taxonomy and Ecology; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 1–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, D.; Cheng, Z. The Marine Benthic Diatoms of China; China Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 1982; Volume 1, pp. 1–323. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, D.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, S.; Ma, J. The Marine Benthic Diatoms of China; China Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 1992; Volume 2, pp. 1–437. [Google Scholar]

- Dufrene, M.; Legendre, P. Species assemblages and indicator species: The need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol. Monogr. 1997, 67, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C. A mathematical theory of communication. ACM SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 2001, 5, 3–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielou, E. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. J. Theor. Biol. 1966, 13, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Niu, Y.; Yu, H.; Niu, Y. Relationship of chlorophyll-a content and environmental factors in Lake Taihu based on GAM model. Res. Environ. Sci. 2018, 31, 886–892. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, S.; Bai, Y.; Ali, S.; Zhang, J. Temporal-spatial distribution of chlorophyll-a and impacts of environmental factors in the Bohai sea and yellow sea. IEEE. Access. 2019, 7, 160947–160960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovers, E.; Stoklosa, J.; Warton, D. Fitting log-Gaussian Cox processes using generalized additive model software. Am. Stat. 2024, 78, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Faraway, J. Generalized linear models. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd ed.; Peterson, P., Baker, E., McGaw, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Vittinghoff, E.; McCulloch, C.; Glidden, D.; Shiboski, S.C. Linear and non-linear regression methods in epidemiology and biostatistics. In Handbook of Statistics; Rao, C., Miller, J., Rao, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 27, pp. 148–186. [Google Scholar]

- Winder, M.; Cloern, J. The annual cycles of phytoplankton biomass. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010, 365, 3215–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloern, J. Our evolving conceptual model of the coastal eutrophication problem. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001, 210, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuatters-Gollop, A.; Raitsos, D.; Edwards, M.; Pradhan, Y.; Mee, L.D.; Lavender, S.J.; Attrill, M.J. A long-term chlorophyll dataset reveals regime shift in North Sea phytoplankton biomass unconnected to nutrient levels. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2007, 52, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, M. Paradox of Enrichment: Destabilization of Exploitation Ecosystems in Ecological Time. Science 1971, 171, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, R.; Marino, R. Nitrogen as the limiting nutrient for eutrophication in coastal marine ecosystems: Evolving views over three decades. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2006, 51, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, A.; Wang, W. Cadmium and zinc toxicity to a marine diatom: Evidence for an intracellular gradient of toxicity. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006, 25, 2941–2946. [Google Scholar]

- Fleeger, J.; Carman, K.; Nisbet, R. Indirect effects of contaminants in aquatic ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2003, 317, 207–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté, I.; Darling, E.; Brown, C. Interactions among ecosystem stressors and their importance in conservation. Proc. R. Soc. B 2016, 283, 20152592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelbach, G.G.; Steiner, C.F.; Scheiner, S.M.; Gross, K.L.; Reynolds, H.L.; Waide, R.B.; Willig, M.R.; Dodson, S.I.; Gough, L. What is the observed relationship between species richness and productivity? Ecology 2001, 82, 2381–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B. Biodiversity improves water quality through niche partitioning. Nature 2011, 472, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C. The Ecology of Phytoplankton; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cloern, J.; Jassby, A. Patterns and Scales of Phytoplankton Variability in Estuarine–Coastal Ecosystems. Estuaries Coasts 2010, 33, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, R. Limnology: Lake and River Ecosystems; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, R.; Rosenberg, R. Spreading dead zones and consequences for marine ecosystems. Science 2008, 321, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.; Schindler, D. Eutrophication science: Where do we go from here? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuur, A.; Ieno, E. A protocol for conducting and presenting results of regression-type analyses. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloern, J.; Jassby, A. Drivers of change in estuarine-coastal ecosystems: Discoveries from four decades of study in San Francisco Bay. Rev. Geophys. 2012, 50, RG4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environmental Factors | December 2020 | September 2021 | August 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT (°C) | 19.31 ± 0.09 | 30.4 ± 0.09 | 30.7 ± 0.13 |

| WD (m) | 4.38 ± 0.21 | 6.07 ± 0.45 | 5.49 ± 0.57 |

| Sal | 31.39 ± 0.03 | 26.06 ± 0.17 | 21.18 ± 1.40 |

| DO (mg/L) | 6.67 ± 0.03 | 6.02 ± 0.13 | 6.45 ± 0.16 |

| pH | 8.07 ± 0.01 | 8.27 ± 0.01 | 8.19 ± 0.02 |

| SS (mg/L) | 5.82 ± 0.34 | 5.82 ± 0.33 | 9.93 ± 0.45 |

| Oil (mg/L) | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.01 ± 0.002 | 0.02 ± 0.004 |

| PO43− (mg/L) | 0.001 ± 0.0008 | 0.006 ± 0.0006 | 0.003 ± 0.0006 |

| SiO32− (mg/L) | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 |

| NO2−-N (mg/L) | 0.0003 ± 0.0001 | 0.001 ± 0.0004 | 0.029 ± 0.005 |

| NO3−-N (mg/L) | 0.015 ± 0.003 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.11 ± 0.02 |

| NH4+-N (mg/L) | 0.029 ± 0.01 | 0.008 ± 0.005 | 0.003 ± 0.001 |

| COD (mg/L) | 0.31 ± 0.09 | 1.92 ± 0.07 | 1.68 ± 0.11 |

| TP (mg/L) | 0.01 ± 0.001 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.05 ± 0.007 |

| TN (mg/L) | 3.17 ± 0.34 | 0.03 ± 0.005 | 0.22 ± 0.02 |

| Chl-a (mg/L) | 1.87 ± 0.27 | 0.01 ± 0.001 | 3.06 ± 0.32 |

| Cu (μg/L) | 1.1 ± 0.00 | 1.39 ± 0.72 | 10.22 ± 7.20 |

| Pb (μg/L) | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.16 ± 0.17 | 0.42 ± 0.18 |

| Zn (μg/L) | 3.1 ± 0.00 | 3.83 ± 2.21 | 48.23 ± 15.10 |

| Cd (μg/L) | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| Hg (μg/L) | 0.028 ± 0.03 | 0.007 ± 0.00 | 0.007 ± 0.00 |

| As (μg/L) | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.11 | 0.53 ± 0.09 |

| Cr (μg/L) | 0.4 ± 0.00 | 0.45 ± 0.11 | 0.04 ± 0.00 |

| Dominant Species | December 2020 | September 2021 | August 2022 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occurrence Frequency/% | Y | Occurrence Frequency/% | Y | Occurrence Frequency/% | Y | |

| Skeletonema costatum | 100.00 | 0.380 | 100.00 | 0.395 | 100.00 | 0.023 |

| Melosira sulcata | 60.00 | 0.067 | 100.00 | 0.028 | ||

| Thalassionema nitzschioides | 93.33 | 0.056 | ||||

| Chaetoceros lorenzianus | 93.33 | 0.055 | 100.00 | 0.174 | ||

| Rhizosolenia imbricata | 93.33 | 0.050 | ||||

| Chaetoceros affinis | 86.67 | 0.041 | 100.00 | 0.181 | ||

| Pseudo-nitzschia pungens | 73.33 | 0.025 | ||||

| Bacteriastrum hyalinum | 100.00 | 0.120 | 100.00 | 0.133 | ||

| Thalassiothrix frauenfeldii | 100.00 | 0.023 | ||||

| Hemidiscus cuneiformis | 100.00 | 0.270 | ||||

| Bacteriastrum varians | 100.00 | 0.112 | ||||

| Nitzschia longissima | 100.00 | 0.042 | ||||

| Chaetoceros pelagicus | 100.00 | 0.035 | ||||

| Nitzschia sublanceolata | 100.00 | 0.029 | ||||

| Peridinium pentagonum | 100.00 | 0.023 | ||||

| Model Fitness | S | H′ |

|---|---|---|

| Values | Values | |

| R2 | 0.91 | 0.436 |

| Generalized Cross-Validation (GCV) | 0.90 | 0.354 |

| Variables | Effective Degrees of Freedom (edf) | Reference Degree of Freedom (Ref.df) | F Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s (PO43−) | 5.333 | 6.077 | 5.878 | 9.080 × 10−4 *** |

| s (Pb) | 5.534 | 6.198 | 4.782 | 3.553 × 10−3 ** |

| s (TP) | 5.326 | 6.086 | 4.193 | 5.939 × 10−3 ** |

| s (DO) | 3.243 | 3.947 | 2.767 | 0.062 |

| s (Hg) | 1.690 | 1.932 | 1.344 | 0.276 |

| s (WD) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.171 | 0.291 |

| s (oil) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.567 | 0.459 |

| Variables | Effective Degrees of Freedom (edf) | Reference Degree of Freedom (Ref.df) | F Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s (PO43−) | 1.195 | 1.350 | 4.445 | 0.036 * |

| s (DO) | 5.574 | 6.567 | 2.732 | 0.027 * |

| s (Pb) | 1.862 | 2.246 | 2.742 | 0.077 |

| s (oil) | 2.133 | 2.586 | 2.149 | 0.132 |

| s (WD) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.867 | 0.359 |

| s (Hg) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.112 | 0.740 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cheng, D.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, F.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Dang, E. Nonlinear Responses of Phytoplankton Communities to Environmental Drivers in a Tourist-Impacted Coastal Zone: A GAMs-Based Study of Beihai Silver Beach. Biology 2026, 15, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010034

Cheng D, Chen X, Chen Y, Zhu F, Qiao Y, Zhang L, Dang E. Nonlinear Responses of Phytoplankton Communities to Environmental Drivers in a Tourist-Impacted Coastal Zone: A GAMs-Based Study of Beihai Silver Beach. Biology. 2026; 15(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Dewei, Xuyang Chen, Yun Chen, Fangchao Zhu, Ying Qiao, Li Zhang, and Ersha Dang. 2026. "Nonlinear Responses of Phytoplankton Communities to Environmental Drivers in a Tourist-Impacted Coastal Zone: A GAMs-Based Study of Beihai Silver Beach" Biology 15, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010034

APA StyleCheng, D., Chen, X., Chen, Y., Zhu, F., Qiao, Y., Zhang, L., & Dang, E. (2026). Nonlinear Responses of Phytoplankton Communities to Environmental Drivers in a Tourist-Impacted Coastal Zone: A GAMs-Based Study of Beihai Silver Beach. Biology, 15(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010034