Genome-Wide Identification of the OPR Gene Family in Soybean and Its Expression Pattern Under Salt Stress

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of OPR Genes in the 28 Soybean Accessions

2.2. Synteny Relationship and Gene Duplication Analysis

2.3. Gene Structures and Motif Patterns

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.5. Ka/Ks Calculation

2.6. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements

2.7. Protein Interaction Network Analysis

2.8. Analysis of Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns

2.9. Expression Patterns of GmOPRs Under Salt Stress

3. Results

3.1. Distribution, Synteny, and Duplication Events of GmOPRs in the 28 Soybean Accessions

3.2. Gene Structure, Conserved Motifs, and Phylogenetic Analysis

3.3. Selective Pressure Analysis of GmOPRs in the 28 Soybean Accessions

3.4. Cis-Acting Elements Analysis of GmOPRs in the 28 Soybean Accessions

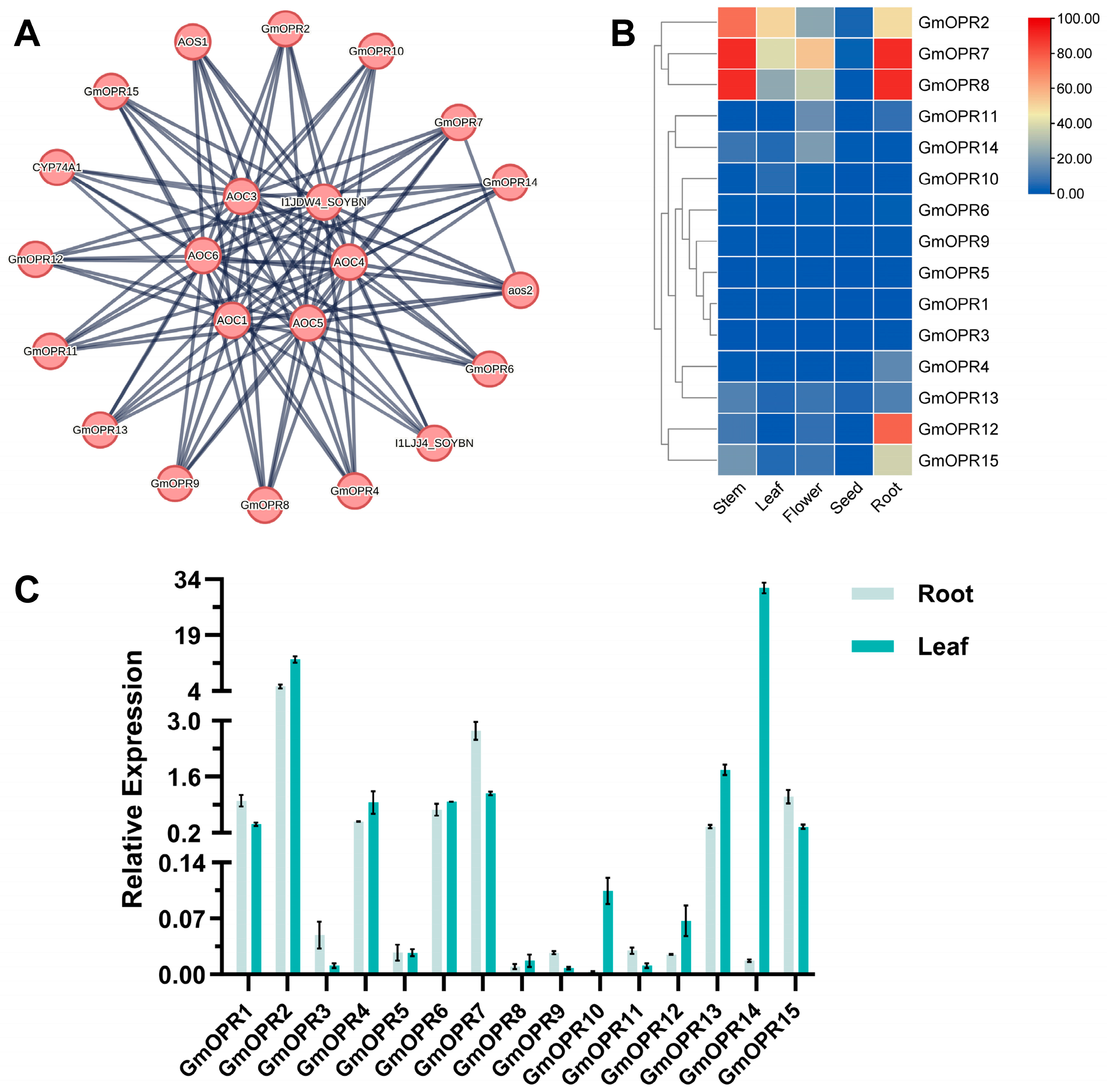

3.5. Protein Interaction Network Prediction and Tissue Expression Pattern Analysis

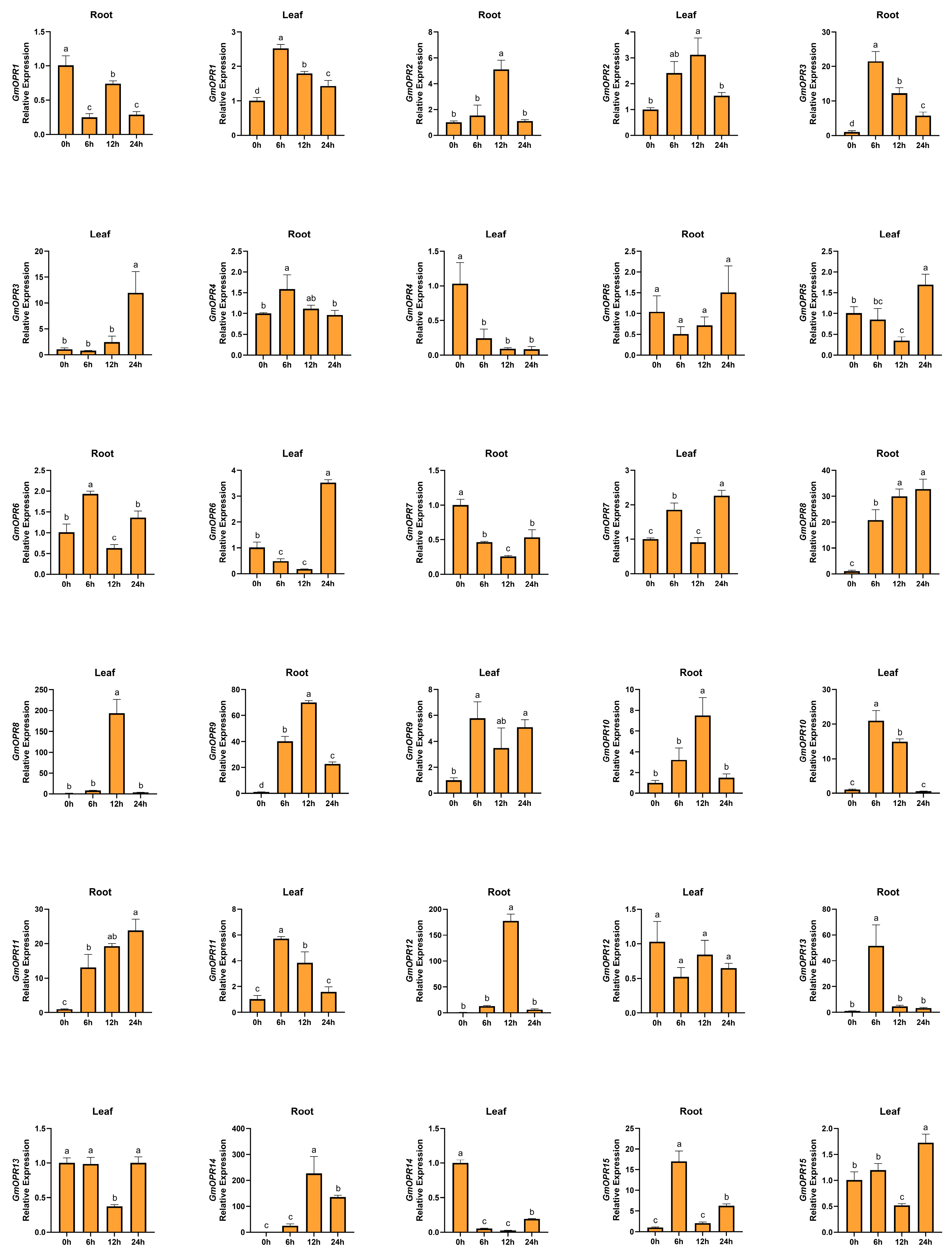

3.6. Analysis of GmOPRs Expression Patterns Under Salt Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, X.; Kui, M.; He, K.; Yang, M.; Du, J.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Y. Jasmonate-regulated root growth inhibition and root hair elongation. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 74, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Shi, L.; Xu, F. JASMONATE RESISTANT 1 negatively regulates root growth under boron deficiency in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 3108–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Su, H.; Guo, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Y.D.; Zhang, N. Jasmonate and aluminum crosstalk in tomato: Identification and expression analysis of WRKYs and ALMTs during JA/Al-regulated root growth. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 154, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H.; Ma, Y.; Wu, Y.; Akbar, A.; Shaban, M.; Ullah, A.; Deng, J.; Khan, A.S.; Chi, H.; Zhu, L.; et al. High-temperature stress suppresses allene oxide cyclase 2 and causes male sterility in cotton by disrupting jasmonic acid signaling. Crop J. 2023, 11, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Hao, M.; Sang, S.; Wen, Y.; Cai, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Mei, D.; Hu, Q. Establishment of new convenient two-line system for hybrid production by targeting mutation of OPR3 in allopolyploid Brassica napus. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Bigotes, A.; Figueroa, P.M.; Figueroa, C.R. Jasmonate metabolism and its relationship with abscisic acid during strawberry fruit development and ripening. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 37, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Feng, Y.; Yuan, S.; Zhao, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, C.; Xue, Z. Different regulatory mechanisms of plant hormones in the ripening of climacteric and non-climacteric fruits: A review. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 107, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.L.; Fan, Z.Q.; Shan, W.; Yin, X.R.; Kuang, J.F.; Lu, W.J.; Chen, J.Y. Association of BrERF72 with methyl jasmonate-induced leaf senescence of Chinese flowering cabbage through activating JA biosynthesis-related genes. Hortic. Res. 2018, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, M.; Guo, Y. Ring/U-Box protein AtUSR1 functions in promoting leaf senescence through JA signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 608589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.M.; Liu, W.C.; Lu, Y.T. CATALASE2 coordinates SA-mediated repression of both auxin accumulation and JA biosynthesis in plant defenses. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.C.; Grunseich, J.M.; Berg-Falloure, K.M.; Tolley, J.P.; Koiwa, H.; Bernal, J.S.; Kolomiets, M.V. Maize OPR2 and LOX10 mediate defense against fall armyworm and western corn rootworm by tissue-specific regulation of jasmonic acid and ketol metabolism. Genes 2023, 14, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, F.; Yu, D. Jasmonate regulates the inducer of cbf expression-C-repeat binding factor/DRE binding factor1 cascade and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 2907–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Liu, H.; Xiong, L. Endogenous auxin and jasmonic acid levels are differentially modulated by abiotic stresses in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.M.; Cristescu, S.M.; Miersch, O.; Harren, F.J.M.; Wasternack, C.; Mur, L.A.J. Jasmonates act with salicylic acid to confer basal thermotolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.S.; Joo, J.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, Y.K.; Nahm, B.H.; Song, S.I.; Cheong, J.J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, J.K.; Choi, Y.D. OsbHLH148, a basic helix-loop-helix protein, interacts with OsJAZ proteins in a jasmonate signaling pathway leading to drought tolerance in rice. Plant J. 2011, 65, 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhang, N.; Ai, X.; Wang, M.; Huang, Z.; Xiao, L.; Xia, G. A wheat allene oxide cyclase gene enhances salinity tolerance via jasmonate signaling. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, V.; Majee, M. JA shakes hands with ABA to delay seed germination. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 764–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhou, S.; Yang, D.; Fan, Z. Revealing shared and distinct genes responding to JA and SA signaling in Arabidopsis by meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Xin, X.F. Regulation and integration of plant jasmonate signaling: A comparative view of monocot and dicot. J. Genet. Genom. 2022, 49, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, A.; Stintzi, A. Enzymes in jasmonate biosynthesis—Structure, function, regulation. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1532–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilmiller, A.L.; Koo, A.J.K.; Howe, G.A. Functional diversification of acyl-coenzyme A oxidases in jasmonic acid biosynthesis and action. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chini, A.; Monte, I.; Zamarreño, A.M.; Hamberg, M.; Lassueur, S.; Reymond, P.; Weiss, S.; Stintzi, A.; Schaller, A.; Porzel, A.; et al. An OPR3-independent pathway uses 4,5-didehydrojasmonate for jasmonate synthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, G.A.; Major, I.T.; Koo, A.J. Modularity in jasmonate signaling for multistress resilience. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 387–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, H.S.; Song, J.T.; Cheong, J.J.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, Y.W.; Hwang, I.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, Y.D. Jasmonic acid carboxyl methyltransferase: A key enzyme for jasmonate-regulated plant responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 4788–4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbi, V.; Devoto, A. Jasmonate signalling network in Arabidopsis thaliana: Crucial regulatory nodes and new physiological scenarios. New Phytol. 2008, 177, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, B.; Yu, L.; Feng, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, J. Phylogenetic analysis, structural evolution and functional divergence of the 12-oxo-phytodienoate acid reductase gene family in plants. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Christensen, S.; Isakeit, T.; Engelberth, J.; Meeley, R.; Hayward, A.; Emery, R.J.; Kolomiets, M.V. Disruption of OPR7 and OPR8 reveals the versatile functions of jasmonic acid in maize development and defense. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 1420–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, T.; Sobajima, H.; Okada, K.; Chujo, T.; Arimura, S.I.; Tsutsumi, N.; Nishimura, M.; Seto, H.; Nojiri, H.; Yamane, H. Identification of the OsOPR7 gene encoding 12-oxophytodienoate reductase involved in the biosynthesis of jasmonic acid in rice. Planta 2008, 227, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, H.; Wang, H.; Kim, Y.; Song, U.; Tu, M.; Wu, D.; Jiang, L. Creation of male-sterile lines that can be restored to fertility by exogenous methyl jasmonate for the establishment of a two-line system for the hybrid production of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Wang, M.; Xu, F.; Quan, T.; Peng, K.; Xiao, L.; Xia, G. Wheat oxophytodienoate reductase gene TaOPR1 confers salinity tolerance via enhancement of abscisic acid signaling and reactive oxygen species scavenging. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Zheng, J.; Hou, W.; Wang, G.; Wang, J. Overexpression of ZmOPR1 in Arabidopsis enhanced the tolerance to osmotic and salt stress during seed germination. Plant Sci. 2008, 174, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y.; Sun, Q.; Miao, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Yan, C.; Yuan, C.; Zhao, X.; Li, C.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of the 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductase gene family in peanut and functional characterization of AhOPR6 in salt stress. Plants 2025, 14, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Moriconi, J.I.; Burguener, G.F.; Gualano, L.D.; Howell, T.; Lukaszewski, A.; Staskawicz, B.; Cho, M.J.; et al. Dosage differences in 12-OXOPHYTODIENOATE REDUCTASE genes modulate wheat root growth. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Chung, C.Y.L.; Li, M.W.; Wong, F.L.; Wang, X.; Liu, A.; Wang, Z.; Leung, A.K.Y.; Wong, T.H.; Tong, S.W.; et al. A reference-grade wild soybean genome. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandillo, N.; Jarquin, D.; Song, Q.; Nelson, R.; Cregan, P.; Specht, J.; Lorenz, A. A population structure and genome-wide association analysis on the USDA soybean germplasm collection. Plant Genome 2015, 8, plantgenome2015.2004.0024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Hu, J.; Fan, L.; Landis, J.B.; Cannon, S.B.; Grimwood, J.; Schmutz, J.; Jackson, S.A.; et al. Phylogenomics of the genus Glycine sheds light on polyploid evolution and life-strategy transition. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Du, H.; Li, P.; Shen, Y.; Peng, H.; Liu, S.; Zhou, G.A.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Shi, M.; et al. Pan-genome of wild and cultivated soybeans. Cell 2020, 182, 162–176.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodstein, D.M.; Shu, S.; Howson, R.; Neupane, R.; Hayes, R.D.; Fazo, J.; Mitros, T.; Dirks, W.; Hellsten, U.; Putnam, N.; et al. Phytozome: A comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1178–D1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyev, V.; Kosarev, P.; Seledsov, I.; Vorobyev, D. Automatic annotation of eukaryotic genes, pseudogenes and promoters. Genome Biol. 2006, 7, S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; et al. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: The conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D265–D268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Bo, Y.; Han, L.; He, J.; Lanczycki, C.J.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: Functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D200–D203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.H.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Williams, N.; Misleh, C.; Li, W.W. MEME: Discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W369–W373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, P.E.; Golicz, A.A.; Scheben, A.; Batley, J.; Edwards, D. Plant pan-genomes are the new reference. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller, F.; Biesgen, C.; Müssig, C.; Altmann, T.; Weiler, E.W. 12-Oxophytodienoate reductase 3 (OPR3) is the isoenzyme involved in jasmonate biosynthesis. Planta 2000, 210, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stintzi, A.; Browse, J. The Arabidopsis male-sterile mutant, opr3, lacks the 12-oxophytodienoic acid reductase required for jasmonate synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 10625–10630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.M.; Sun, S.C.; Zhang, F.M.; Miao, X.X. Identification of genes potentially related to herbivore resistance in OPR3 overexpression rice by microarray analysis. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2015, 92, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, M. Current perspectives on improving soybean performance on saline-alkaline lands. New Crops 2026, 3, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Guan, R.; Bose, J.; Henderson, S.W.; Wege, S.; Qiu, L.; Gilliham, M. Soybean CHX-type ion transport protein GmSALT3 confers leaf Na+ exclusion via a root derived mechanism, and Cl− exclusion via a shoot derived process. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Xue, M.; Ma, H.; Feng, P.; Chen, T.; Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Ding, X.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, J. Wild soybean (Glycine soja) transcription factor GsWRKY40 plays positive roles in plant salt tolerance. Crop J. 2024, 12, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Sun, Y.; Shan, Z.; He, J.; Wang, N.; Gai, J.; Li, Y. Natural variation in the promoter of GsERD15B affects salt tolerance in soybean. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhu, A.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M. Exogenous jasmonic acid can enhance tolerance of wheat seedlings to salt stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014, 104, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesgen, C.; Weiler, E.W. Structure and regulation of OPR1 and OPR2, two closely related genes encoding 12-oxophytodienoic acid-10,11-reductases from Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 1999, 208, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhou, F.; Liu, B.; Feng, D.; He, Y.; Qi, K.; Wang, H.; Wang, J. Comparative characterization, expression pattern and function analysis of the 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductase gene family in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2011, 30, 981–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Simmons, C.; Yalpani, N.; Crane, V.; Wilkinson, H.; Kolomiets, M. Genomic Analysis of the 12-oxo-phytodienoic Acid Reductase gene family of Zea mays. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005, 59, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C.; Song, S. Jasmonates: Biosynthesis, metabolism, and signaling by proteins activating and repressing transcription. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1303–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wei, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Jiao, P.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, S.; Ma, Y.; Guan, S. Metabolomics and transcriptomic analysis revealed the response mechanism of maize to saline-alkali stress. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 5397–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hou, Y.; Zang, J. Salinity survival: Molecular mechanisms and adaptive strategies in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1527952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shu, H.; Lu, D.; Zhang, T.; Li, M.; Guo, J.; Shi, L. Wild soybean cotyledons at the emergence stage tolerate alkali stress by maintaining carbon and nitrogen metabolism, and accumulating organic acids. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Han, Z.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Lin, C.; Ding, X.; Yan, H.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, C. Genome-Wide Identification of the OPR Gene Family in Soybean and Its Expression Pattern Under Salt Stress. Biology 2026, 15, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010032

Han Z, Zhang X, Sun Y, Lin C, Ding X, Yan H, Zhan Y, Zhang C. Genome-Wide Identification of the OPR Gene Family in Soybean and Its Expression Pattern Under Salt Stress. Biology. 2026; 15(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Zhongxu, Xiangchi Zhang, Yanyan Sun, Chunjing Lin, Xiaoyang Ding, Hao Yan, Yong Zhan, and Chunbao Zhang. 2026. "Genome-Wide Identification of the OPR Gene Family in Soybean and Its Expression Pattern Under Salt Stress" Biology 15, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010032

APA StyleHan, Z., Zhang, X., Sun, Y., Lin, C., Ding, X., Yan, H., Zhan, Y., & Zhang, C. (2026). Genome-Wide Identification of the OPR Gene Family in Soybean and Its Expression Pattern Under Salt Stress. Biology, 15(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010032