Chronic Exposure to Niclosamide Disrupts Structure and Metabolism of Digestive Glands and Foot in Cipangopaludina cathayensis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mesocosm Setup

2.2. Niclosamide Exposures

2.3. C. cathayensis Collection and Analysis

2.3.1. Sampling Design

2.3.2. Niclosamide Bioaccumulation Analysis

2.3.3. Nutritional Component Analysis

2.3.4. Histological Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

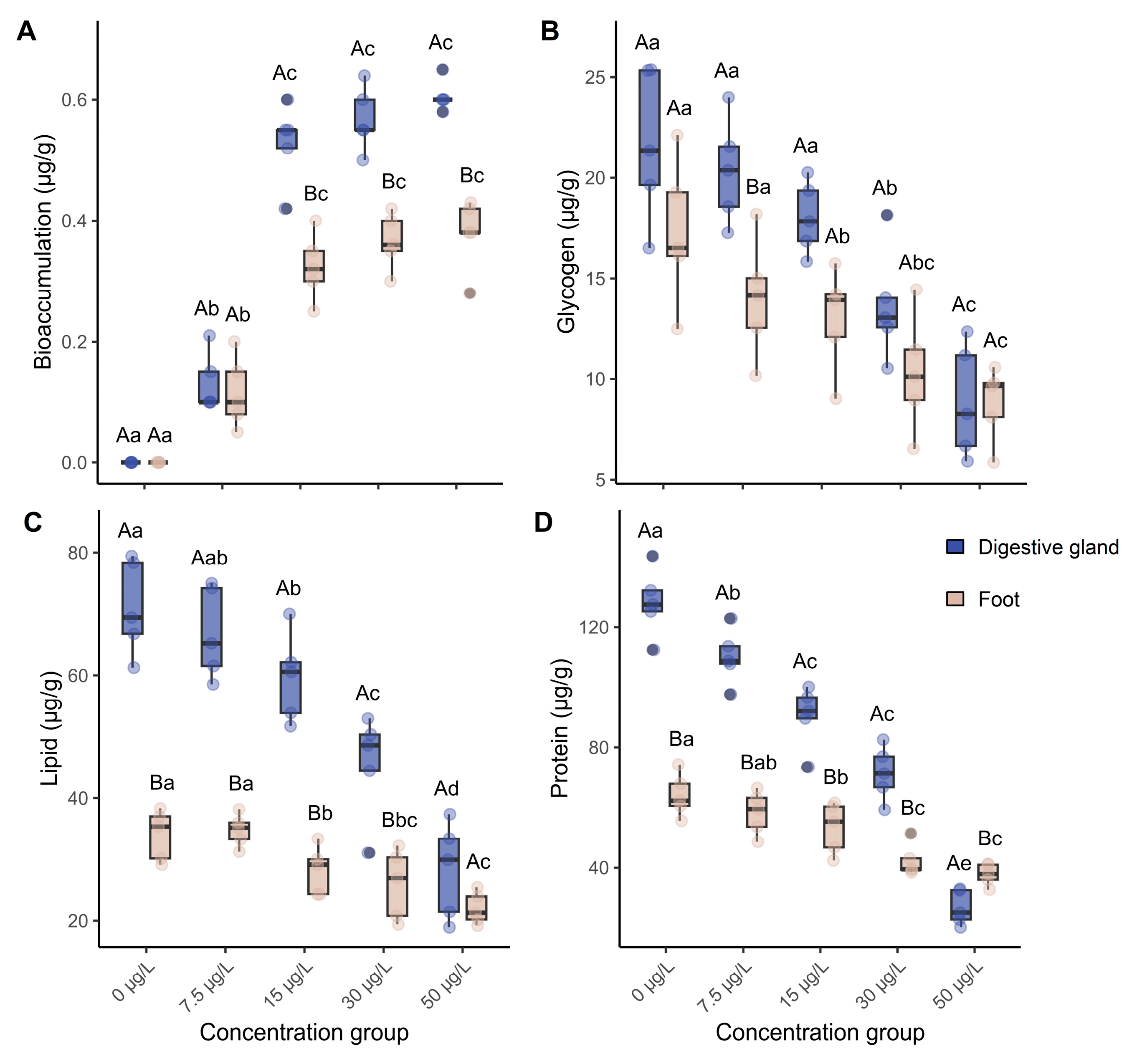

3.1. Niclosamide Bioaccumulation and Nutrient Content Changes

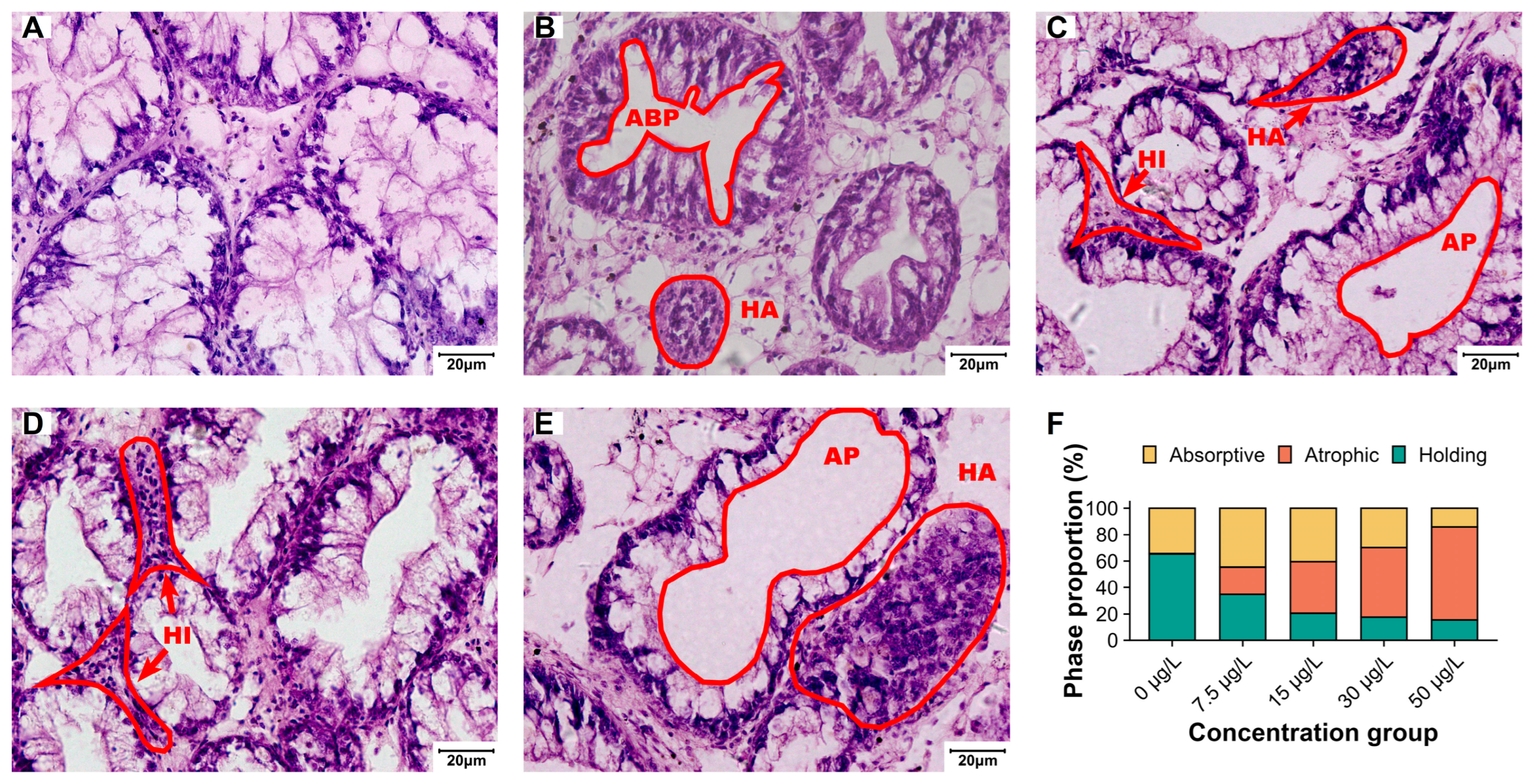

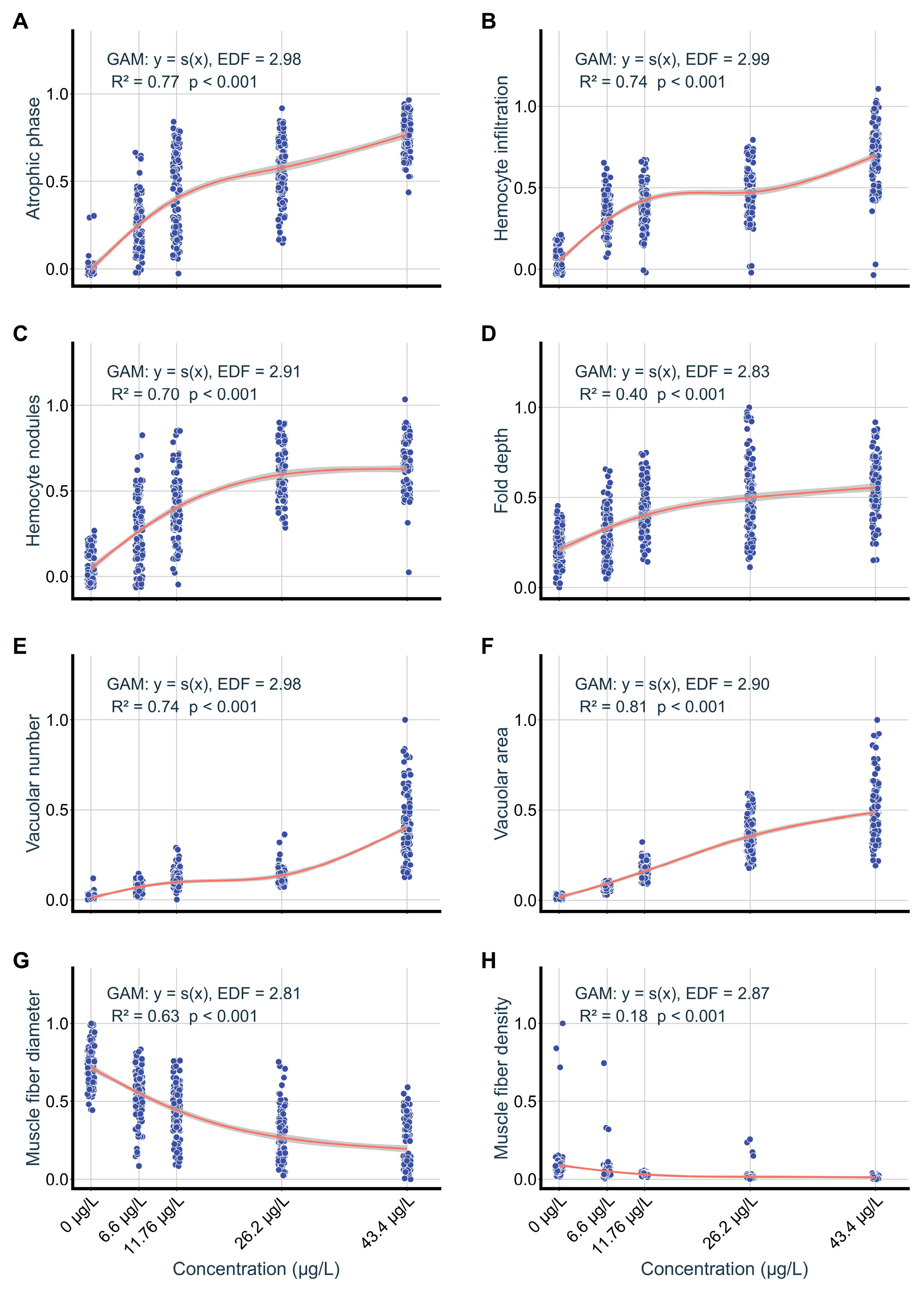

3.2. Structural and Functional Impairment of Digestive Glands

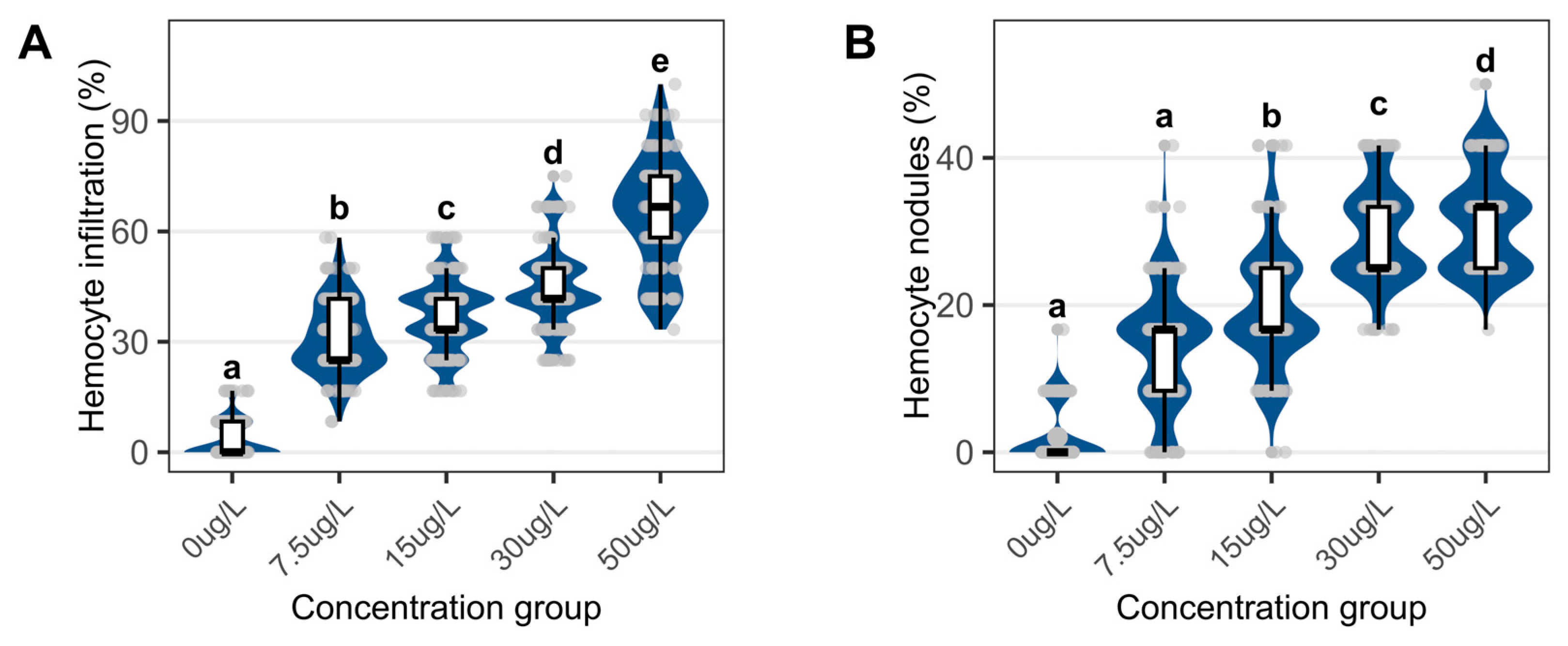

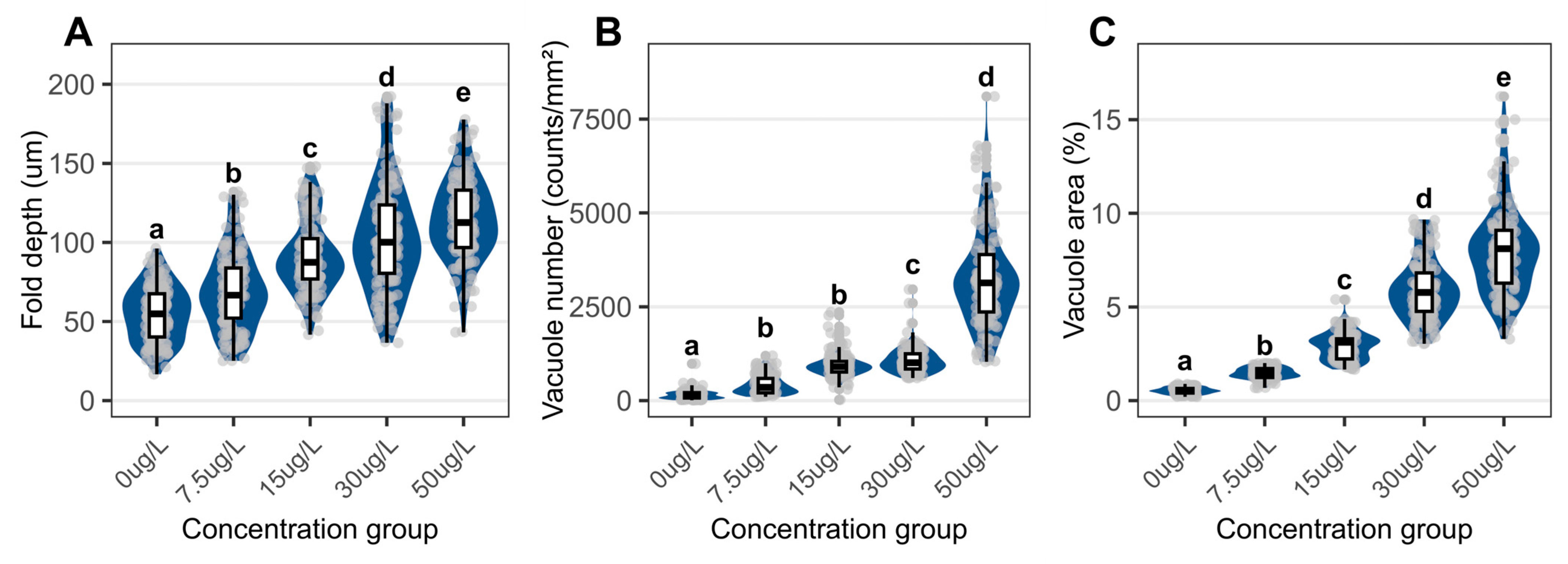

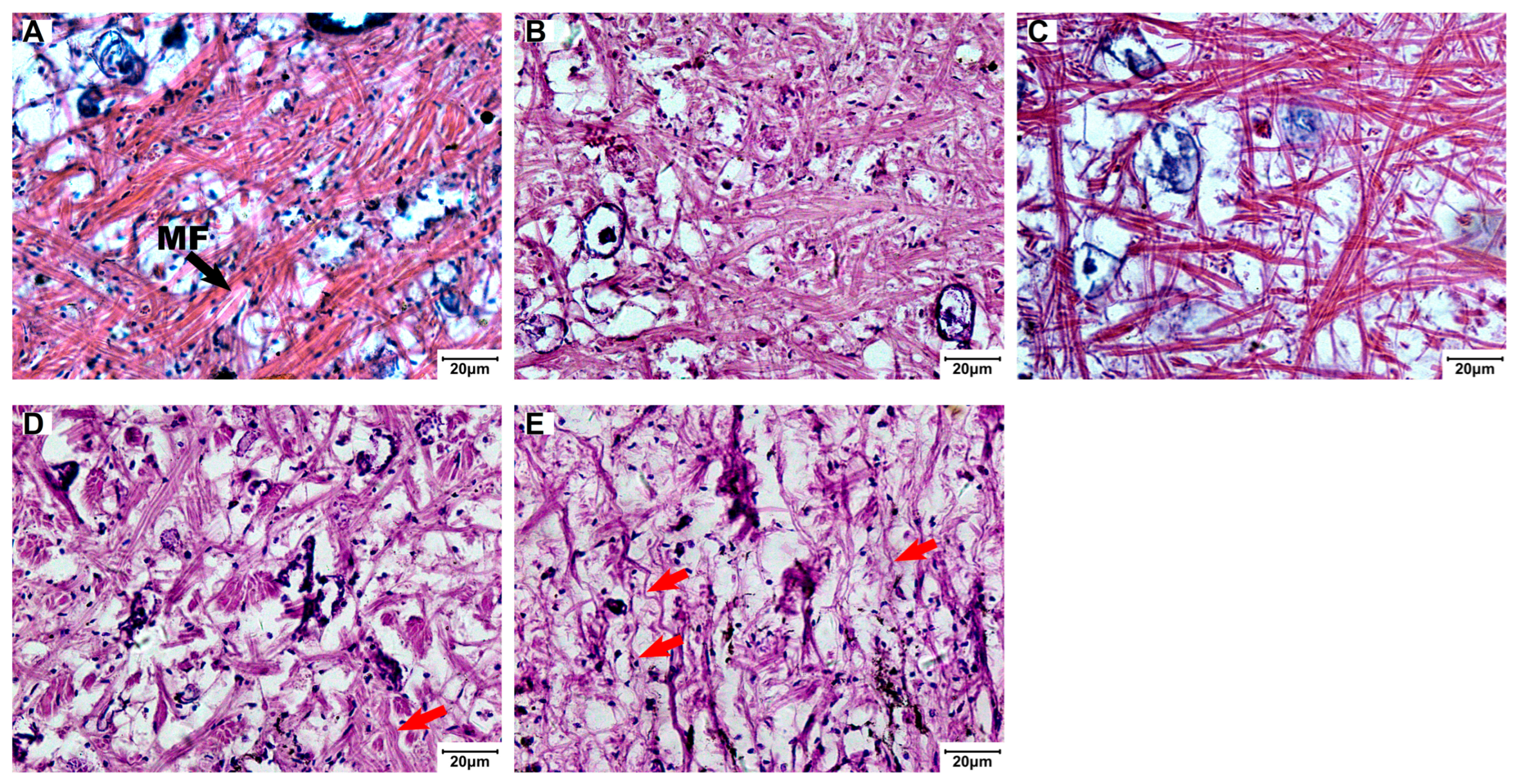

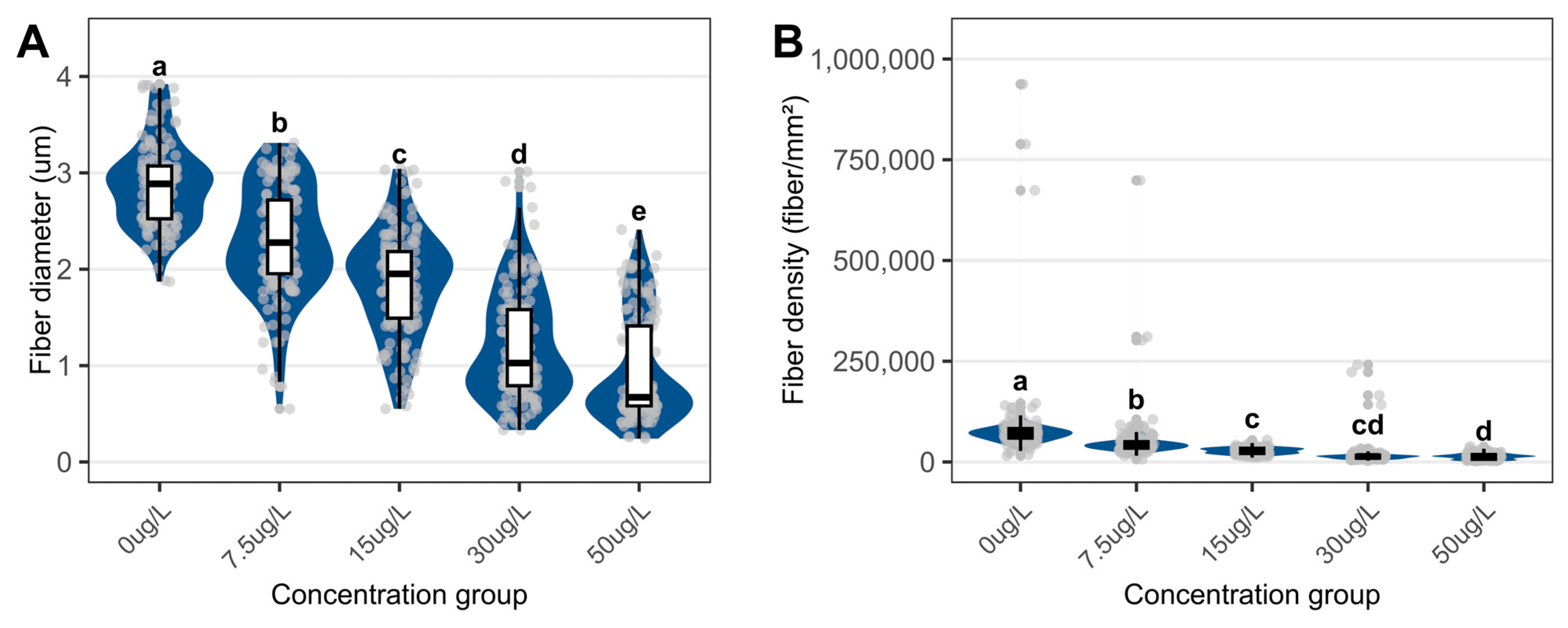

3.3. Structural Changes in Foot

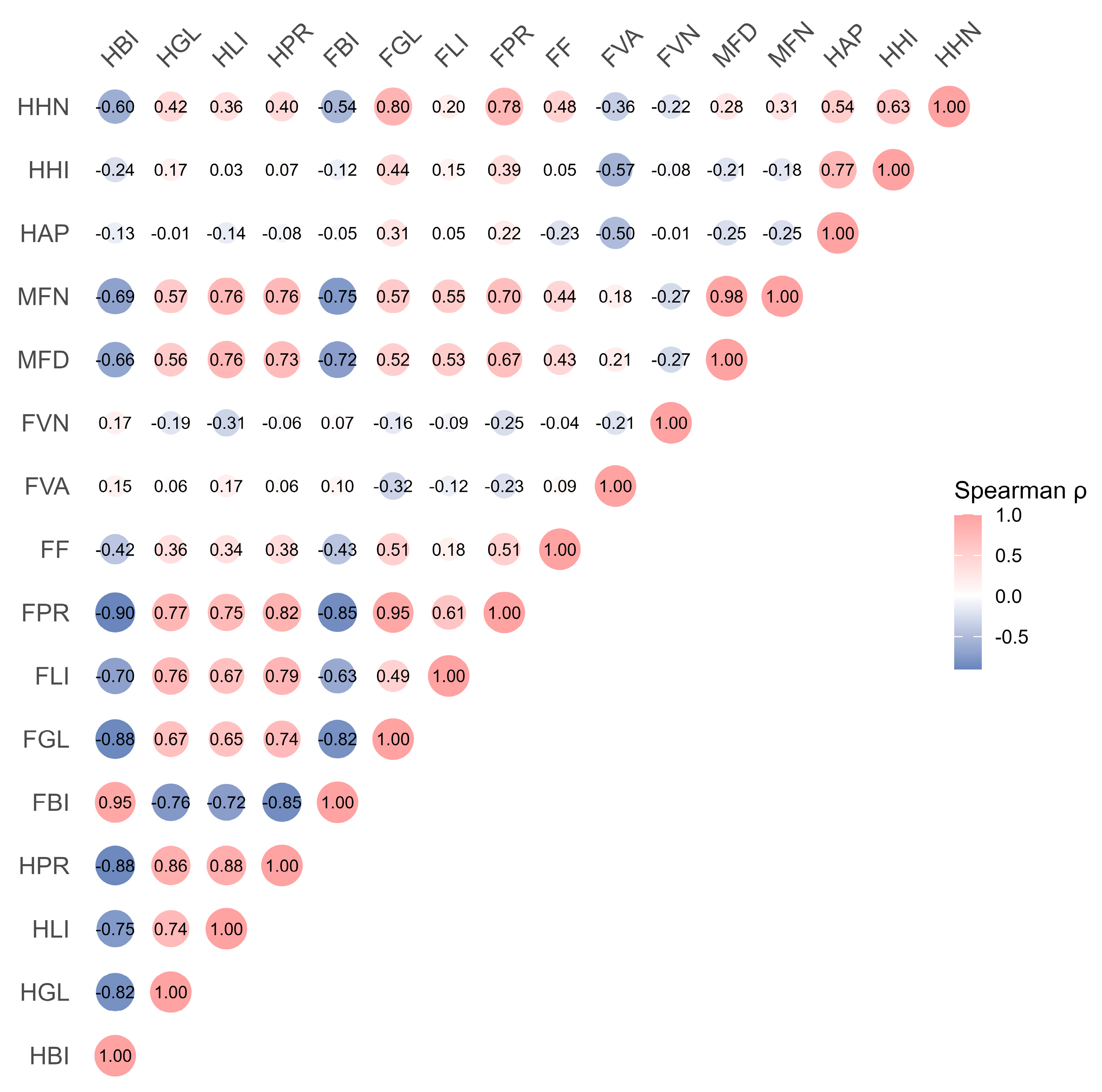

3.4. Relationships Between Niclosamide Exposure, Bioaccumulation, Nutrient Components, and Histopathology

4. Discussion

4.1. Bioaccumulation of Niclosamide

4.2. Structural and Functional Impairment of Digestive Glands Induced by Niclosamide

4.3. Structural and Metabolic Pathologies in the Foot Induced by Niclosamide

4.4. Ecological Impacts of Niclosamide Exposure

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haider, F.; Sokolov, E.P.; Sokolova, I.M. Effects of mechanical disturbance and salinity stress on bioenergetics and burrowing behavior of the soft-shell clam Mya arenaria. J. Exp. Biol. 2018, 221, jeb172643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.G.; Zhen, J.H.; Quan, S.Q.; Liu, M.; Liu, L. Risk assessment for niclosamide residues in water and sediments from Nan Ji Shan Island within Poyang Lake region, China. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 721, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Shen, Y.H.; Zhang, X.W.; Lin, D.; Xia, P.; Song, M.Y.; Yan, L.; Zhong, W.J.; Guo, X.; Wang, C.; et al. Effect-directed analysis based on the reduced human transcriptome (RHT) to identify organic contaminants insource and tap waters along the Yangtze River. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 7840–7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.Q.; Xu, K.F.; Chou, L.B.; Cui, Q.; Hu, G.J.; Zhang, B.B.; Tu, K.; Luo, W.R.; Ma, L.Y.; Guo, J.; et al. Mechanism directed toxicity testing and instrumental analysis make key toxicant identification more targeted and efficient: A case in the Yangtze River. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 11985–11994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, E.C.; Paumgartten, F.J.R. Toxicity of Euphorbia milli latex and niclosamide to snails and nontarget aquatic species. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2000, 46, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumagai, T.; Miyamoto, M.; Koseki, Y.; Imai, Y.; Ishino, T. Development of a spirulina feed effective only for the two larval stages of Schistosoma mansoni, not the intermediate host mollusc. Trop. Med. Health 2025, 53, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.P.; Huang, Y.T.; Lu, Z.H.; Ma, Y.Q.; Ran, X.; Yan, X.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, X.Y.; Luo, L.Y.; Yue, G.Z.; et al. Sublethal effects of niclosamide on the aquatic snail Pomacea canaliculata. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 259, 115064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, A.L.; Cosenza-Contreras, M.; DeMarco, R.; Neves, L.X.; Mattei, B.; Silva, G.G.; Magalhaes, P.H.V.; de Andrade, M.H.G.; Castro-Borges, W. The golden mussel proteome and its response to niclosamide: Uncovering rational targets for control or elimination. J. Proteom. 2020, 217, 103651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelot, N.; Ladeiro, M.P.; Orquevaux, M.; Chaperon, B.; Pochet, C.; Geffard, A. Effects of chemicals on mobility in the bivalve mollusc Dreissena polymorpha. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 286, 107482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, C.L.; Hopper, G.W.; Kreeger, D.A.; Lopez, J.; Maine, A.N.; Brandon, J.S.; Schwalb, A.; Vaughn, C.C. Gains and gaps in knowledge surrounding freshwater mollusk ecosystem services. Freshw. Mollusk Biol. Conserv. 2023, 26, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo-da-Cunha, A. Structure and function of the digestive system in molluscs. Cell Tissue Res. 2019, 377, 475–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroudi, F.; Al Alam, J.; Fajloun, Z.; Millet, M. Snail as sentinel organism for monitoring the environmental pollution; a review. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 113, 106240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shenawy, N.S.; Moawad, T.I.S.; Mohallal, M.E.; Abdel-Nabi, I.M.; Taha, I.A. Histopathologic biomarker response of clam, Ruditapes decussates, to organophosphorous pesticides reldan and roundup: A laboratory study. Ocean Sci. J. 2009, 44, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stara, A.; Pagano, M.; Capillo, G.; Fabrello, J.; Sandova, M.; Albano, M.; Zuskova, E.; Velisek, J.; Matozzo, V.; Faggio, C. Acute effects of neonicotinoid insecticides on Mytilus galloprovincialis: A case study with the active compound thiacloprid and the commercial formulation calypso 480 SC. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 203, 110980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uluturhan, E.; Darilmaz, E.; Kontas, A.; Bilgin, M.; Alyuruk, H.; Altay, O.; Sevgi, S. Seasonal variations of multi-biomarker responses to metals and pesticides pollution in M. galloprovincialis and T. decussatus from Homa Lagoon, Eastern Aegean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 141, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiralj, Z.; Dragun, Z.; Lajtner, J.; Trgovcic, K.; Pavin, T.M.; Busic, B.; Ivankovic, D. Changes in subcellular responses in the digestive gland of the freshwater mussel Unio crassu from a historically contaminated environment. Fishes 2025, 10, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Wang, W.S.; Sanogo, B.; Zeng, X.; Sun, X.; Lv, Z.Y.; Yuan, D.J.; Duan, L.P.; Wu, Z.D. Molluscicidal activity and mechanism of toxicity of a novel salicylanilide ester derivative against Biomphalaria species. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erk, M.; Ivankovic, D.; Strizak, Z. Cellular energy allocation in mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) from the stratified estuary as a physiological biomarker. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yuan, X.P.; He, Y.; Gao, J.; Xie, M.; Xie, Z.G.; Song, R.; Ou, D.S. Niclosamide subacute exposure alters the immune response and microbiota of the gill and gut in black carp larvae, Mylopharyngodon piceus. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 279, 116512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd Elkader, H.T.; Al-Shami, A.S. Microanatomy and behaviour of the date mussel’s adductor and foot muscles after chronic exposure to bisphenol A, with inhibition of ATPase enzyme activities and DNA damage. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C-Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 271, 109684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canli, E.G.; Baykose, A.; Uslu, L.H.; Canli, M. Changes in energy reserves and responses of some biomarkers in freshwater mussels exposed to metal-oxide nanoparticles. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 98, 104077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.Y.; Shang, Y.Y.; Chen, H.D.; Khadka, K.; Pan, Y.T.; Hu, M.H.; Wang, Y.J. Perfluorooctanoate and nano titanium dioxide impair the byssus performance of the mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 134062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, M. Locomotion: The Cost of gastropod crawling. Science 1980, 208, 1288–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.M.; Xu, Y.F.; Wang, Y.Q.; Shi, X.; Zheng, G.H.; Li, Y.F. Starvation shrinks the mussel foot secretory glands and impairs the byssal attachment. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1040466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, F.; Sokolov, E.P.; Timm, S.; Hagemann, M.; Rayon, E.B.; Marigomez, I.; Izagirre, U.; Sokolova, I.M. Interactive effects of osmotic stress and burrowing activity on protein metabolism and muscle capacity in the soft shell clam Mya arenaria. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A-Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2019, 228, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, M.; Furukawa, F.; Kaga, Y.; Funayama, S.; Furukawa, S.; Baba, O.; Lin, C.C.; Hwang, P.P.; Moriyama, S.; Okumura, S. Gluconeogenesis and glycogen metabolism during development of Pacific abalone, Haliotis discus hannai. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2020, 318, R619–R633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.F.; Du, L.N.; Li, Z.Q.; Chen, X.Y.; Yang, J.X. Morphological analysis of the Chinese Cipangopaludina species (Gastropoda; Caenogastropoda: Viviparidae). Dongwuxue Yanjiu 2014, 35, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, X.R.; Wang, J.L.; Hao, S.Y.; Sun, X.B. Three-dimensional synergistic mechanism ofphysical injury, microbiota dysbiosis, and gene transfer in the gut of Cipangopaludina cathayensisunder microplastics and roxithromycin exposure. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Lei, D.N.; Guo, Y.H.; Yang, L.M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.Z.; Lv, S.; Hu, W.; Chen, N.S.; Zhou, X.N. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Oncomelania hupensis: The intermediate snail host of Schistosoma japonicum. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2024, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siefkes, M.J. Use of physiological knowledge to control the invasive sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) in the Laurentian Great Lakes. Conserv. Physiol. 2017, 5, cox031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glüge, J.; Escher, B.; Scheringer, M. How error-prone bioaccumulation experiments affect the risk assessment of hydrophobic chemicals and what could be improved. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2023, 19, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, M.C. Lipid extraction from channel catfish muscle—Comparison of solvent systems. J. Food Sci. 1993, 58, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.C.; Caixeta, M.B.; Ribeiro, G.S.; Silva, L.D.; Araujo, O.A.; Rocha, T.L. Differential bioaccumulation and histopathological changes induced by iron oxide nanoparticles and ferric chloride in the neotropical snail Biomphalaria glabrata. Chemosphere 2025, 371, 144065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, L.P. Evaluation of published bioconcentration factor (BCF) and bioaccumulation factor (BAF) data for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances across aquatic species. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 1530–1543, Correction in Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 2935–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, E.J.; Miller, D.L.; Simpson, G.L.; Ross, N. Hierarchical generalized additive models in ecology: An introduction with mgcv. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.Q.; Ye, X.; Lu, T.; Yang, Y.X.; Sun, B.W.; Xiao, H. Integrated plasma metabolomics and lipidomics profiling highlight distinctive signatures with hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.L.; Yang, S.Y.; Zhu, B.R.; Zhang, M.Y.; Zheng, N.; Hua, J.H.; Li, R.W.; Han, J.; Yang, L.H.; Zhou, B.S. Effects of environmentally relevant concentrations of niclosamide on lipid metabolism and steroid hormone synthesis in adult female zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 910, 168737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.C.V.A.; dos-Santos, J.A.A.; Faria, R.X. Ecotoxicity assays in the evaluation of molluskicidal agents from natural products in freshwater mollusks of medical importance: Lack of information and the choice of tested organisms. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromat. 2025, 24, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sole, M.; Freitas, R.; Rivera-Ingraham, G. The use of an in vitro approach to assess marine invertebrate carboxylesterase responses to chemicals of environmental concern. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 82, 103561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Wu, H.; Gao, J.W.; Jiang, W.M.; Tian, X.; Xie, Z.G.; Zhang, T.; Feng, J.; Song, R. Niclosamide exposure disrupts antioxidant defense, histology, and the liver and gut transcriptome of Chinese soft-shelled turtle (Pelodiscu sinensis). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 260, 115081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yuan, X.P.; Xie, M.; Gao, J.W.; Xiong, Z.Z.; Song, R.; Xie, Z.G.; Ou, D.S. The impact of niclosamide exposure on the activity of antioxidant enzymes and the expression of glucose and lipid metabolism genes in black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus). Genes 2023, 14, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juranic, I.O.; Drakulic, B.J.; Petrovic, S.D.; Mijin, D.Z.; Stankovic, M.V. A QSAR study of acute toxicity of N-substituted fluoroacetamides to rats. Chemosphere 2006, 62, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul-Clark, M.J.; Gilroy, D.W.; Willis, D.; Willoughby, D.A.; Tomlinson, A. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitors have opposite effects on acute inflammation depending on their route of administration. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.Y.; Lee, J.; Park, C.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, G. Curcumin attenuates the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated BV2 microglia. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2007, 28, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malley, D.F.; Klaverkamp, J.F.; Brown, S.B.; Chang, P.S.S. Increase in metallothionein in freshwater mussels Anodonta grandis grandis exposed to cadmium in the laboratory and the field. Water Qual. Res. J. 1993, 28, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi, M.V.; Mastrodonato, M.; Semeraro, D.; Mentino, D.; Capriello, T.; La Pietra, A.; Giarra, A.; Scillitani, G.; Ferrandino, I. Aluminum exposure alters the pedal mucous secretions of the chocolate-band snail, Eobania vermiculata (Gastropoda: Helicidae). Microsc. Res. Tech. 2024, 87, 1453–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, O.A.; Asran, A.A.; Khider, F.K.; El-Shahawy, G.; Abdel-Tawab, H.; Elfayoumi, H.M.K. Efficacy of biopesticide Protecto (Bacillus thuringiensis) (BT) on certain biochemical activities and histological structures of land snail Monacha cartusiana (Muller, 1774). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2022, 32, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, A.A.; Ayyad, M.A.; Mohamedbakr, H.G.; Soliman, U.A.; Almashnowi, M.Y.; Pan, J.H.; Helmy, E.T. Green magnetically separable molluscicide Ba-Ce-Cu ferrite/TiO2 nanocomposite for controlling terrestrial gastropods Monacha Cartusiana. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.G.; Yu, K.; Huang, C.J.; Yu, L.Q.; Zhu, B.Q.; Lam, P.K.S.; Lam, J.C.W.; Zhou, B.S. Prenatal transfer of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) results in developmental neurotoxicity in zebrafish larvae. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 9727–9734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gendy, K.S.; Gad, A.F.; Radwan, M.A. Physiological and behavioral responses of land molluscs as biomarkers for pollution impact assessment: A review. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vliet, S.M.F.; Dasgupta, S.; Sparks, N.R.L.; Kirkwood, J.S.; Vollaro, A.; Hur, M.; zur Nieden, N.I.; Volz, D.C. Maternal-to-zygotic transition as a potential target for niclosamide during early embryogenesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 380, 114699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Ye, J.; Wang, T.; Xu, S.; Ge, G. Chronic Exposure to Niclosamide Disrupts Structure and Metabolism of Digestive Glands and Foot in Cipangopaludina cathayensis. Biology 2026, 15, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010102

Zhang Y, Liu Y, Cai Q, Ye J, Wang T, Xu S, Ge G. Chronic Exposure to Niclosamide Disrupts Structure and Metabolism of Digestive Glands and Foot in Cipangopaludina cathayensis. Biology. 2026; 15(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yanan, Yizhen Liu, Qiying Cai, Jun Ye, Tao Wang, Sheng Xu, and Gang Ge. 2026. "Chronic Exposure to Niclosamide Disrupts Structure and Metabolism of Digestive Glands and Foot in Cipangopaludina cathayensis" Biology 15, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010102

APA StyleZhang, Y., Liu, Y., Cai, Q., Ye, J., Wang, T., Xu, S., & Ge, G. (2026). Chronic Exposure to Niclosamide Disrupts Structure and Metabolism of Digestive Glands and Foot in Cipangopaludina cathayensis. Biology, 15(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010102