Enzymatic Antioxidant Defense System of Scots Pine Seedlings Under Conditions of Progressive Manganese Deficiency

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Manganese deficiency per se should not lead to a decrease in total SOD activity, as the activity of Mn-containing SOD isozymes in Scots pine accounts for only 1–4% of total SOD activity [16].

- The absence of oxidative stress in plant organs under Mn deficiency conditions, determined by the lack of an increase in the contents of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxyalkenals in the roots and needles [15] may be attributed to a coordinated increase in the activities of antioxidant enzymes in response to these conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Determining the Contents of Manganese

2.3. Determining of Fresh and Dry Weights and Calculation of Dry Matter Content

2.4. Determining the Activities of Antioxidant Enzymes

2.5. Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) of SOD

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Manganese Content in Plant Organs

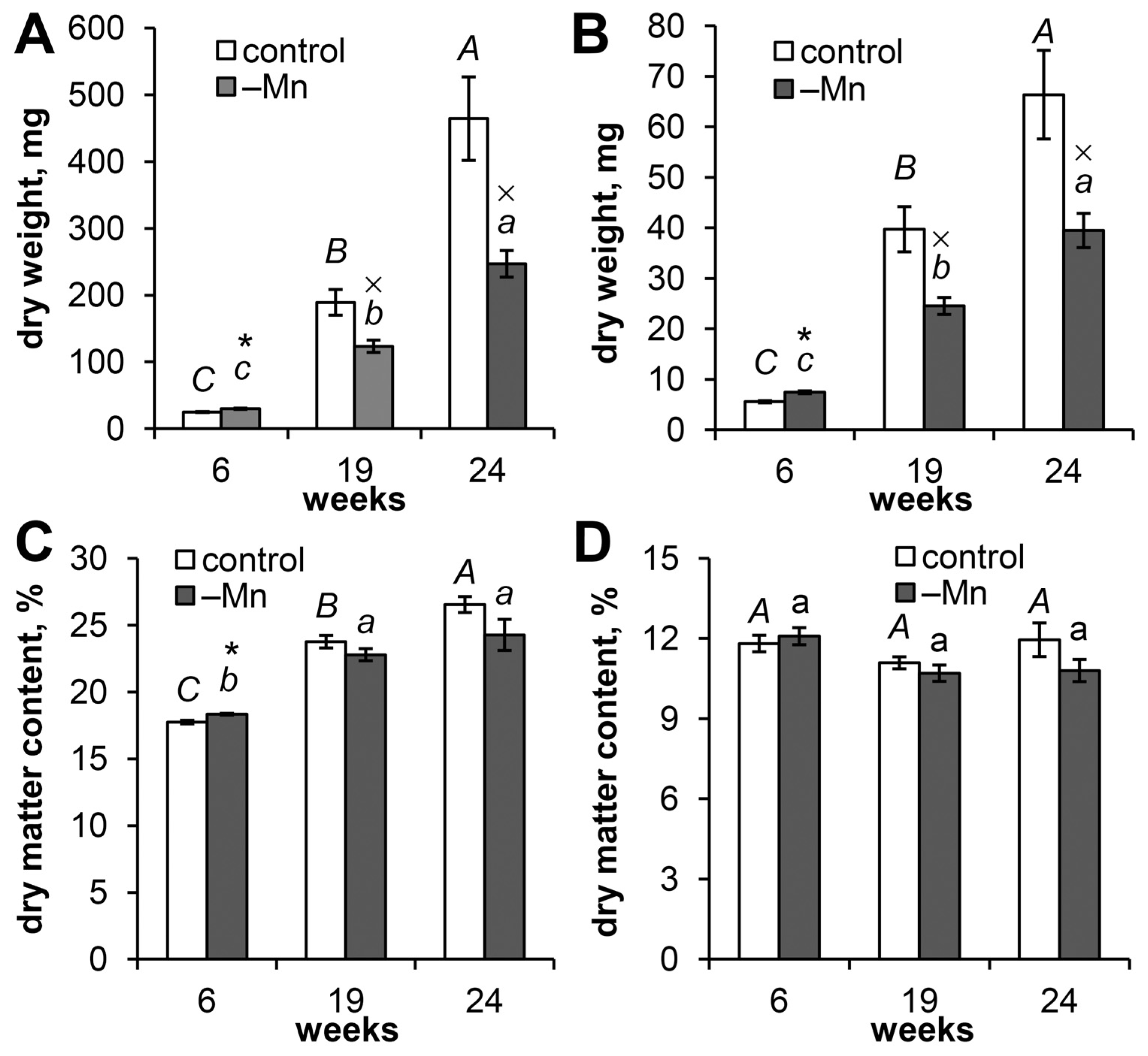

3.2. Effects of Mn Deficiency on Seedling Growth

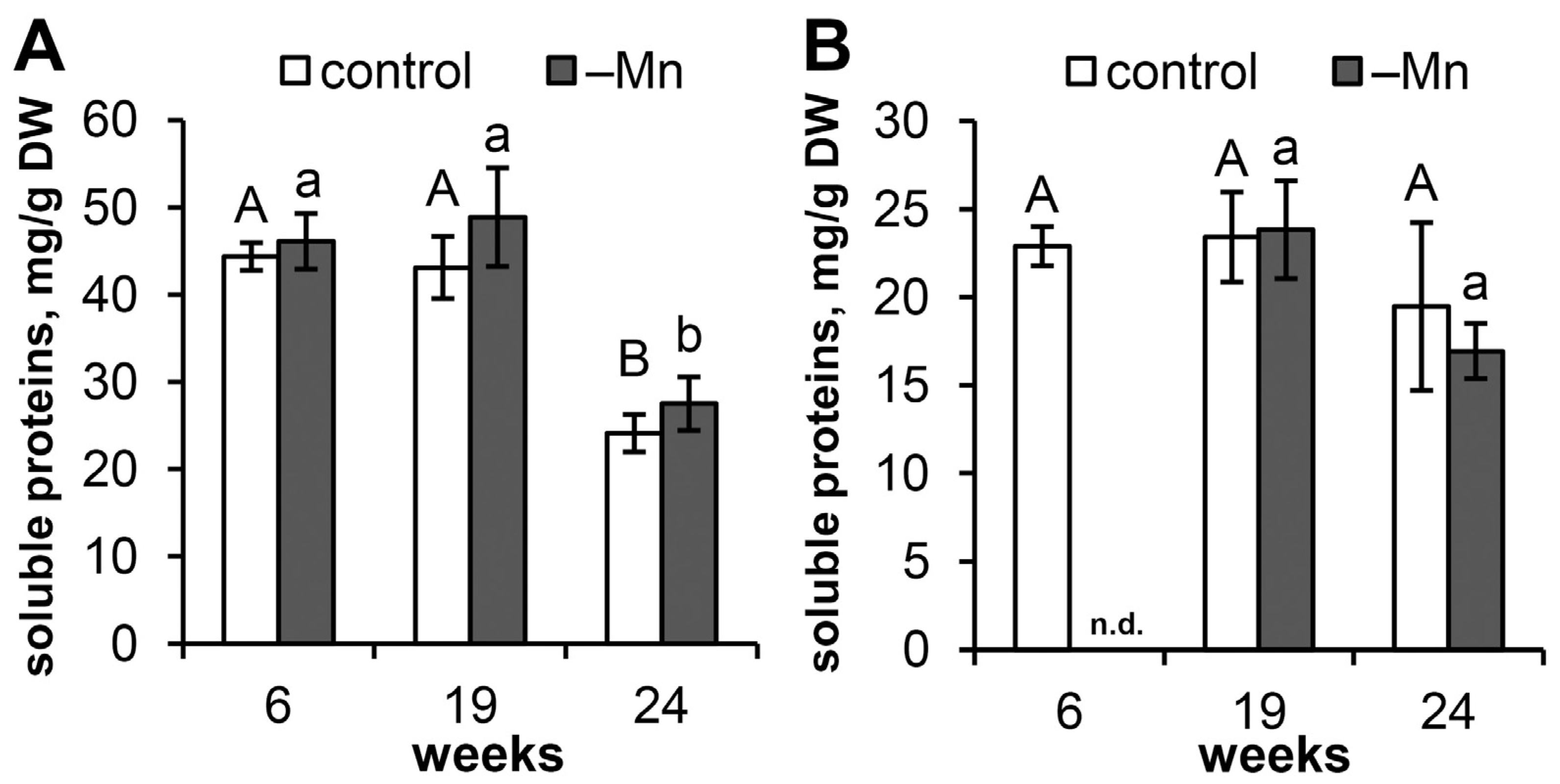

3.3. Soluble Protein Content

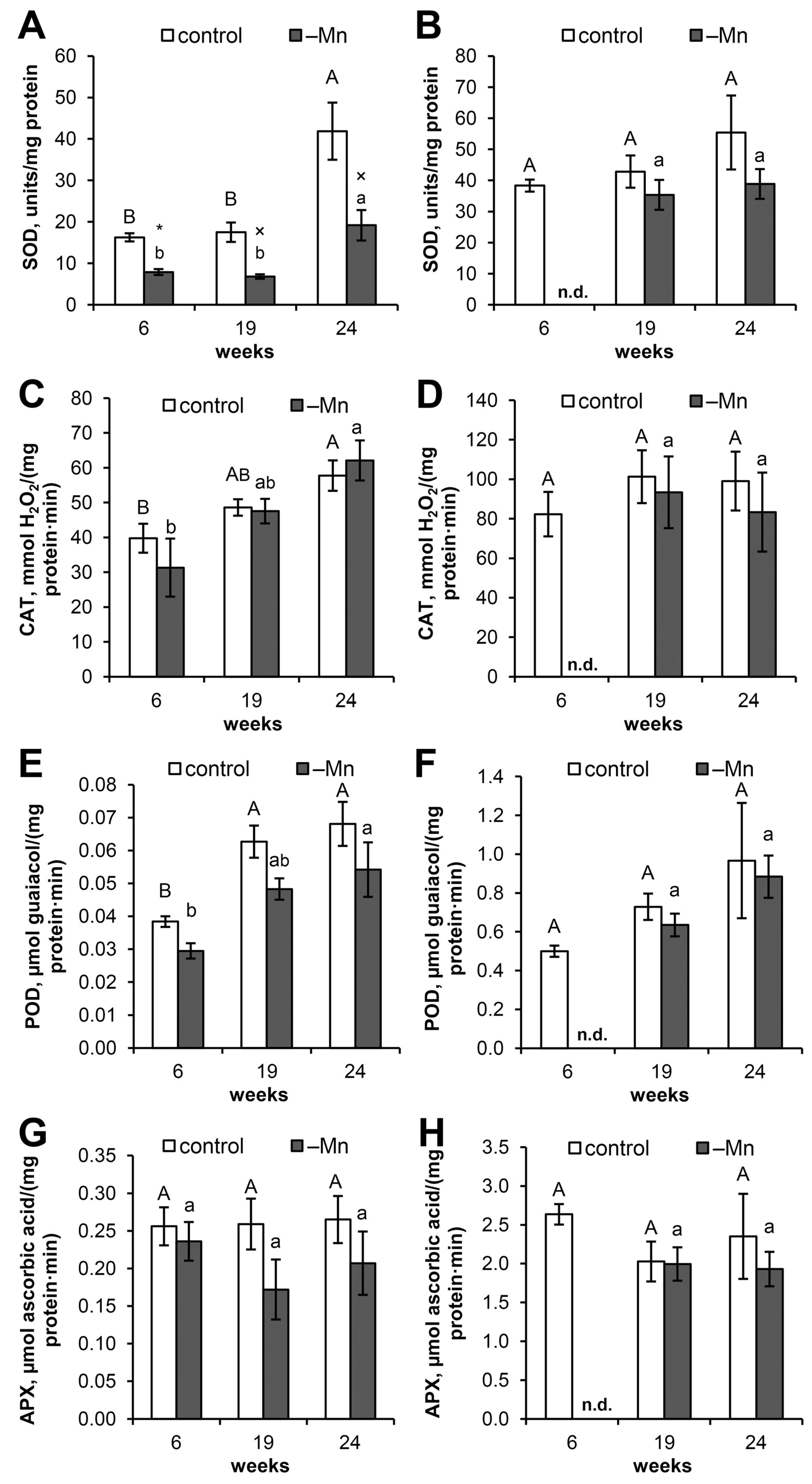

3.4. SOD Activity

3.5. Catalase Activity

3.6. Guaiacol Peroxidase Activity

3.7. Ascorbate Peroxidase Activity

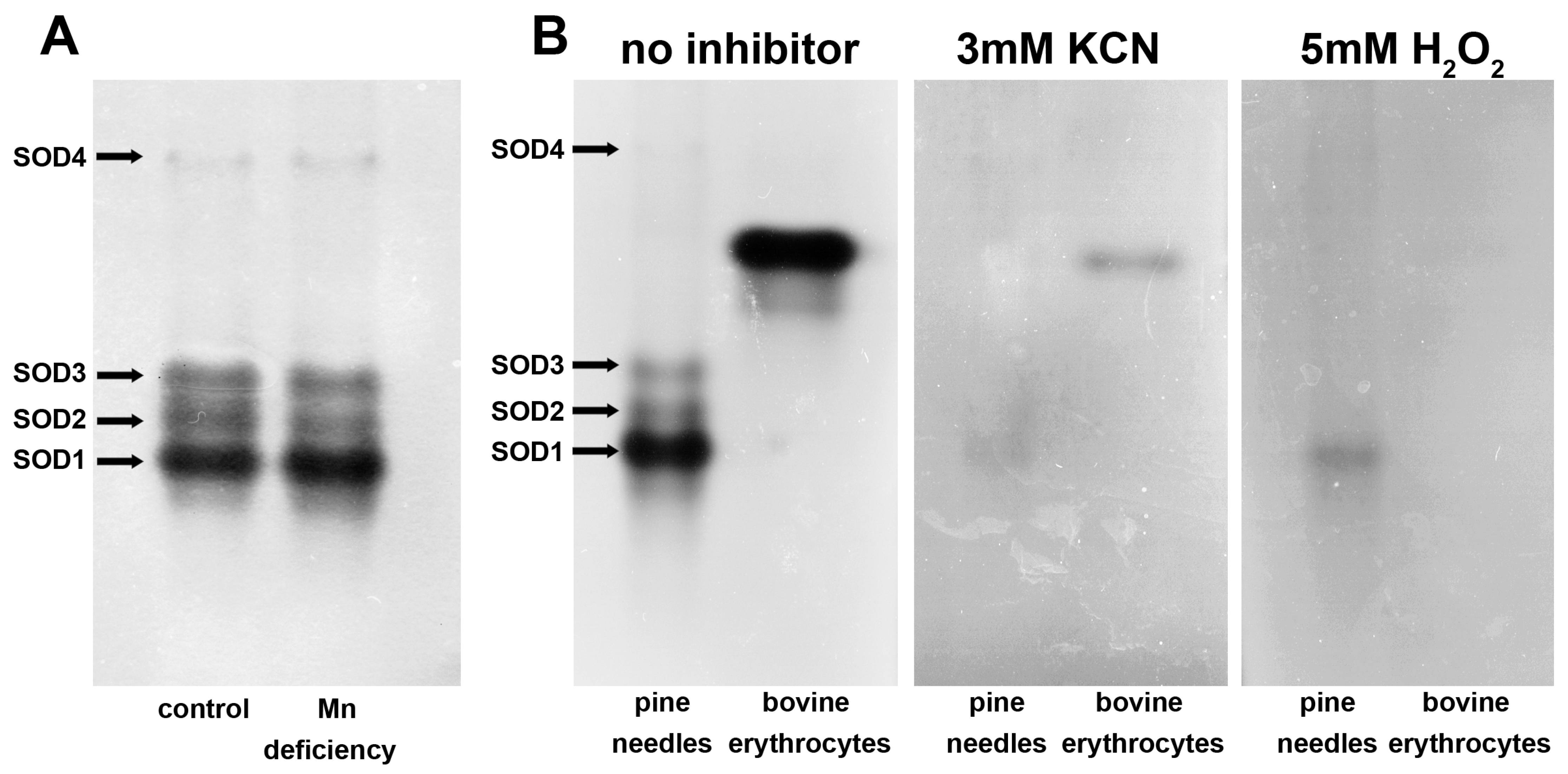

3.8. Native PAGE of SOD

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| PAGE | Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| CAT | Catalase |

| POD | Guaiacol peroxidase |

| APX | ascorbate peroxidase |

| ANOVA | one-way analysis of variance |

References

- Schmidt, S.B.; Husted, S. The Biochemical Properties of Manganese in Plants. Plants 2019, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, S.; Höller, S.; Meier, B.; Peiter, E. Manganese in Plants: From Acquisition to Subcellular Allocation. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, B.; Mariani, O.; Peiter, E. Manganese Handling in Plants: Advances in the Mechanistic and Functional Understanding of Transport Pathways. Quant. Plant Biol. 2025, 6, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, S.B.; Jensen, P.E.; Husted, S. Manganese Deficiency in Plants: The Impact on Photosystem II. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Verma, N.; Tewari, R.K. Micronutrient Deficiency-Induced Oxidative Stress in Plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, C.; van Montagu, M.; Inze, D. Superoxide Dismutase and Stress Tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1992, 43, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Sharma, P. Superoxide Dismutases (SODs) and Their Role in Regulating Abiotic Stress Induced Oxidative Stress in Plants. In Reactive Oxygen, Nitrogen and Sulfur Species in Plants; Hasanuzzaman, M., Fotopoulos, V., Nahar, K., Fujita, M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 53–88. ISBN 978-1-119-46869-1. [Google Scholar]

- Broadley, M.; Brown, P.; Cakmak, I.; Rengel, Z.; Zhao, F. Chapter 7-Function of Nutrients: Micronutrients. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants (Third Edition); Marschner, P., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 191–248. ISBN 978-0-12-384905-2. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Osborne, L.; Rengel, Z. Micronutrient Deficiency Changes Activities of Superoxide Dismutase and Ascorbate Peroxidase in Tobacco Plants. J. Plant Nutr. 1998, 21, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidi, E.O.; Gómez, M.; De La Guardia, M.D. Evaluation of Catalase and Peroxidase Activity as Indicators of Fe and Mn Nutrition for Soybean. J. Plant Nutr. 1986, 9, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenker, M.; Plessner, O.E.; Tel-Or, E. Manganese Nutrition Effects on Tomato Growth, Chlorophyll Concentration, and Superoxide Dismutase Activity. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanquar, V.; Ramos, M.S.; Lelièvre, F.; Barbier-Brygoo, H.; Krieger-Liszkay, A.; Krämer, U.; Thomine, S. Export of Vacuolar Manganese by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 Is Required for Optimal Photosynthesis and Growth under Manganese Deficiency. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1986–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, R.K.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, P.N. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Responses of Mulberry (Morus alba) Plants Subjected to Deficiency and Excess of Manganese. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2013, 35, 3345–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polle, A.; Chakrabarti, K.; Chakrabarti, S.; Seifert, F.; Schramel, P.; Rennenberg, H. Antioxidants and Manganese Deficiency in Needles of Norway Spruce (Picea abies L.) Trees. Plant Physiol. 1992, 99, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Y.V.; Pashkovskiy, P.P.; Ivanova, A.I.; Kartashov, A.V.; Kuznetsov, V.V. Manganese Deficiency Suppresses Growth and Photosynthetic Processes but Causes an Increase in the Expression of Photosynthetic Genes in Scots Pine Seedlings. Cells 2022, 11, 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingsle, G.; Gardeström, P.; Hällgren, J.-E.; Karpinski, S. Isolation, Purification, and Subcellular Localization of Isozymes of Superoxide Dismutase from Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Needles 1. Plant Physiol. 1991, 95, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Y.V.; Kartashov, A.V.; Ivanova, A.I.; Savochkin, Y.V.; Kuznetsov, V.V. Effects of Zinc on Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Seedlings Grown in Hydroculture. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 102, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.J.; Thompson, K.E.N.; Hodgson, J.G. Specific Leaf Area and Leaf Dry Matter Content as Alternative Predictors of Plant Strategies. New Phytol. 1999, 143, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Min, J.; Wang, Y.; Kronzucker, H.J.; Shi, W. The Role of Plant Growth Regulators in Modulating Root Architecture and Tolerance to High-Nitrate Stress in Tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 864285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashkovskiy, P.; Ivanov, Y.; Ivanova, A.; Kartashov, A.; Zlobin, I.; Lyubimov, V.; Ashikhmin, A.; Bolshakov, M.; Kreslavski, V.; Kuznetsov, V. Effect of Light of Different Spectral Compositions on pro/Antioxidant Status, Content of Some Pigments and Secondary Metabolites and Expression of Related Genes in Scots Pine. Plants 2023, 12, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide Dismutase: Improved Assays and an Assay Applicable to Acrylamide Gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chance, B.; Maehly, A.C. Assay of Catalases and Peroxidases. Methods Biochem. Anal. 1955, 10, 9780470110171. [Google Scholar]

- Mika, A.; Luthje, S. Properties of Guaiacol Peroxidase Activities Isolated from Corn Root Plasma Membranes. Plant Physiol. 2003, 132, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen Peroxide Is Scavenged by Ascorbate-Specific Peroxidase in Spinach Chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, A. A Simple Method for Quantitative, Semiquantitative, and Qualitative Assay of Protein. Anal. Biochem. 1978, 89, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.R.; Reid, H.J.; Sharp, B.L. Tricine-Sds-Page. In Protein Electrophoresis: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, H.P.; Fridovich, I. Inhibition of Superoxide Dismutases by Azide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1978, 189, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climent, J.; San-Martín, R.; Chambel, M.R.; Mutke, S. Ontogenetic Differentiation between Mediterranean and Eurasian Pines (Sect. Pinus) at the Seedling Stage. Trees 2011, 25, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.S. Protein Synthesis by Plants under Stressful Conditions. Handb. Plant Crop Stress 1999, 2, 365–397. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, Y.V.; Savochkin, Y.V.; Kuznetsov, V.V. Scots Pine as a Model Plant for Studying the Mechanisms of Conifers Adaptation to Heavy Metal Action: 2. Functioning of Antioxidant Enzymes in Pine Seedlings under Chronic Zinc Action. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 59, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Y.V.; Kartashov, A.V.; Ivanova, A.I.; Savochkin, Y.V.; Kuznetsov, V.V. Effects of Copper Deficiency and Copper Toxicity on Organogenesis and Some Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Seedlings Grown in Hydroculture. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 17332–17344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Rengel, Z. Micronutrient Deficiency Influences Plant Growth and Activities of Superoxide Dismutases in Narrow-Leafed Lupins. Ann. Bot. 1999, 83, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandy, N.E.; Di Giulio, R.T.; Richardson, C.J. Assay and Electrophoresis of Superoxide Dismutase from Red Spruce (Picea rubens Sarg.), Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda L.), and Scotch Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) A Method for Biomonitoring. Plant Physiol. 1989, 90, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streller, S.; Krömer, S.; Wingsle, G. Isolation and Purification of Mitochondrial Mn-Superoxide Dismutase from the Gymnosperm Pinus sylvestris L. Plant Cell Physiol. 1994, 35, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streller, S.; Wingsle, G. Pinus sylvestris L. Needles Contain Extracellular CuZn Superoxide Dismutase. Planta 1994, 192, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, H.P.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide Dismutase and Peroxidase: A Positive Activity Stain Applicable to Polyacrylamide Gel Electropherograms. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1977, 183, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, M.; Li, N.; Lu, Y.; Hong, F. Effects of Manganese Deficiency on Spectral Characteristics and Oxygen Evolution in Maize Chloroplasts. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2010, 136, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hani, U.; Krieger-Liszkay, A. Manganese Deficiency Alters Photosynthetic Electron Transport in Marchantia Polymorpha. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 215, 109042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, K.; Harimoto, S.; Maekawa, S.; Miyake, C.; Ifuku, K. PSII Photoinhibition as a Protective Strategy: Maintaining an Oxidative State of PSI by Suppressing PSII Activity Under Environmental Stress. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinkel, H.; Streller, S.; Wingsle, G. Multiple Forms of Extracellular Superoxide Dismutase in Needles, Stem Tissues and Seedlings of Scots Pine. J. Exp. Bot. 1998, 49, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gara, L.; de Pinto, M.C.; Tommasi, F. The Antioxidant Systems Vis-à-Vis Reactive Oxygen Species during Plant–Pathogen Interaction. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 41, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czégény, G.; Rácz, A. Phenolic Peroxidases: Dull Generalists or Purposeful Specialists in Stress Responses? J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 280, 153884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polle, A.; Chakrabarti, K. Effects of Manganese Deficiency on Soluble Apoplastic Peroxidase Activities and Lignin Content in Needles of Norway Spruce (Picea abies). Tree Physiol. 1994, 14, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skwarek, M.; Patykowski, J.; Witczak, A. Changes in Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Pinus sylvestris and Larix decidua Seedlings After Melolontha melolontha Attack; Forest Research Institute: Sękocin Stary, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura, K.; Ishikawa, T. Physiological Function and Regulation of Ascorbate Peroxidase Isoforms. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 2700–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organ | 6th Week | 19th Week | 24th Week | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Mn-Deficient | Control | Mn-Deficient | Control | Mn-Deficient | |

| Roots * | 3.17 ± 0.34 A | 0.04 ± 0.01 b, × | 0.41 ± 0.02 B | 0.10 ± 0.01 a, × | 0.71 ± 0.05 AB | 0.10 ± 0.00 a, × |

| Needles * | 5.75 ± 0.21 A | 0.34 ± 0.03 a, × | 6.18 ± 0.63 A | 0.11 ± 0.01 b, × | 5.92 ± 0.55 A | 0.10 ± 0.02 b, × |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ivanov, Y.V.; Ivanova, A.I.; Kartashov, A.V.; Glushko, G.V.; Loginova, P.P.; Kuznetsov, V.V. Enzymatic Antioxidant Defense System of Scots Pine Seedlings Under Conditions of Progressive Manganese Deficiency. Biology 2026, 15, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010101

Ivanov YV, Ivanova AI, Kartashov AV, Glushko GV, Loginova PP, Kuznetsov VV. Enzymatic Antioxidant Defense System of Scots Pine Seedlings Under Conditions of Progressive Manganese Deficiency. Biology. 2026; 15(1):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010101

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvanov, Yury V., Alexandra I. Ivanova, Alexander V. Kartashov, Galina V. Glushko, Polina P. Loginova, and Vladimir V. Kuznetsov. 2026. "Enzymatic Antioxidant Defense System of Scots Pine Seedlings Under Conditions of Progressive Manganese Deficiency" Biology 15, no. 1: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010101

APA StyleIvanov, Y. V., Ivanova, A. I., Kartashov, A. V., Glushko, G. V., Loginova, P. P., & Kuznetsov, V. V. (2026). Enzymatic Antioxidant Defense System of Scots Pine Seedlings Under Conditions of Progressive Manganese Deficiency. Biology, 15(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010101