Dog–Stranger Interactions Can Facilitate Canine Incursion into Wilderness: The Role of Food Provisioning and Sociability

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

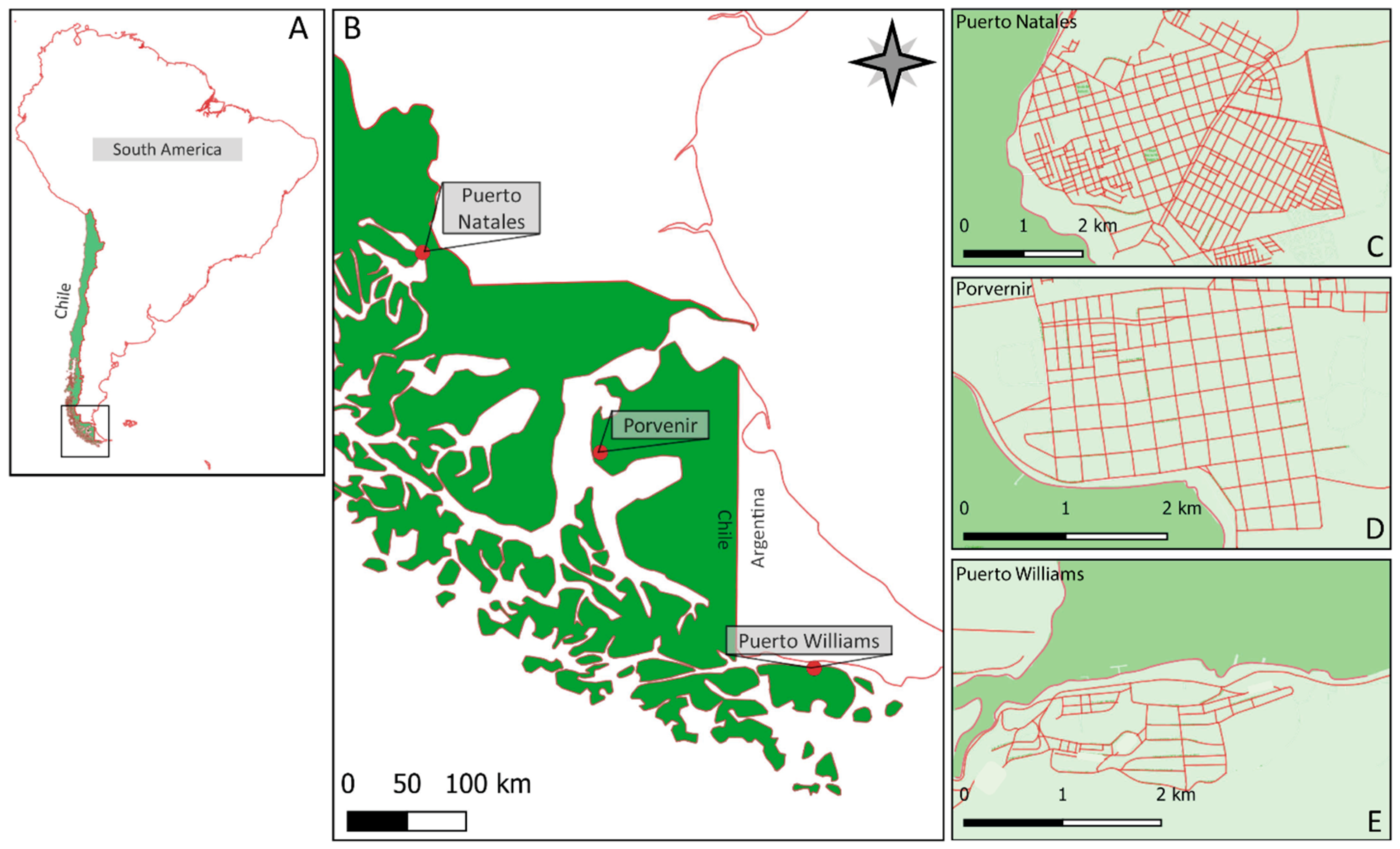

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Ethics Statement

2.3. Participating Dogs

2.4. Experimental Procedure

2.5. Behavioral Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

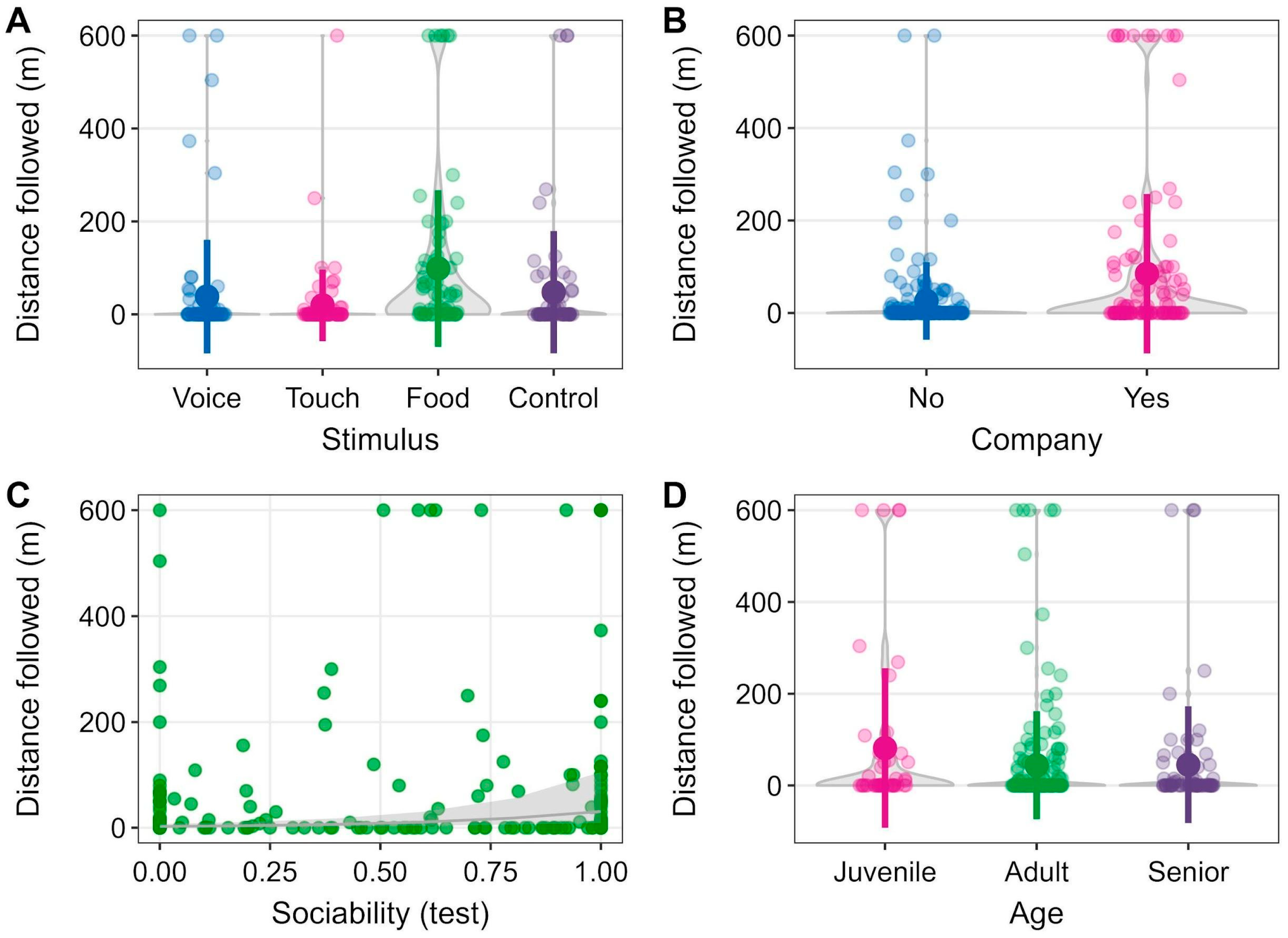

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gompper, M.E. (Ed.) Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, L.A.; Yamamoto, M. Dogs as helping partners and companions for humans. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior and Interactions with People, 2nd ed.; Serpell, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 247–270. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm-Seyfarth, A.; Harms, W.; Berger, A. Detection dogs in nature conservation: A database on their world-wide deployment with a review on breeds used and their performance compared to other methods. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, J.F. Dogs and dog control in developing countries. In The State of the Animals III; Salem, D.J., Rowan, A.N., Eds.; Humane Society Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, T.S.; Dickman, C.R.; Glen, A.S.; Newsome, T.M.; Nimmo, D.G.; Ritchie, E.G.; Vanak, A.T.; Wirsing, A.J. The global impacts of domestic dogs on threatened vertebrates. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 210, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.S.; Glen, A.S.; Nimmo, D.G.; Ritchie, E.G.; Dickman, C.R. Invasive predators and global biodiversity loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11261–11265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanak, A.T.; Gompper, M.E. Dogs (Canis familiaris) as carnivores: Their role and function in intraguild competition. Mammal Rev. 2009, 39, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, C.L.; Le Pendu, Y.; Giné, G.A.; Dickman, C.R.; Newsome, T.M.; Cassano, C.R. Human behaviors determine the direct and indirect impacts of free-ranging dogs on wildlife. J. Mammal. 2018, 99, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, M.; Pelican, K.; Cross, P.; Eguren, A.; Singer, R. Fine-scale movements of rural free-ranging dogs in conservation areas in the temperate rainforest of the coastal range of southern Chile. Mamm. Biol. 2015, 80, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Izaguirre, E.; Van Woersem, A.; Eilers, K.C.H.; Van Wieren, S.E.; Bosch, G.; Van der Zijpp, A.J.; De Boer, I.J.M. Roaming characteristics and feeding practices of village dogs scavenging sea-turtle nests. Anim. Conserv. 2015, 18, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, P.D. The movement, roaming behaviour and home range of free-roaming domestic dogs, Canis lupus familiaris, in coastal New South Wales. Wildl. Res. 1999, 26, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüttler, E.; Saavedra-Aracena, L.; Jiménez, J.E. Spatial and temporal plasticity in free-ranging dogs in sub-Antarctic Chile. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 250, 105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Rodríguez, E.A.; Sieving, K.E. Influence of care of domestic carnivores on their predation on vertebrates. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dürr, S.; Dhand, N.K.; Bombara, C.; Molloy, S.; Ward, M.P. What influences the home range size of free-roaming domestic dogs? Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Aracena, L.; Grimm-Seyfarth, A.; Schüttler, E. Do dog-human bonds influence movements of free-ranging dogs in wilderness? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 241, 105358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.H.; Chang, G.M.; Yu, P.H.; Chen, W.H.; Yen, S.C. The difference in roaming behavior between owned and unowned dogs in a satoyama landscape area. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2025, 283, 106521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G.E.; Conte, A.; Garde, E.J.; Messori, S.; Vanderstichel, R.; Serpell, J. Movement and home range of owned free-roaming male dogs in Puerto Natales, Chile. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 205, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitain, S.; Cimarelli, G.; Blenkuš, U.; Range, F.; Marshall-Pescini, S. Street-wise dog testing: Feasibility and reliability of a behavioural test battery for free-ranging dogs in their natural habitat. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartner, M.C. Pet personality: A review. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2015, 75, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.C.; Gosling, S.D. Temperament and personality in dogs (Canis familiaris): A review and evaluation of past research. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 95, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svartberg, K. Individual differences in behaviour—Dog personality. In The Behavioural Biology of Dogs; Jensen, P., Ed.; Cromwell Press: Trowbridge, UK, 2007; pp. 182–206. [Google Scholar]

- VonHoldt, B.M.; Shuldiner, E.; Koch, I.J.; Kartzinel, R.Y.; Hogan, A.; Brubaker, L.; Wander, S.; Stahler, D.; Wynne, C.D.L.; Ostrander, E.A.; et al. Structural variants in genes associated with human Williams-Beuren syndrome underlie stereotypical hypersociability in domestic dogs. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starling, M.J.; Branson, N.; Thomson, P.C.; McGreevy, P.D. “Boldness” in the domestic dog differs among breeds and breed groups. Behav. Process. 2013, 97, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkó, E.; Kubinyi, E.; Gácsi, M.; Miklósi, Á. Preliminary analysis of an adjective-based dog personality questionnaire developed to measure some aspects of personality in the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 138, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerepesi, A.; Dóka, A.; Miklósi, Á. Dogs and their human companions: The effect of familiarity on dog–human interactions. Behav. Process. 2015, 110, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, D.; Sau, S.; Bhadra, A. Free-ranging dogs understand human intentions and adjust their behavioral responses accordingly. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, D.; Sau, S.; Das, J.; Bhadra, A. Free-ranging dogs prefer petting over food in repeated interactions with unfamiliar humans. J. Exp. Biol. 2017, 220, 4654–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, D.; Sarkar, R.; Sau, S.; Bhadra, A. Sociability of Indian free-ranging dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) varies with human movement in urban areas. J. Comp. Psychol. 2021, 135, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde, E.; Marín-Vial, P.; Pérez, G.E.; Sandvig, E.M. A review and analysis of the national dog population management program in Chile. Animals 2022, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Jamett, G.; Cleaveland, S.; Cunningham, A.A.; Bronsvoort, B.D. Demography of domestic dogs in rural and urban areas of the Coquimbo region of Chile and implications for disease transmission. Prev. Vet. Med. 2010, 94, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schüttler, E.; Saavedra-Aracena, L.; Jiménez, J.E. Domestic carnivore interactions with wildlife in the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve, Chile: Husbandry and perceptions of impact from a community perspective. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrios, C.L.; Bustos-López, C.; Pavletic, C.; Parra, A.; Vidal, M.; Bowen, J.; Fatjó, J. Epidemiology of dog bite incidents in Chile: Factors related to the patterns of human-dog relationship. Animals 2021, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüttler, E.; Klenke, R.; McGehee, S.; Rozzi, R.; Jax, K. Vulnerability of ground-nesting waterbirds to predation by invasive American mink in the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve, Chile. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecino-Latorre, D.; San Martín, W. Evidence supporting that human-subsidized free-ranging dogs are the main cause of animal losses in small-scale farms in Chile. Ambio 2019, 48, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contardo, J.; Grimm-Seyfarth, A.; Cattan, P.E.; Schüttler, E. Environmental factors regulate occupancy of free-ranging dogs on a sub-Antarctic island, Chile. Biol. Invasions 2021, 23, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Rodríguez, E.A.; Cortés, E.I.; Álvarez, X.; Cabeza, D.; Cáceres, B.; Cáceres, B.; Cariñanos, A.; Crego, R.D.; Cisternas, G.; Fernández, R.; et al. A camera-trap assessment of the native and invasive mammals present in protected areas of Magallanes, Chilean Patagonia. Gayana 2024, 88, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Rodríguez, E.A.; Cortés, E.I.; Zambrano, B.; Naughton-Treves, L.; Farías, A.A. On the causes and consequences of the free-roaming dog problem in southern Chile. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüttler, E.; Jiménez, J.E. Are tourists facilitators of the movement of free-ranging dogs? Animals 2022, 12, 3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feuerbacher, E.N.; Wynne, C.D. Relative efficacy of human social interaction and food as reinforcers for domestic dogs and hand-reared wolves. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2012, 98, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, D.; Mandal, S.; Shit, P.; Varghese, M.G.; Vishnoi, A.; Bhadra, A. Free-ranging dogs are capable of utilizing complex human pointing cues. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 507348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE (National Statistics Institute Censo) Censo. 2024. Available online: https://censo2024.ine.gob.cl/. (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Bahamonde, R. Muestreo Censal Canino en la Ciudad de Puerto Natales. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Magallanes, Punta Arenas, Chile, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- SUBDERE (Subsecretary of Regional and Administrative Development) Informe Final Evaluación Programas Gubernamentales 2019. Programa Tenencia Responsable de Animales de Compañía. Available online: https://www.dipres.gob.cl/597/articles-189325_informe_final.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- SERNATUR (National Tourism Service) Reporte: Visitas al Sistema Nacional de Áreas Silvestres Protegidas del Estado. Available online: https://datosturismo.sernatur.cl/siet/reporteDinamicoSNASPE (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- SAG (Agricultural and Livestock Service). Statistics of Denunciations of Carnivore Attacks on Regional Livestock. Available online: https://www.portaltransparencia.cl (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Zurita, C.; Oporto, J.; Valverde, I.; Bernales, B.; Soto, N.; Rau, J.R.; Jaksic, F.M. Density, abundance, and activity of the chilla or grey fox (Lycalopex griseus) in Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, Chile. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2024, 97, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Rojas, C.A.; Alvarez, J.F. Reemergence of Echinococcus granulosus infections after 2004 termination of control program in Magallanes region, Chile. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N.D. How old is my dog? Identification of rational age groupings in pet dogs based upon normative age-linked processes. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 643085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerstein, N.L.; Terkel, J. Interrelationships of dogs (Canis familiaris) and cats (Felis catus L.) living under the same roof. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 113, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaroni, M.; Schär, J.; Baxter, E.; Gratalon, J.; Range, F.; Marshall-Pescini, S.; Dale, R. Village dogs match pet dogs in reading human facial expressions. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friard, O.; Gamba, M. BORIS: A free, versatile open-source event-logging software for video/audio coding and live observations. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Schloerke, B.; Cook, D.; Larmarange, J.; Briatte, F.; Marbach, M.; Thoen, E.; Elberg, A.; Crowley, J. GGally: Extension to ‘ggplot2’, R Package Version 2.2.1. Available online: https://ggobi.github.io/ggally/reference/GGally-package.html (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Bartoń, K. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference, R Package Version 1.48.9/r534. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Hartig, F. DHARMa: Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level/Mixed) Regression Models, R Package Version 0.4.7. Available online: https://github.com/florianhartig/dharma (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Min, S.H.; Zhou, J. smplot: An R package for easy and elegant data visualization. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 802894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassambara, A. ggpubr: ’ggplot2’ Based Publication Ready Plots, R Package Version 0.6.0. Available online: https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/ggpubr/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Navedo, J.G.; Verdugo, C.; Rodríguez-Jorquera, I.A.; Abad-Gómez, J.M.; Suazo, C.G.; Castañeda, L.E.; Araya, V.; Ruiz, J.; Gutiérrez, J.S. Assessing the effects of human activities on the foraging opportunities of migratory shorebirds in Austral high-latitude bays. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, E.I.; Navedo, J.G.; Silva-Rodríguez, E.A. Widespread presence of domestic dogs on sandy beaches of southern Chile. Animals 2021, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feuerbacher, E.N.; Wynne, C.D. Shut up and pet me! Domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) prefer petting to vocal praise in concurrent and single-alternative choice procedures. Behav. Process. 2015, 110, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerbacher, E.N.; Wynne, C.D. Most domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) prefer food to petting: Population, context, and schedule effects in concurrent choice. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2014, 101, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhne, F.; Hößler, J.C.; Struwe, R. Effects of human-dog familiarity on dogs’ behavioural responses to petting. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 142, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, D.; Bhadra, A. Adjustment in the point-following behaviour of free-ranging dogs—roles of social petting and informative-deceptive nature of cues. Anim. Cogn. 2022, 25, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gácsi, M.; Topál, J.; Miklósi, Á.; Dóka, A.; Csányi, V. Behavior of adult dogs (Canis familiaris) living at rescue centers: Forming new bonds. J. Comp. Psychol. 2001, 115, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerbacher, E.N.; Wynne, C.D. Dogs don’t always prefer their owners and can quickly form strong preferences for certain strangers over others. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2017, 108, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, S.; Chakraborty, M.; Lahiri, A.; Gope, H.; Bhaduri, S.K.; Bhadra, A. Free-ranging dogs quickly learn to recognize a rewarding person. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 278, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starling, M.J.; Branson, N.; Thomson, P.C.; McGreevy, P.D. Age, sex and reproductive status affect boldness in dogs. Vet. J. 2013, 197, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coren, S. The Intelligence of Dogs: A Guide to the Thoughts, Emotions, and Inner Lives of Our Canine Companions, revised ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudet, R.; Chalifoux, A.; Dallaire, A. Predictive value of activity level and behavioral evaluation on future dominance in puppies. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1994, 40, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svartberg, K. A comparison of behaviour in test and in everyday life: Evidence of three consistent boldness-related personality traits in dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 91, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde, E.; Pérez, G.E.; Vanderstichel, R.; Dalla Villa, P.F.; Serpell, J.A. Effects of surgical and chemical sterilization on the behavior of free-roaming male dogs in Puerto Natales, Chile. Prev. Vet. Med. 2016, 123, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimarelli, G.; Juskaite, M.; Range, F.; Marshall-Pescini, S. Free-ranging dogs match a human’s preference in a foraging task. Curr. Zool. 2024, 70, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vas, J.; Topál, J.; Gácsi, M.; Miklósi, A.; Csányi, V. A friend or an enemy? Dogs’ reaction to an unfamiliar person showing behavioural cues of threat and friendliness at different times. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 94, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, C.A.; Lüders, C.F.; Manterola, C.; Velazco, M. La pérdida de la percepción al riesgo de zoonosis y la figura del perro comunitario. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 2018, 35, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanni, R.; Natoli, E.; Cafazzo, S.; Valsecchi, P. Free-ranging dogs assess the quantity of opponents in intergroup conflicts. Anim. Cogn. 2011, 14, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, M.; Bhadra, A. The great Indian joint families of free-ranging dogs. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.S.; Bhadra, A.; Ghosh, A.; Mitra, S.; Bhattacharjee, D.; Chatterjee, J.; Nandi, A.K.; Bhadra, A. To be or not to be social: Foraging associations of free-ranging dogs in an urban ecosystem. Acta Ethol. 2014, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.D.; Zhai, W.; Yang, H.C.; Wang, L.U.; Zhong, L.I.; Liu, Y.H.; Fan, R.X. Out of southern East Asia: The natural history of domestic dogs across the world. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanni, R.; Cafazzo, S.; Abis, A.; Barillari, E.; Valsecchi, P.; Natoli, E. Age-graded dominance hierarchies and social tolerance in packs of free-ranging dogs. Behav. Ecol. 2017, 28, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Behavior | Description | Type of Event |

|---|---|---|

| Inactive-neutral | ||

| Sitting | The dog is sitting with a stiff neck and straightened front legs | State event |

| Sleeping | Lying down with eyes closed | State event |

| Yawning | Long drawn breath | Point event |

| Active-positive | ||

| Following | Active proximity and unaggressive chase | State event |

| Licking | Pushing tongue against others to show dominance or affiliation | Point event |

| Playing | Tail up, direct stare, sitting or standing alert, pricked ears, barking | State event |

| Proximity | Switching the position, standing, seeking petting, raising a foreleg, gazing with the tail, sniffing | State event |

| Seeking petting | Nosing, rubbing, or pushing contact with the person | State event |

| Tail-wagging | The tail moves from side to side | State event |

| Stress-related | ||

| Attacking | Signs of aggression that may be accompanied by chasing | Point event |

| Barking | Strong sound coming out of the dog’s mouth | Point event |

| Dominance | Tail up, direct stare, sitting or standing alert, pricked ears, barking | State event |

| Fear | Tail dropping, lying on the back, flattened ears, lips retracted, high-pitched whine, high-pitched bark, backing away, licking lips, retreating, scanning | State event |

| Laying on the back | Posture taken during play, submission, or fear (depending on context) | State event |

| Model Variable | Description | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Response variable | ||

| Distance | Distance a dog followed the experimenter in each trial (1–3) | Continuous (0–600 m) |

| Explanatory variables | ||

| Age | Age class determined by the dog owner or the experimenter | Juvenile (6 months–2 years), adult (2–8 years), senior (>8 years) |

| Company | Other individuals present during the stimuli | Yes, no |

| Days | Days after the beginning of the first trial | 1–5 |

| ID | Individual dog | Continuous (1–129) |

| Location | Village where the experiment took place | Puerto Natales (PN), Porvenir (PV), Puerto Williams (PW) |

| Owner | Informed consent form signed by the dog owner | Yes, no |

| Sex | Sex determined by the dog owner or the experimenter | Male, female |

| Sociability (test) | Proportion of time of active-positive behaviors over the first 30 s | Continuous (proportion) |

| Sociability (overall) | Proportion of time of active-positive behaviors over all behaviors in the first 30 s | Continuous (proportion) |

| Stimulus | Stimulus the dog was exposed to | Voice, touch, food, control |

| Trial | Repetition of the stimulus during days 1–5 after the beginning of the first trial | Continuous (1–3) |

| Location | Voice | Touch | Food | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porvenir | 37.8 ± 61.8 | 0.8 ± 1.7 | 38.6 ± 58.8 | 26.1 ± 37.8 |

| Puerto Natales | 9.8 ± 13.2 | 24.5 ± 44.4 | 109 ± 175 | 25.6 ± 54.1 |

| Puerto Williams | 57.5 ± 170 | 23.6 ± 63.4 | 116 ± 141 | 44.8 ± 92.3 |

| Model | df | AIC | ΔAIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random effects | |||

| ~Stimulus*Days + Sex + Age + Company + Owner + Sociability (test) + (1|Location) + (1|Individual) g | 17 | 1649.3 | 0.0 |

| Fixed effects | |||

| ~Stimulus + Age + Company + Sociability (test) + (1|Location) + (1|Individual) * | 11 | 1640.3 | 0.0 |

| ~ Stimulus + Company + Sociability (test) + (1|Location) + (1|Individual) | 9 | 1641.1 | 0.76 |

| ~Stimulus + Sex + Age + Company + Sociability (test) + (1|Location) + (1|Individual) | 12 | 1641.2 | 0.86 |

| ~Stimulus + Sex + Company + Sociability (test) + (1|Location) + (1|Individual) | 10 | 1641.9 | 1.58 |

| ~Stimulus + Age + Days + Company + Sociability (test) + (1|Location) + (1|Individual) | 12 | 1641.9 | 1.62 |

| Company | Stimulus | Sociability (Test) | Age | Sex | Days | Owner | Days: Stimulus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of weights | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.41 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.03 |

| No. of models | 78 | 93 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 94 | 78 | 32 |

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.824 | 0.574 | |

| Stimulus–food a | 2.072 | 0.642 | <<0.001 |

| Stimulus–touch a | −0.528 | 0.565 | |

| Stimulus–voice a | 1.074 | 0.585 | |

| Company–ye s b | 1.897 | 0.421 | <<0.001 |

| Sociability (test) | 2.603 | 0.629 | <<0.001 |

| Age–senior c | −0.560 | 0.519 | 0.096 |

| Age–juvenile c | 0.859 | 0.546 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rojas-Troncoso, N.; Gómez-Silva, V.; Grimm-Seyfarth, A.; Schüttler, E. Dog–Stranger Interactions Can Facilitate Canine Incursion into Wilderness: The Role of Food Provisioning and Sociability. Biology 2025, 14, 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081006

Rojas-Troncoso N, Gómez-Silva V, Grimm-Seyfarth A, Schüttler E. Dog–Stranger Interactions Can Facilitate Canine Incursion into Wilderness: The Role of Food Provisioning and Sociability. Biology. 2025; 14(8):1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081006

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojas-Troncoso, Natalia, Valeria Gómez-Silva, Annegret Grimm-Seyfarth, and Elke Schüttler. 2025. "Dog–Stranger Interactions Can Facilitate Canine Incursion into Wilderness: The Role of Food Provisioning and Sociability" Biology 14, no. 8: 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081006

APA StyleRojas-Troncoso, N., Gómez-Silva, V., Grimm-Seyfarth, A., & Schüttler, E. (2025). Dog–Stranger Interactions Can Facilitate Canine Incursion into Wilderness: The Role of Food Provisioning and Sociability. Biology, 14(8), 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081006