Conservation of the Threatened Arabian Wolf (Canis lupus arabs) in a Mountainous Habitat in Northwestern Saudi Arabia

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

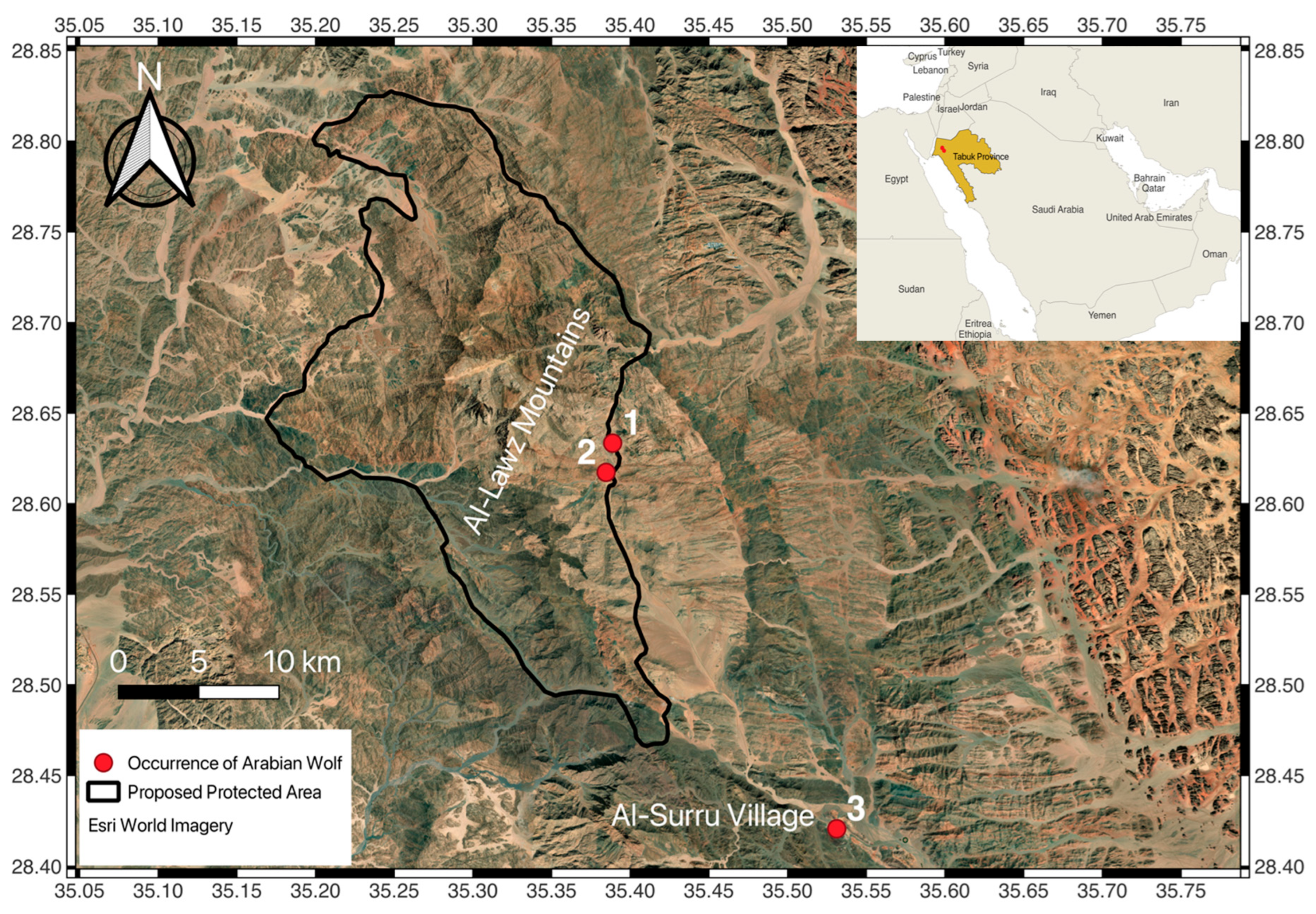

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Threats Facing the Arabian Wolf in the Study Area

4.1.1. Potential Hybridization Between Wolves and Free-Ranging Dogs

4.1.2. Human–Wolf Conflict

4.1.3. Human Expansion into Natural Habitats

4.2. Arabian Wolf Conservation Approaches

4.3. Arabian Wolf Distribution in the Study Area

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newbold, T.; Hudson, L.N.; Hill, S.L.; Contu, S.; Lysenko, I.; Senior, R.A.; Börger, L.; Bennett, D.J.; Choimes, A.; Collen, B.; et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 2015, 520, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ripple, W.J.; Newsome, T.M.; Wolf, C.; Dirzo, R.; Everatt, K.T.; Galetti, M.; Hayward, M.W.; Kerley, G.I.; Levi, T.; Lindsey, P.A.; et al. Collapse of the world’s largest herbivores. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1400103. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M.; Williams, D.R.; Kimmel, K.; Polasky, S.; Packer, C. Future threats to biodiversity and pathways to their prevention. Nature 2017, 546, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ripple, W.J.; Estes, J.A.; Beschta, R.L.; Wilmers, C.C.; Ritchie, E.G.; Hebblewhite, M.; Berger, J.; Elmhagen, B.; Letnic, M.; Nelson, M.P.; et al. Status and ecological effects of the world’s largest carnivores. Science 2014, 343, 1241484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Raven, P.H. Vertebrates on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13596–13602. [Google Scholar]

- Newbold, T.; Bentley, L.F.; Hill, S.L.; Edgar, M.J.; Horton, M.; Su, G.; Şekercioğlu, Ç.H.; Collen, B.; Purvis, A. Global effects of land use on biodiversity differ among functional groups. Funct. Ecol. 2020, 34, 684–693. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Fernández, M.; Harcourt, R.; Newsome, T.; Towerton, A.; Carthey, A. Adaptations of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) to urban environments in Sydney, Australia. J. Urban Ecol. 2020, 6, juaa009. [Google Scholar]

- Alatawi, A.S. Role of Agricultural Areas as Shelters for Carnivores in a Desert Ecosystem in Saudi Arabia. Pak. J. Zool. 2024, 56, 2227–2234. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, C.; Ripple, W.J. Prey depletion as a threat to the world’s large carnivores. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 160252. [Google Scholar]

- Contesse, P.; Hegglin, D.; Gloor, S.; Bontadina, F.; Deplazes, P. The diet of urban foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and the availability of anthropogenic food in the city of Zurich, Switzerland. Mamm. Biol. 2004, 69, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, P.W.; Fleming, P.A. Big city life: Carnivores in urban environments. J. Zool. 2012, 287, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Handler, A.M.; Lonsdorf, E.V.; Ardia, D.R. Evidence for red fox (Vulpes vulpes) exploitation of anthropogenic food sources along an urbanization gradient using stable isotope analysis. Can. J. Zool. 2020, 98, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Plumer, L.; Davison, J.; Saarma, U. Rapid Urbanization of Red Foxes in Estonia: Distribution, Behaviour, Attacks on Domestic Animals, and Health-Risks Related to Zoonotic Diseases. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115124. [Google Scholar]

- Soulsbury, C.D.; White, P.C. Human–wildlife interactions in urban areas: A review of conflicts, benefits and opportunities. Wildl. Res. 2015, 42, 541–553. [Google Scholar]

- Schell, C.J.; Stanton, L.A.; Young, J.K.; Angeloni, L.M.; Lambert, J.E.; Breck, S.W.; Murray, M.H. The evolutionary consequences of human–wildlife conflict in cities. Evol. Appl. 2021, 14, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alatawi, A.S. Conservation action in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and opportunities. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 3466–3472. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, A.; Mahmood, T.; Fatima, H.; Hennelly, L.M.; Akrim, F.; Hussain, A.; Waseem, M. Origin, ecology and human conflict of gray wolf (Canis lupus) in Suleman Range, South Waziristan, Pakistan. Mammalia 2019, 83, 539–551. [Google Scholar]

- Al Ahmari, A.; Neyaz, F.; Shuraim, F.; Al Ghamdi, A.; Al Boug, A.; Alhlafi, M.; Al Jbour, S.; Angelici, F.M.; Alaamri, S.; Al Masabi, K.; et al. Diversity and Conservation of Carnivores in Saudi Arabia. Diversity 2025, 17, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, T.M.; Boitani, L.; Chapron, G.; Ciucci, P.; Dickman, C.R.; Dellinger, J.A.; López-Bao, J.V.; Peterson, R.O.; Shores, C.R.; Wirsing, A.J.; et al. Food habits of the world’s grey wolves. Mammal Rev. 2016, 46, 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Ma, Y.-P.; Zhou, Q.-J.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Savolainen, P.; Wang, G.-D. The geographical distribution of grey wolves (Canis lupus) in China: A systematic review. Zool. Res. 2016, 37, 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Boitani, L.; Phillips, M.; Jhala, Y. Canis lupus (Amended Version of 2018 Assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023: E.T3746A247624660. 2023. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/3746/247624660 (accessed on 5 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bonsen, G.T.; Wallach, A.D.; Ben-Ami, D.; Keynan, O.; Khalilieh, A.; Dahdal, Y.; Ramp, D. Navigating complex geopolitical landscapes: Challenges in conserving the endangered Arabian wolf. Biol. Conserv. 2024, 296, 110655. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, O.; Barocas, A.; Geffen, E. Conflicting management policies for the Arabian wolf Canis lupus arabs in the Negev Desert: Is this justified? Oryx 2013, 47, 228–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ripple, W.J.; Beschta, R.L. Trophic cascades in Yellowstone: The first 15 years after wolf reintroduction. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 145, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve, K.A.; Proulx, G. Ecological advantages of grey wolf (Canis lupus) reintroductions and recolonizations in North America. In Wildlife Conservation and Management in the 21st Century-Issues, Solutions, and New Concepts; Proulx, G., Ed.; Alpha Wildlife Publications: Sherwood Park, AB, Canada, 2024; pp. 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Zlatanova, D.; Ahmed, A.; Valasseva, A.; Genov, P. Adaptive diet strategy of the wolf (Canis lupus L.) in Europe: A review. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2014, 66, 439–452. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, A.; Kaboli, M.; Sazatornil, V.; Lopez-Bao, J.V. Anthropogenic food resources sustain wolves in conflict scenarios of Western Iran. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218345. [Google Scholar]

- Mallon, D.P.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Amori, G.; Baldwin, R.; Bradshaw, P.L.; Budd, K. The Conservation Status and Distribution of the Mammals of the Arabian Peninsula; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Environment and Protected Areas Authority: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2023.

- Bray, T.C.; Mohammed, O.B.; Butynski, T.M.; Wronski, T.; Sandouka, M.A.; Alagaili, A.N. Genetic variation and subspecific status of the grey wolf (Canis lupus) in Saudi Arabia. Mamm. Biol. 2014, 79, 409–413. [Google Scholar]

- Eid, E.; Abu Baker, M.; Amr, Z. National Red Data Book of Mammals in Jordan; IUCN Regional Office for West Asia Amman: Amman, Jordan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsen, G.T.; Wallach, A.D.; Ben-Ami, D.; Keynan, O.; Khalilieh, A.; Shanas, U.; Wooster, E.I.; Ramp, D. Tolerance of wolves shapes desert canid communities in the Middle East. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 36, e02139. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, P.L.; Wronski, T. Arabian Wolf Distribution Update from Saudi Arabia. Canid News 2010, 13. Available online: http://www.canids.org/canidnews/13/Arabian_wolf_in_Saudi_Arabia.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Wronski, T.; Macasero, W. Evidence for the persistence of Arabian Wolf (Canis lupus pallipes) in the Ibex Reserve, Saudi Arabia and its preferred prey species. Zool. Middle East 2008, 45, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Aloufi, A.A.; Amr, Z.S. Carnivores of the Tabuk Province, Saudi Arabia (Carnivora: Canidae, Felidae, Hyaenidae, Mustelidae). Lynx New Ser. 2018, 49, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar-ul Islam, M.; Boug, A.; Shehri, A.; da Silva, L.G. Geographic distribution patterns of melanistic Arabian Wolves, Canis lupus arabs (Pocock), in Saudi Arabia (Mammalia: Carnivora). Zool. Middle East 2019, 65, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Aloufi, A.; Eid, E. Conservation perspectives of illegal animal trade at markets in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. TRAFFIC Bull. 2014, 26, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Al Saud, M.M. Sustainable Land Management for NEOM Region; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Randi, E. Genetics and conservation of wolves Canis lupus in Europe. Mammal Rev. 2011, 41, 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lescureux, N.; Linnell, J.D. Warring brothers: The complex interactions between wolves (Canis lupus) and dogs (Canis familiaris) in a conservation context. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 171, 232–245. [Google Scholar]

- Donfrancesco, V.; Ciucci, P.; Salvatori, V.; Benson, D.; Andersen, L.W.; Bassi, E.; Blanco, J.C.; Boitani, L.; Caniglia, R.; Canu, A.; et al. Unravelling the Scientific Debate on How to Address Wolf-Dog Hybridization in Europe. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 175. [Google Scholar]

- Randi, E. Detecting hybridization between wild species and their domesticated relatives. Mol. Ecol. 2008, 17, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Werhahn, G.; Senn, H.; Macdonald, D.W.; Sillero-Zubiri, C. The Diversity in the Genus Canis Challenges Conservation Biology: A Review of Available Data on Asian Wolves. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 782528. [Google Scholar]

- Werhahn, G.; Augugliaro, C.; Kabir, M.; Hennelly, L.M.; Chetri, M.; Al Hikmani, H.; Mohammadi, A.; Jhala, Y.V.; Macdonald, D.W.; Farhadinia, M.S. Asia’s Wolves and Synergies with Big Cats. Conserv. Lett. 2025, 18, e13094. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, S. Return of grey wolf (Canis lupus) to Central Europe: Challenges and recommendations for future management in cultural landscapes. Ann. For. Res. 2018, 61, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Barichievy, C.; Clugston, S.; Sheldon, R. Association between an Arabian wolf and a domestic dog in central Saudi Arabia. Canid Biol. Conserv. 2017, 20, 25–27. Available online: http://canids.org/CBC/20/Arabian_wolf_and_domestic_dog_in_saudi_arabia.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Mallon, D.; Budd, K. (Eds.) Regional Red List Status of Carnivores in the Arabian Peninsula; IUCN: Cambridge, UK; Gland, Switzerland; Environment and Protected Areas Authority: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2011; p. vi+49.

- König, H.J.; Ceaușu, S.; Reed, M.; Kendall, H.; Hemminger, K.; Reinke, H.; Ostermann Miyashita, E.F.; Wenz, E.; Eufemia, L.; Hermanns, T.; et al. Integrated framework for stakeholder participation: Methods and tools for identifying and addressing human–wildlife conflicts. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e399. [Google Scholar]

- Basak, S.M.; Rostovskaya, E.; Birks, J.; Wierzbowska, I.A. Perceptions and attitudes to understand human-wildlife conflict in an urban landscape—A systematic review. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151, 110319. [Google Scholar]

- Lazure, L.; Weladji, R.B. Methods to mitigate human–wildlife conflicts involving common mesopredators: A meta-analysis. J. Wildl. Manag. 2024, 88, e22526. [Google Scholar]

- Janeiro-Otero, A.; Newsome, T.M.; Van Eeden, L.M.; Ripple, W.J.; Dormann, C.F. Grey wolf (Canis lupus) predation on livestock in relation to prey availability. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 243, 108433. [Google Scholar]

- Montanheiro Paolino, R.; Testa Jose, C.; Fernandes-Santos, R.C.; Bueno Landis, M.; Medeiros de Pinho, G.; Medici, E.P. Poaching and hunting, conflicts and health: Human dimensions of wildlife conservation in the Brazilian Cerrado. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2024, 4, 1221206. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P.J.; Dowding, C.V.; Molony, S.E.; White, P.C.; Harris, S. Activity patterns of urban red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) reduce the risk of traffic-induced mortality. Behav. Ecol. 2007, 18, 716–724. [Google Scholar]

- Kobryn, H.T.; Swinhoe, E.J.; Bateman, P.W.; Adams, P.J.; Shephard, J.M.; Fleming, P.A. Foxes at your front door? Habitat selection and home range estimation of suburban red foxes (Vulpes vulpes). Urban Ecosyst. 2023, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Barichievy, C.; Sheldon, R.; Wacher, T.; Llewellyn, O.; Al-Mutairy, M.; Alagaili, A. Conservation in Saudi Arabia; moving from strategy to practice. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 290–292. [Google Scholar]

- Seddon, P.J.; van Heezik, H.; Nader, I.A. Mammals of the Harrat al-Harrah Protected Area, Saudi Arabia. Zool. Middle East 1997, 14, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP-WCMC. Protected Area Profile for Jabal al-Lawz from the World Database on Protected Areas, March 2025. Available online: www.protectedplanet.net (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Marker, L.L.; Dickman, A.J.; Macdonald, D.W. Perceived effectiveness of livestock-guarding dogs placed on Namibian farms. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 58, 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Xie, L.; Huang, S.L.; Li, P.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, W. Using social media to strengthen public awareness of wildlife conservation. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 153, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, R.; Tsunoda, H.; Enari, H.; Siemer, W.F.; Uehara, T.; Stedman, R.C. Factors affecting attitudes toward reintroduction of wolves in Japan. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e01036. [Google Scholar]

- Barmoen, M.; Bærum, K.M.; Mathiesen, K.E. Living with wolves: A worldwide systematic review of attitudes. Ambio 2024, 53, 1414–1432. [Google Scholar]

- Theuerkauf, J. What Drives Wolves: Fear or Hunger? Humans, Diet, Climate and Wolf Activity Patterns. Ethology 2009, 115, 649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Llaneza, L.; López-Bao, J.V.; Sazatornil, V. Insights into wolf presence in human-dominated landscapes: The relative role of food availability, humans and landscape attributes. Divers. Distrib. 2012, 18, 459–469. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, I.; Krofel, M.; Mota, P.G.; Álvares, F. Consumption of carnivores by wolves: A worldwide analysis of patterns and drivers. Diversity 2020, 12, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.T.; Silva, N.; Brotas, G.; Fonseca, C. To Eat or Not to Eat? The Diet of the Endangered Iberian Wolf (Canis lupus signatus) in a Human-Dominated Landscape in Central Portugal. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129379. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture. Executive Regulations for Hunting Wildlife. Available online: https://www.mewa.gov.sa/ar/InformationCenter/DocsCenter/RulesLibrary/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 22 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alatawi, A.S. Conservation of the Threatened Arabian Wolf (Canis lupus arabs) in a Mountainous Habitat in Northwestern Saudi Arabia. Biology 2025, 14, 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14070839

Alatawi AS. Conservation of the Threatened Arabian Wolf (Canis lupus arabs) in a Mountainous Habitat in Northwestern Saudi Arabia. Biology. 2025; 14(7):839. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14070839

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlatawi, Abdulaziz S. 2025. "Conservation of the Threatened Arabian Wolf (Canis lupus arabs) in a Mountainous Habitat in Northwestern Saudi Arabia" Biology 14, no. 7: 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14070839

APA StyleAlatawi, A. S. (2025). Conservation of the Threatened Arabian Wolf (Canis lupus arabs) in a Mountainous Habitat in Northwestern Saudi Arabia. Biology, 14(7), 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14070839