1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer remains the most lethal gynecological malignancy, with the majority of patients being diagnosed at advanced stages of the disease [

1]. Standard treatment typically involves optimal surgical cytoreduction followed by platinum and taxane based chemotherapy. Although initial response rates are promising, a substantial proportion of patients eventually experience relapse, which is frequently accompanied by the development of multidrug resistance (MDR). MDR significantly reduces chemotherapeutic efficacy and represents a major challenge in ovarian cancer management [

2,

3]. Consequently, the identification of novel therapeutic strategies capable of enhancing the effectiveness of existing agents and overcoming resistance mechanisms is urgently needed.

Doxorubicin (Adriamycin), an anthracycline antibiotic, exerts potent anticancer activity by intercalating into DNA and inhibiting topoisomerase II, leading to impaired DNA replication and apoptosis [

4]. Despite its broad-spectrum antitumor effects, its clinical utility is restricted by significant dose limiting toxicities most notably cardiotoxicity as well as the emergence of tumor resistance [

5]. These challenges underscore the importance of exploring combinatorial approaches that can enhance adriamycin efficacy while reducing toxicity, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes.

Metformin, a biguanide commonly prescribed as a first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes, has garnered increasing attention in oncology. Epidemiological studies indicate that metformin use in diabetic patients is associated with reduced cancer incidence and mortality [

6,

7]. Although its anticancer mechanisms are not fully clarified, metformin is known to exert multiple effects, including activation of AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK), inhibition of the mTOR signaling pathway, induction of cell cycle arrest, and modulation of apoptotic and oxidative stress responses [

8,

9]. These pleiotropic actions suggest that metformin may enhance the efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutics when used in combination.

Apoptosis is a key programmed cell death mechanism underlying the antitumor activity of many chemotherapeutic agents. It involves the activation of both extrinsic (caspase-8) and intrinsic mitochondrial (caspase-9) pathways and is tightly regulated by anti- and pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2, Bax, and Survivin [

10]. Dysregulation of these pathways contributes to chemoresistance in many cancers. Emerging evidence indicates that metformin can potentiate the apoptotic effects of chemotherapeutics by modulating these pathways and weakening anti-apoptotic defenses [

11].

Given this background, the present study aimed to comprehensively evaluate the individual and combined effects of metformin and adriamycin in OVCAR3 and SKOV3 ovarian cancer cell lines, both of which represent aggressive and treatment-resistant disease phenotypes. Beyond assessing antiproliferative and apoptotic responses, we investigated several mechanistic endpoints, including caspase-8 and caspase-9 activation, expression of apoptosis related genes (Bcl-2, Survivin, Bax, and Caspase-3), oxidative and nitrosative stress parameters, and bioinformatic analyses using TCGA and STRING databases. This integrated approach is expected to provide detailed mechanistic insight into how metformin enhances adriamycin efficacy and may contribute to the development of more effective combination strategies for overcoming chemoresistance in ovarian cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

Human ovarian cancer cell lines OVCAR3 and SKOV3 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). OVCAR3 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Billings, MT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco), and 1% sodium pyruvate. SKOV3 cells were maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium (Gibco) containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. All cell lines were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 using a standard cell culture incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Cells were subcultured at 70–80% confluence and used for experiments between passages 5 and 20 to ensure phenotypic stability. Mycoplasma contamination was routinely assessed using a commercial detection kit, and all cultures tested negative. Media selection for each cell line followed ATCC recommendations: RPMI-1640 for OVCAR3 and McCoy’s 5A for SKOV3.

2.2. Drugs and Solutions

Metformin hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and adriamycin hydrochloride (Adriamycin; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were prepared as master stock solutions according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Metformin was dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to obtain a 1 M stock solution and stored at −20 °C. Adriamycin was prepared as a 2 mM stock solution in sterile distilled water, aliquoted to avoid repeated freeze–thaw cycles, and stored at −20 °C protected from light due to its photosensitivity.

Before each experiment, the required working concentrations were freshly prepared by diluting the stock solutions with the corresponding complete culture media. All solutions were filtered through 0.22 μm sterile syringe filters to ensure sterility prior to use.

2.3. Cell Viability and Proliferation Assay (MTT Assay)

Cell viability was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. OVCAR3 and SKOV3 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well and allowed to adhere for 24 h. Cells were then treated with increasing concentrations of metformin (0, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 mM), adriamycin (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 µM), or their combinations for 24 and 48 h.

For combination and synergy analyses, metformin and adriamycin were applied concurrently at a fixed ratio determined from their respective IC

50 values. For synergy analyses, metformin and Adriamycin were combined at fixed IC

50-based ratios (0.25×, 0.5×, 1×, 2×, and 4×), derived from the dose–response curves in

Figure 1. A serial dilution of 0.25×, 0.5×, 1×, 2×, and 4× the IC

50 concentration of each drug was used. Fraction affected (Fa) values, representing the proportion of non-viable cells, were calculated and ranged between 0.2 and 0.8 for subsequent Chou–Talalay synergy modeling.

Following drug exposure, 20 µL of MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. The resulting formazan crystals were dissolved by adding 100 µL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich), and absorbance was measured at 570 nm with a reference wavelength of 630 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Background readings from blank wells were subtracted before analysis.

All experiments were performed in at least three independent replicates (n = 3). Cell viability was normalized to untreated control wells (set to 100%), which included DMSO vehicle controls. IC50 values were calculated using nonlinear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA).

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 serve two distinct analytical purposes.

Figure 1 presents the individual dose–response curves of metformin and adriamycin across broad concentration ranges to determine IC

50 values using nonlinear regression modeling. In contrast,

Figure 2 focuses exclusively on fixed IC

50-based combination treatments used for synergy analyses. Therefore, the concentration intervals differ between the two figures because

Figure 1 displays exploratory dose–response profiling, whereas

Figure 2 visualizes outcomes under standardized fixed-ratio combination doses designed for Chou–Talalay and HSA synergy modeling. The concentration increments in

Figure 1 intentionally differ from those in

Figure 2, as IC

50 determination requires a wide nonlinear concentration range, while synergy analysis requires narrow IC

50-based dilutions.

2.4. Apoptosis Detection (Flow Cytometry)

Apoptosis was quantified using the Annexin V-FITC/Propidium Iodide (PI) Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. OVCAR3 and SKOV3 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were then treated with the IC50 concentrations of metformin, adriamycin, or their combination for 48 h.

Following treatment, both adherent and floating cells were collected to avoid loss of apoptotic and necrotic populations. Cells were harvested by trypsinization using enzyme-free dissociation buffer, centrifuged, and washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Pellets were resuspended in 1× binding buffer provided with the kit. Subsequently, 5 µL Annexin V-FITC and 5 µL PI were added to 100 µL of cell suspension and incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. After staining, 400 µL of binding buffer was added, and samples were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

Data acquisition was performed using a BD FACS Celesta flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA), and compensation settings were applied using single-stained controls. A minimum of 10,000 events per sample was collected after excluding doublets via FSC-A versus FSC-H gating. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 10.8.1, Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

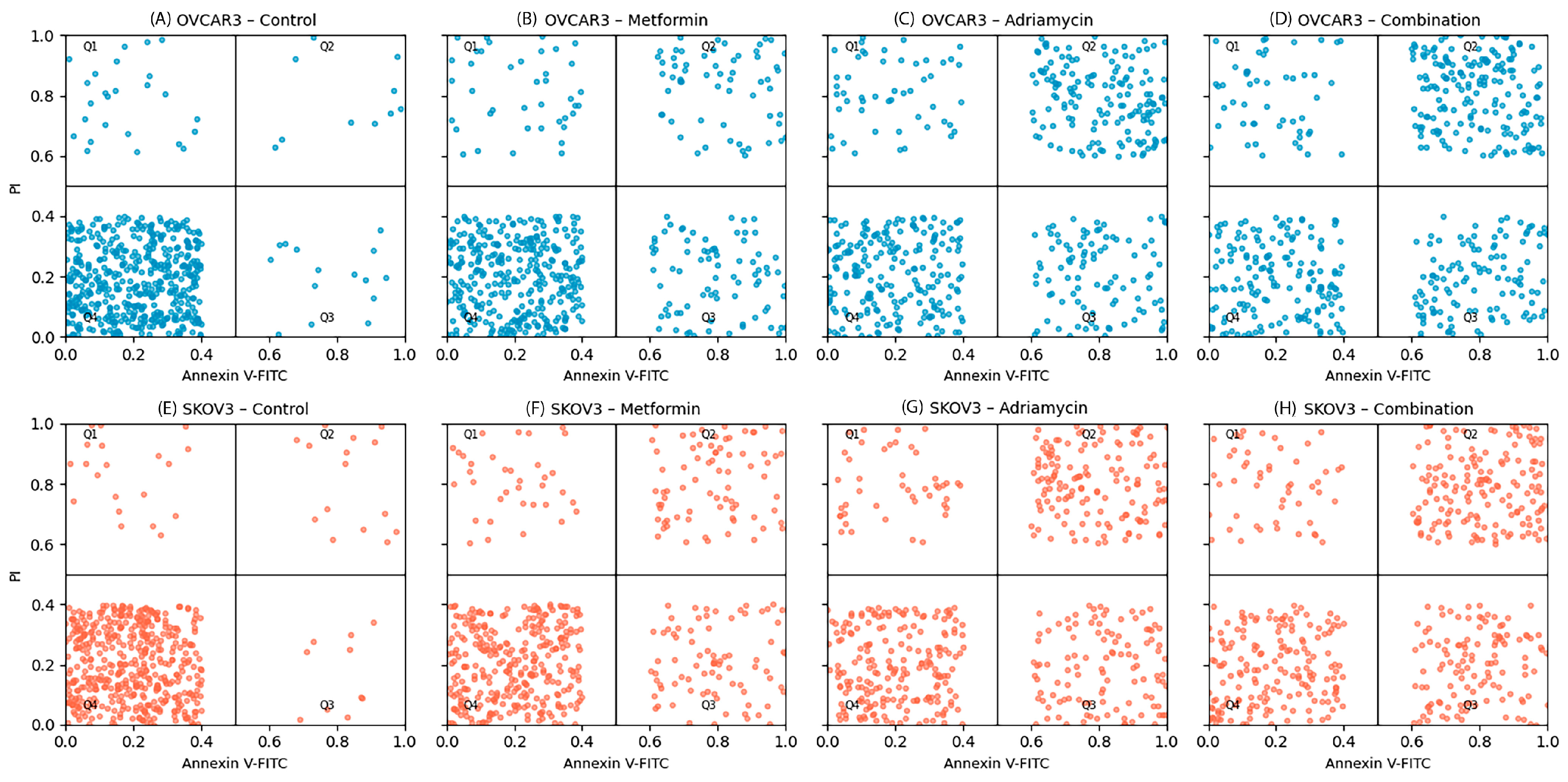

Quadrant gating was established according to unstained and drug-free control cells. The quadrants were defined as follows:

Q1 (PI+/Annexin V−): Necrotic cells;

Q2 (PI+/Annexin V+): Late apoptotic/secondary necrotic cells;

Q3 (PI−/Annexin V+): Early apoptotic cells;

Q4 (PI−/Annexin V−): Viable cells.

Apoptotic indices were calculated as the sum of early (Q3) and late (Q2) apoptotic populations.

2.5. Caspase 8 and Caspase 9 Activity Assays

Caspase-8 and caspase-9 enzymatic activities were measured using colorimetric assay kits (BioVision, Milpitas, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following drug treatments, cells were harvested and lysed using the lysis buffer provided in the kits. Lysates were incubated on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 12,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove cellular debris. Protein concentrations were quantified using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Equal amounts of total protein (50–100 µg per reaction) were transferred to 96-well plates and incubated with 2× reaction buffer containing 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and the specific chromogenic substrates IETD-pNA (for caspase-8) or LEHD-pNA (for caspase-9). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 2–4 h in the dark. Hydrolysis of the substrates released p-nitroaniline (pNA), which was quantified by measuring absorbance at 405 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, USA). Background absorbance from blank wells was subtracted from all readings. Caspase activities were normalized to protein content and expressed as fold changes relative to untreated control samples.

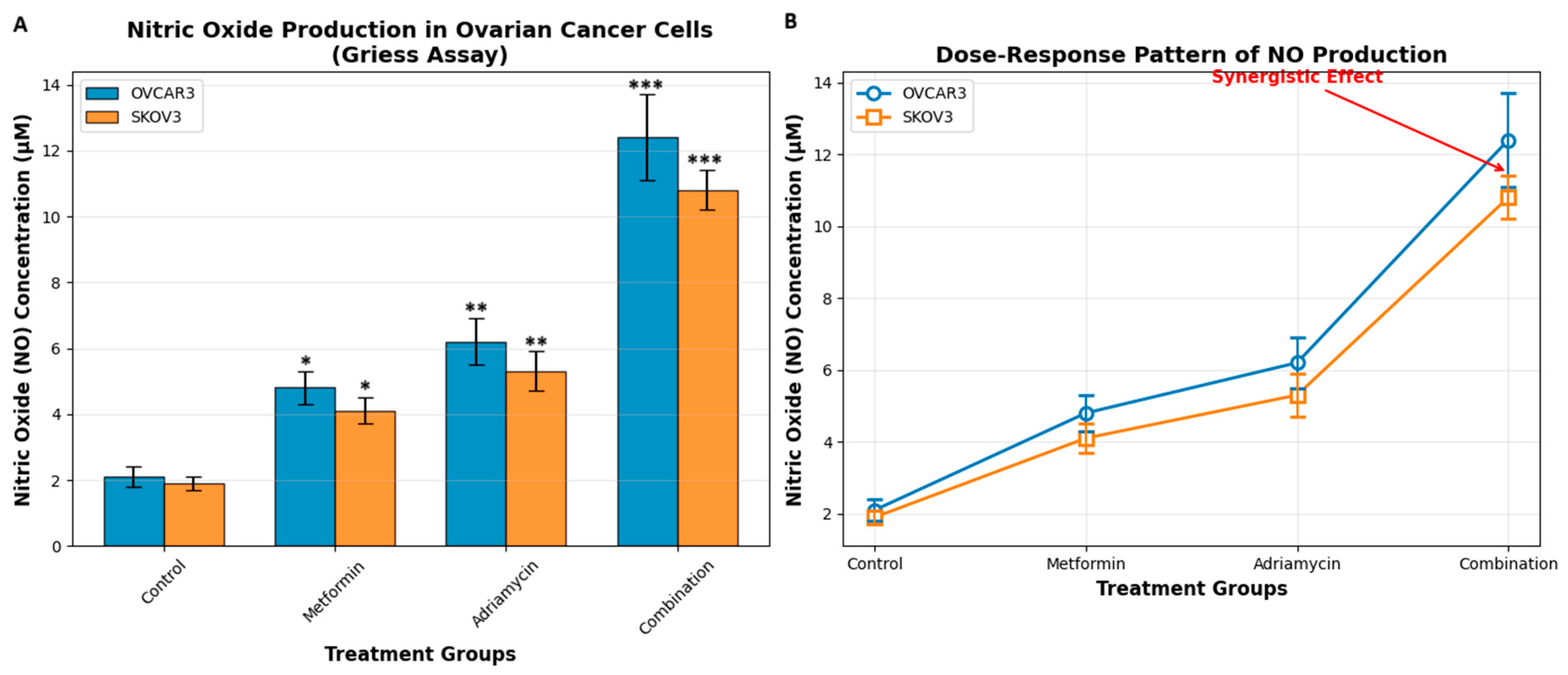

2.6. Nitric Oxide Analysis

NO production was quantified indirectly by measuring nitrite (NO2−), a stable oxidation product of NO, using the Griess reagent system (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). After drug treatments (48 h IC50 Adriamycin and Metformin), culture supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 12,000× g for 5 min to remove debris. Equal volumes of cell culture supernatant (100 µL) and Griess reagent (100 µL) were mixed in 96-well plates and incubated at room temperature for 15 min in the dark.

The absorbance of the resulting azo dye was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, USA). Nitrite concentrations were calculated from a freshly prepared sodium nitrite (NaNO2) standard curve ranging from 0 to 100 µM. Blank wells containing medium only were used to subtract background absorbance.

To account for differences in cell number, nitrite levels were normalized to total protein content from corresponding wells, quantified using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, USA). All measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.7. Oxidative Stress Measurement (Reactive Oxygen Species—ROS Detection)

Intracellular ROS levels were measured using the 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) probe (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). OVCAR3 and SKOV3 cells were seeded into black 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well and treated with the IC50 concentrations of metformin, adriamycin, and their combination for 48 h.

Following treatment, cells were washed twice with warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove phenol red and serum components that could interfere with fluorescence. Cells were then incubated with 10 µM DCFH-DA prepared in serum-free medium for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark to allow intracellular deacetylation to DCFH. After incubation, excess probe was removed by washing cells twice with PBS. Fluorescence intensity was measured immediately using a fluorescence microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 535 nm. Background fluorescence was corrected using cell-free wells containing DCFH-DA.

To normalize ROS production to cell number, total protein content from parallel wells was quantified using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, USA). ROS levels were reported as relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) per µg protein. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

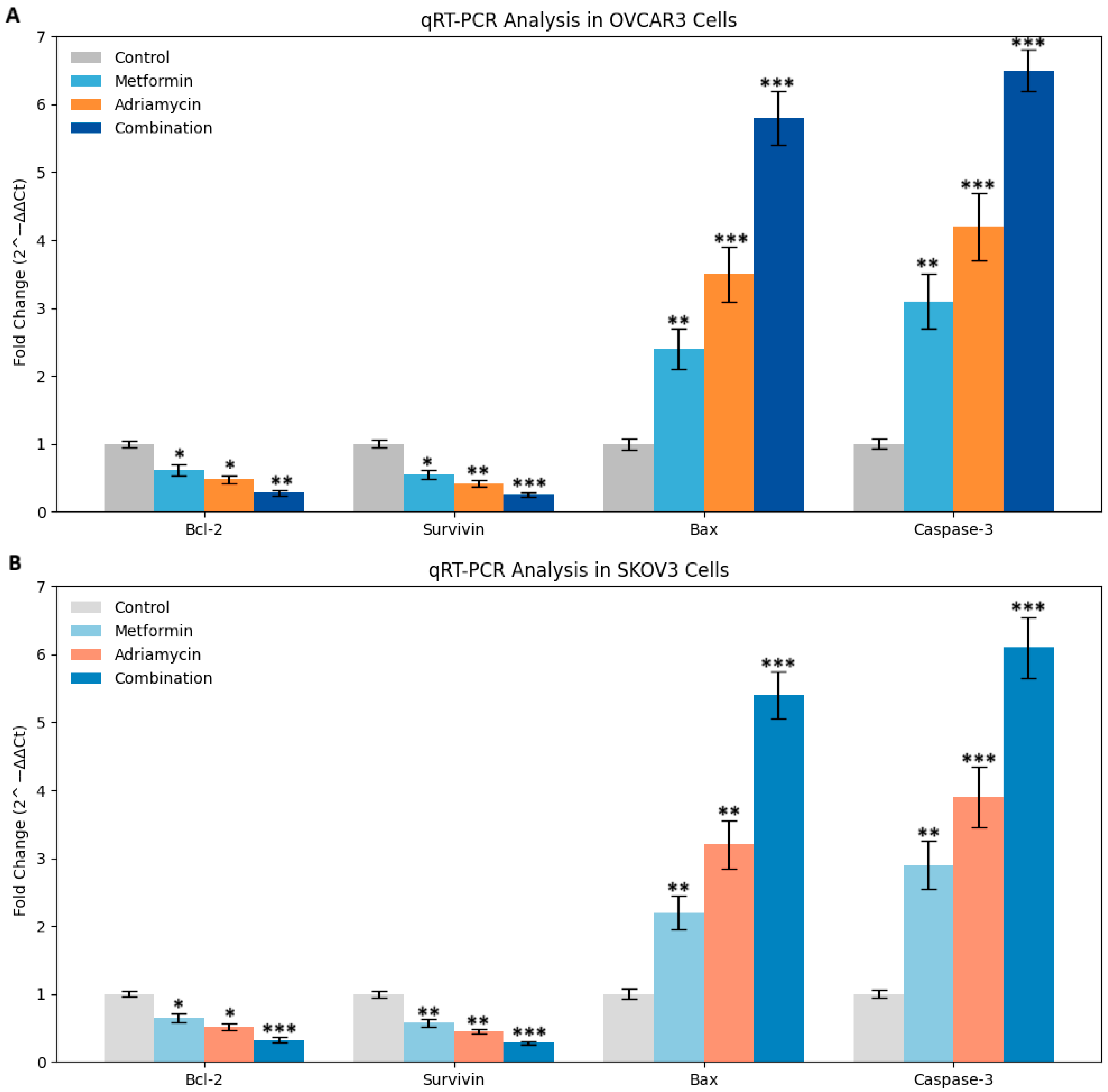

2.8. Gene Expression Analysis by Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from treated and control OVCAR3 and SKOV3 cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA purity and concentration were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and samples with A260/280 ratios between 1.8 and 2.1 were used for further analysis. Genomic DNA contamination was removed by DNase I treatment (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). RNA integrity was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis.

For cDNA synthesis, 1 µg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) with oligo(dT) primers in a 20 µL reaction volume, following the manufacturer’s protocol. qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA) on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System. Gene-specific primers were designed to span exon–exon junctions and were validated for specificity and efficiency (90–110%). Melt curve analysis was performed for each reaction to confirm single amplicon formation.

The expression levels of Bcl-2, Survivin, Bax, and Caspase-3 were quantified, while GAPDH and β-actin served as reference genes, which showed stable Ct values under all treatment conditions. The sequences of primers used in this study are listed in

Table 1. Each reaction was carried out in triplicate with a final reaction volume of 20 µL, including no-template controls (NTC) and no-reverse-transcriptase controls (no-RT) to exclude contamination.

For normalization, GAPDH was used as the primary reference gene, and ACTB was included as a secondary internal control to verify reference gene stability. All fold-change calculations were ultimately derived using GAPDH-normalized ΔCt values, as GAPDH exhibited the lowest Ct variation among treatment groups.

Thermal cycling conditions included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 amplification cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with Ct values above 35 excluded from analysis.

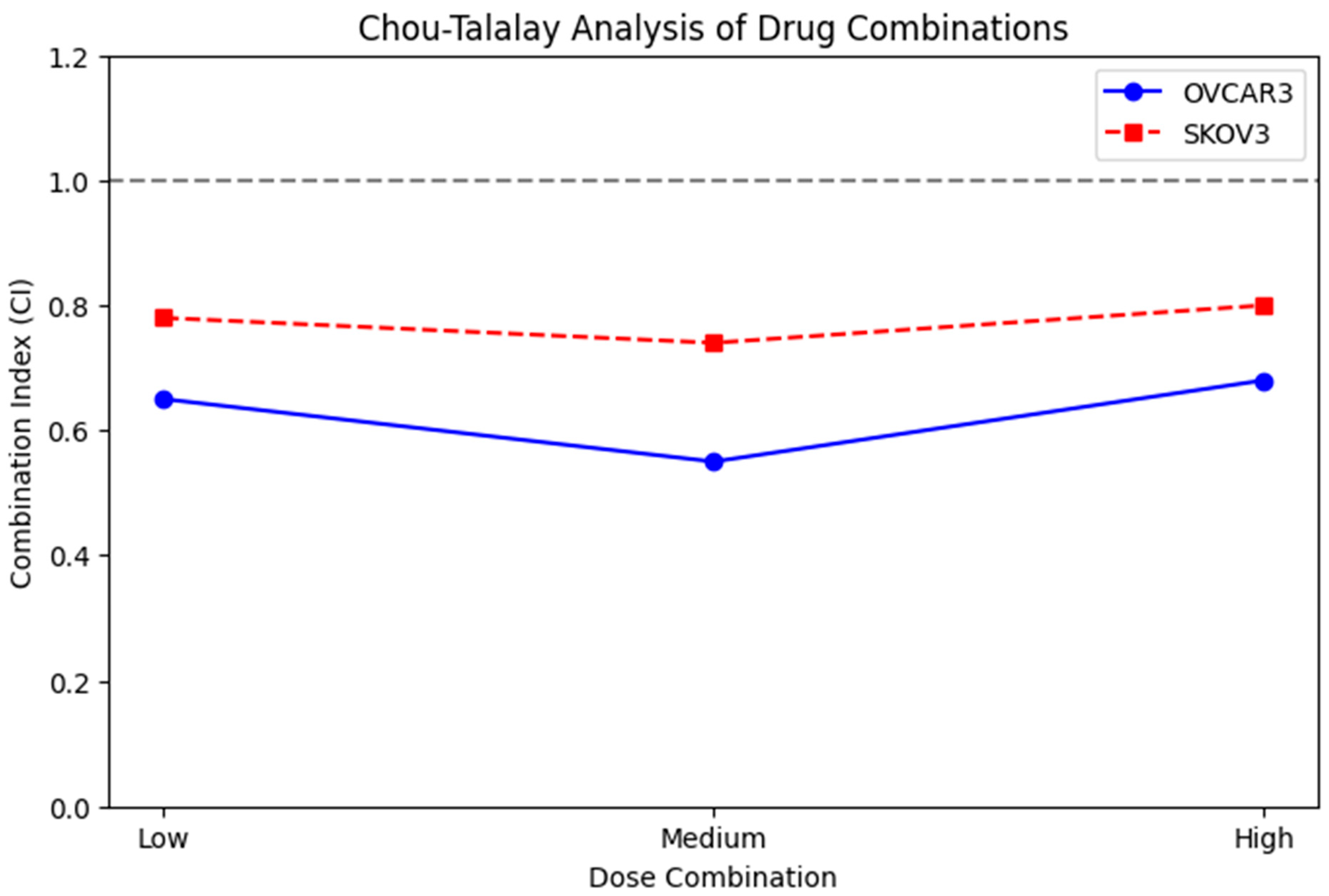

2.9. Synergy Analysis of Drug Combinations

Drug interaction analysis between metformin and adriamycin was performed using the Chou–Talalay CI method. Dose–response curves and fraction affected (Fa) values were generated from MTT viability data obtained at multiple fixed-ratio drug concentrations. Fixed ratios were established based on the IC50 values of each drug, and serial dilutions ranging from 0.25× to 4× IC50 were applied to generate Fa values be-tween 0.2 and 0.8. After determining the 24 and 48 h IC50 values for metformin and adriamycin, drug combinations were prepared according to the fixed ratio principle of 1:1, 1:2, and 2:1 based on IC50 (Met):IC50 (DOX) ratios. Each of these mixtures was seri-ally diluted to create five different combination doses. These data were then used to calculate the CI using the Chou–Talalay CI method.

CI values were calculated using CompuSyn software (version 1.0, ComboSyn Inc., Paramus, NJ, USA), which applies the median-effect principle to determine the nature of the drug interaction. A CI < 1 indicates synergism, CI = 1 indicates an additive effect, and CI > 1 indicates antagonism. Dose-reduction index (DRI) values and isobologram plots were also generated to further characterize drug interactions. CI values were reported at multiple effect levels (Fa50, Fa75, Fa90) to provide a comprehensive synergy profile.

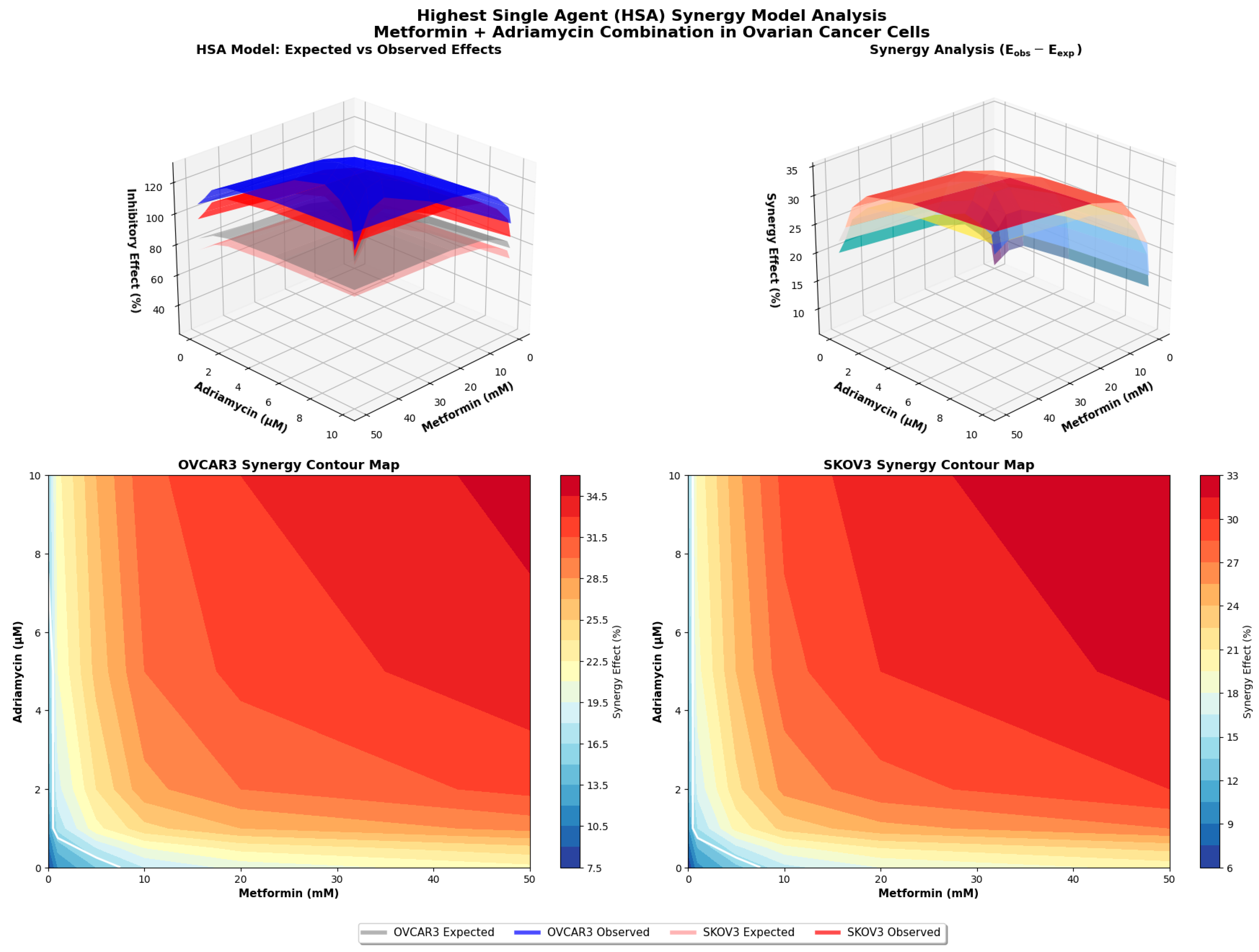

2.10. Highest Single-Agent Synergism Model Analysis

HSA model was used as an independent approach to validate the synergistic interaction between metformin and adriamycin. In this model, the effect of a drug combination is compared directly with the highest effect produced by either drug alone at the corresponding concentrations.

For each concentration pair, the expected effect (E

exp) was calculated using the standard HSA formula:

where E

A and E

B represent the fractional inhibitory effects of metformin and adriamycin, respectively, normalized to untreated controls. The experimentally observed combination effect (E

obs) was derived from MTT viability assays and expressed as fractional inhibition.

Synergy was defined when Eobs > Eexp with statistical significance (p < 0.05). All analyses were performed using triplicate biological replicates, and statistical comparisons between Eobs and Eexp were made using paired t-tests in GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, USA). Results were visualized in 3D response surface plots to illustrate the interaction landscape across all dose combinations.

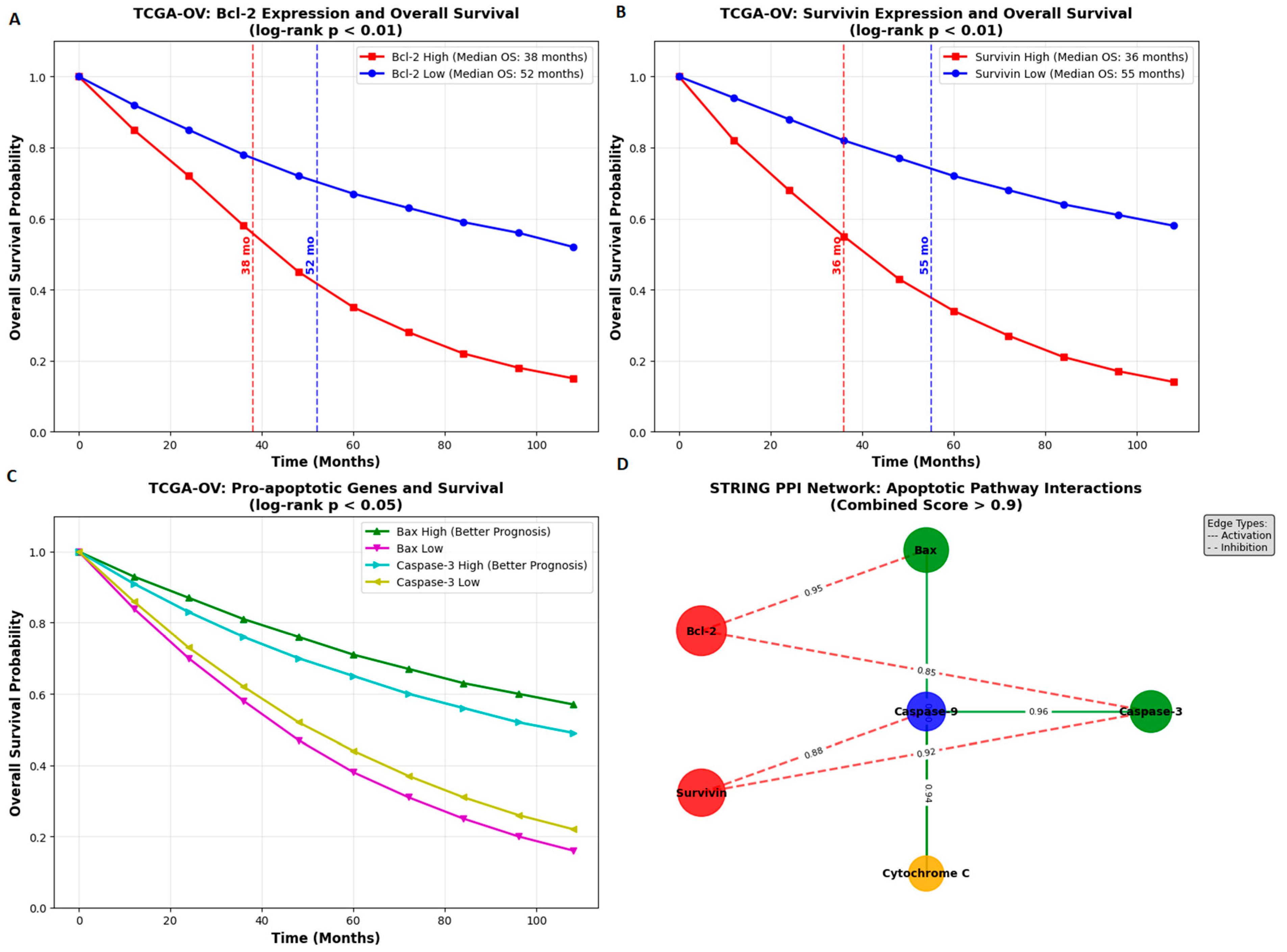

2.11. Bioinformatics Analysis

Bioinformatic analyses were conducted to evaluate the prognostic significance and interaction networks of apoptosis-related genes, including Bcl-2, Survivin (BIRC5), Bax, and Caspase-3. Transcriptomic and clinical data for ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA-OV cohort) were retrieved from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (accessed on 10 November 2025). Gene expression values were normalized as transcripts per million (TPM) using the GEPIA2 web platform (

http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn; accessed on 10 November 2025).

Overall survival (OS) analyses were performed using Kaplan–Meier plots generated in GEPIA2, with patients stratified based on median expression cutoffs. Statistical significance was assessed using the log-rank test (p < 0.05), and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals were recorded.

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks were analyzed using the STRING database (

https://string-db.org; accessed on 10 November 2025). A minimum interaction confidence score of 0.700 (high confidence) was applied. Interactions supported by experimental evidence, curated databases, co-expression, and sequence homology were included. Functional enrichment analyses for Gene Ontology (GO) terms and KEGG pathways were performed, with statistical significance determined using false discovery rate (FDR) correction (FDR < 0.05).

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed with at least three independent biological replicates (n ≥ 3). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, USA). The normality of data distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances was confirmed using Levene’s test.

Comparisons among multiple groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons. For comparisons between two groups, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used. In synergy assessments, comparisons between expected (Eexp) and observed (Eobs) effects in the HSA model were evaluated using paired t-tests. Survival analyses based on GEPIA2 data were assessed using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test, and hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals were reported.

A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical assumptions were checked before conducting parametric tests.

4. Discussion

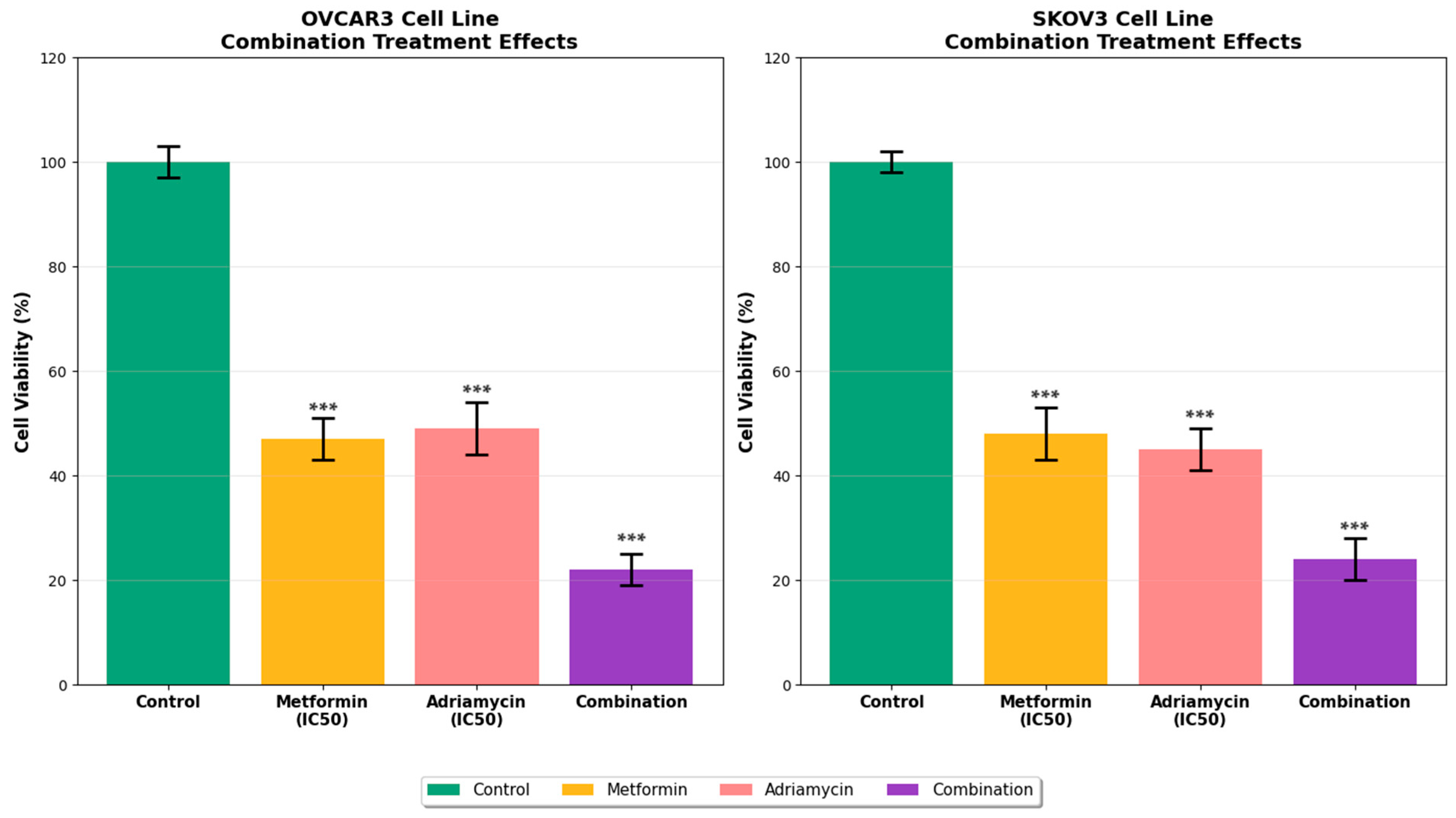

This study comprehensively evaluated the synergistic anticancer effects of the combination of metformin and adriamycin on the ovarian cancer cell lines OVCAR3 and SKOV3. The findings demonstrate that this combination exerts potent antiproliferative and apoptotic effects through multiple mechanisms. Metformin and adriamycin alone exhibited dose and time dependent cytotoxic effects in ovarian cancer cells, while the combination produced a synergistic response. MTT test results showed that the combination treatment significantly reduced cell viability in both cell lines compared to single drug treatments. While adriamycin is known to have potent anticancer activity alone [

4], our study demonstrated that its combination with metformin significantly enhanced this effect.

Adriamycin is an anthracycline chemotherapeutic agent that exerts anticancer effects by intercalating into DNA and inhibiting the topoisomerase II enzyme [

12]. However, the development of MDR and serious side effects such as cardiotoxicity limit its clinical use. In our study, the 48 h IC

50 value of adriamycin in OVCAR3 cells was 1.2 micromolar when administered alone, which is consistent with values reported in ovarian cancer cell lines [

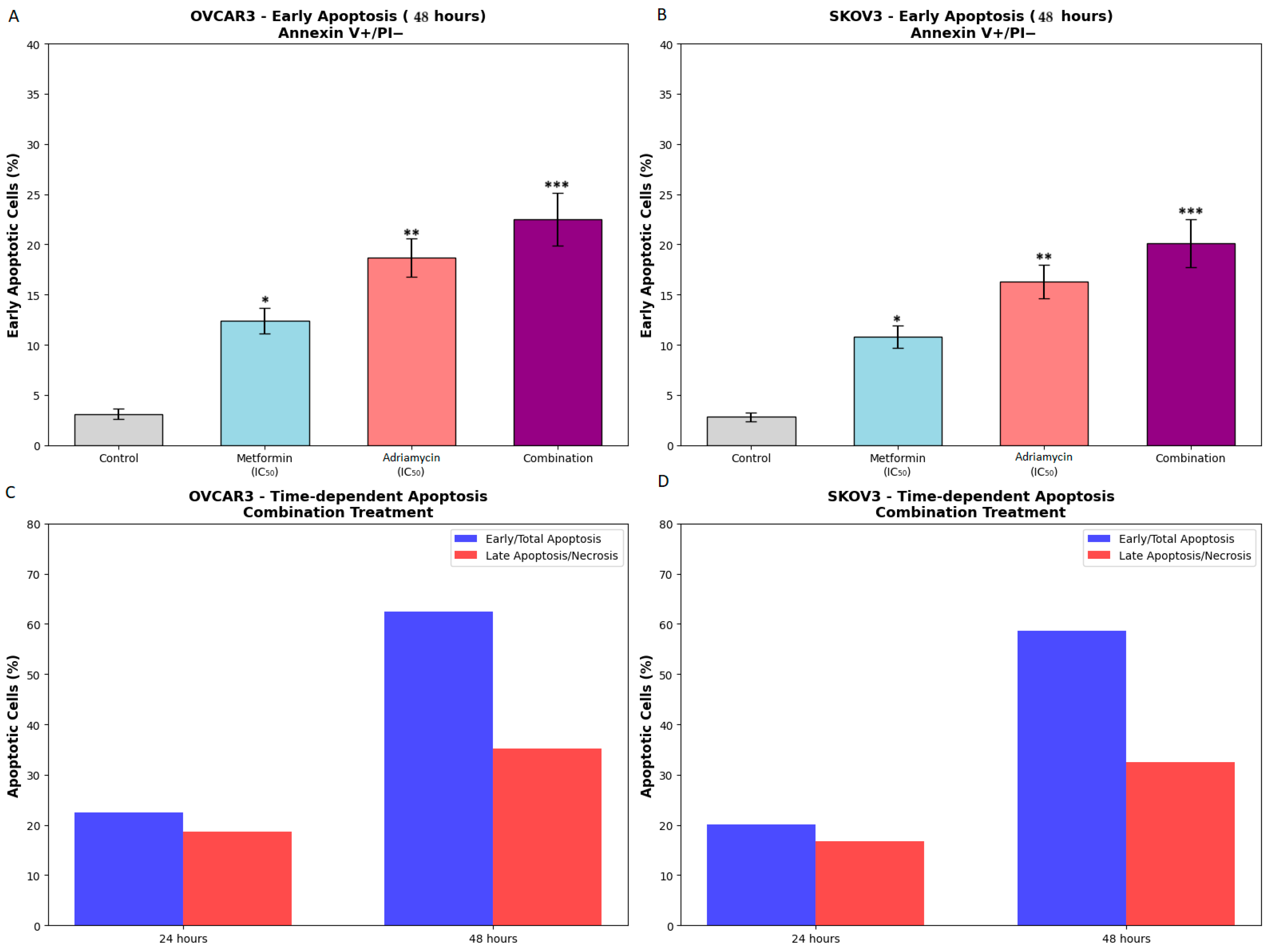

13]. Examination of apoptotic mechanisms revealed that the combination treatment activated both extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways. Flow cytometry analysis showed that the total apoptotic cell rate reached 62.5 percent in OVCAR3 and 58.7 percent in SKOV3 following combination treatment. This dramatic increase suggests that metformin potentiates the apoptotic effects of adriamycin. The apoptotic effect of adriamycin alone is well documented [

14], but the synergistic enhancement of this effect by metformin is an important finding [

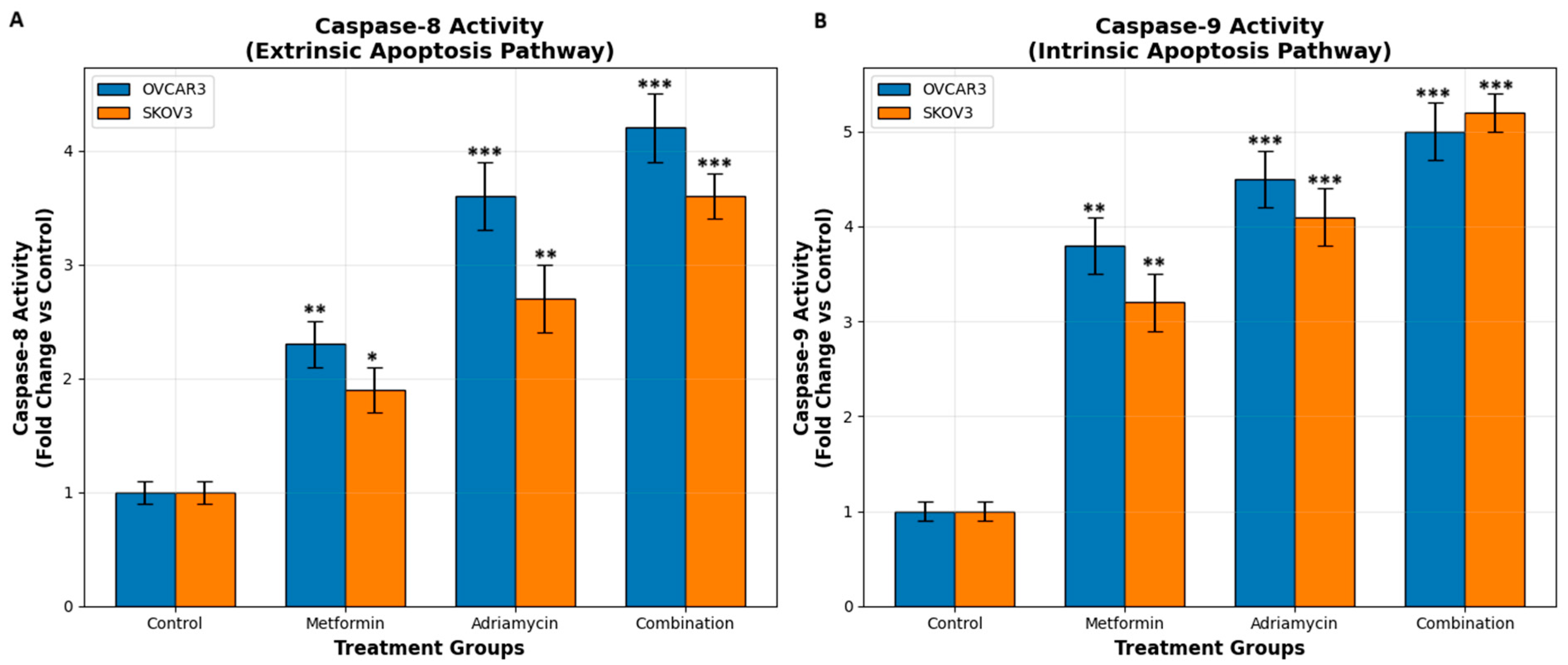

15]. Caspase activity analyses confirmed this observation. Combination treatment resulted in significantly greater activation of both caspase 8 and caspase 9 than single treatments [

16]. Adriamycin is known to primarily activate the intrinsic apoptosis pathway [

17], but in our study, metformin enhanced activation of both pathways.

Another important factor that may influence the differential apoptotic responses observed in OVCAR3 and SKOV3 cells is their p53 status. OVCAR3 cells harbor a mutant form of p53, whereas SKOV3 cells are completely p53 null and lack functional p53 protein. Since adriamycin induces apoptosis partly through DNA damage mediated p53 activation, the pronounced apoptotic response in SKOV3 despite the absence of p53 suggests that the combination treatment triggers p53 independent apoptotic mechanisms, including ROS driven mitochondrial injury and caspase 8 mediated extrinsic signaling. In contrast, mutant p53 in OVCAR3 may retain partial or altered transcriptional activity that contributes to apoptotic priming. These observations indicate that the metformin adriamycin combination activates both p53 dependent and p53 independent apoptotic pathways and may therefore be effective in cancers with differing p53 backgrounds.

Evaluation of oxidative stress parameters showed that the combination treatment caused a significant increase in NO and ROS production. Griess assay results revealed that NO levels in the combination group increased to 12.4 micromolar in OVCAR3 and 10.8 micromolar in SKOV3. Similarly, DCFH-DA fluorescence measurements showed that ROS levels reached hyperoxidative stress levels. Adriamycin induces oxidative stress through free radical formation [

18], and metformin has been shown to increase ROS pro-duction by inhibiting the mitochondrial respiratory chain [

19]. The convergence of these mechanisms likely explains the strong oxidative stress mediated by apoptotic response observed in the combination group. Although metformin showed clear cytotoxic and pro apoptotic effects in both ovarian cancer cell lines, the concentrations required to achieve these responses in vitro were higher than the plasma levels that can be reached in clinical use. Therapeutic plasma levels of metformin in patients rarely exceed sixty micromolar, whereas cultured cancer cells often require concentrations in the millimolar range due to differences in drug uptake, metabolic activity and the absence of a physiological tumor microenvironment. This situation has been described in many in vitro cancer studies and is considered a characteristic of two-dimensional culture systems rather than a limitation of the drug itself. It is known that concentrations well above clinical plasma levels (~20–40 µM) are required for the antitumor effects of metformin to occur under in vitro conditions. The 0–50 mM range used in this study also falls within this in vitro limitation. Therefore, the clinical relevance of the results obtained may be limited, and in vivo dose optimization is needed. The synergistic interaction with adriamycin also suggests that the therapeutic benefit of the combination may allow lower and clinically achievable doses of adriamycin in future in vivo studies.

qRT-PCR analyses confirmed that the combination therapy alters the expression of apoptosis-related genes at the transcriptional level. A significant reduction in Bcl 2 and Survivin expression and a marked increase in Bax and Caspase 3 expression were observed. Notably, the combination with metformin potentiated these transcriptional changes [

20]. Both the Chou Talalay and HSA synergy models confirmed significant pharmacological synergy, with CI values less than one and observed effects exceeding expected values. These results suggest that the metformin adriamycin combination may represent a promising therapeutic approach for ovarian cancer.

One of the major obstacles in ovarian cancer treatment is MDR to agents such as platinum and taxanes [

20,

21]. Although this study demonstrated that the combination of metformin and adriamycin can reduce the expression of anti-apoptotic markers that are associated with treatment resistance, it is important to note that the specific molecular components of MDR were not directly evaluated. Key transport proteins such as P glycoprotein, MRP1 and BCRP have central roles in the efflux of chemotherapeutic agents including adriamycin and their expression levels may strongly influence drug sensitivity. Although several studies suggest that metformin can modulate the activity of these transporters through AMPK related mechanisms, the present study did not examine these proteins experimentally. Therefore, the possibility that metformin enhances sensitivity to adriamycin partly through modulation of drug efflux pumps remains a hypothesis that needs to be addressed in future work. Although adriamycin is sometimes used to bypass these resistance mechanisms, it may not be sufficient alone. The combination of metformin and adriamycin may contribute to overcoming MDR by suppressing Bcl 2 and Survivin, proteins strongly associated with resistance [

22].

Furthermore, metformin inhibits the mTOR signaling pathway through AMPK activation [

8,

23,

24]. Given that mTOR overactivation contributes to chemoresistance, metformin induced AMPK activation and downstream mTOR inhibition [

25,

26,

27] may be another mechanism underlying the observed synergy. Although the involvement of AMPK and mTOR signaling pathways was discussed in relation to the potential mechanisms of synergy, this study did not directly measure the activation status of these pathways. Key markers such as phosphorylated AMPK, phosphorylated mTOR, S6 kinase and 4EBP1 were not evaluated at the protein level. Nevertheless, extensive evidence in the literature indicates that metformin can activate AMPK and suppress mTOR activity in many cancer models, which is consistent with the enhanced apoptotic response observed in our study. Confirmation of this mechanism will require future experiments that directly assess the phosphorylation status of these proteins in both ovarian cancer cell lines.

Oxidative stress induction is also a promising therapeutic strategy in cancer [

28,

29]. Adriamycin is a well-known ROS inducer that causes DNA damage and apoptosis through free radical formation. Metformin can also elevate mitochondrial ROS by inhibiting complex I [

30]. The extremely high ROS levels observed following combination treatment were likely due to the additive effects of both drugs on ROS production, contributing substantially to enhanced cell death [

31].

Bioinformatic analyses supported the clinical relevance of these findings. TCGA OV data showed that high Bcl 2 and Survivin expression correlated with poor survival outcomes, while high Bax and Caspase 3 were associated with better prognosis. STRING network analysis revealed strong functional interactions among these apoptotic regulators. These findings underscore the importance of the targeted pathways in ovarian cancer pathogenesis and therapy. Metformin may further enhance adriamycin responses by affecting energy metabolism [

32] and autophagy [

33]. The intersection of AMPK mTOR signaling with DNA damage induced p53 activation may also contribute to the synergy.

A major limitation of adriamycin therapy is dose-dependent cardiotoxicity [

5,

34,

35]. Achieving anticancer effects at lower adriamycin doses through synergy with metformin may reduce treatment related toxicity including cardiotoxicity [

36,

37]. Although one of the potential advantages of combining metformin with adriamycin is the possibility of lowering the dose of adriamycin and thereby reducing its cardiotoxic effects, the present study did not include any direct experimental assessment of cardiotoxicity. Adriamycin related cardiac injury is typically evaluated in cardiomyocyte models or in vivo systems through markers such as troponin release, mitochondrial dysfunction and changes in oxidative stress, none of which were examined here. Therefore, the suggestion that metformin may mitigate adriamycin induced cardiotoxicity remains a theoretical implication based on previous research rather than a conclusion supported by experimental data in this study. Future investigations using cardiac cell models or animal models will be essential to determine whether the synergistic antitumor effects observed here can be achieved with reduced cardiotoxicity in vivo. Overall, these findings suggest that co-administration of metformin with Adriamycin may enhance therapeutic efficacy in ovarian cancer while allowing reduced Adriamycin dosing and potentially lowering toxicity risks [

38,

39].

The present study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, all experiments were conducted exclusively in vitro using two ovarian cancer cell lines, which do not fully reflect the complexity of the tumor microenvironment, including stromal interactions, immune modulation, angiogenic signaling, and pharmacokinetic constraints. Second, the concentrations of metformin required to achieve cytotoxic and pro-apoptotic effects in vitro were substantially higher than clinically achievable plasma levels. Although this discrepancy is well documented in two-dimensional culture systems, it limits direct extrapolation of the results to clinical settings. Third, the molecular mechanisms proposed in this study were inferred primarily through mRNA level changes. This study assessed the mRNA level of apoptosis-related genes; however, protein expression or activation status was not analyzed. Therefore, the functional correlations of gene-level changes must be con-firmed by further protein-level studies. Fourth, oxidative and nitrosative stress measurements relied on DCFH-DA fluorescence and the Griess assay, which quantify total ROS and nitrite but do not identify mitochondrial versus cytosolic sources or characterize specific radical species. More comprehensive analyses, including mitochondrial superoxide detection (MitoSOX), glutathione quantification, or electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, would provide greater mechanistic clarity. Finally, although metformin has been associated with some cardioprotective effects in the literature, cardiac models or toxicity markers were not evaluated in this study. Therefore, the effects of the combination on cardiotoxicity should be investigated further in vivo studies. Consequently, metformin’s cardioprotective potential remains theoretical. Additional in vivo and ex vivo validation is necessary to determine whether the synergistic antitumor effects translate into favorable toxicity profiles.

Future studies should evaluate the efficacy and safety of the metformin–adriamycin combination in three-dimensional spheroid cultures and in vivo ovarian cancer models to better replicate physiological drug exposure, metabolic gradients, and tumor stroma interactions. Dose-reduction strategies for adriamycin should be systematically investigated to determine whether synergy observed in vitro can indeed lower anthracycline toxicity in vivo. Protein-level validation using Western blotting, phospho-protein profiling, and pathway inhibition experiments will be essential to confirm the molecular mechanisms suggested by gene expression analyses. Although literature suggests that metformin may affect some MDR pump related pathways, P-gp/MRP/BCRP levels were not assessed in this study. Therefore, potential changes in MDR transporters should be confirmed by future protein-level analyses. Given the pronounced oxidative and nitrosative stress induced by the combination therapy, future research should distinguish mitochondrial versus cytosolic ROS sources and explore redox dependent signaling pathways. Finally, cardiotoxicity-focused studies using cardiomyocyte cultures or in vivo cardiac function assays will be crucial to determine whether metformin can mitigate adriamycin-induced cardiac injury while pre-serving anticancer activity.

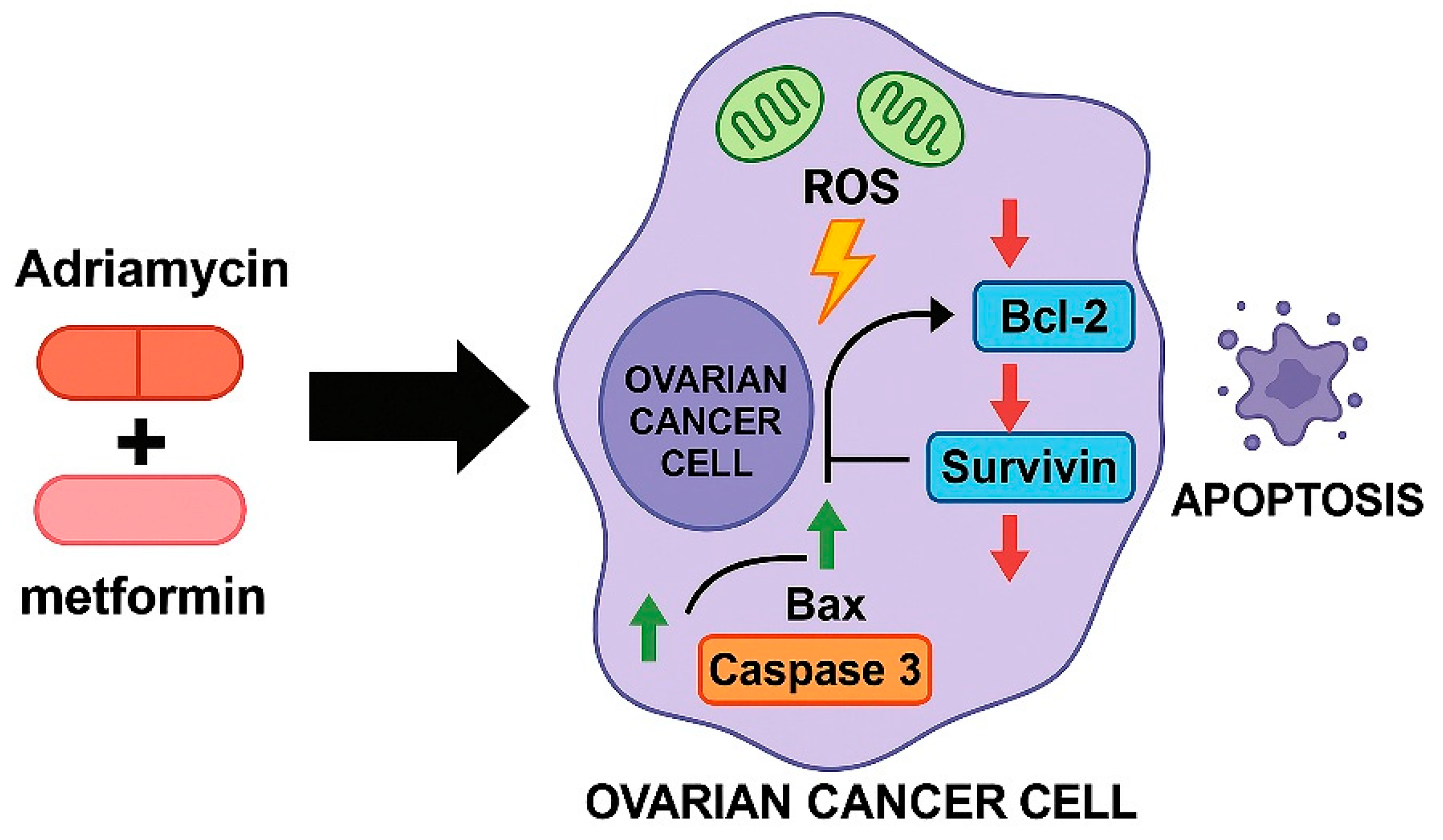

As illustrated in

Figure 12, the combined treatment with metformin and adriamycin promotes a coordinated apoptotic response by enhancing mitochondrial ROS generation and altering the balance of key apoptosis regulating genes. Increased ROS production, together with the upregulation of Bax and Caspase 3 and the suppression of Bcl 2 and Survivin, creates a pro apoptotic intracellular environment that facilitates extensive cell death. This integrated model supports the mechanistic basis of the strong synergistic anticancer effect observed in OVCAR3 and SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells.

In this study, the different sensitivity profiles observed between OVCAR3 and SKOV3 cell lines to low-, medium-, and high-dose combination therapies may be explained by differences in molecular characteristics specific to the cell lines. It is particularly noteworthy that OVCAR3 cells exhibited a higher sensitivity to combination therapies compared to SKOV3. The underlying mechanisms for this difference include (1) differences in p53 status (mutant p53 in OVCAR3 vs. p53 null in SKOV3), (2) differences in the expression levels of apoptosis regulatory proteins, (3) variations in drug transport mechanisms, and (4) differences in metabolic adaptation capacities. The higher basal apoptosis rates and increased oxidative stress sensitivity of OVCAR3 cells may explain this cell line’s greater sensitivity to combination therapy. On the other hand, the more aggressive phenotype and higher proliferation capacity of SKOV3 cells may more effectively activate treatment resistance mechanisms. These findings support the need to personalize combination therapy strategies across patient subgroups. In future studies, elucidating the molecular basis of differences in sensitivity between these cell lines is critical for the identification of biomarkers that can predict response to treatment.