A Supervised Learning Approach for Accurate and Efficient Identification of Chikungunya Virus Lineages and Signature Mutations

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- We constructed a high-quality CHIKV genome dataset with fine-grained lineage labels using a hierarchical classification pipeline that combines rapid Position Weight Matrix (PWM) screening, targeted machine learning refinement, and phylogenetic validation.

- (2)

- We developed and evaluated multiple machine learning models for discriminating eight CHIKV lineages, achieving near-perfect accuracy on high-coverage whole-genome data and maintaining robust performance on low-coverage sequences.

- (3)

- We employed SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), an interpretability framework, to identify and validate key amino acid substitutions associated with specific lineages, thereby bridging data-driven predictions with established biological knowledge and offering novel insights into CHIKV evolution and adaptation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.2. Evolutionary Diversity Analysis

2.3. Hierarchical Lineage Assignment for Unlabeled Samples

2.3.1. Construction of a Representative Reference Sequence Set

2.3.2. Development of Complementary Classification Models

- (1)

- Position Weight Matrix (PWM) Model

- (2)

- Machine Learning (ML) Models

2.3.3. Hierarchical Lineage Assignment Workflow

2.4. Construction of High-Precision Lineage Identification Models

2.4.1. Dataset Partitioning and Balancing

2.4.2. Feature Dimensionality Reduction and Key Site Selection

2.4.3. Model Training and Performance Evaluation

2.5. Model Interpretability Analysis

- (1)

- The multi-class lineage classification problem was decomposed into binary tasks. For each target lineage, labels were binarized into “target lineage” versus “other lineages”. A separate classifier was trained for each binary task on the amino acid feature training set.

- (2)

- For each binary model, SHAP values were computed for every amino acid feature site across training samples. The sign of a SHAP value indicates whether a specific amino acid promotes (positive) or suppresses (negative) prediction toward the target lineage, while its magnitude reflects the degree of the influence. Sites were then ranked in descending order based on their mean absolute SHAP value.

- (3)

- SHAP summary plots were generated to visualize the overall impact and contribution direction of the most important sites. Feature dependence plots were generated to illustrate how different amino acid types at individual key sites influence the SHAP values for a given lineage.

3. Results

3.1. Landscape of Genetic Diversity Across CHIKV Genomic Regions

3.2. Hierarchical Lineage Assignment

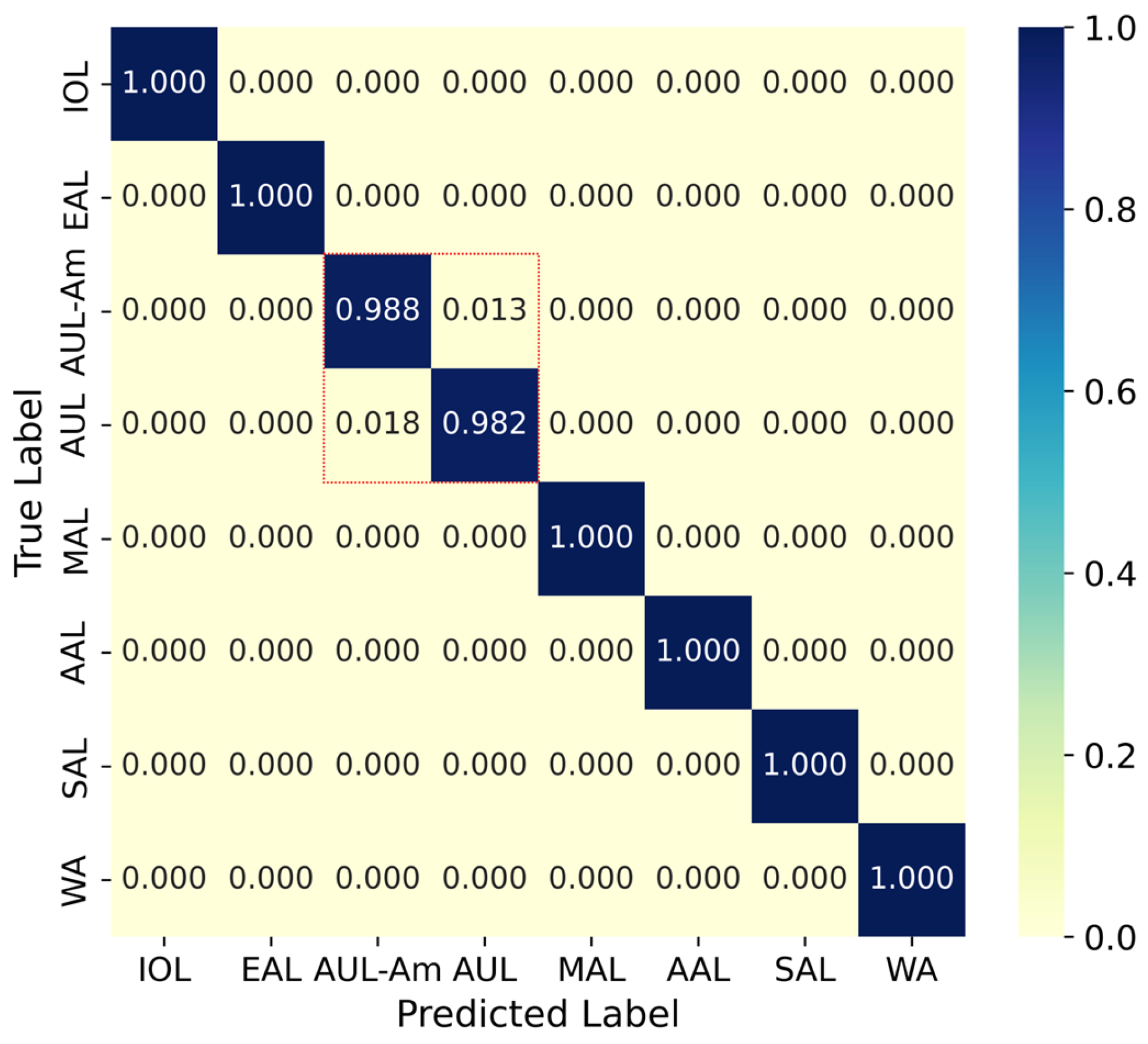

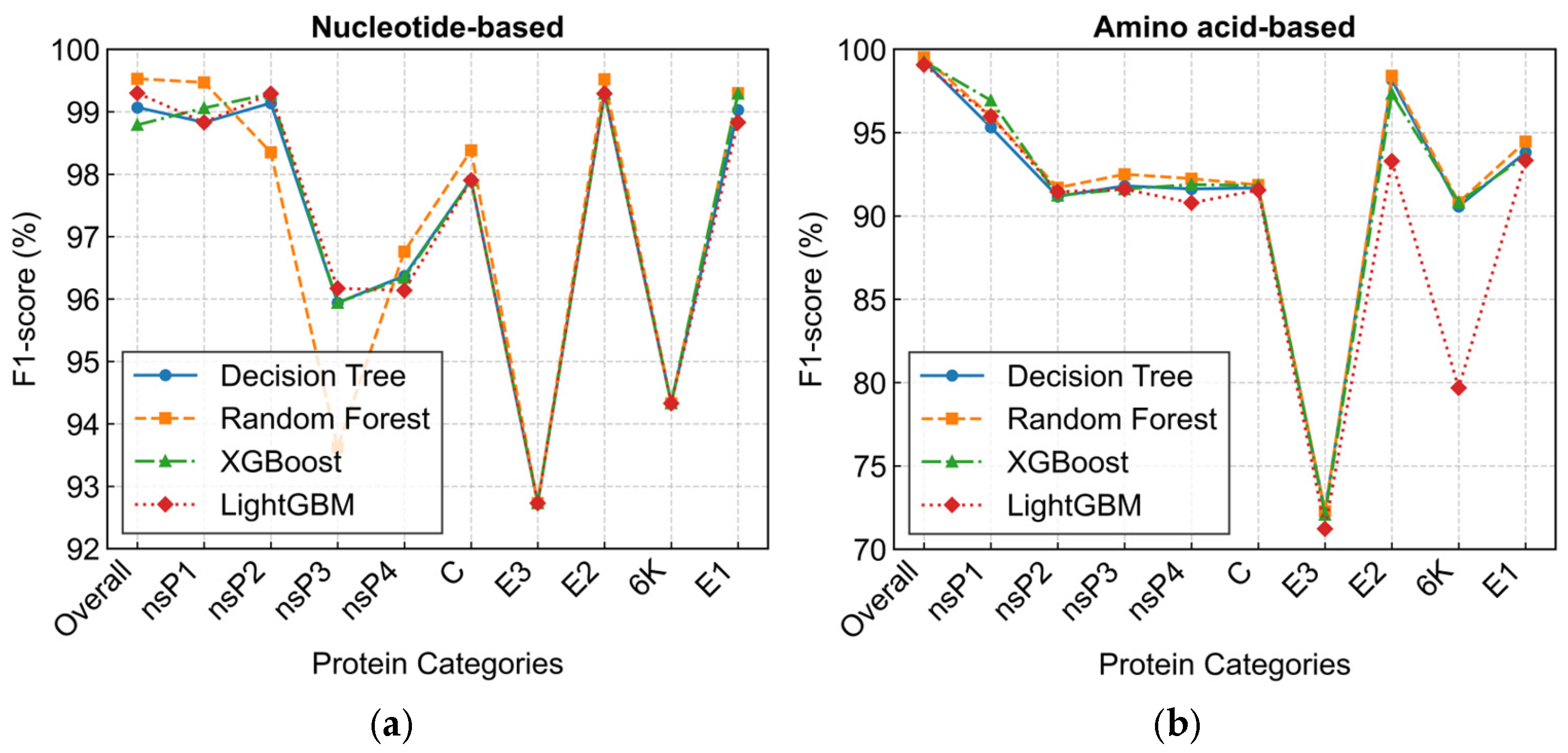

3.3. Performance of High-Precision Identification Models

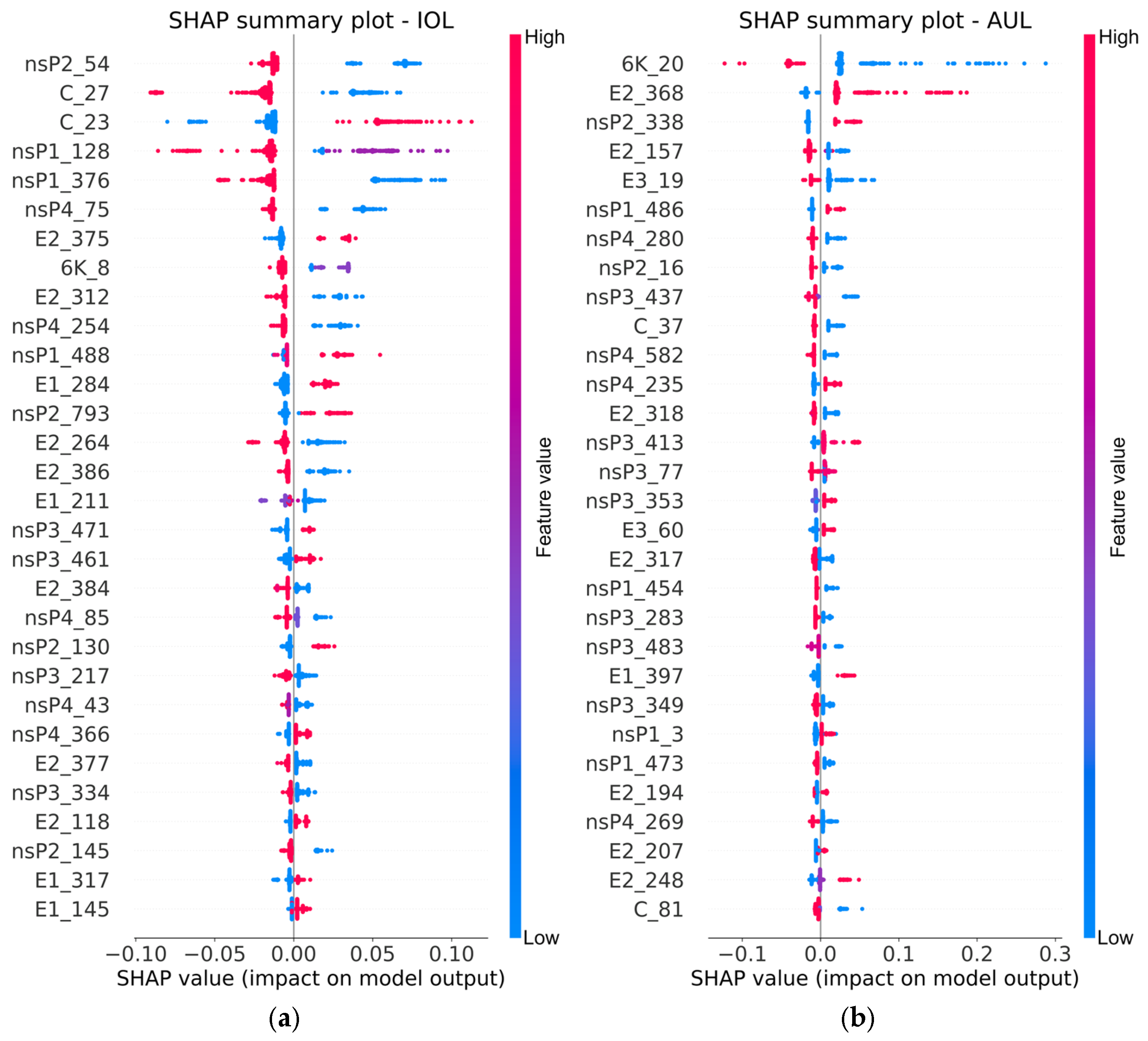

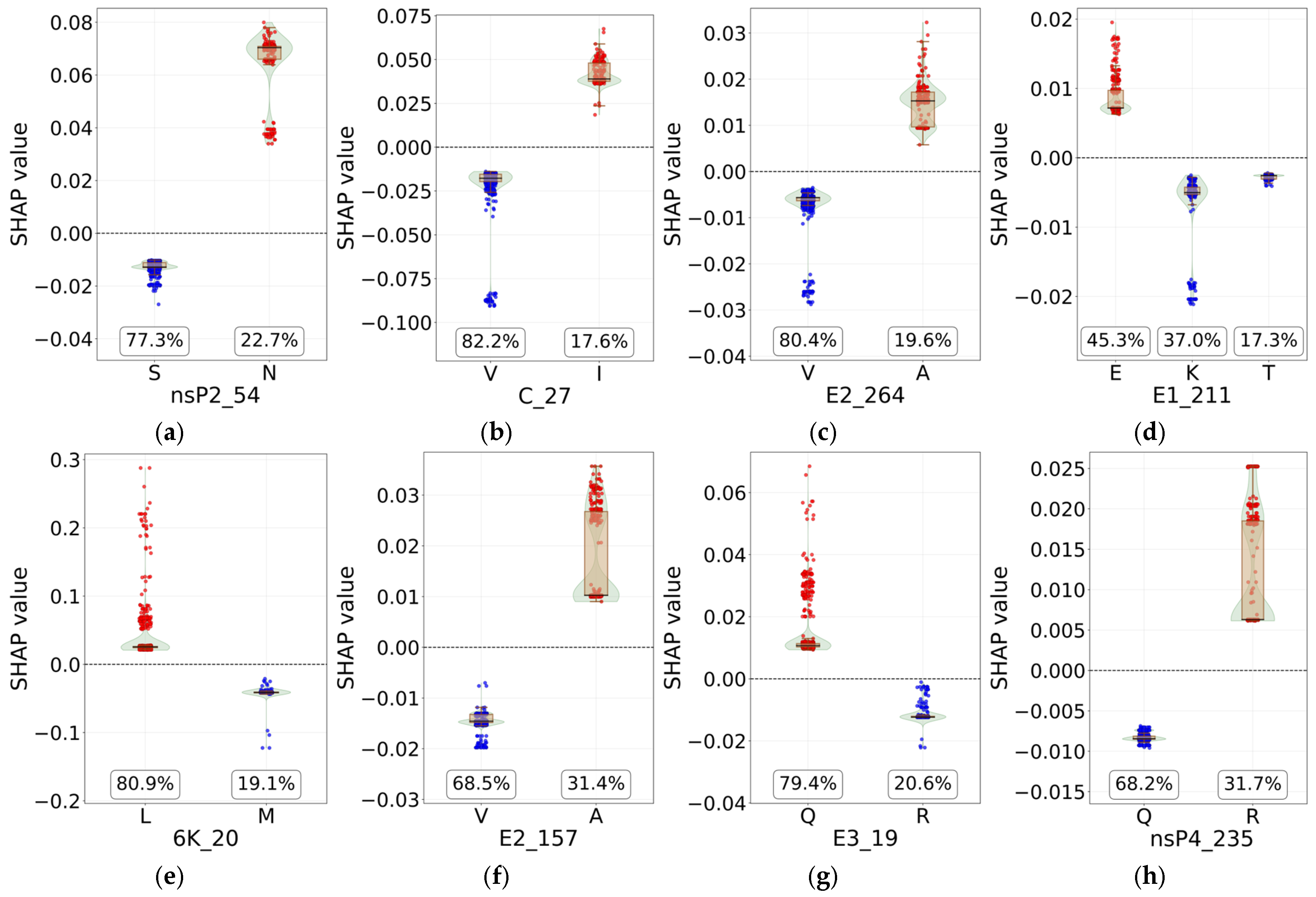

3.4. Identification of Signature Mutations from SHAP Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHIKV | Chikungunya virus |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| CHIKF | Chikungunya fever |

| ORFs | Open reading frames |

| UTRs | Untranslated regions |

| nsP | Non-structural proteins |

| ECSA | East/Central/South African |

| WA | West African |

| IOL | Indian Ocean lineage |

| PWM | Position weight matrix |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| GISAID | Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data |

| SAL | South American lineage |

| EAL | Eastern African lineage |

| AAL | African/Asian lineage |

| AUL | Asian Urban lineage |

| AUL-Am | AUL–America |

| sECSA | Sister Taxa to ECSA |

| MDD | Maximum diversity downsampling |

| ML | Machine learning |

| DT | Decision tree |

| RF | Random forest |

| XGB | XGBoost |

| LGB | LightGBM |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

References

- de Souza, W.M.; Lecuit, M.; Weaver, S.C. Chikungunya virus and other emerging arthritogenic alphaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettis, A.A.; L’Azou Jackson, M.; Yoon, I.K.; Breugelmans, J.G.; Goios, A.; Gubler, D.J.; Powers, A.M. The global epidemiology of chikungunya from 1999 to 2020: A systematic literature review to inform the development and introduction of vaccines. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Chang, J.; Cortes, F.H.; Ha, C.; Villalpando, J.; Castillo, I.N.; Galvez, R.I.; Grifoni, A.; Sette, A.; Romero-Vivas, C.M.; et al. Chikungunya virus-specific CD4(+) T cells are associated with chronic chikungunya viral arthritic disease in humans. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, C.; Elsinga, J.; Fokkema, A.; Berenschot, K.; Gerstenbluth, I.; Duits, A.; Lourents, N.; Halabi, Y.; Burgerhof, J.; Bailey, A.; et al. Long-term Chikungunya sequelae and quality of life 2.5 years post-acute disease in a prospective cohort in Curacao. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro Dos Santos, G.; Jawed, F.; Mukandavire, C.; Deol, A.; Scarponi, D.; Mboera, L.E.G.; Seruyange, E.; Poirier, M.J.P.; Bosomprah, S.; Udeze, A.O.; et al. Global burden of chikungunya virus infections and the potential benefit of vaccination campaigns. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2342–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, W.M.; de Lima, S.T.S.; Simoes Mello, L.M.; Candido, D.S.; Buss, L.; Whittaker, C.; Claro, I.M.; Chandradeva, N.; Granja, F.; de Jesus, R.; et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics and recurrence of chikungunya virus in Brazil: An epidemiological study. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e319–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinedu Eneh, S.; Uwishema, O.; Nazir, A.; El Jurdi, E.; Faith Olanrewaju, O.; Abbass, Z.; Mustapha Jolayemi, M.; Mina, N.; Kseiry, L.; Onyeaka, H. Chikungunya outbreak in Africa: A review of the literature. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 3545–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhrbier, A. Rheumatic manifestations of chikungunya: Emerging concepts and interventions. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2019, 15, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadungsombat, J.; Imad, H.A.; Nakayama, E.E.; Leaungwutiwong, P.; Ramasoota, P.; Nguitragool, W.; Matsee, W.; Piyaphanee, W.; Shioda, T. Spread of a Novel Indian Ocean Lineage Carrying E1-K211E/E2-V264A of Chikungunya Virus East/Central/South African Genotype across the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Africa. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, W.M.; Ribeiro, G.S.; de Lima, S.T.S.; de Jesus, R.; Moreira, F.R.R.; Whittaker, C.; Sallum, M.A.M.; Carrington, C.V.F.; Sabino, E.C.; Kitron, U.; et al. Chikungunya: A decade of burden in the Americas. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2024, 30, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, E.C.; Fonseca, V.; Xavier, J.; Adelino, T.; Morales Claro, I.; Fabri, A.; Marques Macario, E.; Viniski, A.E.; Campos Souza, C.L.; Gomes da Costa, E.S.; et al. Short report: Introduction of chikungunya virus ECSA genotype into the Brazilian Midwest and its dispersion through the Americas. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khongwichit, S.; Chansaenroj, J.; Chirathaworn, C.; Poovorawan, Y. Chikungunya virus infection: Molecular biology, clinical characteristics, and epidemiology in Asian countries. J. Biomed. Sci. 2021, 28, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, S.C.; Lecuit, M. Chikungunya virus and the global spread of a mosquito-borne disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krambrich, J.; Mihalic, F.; Gaunt, M.W.; Bohlin, J.; Hesson, J.C.; Lundkvist, A.; de Lamballerie, X.; Li, C.; Shi, W.; Pettersson, J.H. The evolutionary and molecular history of a chikungunya virus outbreak lineage. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Xia, B.; Wang, J.; Gao, R.; Ren, H. Host-adaptive mutations in Chikungunya virus genome. Virulence 2024, 15, 2401985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.C.; Chen, R.; Diallo, M. Chikungunya Virus: Role of Vectors in Emergence from Enzootic Cycles. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020, 65, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsetsarkin, K.A.; Weaver, S.C. Sequential adaptive mutations enhance efficient vector switching by Chikungunya virus and its epidemic emergence. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomeeusen, K.; Daniel, M.; LaBeaud, D.A.; Gasque, P.; Peeling, R.W.; Stephenson, K.E.; Ng, L.F.P.; Arien, K.K. Chikungunya fever. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounce, B.C.; Cesaro, T.; Vlajnic, L.; Vidina, A.; Vallet, T.; Weger-Lucarelli, J.; Passoni, G.; Stapleford, K.A.; Levraud, J.P.; Vignuzzi, M. Chikungunya Virus Overcomes Polyamine Depletion by Mutation of nsP1 and the Opal Stop Codon To Confer Enhanced Replication and Fitness. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00344-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R.; Manakkadan, A.; Mudaliar, P.; Joseph, I.; Sivakumar, K.C.; Nair, R.R.; Sreekumar, E. Correlation of phylogenetic clade diversification and in vitro infectivity differences among Cosmopolitan genotype strains of Chikungunya virus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 37, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, T.; Dia, A.; Savreux, Q.; Pommier de Santi, V.; de Lamballerie, X.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Simon, F. Emergence of Indian lineage of ECSA chikungunya virus in Djibouti, 2019. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 108, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamwaya, D.K.; Otiende, M.; Omuoyo, D.O.; Githinji, G.; Karanja, H.K.; Gitonga, J.N.; de Laurent, Z.R.; Otieno, J.R.; Sang, R.; Kamau, E.; et al. Endemic chikungunya fever in Kenyan children: A prospective cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, H.; El Karsany, M.; Adam, A.; Idriss, M.I.; Alzain, M.A.; Alfakiyousif, M.E.A.; Mohamed, R.; Mahmoud, I.; Albadri, O.; Mahmoud, S.A.A.; et al. “Kankasha” in Kassala: A prospective observational cohort study of the clinical characteristics, epidemiology, genetic origin, and chronic impact of the 2018 epidemic of Chikungunya virus infection in Kassala, Sudan. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maljkovic Berry, I.; Eyase, F.; Pollett, S.; Konongoi, S.L.; Joyce, M.G.; Figueroa, K.; Ofula, V.; Koka, H.; Koskei, E.; Nyunja, A.; et al. Global Outbreaks and Origins of a Chikungunya Virus Variant Carrying Mutations Which May Increase Fitness for Aedes aegypti: Revelations from the 2016 Mandera, Kenya Outbreak. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, P.; Hao, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Ma, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, N. Emerging West African Genotype Chikungunya Virus in Mosquito Virome. Virulence 2025, 16, 2444686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsetsarkin, K.A.; Chen, R.; Yun, R.; Rossi, S.L.; Plante, K.S.; Guerbois, M.; Forrester, N.; Perng, G.C.; Sreekumar, E.; Leal, G.; et al. Multi-peaked adaptive landscape for chikungunya virus evolution predicts continued fitness optimization in Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawman, D.W.; Carpentier, K.S.; Fox, J.M.; May, N.A.; Sanders, W.; Montgomery, S.A.; Moorman, N.J.; Diamond, M.S.; Morrison, T.E. Mutations in the E2 Glycoprotein and the 3′ Untranslated Region Enhance Chikungunya Virus Virulence in Mice. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00816-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumence, E.; Piorkowski, G.; Traversier, N.; Amaral, R.; Vincent, M.; Mercier, A.; Ayhan, N.; Souply, L.; Pezzi, L.; Lier, C.; et al. Genomic insights into the re-emergence of chikungunya virus on Reunion Island, France, 2024 to 2025. Eurosurveillance 2025, 30, 2500344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Sobolik, E.B.; May, N.A.; Wang, S.; Fayed, A.; Vyshenska, D.; Drobish, A.M.; Parks, M.G.; Lello, L.S.; Merits, A.; et al. Mutations in chikungunya virus nsP4 decrease viral fitness and sensitivity to the broad-spectrum antiviral 4′-Fluorouridine. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1012859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, K.; de Roo, A.M.; Louwsma, T.; Hofstra, H.S.; Gurgel do Amaral, G.S.; Vondeling, G.T.; Postma, M.J.; Freriks, R.D. Clinical outcomes of chikungunya: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegado, R.; Mendes Neto, N.N.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Fregni, F. Chikungunya crisis in the Americas: A comprehensive call for research and innovation. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2024, 34, 100758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, V.; Libin, P.J.K.; Theys, K.; Faria, N.R.; Nunes, M.R.T.; Restovic, M.I.; Freire, M.; Giovanetti, M.; Cuypers, L.; Nowe, A.; et al. A computational method for the identification of Dengue, Zika and Chikungunya virus species and genotypes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadfield, J.; Megill, C.; Bell, S.M.; Huddleston, J.; Potter, B.; Callender, C.; Sagulenko, P.; Bedford, T.; Neher, R.A. Nextstrain: Real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 4121–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Toole, A.; Scher, E.; Underwood, A.; Jackson, B.; Hill, V.; McCrone, J.T.; Colquhoun, R.; Ruis, C.; Abu-Dahab, K.; Taylor, B.; et al. Assignment of epidemiological lineages in an emerging pandemic using the pangolin tool. Virus Evol. 2021, 7, veab064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.P.; Cohen, S.; Zhao, M.; Madeleine, M.; Payne, T.H.; Lybrand, T.P.; Geraghty, D.E.; Jerome, K.R.; Corey, L. Using Haplotype-Based Artificial Intelligence to Evaluate SARS-CoV-2 Novel Variants and Mutations. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e230191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zyl, D.J.; Dunaiski, M.; Tegally, H.; Baxter, C.; de Oliveira, T.; Xavier, J.S.; Group, I.A.R.S. Craft: A machine learning approach to dengue subtyping. Bioinform. Adv. 2025, 5, vbaf224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, C.; Kongkitimanon, K.; Frank, S.; Holzer, M.; Paraskevopoulou, S.; Richard, H. VirusWarn: A mutation-based early warning system to prioritize concerning SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus variants from sequencing data. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Sun, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Ru, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Hao, R.; Bian, P.; et al. SVLearn: A dual-reference machine learning approach enables accurate cross-species genotyping of structural variants. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; De Clercq, E.; Li, G. Towards Efficient and Accurate SARS-CoV-2 Genome Sequence Typing Based on Supervised Learning Approaches. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xie, L. Advancing neural network calibration: The role of gradient decay in large-margin Softmax optimization. Neural. Netw. 2024, 178, 106457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Ma, Y.; Tan, J.; Chen, R.; Men, K. Enhanced predictability and interpretability of COVID-19 severity based on SARS-CoV-2 genomic diversity: A comprehensive study encompassing four years of data. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.S.; Amorim, V.M.F.; Soares, E.P.; de Souza, R.F.; Guzzo, C.R. Antagonistic Trends Between Binding Affinity and Drug-Likeness in SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitors Revealed by Machine Learning. Viruses 2025, 17, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junge, M.R.J.; Dettori, J.R. ROC Solid: Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) Curves as a Foundation for Better Diagnostic Tests. Glob. Spine J. 2018, 8, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBroome, J.; de Bernardi Schneider, A.; Roemer, C.; Wolfinger, M.T.; Hinrichs, A.S.; O’Toole, A.N.; Ruis, C.; Turakhia, Y.; Rambaut, A.; Corbett-Detig, R. A framework for automated scalable designation of viral pathogen lineages from genomic data. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spicher, T.; Delitz, M.; Schneider, A.B.; Wolfinger, M.T. Dynamic Molecular Epidemiology Reveals Lineage-Associated Single-Nucleotide Variants That Alter RNA Structure in Chikungunya Virus. Genes 2021, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.B.; Ochsenreiter, R.; Hostager, R.; Hofacker, I.L.; Janies, D.; Wolfinger, M.T. Updated Phylogeny of Chikungunya Virus Suggests Lineage-Specific RNA Architecture. Viruses 2019, 11, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thannickal, S.A.; Battini, L.; Spector, S.N.; Noval, M.G.; Alvarez, D.E.; Stapleford, K.A. Changes in the chikungunya virus E1 glycoprotein domain II and hinge influence E2 conformation, infectivity, and virus-receptor interactions. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0067924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahshan, Z.; Yavits, L. ViTAL: Vision TrAnsformer based Low coverage SARS-CoV-2 lineage assignment. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanasundram, J.; Zawawi, Z.M.; Kamel, K.A.; Aroidoss, E.T.; Ellan, K.; Anasir, M.I.; Azizan, M.A.; Zulkifli, M.M.S.; Zain, R.M. Emergence of ECSA-IOL E1-K211E/E2-V264A Lineage of Chikungunya virus during Malaysian 2021 outbreak. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein | Location (nts) | Protein Length | Nucleotide Diversity | Amino Acid Diversity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphic Sites (Ratio) | Median (Q1, Q3) | Polymorphic Sites (Ratio) | Median (Q1, Q3) | |||

| nsP1 | 77–1681 | 534 | 974 (60.69%) | 0.0006 (0, 0.0024) | 330 (61.80%) | 0.0003 (0, 0.0012) |

| nsP2 | 1682–4075 | 797 | 1398 (58.40%) | 0.0003 (0, 0.0021) | 433 (54.33%) | 0.0003 (0, 0.0009) |

| nsP3 | 4076–5665 | 529 | 1141 (71.76%) | 0.0009 (0, 0.0124) | 389 (73.53%) | 0.0009 (0, 0.0018) |

| nsP4 | 5666–7501 | 611 | 1101 (59.97%) | 0.0003 (0, 0.0033) | 340 (55.65%) | 0.0003 (0, 0.0009) |

| C | 7567–8349 | 260 | 445 (56.83%) | 0.0003 (0, 0.0024) | 140 (53.85%) | 0.0003 (0, 0.0012) |

| E3 | 8350–8541 | 63 | 126 (65.63%) | 0.0009 (0, 0.0136) | 41 (65.08%) | 0.0009 (0, 0.0030) |

| E2 | 8542–9810 | 422 | 852 (67.14%) | 0.0009 (0, 0.0100) | 303 (71.80%) | 0.0009(0, 0.0021) |

| 6K | 9811–9993 | 60 | 124 (67.76%) | 0.0009 (0, 0.0036) | 44 (73.33%) | 0.0009 (0, 0.0021) |

| E1 | 9994–11,313 | 439 | 848 (64.24%) | 0.0009 (0, 0.0031) | 288 (65.60%) | 0.0006 (0, 0.0012) |

| Method | Evaluation Metrics | Feature | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide-Based | Amino Acid-Based | ||

| Decision Tree | Precision (%) | 99.10 | 99.32 |

| Recall (%) | 99.07 | 99.30 | |

| F1-score (%) | 99.07 | 99.29 | |

| AUC | 0.9960 | 0.9960 | |

| Random Forest | Precision (%) | 99.53 | 99.54 |

| Recall (%) | 99.53 | 99.53 | |

| F1-score (%) | 99.53 | 99.52 | |

| AUC | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| XGBoost | Precision (%) | 98.85 | 99.31 |

| Recall (%) | 98.83 | 99.30 | |

| F1-score (%) | 98.79 | 99.26 | |

| AUC | 1.0000 | 0.9999 | |

| LightGBM | Precision (%) | 99.32 | 99.07 |

| Recall (%) | 99.30 | 99.07 | |

| F1-score (%) | 99.30 | 99.06 | |

| AUC | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miao, M.; Fan, Y.; Tan, J.; Hu, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, G.; Men, K. A Supervised Learning Approach for Accurate and Efficient Identification of Chikungunya Virus Lineages and Signature Mutations. Biology 2025, 14, 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121736

Miao M, Fan Y, Tan J, Hu X, Ma Y, Li G, Men K. A Supervised Learning Approach for Accurate and Efficient Identification of Chikungunya Virus Lineages and Signature Mutations. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121736

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiao, Miao, Yameng Fan, Jiao Tan, Xiaobin Hu, Yonghong Ma, Guangdi Li, and Ke Men. 2025. "A Supervised Learning Approach for Accurate and Efficient Identification of Chikungunya Virus Lineages and Signature Mutations" Biology 14, no. 12: 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121736

APA StyleMiao, M., Fan, Y., Tan, J., Hu, X., Ma, Y., Li, G., & Men, K. (2025). A Supervised Learning Approach for Accurate and Efficient Identification of Chikungunya Virus Lineages and Signature Mutations. Biology, 14(12), 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121736