Less Severe Inflammation in Cyclic GMP–AMP Synthase (cGAS)-Deficient Mice with Rabies, Impact of Mitochondrial Injury, and Gut–Brain Axis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal, Viral Preparation, and Animal Model

2.2. Mouse Sample Analysis

2.3. Fecal Microbiome Analysis

2.4. The In Vitro Experiments

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

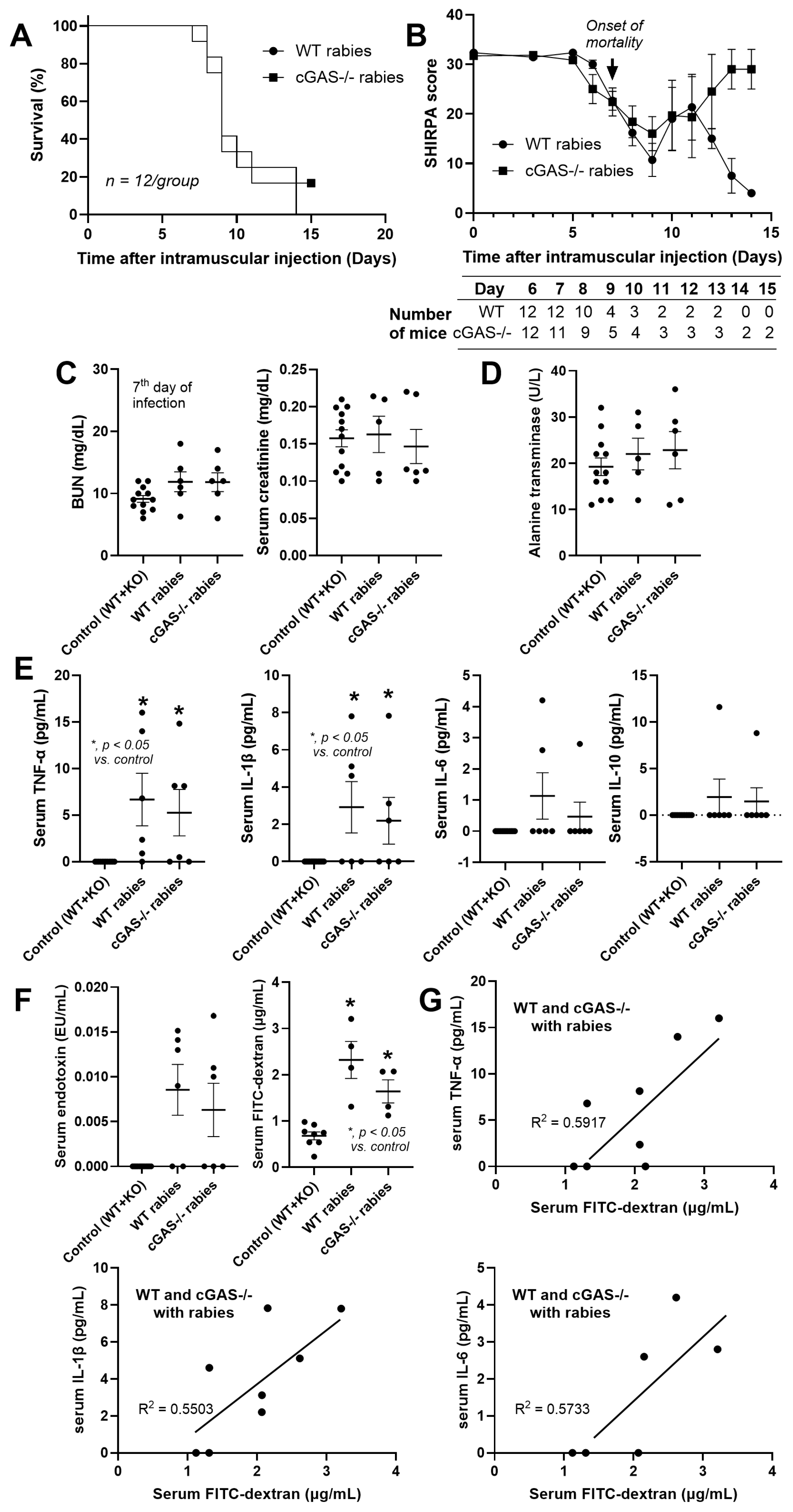

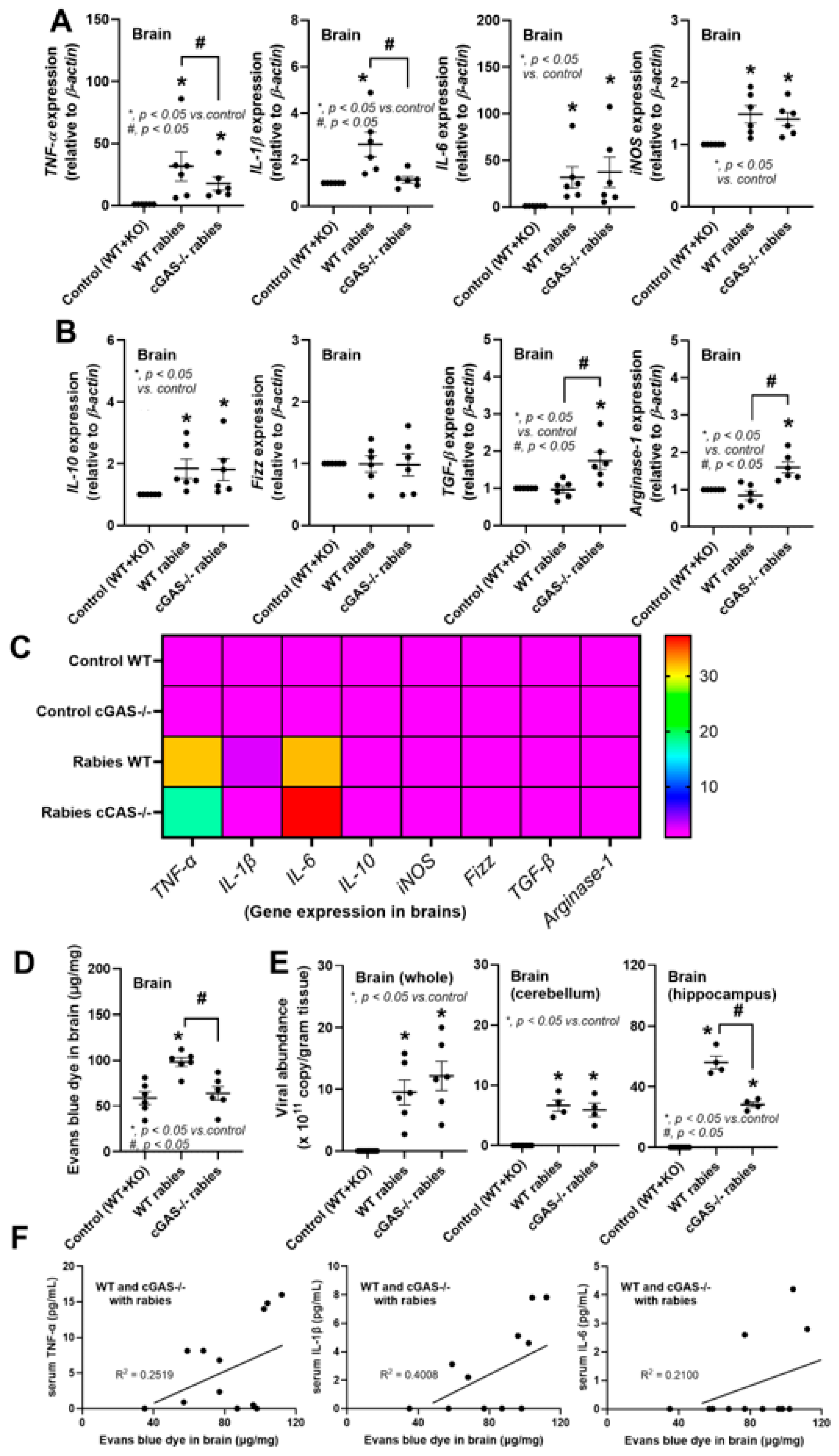

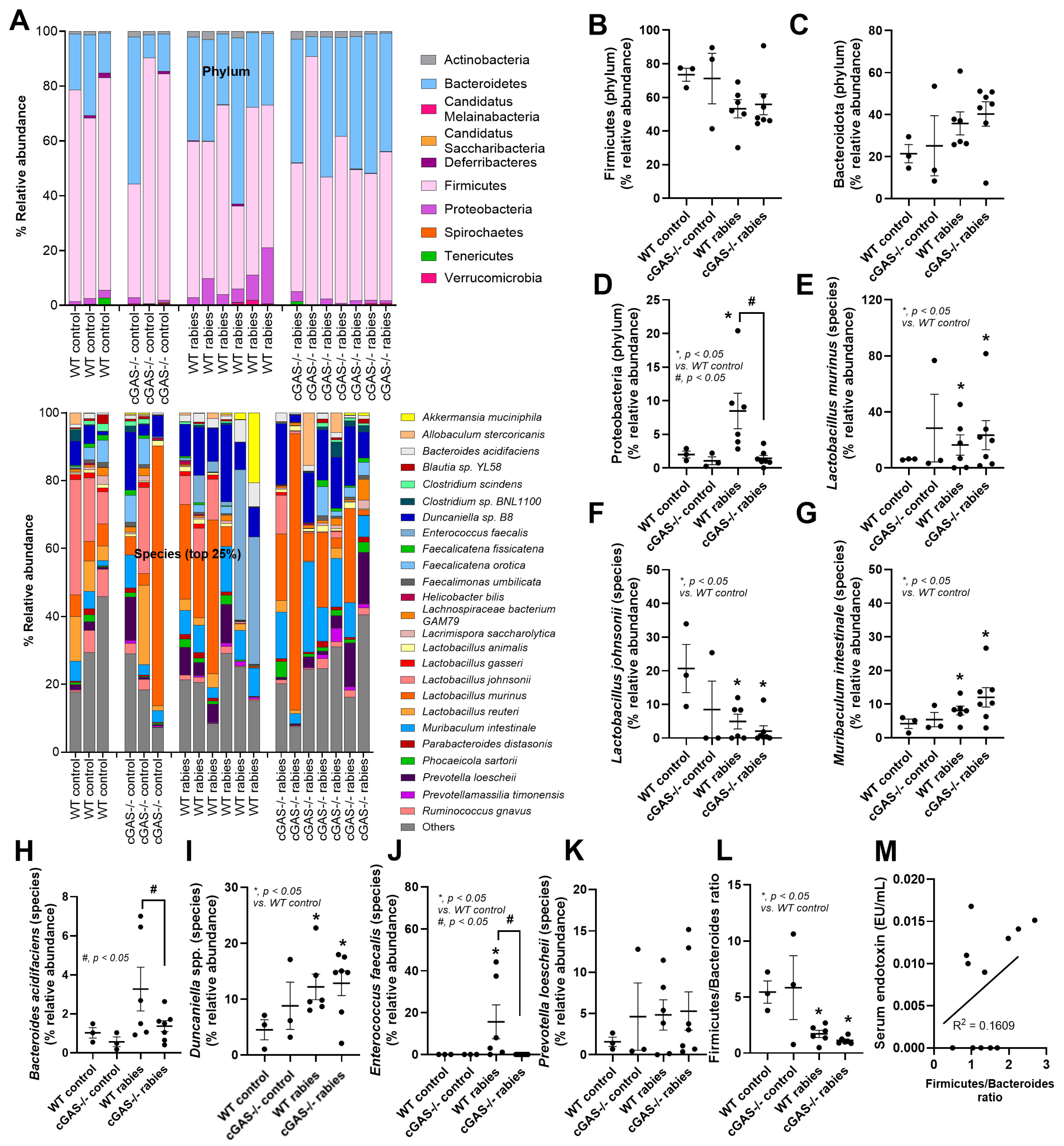

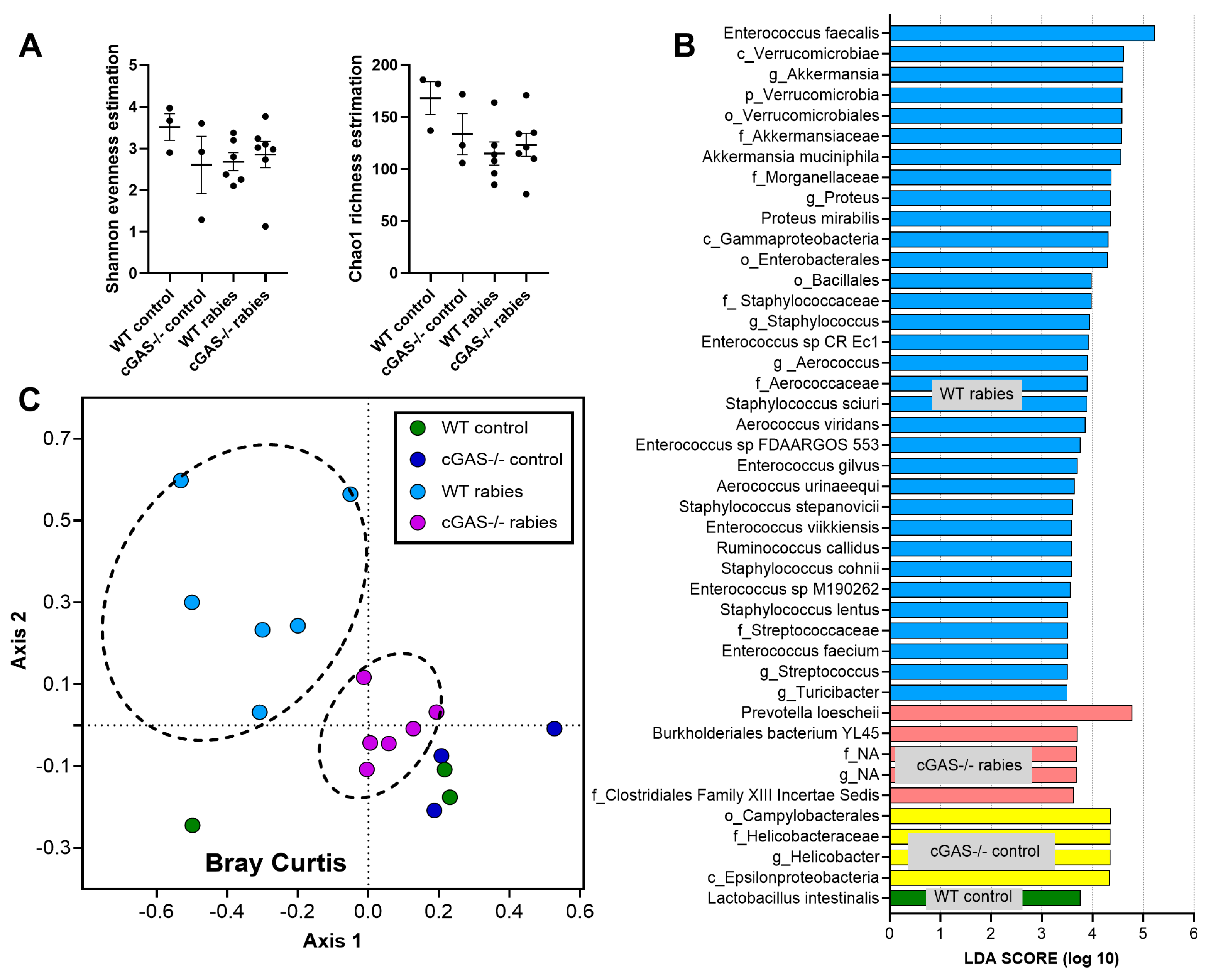

3.1. Less Severe Brain Inflammation and Gut Dysbiosis in Rabies-Infected cGAS-/- Mice

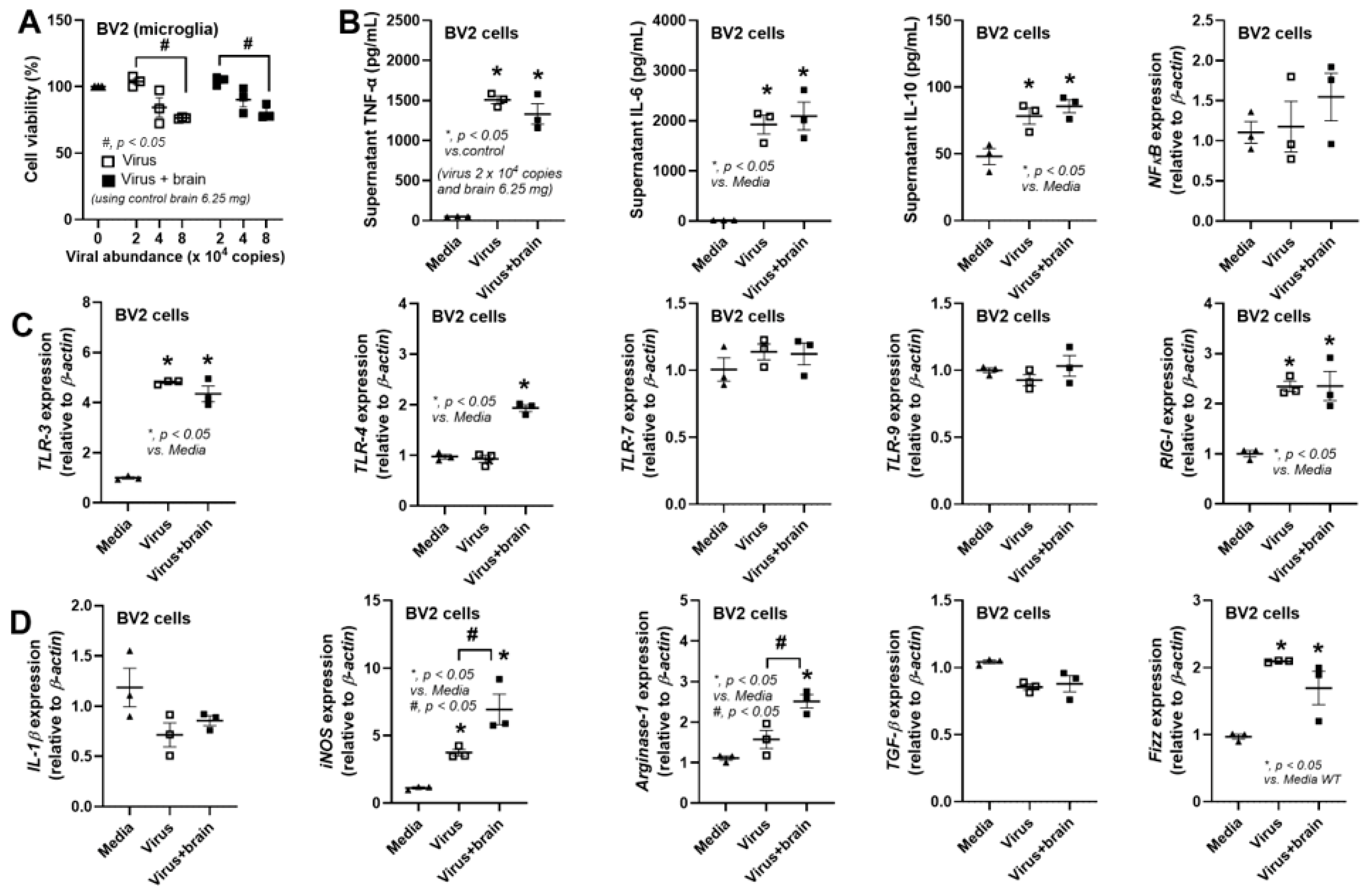

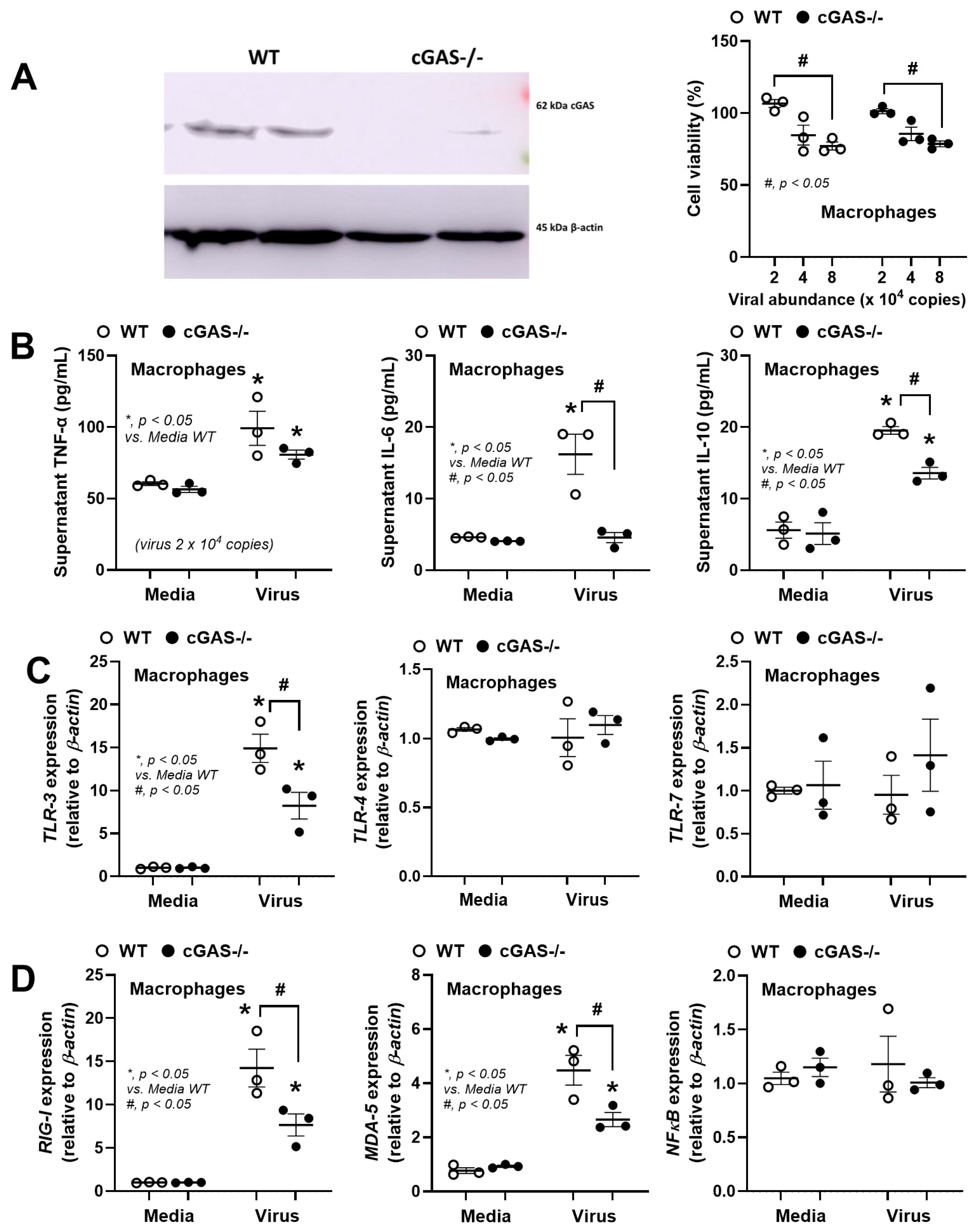

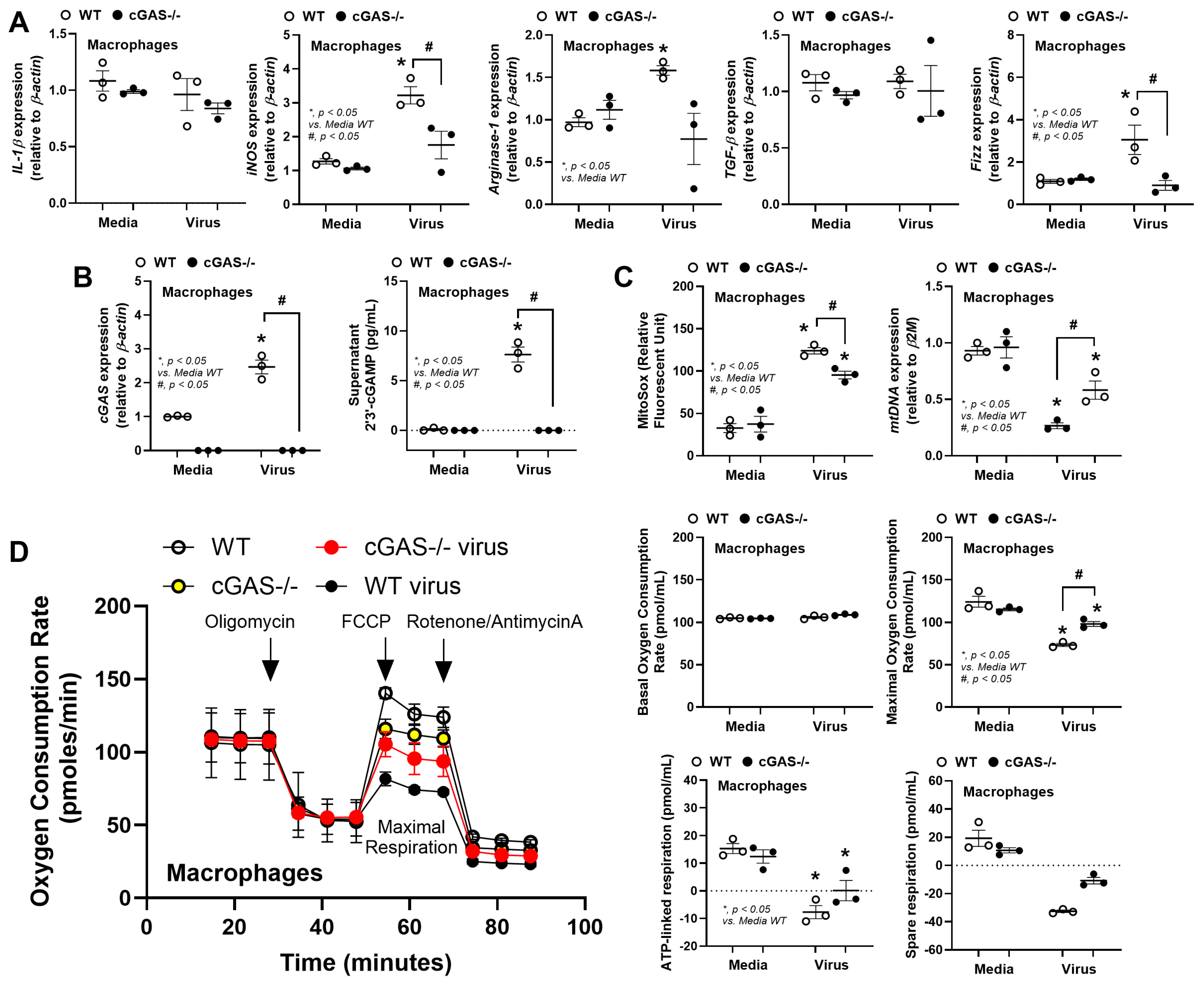

3.2. The Less Prominent Macrophage Responses in cGAS-/- than in WT Cells Implied Rabies-Induced Mitochondrial Damage

4. Discussion

4.1. Less Severe Inflammation in Rabies-Infected cGAS-/- Mice: Roles of Rabies-Induced Mitochondrial Injury

4.2. Stress-Induced Dysbiosis, an Interesting Gut–Brain Axis in Rabies

4.3. Clinical Aspects of the Study

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| TLR | Toll-like receptors |

| RIG-I | Retinoic acid-inducible gene I |

| cGAS | Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase |

| RNP | Ribonucleoprotein |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| i.m. | Intramuscular |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| BMMs | Bone-marrow-derived macrophages |

| dsRNA | Double-stranded RNA |

References

- Shams, F.; Jokar, M.; Djalali, E.; Abdous, A.; Rahnama, M.; Rahmanian, V.; Kanankege, K.S.T.; Seuberlich, T. Incidence and prevalence of rabies virus infections in tested humans and animals in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. One Health 2025, 20, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattiyakumbura, T.; Muthugala, R. Human Rabies: Laboratory Diagnosis, Management and Nanomedicine. Curr. Treat. Options Infect. Dis. 2024, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, J.; Song, Y.; Liu, X.; Qian, M.; Huang, P.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, H. Regulation of innate immune responses by rabies virus. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2022, 5, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conzelmann, K.-K. Activation and evasion of innate immune response by rhabdoviruses. In Biology and Pathogenesis of Rhabdo-and Filoviruses; World Scientific: Singapore, 2015; pp. 353–385. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Wang, J.; Huang, C.; Zhao, J.; Fu, Z.F.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, M. Interleukin-1β suppresses rabies virus infection by activating cGAS-STING pathway and compromising the blood-brain barrier integrity in mice. Vet. Microbiol. 2023, 280, 109708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedel, C.; Hennrich, A.A.; Conzelmann, K.K. Components and Architecture of the Rhabdovirus Ribonucleoprotein Complex. Viruses 2020, 12, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiflu, A.B. The Immune Escape Strategy of Rabies Virus and Its Pathogenicity Mechanisms. Viruses 2024, 16, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Fang, A.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Sui, B.; Zhao, J.; Fu, Z.F.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, L. Lyssavirus M protein degrades neuronal microtubules by reprogramming mitochondrial metabolism. mBio 2024, 15, e0288023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamichi, K.; Saiki, M.; Sawada, M.; Takayama-Ito, M.; Yamamuro, Y.; Morimoto, K.; Kurane, I. Rabies virus-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-kappaB signaling pathways regulates expression of CXC and CC chemokine ligands in microglia. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 11801–11812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, H.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Luo, J.; Kuang, Y.; Lv, Z.; Fan, R.; Zhang, B.; Luo, Y.; et al. Rabies Virus-Induced Autophagy Is Dependent on Viral Load in BV2 Cells. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 595678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, N.B.; Power, C.; Lynch, W.P.; Ewalt, L.C.; Lodmell, D.L. Rabies viruses infect primary cultures of murine, feline, and human microglia and astrocytes. Arch. Virol. 1997, 142, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltl, I.; Kalinke, U. Beneficial and detrimental functions of microglia during viral encephalitis. Trends Neurosci. 2022, 45, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louloudes-Lázaro, A.; Nogales-Altozano, P.; Rojas, J.M.; Veloz, J.; Carlón, A.B.; Van Rijn, P.A.; Martín, V.; Fernández-Sesma, A.; Sevilla, N. Double-stranded RNA orbivirus disrupts the DNA-sensing cGAS-sting axis to prevent type I IFN induction. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, G.; Ma, Z.; Damania, B. cGAS and STING: At the intersection of DNA and RNA virus-sensing networks. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammouni, W.; Wood, H.; Saleh, A.; Appolinario, C.M.; Fernyhough, P.; Jackson, A.C. Rabies virus phosphoprotein interacts with mitochondrial Complex I and induces mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. J. Neurovirol 2015, 21, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatel-Chaix, L.; Cortese, M.; Romero-Brey, I.; Bender, S.; Neufeldt, C.J.; Fischl, W.; Scaturro, P.; Schieber, N.; Schwab, Y.; Fischer, B.; et al. Dengue Virus Perturbs Mitochondrial Morphodynamics to Dampen Innate Immune Responses. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Varga, R.D.; Yang, J. The Impacts of Dengue Virus Infection on Mitochondrial Functions and Dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, N.; Fitzgerald, K.A. Recognition of cytosolic DNA by cGAS and other STING-dependent sensors. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 44, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paludan, S.R.; Reinert, L.S.; Hornung, V. DNA-stimulated cell death: Implications for host defence, inflammatory diseases and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The Gut-Brain Axis: Influence of Microbiota on Mood and Mental Health. Integr. Med. 2018, 17, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, L.; Gao, M.; Wen, S.; Wang, F.; Shangguan, H.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, R.; Ge, J. Effects of Catecholamine Stress Hormones Norepinephrine and Epinephrine on Growth, Antimicrobial Susceptibility, Biofilm Formation, and Gene Expressions of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, C.G.; Russell, R.; Mishra, A.A.; Narayanan, S.; Ritchie, J.M.; Waldor, M.K.; Curtis, M.M.; Winter, S.E.; Weinshenker, D.; Sperandio, V. Bacterial Adrenergic Sensors Regulate Virulence of Enteric Pathogens in the Gut. mBio 2016, 7, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, P.M.; Aviles, H.; Lyte, M.; Sonnenfeld, G. Enhancement of in vitro growth of pathogenic bacteria by norepinephrine: Importance of inoculum density and role of transferrin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 5097–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancharoenthana, W.; Kamolratanakul, S.; Schultz, M.J.; Leelahavanichkul, A. The leaky gut and the gut microbiome in sepsis —Targets in research and treatment. Clin. Sci. 2023, 137, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokephaibulkit, K.; Huoi, C.; Tantawichien, T.; Mootsikapun, P.; Kosalaraksa, P.; Kiertiburanakul, S.; Ratanasuwan, W.; Vangelisti, M.; Laot, T.; Huang, Y.; et al. Noninferiority Study of Purified Vero Rabies Vaccine—Serum Free in 3-dose and 2-dose Preexposure Prophylaxis Regimens in Comparison With Licensed Rabies Vaccines. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 81, 654–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visitchanakun, P.; Tangtanatakul, P.; Trithiphen, O.; Soonthornchai, W.; Wongphoom, J.; Tachaboon, S.; Srisawat, N.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Plasma miR-370-3P as a Biomarker of Sepsis-Associated Encephalopathy, the Transcriptomic Profiling Analysis of Microrna-Arrays From Mouse Brains. Shock 2020, 54, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thim-Uam, A.; Makjaroen, J.; Issara-Amphorn, J.; Saisorn, W.; Wannigama, D.L.; Chancharoenthana, W.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Enhanced Bacteremia in Dextran Sulfate-Induced Colitis in Splenectomy Mice Correlates with Gut Dysbiosis and LPS Tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chancharoenthana, W.; Kamolratanakul, S.; Udompornpitak, K.; Wannigama, D.L.; Schultz, M.J.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Alcohol-induced gut permeability defect through dysbiosis and enterocytic mitochondrial interference causing pro-inflammatory macrophages in a dose dependent manner. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visitchanakun, P.; Panpetch, W.; Saisorn, W.; Chatthanathon, P.; Wannigama, D.L.; Thim-Uam, A.; Svasti, S.; Fucharoen, S.; Somboonna, N.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Increased susceptibility to dextran sulfate-induced mucositis of iron-overload β-thalassemia mice, another endogenous cause of septicemia in thalassemia. Clin. Sci. 2021, 135, 1467–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondee, T.; Pongpirul, K.; Wongsaroj, L.; Senaprom, S.; Wattanaphansak, S.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum dfa1 reduces obesity caused by a high carbohydrate diet by modulating inflammation and gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thim-Uam, A.; Chantawichitwong, P.; Phuengmaung, P.; Kaewduangduen, W.; Saisorn, W.; Kumpunya, S.; Pisitkun, T.; Pisitkun, P.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Accelerating and protective effects toward cancer growth in cGAS and FcgRIIb deficient mice, respectively, an impact of macrophage polarization. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 74, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, K.D.; Wang, Q.; Nute, M.G.; Tyshaieva, A.; Reeves, E.; Soriano, S.; Wu, Q.; Graeber, E.; Finzer, P.; Mendling, W.; et al. Emu: Species-level microbial community profiling of full-length 16S rRNA Oxford Nanopore sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiengrach, P.; Visitchanakun, P.; Finkelman, M.A.; Chancharoenthana, W.; Leelahavanichkul, A. More Prominent Inflammatory Response to Pachyman than to Whole-Glucan Particle and Oat-β-Glucans in Dextran Sulfate-Induced Mucositis Mice and Mouse Injection through Proinflammatory Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udompornpitak, K.; Charoensappakit, A.; Sae-Khow, K.; Bhunyakarnjanarat, T.; Dang, C.P.; Saisorn, W.; Visitchanakun, P.; Phuengmaung, P.; Palaga, T.; Ritprajak, P.; et al. Obesity Exacerbates Lupus Activity in Fc Gamma Receptor IIb Deficient Lupus Mice Partly through Saturated Fatty Acid-Induced Gut Barrier Defect and Systemic Inflammation. J. Innate Immun. 2023, 15, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunyakarnjanarat, T.; Prapunwatana, P.; Tiranathanagul, K.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Determination of the number of times for reuse of hemodialysis dialyzer through macrophage responses against dialyzer-eluted protein, a proposed method. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksamai, C.; Kaewduangduen, W.; Phuengmaung, P.; Sae-Khow, K.; Charoensappakit, A.; Udomkarnjananun, S.; Lotinun, S.; Kueanjinda, P.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase (cGAS) Deletion Promotes Less Prominent Inflammatory Macrophages and Sepsis Severity in Catheter-Induced Infection and LPS Injection Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suksawad, N.; Udompornpitak, K.; Thawinpipat, N.; Korwattanamongkol, P.; Visitchanakun, P.; Phuengmaung, P.; Saisorn, W.; Kueanjinda, P.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase (cGAS) Deletion Reduces Severity in Bilateral Nephrectomy Mice through Changes in Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Mitochondrial Respiration. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visitchanakun, P.; Kaewduangduen, W.; Chareonsappakit, A.; Susantitaphong, P.; Pisitkun, P.; Ritprajak, P.; Townamchai, N.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Interference on Cytosolic DNA Activation Attenuates Sepsis Severity: Experiments on Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase (cGAS) Deficient Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuengmaung, P.; Saisorn, W.; Boonmee, A.; Benjaskulluecha, S.; Amornphimoltham, P.; Thim-Uam, A.; Palaga, T.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Less severe tumor growth in mice in which mgmt is conditionally deleted using the LysM-Cre system, and the possible impacts of DNA methylation in tumor-associated macrophages. Int. Immunol. 2025, 37, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; He, F.; Bi, S.; Guo, H.; Zhang, B.; Wu, F.; Liang, J.; Yang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Ju, C.; et al. Genome-Wide Transcriptional Profiling Reveals Two Distinct Outcomes in Central Nervous System Infections of Rabies Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquette, C.; Van Dam, A.M.; Ceccaldi, P.E.; Weber, P.; Haour, F.; Tsiang, H. Induction of immunoreactive interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the brains of rabies virus infected rats. J. Neuroimmunol. 1996, 68, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Punder, K.; Pruimboom, L. Stress induces endotoxemia and low-grade inflammation by increasing barrier permeability. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerkins, C.; Hajjar, R.; Oliero, M.; Santos, M.M. Assessment of Gut Barrier Integrity in Mice Using Fluorescein-Isothiocyanate-Labeled Dextran. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, 189, e64710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cao, Y.; Tang, Q.; Liang, G. Role of the blood-brain barrier in rabies virus infection and protection. Protein Cell 2013, 4, 901–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Q.; He, W.Q.; Zhou, M.; Lu, H.; Fu, Z.F. Enhancement of blood-brain barrier permeability and reduction of tight junction protein expression are modulated by chemokines/cytokines induced by rabies virus infection. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4698–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, F.; Gotteland, M.; Gauthier, L.; Zazueta, A.; Pesoa, S.; Navarrete, P.; Balamurugan, R. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A Relevant Marker of Gut Dysbiosis in Obese Patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, J.; Civas, A.; Lama, Z.; Lagaudrière-Gesbert, C.; Blondel, D. Rabies Virus Infection Induces the Formation of Stress Granules Closely Connected to the Viral Factories. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells-Nobau, A.; Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Fernández-Real, J.M. Unlocking the mind-gut connection: Impact of human microbiome on cognition. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 1248–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolourani, S.; Brenner, M.; Wang, P. The interplay of DAMPs, TLR4, and proinflammatory cytokines in pulmonary fibrosis. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 99, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, L.; Savini, C.; Ghittoni, R.; Saidj, D.; Lamartine, J.; Hasan, U.A.; Accardi, R.; Tommasino, M. Downregulation of Toll-Like Receptor 9 Expression by Beta Human Papillomavirus 38 and Implications for Cell Cycle Control. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 11396–11405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alandijany, T.; Kammouni, W.; Roy Chowdhury, S.K.; Fernyhough, P.; Jackson, A.C. Mitochondrial dysfunction in rabies virus infection of neurons. J. Neurovirol. 2013, 19, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.C.; Kammouni, W.; Fernyhough, P. Role of oxidative stress in rabies virus infection. Adv. Virus Res. 2011, 79, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, H.; Pitossi, F.; Balschun, D.; Wagner, A.; del Rey, A.; Besedovsky, H.O. A neuromodulatory role of interleukin-1beta in the hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 7778–7783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystofova, J.; Pathipati, P.; Russ, J.; Sheldon, A.; Ferriero, D. The Arginase Pathway in Neonatal Brain Hypoxia-Ischemia. Dev. Neurosci. 2018, 40, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber, M.; Bette, M.; Preuss, M.A.; Pulmanausahakul, R.; Rehnelt, J.; Schnell, M.J.; Dietzschold, B.; Weihe, E. Overexpression of tumor necrosis factor alpha by a recombinant rabies virus attenuates replication in neurons and prevents lethal infection in mice. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 15405–15416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munder, M. Arginase: An emerging key player in the mammalian immune system. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 158, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, C.P.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Over-expression of miR-223 induces M2 macrophage through glycolysis alteration and attenuates LPS-induced sepsis mouse model, the cell-based therapy in sepsis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.S.; Faustmann, T.J.; Faustmann, P.M.; Corvace, F. Microglia as potential key regulators in viral-induced neuroinflammation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1426079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandl, S.; Reindl, M. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in Neuroinflammation: Current In Vitro Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Levine, S.J. Toll-like receptor, RIG-I-like receptors and the NLRP3 inflammasome: Key modulators of innate immune responses to double-stranded RNA viruses. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2011, 22, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, A.; Mantovani, A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: In vivo veritas. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.M.; Wilkerson, M.J.; Davis, R.D.; Wyatt, C.R.; Briggs, D.J. Detection of cellular immunity to rabies antigens in human vaccinees. J. Clin. Immunol. 2006, 26, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménager, P.; Roux, P.; Mégret, F.; Bourgeois, J.P.; Le Sourd, A.M.; Danckaert, A.; Lafage, M.; Préhaud, C.; Lafon, M. Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) plays a major role in the formation of rabies virus Negri Bodies. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, M.; Weber, F. RIG-I-like receptors and negative-strand RNA viruses: RLRly bird catches some worms. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2014, 25, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aouadi, W.; Najburg, V.; Legendre, R.; Varet, H.; Kergoat, L.; Tangy, F.; Larrous, F.; Komarova, A.V.; Bourhy, H. Comparative analysis of rabies pathogenic and vaccine strains detection by RIG-I-like receptors. Microbes Infect. 2024, 26, 105321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chi, Y.; Tao, X.; Yu, P.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Yang, N.; Liu, S.; Zhu, W. Rabies Virus Regulates Inflammatory Response in BV-2 Cells through Activation of Myd88 and NF-κB Signaling Pathways via TLR7. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embregts, C.W.E.; Wentzel, A.S.; den Dekker, A.T.; van Ijcken, W.F.; Stadhouders, R.; GeurtsvanKessel, C.H. Rabies virus uniquely reprograms the transcriptome of human monocyte-derived macrophages. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1013842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, B.; Gao, H.; He, C.; Hua, R.; Liang, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xin, S.; Xu, J. Vagus Nerve and Underlying Impact on the Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis in Behavior and Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 6213–6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, X.; Wu, J.; Bao, L.; Tan, Z.; Chen, C. Peripheral nerves directly mediate the transneuronal translocation of silver nanomaterials from the gut to central nervous system. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, J.A.; Barraviera, B.; Calvi, S.A.; Carvalho, N.R.; Peraçoli, M.T.S. Antibody and cytokine serum levels in patients subjected to anti-rabies prophylaxis with serum-vaccination. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2006, 12, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Appolinário, C.M.; Allendorf, S.D.; Peres, M.G.; Ribeiro, B.D.; Fonseca, C.R.; Vicente, A.F.; Antunes, J.M.; Megid, J. Profile of Cytokines and Chemokines Triggered by Wild-Type Strains of Rabies Virus in Mice. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, K.; Matsunaga, M.; Isowa, T.; Kimura, K.; Kasugai, K.; Yoneda, M.; Kaneko, H.; Ohira, H. Transient responses of inflammatory cytokines in acute stress. Biol. Psychol. 2009, 82, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotiby, A. Immunology of Stress: A Review Article. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panpetch, W.; Tumwasorn, S.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in feces exacerbate leaky gut in mice with low dose dextran sulfate solution, impacts of specific bacteria. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzatti, G.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Gibiino, G.; Binda, C.; Gasbarrini, A. Proteobacteria: A Common Factor in Human Diseases. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9351507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, C.; Guo, M.; Cui, X.; Jing, Z.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, W.; Qi, H.; Zhang, H.; et al. Bacteroides acidifaciens in the gut plays a protective role against CD95-mediated liver injury. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2027853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.F.; Tietjen, G.W.; Gingrich, S.; King, T.C. Bacteroides bacteremia. Ann. Surg. 1977, 186, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daca, A.; Jarzembowski, T. From the Friend to the Foe-Enterococcus faecalis Diverse Impact on the Human Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, E.J.; Lee, H.H.; Kim, M.; Kim, M.K. Evaluation of Enterococcal Probiotic Usage and Review of Potential Health Benefits, Safety, and Risk of Antibiotic-Resistant Strain Emergence. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiengrach, P.; Panpetch, W.; Chindamporn, A.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Macrophage depletion alters bacterial gut microbiota partly through fungal overgrowth in feces that worsens cecal ligation and puncture sepsis mice. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, R.O.; Bell, S.L.; MacDuff, D.A.; Kimmey, J.M.; Diner, E.J.; Olivas, J.; Vance, R.E.; Stallings, C.L.; Virgin, H.W.; Cox, J.S. The Cytosolic Sensor cGAS Detects Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA to Induce Type I Interferons and Activate Autophagy. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairullah, A.R.; Kurniawan, S.C.; Hasib, A.; Silaen, O.S.M.; Widodo, A.; Effendi, M.H.; Ramandinianto, S.C.; Moses, I.B.; Riwu, K.H.P.; Yanestria, S.M. Tracking lethal threat: In-depth review of rabies. Open Vet. J. 2023, 13, 1385–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jane Ling, M.Y.; Halim, A.; Ahmad, D.; Ramly, N.; Hassan, M.R.; Syed Abdul Rahim, S.S.; Saffree Jeffree, M.; Omar, A.; Hidrus, A. Rabies in Southeast Asia: A systematic review of its incidence, risk factors and mortality. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e066587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Espósito, J.; Nagiri, R.K.; Gan, L.; Sinha, S.C. Identification and development of cGAS inhibitors and their uses to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 2025, 22, e00536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Cao, A.; Luo, Q.; Chen, D.; Zhao, W.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Bu, X.; Quan, J. Development of cyclopeptide inhibitors of cGAS targeting protein-DNA interaction and phase separation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xiong, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, M.; Zhao, W.; Xu, Y. Discovery of novel cGAS inhibitors based on natural flavonoids. Bioorg Chem. 2023, 140, 106802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, S.; Saneto, R.; Falk, M.J.; Anselm, I.; Cohen, B.H.; Haas, R.; Medicine Society, T.M. A modern approach to the treatment of mitochondrial disease. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2009, 11, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel, S.B.; Frikha-Benayed, D.; Ruff, R.R.; Yildirim, G.; Dixit, M.; Korstanje, R.; Robinson, L.; Miller, R.A.; Harrison, D.E.; Strong, J.R.; et al. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction using methylene blue or mitoquinone to improve skeletal aging. Aging 2024, 16, 4948–4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avula, S.; Parikh, S.; Demarest, S.; Kurz, J.; Gropman, A. Treatment of mitochondrial disorders. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2014, 16, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodmell, D.L.; Ewalt, L.C. Pathogenesis of street rabies virus infections in resistant and susceptible strains of mice. J. Virol. 1985, 55, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanet, B.; Costescu Strachinaru, D.I.; Van Nieuwenhove, M.; Soentjens, P. Factors influencing the immune response after a single-dose 3-visit pre-exposure rabies intradermal vaccination schedule: A retrospective multivariate analysis. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 37, 101867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmento, L.; Tseggai, T.; Dhingra, V.; Fu, Z.F. Rabies virus-induced apoptosis involves caspase-dependent and caspase-independent pathways. Virus Res. 2006, 121, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Forward | Reverse | Amplicon Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rabies L protein (RABL) Gene ID: 1489857 | 5′-GAGAGCCGTCTCTTAGAGGA-3′ | 5′-GCGCGACACCTTCTTGTTAG-3′ | 470 |

| Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR-3) Gene ID: 142980 | 5′-GTCTTCTGCACGAACCTGACAG-3′ | 5′-TGGAGGTTCTCCAGTTGGACCC-3′ | 164 |

| Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) Gene ID: 21898 | 5′-GGCAGCAGGTGGAATTGTAT-3′ | 5′-AGGCCCCAGAGTTTTGTTCT-3′ | 198 |

| Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR-7) Gene ID: 170743 | 5′-GTGATGCTGTGTGGTTTGTCTGG-3′ | 5′-CCTTTGTGTGCTCCTGGACCTA-3′ | 100 |

| Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR-9) Gene ID: 81897 | 5′-GCTGTCAATGGCTCTCAGTTCC-3′ | 5′-CCTGCAACTGTGGTAGCTCACT-3′ | 115 |

| Retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) Gene ID: 230073 | 5′-CCACCTACATCCTCAGCTATATGA-3′ | 5′-TGGGCCCTTGTTGTTCTTCT-3′ | 86 |

| Melanoma differentiation-associated protein (MDA-5) Gene ID: 71586 | 5′-GCCTGGAACGTAGACGACAT-3′ | 5′-TGGTTGGGCCACTTCCATTT-3′ | 249 |

| Cyclic GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS) Gene ID: 214763 | 5′-ATGTGAAGATTTCGCTCCTAATGA-3′ | 5’-GAAATGACTCAGCGGATTTCCT-3’ | 145 |

| Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS); Gene ID: 18126 | 5′-ACCCACATCTGGCAGAATGAG-3′ | 5′-AGCCATGACCTTTCGCATTAG-3′ | 111 |

| Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) Gene ID: 16176 | 5′-GAAATGCCACCTTTTGACAGTG-3′ | 5′-TGGATGCTCTCATCAGGACAG-3′ | 116 |

| Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) Gene ID: 21926 | 5′-CCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTCTC-3′ | 5′-AGATCCATGCCGTTGGCCAG-3′ | 135 |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) Gene ID: 16193 | 5′-TACCACTTCACAAGTCGGAGGC-3′ | 5′-CTGCAAGTGCA TCA TCGTTGTTC-3′ | 116 |

| Interleukin-10 (IL-10) Gene ID: 16153 | 5′-GCTCTTACTGACTGGCATGAG-3′ | 5′-CGCAGCTCTAGGAGCATGTG-3′ | 105 |

| Arginase-1 (Arg-1) Gene ID: 11846 | 5′-CTTGGCTTGCTTCGGAACTC-3′ | 5′-GGAGAAGGCGTTTGCTTAGTT-3′ | 146 |

| Resistin-like molecule-α1 (FIZZ-1) Gene ID: 57262 | 5′-GCCAGGTCCTGGAACCTTTC-3′ | 5′-GGAGCAGGGAGATGCAGATGA-3′ | 102 |

| Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) Gene ID: 21813 | 5′-CAGAGCTGCGCTTGCAGAG-3′ | 5′-GTCAGCAGCCGGTTACCAAG-3′ | 106 |

| Nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) Gene ID: 18033 | 5′-CTTCCTCAGCCATGGTACCTCT-3′ | 5′-CAAGTCTTCATCAGCATCAAACTG-3′ | 167 |

| β-actin Gene ID: 11461 | 5′-CGGTTCCGATGCCCTGAGGCTCTT-3′ | 5′-CGTCACACTTCATGATGGAATTGA-3′ | 100 |

| Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) Gene ID: PV231059.1 | 5′-CGTACACCCTCTAACCTAGAGAAGG-3′ | 5′-GGTTTTAAGTCTTACGCAATTTCC-3′ | 70 |

| β2-microglobulin (β2M) Gene ID: NM_009735.3 | 5′-TTCTGGTGCTTGTCTCACTGA-3′ | 5′-CAGTATGTTCGGCTTCCCATTC-3′ | 104 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Areekul, P.; Bhunyakarnjanarat, T.; Suebnuson, S.; Somsri, K.; Trakultritrung, S.; Taveethavornsawat, K.; Tencomnao, T.; Boonyasuppayakorn, S.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Less Severe Inflammation in Cyclic GMP–AMP Synthase (cGAS)-Deficient Mice with Rabies, Impact of Mitochondrial Injury, and Gut–Brain Axis. Biology 2025, 14, 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111583

Areekul P, Bhunyakarnjanarat T, Suebnuson S, Somsri K, Trakultritrung S, Taveethavornsawat K, Tencomnao T, Boonyasuppayakorn S, Leelahavanichkul A. Less Severe Inflammation in Cyclic GMP–AMP Synthase (cGAS)-Deficient Mice with Rabies, Impact of Mitochondrial Injury, and Gut–Brain Axis. Biology. 2025; 14(11):1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111583

Chicago/Turabian StyleAreekul, Pannatat, Thansita Bhunyakarnjanarat, Sakolwan Suebnuson, Kollawat Somsri, Somchanok Trakultritrung, Kris Taveethavornsawat, Tewin Tencomnao, Siwaporn Boonyasuppayakorn, and Asada Leelahavanichkul. 2025. "Less Severe Inflammation in Cyclic GMP–AMP Synthase (cGAS)-Deficient Mice with Rabies, Impact of Mitochondrial Injury, and Gut–Brain Axis" Biology 14, no. 11: 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111583

APA StyleAreekul, P., Bhunyakarnjanarat, T., Suebnuson, S., Somsri, K., Trakultritrung, S., Taveethavornsawat, K., Tencomnao, T., Boonyasuppayakorn, S., & Leelahavanichkul, A. (2025). Less Severe Inflammation in Cyclic GMP–AMP Synthase (cGAS)-Deficient Mice with Rabies, Impact of Mitochondrial Injury, and Gut–Brain Axis. Biology, 14(11), 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111583