Research on the Mechanism of Hypoxia Tolerance of a Hybrid Fish Using Transcriptomics and Metabolomics

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Fish and Feeding Protocol

2.2. Hypoxia Treatment

2.3. Sample Collection and Processing

2.4. Gill Histology and Data Analysis

2.5. Blood Sample Analysis

2.6. Transcriptome Sequencing

2.7. Extraction and Identification of Metabolites

2.8. Association Analysis of Metabolome and Transcriptome

2.9. Validation of Candidate Genes Using qRT-PCR

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Verification of Hypoxic Tolerance Ability of BTB

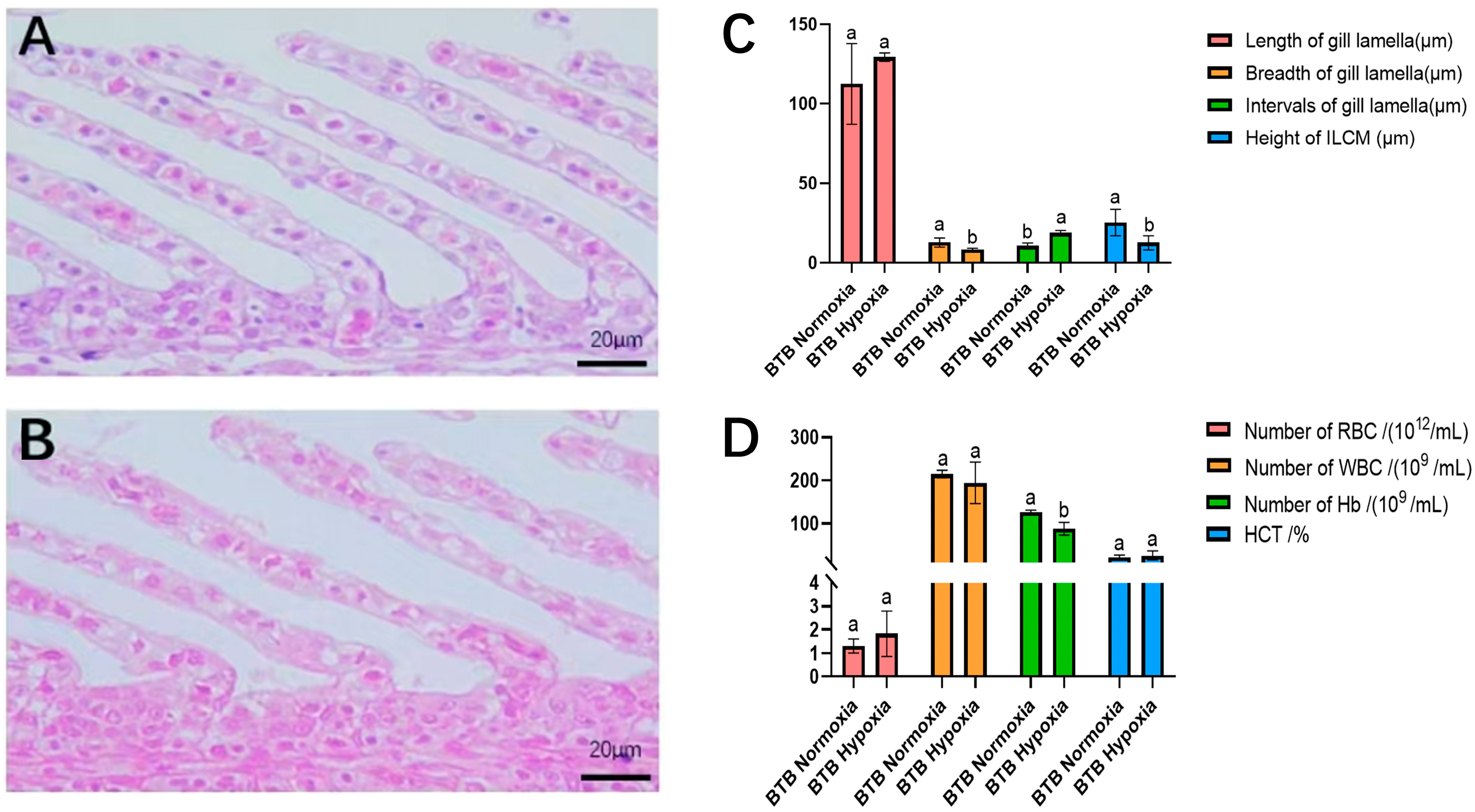

3.2. Gill Morphological Change Under Hypoxic Conditions

3.3. Blood Analysis

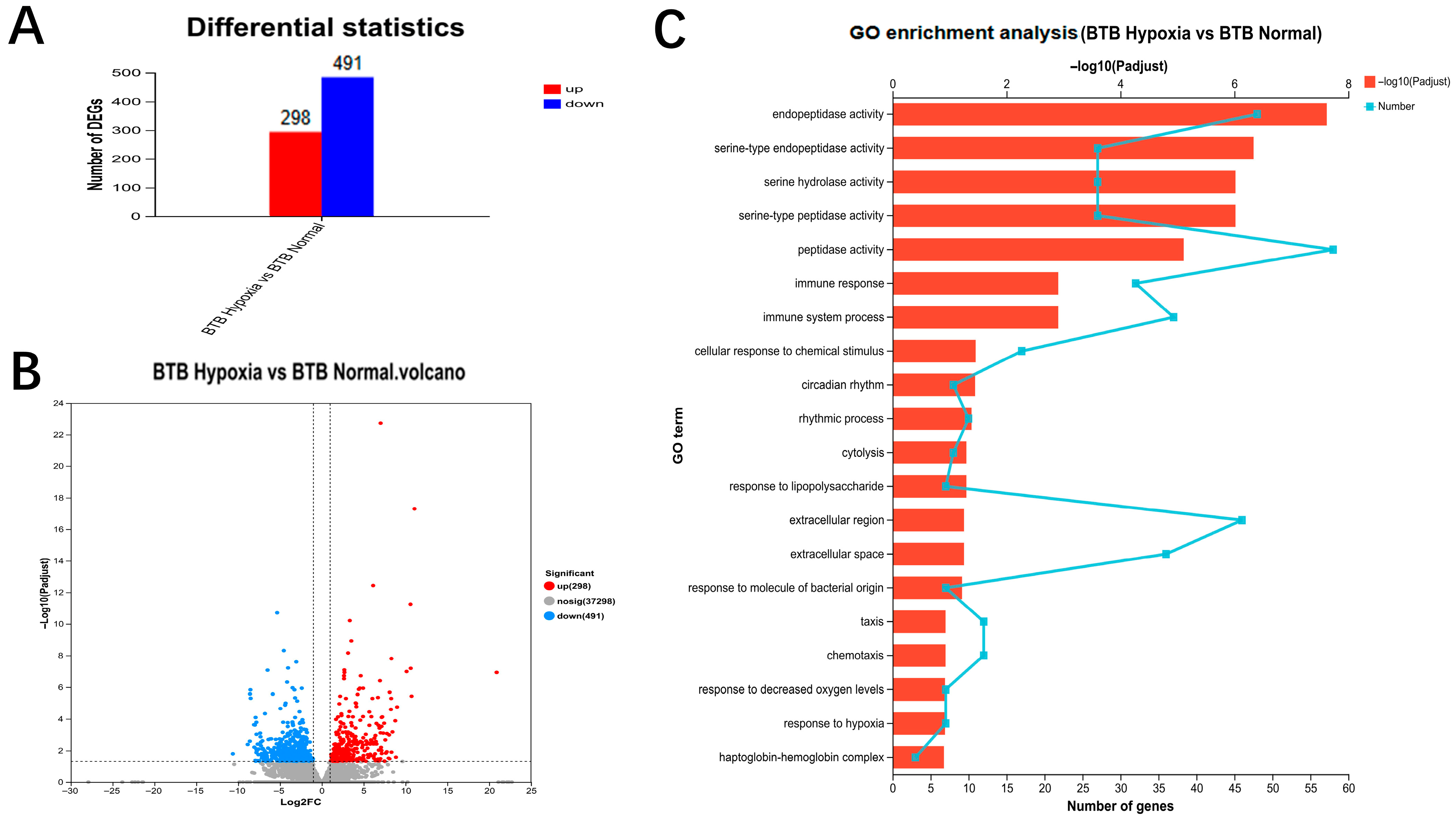

3.4. Transcriptome Sequencing, DEGs Identification, and Functional Enrichment

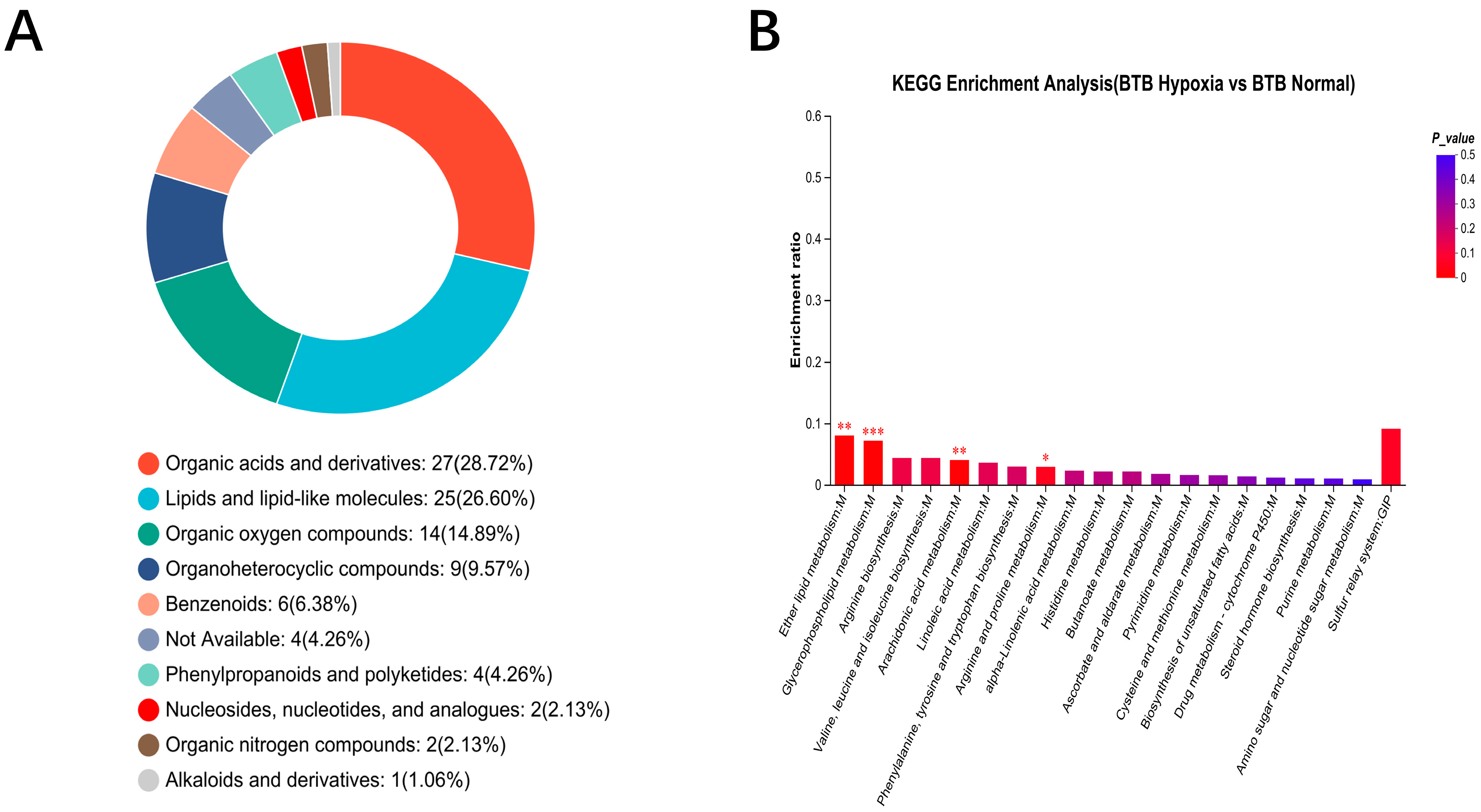

3.5. Metabolomic Analysis

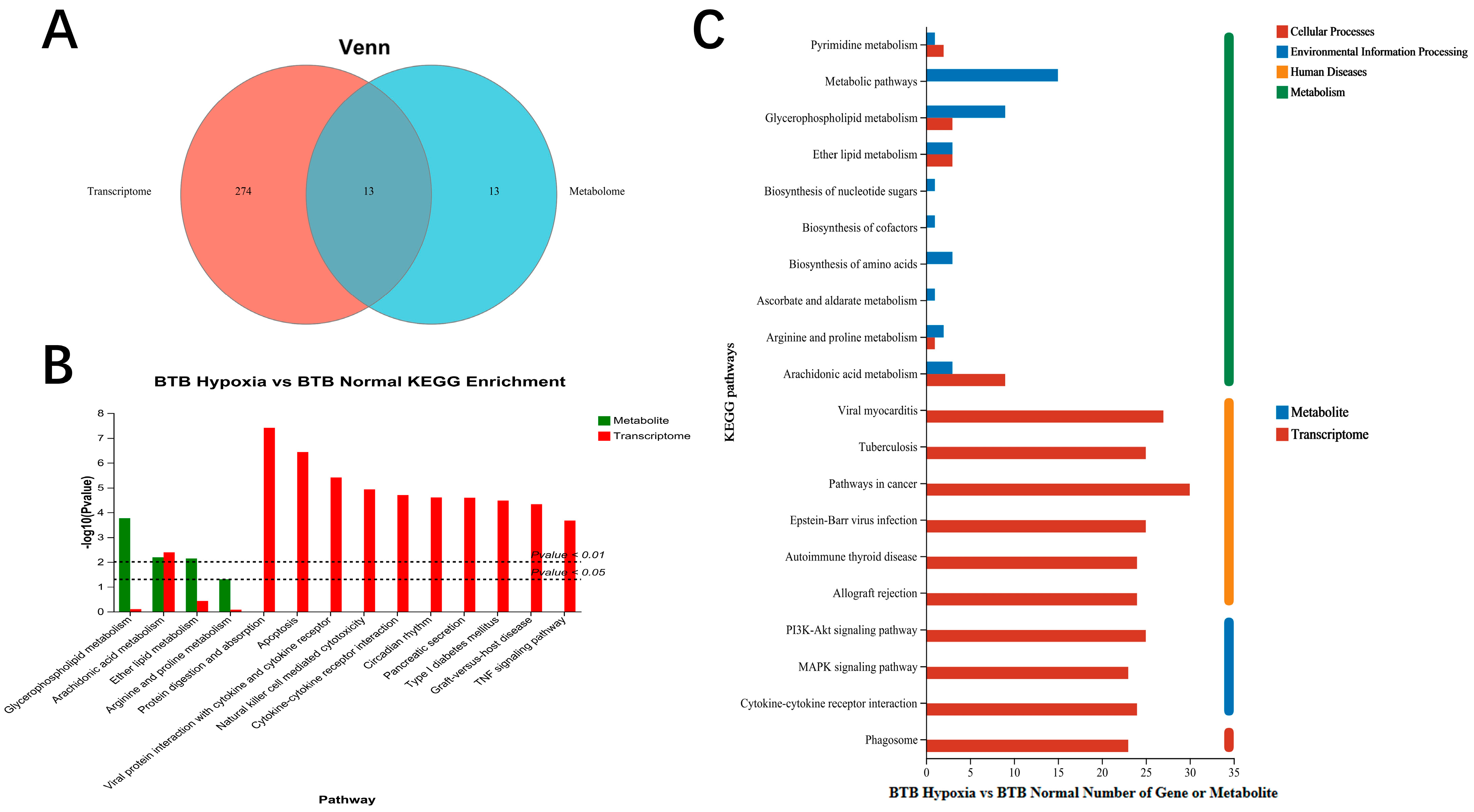

3.6. Association Analysis of Transcriptome and Metabolome

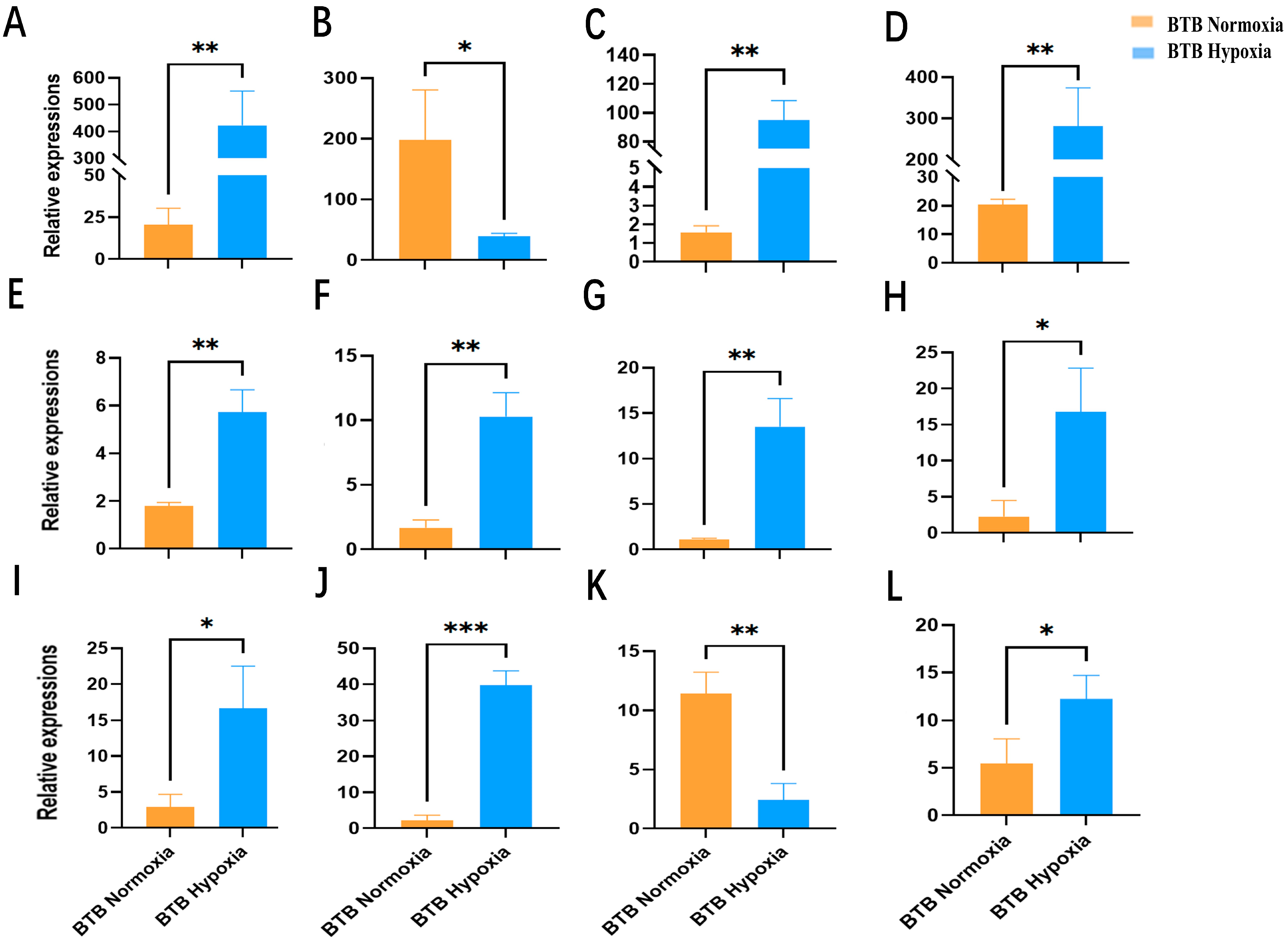

3.7. Validation of Candidate Genes Using qRT-PCR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ding, J.; Liu, C.; Luo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Wu, X.; Shen, W.; Zhu, J. Transcriptome and physiology analysis identify key metabolic changes in the liver of the large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) in response to acute hypoxia. Environ. Saf. 2020, 189, 109957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffin, M.R.S.; Courtenay, S.C.; Pater, C.C.; van den Heuvel, M.R. An empirical model using dissolved oxygen as an indicator for eutrophication at a regional scale. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, J.; Zhong, C.Y.; Bao, J.W.; Liang, M.; Liang, C.; Li, H.X.; He, J.; Xu, P. The effects of temperature and dissolved oxygen on the growth, survival and oxidative capacity of newly hatched hybrid yellow catfish larvae (Tachysurus fulvidraco♀ × Pseudobagrus vachellii♂). J. Therm. Biol. 2019, 86, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, K.; Qiang, J.; He, J.; Tao, Y.-F.; Bao, J.-W.; Zhu, J.-H.; Xu, P. Hypoxia-induced miR-92a regulates p53 signaling pathway and apoptosis by targeting calcium-sensing receptor in genetically improved farmed tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitburg, D.; Levin, L.A.; Oschlies, A.; Grégoire, M.; Chavez, F.P.; Conley, D.J.; Garçon, V.; Gilbert, D.; Gutiérrez, D.; Isensee, K.; et al. Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 2018, 359, 7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Tawwab, M.; Monier, M.N.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Faggio, C. Fish response to hypoxia stress: Growth, physiological, and immunological biomarkers. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 45, 997–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.L.; Zhao, L.L.; Wu, H.; Liu, Q.; Liao, L.; Luo, J.; Lian, W.Q.; Cui, C.; Jin, L.; Ma, J.D.; et al. Acute hypoxia changes the mode of glucose and lipid utilization in the liver of the largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 135157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yan, T.; Wu, H.; Xiao, Q.; Fu, H.M.; Luo, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, L.L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.Y.; et al. Acute hypoxic stress: Effect on blood parameters, antioxidant enzymes, and expression of HIF-1alpha and GLUT-1 genes in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 67, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzaneva, V.; Vadeboncoeur, C.; Ting, J.; Perry, S.F. Effects of hypoxia-induced gill remodelling on the innervation and distribution of ionocytes in the gill of goldfish, Carassius auratus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2013, 522, 118–130. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.-D.; Wen, H.-L.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wu, P.; Zhao, J.; Kuang, S.-Y.; Tang, L.; Tang, W.-N.; Zhang, Y.-A.; et al. Enhanced muscle nutrient content and flesh quality, resulting from tryptophan, is associated with anti-oxidative damage referred to the Nrf2 and TOR signalling factors in young grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella): Avoid tryptophan deficiency or excess. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, T.; Pal, A.K.; Mishal, P.; Sahu, N.P.; Dasgupta, S. Physiological and Molecular Responses of a Bottom Dwelling Carp, Cirrhinus mrigala to Short-Term Environmental Hypoxia. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2018, 18, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, X.; Qi, C.; Li, E.; Du, Z.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L. Metabolic response of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) to acute and chronic hypoxia stress. Aquaculture 2018, 495, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Xia, M.; Chao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, R. Identification, molecular evolution of toll-like receptors in a Tibetan schizothoracine fish (Gymnocypris eckloni) and their expression profiles in response to acute hypoxia. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 68, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Li, W.; Qin, Q.; Dai, H.; Han, F.; Xiao, J.; Gao, X.; Cui, J.; Wu, C.; Yan, X.; et al. The subgenomes show asymmetric expression of alleles in hybrid lineages of Megalobrama amblycephala × Culter alburnus. Genome Res. 2019, 29, 1805–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Kang, X.; Xie, L.; Qin, Q.; He, Z.; Hu, F.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, R.; Wang, J.; Luo, K.; et al. The fertility of the hybrid lineage derived from female Megalobrama amblycephala× male Culter alburnus. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 151, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Tang, C.; Tao, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, Q.; Luo, K.; Wu, C.; Hu, F.; et al. The Research Advances in Distant Hybridization and Gynogenesis in Fish. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 17, e12972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Du, X.; Yang, C.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Q. Integrated application of transcriptomics and metabolomics provides insights into unsynchronized growth in pearl oyster Pinctada fucata martensii. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 666, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiong, X.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, C.; Du, X. Integrated application of transcriptomics and metabolomics provides insights into the larval metamorphosis of pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata martensii). Aquaculture 2021, 532, 736067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Hu, X.; Sun, B.; Bo, Y.; Wu, K.; Xiao, L.; Gong, C. A transcriptome analysis focusing on inflammation-related genes of grass carp intestines following infection with Aeromonas hydrophila. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saetan, W.; Tian, C.; Yu, J.; Lin, X.; He, F.; Huang, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Gill Tissue in Response to Hypoxia in Silver Sillago (Sillago sihama). Animals 2020, 10, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.L.; Lin, H.R.; Xia, J.H. Differential Gene Expression Profiles and Alternative Isoform Regulations in Gill of Nile Tilapia in Response to Acute Hypoxia. Mar. Biotechnol. 2017, 19, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.-L.; Mao, M.-G.; Lü, H.-Q.; Wen, S.-H.; Sun, M.-L.; Liu, R.-t.; Jiang, Z.-Q. Digital gene expression analysis of Takifugu rubripes brain after acute hypoxia exposure using next-generation sequencing. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D 2017, 24, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, B.; Jin, S.-R.; Chen, Z.-Z.; Gao, J.-Z. Physiological responses to cold stress in the gills of discus fish (Symphysodon aequifasciatus) revealed by conventional biochemical assays and GC-TOF-MS metabolomics. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 640–641, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, X.; Wang, T.; Yin, S. Integrated application of multi-omics provides insights into cold stress responses in pufferfish Takifugu fasciatus. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.-L.; Qiang, J.; Tao, Y.-F.; Bao, J.-W.; Zhu, H.-J.; Li, L.-G.; Xu, P. Multi-omics analysis reveals the glycolipid metabolism response mechanism in the liver of genetically improved farmed Tilapia (GIFT, Oreochromis niloticus) under hypoxia stress. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J.R. The respiratory metabolism and swimming performance of young sockeye salmon. J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1964, 21, 1183–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.M.; Calduch-Giner, J.À.; Pereira, G.V.; Gonçalves, A.T.; Dias, J.; Johansen, J.; Silva, T.; Naya-Català, F.; Piazzon, C.; Sitjà-Bobadilla, A.; et al. Sustainable Fish Meal-Free Diets for Gilthead Sea Bream (Sparus aurata): Integrated Biomarker Response to Assess the Effects on Growth Performance, Lipid Metabolism, Antioxidant Defense and Immunological Status. Animals 2024, 14, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batıoğlu, F.; Yanık, Ö.; Ellialtıoğlu, P.A.; Demirel, S.; Şahlı, E.; Özmert, E. A comparative study of choroidal structural features in eyes with central macular atrophy related to Stargardt disease and non—Exudative age—Related macular degeneration. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 72 (Suppl. S5), S887–S892. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.-B.; Zheng, G.-D.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Zhou, S.; Zou, S.-M. Hypoxia tolerance in a selectively bred F4 population of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) under hypoxic stress. Aquaculture 2020, 518, 734484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qiu, J.; Yang, C.; Liao, Y.; He, M.; Mkuye, R.; Li, J.; Deng, Y.; Du, X. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis sheds new light on adaptation of Pinctada fucata martensii to short-term hypoxic stress. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 187, 114534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, J.; Bao, W.J.; Tao, F.Y.; He, J.; Li, X.H.; Xu, P.; Sun, L.Y. The expression profiles of miRNA–mRNA of early response in genetically improved farmed tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) liver by acute heat stress. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Lv, W.; Wang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Wang, C.; Sun, N.; Fang, C.; Irwin, D.M.; Gan, X.; He, S.; et al. Multi-omics Investigation of Freeze Tolerance in the Amur Sleeper, an Aquatic Ectothermic Vertebrate. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2023, 40, msad040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zhou, Y.-l.; Guo, X.-f.; Wei, W.-y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Z.-w.; Gui, J.-f. Comparative transcriptomes and metabolomes reveal different tolerance mechanisms to cold stress in two different catfish species. Aquaculture 2022, 560, 738543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untergasser, A.; Cutcutache, I.; Koressaar, T.; Ye, J.; Faircloth, B.C.; Remm, M.; Rozen, S.G. Primer3—New capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, J.; Tao, Y.-F.; He, J.; Xu, P.; Bao, J.-W.; Sun, Y.-L. miR-122 promotes hepatic antioxidant defense of genetically improved farmed tilapia (GIFT, Oreochromis niloticus) exposed to cadmium by directly targeting a metallothionein gene. Aquat. Toxicol. 2017, 182, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Zhu, C.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Tao, M.; Hu, L.; Rao, W.; Li, S.; et al. Mechanism of hypoxia tolerance improvement in hybrid fish Hefang bream. Aquaculture 2025, 599, 742199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matey, V.; Richards, J.G.; Wang, Y.; Wood, C.M.; Rogers, J.; Davies, R.; Murray, B.W.; Chen, X.Q.; Du, J.; Brauner, C.J. The effect of hypoxia on gill morphology and ionoregulatory status in the Lake Qinghai scaleless carp, Gymnocypris przewalskii. J. Exp. Biol. 2008, 211, 1063–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.-F.; Qiang, J.; Dagoudo, M.; Zhu, H.-J.; Bao, J.-W.; Ma, J.-L.; Li, M.-X.; Xu, P. Transcriptome profiling reveals differential expression of immune-related genes in gills of hybrid yellow catfish (Tachysurus fulvidraco ♀ × Pseudobagrus vachellii ♂) under hypoxic stress: Potential NLR-mediated immune response. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021, 119, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollid, J.; De Angelis, P.; Gundersen, K.; Nilsson, G.r.E. Hypoxia induces adaptive and reversible gross morphological changes in crucian carp gills. J. Exp. Biol. 2003, 206, 3667–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; You, F.; Wen, A.; Ma, D.; Zhang, P. Physiological and morphological effects of severe hypoxia, hypoxia and hyperoxia in juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus L.). Aquac. Res. 2016, 47, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xie, T.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Liu, Z.; Jia, Y. Hypoxia tolerance and physiological coping strategies in fat greenling (Hexagrammos otakii). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 51, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, C.; Lv, W.; Li, L.; He, S. Hb adaptation to hypoxia in high-altitude fishes: Fresh evidence from schizothoracinae fishes in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamenter, M.E.; Hall, J.E.; Tanabe, Y.; Simonson, T.S. Cross-Species Insights Into Genomic Adaptations to Hypoxia. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 00743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townley, I.K.; Karchner, S.I.; Skripnikova, E.; Wiese, T.E.; Hahn, M.E.; Rees, B.B. Sequence and functional characterization of hypoxia-inducible factors, HIF1α, HIF2αa, and HIF3α, from the estuarine fish, Fundulus heteroclitus. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2017, 312, R412–R425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandic, M.; Joyce, W.; Perry, S.F. The evolutionary and physiological significance of the Hif pathway in teleost fishes. J. Exp. Biol. 2021, 224, 231936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-X.; Yi, S.-K.; Wang, W.-F.; He, Y.; Huang, Y.; Gao, Z.-X.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.-M.; Wang, H.-L. Transcriptome comparison reveals insights into muscle response to hypoxia in blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). Gene 2017, 624, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Tan, H.; Liu, J.; Hu, J.; Cui, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Hu, F. Comparative analysis of testis transcriptomes associated with male infertility in triploid cyprinid fish. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2019, 31, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, C.I.; Suda, T. Regulation of reactive oxygen species in stem cells and cancer stem cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2011, 227, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yue, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Lv, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, Y. The PCK2-glycolysis axis assists three-dimensional-stiffness maintaining stem cell osteogenesis. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 18, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Thomas, P. Characterization of three IGFBP mRNAs in Atlantic croaker and their regulation during hypoxic stress: Potential mechanisms of their upregulation by hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 301, E637–E648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajimura, S.; Aida, K.; Duan, C. Understanding Hypoxia-Induced Gene Expression in Early Development: In Vitro and In Vivo Analysis of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-Regulated Zebra Fish Insulin-Like Growth Factor Binding Protein 1 Gene Expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2023, 26, 1142–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaerts, P.; Kamei, H.; Lu, L.; Jiao, S.; Li, Y.; Gyrup, C.; Laursen, L.S.; Oxvig, C.; Zhou, J.; Duan, C. Duplication and Diversification of the Hypoxia-Inducible IGFBP-1 Gene in Zebrafish. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Li, W.; Wu, B.; Chen, J.; Chen, X. Transcriptome analysis reveals new insights into immune response to hypoxia challenge of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 98, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvamme, B.O.; Gadan, K.; Finne-Fridell, F.; Niklasson, L.; Sundh, H.; Sundell, K.; Taranger, G.L.; Evensen, Ø. Modulation of innate immune responses in Atlantic salmon by chronic hypoxia-induced stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 34, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertwanakarn, T.; Khemthong, M.; Tattiyapong, P.; Surachetpong, W. The Modulation of Immune Responses in Tilapinevirus tilapiae-Infected Fish Cells through MAPK/ERK Signalling. Viruses 2023, 15, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Luo, W.; Yu, X.; Wang, J.; Feng, Y.; Tong, J. Cardiac Transcriptomics Reveals That MAPK Pathway Plays an Important Role in Hypoxia Tolerance in Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis). Animals 2020, 10, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Class | Adjusted p-Value | VIP | FC | Regulate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argininic acid | Carboxylic acids and derivatives | 0.0005 | 3.26 | 1.229 | up |

| S-Adenosylmethionine | S-Adenosylmethionine | 0.008 | 3.09 | 1.282 | up |

| 2-Hydroxydecanedioic acid | Hydroxy acids and derivatives | 0.001 | 3.05 | 0.82 | down |

| Lysylthreonine | Carboxylic acids and derivatives | 0.007 | 2.85 | 1.22 | up |

| Nopalinic acid | Carboxylic acids and derivatives | 0.009 | 2.75 | 1.202 | up |

| Glycerylphosphorylcholine | Glycerophospholipids | 0.004 | 2.67 | 1.126 | up |

| Meclizine | Benzene and substituted derivatives | 0.004 | 2.60 | 1.093 | up |

| APGPR Enterostatin | Benzene and substituted derivatives | 0.007 | 2.04 | 1.105 | up |

| Diphenyl disulfide | Benzene and substituted derivatives | 0.006 | 2.03 | 1.082 | up |

| N-a-Acetyl-L-arginine | Carboxylic acids and derivatives | 0.006 | 1.87 | 1.065 | up |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, H.; Hu, L.; Rao, W.; Yu, X.; Wen, M.; Tao, M.; Liu, S. Research on the Mechanism of Hypoxia Tolerance of a Hybrid Fish Using Transcriptomics and Metabolomics. Biology 2025, 14, 1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101462

Tang Y, Yang J, Zhu C, Zhang H, Hu L, Rao W, Yu X, Wen M, Tao M, Liu S. Research on the Mechanism of Hypoxia Tolerance of a Hybrid Fish Using Transcriptomics and Metabolomics. Biology. 2025; 14(10):1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101462

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Yuhua, Jiayi Yang, Chunchun Zhu, Hong Zhang, Li Hu, Wenting Rao, Xinxin Yu, Ming Wen, Min Tao, and Shaojun Liu. 2025. "Research on the Mechanism of Hypoxia Tolerance of a Hybrid Fish Using Transcriptomics and Metabolomics" Biology 14, no. 10: 1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101462

APA StyleTang, Y., Yang, J., Zhu, C., Zhang, H., Hu, L., Rao, W., Yu, X., Wen, M., Tao, M., & Liu, S. (2025). Research on the Mechanism of Hypoxia Tolerance of a Hybrid Fish Using Transcriptomics and Metabolomics. Biology, 14(10), 1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101462