Human Blastoid: A Next-Generation Model for Reproductive Medicine?

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

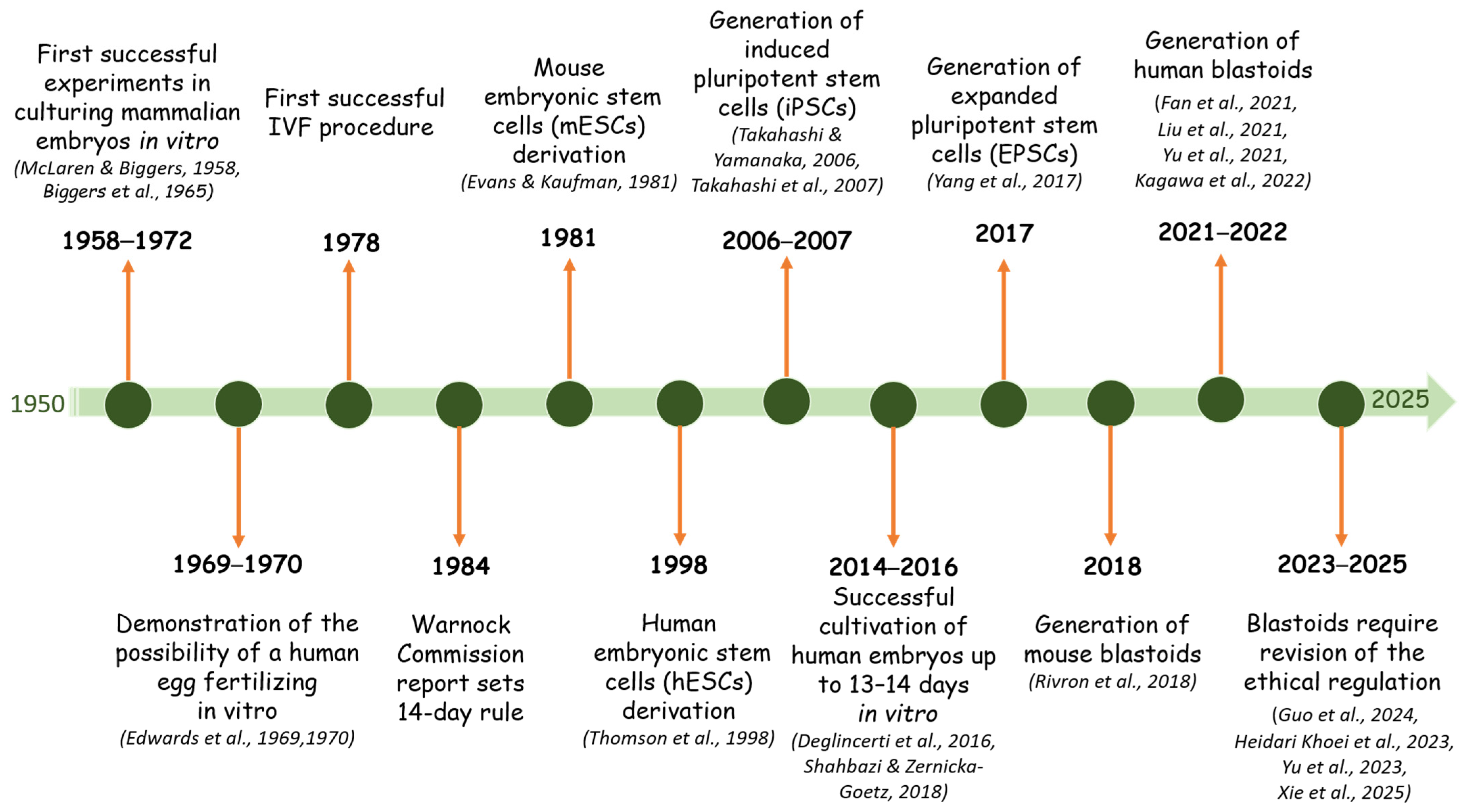

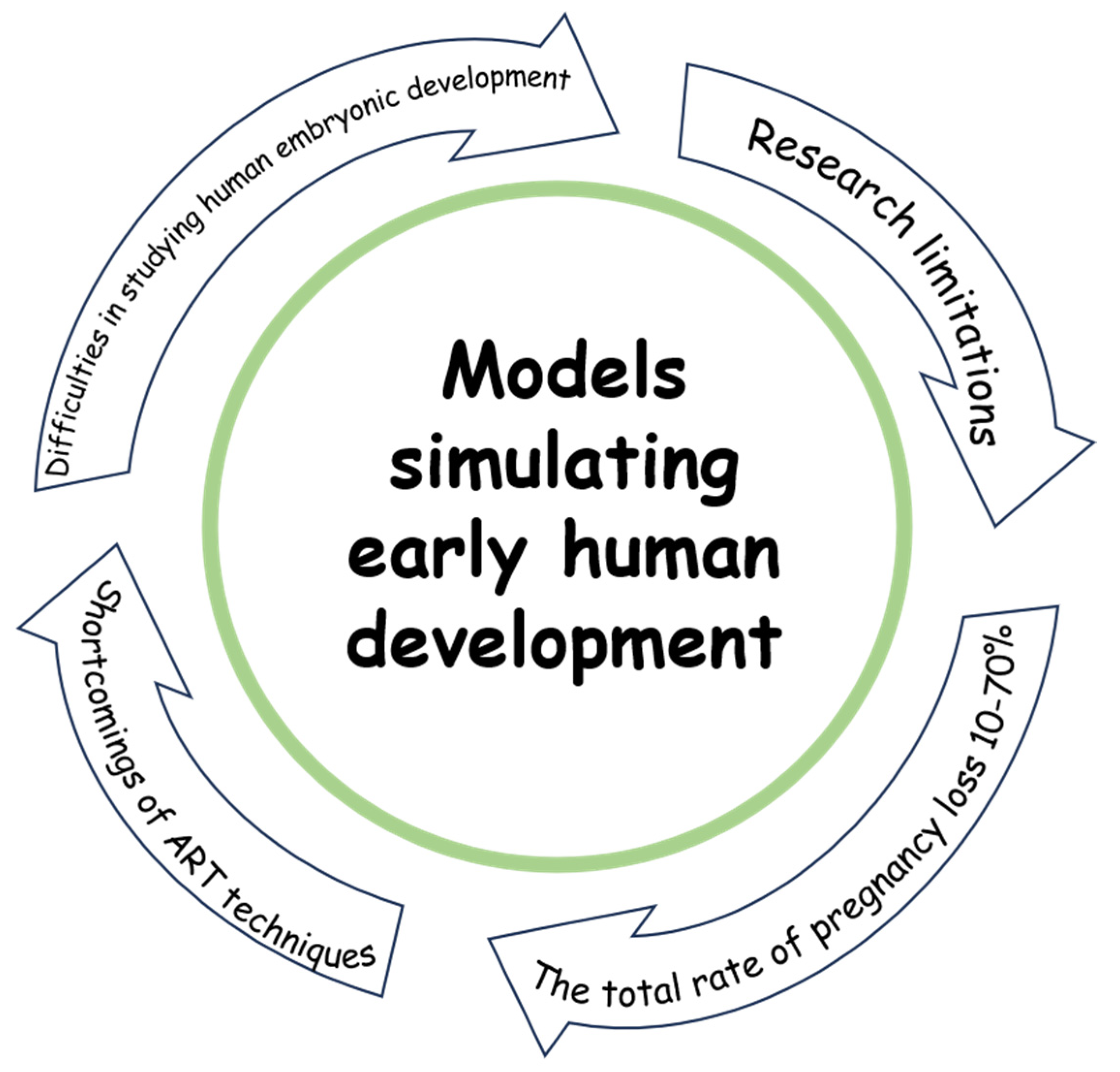

1. Introduction

2. Difficulties in Studying Human Embryonic Development

3. Blastocyst-Like Structures

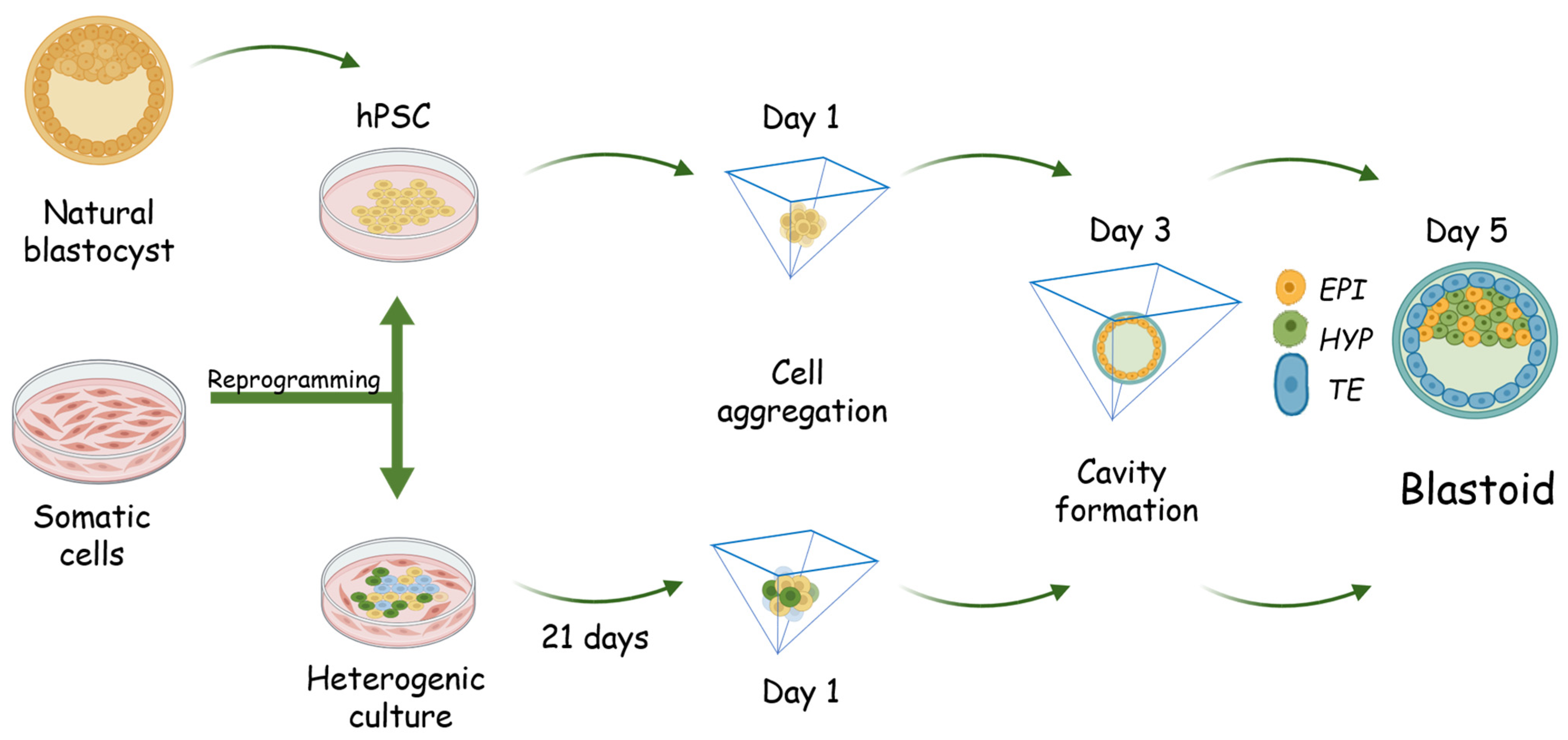

4. Generation of Human Blastoid

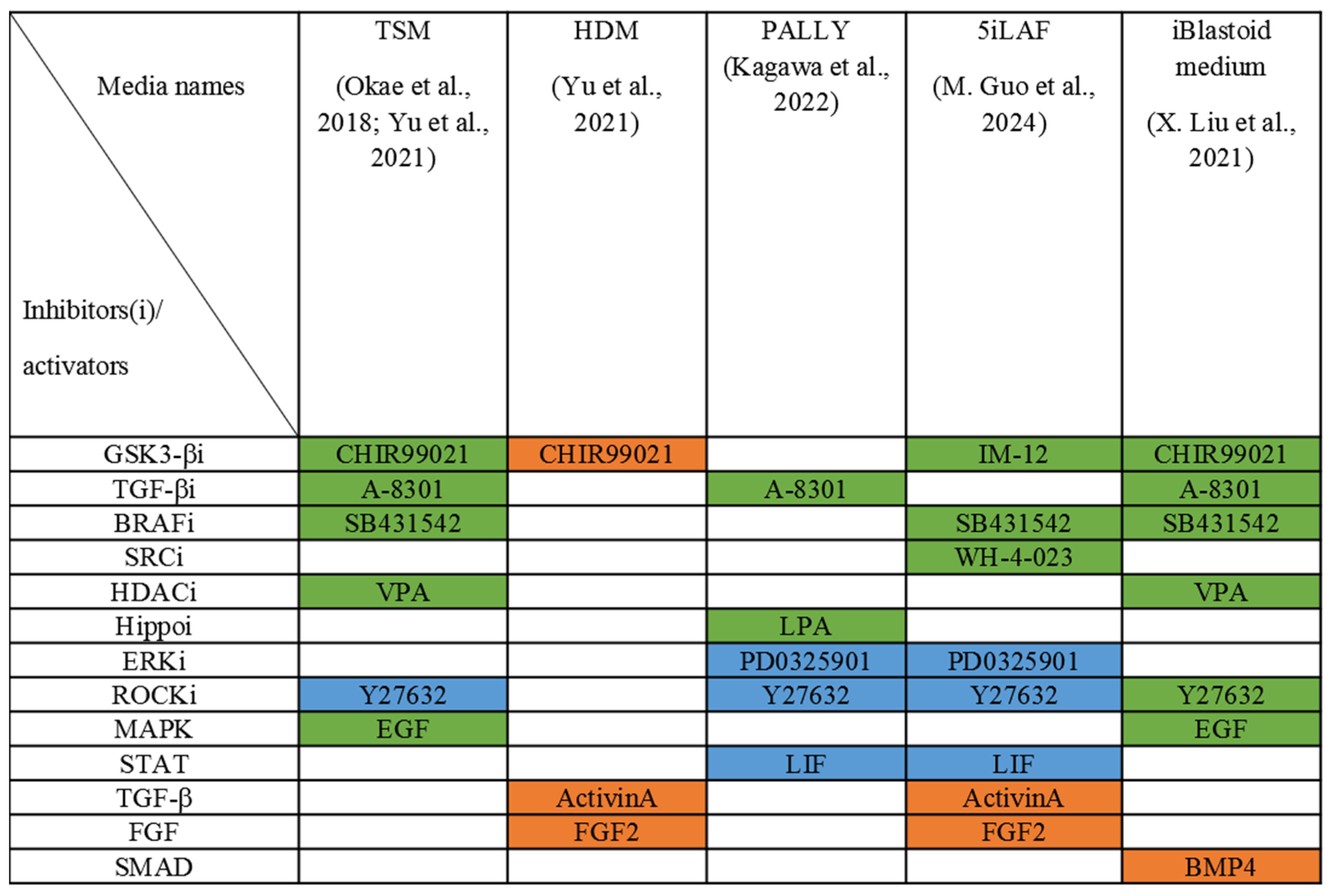

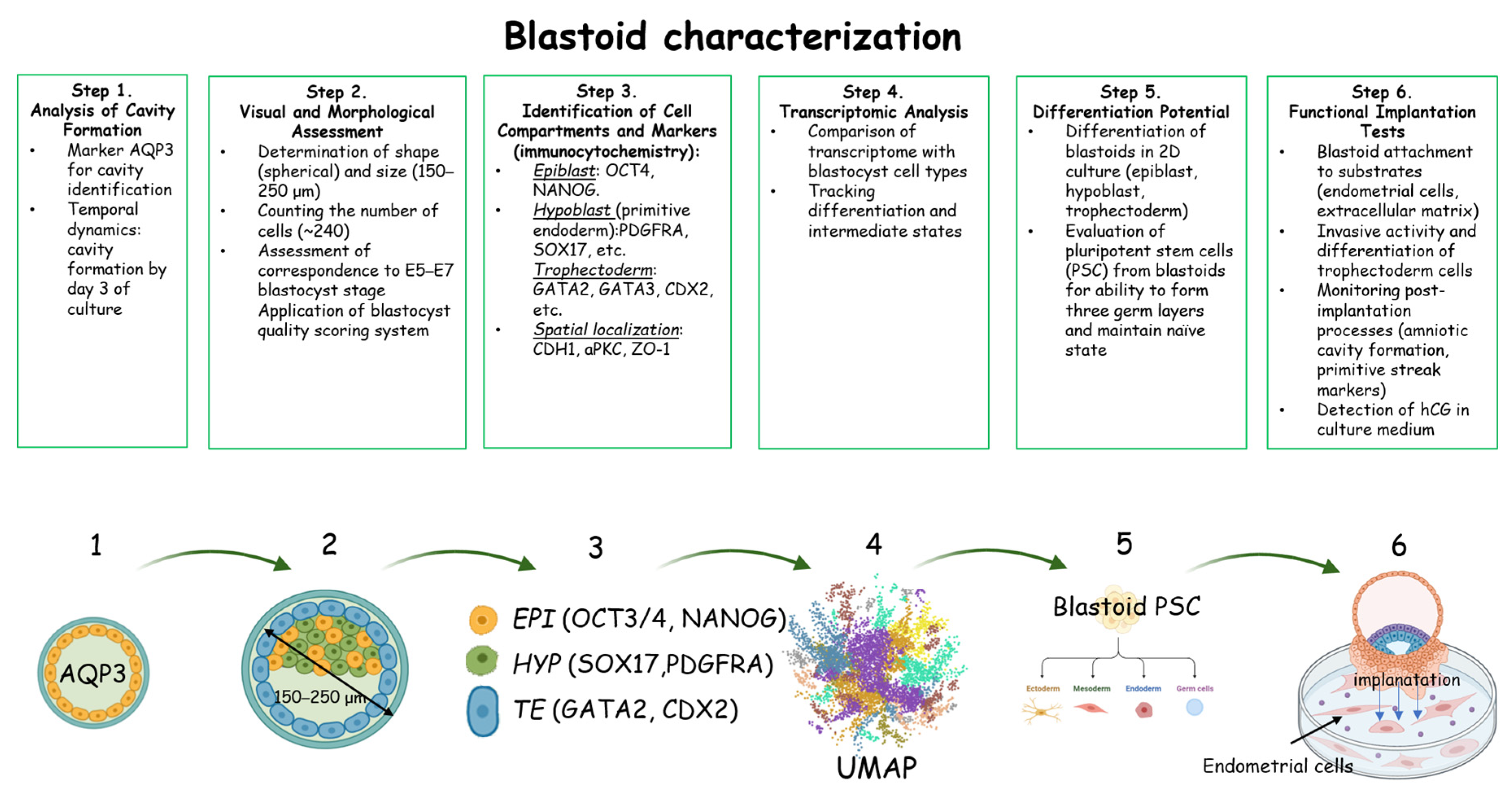

5. Characterization of the Forming Blastoids

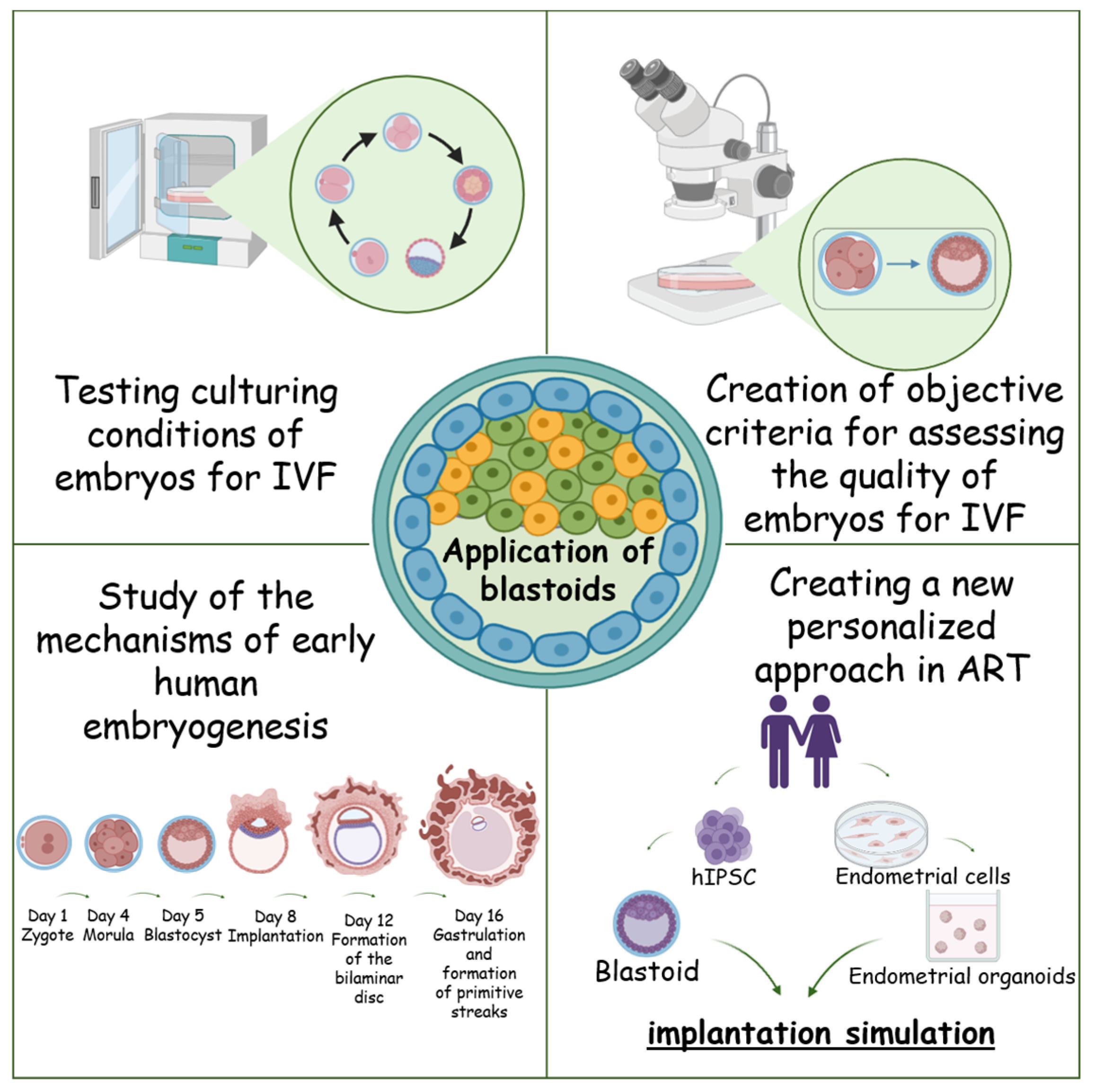

6. Application of Blastoids

7. The Problem of Identification of the Hypoblast-Like Compartment of the Blastoid

8. Naïve Pluripotency Conditions for Blastoid Formation

9. Limitations of Blastoid Application

10. Future Perspectives and Research Potential

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ART | Assisted Reproductive Technologies |

| PSC | Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| SES | Synthetic Embryo Systems |

| ICM | Inner Cell Mass |

| TSC | Trophoblast Stem Cells |

| IVF | In Vitro Fertilization |

| ISSCR | International Society for Stem Cell Research |

| LIF | Leukemia Inhibitory Factor |

| IGF | Insulin-like Growth Factors |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| CSF | Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| HB-EGF | Heparin-Binding Epidermal Growth Factor |

| PIF | Preimplantation Factor |

| MEA | Mouse Embryo Assay |

| ZGA | Zygotic Genome Activation |

| TLI | Time-Lapse Imaging |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| PGT | Preimplantation genetic testing |

| PGT-A | Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidy |

| PGT-M | Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Monogenic Disorders |

| mESC | Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells |

| iPSC | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| OKSM | OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, cMYC |

| hPSC | Human Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| EGF | Epidermal Growth Factor |

| VGLL1 | Vestigial-like family member 1 |

| TE | Trophectoderm |

| HYP | Hypoblast |

| PrE | Primitive Endoderm |

| EPSC | Extended Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor β |

| LPA | Lysophosphatidic acid |

| EPI | Epiblast |

| 5iLAF | 5 inhibitors + LIF + Activin A + FGF2 |

| 4CL | 4-component culture with LIF |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

References

- Biggers, J.D.; Moore, B.D.; Whittingham, D.G. Development of Mouse Embryos in Vivo after Cultivation from Two-Cell Ova to Blastocysts In Vitro. Nature 1965, 206, 734–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, A.; Biggers, J.D. Successful Development and Birth of Mice Cultivated In Vitro as Early Embryos. Nature 1958, 182, 877–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condic, M.L. Totipotency: What It Is and What It Is Not. Stem Cells Dev. 2014, 23, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoda, K.; Kime, C. Synthetic Embryology: Early Mammalian Embryo Modeling Systems from Cell Cultures. Dev. Growth Differ. 2021, 63, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagimachi, R. Mechanisms of Fertilization in Mammals. In Fertilization and Embryonic Development In Vitro; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.G.; Bavister, B.D.; Steptoe, P.C. Early Stages of Fertilization In Vitro of Human Oocytes Matured In Vitro. Nature 1969, 221, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.G.; Steptoe, P.C.; Purdy, J.M. Fertilization and Cleavage In Vitro of Preovulator Human Oocytes. Nature 1970, 227, 1307–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, M.F. Human Embryo Research and the 14-Day Rule. Development 2017, 144, 1923–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.J.; Kaufman, M.H. Establishment in Culture of Pluripotential Cells from Mouse Embryos. Nature 1981, 292, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, J.A. Embryonic Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Blastocysts. Science 1998, 282, 1145–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deglincerti, A.; Croft, G.F.; Pietila, L.N.; Zernicka-Goetz, M.; Siggia, E.D.; Brivanlou, A.H. Self-Organization of the In Vitro Attached Human Embryo. Nature 2016, 533, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbazi, M.N.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Deconstructing and Reconstructing the Mouse and Human Early Embryo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, B.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Shi, C.; Xu, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, C.; Lai, W.; et al. Derivation of Pluripotent Stem Cells with In Vivo Embryonic and Extraembryonic Potency. Cell 2017, 169, 243–257.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivron, N.C.; Frias-Aldeguer, J.; Vrij, E.J.; Boisset, J.C.; Korving, J.; Vivié, J.; Truckenmüller, R.K.; Van Oudenaarden, A.; Van Blitterswijk, C.A.; Geijsen, N. Blastocyst-like Structures Generated Solely from Stem Cells. Nature 2018, 557, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Min, Z.; Alsolami, S.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, E.; Chen, W.; Zhong, K.; Pei, W.; Kang, X.; Zhang, P.; et al. Generation of Human Blastocyst-like Structures from Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tan, J.P.; Schröder, J.; Aberkane, A.; Ouyang, J.F.; Mohenska, M.; Lim, S.M.; Sun, Y.B.Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, G.; et al. Modelling Human Blastocysts by Reprogramming Fibroblasts into IBlastoids. Nature 2021, 591, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wei, Y.; Duan, J.; Schmitz, D.A.; Sakurai, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, K.; Zhao, S.; Hon, G.C.; Wu, J. Blastocyst-like Structures Generated from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Nature 2021, 591, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, H.; Javali, A.; Khoei, H.H.; Sommer, T.M.; Sestini, G.; Novatchkova, M.; Scholte op Reimer, Y.; Castel, G.; Bruneau, A.; Maenhoudt, N.; et al. Human Blastoids Model Blastocyst Development and Implantation. Nature 2022, 601, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Wu, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Gong, A.; Guan, W.; Karvas, R.M.; Wang, K.; Min, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Self-Renewing Human Naïve Pluripotent Stem Cells Dedifferentiate in 3D Culture and Form Blastoids Spontaneously. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari Khoei, H.; Javali, A.; Kagawa, H.; Sommer, T.M.; Sestini, G.; David, L.; Slovakova, J.; Novatchkova, M.; Scholte op Reimer, Y.; Rivron, N. Generating Human Blastoids Modeling Blastocyst-Stage Embryos and Implantation. Nat. Protoc. 2023, 18, 1584–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Logsdon, D.; Pinzon-Arteaga, C.A.; Duan, J.; Ezashi, T.; Wei, Y.; Ribeiro Orsi, A.E.; Oura, S.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; et al. Large-Scale Production of Human Blastoids Amenable to Modeling Blastocyst Development and Maternal-Fetal Cross Talk. Cell Stem Cell 2023, 30, 1246–1261.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; An, C.; Bai, B.; Luo, J.; Sun, N.; Ci, B.; Jin, L.; Mo, P.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, K.; et al. Modeling Early Gastrulation in Human Blastoids with DNA Methylation Patterns of Natural Blastocysts. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 409–425.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.; Silva, J.; Roode, M.; Smith, A. Suppression of Erk Signalling Promotes Ground State Pluripotency in the Mouse Embryo. Development 2009, 136, 3215–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuka, S.; Nakai-Futatsugi, Y.; Niwa, H. LIF Signal in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells. Jak-Stat 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Barrandon, O.; Nichols, J.; Kawaguchi, J.; Theunissen, T.W.; Smith, A. Promotion of Reprogramming to Ground State Pluripotency by Signal Inhibition. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashima, Y.; Guo, G.; Loos, R.; Nichols, J.; Ficz, G.; Krueger, F.; Oxley, D.; Santos, F.; Clarke, J.; Mansfield, W.; et al. Resetting Transcription Factor Control Circuitry toward Ground-State Pluripotency in Human. Cell 2014, 158, 1254–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, C.B.; Nelson, A.M.; Mecham, B.; Hesson, J.; Zhou, W.; Jonlin, E.C.; Jimenez-Caliani, A.J.; Deng, X.; Cavanaugh, C.; Cook, S.; et al. Derivation of Naïve Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4484–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadei, G.; Handford, C.E.; Qiu, C.; De Jonghe, J.; Greenfeld, H.; Tran, M.; Martin, B.K.; Chen, D.Y.; Aguilera-Castrejon, A.; Hanna, J.H.; et al. Embryo Model Completes Gastrulation to Neurulation and Organogenesis. Nature 2022, 610, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Brink, S.C.; van Oudenaarden, A. 3D Gastruloids: A Novel Frontier in Stem Cell-Based In Vitro Modeling of Mammalian Gastrulation. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31, 747–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haremaki, T.; Metzger, J.J.; Rito, T.; Ozair, M.Z.; Etoc, F.; Brivanlou, A.H. Self-Organizing Neuruloids Model Developmental Aspects of Huntington’s Disease in the Ectodermal Compartment. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, J.; Song, Q.; Keshavarz, F.K.; Alavi, A.; Schoenberger, R.; LeGraw, R.; Velazquez, J.J.; Mokhtari, T.; Taheri, M.N.; Rytel, M.; et al. Modelling Post-Implantation Human Development to Yolk Sac Blood Emergence. Nature 2024, 626, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Lv, J.; Xiao, Z.; Ding, L.; Zhou, Q. A Framework for the Responsible Reform of the 14-Day Rule in Human Embryo Research. Protein Cell 2022, 13, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, J.B.; Bredenoord, A.L. Should the 14-day Rule for Embryo Research Become the 28-day Rule? EMBO Mol. Med. 2018, 10, e9437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foreman, A.L.; Liddell, K.; Franklin, S.; Jackson, E.; Rozeik, C.; Niakan, K.K. Human Embryo Models: The Importance of National Policy and Governance Review. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2023, 82, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, S.; Mantziou, V.; Moris, N.; Martinez Arias, A. Human Gastrulation: The Embryo and Its Models. Dev. Biol. 2021, 474, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, I.; Wilkerson, A.; Johnston, J. Embryology Policy: Revisit the 14-Day Rule. Nature 2016, 533, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, F.J.; Mendz, G.L. Twinning and Individuation: An Appraisal of the Current Model and Ethical Implications. Biology 2025, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, J.; Martin, K.; Spyropoulou, I.; Barlow, D.; Sargent, I.; Mardon, H. An In-Vitro Model for Stromal Invasion during Implantation of the Human Blastocyst. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 18, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurlbut, J.B.; Hyun, I.; Levine, A.D.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Lunshof, J.E.; Matthews, K.R.W.; Mills, P.; Murdoch, A.; Pera, M.F.; Scott, C.T.; et al. Revisiting the Warnock Rule. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell-Badge, R.; Anthony, E.; Barker, R.A.; Bubela, T.; Brivanlou, A.H.; Carpenter, M.; Charo, R.A.; Clark, A.; Clayton, E.; Cong, Y.; et al. ISSCR Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Clinical Translation: The 2021 Update. Stem Cell Rep. 2021, 16, 1398–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzati, M.; Djahanbakhch, O.; Arian, S.; Carr, B.R. Tubal Transport of Gametes and Embryos: A Review of Physiology and Pathophysiology. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2014, 31, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, G.E. Estimating Limits for Natural Human Embryo Mortality. F1000Research 2016, 5, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croxatto, H.B. Physiology of Gamete and Embryo Transport through the Fallopian Tube. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2002, 4, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coy, P.; García-Vázquez, F.A.; Visconti, P.E.; Avilés, M. Roles of the Oviduct in Mammalian Fertilization. Reproduction 2012, 144, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualtieri, R.; De Gregorio, V.; Candela, A.; Travaglione, A.; Genovese, V.; Barbato, V.; Talevi, R. In Vitro Culture of Mammalian Embryos: Is There Room for Improvement? Cells 2024, 13, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wydooghe, E.; Vandaele, L.; Heras, S.; De Sutter, P.; Deforce, D.; Peelman, L.; De Schauwer, C.; Van Soom, A. Autocrine Embryotropins Revisited: How Do Embryos Communicate with Each Other In Vitro When Cultured in Groups? Biol. Rev. 2017, 92, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, E.A.; Stephens, K.K.; Winuthayanon, W. Extracellular Vesicles and the Oviduct Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Winuthayanon, W. Oviduct: Roles in Fertilization and Early Embryo Development. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 232, R1–R26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinan, E.B.; Abbondanzo, S.J.; Anderson, P.S.; Pollard, J.W.; Lessey, B.A.; Stewart, C.L. Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) and LIF Receptor Expression in Human Endometrium Suggests a Potential Autocrine/Paracrine Function in Regulating Embryo Implantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 3115–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzeloglu-Kayisli, O.; Kayisli, U.A.; Taylor, H.S. The Role of Growth Factors and Cytokines during Implantation:Endocrine and Paracrine Interactions. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2009, 27, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, K.; Westwood, M.; Baker, P.N.; Aplin, J.D. Insulin-like Growth Factor I and II Regulate the Life Cycle of Trophoblast in the Developing Human Placenta. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008, 294, C1313–C1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramer, I.; Kanninen, T.T.; Sisti, G.; Witkin, S.S.; Spandorfer, S.D. Association of In Vitro Fertilization Outcome with Circulating Insulin-like Growth Factor Components Prior to Cycle Initiation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 356.e1–356.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yi, H.; Li, T.C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, X. Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (Vegf) in Human Embryo Implantation: Clinical Implications. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardo, L.G. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression in the Endometrium during the Menstrual Cycle, Implantation Window and Early Pregnancy. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 17, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhard, A.; Bentin-Ley, U.; Ravn, V.; Islin, H.; Hviid, T.; Rex, S.; Bangsboll, S.; Sorensen, S. Biochemical Evaluation of Endometrial Function at the Time of Implantation. Fertil. Steril. 2002, 78, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.J.; Dey, S.K. HB-EGF: A Unique Mediator of Embryo-Uterine Interactions during Implantation. Exp. Cell Res. 2009, 315, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Hu, R.; Zhao, J.; Ha, L.; Ma, X.; Ma, L.; Chen, Y. Expression of Heparin-Binding Epidermal Growth Factor in the Endometrium Is Positively Correlated with IVF-ET Pregnancy Outcome. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2016, 9, 8280–8285. [Google Scholar]

- Duzyj, C.M.; Barnea, E.R.; Li, M.; Huang, S.J.; Krikun, G.; Paidas, M.J. Preimplantation Factor Promotes First Trimester Trophoblast Invasion. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 203, 402.e1–402.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consensus Group, C. ‘There Is Only One Thing That Is Truly Important in an IVF Laboratory: Everything’ Cairo Consensus Guidelines on IVF Culture Conditions. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2020, 40, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigger, M.; Schneider, M.; Feldmann, A.; Assenmacher, S.; Zevnik, B.; Tröder, S.E. Successful Use of HTF as a Basal Fertilization Medium during SEcuRe Mouse In Vitro Fertilization. BMC Res. Notes 2023, 16, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ménézo, Y.J.R.; Hérubel, F. Mouse and Bovine Models for Human IVF. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2002, 4, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Fu, J. Synthetic Human Embryology: Towards a Quantitative Future. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2020, 63, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulou, M.; Sfakianoudis, K.; Rapani, A.; Giannelou, P.; Anifandis, G.; Bolaris, S.; Pantou, A.; Lambropoulou, M.; Pappas, A.; Deligeoroglou, E.; et al. Considerations Regarding Embryo Culture Conditions: From Media to Epigenetics. Vivo 2018, 32, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagers, M.; Laverde, M.; Schrauwen, F.; De Groot, J.; Vaz, F.; Mastenbroek, S. O-008 The Composition of Commercially Available Human Preimplantation Embryo Culture Media. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 38 (Suppl. 1), dead093.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunde, A.; Brison, D.; Dumoulin, J.; Harper, J.; Lundin, K.; Magli, M.C.; Van Den Abbeel, E.; Veiga, A. Time to Take Human Embryo Culture Seriously. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 2174–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coy, P.; Romar, R.; Romero-Aguirregomezcorta, J. The Embryo Culture Media in the Era of Epigenetics: Is It Time to Go Back to Nature? Anim. Reprod. 2022, 19, e20210132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, N.; Haaf, T. Epigenetic Disturbances in In Vitro Cultured Gametes and Embryos: Implications for Human Assisted Reproduction. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducreux, B.; Barberet, J.; Guilleman, M.; Pérez-Palacios, R.; Teissandier, A.; Bourc’his, D.; Fauque, P. Assessing the Influence of Distinct Culture Media on Human Pre-Implantation Development Using Single-Embryo Transcriptomics. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1155634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, C.; Xu, J.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; Du, Y.; Xie, L.; Zhao, J.; et al. Rapid Generation of Gene-Targeted EPS-Derived Mouse Models through Tetraploid Complementation. Protein Cell 2019, 10, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitschak, M.; Langhammer, M.; Schneider, F.; Renne, U.; Vanselow, J. Two High-Fertility Mouse Lines Show Differences in Component Fertility Traits after Long-Term Selection. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2007, 19, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, F. Zygotic Gene Activation in Mice: Profile and Regulation. J. Reprod. Dev. 2022, 68, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; DeMayo, F.J. Animal Models of Implantation. Reproduction 2004, 128, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Yu, H.; An, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Li, Z. Profiling the Transcriptomic Signatures and Identifying the Patterns of Zygotic Genome Activation—A Comparative Analysis between Early Porcine Embryos and Their Counterparts in Other Three Mammalian Species. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazer, F.W.; Johnson, G.A. Early Embryonic Development in Agriculturally Important Species. Animals 2024, 14, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.A.; Minela, T.; Seo, H.; Bazer, F.W.; Burghardt, R.C.; Wu, G.; Pohler, K.G.; Stenhouse, C.; Cain, J.W.; Seekford, Z.K.; et al. Conceptus Elongation, Implantation, and Early Placental Development in Species with Central Implantation: Pigs, Sheep, and Cows. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, A.; Krebs, S.; Heininen-Brown, M.; Zakhartchenko, V.; Blum, H.; Wolf, E. Genome Activation in Bovine Embryos: Review of the Literature and New Insights from RNA Sequencing Experiments. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 149, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, K.M.; Ortega, M.S.; Johnson, G.A.; Seo, H.; Spencer, T.E. Review: Implantation and Placentation in Ruminants. Animal 2023, 17, 100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Huang, K.; Zeng, Q.; Feng, Y.; Ke, Q.; An, Q.; Qin, L.J.; Cui, Y.G.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, D.; et al. Single-Cell Analysis of Nonhuman Primate Preimplantation Development in Comparison to Humans and Mice. Dev. Dyn. 2021, 250, 974–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckett, W.P. Origin and Differentiation of the Yolk Sac and Extraembryonic Mesoderm in Presomite Human and Rhesus Monkey Ehbryos. Am. J. Anat. 1978, 152, 59–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitanio, J.P.; Kyes, R.C.; Fairbanks, L.A. Considerations in the Selection and Conditioning of Old World Monkeys for Laboratory Research: Animals from Domestic Sources. ILAR J. 2006, 47, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, M.J. Ethical and Welfare Implications of Genetically Altered Non-Human Primates for Biomedical Research. J. Appl. Anim. Ethics Res. 2020, 2, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancsovits, P.; Pribenszky, C.; Lehner, A.; Murber, A.; Kaszas, Z.; Nemes, A.; Urbancsek, J. Prospective-Randomized Study Comparing Clinical Outcomes of IVF Treatments Where Embryos Were Cultured Individually or in a Microwell Group Culture Dish. Biol. Futur. 2022, 73, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruíz, M.; Santamaría-López, E.; Blasco, V.; Hernáez, M.J.; Caligara, C.; Pellicer, A.; Fernández-Sánchez, M.; Prados, N. Effect of Group Embryo Culture under Low-Oxygen Tension in Benchtop Incubators on Human Embryo Culture: Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 27, 1522–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ver Milyea, M.; Hall, J.M.M.; Diakiw, S.M.; Johnston, A.; Nguyen, T.; Perugini, D.; Miller, A.; Picou, A.; Murphy, A.P.; Perugini, M. Development of an Artificial Intelligence-Based Assessment Model for Prediction of Embryo Viability Using Static Images Captured by Optical Light Microscopy during IVF. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 35, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racowsky, C.; Vernon, M.; Mayer, J.; Ball, G.D.; Behr, B.; Pomeroy, K.O.; Wininger, D.; Gibbons, W.; Conaghan, J.; Stern, J.E. Standardization of Grading Embryo Morphology. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2010, 27, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Sato, T.; Nagaya, M.; Saito, C.; Yoshihara, H.; Banno, C.; Matsumoto, Y.; Matsuda, Y.; Yoshikai, K.; Sawada, T.; et al. Evaluation of Artificial Intelligence Using Time-Lapse Images of IVF Embryos to Predict Live Birth. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2021, 43, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hew, Y.; Kutuk, D.; Duzcu, T.; Ergun, Y.; Basar, M. Artificial Intelligence in IVF Laboratories: Elevating Outcomes Through Precision and Efficiency. Biology 2024, 13, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, R.; Maione, A.; Vallefuoco, A.; Sorrentino, U.; Zuccarello, D. Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Genetic Diseases: Limits and Review of Current Literature. Genes 2023, 14, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capalbo, A.; Ubaldi, F.M.; Rienzi, L.; Scott, R.; Treff, N. Detecting Mosaicism in Trophectodermbiopsies: Current Challenges and Future Possibilities. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 492–498. [Google Scholar]

- Rubino, P.; Tapia, L.; Ruiz de Assin Alonso, R.; Mazmanian, K.; Guan, L.; Dearden, L.; Thiel, A.; Moon, C.; Kolb, B.; Norian, J.M.; et al. Trophectoderm Biopsy Protocols Can Affect Clinical Outcomes: Time to Focus on the Blastocyst Biopsy Technique. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Sugiura-Ogasawara, M.; Ozawa, F.; Yamamoto, T.; Kato, T.; Kurahashi, H.; Kuroda, T.; Aoyama, N.; Kato, K.; Kobayashi, R.; et al. Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidy: A Comparison of Live Birth Rates in Patients with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Due to Embryonic Aneuploidy or Recurrent Implantation Failure. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 2340–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Rito, T.; Metzger, J.; Naftaly, J.; Soman, R.; Hu, J.; Albertini, D.F.; Barad, D.H.; Brivanlou, A.H.; Gleicher, N. Depletion of Aneuploid Cells in Human Embryos and Gastruloids. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, T.; Davis, C.; Xanthopoulou, L.; Bakosi, E.; He, C.; O’Neill, H.; Ottolini, C.S. Current Quantitative Methodologies for Preimplantation Genetic Testing Frequently Misclassify Meiotic Aneuploidies as Mosaic. Fertil. Steril. 2025, 124, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, A.V.; Krapivin, M.I.; Malysheva, O.V.; Komarova, E.M.; Golubeva, A.V.; Efimova, O.A.; Pendina, A.A. Re-Examination of PGT-A Detected Genetic Pathology in Compartments of Human Blastocysts: A Series of 23 Cases. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; DeWan, A.T.; Desai, M.M.; Vermund, S.H. Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidy: Challenges in Clinical Practice. Hum. Genom. 2022, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, H.W.; Oehninger, S.; Bocca, S.; Stadtmauer, L.; Mayer, J. Reproductive Efficiency of Human Oocytes Fertilized In Vitro. Facts Views Vis. Obgyn. 2010, 2, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ojosnegros, S.; Seriola, A.; Godeau, A.L.; Veiga, A. Embryo Implantation in the Laboratory: An Update on Current Techniques. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2021, 27, 501–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paepe, C.; Krivega, M.; Cauffman, G.; Geens, M.; van de Velde, H. Totipotency and Lineage Segregation in the Human Embryo. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 20, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossant, J. Human Embryology: Implantation Barrier Overcome. Nature 2016, 533, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Laronde, S.; Collins, T.J.; Shapovalova, Z.; Tanasijevic, B.; McNicol, J.D.; Fiebig-Comyn, A.; Benoit, Y.D.; Lee, J.B.; Mitchell, R.R.; et al. Lineage-Specific Differentiation Is Influenced by State of Human Pluripotency. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdyev, V.K.; Alpeeva, E.V.; Kalistratova, E.N.; Vorotelyak, E.A.; Vasiliev, A.V. Transformation of Pluripotency States during Morphogenesis of Mouse and Human Epiblast. Russ. J. Dev. Biol. 2024, 54, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, M.N.; Bakhmet, E.I.; Tomilin, A.N. Pluripotency Dynamics during Embryogenesis and in Cell Culture. Russ. J. Dev. Biol. 2021, 52, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Q.L.; Wray, J.; Nichols, J.; Batlle-Morera, L.; Doble, B.; Woodgett, J.; Cohen, P.; Smith, A. The Ground State of Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal. Nature 2008, 453, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloussov, L.V.; Yermakov, A.S.; Louchinskaya, N.N. Cytomechanical Control of Morphogenesis. Tsitologiya 2000, 42, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, M.; Smith, A. Pluripotency Deconstructed. Dev. Growth Differ. 2018, 60, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgani, S.; Nichols, J.; Hadjantonakis, A.K. The Many Faces of Pluripotency: In Vitro Adaptations of a Continuum of in Vivo States. BMC Dev. Biol. 2017, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, A.; van Genderen, E.; Escudero, I.; Verwegen, L.; Kurek, D.; Lehmann, J.; Stel, J.; Dirks, R.A.M.; van Mierlo, G.; Maas, A.; et al. In Vitro Capture and Characterization of Embryonic Rosette-Stage Pluripotency between Naive and Primed States. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Kaufman-Francis, K.; Studdert, J.B.; Steiner, K.A.; Power, M.D.; Loebel, D.A.F.; Jones, V.; Hor, A.; De Alencastro, G.; Logan, G.J.; et al. The Transcriptional and Functional Properties of Mouse Epiblast Stem Cells Resemble the Anterior Primitive Streak. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Okamoto, I.; Sasaki, K.; Yabuta, Y.; Iwatani, C.; Tsuchiya, H.; Seita, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Saitou, M. A Developmental Coordinate of Pluripotency among Mice, Monkeys and Humans. Nature 2016, 537, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niwa, H.; Ogawa, K.; Shimosato, D.; Adachi, K. A Parallel Circuit of LIF Signalling Pathways Maintains Pluripotency of Mouse ES Cells. Nature 2009, 460, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernemann, C.; Greber, B.; Ko, K.; Sterneckert, J.; Han, D.W.; Araúzo-Bravo, M.J.; Schöler, H.R. Distinct Developmental Ground States of Epiblast Stem Cell Lines Determine Different Pluripotency Features. Stem. Cells 2011, 29, 1496–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, N.Y.; Chan, Y.S.; Feng, B.; Lu, X.; Orlov, Y.L.; Moreau, D.; Kumar, P.; Yang, L.; Jiang, J.; Lau, M.S.; et al. A Genome-Wide RNAi Screen Reveals Determinants of Human Embryonic Stem Cell Identity. Nature 2010, 468, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Choi, M.; Margineantu, D.; Margaretha, L.; Hesson, J.; Cavanaugh, C.; Blau, C.A.; Horwitz, M.S.; Hockenbery, D.; Ware, C.; et al. HIF1α Induced Switch from Bivalent to Exclusively Glycolytic Metabolism during ESC-to-EpiSC/HESC Transition. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 2103–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brons, I.G.M.; Smithers, L.E.; Trotter, M.W.B.; Rugg-Gunn, P.; Sun, B.; Chuva De Sousa Lopes, S.M.; Howlett, S.K.; Clarkson, A.; Ahrlund-Richter, L.; Pedersen, R.A.; et al. Derivation of Pluripotent Epiblast Stem Cells from Mammalian Embryos. Nature 2007, 448, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, J.; Cheng, A.W.; Saha, K.; Kim, J.; Lengner, C.J.; Soldner, F.; Cassady, J.P.; Muffat, J.; Carey, B.W.; Jaenisch, R. Human Embryonic Stem Cells with Biological and Epigenetic Characteristics Similar to Those of Mouse ESCs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9222–9227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesar, P.J.; Chenoweth, J.G.; Brook, F.A.; Davies, T.J.; Evans, E.P.; Mack, D.L.; Gardner, R.L.; McKay, R.D.G. New Cell Lines from Mouse Epiblast Share Defining Features with Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Nature 2007, 448, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durruthy, J.D.; Ramathal, C.; Sukhwani, M.; Fang, F.; Cui, J.; Orwig, K.E.; Reijo Pera, R.A. Fate of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Following Transplantation to Murine Seminiferous Tubules. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 3071–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theunissen, T.W.; Friedli, M.; He, Y.; Planet, E.; O’Neil, R.C.; Markoulaki, S.; Pontis, J.; Wang, H.; Iouranova, A.; Imbeault, M.; et al. Molecular Criteria for Defining the Naive Human Pluripotent State. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 19, 502–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tietze, E.; Barbosa, A.R.; Araujo, B.; Euclydes, V.; Spiegelberg, B.; Cho, H.J.; Lee, Y.K.; Wang, Y.; McCord, A.; Lorenzetti, A.; et al. Human Archetypal Pluripotent Stem Cells Differentiate into Trophoblast Stem Cells via Endogenous BMP5/7 Induction without Transitioning through Naive State. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Jia, W.; Luo, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Fu, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Lai, J.; Li, H.; et al. VGLL1 Cooperates with TEAD4 to Control Human Trophectoderm Lineage Specification. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, T.; Rivron, N.; Kabata, M.; Masaki, H.; Kishimoto, K.; Semi, K.; Nakajima-Koyama, M.; Kunitomi, H.; Kaswandy, B.; Sato, H.; et al. Hypoblast from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells Regulates Epiblast Development. Nature 2024, 626, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azagury, M.; Buganim, Y. Unlocking Trophectoderm Mysteries: In Vivo and In Vitro Perspectives on Human and Mouse Trophoblast Fate Induction. Dev. Cell 2024, 59, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, S.; Hadjantonakis, A.K. Journey of the Mouse Primitive Endoderm: From Specification to Maturation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2022, 377, 20210252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohinata, Y.; Endo, T.A.; Sugishita, H.; Watanabe, T.; Iizuka, Y.; Kawamoto, Y.; Saraya, A.; Kumon, M.; Koseki, Y.; Kondo, T.; et al. Establishment of Mouse Stem Cells That Can Recapitulate the Developmental Potential of Primitive Endoderm. Science 2022, 375, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.G.V.; Hamilton, W.B.; Roske, F.V.; Azad, A.; Knudsen, T.E.; Canham, M.A.; Forrester, L.M.; Brickman, J.M. Insulin fine-tunes self-renewal pathways governing naive pluripotency and extra-embryonic endoderm. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 1164–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohinata, Y.; Tsukiyama, T. Establishment of Trophoblast Stem Cells under Defined Culture Conditions in Mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blij, S.; Parenti, A.; Tabatabai-Yazdi, N.; Ralston, A. Cdx2 Efficiently Induces Trophoblast Stem-like Cells in Naïve, but Not Primed, Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem. Cells Dev. 2015, 24, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niwa, H.; Toyooka, Y.; Shimosato, D.; Strumpf, D.; Takahashi, K.; Yagi, R.; Rossant, J. Interaction between Oct3/4 and Cdx2 Determines Trophectoderm Differentiation. Cell 2005, 123, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ralston, A.; Cox, B.J.; Nishioka, N.; Sasaki, H.; Chea, E.; Rugg-Gunn, P.; Guo, G.; Robson, P.; Draper, J.S.; Rossant, J. Gata3 Regulates Trophoblast Development Downstream of Tead4 and in Parallel to Cdx2. Development 2010, 137, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Nefzger, C.M.; Rossello, F.J.; Chen, J.; Knaupp, A.S.; Firas, J.; Ford, E.; Pflueger, J.; Paynter, J.M.; Chy, H.S.; et al. Comprehensive Characterization of Distinct States of Human Naive Pluripotency Generated by Reprogramming. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, C.B.; Wang, L.; Mecham, B.H.; Shen, L.; Nelson, A.M.; Bar, M.; Lamba, D.A.; Dauphin, D.S.; Buckingham, B.; Askari, B.; et al. Histone Deacetylase Inhibition Elicits an Evolutionarily Conserved Self-Renewal Program in Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 4, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, W.A.; Chen, D.; Liu, W.; Kim, R.; Sahakyan, A.; Lukianchikov, A.; Plath, K.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Clark, A.T. Naive Human Pluripotent Cells Feature a Methylation Landscape Devoid of Blastocyst or Germline Memory. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, B.; Ueda, M.; Sabri, S.; Brumbaugh, J.; Huebner, A.J.; Sahakyan, A.; Clement, K.; Clowers, K.J.; Erickson, A.R.; Shioda, K.; et al. Reduced MEK Inhibition Preserves Genomic Stability in Naive Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayerl, J.; Ayyash, M.; Shani, T.; Manor, Y.S.; Gafni, O.; Massarwa, R.; Kalma, Y.; Aguilera-Castrejon, A.; Zerbib, M.; Amir, H.; et al. Principles of Signaling Pathway Modulation for Enhancing Human Naive Pluripotency Induction. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 1549–1565.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafni, O.; Weinberger, L.; Mansour, A.A.; Manor, Y.S.; Chomsky, E.; Ben-Yosef, D.; Kalma, Y.; Viukov, S.; Maza, I.; Zviran, A.; et al. Derivation of Novel Human Ground State Naive Pluripotent Stem Cells. Nature 2013, 504, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theunissen, T.W.; Powell, B.E.; Wang, H.; Mitalipova, M.; Faddah, D.A.; Reddy, J.; Fan, Z.P.; Maetzel, D.; Ganz, K.; Shi, L.; et al. Systematic Identification of Culture Conditions for Induction and Maintenance of Naive Human Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrier, S.; Van Der Jeught, M.; Duggal, G.; Tilleman, L.; Sutherland, E.; Taelman, J.; Popovic, M.; Lierman, S.; Chuva De Sousa Lopes, S.; Van Soom, A.; et al. Direct Comparison of Distinct Naive Pluripotent States in Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberg, S.R.; de Barros, F.R.O.; Rossant, J.; Renfree, M.B. The Mammalian Blastocyst. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2016, 5, 210–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Zhong, C.; Yu, Y.; Liu, H.; Sakurai, M.; Yu, L.; Min, Z.; Shi, L.; Wei, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; et al. Generation of Blastocyst-like Structures from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Cell Cultures. Cell 2019, 179, 687–702.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sozen, B.; Cox, A.L.; De Jonghe, J.; Bao, M.; Hollfelder, F.; Glover, D.M.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Self-Organization of Mouse Stem Cells into an Extended Potential Blastoid. Dev. Cell 2019, 51, 698–712.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-González, D.; Gidi-Grenat, M.Á.; García-López, G.; Martínez-Juárez, A.; Molina-Hernández, A.; Portillo, W.; Díaz-Martínez, N.E.; Díaz, N.F. Pluripotent Stem Cells as a Model for Human Embryogenesis. Cells 2023, 12, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-González, D.; Portillo, W.; García-López, G.; Molina-Hernández, A.; Díaz-Martínez, N.E.; Díaz, N.F. Unraveling the Spatiotemporal Human Pluripotency in Embryonic Development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 676998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Nowak-Imialek, M.; Chen, X.; Chen, D.; Herrmann, D.; Ruan, D.; Chen, A.C.H.; Eckersley-Maslin, M.A.; Ahmad, S.; Lee, Y.L.; et al. Establishment of Porcine and Human Expanded Potential Stem Cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Wu, J.; Si, C.; Dai, S.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, N.; Zhang, E.; Shao, H.; Si, W.; Yang, P.; et al. Chimeric Contribution of Human Extended Pluripotent Stem Cells to Monkey Embryos Ex Vivo. Cell 2021, 184, 2020–2032.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ryan, D.J.; Wang, W.; Tsang, J.C.H.; Lan, G.; Masaki, H.; Gao, X.; Antunes, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Establishment of Mouse Expanded Potential Stem Cells. Nature 2017, 550, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okae, H.; Toh, H.; Sato, T.; Hiura, H.; Takahashi, S.; Shirane, K.; Kabayama, Y.; Suyama, M.; Sasaki, H.; Arima, T. Derivation of Human Trophoblast Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 50–63.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahar, A.; Ezashi, T.; Rogers, H.; Yu, L.; Wei, Y.; Schoolcraft, W.B.; Katz-Jaffe, M.; Wu, J.; Yuan, Y. Activation of akt, mapk3/1 and mtor signaling pathways is associated with the success of cavity formation during human blastoid generation. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerri, C.; McCarthy, A.; Alanis-Lobato, G.; Demtschenko, A.; Bruneau, A.; Loubersac, S.; Fogarty, N.M.E.; Hampshire, D.; Elder, K.; Snell, P.; et al. Initiation of a Conserved Trophectoderm Program in Human, Cow and Mouse Embryos. Nature 2020, 587, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Shahbazi, M.; Martin, A.; Zhang, C.; Sozen, B.; Borsos, M.; Mandelbaum, R.S.; Paulson, R.J.; Mole, M.A.; Esbert, M.; et al. Human Embryo Polarization Requires PLC Signaling to Mediate Trophectoderm Specification. eLife 2021, 10, e65068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedzhov, I.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Self-Organizing Properties of Mouse Pluripotent Cells Initiate Morphogenesis upon Implantation. Cell 2014, 156, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maître, J.L. Mechanics of Blastocyst Morphogenesis. Biol. Cell 2017, 109, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattani, A.; Corujo-Simon, E.; Radley, A.; Heydari, T.; Taheriabkenar, Y.; Carlisle, F.; Lin, S.; Liddle, C.; Mill, J.; Zandstra, P.W.; et al. Naive Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Models Capture FGF-Dependent Human Hypoblast Lineage Specification. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 1058–1071.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Warmflash, A. Self-Organized Signaling in Stem Cell Models of Embryos. Stem Cell Rep. 2021, 16, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Jódar, M.; Ullate-Agote, A.; Barlabé, P.; Rodríguez-Madoz, J.R.; Abizanda, G.; Barreda, C.; Carvajal-Vergara, X.; Vilas-Zornoza, A.; Romero, J.P.; Garate, L.; et al. Revealing Cell Populations Catching the Early Stages of Human Embryo Development in Naive Pluripotent Stem Cell Cultures. Stem Cell Rep. 2023, 18, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, J.H.; Saha, K.; Jaenisch, R. Pluripotency and Cellular Reprogramming: Facts, Hypotheses, Unresolved Issues. Cell 2010, 143, 508–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunitomi, A.; Hirohata, R.; Osawa, M.; Washizu, K.; Arreola, V.; Saiki, N.; Kato, T.M.; Nomura, M.; Kunitomi, H.; Ohkame, T.; et al. H1FOO-DD Promotes Efficiency and Uniformity in Reprogramming to Naive Pluripotency. Stem Cell Rep. 2024, 19, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ouyang, J.F.; Rossello, F.J.; Tan, J.P.; Davidson, K.C.; Valdes, D.S.; Schröder, J.; Sun, Y.B.Y.; Chen, J.; Knaupp, A.S.; et al. Reprogramming Roadmap Reveals Route to Human Induced Trophoblast Stem Cells. Nature 2020, 586, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsalobre, A.; Drouin, J. Pioneer Factors as Master Regulators of the Epigenome and Cell Fate. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaupp, A.S.; Buckberry, S.; Pflueger, J.; Lim, S.M.; Ford, E.; Larcombe, M.R.; Rossello, F.J.; de Mendoza, A.; Alaei, S.; Firas, J.; et al. Transient and Permanent Reconfiguration of Chromatin and Transcription Factor Occupancy Drive Reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 834–845.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufi, A.; Garcia, M.F.; Jaroszewicz, A.; Osman, N.; Pellegrini, M.; Zaret, K.S. Pioneer Transcription Factors Target Partial DNA Motifs on Nucleosomes to Initiate Reprogramming. Cell 2015, 161, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, K.X.; Mason, E.A.; Kie, J.; De Souza, D.P.; Kloehn, J.; Tull, D.; McConville, M.J.; Keniry, A.; Beck, T.; Blewitt, M.E.; et al. Unique Properties of a Subset of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells with High Capacity for Self-Renewal. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Meng, Y.; Kanchanawong, P. Ground-State Pluripotent Stem Cells Are Characterized by Rac1-Dependent Cadherin-Enriched F-Actin Protrusions. J. Cell Sci. 2023, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyooka, Y. Trophoblast Lineage Specification in the Mammalian Preimplantation Embryo. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2020, 19, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, M.F. Pluripotent Cell States and Unexpected Fates. Stem Cell Rep. 2022, 17, 1235–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, S. Signaling Pathways in Human Blastocyst Development: From Molecular Mechanisms to In Vitro Optimization. J. Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinard, E.; Pasque, V.; David, L. Having a Blast(Oid): Modeling Human Embryo Peri-Implantation Development with Blastoids. Cell Stem Cell 2023, 30, 1125–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascetti, V.L.; Pedersen, R.A. Contributions of Mammalian Chimeras to Pluripotent Stem Cell Research. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 19, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, S.; Endo, S.; Nagai, L.A.E.; Kobayashi, E.H.; Oike, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Kitamura, A.; Hori, T.; Nashimoto, Y.; Nakato, R.; et al. Modeling Embryo-Endometrial Interface Recapitulating Human Embryo Implantation. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadi4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinzón-Arteaga, C.A.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Ribeiro Orsi, A.E.; Li, L.; Scatolin, G.; Liu, L.; Sakurai, M.; Ye, J.; Ming, H.; et al. Bovine Blastocyst-like Structures Derived from Stem Cell Cultures. Cell Stem Cell 2023, 30, 611–616.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhu, Q.; Cao, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Huang, Y.; Shang, S.; Bian, X.; et al. Cynomolgus Monkey Embryo Model Captures Gastrulation and Early Pregnancy. Cell Stem Cell 2023, 30, 362–377.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawai, T.; Akatsuka, K.; Okui, G.; Minakawa, T. The Regulation of Human Blastoid Research: A Bioethical Discussion of the Limits of Regulation. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e56045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrode, N.; Xenopoulos, P.; Piliszek, A.; Frankenberg, S.; Plusa, B.; Hadjantonakis, A.K. Anatomy of a Blastocyst: Cell Behaviors Driving Cell Fate Choice and Morphogenesis in the Early Mouse Embryo. Genesis 2013, 51, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrode, N.; Saiz, N.; Di Talia, S.; Hadjantonakis, A.K. GATA6 Levels Modulate Primitive Endoderm Cell Fate Choice and Timing in the Mouse Blastocyst. Dev. Cell 2014, 29, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeley, P.; Fogarty, N.M.E.; Del Valle, I.; Wamaitha, S.E.; Hu, T.X.; Elder, K.; Snell, P.; Christie, L.; Robson, P.; Niakan, K.K. Defining the Three Cell Lineages of the Human Blastocyst by Single-Cell RNA-Seq. Development 2015, 142, 3151–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corujo-Simon, E.; Radley, A.H.; Nichols, J. Evidence Implicating Sequential Commitment of the Founder Lineages in the Human Blastocyst by Order of Hypoblast Gene Activation. Development 2023, 150, dev201522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Z.; Niu, B.; Yin, Y.; Xiang, L.; Shi, G.; Duan, K.; Wang, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; et al. Dissecting Peri-Implantation Development Using Cultured Human Embryos and Embryo-like Assembloids. Cell Res. 2023, 33, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinlay, K.M.L.; Weatherbee, B.A.T.; Rosa, V.S.; Handford, C.E.; Hudson, G.; Coorens, T.; Pereira, L.V.; Behjati, S.; Vallier, L.; Shahbazi, M.N.; et al. An In Vitro Stem Cell Model of Human Epiblast and Yolk Sac Interaction. eLife 2021, 10, e63930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazid, M.A.; Ward, C.; Luo, Z.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Lai, Y.; Wu, L.; Li, J.; Jia, W.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Rolling Back Human Pluripotent Stem Cells to an Eight-Cell Embryo-like Stage. Nature 2022, 605, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ouyang, M.; Zhan, J.; Tian, R. CRISPR-Based Functional Genomics Screening in Human-Pluripotent-Stem-Cell-Derived Cell Types. Cell Genom. 2023, 3, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Li, Z.; Jin, Y.; Chandrasekaran, A.P.; Shakir, I.M.; Zhang, Y.; Siddique, A.; Wang, M.; Zhou, X.; Tian, Y.; et al. DeepBlastoid: A Deep Learning Model for Automated and Efficient Evaluation of Human Blastoids. Life Med. 2025, lnaf026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ye, P.; Xiong, W.; Duan, X.; Jing, S.; He, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Wei, Y.; Ye, Q. Genome-Scale CRISPR-Cas9 Screening in Stem Cells: Theories, Applications and Challenges. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Advantages | Limitations | Relevance to Humans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse (Mus musculus) | Low in morphology, average for genetic and molecular studies | ||

| Pig (Sus scrofa) | Implantation is superficial and is accompanied by elongation of the embryo (not typical for humans) [77] | Medium, useful for testing environments and embryo metabolism | |

| Cattle (Bos taurus) | Implantation is superficial and is accompanied by elongation of the embryo (not typical for humans) [77] | High, especially for studying culture conditions and preimplantation development | |

| Old world primates (Macaca spp.) | Very high, most relevant model among animals |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ryabchenko, A.S.; Abdyev, V.K.; Vorotelyak, E.A.; Vasiliev, A.V. Human Blastoid: A Next-Generation Model for Reproductive Medicine? Biology 2025, 14, 1439. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101439

Ryabchenko AS, Abdyev VK, Vorotelyak EA, Vasiliev AV. Human Blastoid: A Next-Generation Model for Reproductive Medicine? Biology. 2025; 14(10):1439. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101439

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyabchenko, Anfisa S., Vepa K. Abdyev, Ekaterina A. Vorotelyak, and Andrey V. Vasiliev. 2025. "Human Blastoid: A Next-Generation Model for Reproductive Medicine?" Biology 14, no. 10: 1439. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101439

APA StyleRyabchenko, A. S., Abdyev, V. K., Vorotelyak, E. A., & Vasiliev, A. V. (2025). Human Blastoid: A Next-Generation Model for Reproductive Medicine? Biology, 14(10), 1439. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101439