Spatiotemporal Frameworks of Morphogenesis and Cell Lineage Specification in Pre- and Peri-Implantation Mammalian Embryogenesis: Insights and Knowledge Gaps from Mouse Embryo

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

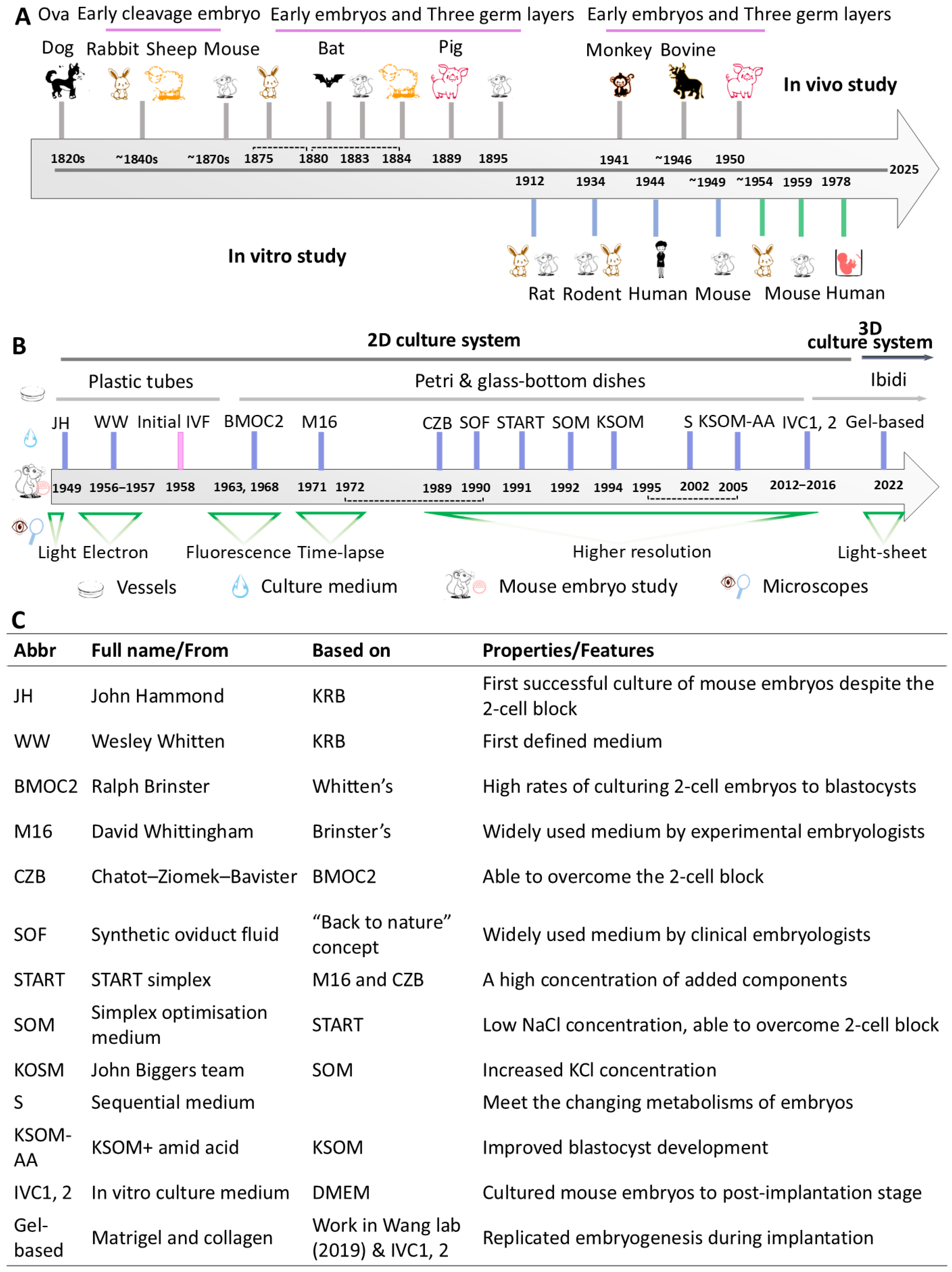

2. Mammalian Models for Studying Early Embryogenesis

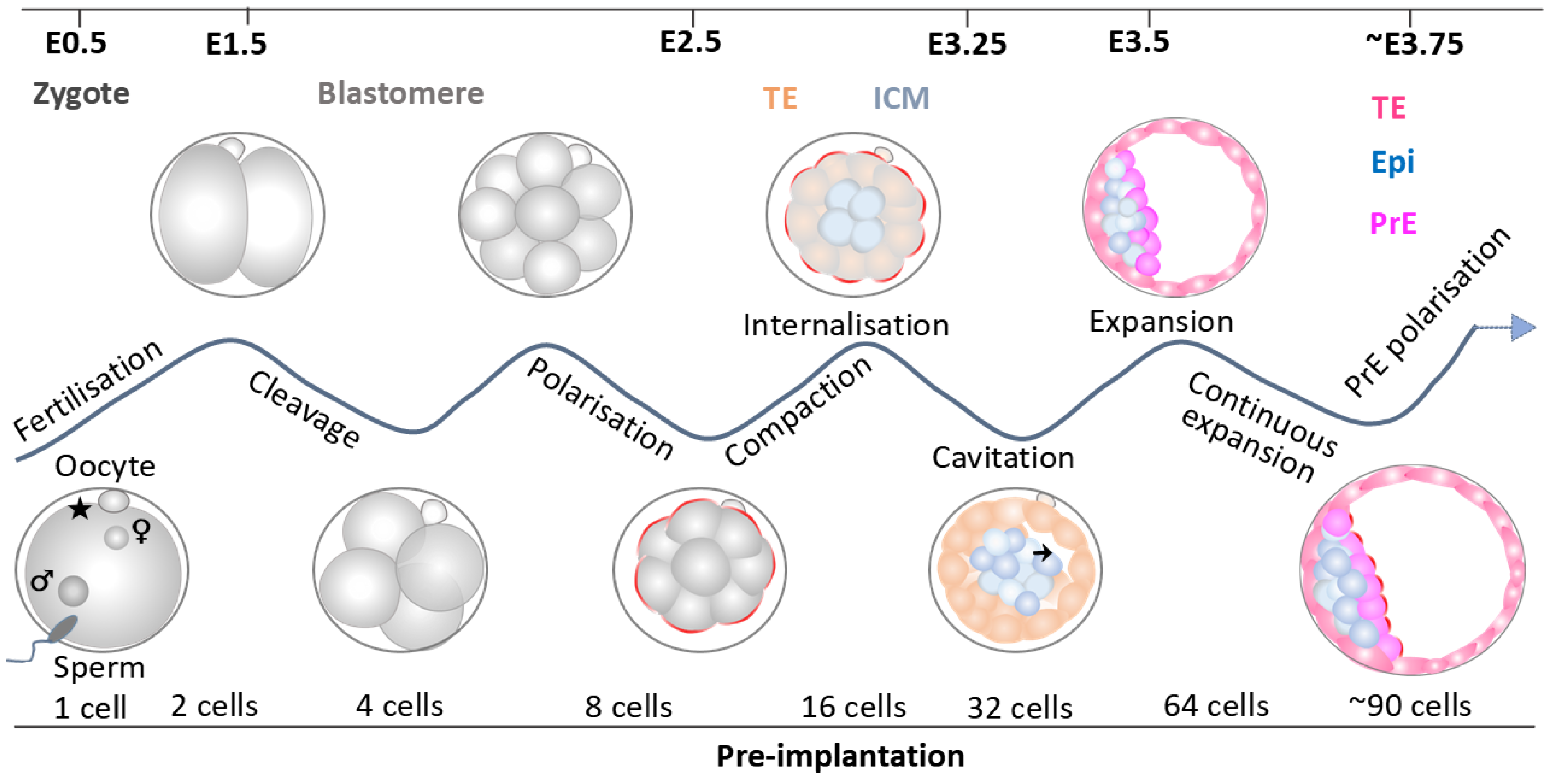

3. Landmark Morphological Events in the Pre-Implantation Embryo

3.1. Fertilisation

3.2. Compaction

3.3. Polarisation

3.4. Cell Internalisation

3.5. Cavitation

4. Key Lineage Specification in the Pre-Implantation Embryo

4.1. Prevailing Models of the First and Second Cell Lineage Specification

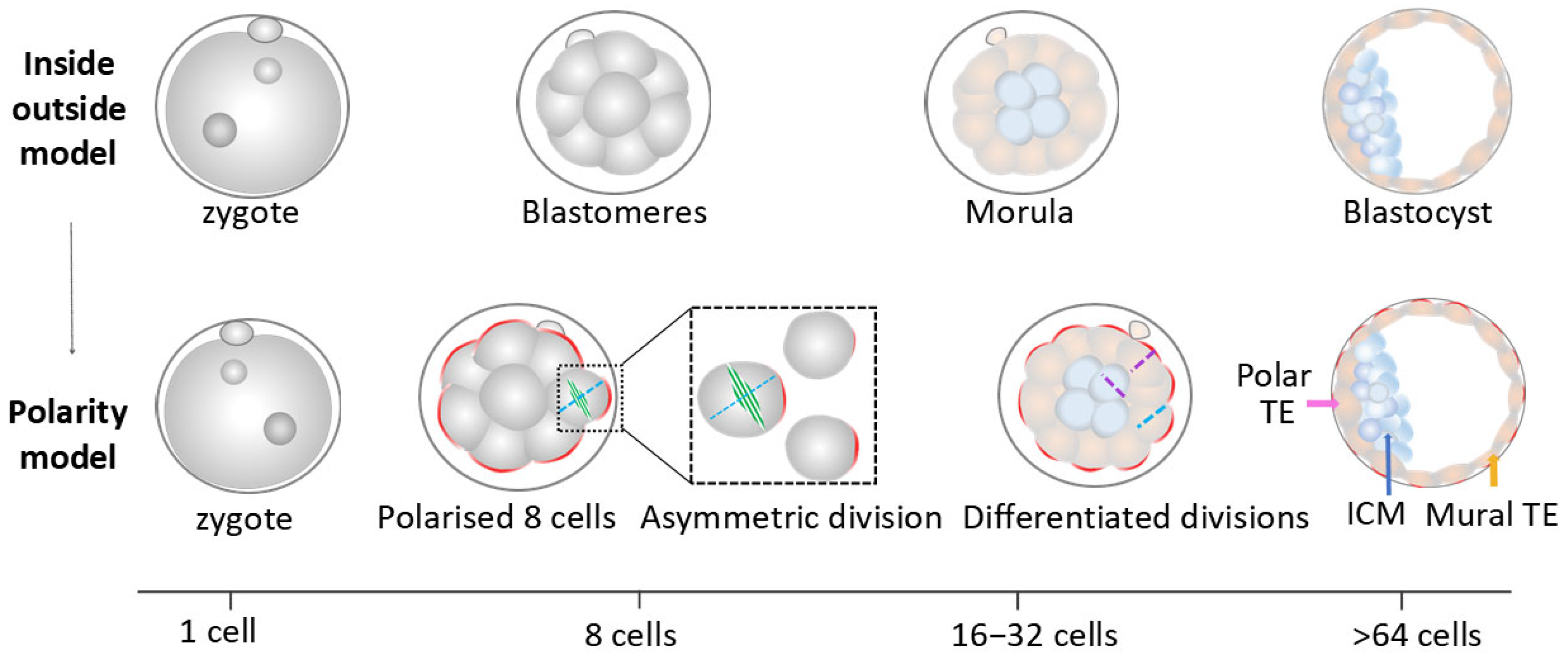

4.1.1. The First Cell Fate Decision

4.1.2. The Second Cell Lineage Specification

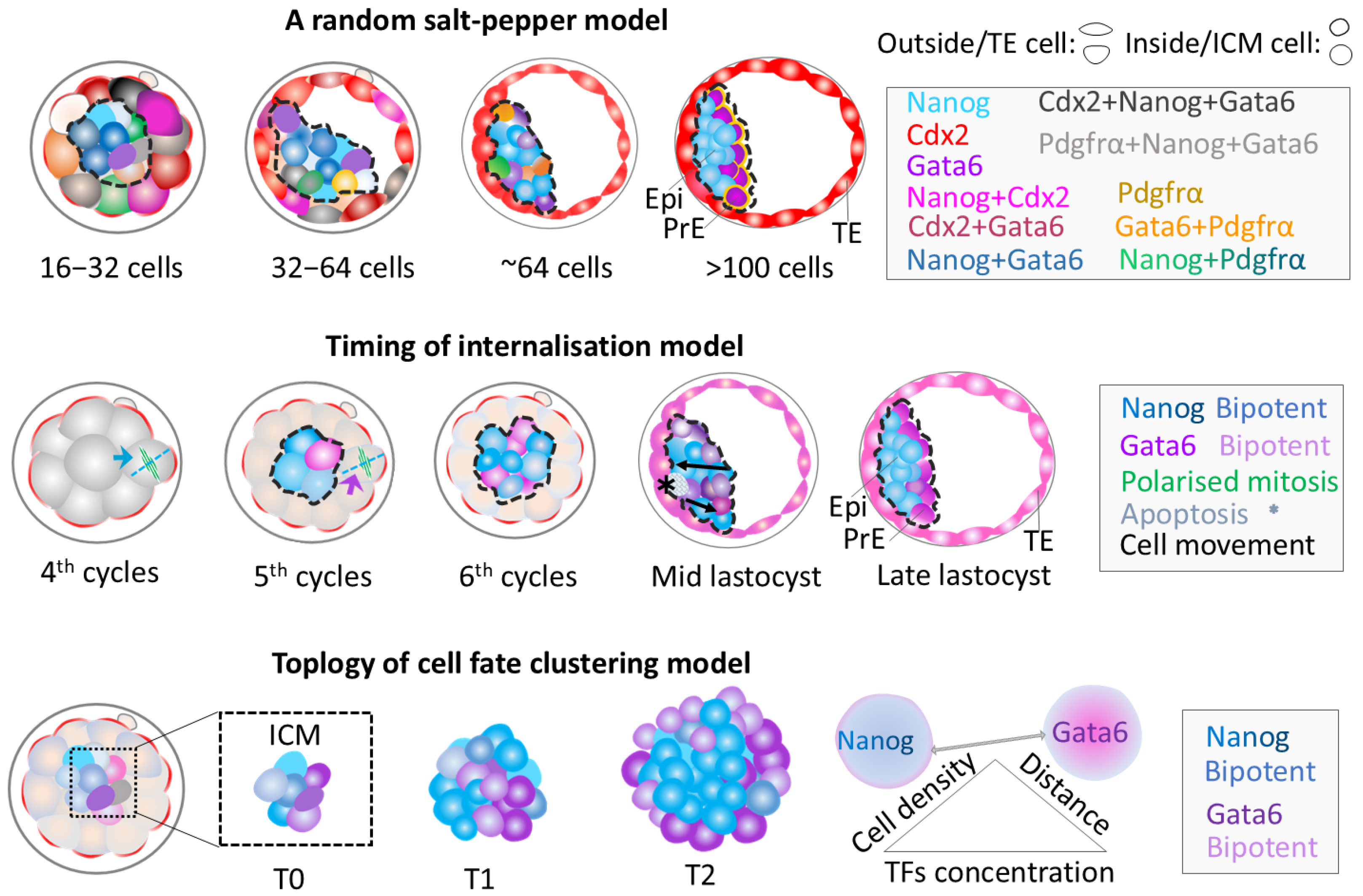

Main Models for the Second Cell Fate Decision

Synthesised Theoretical Model for the Second Cell Fate Decision

4.2. Alternative Interpretations of the First and Second Cell Lineage Specification

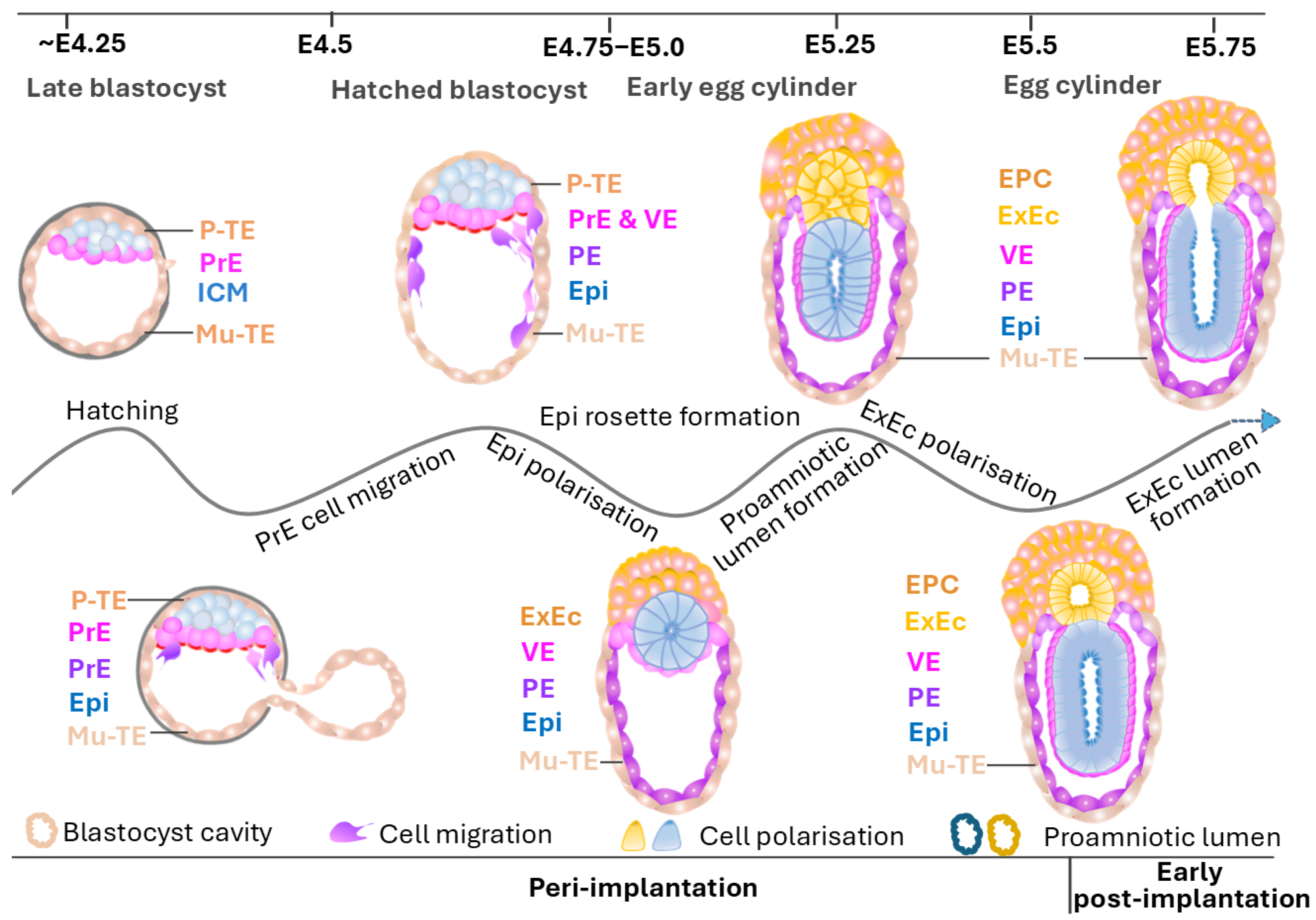

5. Key Morphological Changes in Peri-Implantation Mouse Embryo

5.1. Embryo Hatching

5.2. Cell Migration

5.3. Egg Cylinder Formation

5.4. Proamniotic Cavity Formation

6. Key Cell Lineage Establishment in Peri-Implantation Mouse Embryo

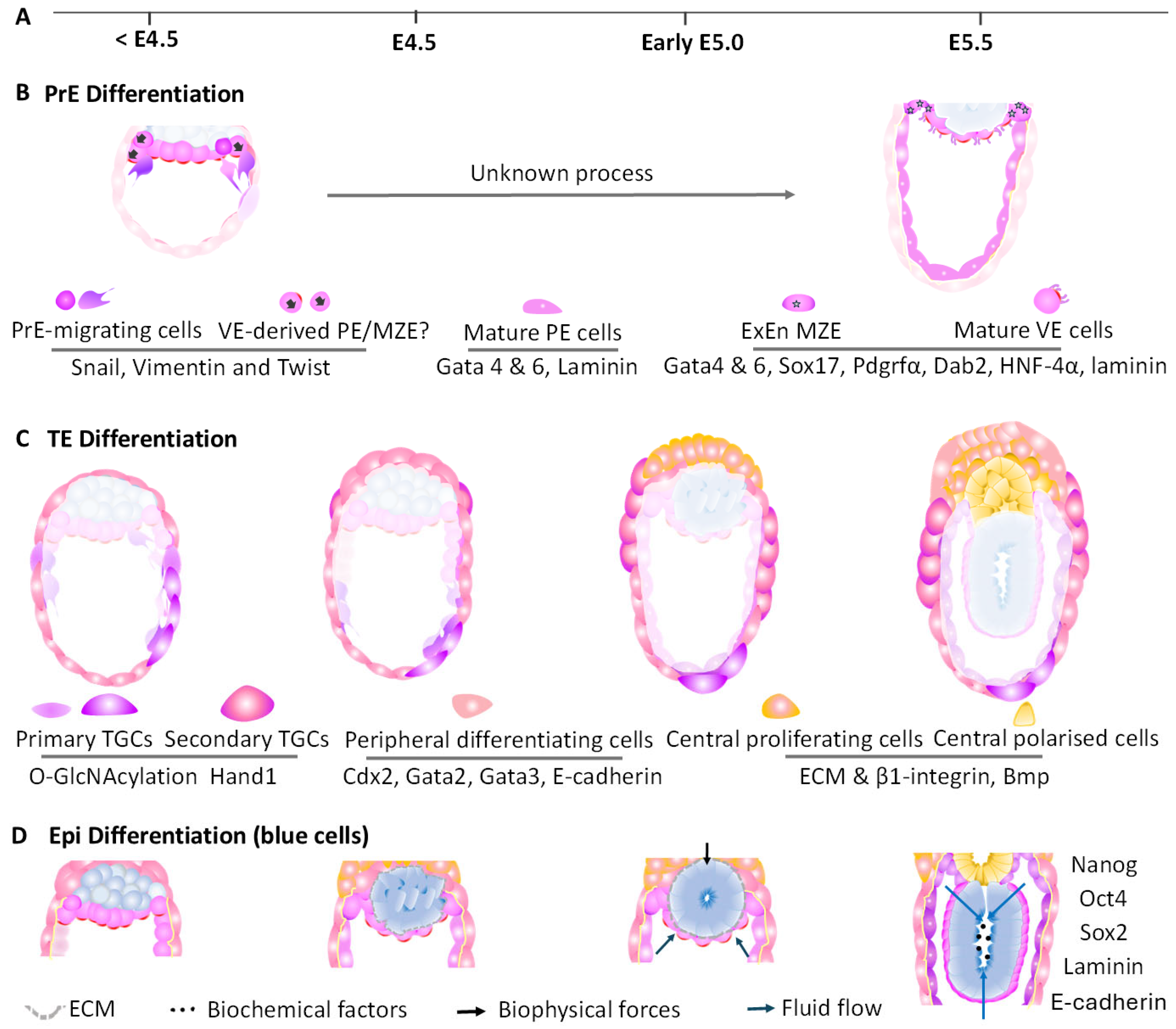

6.1. PrE Differentiation into Extraembryonic Endoderm

6.2. TE Cell Differentiation into Extraembryonic Ectoderm

6.3. Epi Development into Rosette-like Epi

7. Conclusions

8. Future Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AQP | Aquaporin |

| Bmp | Bone morphogenetic protein |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| Cdx2 | Caudal-type homeobox transcription factor 2 |

| Cd36 | CD36 molecule (Fatty acid translocase) |

| Cfb | Complement factor B |

| Dab2 | Disabled homolog 2 |

| Dlx3 | Distal-less homeobox 3 |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| Elf5 | E74-like ETS transcription factor 5 |

| EMT | Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| Eomes | Eomesodermin |

| EPC | Ectoplacental cone |

| Epi | Epiblast |

| ErK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| Ets | E26 transformation-specific family of transcription factors |

| ExEc | Extraembryonic ectoderm |

| Fgf | Fibroblast growth factor |

| Fgfr | Fibroblast growth factor receptor |

| FoxM1 | Forkhead box protein M1 |

| Gsk | Glycogen synthase kinase |

| H4K16 | Histone H4, lysine 16 |

| Hand1 | Heart and neural crest derivatives expressed 1 |

| ICM | Inner cell mass |

| Il-1α | Interleukin 1 alpha |

| Il-1β | Interleukin 1 beta |

| Il-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| Krt18 | Keratin 18 |

| Lgl | Lethal giant larvae |

| Lefty1 | Left-right determination factor 1 |

| Lyz2 | Lysozyme 2 |

| Mek/Erk | Mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| Mmp2 | Matrix metallopeptidase 2 |

| MTs | Microtubule bridges |

| MZE | Marginal zone endoderm |

| Oct4 | Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 |

| Par | Partitioning defective |

| PB2 | Second polar body |

| Pdgfrα | Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate |

| Pkl4 | Pyruvate kinase L/R |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| PLC | Phospholipase C |

| PrE | Primitive endoderm |

| Ptgs1 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 |

| PTHrP | Parathyroid hormone-related protein |

| Rb | Rho-associated protein kinase |

| Scrib | Scribble |

| Smad | Sma and Mad related protein |

| Sox2 | SRY (sex determining region Y)-box2 |

| Sox7 | SRY (sex determining region Y)-box7 |

| Sox17 | SRY (sex determining region Y)-box17 |

| Tcf24 | Transcription factor 24 |

| TE | Trophectoderm |

| TGC | Trophoblast giant cell |

| Tgf-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| Vegf | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| Wnt | Wingless-related integration site |

| ZP | Zona pellucida |

References

- Xu, R.; Li, C.; Liu, X.Y.; Gao, S.R. Insights into Epigenetic Patterns in Mammalian Early Embryos. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stower, M.J.; Srinivas, S. Advances in Live Imaging Early Mouse Development: Exploring the Researcher’s Interdisciplinary Toolkit. Development 2021, 148, dev199433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; An, J.; Peng, Y.; Kong, S.; Liu, Q.; Yang, M.; He, Q.; Song, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; et al. DevOmics: An Integrated Multi-Omics Database of Human and Mouse Early Embryo. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbab208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonica, M.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Principles of Self-Organization of the Mammalian Embryo. Cell 2020, 183, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płusa, B.; Piliszek, A. Common Principles of Early Mammalian Embryo Self-Organisation. Development 2020, 147, dev183079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zernicka-Goetz, M. Cleavage Pattern and Emerging Asymmetry of the Mouse Embryo. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motosugi, N.; Bauer, T.; Polanski, Z.; Solter, D.; Hiiragi, T. Polarity of the Mouse Embryo is Established at Blastocyst and is Not Prepatterned. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 1081–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, S.A.; Teo, R.T.Y.; Li, H.; Robson, P.; Glover, D.M.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Origin and Formation of the First Two Distinct Cell Types of the Inner Cell Mass in the Mouse Blastocyst. Nat. Commun. 2010, 8, 921. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka, Y.; Lanner, F.; Rossant, J. FGF Signal-Dependent Segregation of Primitive Endoderm and Epiblast in the Mouse Blastocyst. Development 2010, 137, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962; pp. 1–264. [Google Scholar]

- Colonna, F.T. De Ovi Mammalium et Hominis Genesi (1827), by Karl Ernst von Baer. Embryo Project Encyclopedia 2017. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10776/11405 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Van Beneden, E. Recherches sur l’embryologie des Mammifères. La formation des feuillets chez le Lapin. Arch. Biol. 1880, 1, 137–224. [Google Scholar]

- Van Beneden, E.; Julin, C. Observations sur la maturation, la fécondation et la segmentation de l’œuf chez les Chéiroptères. Arch. Biol. 1880, 1, 551–571. [Google Scholar]

- Brachet, A. Développement in vitro de blastodermes et de jeunes embryons de mammifères. Comptes Rendus Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 1912, 155, 1191–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, E.L.; Long, J.A. The Living Eggs of Rats and Mice with a Description of Apparatus for Obtaining and Observing Them. Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 1912, 9, 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus, G.; Enzmann, E.V. Can Mammalian Eggs Undergo Normal Development in Vitro? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1934, 20, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatenby, J.B. Some Notes on Recent Primate Embryology. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 1945, 20, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavister, B.D.; Boatman, D.E.; Leibfried, L.; Loose, M.; Vernon, M.W. Fertilization and Cleavage of Rhesus Monkey Oocytes in Vitro. Biol. Reprod. 1983, 28, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, J.; Menkin, M.F. In Vitro Fertilization and Cleavage of Human Ovarian Eggs. Science 1944, 100, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggers, J.D. IVF and Embryo Transfer: Historical Origin and Development. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2012, 25, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Taft, R.A. Virtues and Limitations of the Preimplantation Mouse Embryo as a Model System. Theriogenology 2008, 69, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotta, J. Die Befruchtung und Furchung des Eies der Maus. Arch. Mikr. Anat. 1895, 45, 15–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, J., Jr. Recovery and Culture of Tubal Mouse Ova. Nature 1947, 163, 28–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.; Rieger, D. Historical Background of Gamete and Embryo Culture. In Embryo Culture: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.D.; Takayama, S.; Swain, J.E. Rethinking in Vitro Embryo Culture: New Developments in Culture Platforms and Potential to Improve Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Biol. Reprod. 2012, 86, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedzhov, I.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Self-Organizing Properties of Mouse Pluripotent Cells Initiate Morphogenesis upon Implantation. Cell 2014, 156, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, T.; Zhang, H.T.; Panavaite, L.; Erzberger, A.; Fabrèges, D.; Snajder, R.; Wolny, A.; Korotkevich, E.; Tsuchida-Straeten, N.; Hufnagel, L.; et al. An Ex Vivo System to Study Cellular Dynamics Underlying Mouse Peri-Implantation Development. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogolyubova, I.; Stein, G.; Bogolyubov, D. FRET Analysis of Interactions Between Actin and Exon-Exon-Junction Complex Proteins in Early Mouse Embryos. Cell Tissue Res. 2013, 352, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Cohen, M.A.; Alsina, F.C.; Devlin, G.; Garrett, A.; McKey, J.; Havlik, P.; Rakhilin, N.; Wang, E.; Xiang, K.; et al. Intravital Imaging of Mouse Embryos. Science 2020, 368, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhai, J.; Wan, H.; Jiang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Xiang, Y.; He, X.; Zhao, Z.A.; Zhao, B.; et al. In Vitro Culture of Cynomolgus Monkey Embryos Beyond Early Gastrulation. Science 2019, 366, eaax7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppig, J.J.; Schultz, R.M.; O’Brien, M.; Chesnel, F. Relationship Between the Developmental Programs Controlling Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Maturation of Mouse Oocytes. Dev. Biol. 1994, 164, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, M.O.; Wright, S.J. Distinct Subtypes of Zona Pellucida Morphology Reflect Canine Oocyte Viability and Cumulus-Oocyte Complex Quality. Theriogenology 2013, 80, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maro, B.; Kubiak, J.; Gueth, C.; De Pennart, H.; Houliston, E.; Weber, M.; Antony, C.; Aghion, J. Cytoskeleton Organization During Oogenesis, Fertilization and Preimplantation Development of the Mouse. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1990, 34, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, S.C.; Surani, M.A.; Norris, M.L. Role of Paternal and Maternal Genomes in Mouse Development. Nature 1984, 311, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLay, D.W.; Clarke, H.J. Remodelling the Paternal Chromatin at Fertilization in Mammals. Reproduction 2003, 125, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassler, J.; Brandão, H.B.; Imakaev, M.; Flyamer, I.M.; Ladstätter, S.; Bickmore, W.A.; Peters, J.M.; Mirny, L.A.; Tachibana, K. A Mechanism of Cohesin-Dependent Loop Extrusion Organizes Zygotic Genome Architecture. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 3600–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asami, M.; Lam, B.Y.H.; Hoffmann, M.; Suzuki, T.; Lu, X.; Yoshida, N.; Ma, M.K.; Rainbow, K.; Gužvić, M.; VerMilyea, M.D.; et al. A Program of Successive Gene Expression in Mouse One-Cell Embryos. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffler, K.; Uraji, J.; Jentoft, I.; Harasimov, K.; Stützer, A.; Srayko, M.; Mörgelin, M.; Tischer, C.; Blanchard, M.M. Two Mechanisms Drive Pronuclear Migration in Mouse Zygotes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calarco, P.G.; Brown, E.H. An Ultrastructural and Cytological Study of Preimplantation Development of the Mouse. J. Exp. Zool. 1969, 171, 253–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducibella, T.; Anderson, E. Cell Shape and Membrane Changes in the Eight-Cell Mouse Embryo: Prerequisites for Morphogenesis of the Blastocyst. Dev. Biol. 1975, 47, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leivo, I.; Vaheri, A.; Timpl, R.; Wartiovaara, J. Appearance and Distribution of Collagens and Laminin in the Early Mouse Embryo. Dev. Biol. 1980, 76, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R.O.; Yamanaka, Y.; Rossant, J. Disorganized Epithelial Polarity and Excess Trophectoderm Cell Fate in Preimplantation Embryos Lacking E-Cadherin. Development 2010, 137, 3383–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maître, J.L.; Niwayama, R.; Turlier, H.; Nédélec, F.; Hiiragi, T. Pulsatile Cell-Autonomous Contractility Drives Compaction in the Mouse Embryo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro-González, J.C.; White, M.D.; Silva, J.C.; Plachta, N. Cadherin-Dependent Filopodia Control Preimplantation Embryo Compaction. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenker, J.; White, M.D.; Templin, R.M.; Parton, R.G.; Thorn-Seshold, O.; Bissiere, S.; Plachta, N. A Microtubule-Organizing Center Directing Intracellular Transport in the Early Mouse Embryo. Science 2017, 357, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, Y.; Ralston, A.; Stephenson, R.O.; Rossant, J. Cell and Molecular Regulation of the Mouse Blastocyst. Dev. Dyn. 2006, 235, 2301–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Cornwall-Scoones, J.; Wang, P.; Handford, C.E.; Na, J.; Thomson, M.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Developmental Clock and Mechanism of De Novo Polarization of the Mouse Embryo. Science 2020, 370, eabd2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Leung, C.Y.; Shahbazi, M.N.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Actomyosin Polarisation Through PLC-PKC Triggers Symmetry Breaking of the Mouse Embryo. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirate, Y.; Hirahara, S.; Inoue, K.; Suzuki, A.; Alarcon, V.B.; Akimoto, K.; Hirai, T.; Hara, T.; Adachi, M.; Chida, K.; et al. Polarity-Dependent Distribution of Angiomotin Localizes Hippo Signaling in Preimplantation Embryos. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 1181–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kono, K.; Tamashiro, D.A.; Alarcon, V.B. Inhibition of RHO-ROCK Signaling Enhances ICM and Suppresses TE Characteristics Through Activation of Hippo Signaling in the Mouse Blastocyst. Dev. Biol. 2014, 394, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, V.B.; Marikawa, Y. ROCK and RHO Playlist for Preimplantation Development: Streaming to HIPPO Pathway and Apicobasal Polarity in the First Cell Differentiation. In Advances in Anatomy, Embryology and Cell Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 229, pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wu, Z.; Shi, X.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Ye, X.; Liu, L.; Na, J.; Cheng, H.; et al. Atypical PKC, Regulated by Rho GTPases and Mek/Erk, Phosphorylates Ezrin During Eight-Cell Embryo Compaction. Dev. Biol. 2013, 375, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Building an Apical Domain in the Early Mouse Embryo: Lessons, Challenges and Perspectives. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020, 62, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maître, J.L.; Turlier, H.; Illukkumbura, R.; Eismann, B.; Niwayama, R.; Nédélec, F.; Hiiragi, T. Asymmetric Division of Contractile Domains Couples Cell Positioning and Fate Specification. Nature 2016, 536, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrode, N.; Xenopoulos, P.; Piliszek, A.; Frankenberg, S.; Plusa, B.; Hadjantonakis, A.K. Anatomy of a Blastocyst: Cell Behaviors Driving Cell Fate Choice and Morphogenesis in the Early Mouse Embryo. Genesis 2013, 51, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, T.P. A Quantitative Analysis of Cell Allocation to Trophectoderm and Inner Cell Mass in the Mouse Blastocyst. Dev. Biol. 1987, 119, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyooka, Y.; Oka, S.; Fujimori, T. Early Preimplantation Cells Expressing Cdx2 Exhibit Plasticity of Specification to TE and ICM Lineages Through Positional Changes. Dev. Biol. 2016, 411, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindle, A.I. Cell Allocation in Preimplantation Mouse Chimeras. J. Exp. Zool. 1982, 219, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plusa, B.; Frankenberg, S.; Chalmers, A.; Hadjantonakis, A.K.; Moore, C.A.; Papalopulu, N.; Papaioannou, V.E.; Glover, D.M.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Downregulation of Par3 and aPKC Function Directs Cells Towards the ICM in the Preimplantation Mouse Embryo. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilhac, S.M.; Adams, R.J.; Morris, S.A.; Danckaert, A.; Le Garrec, J.F.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Active Cell Movements Coupled to Positional Induction Are Involved in Lineage Segregation in the Mouse Blastocyst. Dev. Biol. 2009, 331, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anani, S.; Bhat, S.; Honma-Yamanaka, N.; Krawchuk, D.; Yamanaka, Y. Initiation of Hippo Signaling is Linked to Polarity Rather Than to Cell Position in the Pre-Implantation Mouse Embryo. Development 2014, 141, 2813–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chazaud, C.; Yamanaka, Y. Lineage Specification in the Mouse Preimplantation Embryo. Development 2016, 143, 1063–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiley, L.M.; Eglitis, M.A. Effects of Colcemid on Cavitation During Mouse Blastocoele Formation. Exp. Cell Res. 1980, 127, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, A. Observations upon the Development of the Segmentation Cavity, the Archenteron, the Germinal Layers, and the Amnion in Mammals. J. Cell Sci. 1892, s2-33, 369–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcroft, L.C.; Offenberg, H.; Thomsen, P.; Watson, A.J. Aquaporin Proteins in Murine Trophectoderm Mediate Transepithelial Water Movements During Cavitation. Dev. Biol. 2003, 256, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiley, L.M. Cavitation in the Mouse Preimplantation Embryo: Na/K-ATPase and the Origin of Nascent Blastocoele Fluid. Dev. Biol. 1984, 105, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mau, K.H.T.; Karimlou, D.; Barneda, D.; Brochard, V.; Royer, C.; Leeke, B.; de Souza, R.A.; Pailles, M.; Percharde, M.; Srinivas, S.; et al. Dynamic Enlargement and Mobilization of Lipid Droplets in Pluripotent Cells Coordinate Morphogenesis During Mouse Peri-Implantation Development. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriwaki, K.; Tsukita, S.; Furuse, M. Tight Junctions Containing Claudin 4 and 6 are Essential for Blastocyst Formation in Preimplantation Mouse Embryos. Dev. Biol. 2007, 312, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, J.; White, M.D.; Gasnier, M.; Alvarez, Y.D.; Lim, H.Y.G.; Bissiere, S.; Plachta, N. Expanding Actin Rings Zipper the Mouse Embryo for Blastocyst Formation. Cell 2018, 173, 776–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manejwala, F.; Kaji, E.; Schultz, R.M. Development of Activatable Adenylate Cyclase in the Preimplantation Mouse Embryo and a Role for Cyclic AMP in Blastocoel Formation. Cell 1986, 46, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manejwala, F.M.; Cragoe, E.J., Jr.; Schultz, R.M. Blastocoel Expansion in the Preimplantation Mouse Embryo: Role of Extracellular Sodium and Chloride and Possible Apical Routes of Their Entry. Dev. Biol. 1989, 133, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.J.; Costanzo, M.; Ruiz-Herrero, T.; Mönke, G.; Petrie, R.J.; Bergert, M.; Diz-Muñoz, A.; Mahadevan, L.; Hiiragi, T. Hydraulic Control of Mammalian Embryo Size and Cell Fate. Nature 2019, 571, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.Q.; Chan, C.J.; Graner, F.; Hiiragi, T. Lumen Expansion Facilitates Epiblast-Primitive Endoderm Fate Specification During Mouse Blastocyst Formation. Dev. Cell 2019, 51, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaoka, K.; Hamada, H. Cell Fate Decisions and Axis Determination in the Early Mouse Embryo. Development 2012, 139, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.J.; Robertson, E.J. Making a Commitment: Cell Lineage Allocation and Axis Patterning in the Early Mouse Embryo. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.F.; Deussen, Z.A. Features of Cell Lineage in Preimplantation Mouse Development. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1978, 48, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strumpf, D.; Mao, C.A.; Yamanaka, Y.; Ralston, A.; Chawengsaksophak, K.; Beck, F.; Rossant, J. Cdx2 is Required for Correct Cell Fate Specification and Differentiation of Trophectoderm in the Mouse Blastocyst. Development 2005, 132, 2093–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, A.; Rossant, J. Cdx2 Acts Downstream of Cell Polarization to Cell-Autonomously Promote Trophectoderm Fate in the Early Mouse Embryo. Dev. Biol. 2008, 313, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz, N.; Plusa, B. Early Cell Fate Decisions in the Mouse Embryo. Reproduction 2013, 145, R65–R80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artus, J.; Piliszek, A.; Hadjantonakis, A.K. The Primitive Endoderm Lineage of the Mouse Blastocyst: Sequential Transcription Factor Activation and Regulation of Differentiation by Sox17. Dev. Biol. 2011, 350, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, R.A. Control of the Embryonic Stem Cell State. Cell 2011, 144, 940–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avilion, A.A.; Nicolis, S.K.; Pevny, L.H.; Perez, L.; Vivian, N.; Lovell-Badge, R. Multipotent Cell Lineages in Early Mouse Development Depend on SOX2 Function. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarkowski, A.K.; Wróblewska, J. Development of Blastomeres of Mouse Eggs Isolated at the 4- and 8-Cell Stage. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1967, 18, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimber, S.J.; Surani, M.A.; Barton, S.C. Interactions of blastomeres suggest changes in cell surface adhesiveness during the formation of inner cell mass and trophectoderm in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Development 1982, 70, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.J. Studies of the Developmental Potential of 4- and 8-Cell Stage Mouse Blastomeres. J. Exp. Zool. 1977, 200, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwińska, A.; Czołowska, R.; Ozdzeński, W.; Tarkowski, A.K. Blastomeres of the Mouse Embryo Lose Totipotency After the Fifth Cleavage Division: Expression of Cdx2 and Oct4 and Developmental Potential of Inner and Outer Blastomeres of 16- and 32-Cell Embryos. Dev. Biol. 2008, 322, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.H.; Ziomek, C.A. Induction of Polarity in Mouse 8-Cell Blastomeres: Specificity, Geometry, and Stability. J. Cell Biol. 1981, 91, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.H.; Ziomek, C.A. The Foundation of Two Distinct Cell Lineages Within the Mouse Morula. Cell 1981, 24, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.H.; McConnell, J.M. Lineage Allocation and Cell Polarity During Mouse Embryogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004, 15, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H. Position- and Polarity-Dependent Hippo Signaling Regulates Cell Fates in Preimplantation Mouse Embryos. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 47-48, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlović, A.I.; Bruce, A.W. The First Cell-Fate Decision of Mouse Preimplantation Embryo Development: Integrating Cell Position and Polarity. Open Biol. 2017, 7, 170210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwayama, R.; Moghe, P.; Liu, Y.J.; Fabrèges, D.; Buchholz, F.; Piel, M.; Hiiragi, T. A Tug-of-War Between Cell Shape and Polarity Controls Division Orientation to Ensure Robust Patterning in the Mouse Blastocyst. Dev. Cell 2019, 51, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.L.; Rossant, J. Investigation of the Fate of 4-5 Day Post-Coitum Mouse Inner Cell Mass Cells by Blastocyst Injection. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1979, 52, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Plusa, B.; Piliszek, A.; Frankenberg, S.; Artus, J.; Hadjantonakis, A.K. Distinct Sequential Cell Behaviours Direct Primitive Endoderm Formation in the Mouse Blastocyst. Development 2008, 135, 3081–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chazaud, C.; Yamanaka, Y.; Pawson, T.; Rossant, J. Early Lineage Segregation Between Epiblast and Primitive Endoderm in Mouse Blastocysts Through the Grb2-MAPK Pathway. Dev. Cell 2006, 10, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberg, S.; Gerbe, F.; Bessonnard, S.; Belville, C.; Pouchin, P.; Bardot, O.; Chazaud, C. Primitive Endoderm Differentiates via a Three-Step Mechanism Involving Nanog and RTK Signaling. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.A.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Formation of Distinct Cell Types in the Mouse Blastocyst. In Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 55, pp. 203–217. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Garg, V.; Hadjantonakis, A.K. Lineage Establishment and Progression Within the Inner Cell Mass of the Mouse Blastocyst Requires FGFR1 and FGFR2. Dev. Cell 2017, 41, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, S.C.; Corujo-Simón, E.; Lilao-Garzón, J.; Stelzer, E.H.K.; Muñoz-Descalzo, S. Three-Dimensional Cell Neighbourhood Impacts Differentiation in the Inner Mass Cells of the Mouse Blastocyst. bioRxiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebisch, T.; Drusko, A.; Mathew, B.; Stelzer, E.H.K.; Fischer, S.C.; Matthäus, F. Cell Fate Clusters in ICM Organoids Arise from Cell Fate Heredity and Division: A Modelling Approach. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, B.; Muñoz-Descalzo, S.; Corujo-Simon, E.; Schröter, C.; Stelzer, E.H.K.; Fischer, S.C. Mouse ICM Organoids Reveal Three-Dimensional Cell Fate Clustering. Biophys. J. 2019, 116, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.C.; Corujo-Simon, E.; Lilao-Garzon, J.; Stelzer, E.H.K.; Muñoz-Descalzo, S. The Transition from Local to Global Patterns Governs the Differentiation of Mouse Blastocysts. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalcq, A.M. Sur la terminologie de l’induction [Terminology of induction]. Acta Anat. 1957, 30, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, R.L. Specification of Embryonic Axes Begins Before Cleavage in Normal Mouse Development. Development 2001, 128, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, K.; Wianny, F.; Pedersen, R.A.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Blastomeres Arising from the First Cleavage Division Have Distinguishable Fates in Normal Mouse Development. Development 2001, 128, 3739–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska-Nitsche, K.; Perea-Gomez, A.; Haraguchi, S.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Four-Cell Stage Mouse Blastomeres Have Different Developmental Properties. Development 2005, 132, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plachta, N.; Bollenbach, T.; Pease, S.; Fraser, S.E.; Pantazis, P. Oct4 Kinetics Predict Cell Lineage Patterning in the Early Mammalian Embryo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, J.; Tang, F.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Duan, E. Dynamic Transcriptional Symmetry-Breaking in Pre-Implantation Mammalian Embryo Development Revealed by Single-Cell RNA-Seq. Development 2015, 142, 3468–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.L. Flow of Cells from Polar to Mural Trophectoderm is Polarized in the Mouse Blastocyst. Hum. Reprod. 2000, 15, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, N.; Weberling, A.; Strathdee, D.; Anderson, K.I.; Timpson, P.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Morphogenesis of Extra-Embryonic Tissues Directs the Remodelling of the Mouse Embryo at Implantation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.; Feldberg, D. Effects of the Size and Number of Zona Pellucida Openings on Hatching and Trophoblast Outgrowth in the Mouse Embryo. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1991, 30, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perona, R.M.; Wassarman, P.M. Mouse Blastocysts Hatch in Vitro by Using a Trypsin-Like Proteinase Associated with Cells of Mural Trophectoderm. Dev. Biol. 1986, 114, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, C.M.; Liu, S.Y.; Karpinka, J.B.; Rancourt, D.E. Embryonic Hatching Enzyme Strypsin/ISP1 is Expressed with ISP2 in Endometrial Glands During Implantation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2002, 62, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.B.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, Y.B.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Suh, C.S.; Kim, S.H.; Lim, H.J. The Effect of Various Assisted Hatching Techniques on the Mouse Early Embryo Development. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2014, 41, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ilina, I.V.; Khramova, Y.V.; Ivanova, A.D.; Filatov, M.A.; Silaeva, Y.Y.; Deykin, A.V.; Sitnikov, D.S. Controlled Hatching at the Prescribed Site Using Femtosecond Laser for Zona Pellucida Drilling at the Early Blastocyst Stage. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2021, 38, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Dai, Y.; Presicce, G.A.; Du, F. Site Specificity of Blastocyst Hatching Significantly Influences Pregnancy Outcomes in Mice. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Teng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ma, M.; Li, M.; Peng, X.; Liu, C. Gene Expression Changes in Blastocyst Hatching Affect Embryo Implantation Success in Mice. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1496298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonavicius, K.; Royer, C.; Preece, C.; Davies, B.; Biggins, J.S.; Srinivas, S. Mechanics of Mouse Blastocyst Hatching Revealed by a Hydrogel-Based Microdeformation Assay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 10375–10380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, M.; Gardner, D.K. Nonessential Amino Acids and Glutamine Decrease the Time of the First Three Cleavage Divisions and Increase Compaction of Mouse Zygotes in Vitro. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 1997, 14, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.; Hooper, K.; Gardner, D.K. Effect of Essential Amino Acids on Mouse Embryo Viability and Ammonium Production. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2001, 18, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Scarrow, M.; Lawson, J.; Kinzer, D.; Goldfarb, J. Evaluation of the Effect of Interleukin-6 and Human Extracellullar Matrix on Embryonic Development. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 14, 1588–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kim, Y.S.; Fan, R.; Kremer, L.; Kuempel-Rink, N.; Mildner, K.; Zeuschner, D.; Hekking, L.; Stehling, M.; Bedzhov, I. Deciphering Epiblast Lumenogenesis Reveals Proamniotic Cavity Control of Embryo Growth and Patterning. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Chen, J.; He, Y.; Luo, H.; Yuan, H.; Chen, L.; Huang, L.; Mao, F.; Hu, S.; Qian, Y.; et al. Neddylation Inhibition Causes Impaired Mouse Embryo Quality and Blastocyst Hatching Failure Through Elevated Oxidative Stress and Reduced IL-1β. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 925702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, L.M.; Pedersen, R.A. Morphology of Mouse Egg Cylinder Development in Vitro: A Light and Electron Microscopic Study. J. Exp. Zool. 1977, 200, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vićovac, L.; Aplin, J.D. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition During Trophoblast Differentiation. Acta Anat. 1996, 156, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Helvert, S.; Storm, C.; Friedl, P. Mechanoreciprocity in Cell Migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, A.C.; Given, R.L.; Schlafke, S. Differentiation and Migration of Endoderm in the Rat and Mouse at Implantation. Anat. Rec. 1978, 190, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltmaat, J.M.; Orelio, C.C.; van Oostwaard, D.W.J.; Van Rooijen, M.A.; Mummery, C.L.; Defize, L.H. Snail is an Immediate Early Target Gene of Parathyroid Hormone Related Peptide Signaling in Parietal Endoderm Formation. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2000, 44, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hogan, B.L.; Tilly, R. Cell interactions and endoderm differentiation in cultured mouse embryos. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1981, 62, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, R.H.; Spindle, A.I.; Pedersen, R.A. Mouse Embryo Attachment to Substratum and Interaction of Trophoblast with Cultured Cells. J. Exp. Zool. 1979, 208, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.E.; Potter, S.W.; Buckley, P.M. Mouse Embryos and Uterine Epithelia Show Adhesive Interactions in Culture. J. Exp. Zool. 1982, 222, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Vidal, E.; Lomelí, H. Imaging Filopodia Dynamics in the Mouse Blastocyst. Dev. Biol. 2004, 265, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, V.; Nikolaev, M.; Kromm, D.; Meister, M.; Toda, S.; Peters, A.; Kuckenberg, P.; Kranz, A.; Seiffe, A.; Schorle, H.; et al. Embryo-Uterine Interaction Coordinates Mouse Embryogenesis During Implantation. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e113280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Qiu, X.; Ma, Y.; Xu, W.; Chen, S.; Zhang, P.; Liu, M.; Lin, X. KRT18 Regulates Trophoblast Cell Migration and Invasion Which are Essential for Embryo Implantation. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2023, 21, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñailillo, R.; Velásquez, V.; Acuña-Gallardo, S.; García, F.; Sánchez, M.; Nardocci, G.; Illanes, S.E.; Monteiro, L.J. FOXM1 Participates in Trophoblast Migration and Early Trophoblast Invasion: Potential Role in Blastocyst Implantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oghbaei, F.; Zarezadeh, R.; Jafari-Gharabaghlou, D.; Ranjbar, M.; Nouri, M.; Fattahi, A.; Imakawa, K. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Process During Embryo Implantation. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 388, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallingford, M.C.; Angelo, J.R.; Mager, J. Morphogenetic Analysis of Peri-Implantation Development. Dev. Dyn. 2013, 242, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, E.M.A.F.; Abrahamsohn, P.A. Trophoblast Invasion During Implantation of the Mouse Embryo. Arch. Biol. Med. Exp. 1989, 22, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rassoulzadegan, M.; Rosen, B.S.; Gillot, I.; Cuzin, F. Phagocytosis Reveals a Reversible Differentiated State Early in the Development of the Mouse Embryo. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 3295–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, N.; Kyprianou, C.; Weberling, A.; Wang, R.; Cui, G.; Peng, G.; Jing, N.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Sequential Formation and Resolution of Multiple Rosettes Drive Embryo Remodelling After Implantation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 1278–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perea-Gomez, A.; Meilhac, S.M.; Piotrowska-Nitsche, K.; Gray, D.; Collignon, J.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Regionalization of the Mouse Visceral Endoderm as the Blastocyst Transforms into the Egg Cylinder. BMC Dev. Biol. 2007, 7, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, A.J. Interaction Between Inner Cell Mass and Trophectoderm of the Mouse Blastocyst. I. A Study of Cellular Proliferation. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1978, 48, 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bielinska, M.; Narita, N.; Wilson, D.B. Distinct Roles for Visceral Endoderm During Embryonic Mouse Development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1999, 43, 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi, H.; Uemura, M.; Hiramatsu, R.; Segami, S.; Pattarapanawan, M.; Hirate, Y.; Yoshimura, Y.; Hashimoto, H.; Higashiyama, H.; Sumitomo, H.; et al. Sox17 is Essential for Proper Formation of the Marginal Zone of Extraembryonic Endoderm Adjacent to a Developing Mouse Placental Disk. Biol. Reprod. 2018, 99, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, S.; Hadjantonakis, A.K. Journey of the Mouse Primitive Endoderm: From Specification to Maturation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 377, 20210252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coucouvanis, E.; Martin, G.R. BMP Signaling Plays a Role in Visceral Endoderm Differentiation and Cavitation in the Early Mouse Embryo. Development 1999, 126, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuykin, I.; Schulz, H.; Guan, K.; Bader, M. Activation of the PTHRP/Adenylate Cyclase Pathway Promotes Differentiation of Rat XEN Cells into Parietal Endoderm, Whereas Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Promotes Differentiation into Visceral Endoderm. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowski, A.; Molotkov, A.; Soriano, P. FGFR1 Regulates Trophectoderm Development and Facilitates Blastocyst Implantation. Dev. Biol. 2019, 446, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonica, F.; Orietti, L.C.; Mort, R.L.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Concerted Cell Divisions in Embryonic Visceral Endoderm Guide Anterior Visceral Endoderm Migration. Dev. Biol. 2019, 450, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, I.; Kimura-Yoshida, C.; Ueda, Y. Developmental and Mechanical Roles of Reichert’s Membrane in Mouse Embryos. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 377, 20210257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadas, R.; Rubinstein, H.; Mittnenzweig, M.; Mayshar, Y.; Ben-Yair, R.; Cheng, S.; Aguilera-Castrejon, A.; Reines, N.; Orenbuch, A.H.; Lifshitz, A.; et al. Temporal BMP4 Effects on Mouse Embryonic and Extraembryonic Development. Nature 2024, 634, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnison, M.; Broadhurst, R.; Pfeffer, P.L. Elf5 and Ets2 Maintain the Mouse Extraembryonic Ectoderm a Dosage Dependent Synergistic Manner. Dev. Biol. 2015, 397, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bi, S.; Huang, L.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Huang, B.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Dai, B.; et al. KAT8-Mediated H4K16ac is Essential for Sustaining Trophoblast Self-Renewal and Proliferation via Regulating CDX2. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, C.; Alexiou, M.; Cecena, G.; Verykokakis, M.; Bilitou, A.; Cross, J.C.; Oshima, R.G.; Mavrothalassitis, G. Transcriptional Repressor Erf Determines Extraembryonic Ectoderm Differentiation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 5201–5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, R.L.; Papaioannou, V.E.; Barton, S.C. Origin of the Ectoplacental Cone and Secondary Giant Cells in Mouse Blastocysts Reconstituted from Isolated Trophoblast and Inner Cell Mass. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1973, 30, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Chen, Y.; Ren, Y.; Yuan, P.; Wang, N.; Liu, Q.; Yang, C.; Yan, Z.; Yang, M.; Wang, J.; et al. Primary Specification of Blastocyst Trophectoderm by scRNA-seq: New Insights into Embryo Implantation. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabj3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.R.; Antonini, S.; Vianna-Morgante, A.M.; Machado-Santelli, G.M.; Bevilacqua, E. Developmental Changes in the Ploidy of Mouse Implanting Trophoblast Cells in Vitro. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2003, 119, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; de Bruin, A.; Saavedra, H.I.; Starovic, M.; Trimboli, A.; Yang, Y.; Opavska, J.; Wilson, P.; Thompson, J.C.; Ostrowski, M.C.; et al. Extra-Embryonic Function of Rb is Essential for Embryonic Development and Viability. Nature 2003, 421, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Gentile, L.; Fuchikami, T.; Sutter, J.; Psathaki, K.; Esteves, T.C.; Araúzo-Bravo, M.J.; Ortmeier, C.; Verberk, G.; Abe, K.; et al. Initiation of Trophectoderm Lineage Specification in Mouse Embryos is Independent of Cdx2. Development 2010, 137, 4159–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruane, P.T.; Tan, C.M.; Adlam, D.J.; Kimber, S.J.; Brison, D.R.; Aplin, J.D.; Westwood, M. Protein O-GlcNAcylation Promotes Trophoblast Differentiation at Implantation. Cells 2020, 9, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Antin, P.; Berx, G.; Blanpain, C.; Brabletz, T.; Bronner, M.; Campbell, K.; Cano, A.; Casanova, J.; Christofori, G.; et al. Guidelines and Definitions for Research on Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weberling, A.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Trophectoderm Mechanics Direct Epiblast Shape Upon Embryo Implantation. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrij, E.J.; Scholte op Reimer, Y.S.; Fuentes, L.R.; Guerreiro, I.M.; Holzmann, V.; Aldeguer, J.F.; Sestini, G.; Koo, B.K.; Kind, J.; van Blitterswijk, C.A.; et al. A Pendulum of Induction Between the Epiblast and Extra-Embryonic Endoderm Supports Post-Implantation Progression. Development 2022, 149, dev192310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesnard, D.; Donnison, M.; Fuerer, C.; Pfeffer, P.L.; Constam, D.B. The Microenvironment Patterns the Pluripotent Mouse Epiblast Through Paracrine Furin and Pace4 Proteolytic Activities. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 1871–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zwick, S.; Loew, E.; Grimley, J.S.; Ramanathan, S. Mouse Embryo Geometry Drives Formation of Robust Signaling Gradients Through Receptor Localization. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, S.; Heindryckx, B.; Van der Jeught, M.; Neupane, J.; O’Leary, T.; Lierman, S.; De Vos, W.H.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.; Deroo, T.; De Sutter, P. Inhibition of Transforming Growth Factor β Signaling Promotes Epiblast Formation in Mouse Embryos. Stem Cells Dev. 2015, 24, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Analysis | Cell Sorting Theory | Stage | Models Used | Main Methods | Unanswered Questions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models | ||||||

| Salt-pepper (Three steps) | Random sorting | 16-cell to 128-cell | Mouse embryo in vivo in vitro | Sectional imaging | How does each step happen? What happens between steps? | |

| Timing of internalisation | Set by division waves | 8-cell to 128-cell | Mouse embryo in vitro | Non-invasive cell tracking | How morula division sets cell fates in blastocyst | |

| Cell fate clustering | Community unity | Morula to blastocyst | ICM organoid Embryo in vivo | Sectional imaging Computation | Interaction mechanisms of cell distance, numbers &TFs | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, H. Spatiotemporal Frameworks of Morphogenesis and Cell Lineage Specification in Pre- and Peri-Implantation Mammalian Embryogenesis: Insights and Knowledge Gaps from Mouse Embryo. Biology 2025, 14, 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111596

Yang H. Spatiotemporal Frameworks of Morphogenesis and Cell Lineage Specification in Pre- and Peri-Implantation Mammalian Embryogenesis: Insights and Knowledge Gaps from Mouse Embryo. Biology. 2025; 14(11):1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111596

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Huanhuan. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Frameworks of Morphogenesis and Cell Lineage Specification in Pre- and Peri-Implantation Mammalian Embryogenesis: Insights and Knowledge Gaps from Mouse Embryo" Biology 14, no. 11: 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111596

APA StyleYang, H. (2025). Spatiotemporal Frameworks of Morphogenesis and Cell Lineage Specification in Pre- and Peri-Implantation Mammalian Embryogenesis: Insights and Knowledge Gaps from Mouse Embryo. Biology, 14(11), 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111596