Status and Analysis of Artificial Breeding and Management of Aquatic Turtles in China

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

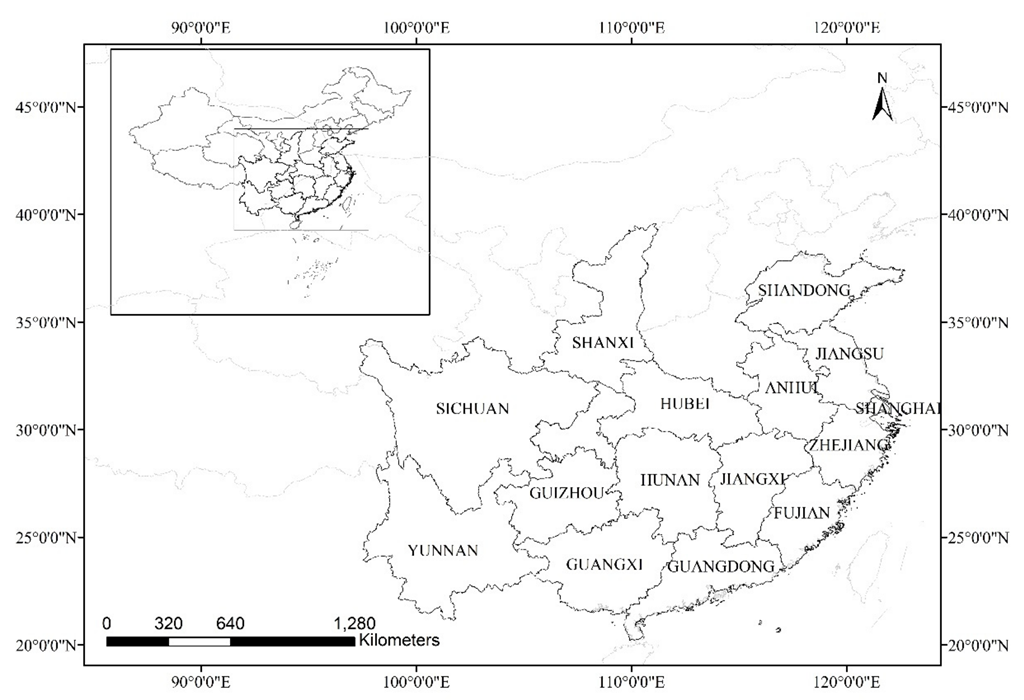

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Turtle Species

3.2. Certificate Status

3.3. Artificial Domestication and Breeding

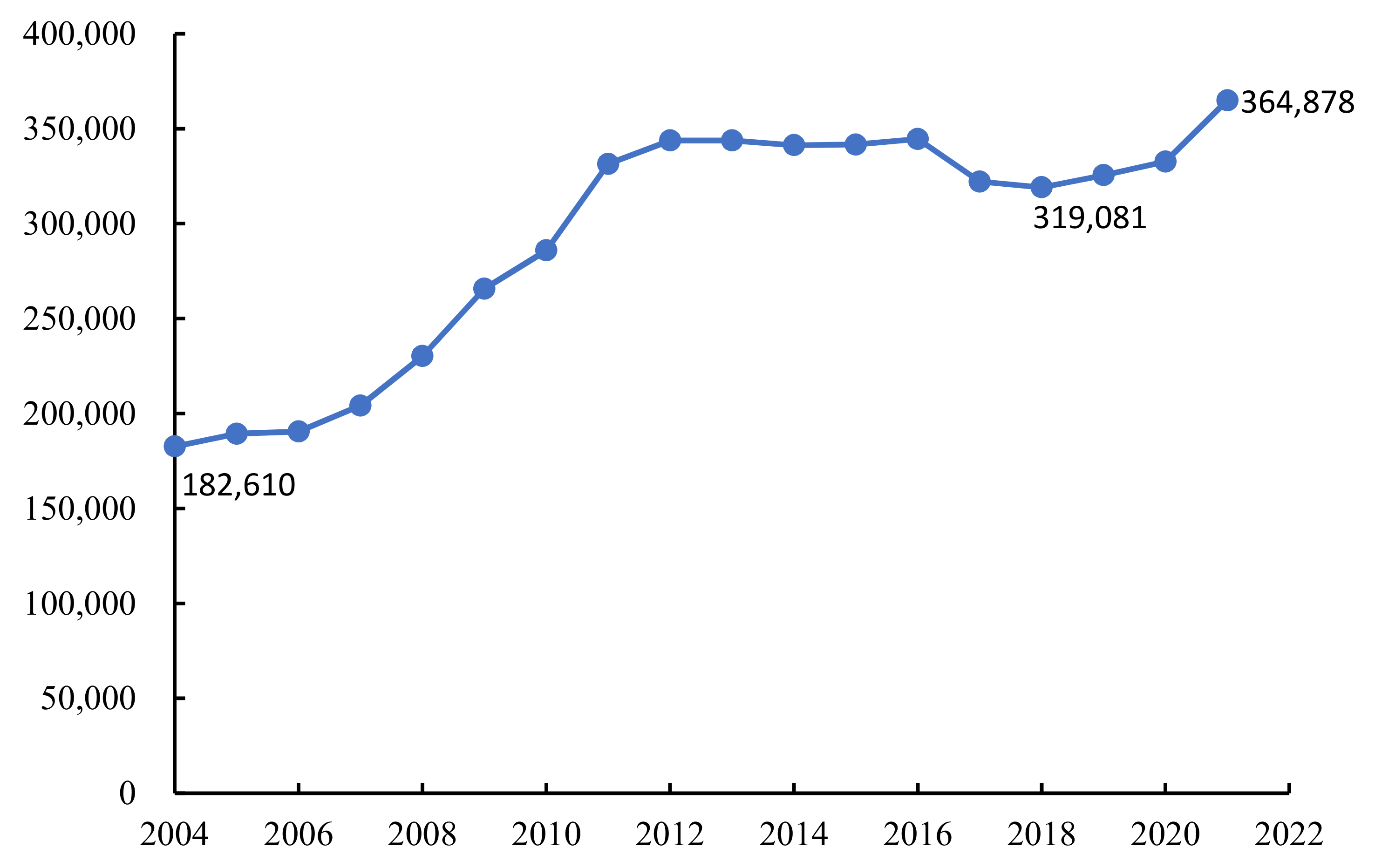

3.4. Turtle Production

4. Discussion

4.1. Data Reliability Analysis

4.2. Conservation Management Status

4.3. In Situ and Ex Situ Conservation

4.4. Management

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Families | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Podocnemididae | Erymnochelys | Erymnochelys madagascariensis |

| 2 | Peltocephalus | Peltocephalus dumeriliana | |

| 3 | Podocnemis | Podocnemis erythrocephala | |

| 4 | Podocnemis expansa | ||

| 5 | Podocnemis sextuberculata | ||

| 6 | Podocnemis unifilis | ||

| 7 | Chelidae | Acanthochelys | Acanthochelys macrocephala |

| 8 | Chelodina | Chelodina mccordi | |

| 9 | Macrodiremys | Macrodiremys oblonga | |

| 10 | Carettochelyidae | Carettochelys | Carettochelys insculpta |

| 11 | Cheloniidae | Caretta | Caretta caretta * |

| 12 | Chelonia | Chelonia mydas * | |

| 13 | Eretmochelys | Eretmochelys imbricata * | |

| 14 | Lepidochelys | Lepidochelys olivacea * | |

| 15 | Chelydridae | Chelydra | Chelydra serpentina |

| 16 | Macrochelys | Macrochelys temmincki | |

| 17 | Dermatemydidae | Dermatemys | Dermatemys mawii |

| 18 | Dermochelydidae | Dermochelys | Dermochelys coriacea * |

| 19 | Emydidae | Chrysemys | Chrysemys picta |

| 20 | Clemmys | Clemmys guttata | |

| 21 | Emydoidea | Emydoidea blandingii | |

| 22 | Emys | Emys orbicularis | |

| 23 | Glyptemys | Glyptemys insculpta | |

| 24 | Glyptemys muhlenbergii | ||

| 25 | Graptemys | Graptemys flavimaculata | |

| 26 | Graptemys nigrinoda | ||

| 27 | Malaclemys | Malaclemys terrapin | |

| 28 | Terrapene | Terrapene carolina | |

| 29 | Terrapene coahuila | ||

| 30 | Terrapene nelsoni | ||

| 31 | Terrapene ornata | ||

| 32 | Geoemydidae | Batagur | Batagur baska |

| 33 | Batagur borneoensis | ||

| 34 | Batagur dhongoka | ||

| 35 | Batagur kachuga | ||

| 36 | Batagur trivittata | ||

| 37 | Chinemys | Chinemys megalocephala * | |

| 38 | Chinemys nigricans * | ||

| 39 | Chinemys reevesii * | ||

| 40 | Cuora | Cuora amboinensis * | |

| 41 | Cuora aurocapitata * | ||

| 42 | Cuora flavomarginata * | ||

| 43 | Cuora galbinifrons * | ||

| 44 | Cuora mccordi * | ||

| 45 | Cuora mouhotii * | ||

| 46 | Cuora pani * | ||

| 47 | Cuora trifasciata * | ||

| 48 | Cuora yunnanensis * | ||

| 49 | Cuora zhoui * | ||

| 50 | Cyclemys | Cyclemys dentata * | |

| 51 | Cyclemys gemeli | ||

| 52 | Cyclemys oldhamii | ||

| 53 | Geoclemys | Geoclemys hamiltonii | |

| 54 | Geoemyda | Geoemyda spengleri * | |

| 55 | Heosemys | Heosemys depressa | |

| 56 | Heosemys grandis | ||

| 57 | Heosemys (Hieremys) annandalii | ||

| 58 | Malayemys | Malayemys subtrijuga | |

| 59 | Mauremys | Mauremys annamensis | |

| 60 | Mauremys japonica | ||

| 61 | Mauremys mutica * | ||

| 62 | Mauremys sinensis * | ||

| 63 | Melanochelys | Melanochelys trijuga | |

| 64 | Morenia | Morenia ocellata | |

| 65 | Morenia petersi | ||

| 66 | Notochelys | Notochelys platynota | |

| 67 | Pangshura | Pangshura tecta | |

| 68 | Sacalia | Sacalia bealei * | |

| 69 | Sacalia quadriocellata * | ||

| 70 | Siebenrockiella | Siebenrockeilla crassicollis | |

| 71 | Vijayachelys | Vijayachelys silvatica | |

| 72 | Kinosternidae | Kinosternon | Kinosternon leucostomum |

| 73 | Sternotherus | Sternotherus carinatus | |

| 74 | Sternotherus minor | ||

| 75 | Staurotypus | Staurotypus triporcatus | |

| 76 | Platysternidae | Platysternon | Platysternon megacephalum * |

| 77 | Trionychidae | Cyclanorbis | Cyclanorbis senegalensis |

| 78 | Cycloderma | Cycloderma aubryi | |

| 79 | Lissemys | Lissemys punctata | |

| 80 | Lissemys scutata | ||

| 81 | Amyda | Amyda cartilaginea | |

| 82 | Apalone | Apalone ferox | |

| 83 | Chitra | Chitra vandijki | |

| 84 | Palea | Palea steindachneri * | |

| 85 | Pelochelys | Pelochelys cantorii * | |

| 86 | Pelodiscus | Pelodiscus sinensis * | |

| 87 | Rafetus | Rafetus swinhoei * | |

| 88 | Trionyx | Trionyx triunguis |

References

- Ernst, C.H.; Barbour, R.W. Turtles of the World; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, MA, USA, 1989; Volume 272, pp. 1432–1521. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Li, P. Primary Color Drawing of Chinese Turtle Classification; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 31–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Wu, Y.; Rao, D.; Zhou, T.; Gong, S. China’s wild turtles at risk of extinction. Science 2020, 368, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisheries and Fisheries Administration of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs; National Fisheries Technology Promotion Station; China Fisheries Society. China Fisheries Statistical Yearbook; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2022. (In Chinese)

- Shi, H.; Fan, Z.; Yuan, Z. New data on the trade and captive breeding of turtles in Guangxi Province, South China. Asiat. Herpetol. Res. 2004, 10, 126–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, S.; Fu, Y.; Wang, J.; Shi, H.; Xu, N. Freshwater turtle trade in Hainan and suggestions for effective management. Biodivers. Sci. 2005, 13, 239–247. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, Z. Report of the State Council on the Research Regarding How to Deal with the Law-Enforcement Inspection Report on the Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on a Complete Ban of Illegal Wildlife Trade and the Elimination of the Unhealthy Habit of Indiscriminate Wild Animal Meat Consumption for the Protection of Human Life and Health and the Wildlife Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China and Its Deliberation Opinions; Bulletin of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021; Volume 3, pp. 626–631.

- Ren, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, X.; Hou, D.; Huang, H.; Li, C.; Rao, D.; Li, Y. Genomic insights into the evolution of the critically endangered soft-shelled turtle Rafetus swinhoei. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2022, 22, 1972–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Fang, Z.; Fang, Z. Study on biological property and rearing technique of Platuysternon megacephalum. China Fish. 2009, 5, 34–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Zhu, X.; Wei, C.; Du, H.; Chen, Y. Observation on the embryonic development of yellow pond turtle, Mauremys Mutica Cantor. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2008, 5, 649–656. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Z. Reports of Satellite Tracking Green Sea Turtles in China. Sichuan J. Zool. 2012, 31, 435–438. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hong, X.; Cai, X.; Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Zhao, J.; Qiu, Q.; Zhu, X. Conservation Status of the Asian Giant Softshell Turtle (Pelochelys cantorii) in China. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2019, 18, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Hong, X.; Zhao, J.; Liang, J.; Feng, Z. Reproduction of captive Asian giant softshell turtles, Pelochelys cantorii. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2015, 14, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, X.; Zhu, X.; Chen, C.; Zhao, J.; Ye, Z.; Qiu, Q. Reproduction traits of captive Asian giant softshell turtles, Pelochelys cantorii. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2018, 42, 794–799. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of People’s Republic China, Asian Giant Softshell Turtles, Pelochelys Cantorii Adaptive Protection Activities Held in Foshan, Guangdong. 2020; (In Chinese). Available online: http://www.cjyzbgs.moa.gov.cn/gzdt/202009/t20200928_6353394.htm (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of People’s Republic China, Remarkable Effect of Pelochelys Cantorii Wild Adaptation Protection. 2022; (In Chinese). Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/xw/bmdt/202205/t20220517_6399419.htm (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Rex, D. Mock turtles. Nature 2003, 423, 219–220. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, S.; Shi, H.; Jiang, A.; Fong, J.; Gaillard, D.; Wang, J. Disappearance of endangered turtles within China’s nature reserves. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 170–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Xiao, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, S. Survey on Turtle Trade in Huadiwan Market in Guangzhou. Chin. J. Zool. 2017, 52, 244–252. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Mcgarrity, M.E.; Bai, C.; Ke, Z.; Li, Y. Ecological knowledge reduces religious release of invasive species. Ecosphere 2013, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berec, M.; Klapka, V.; Zemek, R. Effect of an alien turtle predator on movement activity of European brown frog tadpoles. Ital. J. Zool. 2016, 83, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ríos, M.; Martín-Torrijos, L.; Diéguez-Uribeondo, J. The invasive alien red-eared slider turtle, Trachemys scripta, as a carrier of STEF-disease pathogens. Fungal Biol. 2022, 126, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, F. Alien Reptiles and Amphibians: A Scientific Compendium and Analysis; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 4, pp. 57–90. [Google Scholar]

| Families | Guangdong | Anhui | Fujian | Guangxi | Guizhou | Hubei | Hunan | Jiangsu | Jiangxi | Shangdong | Sichuan | Yunnan | Zhejiang | Shangxi | Shanghai |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Podocnemididae | 2/2 | 1/1 | 3/3 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 2/5 | ||||||||

| Chelidae | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | |||||||||||

| Carettochelyidae | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | ||||||||||||

| Cheloniidae | 4/4 | 2/2 | 3/3 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 2/2 | 3/3 | 3/3 | |||

| Chelydridae | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 1/1 | |||||||||

| Dermatemydidae | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | ||||||||||

| Dermochelydidae | 1/1 | ||||||||||||||

| Emydidae | 6/9 | 4/5 | 1/11 | 5/5 | 2/2 | 4/4 | 5/5 | 6/7 | 1/1 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 7/9 | |||

| Geoemydidae | 15/38 | 9/24 | 16/37 | 8/25 | 2/2 | 3/9 | 5/13 | 10/25 | 4/12 | 14/31 | 10/27 | 5/8 | 12/30 | 2/3 | |

| Kinosternidae | 2/4 | 2/3 | 1/1 | ||||||||||||

| Platysternidae | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | |||||

| Trionychidae | 7/7 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 6/6 | 1/1 | ||||||

| Total | 38/64 | 15/31 | 29/59 | 20/33 | 6/6 | 11/19 | 13/21 | 25/42 | 9/17 | 27/46 | 23/43 | 10/13 | 35/58 | 4/4 | 3/4 |

| Provinces/Municipalities | Total Number of Licensed Units | Number of Individual Captive Breeding License Holders | Number of Operating Permits Held Separately | Number of Certificate Holders with Two Certificates Held at the Same Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anhui | 74 | 25 | 1 | 48 |

| Fujian | 58 | 30 | 1 | 27 |

| Guangxi | 4280 | 14 | 31 | 4218 |

| Guizhou | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Hubei | 27 | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| Hunan | 13 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| Jiangsu | 116 | 28 | 3 | 85 |

| Jiangxi | 27 | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| Shandong | 100 | 3 | 1 | 96 |

| Shanxi | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Shanghai | 6 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Sichuan | 115 | 11 | 0 | 104 |

| Yunnan | 7 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Zhujiang | 207 | 68 | 13 | 126 |

| Guangdong | 23,820 | 16,821 | 435 | 6564 |

| Total | 28,861 | 17,007 | 489 | 11,348 |

| Families | Guangdong | Anhui | Fujian | Guangxi | Guizhou | Hubei | Hunan | Jiangsu | Jiangxi | Shangdong | Sichuan | Yunnan | Zhejiang | Shangxi | Shanghai |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Podocnemididae | 4 | 50 | 2710 | 1005 | 240 | 710 | 21,801 | ||||||||

| Chelidae | 1126 | 120 | 10 | 50 | |||||||||||

| Carettochelyidae | 9467 | 5790 | 25 | ||||||||||||

| Cheloniidae | 120 | 65 | 495 | 25 | 35 | 66 | 25 | 281 | 72 | 32 | 30 | 52 | |||

| Chelydridae | 16 | 250 | 25 | 50 | 520 | 2 | |||||||||

| Dermatemydidae | 31 | 110 | 20 | 20 | 50 | ||||||||||

| Dermochelydidae | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Emydidae | 160,960 | 684 | 12,210 | 10,453 | 30 | 855 | 92 | 740 | 6000 | 656 | 981 | 845 | |||

| Geoemydidae | 34,515,876 | 282,713 | 89,283 | 5,095,966 | 4025 | 82,449 | 2760 | 102,880 | 138,889 | 8727 | 40,823 | 2668 | 83,577 | 140 | |

| Kinosternidae | 485 | 280 | 35 | ||||||||||||

| Platysternidae | 10,270 | 1000 | 5471 | 170 | 5800 | 205 | 161 | 323 | 45 | ||||||

| Trionychidae | 116,304 | 290 | 1,041,577 | 100 | 300 | 323,074 | 5160 | 35,540 | 2 | ||||||

| Total | 34,814,129 | 283,478 | 111,578 | 6,154,967 | 4096 | 84,209 | 2912 | 104,086 | 150,764 | 10,444 | 365,891 | 8183 | 142,443 | 54 | 142 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, W.; Chen, F.; Zhu, X. Status and Analysis of Artificial Breeding and Management of Aquatic Turtles in China. Biology 2022, 11, 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11091368

Hong X, Zhang X, Liu X, Wang Y, Yu L, Li W, Chen F, Zhu X. Status and Analysis of Artificial Breeding and Management of Aquatic Turtles in China. Biology. 2022; 11(9):1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11091368

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Xiaoyou, Xiaoyan Zhang, Xiaoli Liu, Yakun Wang, Lingyun Yu, Wei Li, Fangcan Chen, and Xinping Zhu. 2022. "Status and Analysis of Artificial Breeding and Management of Aquatic Turtles in China" Biology 11, no. 9: 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11091368

APA StyleHong, X., Zhang, X., Liu, X., Wang, Y., Yu, L., Li, W., Chen, F., & Zhu, X. (2022). Status and Analysis of Artificial Breeding and Management of Aquatic Turtles in China. Biology, 11(9), 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11091368