The Effect of Intensive Dietary Intervention on the Level of RANTES and CXCL4 Chemokines in Patients with Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomised Study

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dietary Intervention

2.2. Physical Activity

2.3. Anthropometric Measurements

2.4. Biochemical Analyses

2.5. Calcium Score

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Inflammatory Marker Levels

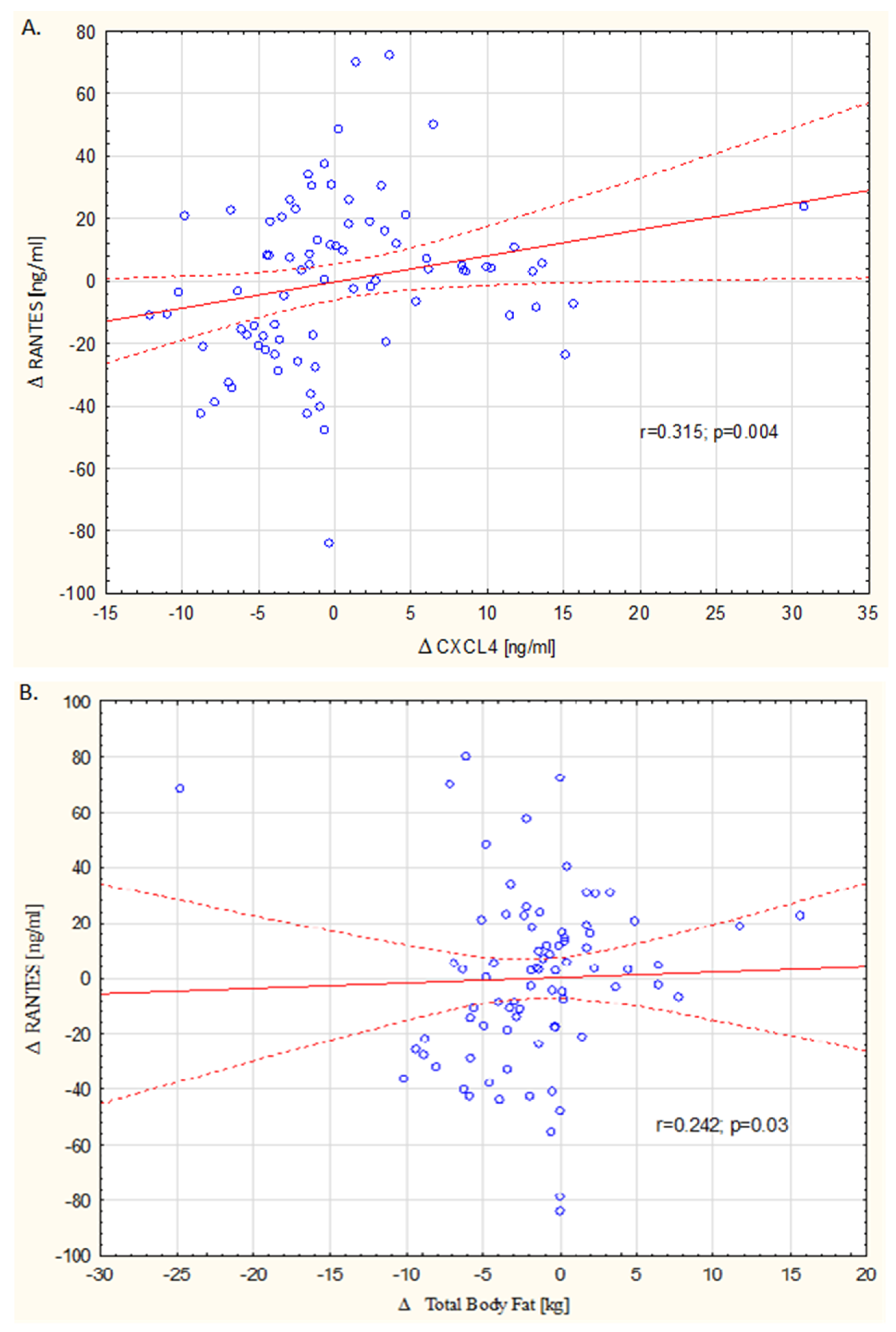

3.2. Correlation with DASH Index, Body Composition, Physical Activity and Calcium Score

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Appel, L.J.; Moore, T.J.; Obarzanek, E.; Vollmer, W.M.; Svetkey, L.P.; Sacks, F.M.; Bray, G.A.; Vogt, T.M.; Cutler, J.A.; Windhauser, M.M.; et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N. Engl. J Med. 1997, 336, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svetkey, L.P.; Simons-Morton, D.; Vollmer, W.M.; Appel, L.J.; Conlin, P.R.; Ryan, D.H.; Ard, J.; Kennedy, B.M. Effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure: Subgroup analysis of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) randomized clinical trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 159, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siervo, M.; Lara, J.; Chowdhury, S.; Ashor, A.; Oggioni, C.; Mathers, J.C. Effects of the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet on cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi-Abargouei, A.; Maghsoudi, Z.; Shirani, F.; Azadbakht, L. Effects of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-style diet on fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular diseases--incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis on observational prospective studies. Nutrition 2013, 29, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.C.; Wallin, A.; Wolk, A. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet and Incidence of Stroke: Results From 2 Prospective Cohorts. Stroke 2016, 47, 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Arablou, T.; Jayedi, A.; Salehi-Abargouei, A. Adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet in relation to all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, F.M.; Appel, L.J.; Moore, T.J.; Obarzanek, E.; Vollmer, W.M.; Svetkey, L.P.; Bray, G.A.; Vogt, T.M.; Cutler, J.A.; Windhauser, M.M.; et al. A dietary approach to prevent hypertension: A review of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Study. Clin. Cardiol. 1999, 22 (Suppl. S7), III6–III10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, S.; Chitsazi, M.J.; Salehi-Abargouei, A. The effect of dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) on serum inflammatory markers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhaei, R.; Shahvazi, S.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H.; Samadi, M.; Khatibi, N.; Nadjarzadeh, A.; Zare, F.; Salehi-Abargouei, A. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-Style Diet and an Alternative Mediterranean Diet are Differently Associated with Serum Inflammatory Markers in Female Adults. Food Nutr. Bull. 2018, 39, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 2002, 420, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakogiannis, C.; Sachse, M.; Stamatelopoulos, K.; Stellos, K. Platelet-derived chemokines in inflammation and atherosclerosis. Cytokine 2019, 122, 154157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattison, J.M.; Nelson, P.J.; Huie, P.; Sibley, R.K.; Krensky, A.M. RANTES chemokine expression in transplant-associated accelerated atherosclerosis. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 1996, 15, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Veillard, N.R.; Kwak, B.; Pelli, G.; Mulhaupt, F.; James, R.W.; Proudfoot, A.E.; Mach, F. Antagonism of RANTES receptors reduces atherosclerotic plaque formation in mice. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jia, Y.J.; Li, X.L.; Xu, R.X.; Zhu, C.G.; Guo, Y.L.; Wu, N.Q.; Li, J.J. RANTES gene G-403A polymorphism and coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE. 2012, 7, e47211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, S.; Uehata, S.; Saito, S.; Osumi, K.; Ozeki, Y.; Kimura, Y. Enzyme immunoassay detection of platelet-derived microparticles and RANTES in acute coronary syndrome. Thromb. Haemost. 2003, 89, 506–512. [Google Scholar]

- Parissis, J.T.; Adamopoulos, S.; Venetsanou, K.F.; Mentzikof, D.G.; Karas, S.M.; Kremastinos, D.T. Serum profiles of C-C chemokines in acute myocardial infarction: Possible implication in postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. J. Interferon. Cytokine Res. 2002, 22, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothenbacher, D.; Muller-Scholze, S.; Herder, C.; Koenig, W.; Kolb, H. Differential expression of chemokines, risk of stable coronary heart disease, and correlation with established cardiovascular risk markers. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueba, T.; Nomura, S.; Inami, N.; Yokoi, T.; Inoue, T. Elevated RANTES level is associated with metabolic syndrome and correlated with activated platelets associated markers in healthy younger men. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2014, 20, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavusoglu, E.; Eng, C.; Chopra, V.; Clark, L.T.; Pinsky, D.J.; Marmur, J.D. Low plasma RANTES levels are an independent predictor of cardiac mortality in patients referred for coronary angiography. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zernecke, A.; Shagdarsuren, E.; Weber, C. Chemokines in atherosclerosis: An update. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 1897–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajen, T.; Koenen, R.R.; Werner, I.; Staudt, M.; Projahn, D.; Curaj, A.; Sönmez, T.T.; Simsekyilmaz, S.; Schumacher, D.; Möllmann, J.; et al. Blocking CCL5-CXCL4 Heteromerization Preserves Heart Function After Myocardial Infarction by Attenuating Leukocyte Recruitment and NETosis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.P.; Lindenfeld, J.; Ellis, J.B.; Raymond, N.M.; Krentz, L.S. Increased plasma concentrations of platelet factor 4 in coronary artery disease: A measure of in vivo platelet activation and secretion. Circulation. 1981, 64, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbel, C.; Korosoglou, G.; Ler, P.; Akhavanpoor, M.; Domschke, G.; Linden, F.; Doesch, A.O.; Buss, S.J.; Giannitsis, E.; Katus, H.A.; et al. CXCL4 Plasma Levels Are Not Associated with the Extent of Coronary Artery Disease or with Coronary Plaque Morphology. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- von Hundelshausen, P.; Koenen, R.R.; Sack, M.; Mause, S.F.; Adriaens, W.; Proudfoot, A.E.; Hackeng, T.M.; Weber, C. Heterophilic interactions of platelet factor 4 and RANTES promote monocyte arrest on endothelium. Blood 2005, 105, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, R.; Urpi-Sardà, M.; Sacanella, E.; Arranz, S.; Corella, D.; Castañer, O.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lapetra, J.; Portillo, M.P.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of the Mediterranean Diet in the Early and Late Stages of Atheroma Plaque Development. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 3674390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalescot, G.; Sechtem, U.; Achenbach, S.; Andreotti, F.; Arden, C.; Budaj, A.; Bugiardini, R.; Crea, F.; Cuisset, T.; Di Mario, C.; et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: The Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2949–3003. [Google Scholar]

- Gunther, A.L.; Liese, A.D.; Bell, R.A.; Dabelea, D.; Lawrence, J.M.; Rodriguez, B.L.; Standiford, D.A.; Mayer-Davis, E.J. Association between the dietary approaches to hypertension diet and hypertension in youth with diabetes mellitus. Hypertension 2009, 53, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteylen, M.O.; Manca, M.; Joosen, I.A.; Schmidt, D.E.; Das, M.; Hofstra, L.; Crijns, H.J.; Biessen, E.A.; Kietselaer, B.L. CC chemokine ligands in patients presenting with stable chest pain: Association with atherosclerosis and future cardiovascular events. Neth. Hear. J. 2016, 24, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Virani, S.S.; Nambi, V.; Hoogeveen, R.; Wasserman, B.A.; Coresh, J.; Gonzalez, F., 2nd; Chambless, L.E.; Mosley, T.H.; Boerwinkle, E.; Ballantyne, C.M. Relationship between circulating levels of RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted) and carotid plaque characteristics: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Carotid MRI Study. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Ma, X.; Lyu, J.X.; Wang, C.; Du, X.Y.; Guan, Y.Q. Plasma RANTES level is correlated with cardio-cerebral atherosclerosis burden in patients with ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2020, 6, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podolec, J.; Kopec, G.; Niewiara, L.; Komar, M.; Guzik, B.; Bartus, K.; Tomkiewicz-Pajak, L.; Guzik, T.J.; Plazak, W.; Zmudka, K. Chemokine RANTES is increased at early stages of coronary artery disease. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 67, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Koper-Lenkiewicz, O.M.; Kamińska, J.; Lisowska, A.; Milewska, A.; Hirnle, T.; Dymicka-Piekarska, V. Factors Associated with RANTES Concentration in Cardiovascular Disease Patients. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 3026453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Caterina, R.; Gazzetti, P.; Mazzone, A.; Marzilli, M.; L’Abbate, A. Platelet activation in angina at rest. Evidence by paired measurement of plasma beta-thromboglobulin and platelet factor 4. Eur. Heart J. 1988, 9, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarewicz-Wujec, M.; Henzel, J.; Kruk, M.; Kępka, C.; Wardziak, Ł.; Trochimiuk, P.; Parzonko, A.; Demkow, M.; Kozłowska-Wojciechowska, M. DASH diet decreases CXCL4 plasma concentration in patients diagnosed with coronary atherosclerotic lesions. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenen, R.R.; von Hundelshausen, P.; Nesmelova, I.V.; Zernecke, A.; Liehn, E.A.; Sarabi, A.; Kramp, B.K.; Piccinini, A.M.; Paludan, S.R.; Kowalska, M.A.; et al. Disrupting functional interactions between platelet chemokines inhibits atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henzel, J.; Kępka, C.; Kruk, M.; Makarewicz-Wujec, M.; Wardziak, Ł.; Trochimiuk, P.; Dzielińska, Z.; Demkow, M. High-Risk Coronary Plaque Regression After Intensive Lifestyle Intervention in Nonbstructive Coronary Disease. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, T.R.; Wallace, E.L.; Macaulay, T.E.; Charnigo, R.J.; Evangelista, V.; Campbell, C.L.; Bailey, A.L.; Smyth, S.S. The effect of rosuvastatin on thromboinflammation in the setting of acute coronary syndrome. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2015, 39, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmoszyñska, A.; Kleinrok, A.; Dabrowski, P.; Sokoluk, I.; Markiewicz, M.; Ledwozyw, A.; Sokołowska, B. Effect of lovastatin on platelet function in hypercholesterolemic patients. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 1992, 88, 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- Cella, G.; Colby, S.I.; Taylor, A.D.; McCracken, L.; Parisi, A.F.; Sasahara, A.A. Platelet factor 4 (PF4) and heparin-released platelet factor 4 (HR-PF4) in patients with cardiovascular disorders. Thromb. Res. 1983, 29, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chacko, S.A. Dietary Mg intake and biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. In Magnesium in Human Health and Disease; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Moreno, C.; Cano, M.P.; de Ancos, B.; Plaza, L.; Olmedilla, B.; Granado, F.; Martin, A. High-pressurized orange juice consumption affects plasma vitamin C, antioxidative status and inflammatory markers in healthy humans. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 2204e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watzl, B.; Kulling, S.E.; Möseneder, J.; Barth, S.W.; Bub, A. A 4-wk intervention with high intake of carotenoid-rich vegetables and fruit reduces plasma C-reactive protein in healthy, nonsmoking men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 1052e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madani, R.; Karastergiou, K.; Ogston, N.C.; Miheisi, N.; Bhome, R.; Haloob, N.; Tan, G.D.; Karpe, F.; Malone-Lee, J.; Hashemi, M.; et al. RANTES release by human adipose tissue in vivo and evidence for depot-specific differences. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 296, E1262–E1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruzdeva, O.; Borodkina, D.; Uchasova, E.; Dyleva, Y.; Barbarash, O. Localization of fat depots and cardiovascular risk. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, A.V.; Chumakova, G.A.; Veselovskaya, N.G. Resistance to leptin in development of different obesity phenotypes. Russ. J. Cardiol. 2016, 4, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Clinical Data | Baseline | Follow-Up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASH Group (n = 40) | Control Group (n = 39) | p | DASH Group (n = 40) | Control Group (n = 39) | p | |

| Age (years) | 59.3 ± 8.14 | 60.5 ± 7.81 | 0.226 | |||

| Sex: men (%) | 27 (67) | 20 (51) | 0.261 | |||

| Observation time (weeks) | 69.4 ± 15.8 | 64.3 ± 10.7 | 0.08 | |||

| Hypercholesterolaemia, n (%) | 40 (100) | 38 (97) | 0.159 | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 38 (95) | 33 (85) | 0.50 | |||

| Impaired glucose tolerance, n (%) | 3 (7.5) | 3 (8) | 0.726 | |||

| Persistent atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 3 (7.5) | 3 (8) | 0.938 | |||

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | 0.851 | |||

| Current smoking, n (%) | 4 (10) | 9 (23) | 0.245 | |||

| Prior smoking, n (%) | 25 (62) | 26 (67) | 0.995 | |||

| Weight (kg) | 84.4 ± 16.8 | 83.0 ± 15.56 | 0.330 | 81.6 ± 14.5 | 81.6 ± 15.9 | 0.487 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.6 ± 4.15 | 29.09 ± 3.84 | 0.250 | 28.6 ± 3.6 | 28.6 ± 3.9 | 0.431 |

| Maximal lumen diameter stenosis, % | 36.6 ± 11.90 | 37.7 ± 10.30 | 0.413 | 32.2 ± 10.3 | 39.0 ± 12.4 | 0.011 |

| Number of lesions >50% | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | >0.999 | 2 (5) | 6 (15) | 0.150 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 129.4 ± 11.97 | 129.4 ± 14.78 | 0.498 | 125.7 ± 13.6 | 128.2 ± 13.60 | 0.214 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 79.7 ± 6.58 | 80.3 ± 8.66 | 0.368 | 76.8 ± 9.30 | 78.23 ± 5.61 | 0.222 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| β-Blocker, n (%) | 21 (52.5) | 26 (67) | 0.115 | 22 (55) | 27 (69) | 0.338 |

| ACE inhibitor, ARB n (%) | 26 (65) | 30 (77) | 0.335 | 24 (60) | 29 (74) | 0.250 |

| Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | 13 (32) | 10 (25) | 0.703 | 12 (30) | 11 (28) | 0.703 |

| Diuretic, n (%) | 10 (25) | 16 (41) | 0.250 | 10 (25) | 17 (43) | 0.179 |

| Number of antihypertensive drugs | 1.8 ± 1.10 | 2.2 ± 1.31 | 0.090 | 1.7 ± 1.31 | 2.4 ± 1.28 | 0.046 |

| Statins, n (%) | 25 (62) | 29 (74) | 0.233 | 32 (80) | 33 (84) | 0.851 |

| High-intensity-dose statins#, n (%) | 7 (17.5) | 7 (18) | 0.996 | 9 (22.5) | 8 (20.5) | 0.851 |

| Other lipid-lowering drugs, n (%) | 3 (7.5) | 2 (5) | 0.859 | 2 (5) | 1 (2.5) | 0.856 |

| ASA, n (%) | 23 (57.5) | 24 (61) | 0.505 | 26 (65) | 29 (74) | 0.566 |

| NOAC, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | 0.851 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | 0.850 |

| Warfarin, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | 0.851 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | 0.851 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 5 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 0.338 | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 0.444 |

| Study Groups | Grains | Vegetables | Fruits | Dairy | Meat | Nuts | Fat | Sweets | DASH Index | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | Baseline | 5.30 | 4.65 | 4.18 | 5.75 | 4.53 | 0.95 | 5.90 | 3.40 | 34.65 | p = 0.138 |

| Follow-up | 5.45 | 5.15 | 4.43 | 6.23 | 5.18 | 1.75 | 6.23 | 3.73 | 38.13 | ||

| DASH group | Baseline | 5.35 | 4.65 | 4.15 | 7.60 | 4.38 | 0.80 | 5.85 | 3.30 | 34.33 | p = 0.0001 |

| Follow-up | 8.25 | 7.23 | 6.45 | 7.60 | 8.85 | 5.40 | 9.10 | 7.60 | 60.47 | ||

| Clinical and Laboratory Data | 1st Quartile n = 19 | 2nd Quartile n = 21 | 3rd Quartile n = 19 | 4th Quartile n = 20 | Correlation Coefficient with RANTES Levels | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAD risk factors | ||||||

| Age (years) | 60.6 | 61.7 | 57.9 | 59.2 | −0.179 | 0.110 |

| Sex: men (%) | 8 (42%) | 12 (57%) | 12 (63%) | 16 (80%) | −0.192 | 0.087 |

| Obesity (body mass index (BMI) >30), n (%) | 8 (42%) | 7 (33%) | 13 (68%) | 14 (70%) | 0.156 | 0.165 |

| Total body fat % | 34.2 ± 8.5 | 30.5 ± 7.0 | 34.6 ± 7.7 | 32.5 ± 9.2 | −0.034 | 0.780 |

| Visceral fat (cm2) | 110.00 ± 56.7 | 96.2 ± 35.1 | 111.5 ± 35.6 | 110.79 ± 40.1 | 0.088 | 0.434 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia n, (%) | 19 (100%) | 20 (95%) | 19 (100%) | 19 (95%) | −0.053 | 0.635 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 16 (84%) | 19 (90%) | 16 (84%) | 19 (95%) | 0.121 | 0.281 |

| Calcium score (Agatson units) | 144.81 ± 147.0 | 223.75 ± 217.1 | 118.5 ± 122.5 | 254.63 ± 125.2 | 0.037 | 0.746 |

| Smoking (current and prior), n (%) | 10 (52%) | 10 (47.6%) | 11 (58%) | 16 (80%) | 0.192 | 0.086 |

| Laboratory data | ||||||

| RANTES (ng/mL) | 14.31 ± 5.6 | 27.26 ± 5.6 | 48.14 ± 5.0 | 68.75 ± 16.0 | - | - |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 0.19 ± 0.19 | 0.21 ± 0.17 | 0.28 ± 0.32 | 0.18 ± 0.15 | 0.054 | 0.634 |

| CXCL4 (ng/mL) | 9.60 ± 3.3 | 11.69 ± 4.0 | 12.13 ± 3.7 | 12.95 ± 3.9 | 0.296 | 0.007 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 27.53 ± 15.2 | 26.33 ± 18.6 | 34.16 ± 17.9 | 28.10 ± 9.9 | 0.146 | 0.196 |

| GGTP (IU/L) | 40.21 ± 48.4 | 37.50 ± 41.6 | 34.16 ± 33.9 | 30.21 ± 15.2 | 0.097 | 0.398 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 199.08 ± 61.1 | 169.69 ± 36.1 | 171.35 ± 30.9 | 183.55 ± 40.1 | −0.006 | 0.950 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 61.35 ± 20.1 | 59.34 ± 13.9 | 55.07 ± 13.1 | 53.16 ± 11.2 | −0.165 | 0.141 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 121.43 ± 53.8 | 101.67 ± 31.6 | 101.16 ± 29.9 | 110.18 ± 30.5 | −0.014 | 0.899 |

| Homocysteine (µmol/L) | 15.57 ± 12.2 | 14.35 ± 4.8 | 12.37 ± 3.0 | 11.66 ± 3.3 | −0.247 | 0.027 |

| Biochemical Parameters | Study Groups | Baseline | 6 Months Follow-Up | 12 Months Follow-Up | Change (Δ) | p-Value | p * Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | DASH group | 184.48 ± 44.8 | 169.43 ± 37.8 | 162.02 ± 35.1 | 22.46 ± 35.6 | 0.007 | 0.096 |

| Control | 175.07 ± 43.8 | 169.11 ± 36.8 | 164.54 ± 32.4 | 10.53 ± 44.7 | 0.115 | ||

| LDL, mg/dL | DASH group | 110.30 ± 36.3 | 98.54 ± 34.3 | 92.40 ± 29.1 | 17.89 ± 33.6 | 0.008 | 0.144 |

| Control | 106.83 ± 40.6 | 100.57 ± 34.1 | 98.08 ± 27.1 | −8.76 ± 42.0 | 0.133 | ||

| HDL, mg/dL | DASH group | 56.31 ± 15.4 | 60.58 ± 15.7 | 59.78 ± 14.5 | 3.46 ± 7.6 | 0.151 | 0.158 |

| Control | 58.48 ± 14.2 | 59.98 ± 15.8 | 60.17 ± 15.8 | 1.69 ± 8.1 | 0.311 | ||

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | DASH group | 73.21 ± 49.4 | 83.19 ± 50.25 | 95.06 ± 46.4 | 21.84 ± 50.8 | 0.022 | 0.023 |

| Control | 111.83 ± 66.5 | 111.8 ± 50.06 | 102.71 ± 41.8 | −9.12 ± 82.4 | 0.235 | ||

| hsCRP, mg/L | DASH group | 0.23 ± 0.2 | 0.15 ± 0.15 | 0.11 ± 0.1 | −0.12 ± 0.2 | 0.003 | 0.07 |

| Control | 0.19 ± 0.8 | 0.17 ± 0.12 | 0.26 ± 0.8 | 0.07 ± 0.78 | 0.295 | ||

| Homocysteine, umol/L | DASH group | 12.87 ± 4.2 | 12.05 ± 3.17 | 11.90 ± 4.0 | −0.97 ± 2.6 | 0.147 | 0.364 |

| Control | 14.04 ± 9.2 | 12.34 ± 2.8 | 12.20 ± 2.6 | −1.84 ± 8.7 | 0.116 | ||

| RANTES, ng/mL | DASH group | 42.70 ± 21.1 | 41.7 ± 20.7 | 38.09 ± 18.5 | −4.66 ± 26.3 | 0.060 | 0.030 |

| Control | 34.69 ± 22.7 | 32.72 ± 18.4 | 40.94 ± 20.0 | 6.25 ± 24.6 | 0.134 | ||

| CXCL4, ng/mL | DASH group | 12.38 ± 4.1 | 9.27 ± 3.19 | 8.36 ± 2.3 | −4.01 ± 3.1 | 0.0001 | 0.00001 |

| Control | 10.98 ± 3.6 | 10.42 ± 4,9 | 13.05 ± 4.8 | 2.52 ± 5.0 | 0.009 | ||

| RANTES/CXCL4 ratio | DASH group | 3,54 ± 1.7 | 4.75 ± 2.4 | 4.77 ± 2.4 | 1.23 ± 2.9 | 0.001 | 0.06 |

| Control | 3.52 ± 2.8 | 4.20 ± 4.1 | 3.67 ± 2.8 | 0.15 ± 3.3 | 0.006 |

| Change in DASH Index | Study Groups | Δ CXCL4 | Δ RANTES | ΔRANTES/CXCL4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔDASH index | DASH group | 0.133; p = 0.410 | −0.277; p = 0.08 | −0.276; p = 0.08 |

| Control | 0.167; p = 0.307 | −0.06; p = 0.707 | −0.213; p = 0.192 | |

| ΔGrains index | DASH group | 0.044; p = 0.783 | −0.363; p = 0.02 | −0.344; p = 0.02 |

| Control | 0.042; p = 0.796 | 0.128; p = 0.465 | 0.102; p = 534 | |

| ΔVegetable index | DASH group | −0.310; p = 0.04 | −0.196; p = 0.22 | −0.301; p = 0.04 |

| Control | −0.163; p = 0.320 | −0.140; p = 0.394 | −0.061; p = 711 | |

| ΔFruit index | DASH group | 0.235; p = 0.142 | −0.223; p = 0.164 | −0.334; p = 0.03 |

| Control | 0.146; p = 0.374 | 0.076; p = 0.654 | 0.011; p = 0.946 | |

| ΔDairy index | DASH group | 0.09; p = 0.578 | −0.051; p = 0.736 | −0.01; p = 0.937 |

| Control | −0.170; p = 0.293 | −0.183; p = 0.264 | −0.102; p = 0.533 | |

| ΔNuts index | DASH group | −0.221; p = 0.893 | −0.194; p = 0.230 | −0.101; p = 0.534 |

| Control | 0.116; p = 0.480 | 0.175; p = 0.286 | 0.007; p = 0.962 | |

| ΔFat index | DASH group | 0.243; p = 0.130 | −0.205; p = 0.202 | −0.269; p = 0.09 |

| Control | 0.001; p = 0.990 | 0.07; p = 0.653 | 0.003; p = 0.984 | |

| ΔMeat index | DASH group | 0.230; p = 0.153 | −0.128; p = 0.429 | −0.16; p = 0.323 |

| Control | 0.013; p = 0.932 | −0.183; p = 0.264 | −0.167; p = 0.307 | |

| ΔSweets index | DASH group | −0.001; p = 0.96 | −0.228; p = 0.156 | −0.210; p = 0.174 |

| Control | 0.128; p = 0.434 | −0.03; p = 0.816 | −0.136; p = 0.408 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makarewicz-Wujec, M.; Henzel, J.; Kruk, M.; Kępka, C.; Wardziak, Ł.; Trochimiuk, P.; Parzonko, A.; Demkow, M.; Dzielińska, Z.; Kozłowska-Wojciechowska, M. The Effect of Intensive Dietary Intervention on the Level of RANTES and CXCL4 Chemokines in Patients with Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomised Study. Biology 2021, 10, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10020156

Makarewicz-Wujec M, Henzel J, Kruk M, Kępka C, Wardziak Ł, Trochimiuk P, Parzonko A, Demkow M, Dzielińska Z, Kozłowska-Wojciechowska M. The Effect of Intensive Dietary Intervention on the Level of RANTES and CXCL4 Chemokines in Patients with Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomised Study. Biology. 2021; 10(2):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10020156

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakarewicz-Wujec, Magdalena, Jan Henzel, Mariusz Kruk, Cezary Kępka, Łukasz Wardziak, Piotr Trochimiuk, Andrzej Parzonko, Marcin Demkow, Zofia Dzielińska, and Malgorzata Kozłowska-Wojciechowska. 2021. "The Effect of Intensive Dietary Intervention on the Level of RANTES and CXCL4 Chemokines in Patients with Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomised Study" Biology 10, no. 2: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10020156

APA StyleMakarewicz-Wujec, M., Henzel, J., Kruk, M., Kępka, C., Wardziak, Ł., Trochimiuk, P., Parzonko, A., Demkow, M., Dzielińska, Z., & Kozłowska-Wojciechowska, M. (2021). The Effect of Intensive Dietary Intervention on the Level of RANTES and CXCL4 Chemokines in Patients with Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomised Study. Biology, 10(2), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10020156