Abstract

Nowadays, edible coatings incorporated with nanostructures as systems of controlled release of flavors, colorants and/or antioxidants and antimicrobial substances, also used for thermal and environmental protection of active compounds, represent a gap of opportunity to increase the shelf life of food highly perishable, as well as for the development of new products. These functionalized nanostructures have the benefit of incorporating natural substances obtained from the food industry that are rich in polyphenols, dietary fibers, and antimicrobial substances. In addition, the polymers employed on its preparation, such as polysaccharides, solid lipids and proteins that are low cost and developed through sustainable processes, are friendly to the environment. The objective of this review is to present the materials commonly used in the preparation of nanostructures, the main ingredients with which they can be functionalized and used in the preparation of edible coatings, as well as the advances that these structures have represented when used as controlled release systems, increasing the shelf life and promoting the development of new products that meet the characteristics of functionality for fresh foods ready to eat.

1. Introduction

Current global consumer trends demand minimally-processed products with characteristics such as “freshly-made” and “microbiologically-safe”. One key goal of minimally-processed products is maintaining and delivering fresh products in a convenient way without losing nutritional quality but ensuring sufficient shelf life to allow their distribution to potential consumers [1]. Technologies available for obtaining minimally-processed products include edible coatings, which are systems that provide safety and functionality while also increasing shelf life and food quality [2]. Today, edible coatings are strongly impacting food processing due to their advantages over synthetic films. Edible coatings can be used to physically protect food, prevent drain of liquid, and control the physical, chemical and microbiological activities of products [3]. In addition to being edible, they constitute a barrier to gases and water vapor, and can function as carriers of bioactive substances with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, as well as dyes, flavorings, prebiotics and probiotics, among other important compounds.

One classification of edible coatings is based on the material used to prepare them. The principle materials used in this technology are polysaccharides, proteins and lipids [4]. Hence, the functionality of edible coatings depends largely on the components of the film and on the interaction with the product to which they are applied. The choice of film-forming material and/or active substance depends on the desired objective, the nature of the food product, and the specific application [2].

Currently, interest is growing in the formulation, study and application of nanostructures in various fields of knowledge, including food science, due primarily to their excellent properties as vectors for delivering bioactive substances and systems for bioimaging and biodetection [5]. Nanotechnology is defined as the production, processing and application of nanometer-scale materials [6]. Nanostructured materials have applications in the food industry that include acting as nanosensors and incorporation into new packaging materials with better mechanical and barrier properties, but these materials also improve solubility and bioavailability, facilitate controlled release and protect bioactive substances during manufacturing and storage [7]. This indicates that adding functionalized nanostructured systems to edible coatings has a great impact, since they offer improved properties—including those just described—that may lead to new applications apart from those already reported in the literature.

Regulation of the use of nanostructures in foods is a controversial issue. In the United States, FDA issued three final guidance documents related to the use of nanotechnology in regulated products, including cosmetics and food substances. Currently, there is a lack of accepted regulations on the response to public health and general occupational risks associated with the manufacture, use and elimination of nanomaterials, with uncertainty regarding the risk characteristics [8,9].

Food nanotechnology can affect the bioavailability and nutritional value of food based on its functions. It is recognized that the biological properties (including toxicological effects) of nanomaterials are largely dependent on their physicochemical parameters [8].

Our research group has developed nanostructuring methodologies of various bioactive substances, which have been used on the conservation of food as edible coatings. It is for this reason that the main objective of this review, then, is to highlight the applications of functionalized nanostructured systems and their potential uses in edible coatings by presenting a general overview of the matrices that have been used and of the active substances that have potential for use in food processing. The article concludes with comments on future perspectives for food science.

2. Nanostructured Matrices

Some components of interest in food that serve as a matrix of certain nanostructures are found naturally on the submicron scale, which facilitates the process of nanostructuring them in individual or conjugated forms. These components are numerous and diverse, so we will deal only with proteins, carbohydrates and lipids, which can be combined to form complex colloidal mixtures with important physical and chemical properties, as described below.

2.1. Polysaccharides

Among the matrices that have been widely-used to form nanostructures in food science, we find polysaccharides. These biopolymers are made up of multiple saccharides linked by glycosidic bonds. There are different types of polysaccharides, which differ in terms of molecular weight, polydispersity, solubility, structure (linear or branched), and whether they are monofunctional or polyfunctional, among other factors. The various structures and properties of polysaccharides offer molecular and biological advantages when used to prepare nanostructures [10]. Depending on their specific properties, polysaccharides have important functionalities in the formation of nanostructures that impact food science, especially in the preparation of edible coatings. Nanostructures based on effective support matrices that make them functional for use with bioactive substances offer such properties as controlled release as a function of pH [11].

There is now abundant research on the synthesis of polysaccharide-based nanostructures [12], much of it focused on the functionality of polysaccharides and/or the controlled release of natural ingredients. One clear example is starch, which can be nanostructured and functionalized with bioactive substances for targeted administration. These bioactive substances may be hydrophilic or lipophilic in nature. Studies show that starch-based nanosystems have higher encapsulation efficiency and offer better protection of bioactive substances [13]. In addition, the use of cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) has significant advantages for the formulation of biofilms, since adding certain amounts of them can positively modify optical and gas barrier properties [14].

Studies by [15] with chitosan nanostructures have shown that these compounds can form effective delivery systems for bioactive substances—such as polyphenols—that can be incorporated into functional foods, since they have properties appropriate for this purpose, among which particle size (300–600 nm) stands out. Regarding the preparation of nanosystems, methodologies for the nanostructuring of enzymes such as lipase in guar gum matrices using dialysis have been developed [16] and present great potential for applications in functional foods, including edible coatings. Coatings made with nanochitosan applied to apples showed positive results on changes in fruit respiration by decreasing maximum ethylene production (33%), while also controlling the enzymatic activity of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase [17]. In addition, novel developments have been achieved in the field of edible coatings with a nanocomposite of silver/titanium dioxide/chitosan adipate (particle size = 50–100 nm) by photochemical reduction [10], which exhibits high zeta potential (from 30.1 to 33.0 mV) during 60 days of storage. In addition, this nanocomposite six-log reduced the population of Escherichia coli after 24 h of incubation, thus revealing its potential antibacterial protective power for fruit storage.

2.2. Lipids

Lipid-based nanostructures are innovative administration systems similar to emulsions, but that differ in size and structure. Their water-insoluble core is dispersed in a combination of solid and liquid lipids stabilized by surfactants. Important properties of nanostructured lipid matrices include high encapsulation efficiency, controlled release, and directed effect, among others [18,19]. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanolipid carriers play significant roles in lipid-based nanostructured systems. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) are submicron-size colloidal lipid systems that are fully crystallized and have an organized structure in which the bioactive components is housed inside the lipid matrix. They have been developed to encapsulate and administer functional lipophilic components [20,21]. Nanolipid carriers (NLC), meanwhile, are prepared by dispersing a mixture of solid and liquid lipids with bioactive ingredients in water together with emulsifiers. The mixture of lipid substances in NLC promotes a slow polymorphic transition and low crystallinity index [19]. The composition of the internal phase of NLC provides high encapsulation efficiency with greater bioavailability of the nanoencapsulated systems [22].

Several projects have been carried out on the development of nanostructured systems with a lipid base. Compritol 888 ATO, for example, has been used to form SLN with approximate sizes of 241–333 nm with ultrasound as a complementary technique to ultrahigh agitation [23]. Glycerol monostearate has been incorporated as a lipid nanomatrix using high pressure homogenization techniques that have shown great effectiveness in the efficiency of citral encapsulation (above 50%) [24]. Palmitic acid and corn oil have also been employed to form SLN. In this case, crystals of palmitic acid enveloped the oily surface of the encapsulated β-carotene, while corn oil decreased the exclusion of β-carotene from the matrix to the surface [25]. SLN prepared with Candeuba® wax (Multiceras S.A. de C.V., Monterrey, Mexico), meanwhile, present values of zeta potential (ζ) = −25.7 mV, after three cycles of ultrahigh homogenization, and have shown excellent results on increasing the shelf life of guava [21]. Since ζ is a measure of the degree of repulsion between similarly-charged particles in the dispersion, colloids with a high z (either positive or negative) are electrically-stabilized [6].

Turning to NLC, formulations elaborated with different concentrations of solid lipids (lauric acid, stearic acid, and cacao butter), oils (glycerol, Miglyol® 812, corn oil, and oleic acid), and surfactants (Poloxamer 407, Tween 80, and Tween 20) were used, highlighting their great potential for use in food applications thanks to their ability to maintain the chemical stability (NLC was successfully protected the chemical structure of t-resveratrol from decomposition phenomena). In addition, they all have average particle sizes below 120 nm [18]. Cocoa butter as an NLC has shown significant advantages in the encapsulation of active substances, such as the essential oil of cardamom, where it has generated encapsulation efficiencies above 90%, accompanied by particle sizes below 150 nm [26].

2.3. Proteins

In recent years, research has shown that proteins derived from corn, wheat, soy, peanuts, milk or gelatin are excellent options for the formation of edible coatings, because they present hydrophilic surfaces that provide resistance to the diffusion of water vapor and constitute a barrier to the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide [4]. Moreover, these proteins are naturally of submicron size and some of them can self-assemble into complexes or larger nanostructures with the potential to play vital biological roles. Such nanostructuring of proteins holds promise for uses in foods given their gelling, thickening and emulsifying properties [27], which makes them candidates for incorporating specific matrices in food preservation, such as edible coatings, because they modify the mechanical and rheological properties of food [28].

The nanostructuring of proteins has stimulated great interest in the scientific community due to the properties it offers, including biodegradability and availability [29]. In addition, protein nanostructures present greater stability in biological fluids and so allow the controlled release of bioactive substances of interest in foods [30]. One clear example is that numerous studies of the nanostructuring of zein are currently being conducted and showing great potential for applications in foods. Nanostructured zein systems are advanced submicron support systems that show improved properties in terms of stability, release of bioactive substances and supply efficiency [31].

Studies have also been conducted on the nanostructuring of such proteins as gelatin and bovine serum albumin, and they show promise for the effective delivery of resveratrol and curcumin by obtaining average particle sizes of 315 nm [29]. Various nanohydrogels have been formed using proteins of distinct origin, such as milk and soy protein. When used as coatings, results show that they are efficient vehicles for entrapping, protecting and delivering nutraceuticals and bioactive components [32].

Another area of research on the nanostructuring of proteins as edible coatings involves the formation of nanofibers based on whey protein. In this case, in vitro nanosystem increased the transparency of the films while decreasing moisture content and solubility in water. In addition, when applied to freshly-cut apple they exhibited the best protective action in terms of retaining total phenolic content and inhibiting darkening and weight loss [33].

3. Active Substances in the Functionalization of Nanostructures

Edible coatings can be effective carriers of functional ingredients, which can perform various functionalities, such as increasing the shelf life of products and delaying undesirable changes in fresh products [4]. This section discusses different active substances that have the ability to be nanostructured and, moreover, present potential for applications in edible coatings.

3.1. Antioxidants

Antioxidants are substances that, when present in foods at low concentrations compared to that of an oxidative substrate, markedly delay or prevent oxidation [34,35,36]. According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), antioxidants are defined as substances used to preserve food by retarding deterioration, discoloration and rancidity due to oxidation [36]. Food manufacturers have used food-grade antioxidants to prevent quality deterioration of products and maintain their nutritional value [34]. Antioxidant compounds are classified into natural and synthetic types. Of the latter category, butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and propyl gallate (PG) are the ones most widely-used in food preservation. However, due to the potential carcinogenic properties of synthetic antioxidants, many researchers are striving to replace them with natural substances [37]. In addition, growing consumer preference for natural food additives is shifting emphasis to natural materials as sources of novel antioxidants. Phenolic compounds (phenolic acids and flavonoids), carotenoids (β-carotene and lycopene), tocopherols (vitamin E) and ascorbic acid (vitamin C) are the most extensively-studied and oft-used natural antioxidants in the food industry.

The reaction mechanism of antioxidant compounds depends mainly on their structure. In this regard, five antioxidant routes have been identified: (i) scavenging species that initiate peroxidation; (ii) chelating metal ions so that they are unable to generate reactive species or decompose lipid peroxides; (iii) quenching to prevent the formation of peroxides; (iv) breaking the autoxidative chain reaction; and (v) reducing localized concentrations [35]. Phenolic acids (gallic acid) are characterized by a C6–C1 structure [38] and generally act as antioxidants by trapping free radicals [39]. Flavonoids (quercetin, hesperetin, catechins, epicatechins, and proanthocyanidins) constitute the largest group of plant phenolics [40]. They are low-molecular weight compounds made up of 15 carbon atoms arranged in a C6–C3–C6 configuration [38]. Their free radical-scavenging potential appears to depend on the pattern (both number and location) of free –OH groups on the flavonoid skeleton [41], since they have the ability to donate a hydroxyl hydrogen group and stabilize the resonance of the resulting antioxidant radical [42]. Carotenoids, meanwhile, are lipid soluble C40 tetraterpenoids. These compounds are divided into xanthophylls, which contain oxygen (astaxanthin), and carotenes, which are pure hydrocarbons with no oxygen in their structure (α-carotene, β-carotene and lycopene) [38]. Carotenoids have the capacity to scavenge peroxyl radicals (ROO) more efficiently than any other reactive oxygen species (O2, , OH, RO, H2O2 and LOOH), which allows them to deactivate ROO by reacting with them to form resonance-stabilized, carbon-centered radical adducts [42].

Finally, vitamins are the best-known antioxidant compounds, with C and E being the ones most frequently used in the food industry. Vitamin C is a water-soluble free radical scavenger that changes into an ascorbate radical by donating an electron to the lipid radical to terminate the lipid peroxidation chain reaction. Vitamin E, meanwhile, performs a chain-breaking function during lipid peroxidation and exerts its antioxidant effect by scavenging lipid peroxyl radicals [42]. Other natural antioxidants, such as curcumin, also show chain-breaking antioxidant activity, as their free radical scavenging correlates to the phenolic –OH group and the CH2 group of the β-diketone moiety. It is important to note, however, that the application of antioxidants is limited by factors that include the low solubility of hydrophobic types, poor stability, degree of bioavailability, and targeted specificity [43,44,45]. Functionalizing nanostructures is currently being explored as a possible means of resolving these problems (Table 1), since submicronic size particles have been shown to enhance both bioavailability and stability, and to provide controlled release of the compounds involved [46], while also providing excellent results with respect to parameters such as particle size and encapsulation efficiency.

Table 1.

Various antioxidants used in the functionalization of nanostructures.

3.2. Antimicrobials

Antimicrobial agents have long been studied for their effectiveness in killing or inhibiting the growth of microorganisms in and on foods [60,61]. These efforts have been directed towards increasing food safety for consumers and the shelf life of food products by reducing or eliminating pathogens and microorganisms that cause spoilage. Antimicrobials widely-used in food preservation include those of non-natural and natural origin. In the first category, fungicides and triclosan are highlighted, while those called “natural” can be classified into animal source antimicrobials as proteins, enzymes and polysaccharides (lactoferrine, lysozyme and chitosan); microbial products such as bacteriocins (nisin and pediocin); plant delivered compounds as spices, essential oils and plant extracts; and metals (ZnO, Au and Ag) [62]. Nevertheless, another natural antimicrobial is not included within this classification. Electrolyzed water (EW) is one of the alternative storage technologies for fresh meat products and has attracted increasing attention because of its good antimicrobial effect [63]. All of them have been shown to present specific action mechanisms. Phenolic compounds (essential oils and plant extracts), metals, enzymes, bacteriocins and EW are known to damage the cell wall of microorganisms, while inorganic compounds such as triclosan inhibit the synthesis of fatty acids. As is the case of most bioactive compounds, antimicrobials are chemically-reactive species that are susceptible to degradation through interaction with food ingredients and/or when exposed to environmental conditions [60].

Table 2 identifies some studies on the functionalization of nanostructures with antimicrobial compounds such as NPs, nanovesicles, nanofibers and carbon nanotubes that seek to improve the physical stability of the structures, monitored mainly through the particle size, as well as its chemical stability, determined through the degradation of the antimicrobials and its bioavailability. In a similar vein, studies of the potential effect of these systems on the inactivation of pathogenic microorganisms (Salmonella spp., L. monocytogenes, C. jejuni, E. coli, and S. aureus) and prevention of food spoilage have also been conducted. On this point [64], and [65] focused their work—with some success—on developing nanostructures that are capable of interacting with polymeric matrices, such as polylactic acid or thermoplastic flour, in packaging production. However, according to the literature reviewed, many nanostructures have both the potential to be functionalized with antimicrobial agents and the properties required to interact with natural or synthetic materials that could be incorporated into new antimicrobial packaging systems.

Table 2.

Recent studies of the functionalization of nanostructures with antimicrobials.

3.3. Probiotic and Pre-Biotic

The science of food conservation is constantly on the lookout for new ingredients that, aside from helping preserve quality, are important for the ingestion of so-called functional foods; that is, foods which, in addition to nutrients, contain components that produce a positive impact on health. These include prebiotics and probiotics. A probiotic is a live microbial food supplement that has beneficial exerts for the host by improving its microbiological balance in the intestine [77]. The most commonly-used probiotics are lactic acid excretors such as lactobacilli and bifidobacterial [78]. Probiotics have been incorporated into several food products and supplements, mostly dairy products such as cheeses, dairy desserts and ice cream, though fermented milks such as yogurts are the most popular matrices [79]. The global market for probiotics has been expanding in recent years due to growing consumer demand for healthy diets and wellness [79].

A prebiotic, in contrast, is a non-digestible substance that provides a beneficial physiological effect on the host by selectively stimulating growth or activity of a limited number of indigenous bacteria [80]. Prebiotics are non-active food constituents that migrate to the colon where they are selectively fermented [81]. This category includes both natural and chemically-produced substances [82]. Lactulose, galactooligosaccharides, fructooligosaccharides, inulin and its hydrolysates, maltooligosaccharides, and resistant starch are all prebiotics commonly used in human diets [81]. Naturally-occurring prebiotics can be found in various foods, including asparagus, chicory, tomatoes and wheat, and they are natural constituents of breast milk. Prebiotics and probiotics have been associated with several health benefits, such as increasing the bioavailability of minerals—especially calcium—modulating the immune system, preventing the incidence or reducing the severity and duration of gastrointestinal infections such as acute diarrhea, and modifying inflammatory conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis and inflammatory bowel disease, among others [83].

Currently, mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics are often used to take advantage of their synergic effects in applications with food products. Mixtures of this kind are called synbiotics [81]. They improve the survival, implantation and growth of newly-added probiotic strains, or promote growth of existing strains of beneficial bacteria in the colon [84]. These compounds are very important for the body, since, to exert their positive health effects, these bacteria must reach their site of action alive and establish themselves in certain quantities [85]. However, the acidic conditions of the stomach, together with the bile salts secreted into the duodenum, are formidable obstacles to the survival of ingested bacteria [86]. For this reason, it is necessary to protect them with a physical barrier that prevents exposure to adverse environmental conditions. Several options have been explored to provide the protection that these compounds require. One recent discovery is that microencapsulation is a useful technique for stabilizing probiotics in functional food applications [87]. Reviews of some other works reveal deeper probes into the science of the encapsulation of probiotics and research on different methods [88,89,90,91,92]. Alternatively, probiotics may be carried inside edible polymer matrices similar to the ones used in the food packaging industry. Probiotics and many other active compounds [93] have been incorporated into biopolymeric matrices to develop active/bioactive food packaging materials as an alternative method for controlling pathogenic microorganisms and improving food safety, coupled with the potential to favor consumer health. Incorporating probiotic cultures into edible coatings was first proposed in 2007 by [94], but several later studies have successfully microencapsulated bacteria using various materials and methods. In addition to showing their use in edible coatings with different matrices, Table 3 also presents the most recent studies that have encapsulated probiotics and prebiotics in distinct matrices that help protect them from adverse environmental conditions and so keep them alive.

Table 3.

Recent studies that containing probiotic and pre-biotic in different matrix.

3.4. Colorants and Flavors

Colorants and flavors can be synthetics or naturals. Natural flavors and colorants are preferred in food preparation and development of new products. Products that present wavelengths within 380–770 nm allow the perception of different colors through the human eye [112,113,114]. Naturals colors and flavors have advantages on the health and safety such as antioxidant and antimicrobial effects, which give the characteristic of functional food when they are applied in food process. Flavors have numerous volatile substances that are susceptible to loss, thus the formation of nanostructures to protect these flavors is an alternative in the food process. Nanostructures have been formed by ionic gelation using chitosan, or by emulsification-diffusion using poly-ε-caprolactone [115]. Table 4 shows same colorants nanostructured.

Table 4.

Recent studies of nanostructured matrix containing colorants.

Table 5 presents nanostructured flavors, showing that nanoencapsulation is the principal form of protection. The retention of flavor in submicronic systems depends largely on the physicochemical properties of aromatic compounds and components of the food matrix [124].

Table 5.

Recent studies of nanostructured matrix containing flavors for food applications.

4. Effect of the Functionalization of Nanostructures in Edible Coatings

The preceding paragraphs reviewed important aspects of the materials, active compounds and substances involved in the preparation of nanostructures. Today, commercial interest in foods with functional characteristics that increase shelf life during storage is growing rapidly. However, many cases require a specific functionality at the time of consumption, such as digestive enhancers and anticarcinogenic and anti-cholesterol properties, among others. In addition, these materials must be effective in combatting microorganisms to improve consumer safety [130]. Several different natural polymers have been used in the preparation of edible coatings. Some preparation methods include crosslinking polymer molecules with a crosslinker substance, while others require temperature control and the addition of inorganic substances such as mechanical resistance reinforcers and gas permeability modifiers [79,131,132]. This explains why edible coatings options are increasing the potentialities of functionality and providing effective protection when added to submicron-sized systems that can incorporate bioactive substances with antimicrobial and/or antioxidant properties, such as essential oils (oregano, rosemary, cinnamon, lavender, citrus, mint, peppermint and curcumin, among many others). All these substances have been functionalized by small nanostructures that are incorporated into edible coatings using different preparation methods. It is important to note that it is preferable to use natural polymers such as alginates, carboxymethylcellulose, pectin, zein, whey, casein, etc. [133]. Incorporating these nanostructures helps improve the barrier and mechanical properties of edible coatings, especially nano- clays, zinc oxides, titanium and zeolites, to mention just a few. It is possible to incorporate active substances by adsorption methods that modify their functionality to preserve foods and the nutrimental components of edible coatings [134,135].

The functionalization of nanostructures allows them to reduce the volatility and sensitivity of antioxidant compounds to temperature, light and oxygen exposition, and increase solubility and affinity for the components of edible coatings, thus increasing their compatibility with the surface of the food and favoring preservation. These systems are able to persist during storage, distribution and commercialization of food as they are gradually released from the nanostructure towards the components of the edible coating [120,136]. Another important objective in pursuing the functionalization of nanostructures is to protect the flavors of foods that have such characteristics as sweetness and floral, spicy and menthol smells, among others. Here, challenges include the volatility of these properties, their short endurance, and their vulnerability to changes in sensory perception due to oxidation and exposure to temperature and chemical interactions. For these reasons, developing systems of submicron size can improve the entrapment and decrease the degradation of many essential oils, phenols and plant extracts with antimicrobial and antioxidant activity [137].

The possibilities for developing edible coatings are now innumerable, due to the existence of different composition matrices for coatings, different structures and compositions of nanostructures, and the functionalization of these materials with different antioxidants, antimicrobials, permeability modifiers and mechanical properties, to mention just a few. The benefits for food preservation will be further enhanced with the development of controlled release systems and others with special characteristics designed to control respiration, enzymatic activity in the maturation of cheeses, and microbial control in meat, bread and other food products. Table 6 shows some of the main applications of edible coatings based on different matrices that incorporate functionalized nanostructures with different components, all with a focus on the benefits potentially obtained for commercializing products with minimal processing or with functional and special sensorial characteristics that are attractive to consumers.

Table 6.

Some nanostructures employees in edible coatings for food preservation.

Table 6 shows that most coatings are used for fruit preservation, because these food items are usually consumed directly without treatment and, therefore, are among the foods most often purchased by consumers, while other foods—e.g., meat, fish, cheese, chocolate, etc.—can be packaged in film coatings with different nanostructures, classified as active food packaging because the coatings are prepared in ways similar to edible coatings that are applied directly to the food.

5. Release of the Active Substances in Edible Coatings

Different strategies and methods of functionalization of nanostructures are carried out to increase the encapsulation efficiency (usually 10%–75%). They depend on the type of encapsulating polymer—alginate, chitosan, zein, pectin, starch, poly-ε-caprolactone, poly-lactic acid, etc.—and the properties of the bioactive substance used [146]. The selection of the wall material, the substance to be encapsulated, and the support matrix for developing an edible coating are directly related to the kinetics of the release of the active ingredient contained in the functionalized nanostructures and embedded in a matrix usually formed by edible polymers. Other important considerations are the different barriers that the bioactive substance must cross to interact with the food surface and fulfill the primary function of increasing the commercialization time while maintaining freshness, characteristics and/or functional properties. Therefore, the establishment and study of the kinetics of release of functionalized bioactive materials in nanostructures is of great importance since it makes it possible to analyze kinetics and relate this to increased shelf-life [147].

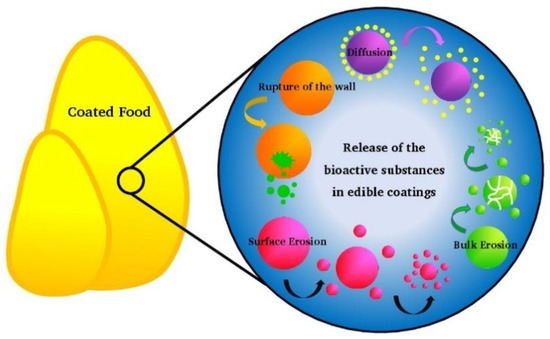

One of most attractive effects of the use of edible coatings is the ability to control the release of bioactive compounds, considering parameters such as humidity, temperature, pH, and swelling of the matrix, among other conditions that may affect the diffusivity of substances with antimicrobial or nutraceutical effect, at different times during food storage or ingestion [148]. Several different mechanisms may be involved in the release of an active compound through the components of edible coatings. These include melting, degradation, swelling or rupture of nanostructures, or diffusion release as a function of the initial solubility of the bioactive compound in the nanostructure and the permeability of the bioactive compound across the core of the polymer and, later, in the matrix of the edible coating. Different release models can be used to explain this, so the release kinetics can be of distinct types since they depend on both time and the way in which the matrix is modified. Thus, the non-time-dependent zero-order release kinetic Mt = k0t + M0, which has a constant release of the active compound (k0), helps maintain its concentration and thus preserve food quality. However, they have the disadvantage that they can be removed quickly from the coating surface, causing them to lose their food-conservation properties. First-order kinetic release is expressed by the equation: log Mt = log M0 − k1t/2.303, where M0 is the initial active concentration, k1 is the first-order rate constant, and t is time. This type of kinetic release is time-dependent and takes into account variations in the concentration of the bioactive compound as a function of storage time and its release into the edible coating to increase release during storage [120,149].

Figure 1 presents the different forms of release of a bioactive substance when functionalized in a nanostructure, and its potential incorporation into the polymer matrix employed in the edible coating formulation. This indicates that the ways of modifying the polymeric wall of functionalized nanostructures and the matrix polymeric employed in the formulation of the edible coating can provide other release kinetics that may explain the behavior of the bioactive substance used in food preservation, such as the release kinetics of a bioactive ingredient transferred through different functionalized nanostructures to the edible coatings [58,150]. The following is a brief description of some of the most commonly-used models to describe release kinetics, including the Korsmeyer–Peppas approach, which considers the cumulative release of the component with respect to time, is represented by the equation: Mt/M1 = k’tη, where Mt/M1 is a fraction of the active substance released at time t, k’ is the release rate constant, and η is the release exponent [149,151]. The value of “η” predicts the release mechanism of the active substance such that η = 0.45 corresponds to the Fickian diffusion mechanism; 0.45 < η < 0.89 to non-Fickian transport; η = 0.89 to Case II transport; and h > 0.89 to super case II transport [152]. Other models of polymer matrices consider the dissolution of the bioactive compound, as in the case of Higuchi, who presented an empirical model for water soluble and poorly water-soluble active compounds, described as follows: Qt = kHt1/2, where Qt is the amount of the active substance released at time t, and kH is the release rate constant for Higuchi’s model [153,154]. Finally, a model used to describe the release of the bioactive substance across an edible coating is the Weibull model, which has been described for different dissolution processes. It considers the relation Mt = M0[1 − e(t − T)b/a], where a denotes a scale parameter that describes the time dependence, and b describes the shape of the curve which corresponds exactly to the shape of an exponential profile [149].

Figure 1.

Release process in edible coatings incorporated with functionalized nanostructures.

The release of a bioactive substance with low molecular weight from a homogeneous, swelling polymeric network can produce the diffusion of water into the polymeric matrix, followed by matrix relaxation with the subsequent diffusion of the active compound out of the swollen polymeric network onto the food surface in edible coatings [155]. Table 7 shows some studies that have explored controlled release in nanostructures functionalized with different bioactive compounds and incorporated into an edible coating. Many of these works have developed the release of the active substance only from the edible coating “in vitro”, and only a few have analyzed applications in foods [156]. Finally, to highlight the release behavior of bioactive compounds in edible coatings, some studies have incorporated microcapsules or essentials oil directly into the coating matrix.

Table 7.

Recent studies on delivery and kinetics of nanostructures in edible coatings.

6. Conclusions and Future Trends

Currently, nanoengineered structures containing bioactive substances have a fundamental role in food processes, particularly for food preservation. Thus, the use of submicron systems represents great advantages in contrast to the systems of conventional size, since these improve the initial properties of the materials increasing the interaction of the active components with food surface. These systems can adapt to different conditions such as ionic strength, thermal resistance, pH, food composition, etc., keeping their capacity to release bioactives and, in several cases, spatial ubication. The diversity of nanostructures reviewed, solid lipid nanoparticles, polymeric nanospheres and nanocapsules, nanogels, liposomes, lipid carrier nanoparticles, etc., shows the possibility to adapt their architecture and composition to the functionalization with diverse substances such as pre-biotics, pro-biotics, antimicrobial, antioxidants, colorants, flavor, etc. Their application is diverse and still need further study, in particular their interactions with food cellular structures or tissues. Edible coatings are the best way to apply these functionalized nanostructures on the food in a homogenous and safe way with minimal processing steps and using conventional equipment. The edible coatings prepared with functionalized nanostructures can be considered a versatile tool for long-term food preservation complying with safety aspects. Future trends include the development of composite edible coatings, containing two or more nanostructured systems, which have improved gas barrier properties, greater firmness to the products, enhance or add colors and flavors unique to defined products and increase the meaningful nutritional value.

Author Contributions

This paper was written by all authors. Ricardo M. González-Reza wrote the Abstract, the Introduction and about nanostructured matrices; compiled information; and realized figure and graphical abstract. Claudia I. García-Betanzos wrote about antimicrobial and antioxidants as active substances in edible coatings. Liliana I. Sánchez-Valdes wrote about pre-biotics and pro-biotics with potential use in edible coatings. María A. Cornejo-Villegas wrote about colorants and flavors. David Quintanar-Guerrero reviewed documents and wrote the Conclusions and Future Trends. María L. Zambrano-Zaragoza wrote about effect of functionalization of nanostructures in edible coatings and release of active substances in edible coatings, and approved the final document.

Acknowledgments

The authors also acknowledge the financial support provided by PAPIIT: IT201617 from DGAPA-UNAM and CONACyT CB-221629.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviation

| CG | Cashew gum |

| CMC | Carboxymethyl cellulose |

| CNC | Cellulose nanocrystals |

| CS | Chitosan |

| L-NVs | Lipid-based nanovesicles |

| NCs | Nanocapsules |

| NGs | Nanogels |

| NLC | Nanolipid carrier |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| NSs | Niosomes |

| PCL | Poly-ε-caprolactone |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| PLGA | Polylactide-co-glycolide |

| SLN | Solid Lipid Nanoparticles |

| TG | Tragacanth gum |

References

- Rahman, M.S. Hurdle Technology in Food Preservation. In Minimally Processed Foods: Technologies for Safety, Quality, and Convenience; Siddiqui, M.W., Rahman, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Embuscado, M.E. Edible Films and Coatings for Food Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-387-92823-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani, S.; Hosseini, S.V.; Regenstein, J.M. Edible films and coatings in seafood preservation: A review. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousuf, B.; Qadri, O.S.; Srivastava, A.K. Recent developments in shelf-life extension of fresh-cut fruits and vegetables by application of different edible coatings: A review. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 89, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.; Hernandez-Martinez, A.R.; Pool, H.; Molina, G.; Cruz-Soto, M.; Luna-Barcenas, G.; Estevez, M. Synthesis and functionalization of silica-based nanoparticles with fluorescent biocompounds extracted from Eysenhardtia polystachya for biological applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 57, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.L.; Mercado-Silva, E.; Gutiérrez-Cortez, E.; Castaño-Tostado, E.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D. Optimization of nanocapsules preparation by the emulsion-diffusion method for food applications. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathakoti, K.; Manubolu, M.; Hwang, H.-M. Nanostructures: Current uses and future applications in food science. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Hwang, H.M. Nanotechnology in food science: Functionality, applicability, and safety assessment. J. Food Drug Anal. 2016, 24, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.L.; González-Reza, R.; Mendoza-Muñoz, N.; Miranda-Linares, V.; Bernal-Couoh, T.F.; Mendoza-Elvira, S.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D. Nanosystems in edible coatings: A novel strategy for food preservation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Monty, J.; Linhardt, R.J. Polysaccharide-based nanocomposites and their applications. Carbohydr. Res. 2015, 405, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Han, S.; Zheng, H.; Dong, H.; Liu, J. Preparation and application of micro/nanoparticles based on natural polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 123, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, R.; Zia, K.M.; Tabasum, S.; Jabeen, F.; Noreen, A.; Zuber, M. Polysaccharide based bionanocomposites, properties and applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 92, 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F. Encapsulation and delivery of food ingredients using starch based systems. Food Chem. 2017, 229, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukyai, P.; Anongjanya, P.; Bunyahwuthakul, N.; Kongsin, K.; Harnkarnsujarit, N.; Sukatta, U.; Sothornvit, R.; Chollakup, R. Effect of cellulose nanocrystals from sugarcane bagasse on whey protein isolate-based films. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madureira, A.R.; Pereira, A.; Castro, P.M.; Pintado, M. Production of antimicrobial chitosan nanoparticles against food pathogens. J. Food Eng. 2015, 167, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumya, R.S.; Ghosh, S.; Abraham, E.T. Preparation and characterization of guar gum nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2010, 46, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardesh, A.S.K.; Badii, F.; Hashemi, M.; Ardakani, A.Y.; Maftoonazad, N.; Gorji, A.M. Effect of nanochitosan based coating on climacteric behavior and postharvest shelf-life extension of apple cv. Golab Kohanz. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 70, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babazadeh, A.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Hamishehkar, H. Formulation of food grade nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) for potential applications in medicinal-functional foods. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2017, 39, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katouzian, I.; Faridi Esfanjani, A.; Jafari, S.M.; Akhavan, S. Formulation and application of a new generation of lipid nano-carriers for the food bioactive ingredients. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.; Decker, E.A.; McClements, D.J.; Kristbergsson, K.; Helgason, T.; Awad, T. Solid lipid nanoparticles as delivery systems for bioactive food components. Food Biophys. 2008, 3, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.; Mercado-Silva, E.; Ramirez-Zamorano, P.; Cornejo-Villegas, M.A.; Gutiérrez-Cortez, E.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D. Use of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) in edible coatings to increase guava (Psidium guajava L.) shelf-life. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.H.; Radtke, M.; Wissing, S.A. Nanostructured lipid matrices for improved microencapsulation of drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 242, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righeschi, C.; Bergonzi, M.C.; Isacchi, B.; Bazzicalupi, C.; Gratteri, P.; Bilia, A.R. Enhanced curcumin permeability by SLN formulation: The PAMPA approach. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 66, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Lu, Z.; Li, D.; Hu, J. Preparation and characterization of citral-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles. Food Chem. 2018, 248, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrad, B.; Ravanfar, R.; Licker, J.; Regenstein, J.M.; Abbaspourrad, A. Enhancing the physicochemical stability of β-carotene solid lipid nanoparticle (SLNP) using whey protein isolate. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keivani Nahr, F.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Hamishehkar, H.; Samadi Kafil, H. Food grade nanostructured lipid carrier for cardamom essential oil: Preparation, characterization and antimicrobial activity. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 40, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynes, J.K.; Carver, J.A.; Gras, S.L.; Gerrard, J.A. Protein nanostructures in food—Should we be worried? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 37, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foegeding, E.A. Food biophysics of protein gels: A challenge of nano and macroscopic proportions. Food Biophys. 2006, 1, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, A.K.A.; El-Ahmady, S.H.; Hathout, R.M. Selecting optimum protein nano-carriers for natural polyphenols using chemoinformatics tools. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 1764–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, N.; Sahoo, R.K.; Biswas, N.; Guha, A.; Kuotsu, K. Recent advancement of gelatin nanoparticles in drug and vaccine delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 81, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.R.; Velikov, K.P. Zein as a source of functional colloidal nano- and microstructures. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 19, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaee, A.; Mohammadian, M.; Jafari, S.M. Whey and soy protein-based hydrogels and nano-hydrogels as bioactive delivery systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 70, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Wu, G.; Liu, C.; Li, D.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, X. Edible coating based on whey protein isolate nanofibrils for antioxidation and inhibition of product browning. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F. Antioxidants in food and food antioxidants. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2000, 44, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.S. Natural Antioxidants: Sources, Compounds, Mechanisms of Action, and Potential Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2011, 10, 221–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Free Radicals and Antioxidants: Human and Food System. Adv. Appl. Sci. Res. 2011, 2, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.-J.; Lee, J.-G.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, S.; Choi, M.-J.; Cho, Y. Changes in quality characteristics of pork patties containing antioxidative fish skin peptide or fish skin peptideloaded nanoliposomes during refrigerated storage. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2017, 37, 752–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grumezescu, A.M.; Holban, A.M. Impact of Nanoscience in the Food Industry, 1st ed.; Grumezescu, A.M., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gheldof, N.; Engeseth, N.J. Antioxidant capacity of honeys from various floral sources based on the determination of oxygen radical absorbance capacity and inhibition of in vitro lipoprotein oxidation in human serum samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3050–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, S.; Mussatto, S.I.; Martínez-Avila, G.; Montañez-Saenz, J.; Aguilar, C.N.; Teixeira, J.A. Bioactive phenolic compounds: Production and extraction by solid-state fermentation. A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupea, A.X.; Pop, M.; Cacig, S. Structure-radical scavenging activity relationships of flavonoids from Ziziphus and Hydrangea extracts. Rev. Chim. 2008, 59, 309–313. [Google Scholar]

- Nimse, S.B.; Pal, D. Free radicals, natural antioxidants, and their reaction mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27986–28006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Astete, C.E.; Sabliov, C.M. Entrapment and delivery of α-tocopherol by a self-assembled, alginate-conjugated prodrug nanostructure. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 72, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoond Zardini, A.; Mohebbi, M.; Farhoosh, R.; Bolurian, S. Production and characterization of nanostructured lipid carriers and solid lipid nanoparticles containing lycopene for food fortification. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Wang, D.; Sun, C.; McClements, D.J.; Gao, Y. Utilization of interfacial engineering to improve physicochemical stability of β-carotene emulsions: Multilayer coatings formed using protein and protein–polyphenol conjugates. Food Chem. 2016, 205, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, Q.; Scotter, M.; Blackburn, J.; Ross, B.; Boxall, A.; Castle, L.; Aitken, R.; Watkins, R. Applications and implications of nanotechnologies for the food sector. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2008, 25, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Huang, X.; Gong, Y.; Xiao, H.; Julian, D.; Hu, K. Enhancement of curcumin water dispersibility and antioxidant activity using core—Shell protein—Polysaccharide nanoparticles. Food Res. Int. 2016, 87, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sechi, M.; Syed, D.N.; Pala, N.; Mariani, A.; Marceddu, S.; Brunetti, A.; Mukhtar, H.; Sanna, V. Nanoencapsulation of dietary flavonoid fisetin: Formulation and in vitro antioxidant and alpha-glucosidase inhibition activities. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016, 68, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, Y.; Swift, S.; Ray, S.; Gizdavic-Nikolaidis, M.; Jin, J.; Perera, C.O. Evaluation of gallic acid loaded zein sub-micron electrospun fibre mats as novel active packaging materials. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3192–3200. [Google Scholar]

- El-Gogary, R.I.; Rubio, N.; Wang, J.T.W.; Al-Jamal, W.T.; Bourgognon, M.; Kafa, H.; Naeem, M.; Klippstein, R.; Abbate, V.; Leroux, F.; et al. Polyethylene glycol conjugated polymeric nanocapsules for targeted delivery of quercetin to folate-expressing cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 1384–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aceituno-Medina, M.; Mendoza, S.; Rodríguez, B.A.; Lagaron, J.M.; López-Rubio, A. Improved antioxidant capacity of quercetin and ferulic acid during in-vitro digestion through encapsulation within food-grade electrospun fibers. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 12, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Kumar, D.; Kumari, A.; Yadav, S.K. Encapsulation of catechin and epicatechin on BSA NPS improved their stability and antioxidant potential. EXCLI J. 2014, 13, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sanna, V.; Lubinu, G.; Madau, P.; Pala, N.; Nurra, S.; Mariani, A.; Sechi, M. Polymeric nanoparticles encapsulating white tea extract for nutraceutical application. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 2026–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyzioglu, G.C.; Tornuk, F. Development of chitosan nanoparticles loaded with summer savory (Satureja hortensis L.) essential oil for antimicrobial and antioxidant delivery applications. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 70, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, F.O.M.S.; Oliveira, E.F.; Paula, H.C.B.; Paula, R.C.M. De Chitosan/cashew gum nanogels for essential oil encapsulation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 89, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossio, O.; Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, M.; Vázquez-Lasa, B.; Román, J.S. Amphiphilic polysaccharide nanocarriers with antioxidant properties. J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 2014, 29, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Yao, P. Soy Protein/soy polysaccharide complex nanogels: folic acid loading, protection, and controlled delivery. Langmuir 2013, 29, 8636–8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamjidi, F.; Shahedi, M.; Varshosaz, J.; Nasirpour, A. Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC): A potential delivery system for bioactive food molecules. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2013, 19, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Decker, E.A.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Impact of lipid nanoparticle physical state on particle aggregation and {Œ}\le-carotene degradation: Potential limitations of solid lipid nanoparticles. Food Res. Int. 2013, 52, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donsì, F.; Annunziata, M.; Sessa, M.; Ferrari, G. LWT—food science and technology nanoencapsulation of essential oils to enhance their antimicrobial activity in foods. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 1908–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pornpattananangkul, D.; Hu, C.J.; Huang, C. Development of Nanoparticles for Antimicrobial Drug Delivery. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appendini, P.; Hotchkiss, J.H. Review of antimicrobial food packaging. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2002, 3, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Liu, Y.; Xie, J.; Wang, X. Effects of combined treatment of electrolysed water and chitosan on the quality attributes and myofibril degradation in farmed obscure puffer fish (Takifugu obscurus) during refrigerated storage. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaci, F.; Umu, O.C.O.; Tekinay, T.; Uyar, T. Antibacterial electrospun poly(lactic acid) (PLA) nano fi brous webs incorporating triclosan/cyclodextrin inclusion complexes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 3901–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woranuch, S.; Yoksan, R. Eugenol-loaded chitosan nanoparticles: II. Application in bio-based plastics for active packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 96, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashem, M.; Sharaf, S.; El-Hady, M.M.A.; Hebeish, A. Synthesis and characterization of novel carboxymethylcellulose hydrogels and carboxymethylcellulolse-hydrogel-ZnO-nanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 95, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajpai, S.K.; Chand, N.; Chaurasia, V. Investigation of water vapor permebility and antimicrobial property of zinc oxide nanoparticles-loaded chitosan-based edible Film. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 115, 647–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopermsub, P.; Mayen, V.; Warin, C. Nanoencapsulation of nisin and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid in niosomes and their antibacterial activity. J. Sci. Res. 2012, 4, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prombutara, P.; Kulwatthanasal, Y.; Supaka, N.; Sramala, I. Production of nisin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for sustained antimicrobial activity. Food Control 2012, 24, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcão, V.M.; Costa, C.I.; Matos, C.M.; Moutinho, C.G.; Amorim, M.; Pintado, M.E.; Gomes, A.P.; Vila, M.M.; Teixeira, J.A. Food hydrocolloids nanoencapsulation of bovine lactoferrin for food and biopharmaceutical applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 32, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.; Moreira, R.G.; Castell-Perez, E. Poly (DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) nanoparticles with entrapped trans-cinnamaldehyde and eugenol for antimicrobial delivery applications. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liolios, C.C.; Gortzi, O.; Lalas, S.; Tsaknis, J.; Chinou, I. Liposomal incorporation of carvacrol and thymol isolated from the essential oil of Origanum dictamnus L. and in vitro antimicrobial activity. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, H.H.; Sharoba, A.M.; El-Tanahi, H.H.; Morsy, M.K. Stability of antimicrobial activity of pullulan edible films incorporated with nanoparticles and essential oils and their impact on turkey deli meat quality. J. Food Dairy Sci. 2013, 4, 557–573. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.L.; Li, X.G.; Zhu, F.; Lei, C.L. Structural characterization of nanoparticles loaded with garlic essential oil and their insecticidal activity against Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10156–10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamil, B.; Abbasi, R.; Abbasi, S.; Imran, M.; Khan, S.U.; Ihsan, A.; Javed, S.; Bokhari, H. Encapsulation of cardamom essential oil in chitosan nano-composites: In-vitro efficacy on antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens and cytotoxicity studies. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghayempour, S.; Montazer, M.; Mahmoudi Rad, M. Tragacanth gum as a natural polymeric wall for producing antimicrobial nanocapsules loaded with plant extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 81, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, E.A.; Roy, T.; D’Adamo, C.R.; Wieland, L.S. Probiotics and gastrointestinal conditions: An overview of evidence from the Cochrane Collaboration. Nutrition 2018, 45, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemer, C.J.; Gibson, G.R. An overview of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in the functional food concept: Perspectives and future strategies. Int. Dairy J. 1998, 8, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espitia, P.J.P.; Batista, R.A.; Azeredo, H.M.C.; Otoni, C.G. Probiotics and their potential applications in active edible films and coatings. Food Res. Int. 2016, 90, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, G. Probiotics and prebiotics—Progress and challenges. Int. Dairy J. 2008, 18, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sheraji, S.H.; Ismail, A.; Manap, M.Y.; Mustafa, S.; Yusof, R.M.; Hassan, F.A. Prebiotics as functional foods: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1542–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floch, M.H. The role of prebiotics and probiotics in gastrointestinal disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 47, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalampopoulos, D.; Rastall, R.A. Prebiotics in foods. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanovska, T.P.; Mladenovska, K.; Zhivikj, Z.; Pavlova, M.J.; Gjurovski, I.; Ristoski, T.; Petrushevska-Tozi, L. Synbiotic loaded chitosan-Ca-alginate microparticles reduces inflammation in the TNBS model of rat colitis. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 527, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, K.; Godward, G.; Reynolds, N.; Arumugaswamy, R.; Peiris, P.; Kailasapathy, K. Encapsulation of probiotic bacteria with alginate–starch and evaluation of survival in simulated gastrointestinal conditions and in yoghurt. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000, 62, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B.; Gani, A.; Gani, A.; Shah, A.; Ahmad, F. Production of RS4 from rice starch and its utilization as an encapsulating agent for targeted delivery of probiotics. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyabama, S.; Ranjith, M.; Bruntha, P.; Vijayabharathi, R.; Brindha, V. LWT—Food science and technology co-encapsulation of probiotics with prebiotics on alginate matrix and its effect on viability in simulated gastric environment. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 57, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prisco, A.; Mauriello, G. Probiotication of foods: A focus on microencapsulation tool. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 48, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shori, A.B. Microencapsulation Improved Probiotics Survival During Gastric Transit. HAYATI J. Biosci. 2017, 24, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitake, D.; Kandasamy, S.; Bruntha, P. Food bioscience recent developments on encapsulation of lactic acid bacteria as potential starter culture in fermented foods—A review. Food Biosci. 2018, 21, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.J.; Lara-Villoslada, F.; Ruiz, M.A.; Morales, M.E. Microencapsulation of bacteria: A review of different technologies and their impact on the probiotic effects. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 27, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.T.; Tzortzis, G.; Charalampopoulos, D.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Microencapsulation of probiotics for gastrointestinal delivery. J. Control. Release 2012, 162, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otoni, C.G.; Espitia, P.J.P.; Avena-Bustillos, R.J.; Mchugh, T.H. Trends in antimicrobial food packaging systems: Emitting sachets and absorbent pads. FRIN 2016, 83, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, M.S.; Rojas-Graü, M.A.; Rodríguez, F.J.; Ramírez, J.; Carmona, A.; Martin-Belloso, O. Alginate- and Gellan-Based Edible Films for Probiotic Coatings on Fresh-Cut Fruits. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, E190–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi, B.; Mohammadi, R.; Rouhi, M.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Shojaee-Aliabadi, S.; Koushki, M.R. Survival of probiotic bacteria in carboxymethyl cellulose-based edible film and assessment of quality parameters. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 87, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.O.; Soares, J.; Monteiro, M.J.P.; Gomes, A.; Pintado, M. Impact of whey protein coating incorporated with Bi fi dobacterium and Lactobacillus on sliced ham properties. Meat Sci. 2018, 139, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, B.J.; Meng, X.H. Microencapsulation of lactobacillus bulgaricus and survival assays under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 29, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasani, A.C.; Shojaosadati, S.A. Pectin-non-starch nanofibers biocomposites as novel gastrointestinal-resistant prebiotics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 94, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oregel-Zamudio, E.; Angoa-Pérez, M.V.; Oyoque-Salcedo, G.; Aguilar-González, C.N.; Mena-violante, H.G. scientia horticulturae effect of candelilla wax edible coatings combined with biocontrol bacteria on strawberry quality during the shelf-life. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 214, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafe, A.; Etemadi, H.; Dilmaghani, A.; Reza, G. International journal of biological macromolecules investigation of pectin/starch hydrogel as a carrier for oral delivery of probiotic bacteria. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 97, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorasani, A.C.; Shojaosadati, S.A. Bacterial nanocellulose-pectin bionanocomposites as prebiotics against drying and gastrointestinal condition. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 83, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Mascaraque, L.G.; Morfin, R.C.; Pérez-Masiá, R.; Sanchez, G.; Lopez-Rubio, A. Optimization of electrospraying conditions for the microencapsulation of probiotics and evaluation of their resistance during storage and in-vitro digestion. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 69, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darjani, P.; Hosseini, M.; Kadkhodaee, R.; Milani, E. LWT—Food science and technology in fluence of prebiotic and coating materials on morphology and survival of a probiotic strain of Lactobacillus casei exposed to simulated gastrointestinal conditions. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersaneti, G.T.; Mantovan, J.; Magri, A.; Antonia, M.; Colabone, P. Edible films based on cassava starch and fructooligosaccharides produced by Bacillus subtilis natto CCT 7712. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 151, 1132–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odila Pereira, J.; Soares, J.; Sousa, S.; Madureira, A.R.; Gomes, A.; Pintado, M. Edible films as carrier for lactic acid bacteria. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukoulis, C.; Singh, P.; Macnaughtan, W.; Parmenter, C.; Fisk, I.D. Food hydrocolloids compositional and physicochemical factors governing the viability of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG embedded in starch-protein based edible films. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavera-Quiroz, M.J.; Romano, N.; Mobili, P.; Pinotti, A.; Gómez-Zavaglia, A.; Bertola, N. Green apple baked snacks functionalized with edible coatings of methylcellulose containing Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 16, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piermaria, J.; Diosma, G.; Aquino, C.; Garrote, G.; Abraham, A. Edible kefiran films as vehicle for probiotic microorganisms. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 32, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukoulis, C.; Behboudi-Jobbehdar, S.; Yonekura, L.; Parmenter, C.; Fisk, I.D. Stability of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in prebiotic edible films. Food Chem. 2014, 159, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soukoulis, C.; Yonekura, L.; Gan, H.; Behboudi-Jobbehdar, S.; Parmenter, C.; Fisk, I. Food hydrocolloids probiotic edible films as a new strategy for developing functional bakery products: The case of pan bread. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 39, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, N.; Tavera-Quiroz, M.J.; Bertola, N.; Mobili, P.; Pinotti, A.; Gómez-Zavaglia, A. Edible methylcellulose-based films containing fructo-oligosaccharides as vehicles for lactic acid bacteria. Food Res. Int. 2014, 64, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandansamy, K.; Somasundaram, P.D. Microencapsulation of colors by spray drying-A review microencapsulation of colors by spray drying—A review. Int. J. Food Eng. 2012, 8, 1556–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfat, Y.A.; Ahmed, J.; Hiremath, N.; Auras, R.; Joseph, A. Thermo-mechanical, rheological, structural and antimicrobial properties of bionanocomposite films based on fish skin gelatin and silver-copper nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 62, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, G.; Bilek, S.E. Microencapsulation of natural food colourants Applied to Natural Food Colourants. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 3, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, N.; Pola, C.C.; Teixeira, B.N.; Hill, L.E.; Bayrak, A.; Gomes, C.L. Preparation of black pepper oleoresin inclusion complexes based on beta-cyclodextrin for antioxidant and antimicrobial delivery applications using kneading and freeze drying methods: A comparative study. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 91, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reza, R.M.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D.; Del Real-López, A.; Piñon-Segundo, E.; Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.L. Effect of sucrose concentration and pH onto the physical stability of β-carotene nanocapsules. LWT 2018, 90, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Li, Z.; Liang, H.; Shi, M.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.; et al. Controlled release of anthocyanins from oxidized konjac glucomannan microspheres stabilized by chitosan oligosaccharides. Food Hydrocolld. 2015, 51, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanfar, R.; Tamaddon, A.M.; Niakousari, M.; Moein, M.R. Preservation of anthocyanins in solid lipid nanoparticles: Optimization of a microemulsion dilution method using the Placket-Burman and Box-Behnken designs. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, P.P.; Paese, K.; Guterres, S.S.; Pohlmann, A.R.; Jablonski, A.; Flôres, S.H.; de Oliveira Rios, A. Stability study of lycopene-loaded lipid-core nanocapsules under temperature and photosensitization. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 71, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.L.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D.; Del Real, A.; Piñon-Segundo, E.; Zambrano-Zaragoza, J.F. The release kinetics of β-carotene nanocapsules/xanthan gum coating and quality changes in fresh-cut melon (cantaloupe). Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ersus Bilek, S.; Yılmaz, F.M.; Özkan, G. The effects of industrial production on black carrot concentrate quality and encapsulation of anthocyanins in whey protein hydrogels. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 102, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Fu, Y.; Chen, G.; Shi, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Shen, Y. Fabrication and characterization of carboxymethyl chitosan and tea polyphenols coating on zein nanoparticles to encapsulate β-carotene by anti-solvent precipitation method. Food Hydrocolld. 2017, 77, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, E.; Fabra, M.J.; Martínez-Sanz, M.; Gomez-Mascaraque, L.G.; Altan, A.; Lopez-Rubio, A. Development and characterization of chitosan/gelatin electrosprayed microparticles as food grade delivery vehicles for anthocyanin extracts. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 77, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.; Takhistov, P.; McClements, D.J. Functional materials in food nanotechnology. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, R107–R116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munhuweyi, K.; Caleb, O.J.; van Reenen, A.J.; Opara, U.L. Physical and antifungal properties of β-cyclodextrin microcapsules and nanofibre films containing cinnamon and oregano essential oils. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 87, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampau, A.; González-Martinez, C.; Chiralt, A. Carvacrol encapsulation in starch or PCL based matrices by electrospinning. J. Food Eng. 2017, 214, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Pérez, M.J.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D.; de los Ángeles Cornejo-Villegas, M.; de la Luz Zambrano-Zaragoza, M. Optimization of the emulsification-diffusion method using ultrasound to prepare nanocapsules of different food-core oils. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 87, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaei, A.; Hadian, M.; Mohsenifar, A.; Rahmani-Cherati, T.; Tabatabaei, M. A coating based on clove essential oils encapsulated by chitosan-myristic acid nanogel efficiently enhanced the shelf-life of beef cutlets. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2017, 14, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karathanos, V.T.; Mourtzinos, I.; Yannakopoulou, K.; Andrikopoulos, N.K. Study of the solubility, antioxidant activity and structure of inclusion complex of vanillin with β-cyclodextrin. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joana Gil-Chávez, G.; Villa, J.A.; Fernando Ayala-Zavala, J.; Basilio Heredia, J.; Sepulveda, D.; Yahia, E.M.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Technologies for Extraction and Production of Bioactive Compounds to be Used as Nutraceuticals and Food Ingredients: An Overview. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiari, S.; Choulitoudi, E.; Oreopoulou, V. Edible and active films and coatings as carriers of natural antioxidants for lipid food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbettaïeb, N.; Tanner, C.; Cayot, P.; Karbowiak, T.; Debeaufort, F. Impact of functional properties and release kinetics on antioxidant activity of biopolymer active films and coatings. Food Chem. 2018, 242, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-López, M.L.; Cerqueira, M.A.; de Rodríguez, D.J.; Vicente, A.A. Perspectives on Utilization of Edible Coatings and Nano-laminate Coatings for Extension of Postharvest Storage of Fruits and Vegetables. Food Eng. Rev. 2016, 8, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Jung, J.; Simonsen, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Cellulose nanocrystal reinforced chitosan coatings for improving the storability of postharvest pears under both ambient and cold storages. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.L.; Mercado-Silva, E.; Del Real L., A.; Gutiérrez-Cortez, E.; Cornejo-Villegas, M.A.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D. The effect of nano-coatings with α-tocopherol and xanthan gum on shelf-life and browning index of fresh-cut “red Delicious” apples. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2014, 22, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hernández, G.B.; Amodio, M.L.; Colelli, G. Carvacrol-loaded chitosan nanoparticles maintain quality of fresh-cut carrots. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 41, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Xiao, Z.; Zhou, R.; Feng, N. Production of a transparent lavender flavour nanocapsule aqueous solution and pyrolysis characteristics of flavour nanocapsule. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 52, 4607–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, L.E.; Oliveira, D.A.; Hills, K.; Giacobassi, C.; Johnson, J.; Summerlin, H.; Taylor, T.M.; Gomes, C.L. A comparative study of natural antimicrobial delivery systems for microbial safety and quality of fresh-cut lettuce. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umagiliyage, A.L.; Becerra-Mora, N.; Kohli, P.; Fisher, D.J.; Choudhary, R. Antimicrobial efficacy of liposomes containing D-limonene and its effect on the storage life of blueberries. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 128, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De León-Zapata, M.A.; Pastrana-Castro, L.; Barbosa-Pereira, L.; Rua-Rodríguez, M.L.; Saucedo, S.; Ventura-Sobrevilla, J.M.; Salinas-Jasso, T.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Aguilar, C.N. Nanocoating with extract of tarbush to retard Fuji apples senescence. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 134, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Pacheco, Z.N.; Bautista-Baños, S.; Valle-Marquina, M.Á.; Hernández-López, M. The effect of nanostructured chitosan and chitosan-thyme essential oil coatings on Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Growth in vitro and on cv Hass Avocado and Fruit Quality. J. Phytopathol. 2017, 165, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, H.M.C.; Miranda, K.W.E.; Ribeiro, H.L.; Rosa, M.F.; Nascimento, D.M. Nanoreinforced alginate-acerola puree coatings on acerola fruits. J. Food Eng. 2012, 113, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hernández-Hernández, E.; Lira-Moreno, C.Y.; Guerrero-Legarreta, I.; Wild-Padua, G.; Di Pierro, P.; García-Almendárez, B.E.; Regalado-González, C. Effect of nanoemulsified and microencapsulated mexican oregano (Lippia graveolens Kunth) essential oil coatings on quality of fresh pork meat. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogvar, O.B.; Saba, M.K.; Emamifar, A.; Hallaj, R. Influence of nano-ZnO on microbial growth, bioactive content and postharvest quality of strawberries during storage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 35, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, E.A.; Dağtekin, B.B.; Türe, M.; Yeşilsu, A.F.; Torres-Giner, S. Quality improvement of rainbow trout fillets by whey protein isolate coatings containing electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone) nanofibers with Urtica dioica L. extract during storage. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 78, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, O.L.; Pereira, R.N.; Martins, A.; Rodrigues, R.; Fuciños, C.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pastrana, L.; Xavier Malcata, F.; Vicente, A.A.; Fuci, C.; et al. Design of whey protein nanostructures for incorporation and release of nutraceutical compounds in food. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1377–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, N. Transport and release in nano-carriers for food applications. J. Food Eng. 2016, 175, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirós-Sauceda, A.E.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Olivas, G.I.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Edible coatings as encapsulating matrices for bioactive compounds: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 1674–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, S.; Murthy, P.N.; Nath, L.; Chowdhury, P. Kinetic modeling on drug release from controlled drug delivery systems. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2010, 67, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acevedo-Fani, A.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Martín-Belloso, O. Nanostructured emulsions and nanolaminates for delivery of active ingredients: Improving food safety and functionality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 60, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N.A.; Narasimhan, B. Mathematical models in drug delivery: How modeling has shaped the way we design new drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]