Compared Corrosion Resistance of 430 Ferritic Stainless Steels Produced via Unidirectional and Reversible Rolling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation

2.2. Microstructural Characterization

2.3. Electrochemical Testing and Corrosion Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructure

3.2. Electrochemical Characterization

3.3. Corrosion Morphology

4. Conclusions

- (1).

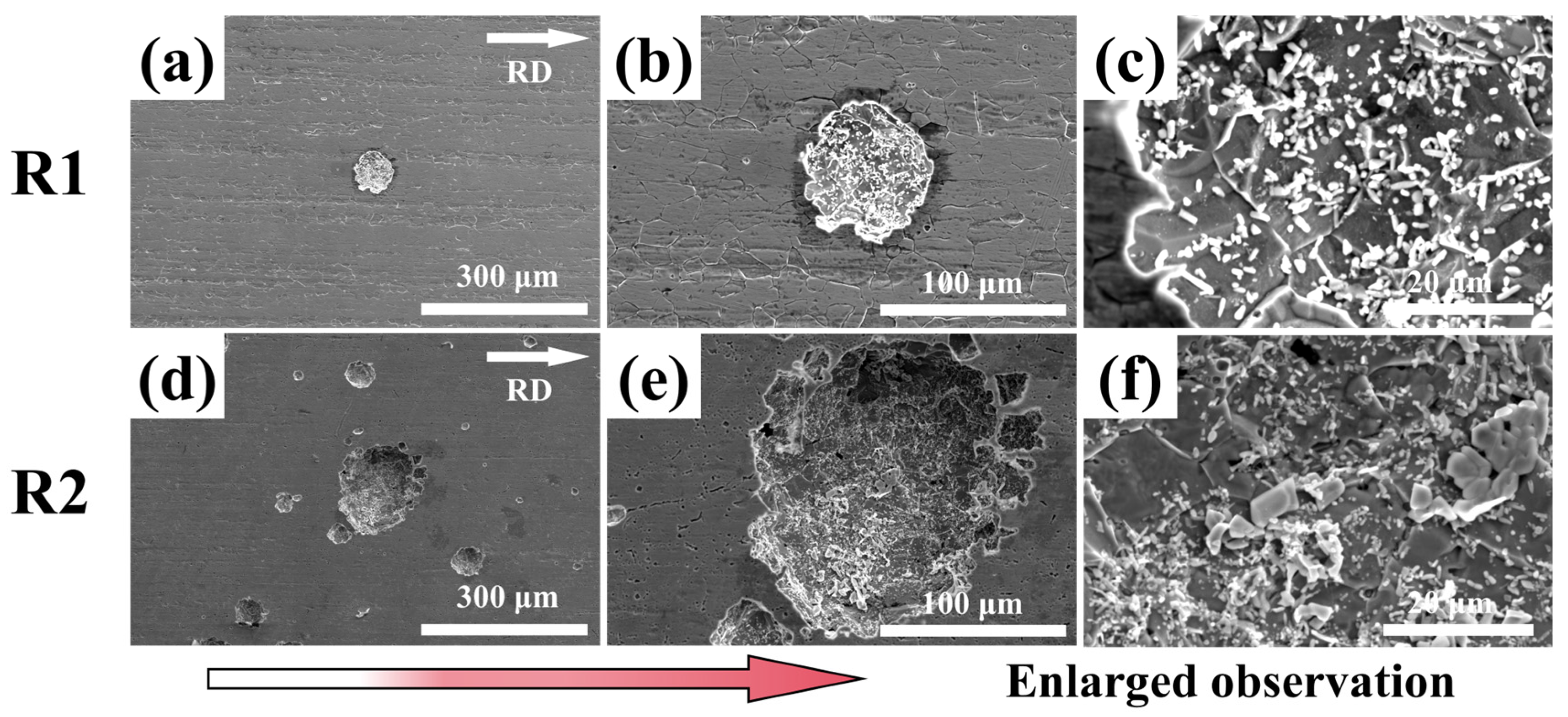

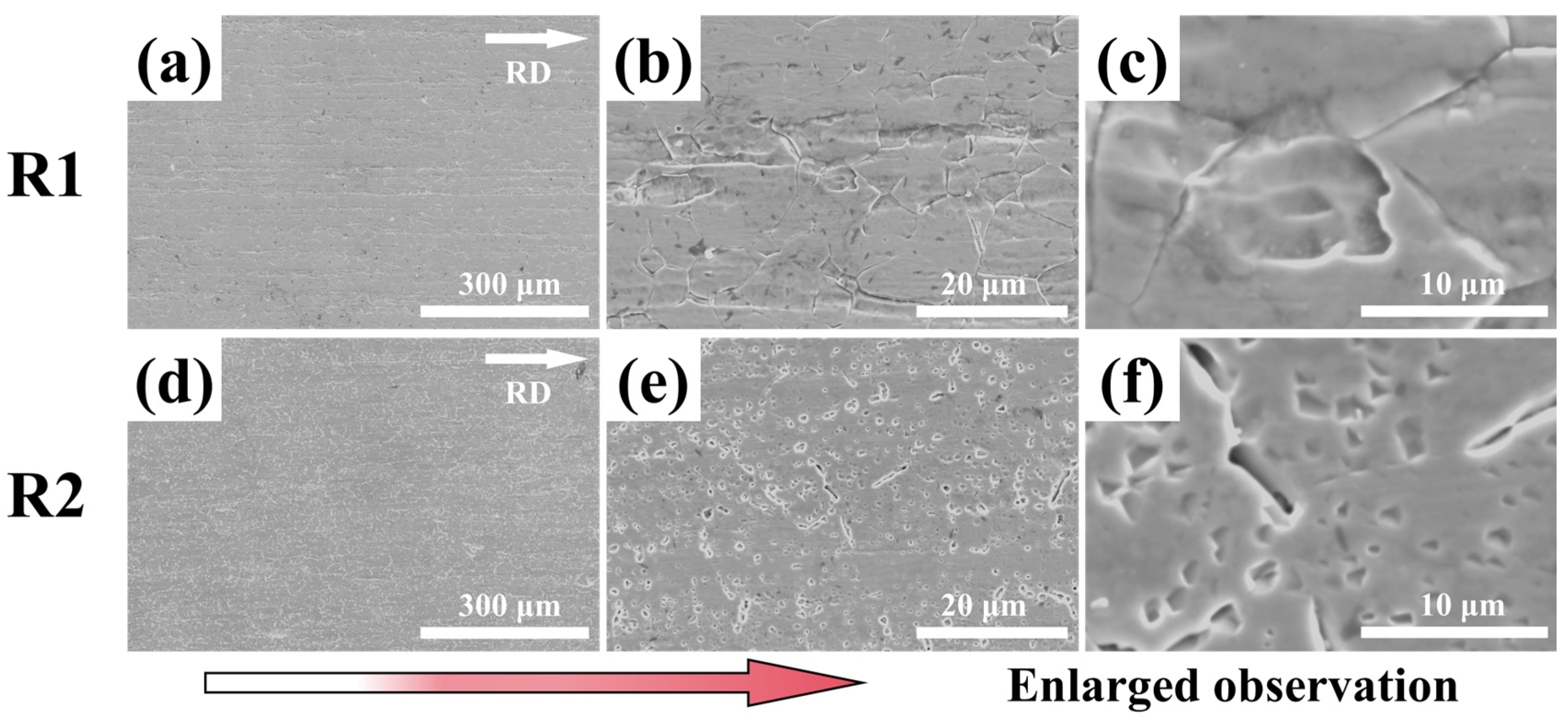

- Unidirectional rolling (R1) promotes strong interfacial bonding between MC carbides and the ferrite matrix, forming a compact microstructure with aligned carbide bands. Conversely, reversible rolling (R2) induces cyclic stress release, weakening particle-matrix interfaces and triggering widespread particle detachment, thereby generating a porous surface morphology characterized by deep voids and pits.

- (2).

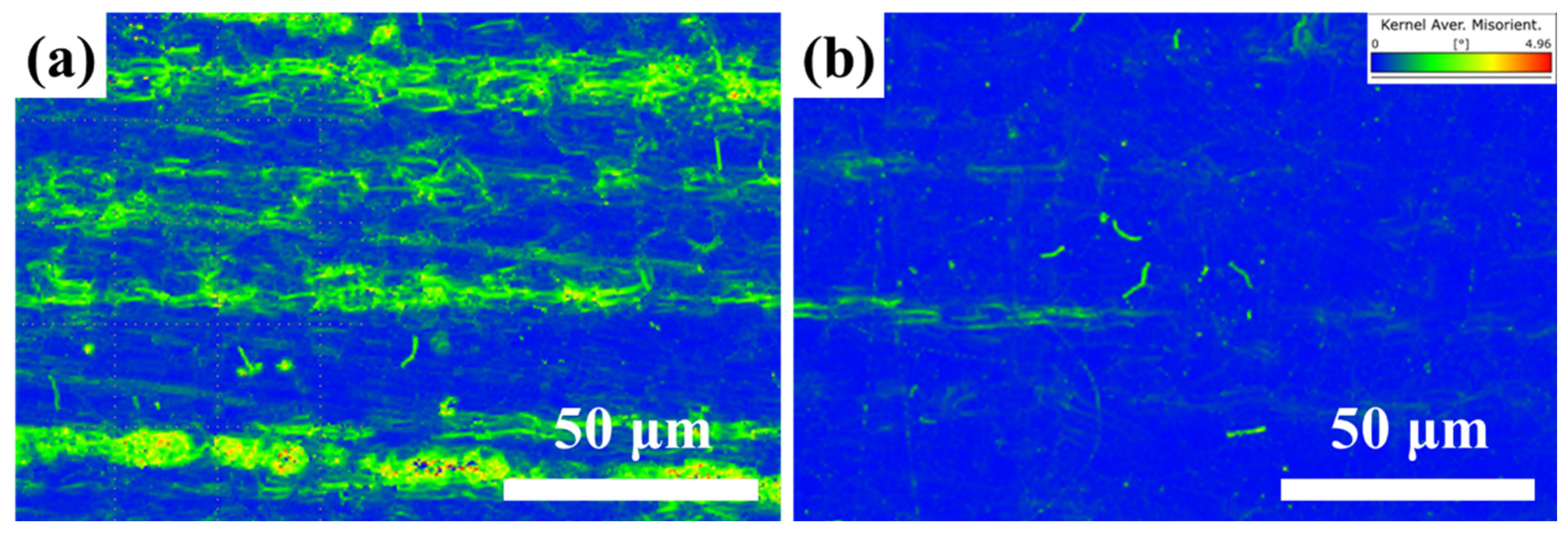

- Although the R1 sample exhibits higher residual stress (validated by KAM mapping), it demonstrates superior long-term corrosion resistance in immersion/EIS tests due to its dense microstructure. This contrasts with the lower stress state of the R2 sample but severe localized corrosion, proving that surface porosity—not residual stress—is the dominant factor accelerating corrosion damage by facilitating passive film breakdown.

- (3).

- The void-rich structure in the R2 sample (from particle detachment) acts as preferential corrosion initiation sites. Salt spray testing confirms elongated pits along grain boundaries and dense intra-granular pitting, directly correlating with carbide distribution and pore locations. This morphology accelerates anodic dissolution and undermines surface film stability, reducing corrosion resistance compared to R1 sample.

- (4).

- Unidirectional rolling enhances corrosion resistance by preserving microstructural coherence, while reversible rolling sacrifices integrity for stress relaxation. This work establishes that optimizing interfacial bonding strength—not merely minimizing residual stress—is critical for high-corrosion-resistance applications. The findings provide a mechanistic basis for tailoring rolling process in stainless steel manufacturing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thanedburapasup, S.; Wetchirarat, N.; Muengjai, A.; Tengprasert, W.; Wiman, P.; Thublaor, T.; Uawongsuwan, P.; Siripongsakul, T.; Chandra-ambhorn, S. Fabrication of Mn–Co Alloys Electrodeposited on AISI 430 Ferritic Stainless Steel for SOFC Interconnect Applications. Metals 2023, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Kesler, O. Evaluation of Pore-Former Size and Volume Fraction on Tape Cast Porous 430 Stainless Steel Substrates for Plasma Spraying. Materials 2024, 17, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnegren, P.; Sattari, M.; Svensson, J.E.; Froitzheim, J. Temperature dependence of corrosion of ferritic stainless steel in dual atmosphere at 600−800 °C. J. Power Sources 2018, 392, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashell, K.A.; Baddoo, N.R. Ferritic stainless steels in structural applications. Thin-Walled Struct. 2014, 83, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya Dolores, B.; Ruiz Flores, A.; Núñez Galindo, A.; Calvino Gámez, J.J.; Almagro, J.F.; Lajaunie, L. Textural, Microstructural and Chemical Characterization of Ferritic Stainless Steel Affected by the Gold Dust Defect. Materials 2023, 16, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.Q.; Xu, R.H.; Bi, H.Y.; Zhang, Z.X.; Chen, Z.Q.; Li, M.C.; Chen, B. The corrosion properties of ferritic stainless steel with varying Cr and Mo contents in the early stages of a simulated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environment investigated using experimental and joint calculation method HKD. Corros. Sci. 2024, 239, 112389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.R.; Martin, T.L.; Flewitt, P.E.J. Stress Corroison Cracking in Stainless Steels. Compr. Struct. Integr. 2023, 6, 163–200. Available online: https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/en/publications/stress-corrosion-cracking-in-stainless-steels/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Kim, J.K.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, K.Y. Influence of Cr, C and Ni on intergranular segregation and precipitation in Ti-stabilized stainless steels. Scr. Mater. 2010, 63, 449–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Cui, K.; Du, X.; Wu, Y. Effect of Nb addition on the microstructure and corrosion resistance of ferritic stainless steel. Appl. Phys. A 2020, 126, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Han, E.-H.; Liu, X. Atomic-scale evidence for the intergranular corrosion mechanism induced by co-segregation of low-chromium ferritic stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 2021, 189, 109588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.W.; Cheng, Y.H.; Wang, Z.H.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, M.M.; Zhang, R.Y.; Hou, B.R. Origin of the pitting corrosion in the as-rolled and annealed ferritic stainless steel in 3.5wt.% NaCl solution. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 520, 145899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.-Y.; Kim, K.-W.; Park, S.-J.; Lee, T.-H.; Park, H.; Moon, J.; Hong, H.-U.; Lee, C.-H. Effects of Cr on pitting corrosion resistance and passive film properties of austenitic Fe-19Mn-12Al-1.5 C lightweight steel. Corros. Sci. 2022, 206, 110529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Precipitation of sigma phase in duplex stainless steel and recent development on its detection by electrochemical potentiokinetic reactivation: A review. Corros. Commun. 2021, 2, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Asami, K.; Kawashima, A.; Habazaki, H.; Akiyama, E. The role of corrosion-resistant alloying elements in passivity. Corros. Sci. 2007, 49, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Seo, H.S.; Kim, K.Y. Alloy design to prevent intergranular corrosion of low-Cr ferritic stainless steel with weak carbide formers. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, C412–C418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y.G.; Li, H.Y.; Zhao, G.H.; Song, Y.H.; Xu, H. Influence of homogenized annealing on the intergranular corrosion behavior of super ferritic stainless steel S44660. Corros. Sci. 2025, 247, 112783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiyan, S.; Bianco, M.; El-Kharouf, A.; Tomov, R.I.; Steinberger-Wilckens, R. Evaluation of inkjet-printed spinel coatings on standard and surface nitrided ferritic stainless steels for interconnect application in solid oxide fuel cell devices. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 20456–20466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.W.; Xu, X.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, G.Y.; Yan, H. Preparation of high corrosion resistant solar absorbing coating on the surface of ferritic stainless steel by utilizing chemical coloring. Mater. Lett. 2020, 270, 127628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaigan, N.; Qu, W.; Ivey, D.G.; Chen, W.X. A review of recent progress in coatings, surface modifications and alloy developments for solid oxide fuel cell ferritic stainless steel interconnects. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 1529–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Zhong, N.; Dai, N.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y. Intergranular corrosion behavior and mechanism of the stabilized ultra-pure 430LX ferritic stainless steel. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 1787–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Sun, L.; Dai, N.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y. Investigation on ultra-pure ferritic stainless steel 436L susceptibility to intergranular corrosion using optimised double loop electrochemical potentiokinetic reactivation method. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammadi, H.; Jamaati, R. Effect of cold single-roll drive rolling on the microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of ferritic stainless steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 2679–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.Y.; Lu, H.H.; Xing, Z.Z.; Han, J.S.; Zhang, S.H.; Li, J.C. Effects of Al additions on precipitation, recrystallization and mechanical properties of hot-rolled ultra-super ferritic stainless steels. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 4278–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, B.G.; Lei, L.L.; Wang, X.Y.; He, P.; Yuan, X.Z.; Dai, W.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.M.; Sun, Y.T. Effects of grain boundary characteristics changing with cold rolling deformation on intergranular corrosion resistance of 443 ultra-pure ferritic stainless steel. Corros. Commun. 2022, 8, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, S.; Muto, I.; Sugawara, Y.; Hara, N. Pit initiation on sensitized Type 304 stainless steel under applied stress: Correlation of stress, Cr-depletion, and inclusion dissolution. Corros. Sci. 2020, 167, 108506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, S.; Muto, I.; Sugawara, Y.; Hara, N. The role of applied stress in the anodic dissolution of sulfide inclusions and pit initiation of stainless steels. Corros. Sci. 2021, 183, 109312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Lin, B.; Tang, J.L.; Zheng, H.P.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.L.; Kuang, Y.; Sun, X.M. Effect of elastic tensile stress on the pitting corrosion mechanism and passive film of 2205 duplex stainless steel. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 47, 143765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Fei, R.S.; Sun, F.; Bi, H.Y.; Chang, E.; Li, M.S. Effect of cold rolling deformation on the pitting corrosion behavior of high-strength metastable austenitic stainless steel 14Cr10Mn in simulated coastal atmospheric environments. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaie, D.; Moayed, M.H. Pitting corrosion of cold rolled solution treated 17-4 PH stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 2014, 80, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.M.; Zhou, C.S.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Hong, Y.J.; Zheng, J.Y.; Zhang, L. Anomalous evolution of corrosion behaviour of warm-rolled type 304 austenitic stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 2019, 154, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; Yuan, Z.; Tan, Z.; Yu, W. Precipitation mechanisms and crystallographic study of co-precipitation carbides in super austenitic stainless steel. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1036, 181942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Ma, X.; Chen, B. Interfacial Microstructure and Cladding Corrosion Resistance of Stainless Steel/Carbon Steel Clad Plates at Different Rolling Reduction Ratios. Metals 2025, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.S.; Dai, Q.; Wang, D.S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Li, C.Q. Insight into the enhancing mechanical strength of CoCrNi-TiC composites fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 924, 147786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordbar-Khiabani, A.; Gasik, M. Electrochemical and biological characterization of Ti–Nb–Zr–Si alloy for orthopedic applications. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagarinec, D.; Gubeljak, N. Effect of Residual Stresses on the Fatigue Stress Range of a Pre-Deformed Stainless Steel AISI 316L Exposed to Combined Loading. Metals 2024, 14, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojai, S.; Schönamsgruber, F.; Köhler, M.; Ghafoori, E. Impact of accelerated corrosion on weld geometry, hardness and residual stresses of offshore steel joints over time. Mater. Des. 2025, 251, 113578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Yoo, Y.-R.; Kim, Y.-S. Effect of Ultrasonic Nanocrystalline Surface Modification (UNSM) on Stress Corrosion Cracking of 304L Stainless Steel. Metals 2024, 14, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Fe | Cr | Al | Co | Cu | Mn | Ni | O | Si |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 430 | Bal. | 16-18 | / | / | / | 1 | 0.75 | / | 1 |

| R1 | Bal. | 16.22 | 0.003 | 0.031 | 0.080 | 0.313 | 0.183 | 0.008 | 0.385 |

| R2 | Bal. | 15.96 | 0.003 | 0.030 | 0.075 | 0.275 | 0.116 | 0.012 | 0.362 |

| Sample | R1 | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test Direction | TD | RD | TD | RD |

| Maximum value of compressive stress σmax(MPa) | −52.81 | −72.11 | −21.37 | −52.05 |

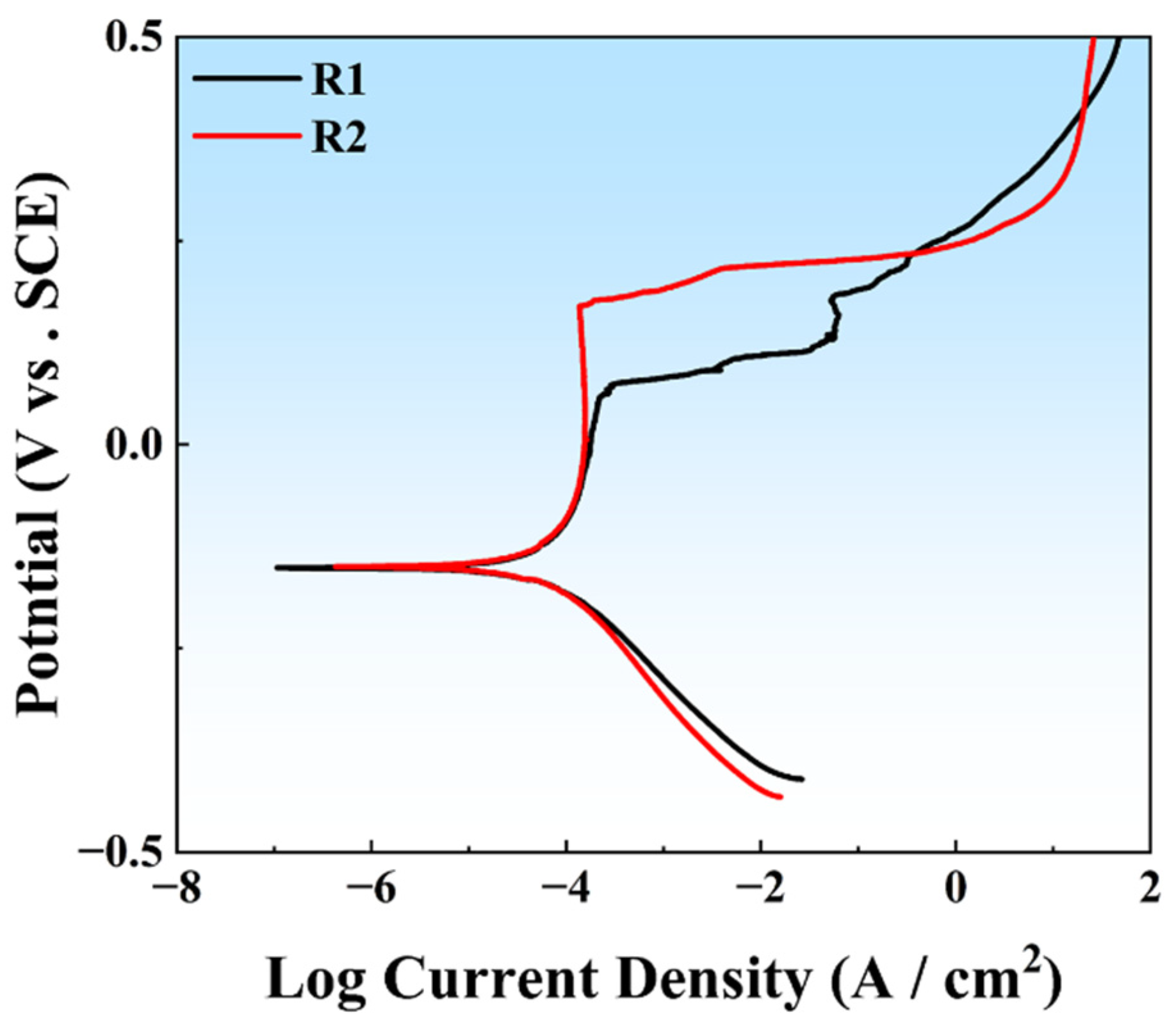

| Ecorr (mV/SCE) | icorr (μA/cm2) | Eb (mV/SCE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | −151.319 | 0.075 | 169.691 |

| R2 | −149.677 | 0.078 | 58.412 |

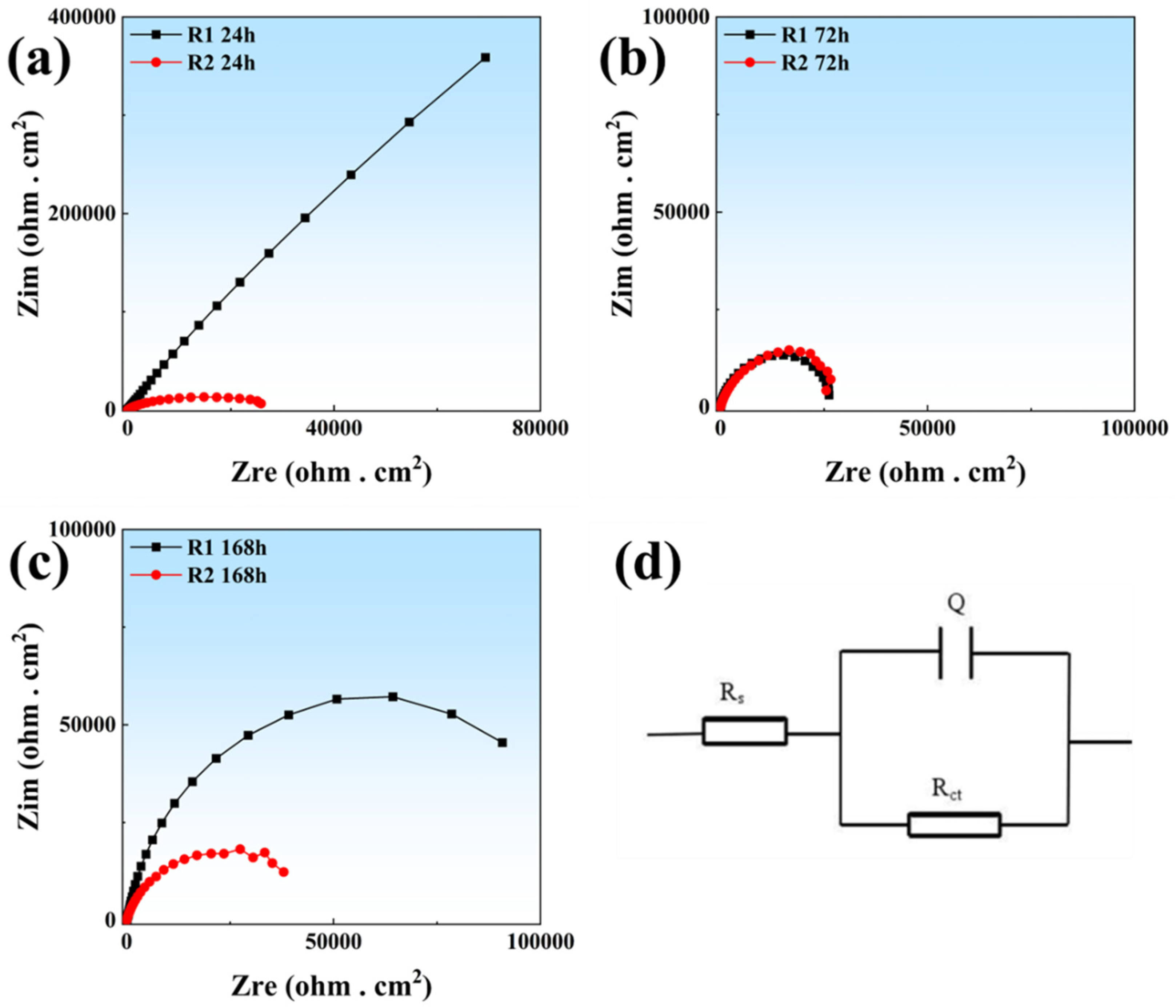

| Sample | Rs (Ω cm2) | Ydl (Ω−1 cm−2 sn) | ndl | Rt (Ω cm2) | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1-24 h | 16.42 | 3.304 × 10−5 | 0.8936 | 1.171 × 108 | 2.192 × 10−3 |

| R1-168 h | 15.48 | 6.692 × 10−5 | 0.8903 | 1.386 × 104 | 1.396 × 10−3 |

| R2-24 h | 7.42 | 9.293 × 10−5 | 0.8387 | 3.261 × 104 | 1.447 × 10−3 |

| R2-168 h | 7.44 | 8.028 × 10−5 | 0.8000 | 4.484 × 103 | 7.761 × 10−4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Yin, H.; Zhao, X.; Guo, S. Compared Corrosion Resistance of 430 Ferritic Stainless Steels Produced via Unidirectional and Reversible Rolling. Coatings 2026, 16, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010057

Yang L, Zhang B, Wang Z, Yin H, Zhao X, Guo S. Compared Corrosion Resistance of 430 Ferritic Stainless Steels Produced via Unidirectional and Reversible Rolling. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Liming, Bo Zhang, Ziwei Wang, Hongmei Yin, Xiong Zhao, and Shuainan Guo. 2026. "Compared Corrosion Resistance of 430 Ferritic Stainless Steels Produced via Unidirectional and Reversible Rolling" Coatings 16, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010057

APA StyleYang, L., Zhang, B., Wang, Z., Yin, H., Zhao, X., & Guo, S. (2026). Compared Corrosion Resistance of 430 Ferritic Stainless Steels Produced via Unidirectional and Reversible Rolling. Coatings, 16(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010057