1. Introduction

Stainless steel, especially SUS304, is widely used in various industrial fields such as machinery, electronics, and construction parts manufacturing due to its excellent corrosion resistance derived from the formation of a chromium oxide–based passive film on the surface [

1]. However, mechanical and thermal processing, such as rolling or polishing, can locally damage this passive film, creating micro-defects that serve as initiation sites for localized corrosion, particularly in chloride-rich environments such as seawater [

2,

3,

4]. Although complete prevention of corrosion is impractical, developing effective surface coating strategies to slow down corrosion progression is essential for improving the durability and lifetime of metallic components. Oxide-based protective coatings such as Al

2O

3, TiO

2, SiO

2, and ZrO

2 have been widely studied for their chemical stability and barrier properties [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Conventional physical vapor deposition (PVD) techniques, including magnetron sputtering and pulsed laser deposition, have been employed to synthesize such coatings; however, these methods rely on a line-of-sight deposition mechanism, making it difficult to achieve conformal, defect-free passivation films. Moreover, PVD-deposited films often exhibit columnar grain structures, and these grain boundaries can act as fast diffusion pathways for corrosive ions, thereby compromising the protective function of the coating [

9,

10]. To overcome these limitations, atomic layer deposition (ALD) has emerged as a promising technique for forming highly conformal, pinhole-free thin films through self-limiting surface reactions by sequentially exposing the substrate surface to precursor and reactant gases. ALD offers precise thickness control at the nanometer scale, excellent step coverage on complex surface geometries, and scalability for large-area substrates, making it particularly suitable for synthesizing protective coatings in industrial sectors such as marine construction [

11]. ALD corrosion-protective coatings can achieve enhanced corrosion resistance not only through single-layer barrier films but also by forming nanolaminate structures composed of alternately stacked different materials. In particular, ALD nanolaminate structures increase the tortuosity of ion diffusion pathways and suppress crack propagation throughout the coating, resulting in improved long-term corrosion resistance compared with single-layer films [

12,

13]. However, most previous studies have primarily focused on variations in the number of stacking layers in nanolaminate coatings at a fixed total thickness, changes in the total film thickness, or the general effects of introducing nanolaminate structures [

10,

12,

13]. Therefore, a more in-depth understanding of the role of each individual layer is required for the rational design of ALD nanolaminate corrosion-protective coatings.

In this study, single-layer Al

2O

3, ZrO

2, and Al

2O

3/ZrO

2 nanolaminate coatings were deposited on SUS304 stainless steel substrates using ALD to improve corrosion resistance in saline environments. Amorphous Al

2O

3 acts as a dense chemical barrier that effectively blocks the penetration of corrosive ions. Meanwhile, ZrO

2 is thermodynamically compatible with Al

2O

3, forming no compounds between the two oxides according to the phase diagram, thereby ensuring excellent interfacial stability and structural integrity of the laminated structure [

14]. By alternately stacking these layers, a nanoscale lamination structure was fabricated to enhance protection performance. In particular, by maintaining an identical total film thickness and a fixed number of laminate repetitions while selectively varying only the thickness of individual Al

2O

3 and ZrO

2 sublayers, this study aims to elucidate how thickness-dependent crystallization behavior within the internal sublayers influences ion diffusion pathways and, ultimately, corrosion resistance. This approach provides a differentiated and mechanistic understanding of structure–property relationships in nanolaminate corrosion barrier coatings.

3. Results and Discussion

First, the self-limiting surface reactions in the ALD process were ensured by optimizing the pulse durations for each precursor and reactant at a growth temperature of 250 °C (

Figure 2). All experiments were performed using films deposited on 6-inch Si wafers, and the film thicknesses were measured using spectroscopic ellipsometry.

Figure 2a shows the growth rate of Al

2O

3 films as a function of TMA precursor pulse time. The TMA pulse duration was increased from 0.3 s to 0.5 s, while the purge and reactant pulse times were set to 15 s (N

2 purge) and 0.5 s (H

2O injection), respectively, to ensure sufficient surface reactions. When the TMA pulse time exceeded 0.3 s, the growth rate of Al

2O

3 thin films was saturated at 0.11 nm/cycle, indicating that the self-limiting adsorption reaction of TMA was stabilized beyond 0.3 s. Similarly, the effect of the H

2O reactant pulse time was examined, as shown in

Figure 2b. The purge time was fixed at 15 s, and the TMA pulse duration was set to 0.3 s, as determined from

Figure 2a. When the H

2O pulse exceeded 0.3 s, the growth rate of Al

2O

3 thin films was also saturated at 0.11 nm/cycle, indicating that the ligand exchange reaction between the chemisorbed TMA and H

2O was completed beyond 0.3 s. Thus, the saturated growth rate of Al

2O

3 thin film was confirmed to be 0.11 nm/cycle at 250 °C. Under these conditions, the refractive index of Al

2O

3 was measured to be 1.65. Next, the optimization of the ALD-ZrO

2 process was confirmed, as shown in

Figure 2c,d.

Figure 2c shows the variation in the growth rate of ZrO

2 films as a function of the TEMAZr precursor pulse time. The purge and reactant pulse times were set to 30 s (N

2 purge) and 2 s (H

2O injection), respectively, to allow sufficient surface reactions. When the TEMAZr pulse time exceeded 2 s, the growth rate of ZrO

2 films was saturated at ~0.08 nm/cycle, confirming that the self-limiting adsorption of TEMAZr was achieved beyond this duration.

Figure 2d shows the variation in the growth rate of ZrO

2 films as a function of H

2O reactant pulse time. The purge time was fixed at 30 s, and the TEMAZr pulse time was set to 2 s based on the optimized condition shown in

Figure 2c. The saturated growth rate of ~0.08 nm/cycle was obtained when the H

2O pulse exceeded 1 s. Thus, the saturated growth rate of ZrO

2 film was confirmed to be 0.08 nm/cycle at 250 °C, with a corresponding refractive index of 2.13. Thus, the self-limiting reactions in the ALD-Al

2O

3 and ALD-ZrO

2 were clearly confirmed. In addition, both ALD-Al

2O

3 and ALD-ZrO

2 films exhibited high thickness uniformity (~95%) on 6-inch Si wafers under these optimized ALD conditions. After then, single-layer Al

2O

3, single-layer ZrO

2, and three types of Al

2O

3/ZrO

2 nanolaminate films with different thickness ratios ([Al

2O

3 (3 nm)/ZrO

2 (15 nm)] × 3, [Al

2O

3 (9 nm)/ZrO

2 (9 nm)] × 3, and [Al

2O

3 (15 nm)/ZrO

2 (3 nm)] × 3) were prepared based on the optimized ALD processes for Al

2O

3 and ZrO

2. To enable a fair comparison by eliminating the influence of film thickness on corrosion behavior, the total thickness of all films was maintained at approximately 54 nm. Considering the confirmed growth rates of ALD-Al

2O

3 and ALD-ZrO

2, the thicknesses of the individual Al

2O

3 and ZrO

2 layers constituting the laminated films were controlled by independently adjusting the number of ALD-Al

2O

3 and ALD-ZrO

2 cycles, respectively.

To investigate the crystallinity of the films deposited on SUS304, XRD analysis was performed in the 2θ range of 20°–80° using a fixed incidence angle of θ = 1°. The obtained XRD patterns are shown in

Figure 3. Diffraction peaks originating from the SUS304 substrate appeared at 2θ = 43.58°, 50.79°, and 74.69°, corresponding to the (111), (200), and (220) planes of austenitic stainless steel, respectively, in good agreement with the reference Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS) card (No. 33-0397). The single-layer Al

2O

3 film deposited on SUS304 exhibited a typical amorphous structure, with no distinct diffraction peaks attributable to Al

2O

3. In contrast, the single-layer ZrO

2 film-coated SUS304 exhibited clear diffraction peaks in addition to those from the substrate, observed at 2θ = 30.27°, 34.81°, 35.26°, 50.37°, and 60.21°. These peaks correspond to the (011), (002), (110), (112), and (121) planes of tetragonal ZrO

2 (JCPDS card No. 50-1089), respectively. For the nanolaminate film-coated samples, distinct crystallization behaviors were observed for some samples depending on the individual ZrO

2 layer thicknesses (3, 9, and 15 nm) within the laminated structure. In the [Al

2O

3 (15 nm)/ZrO

2 (3 nm)] × 3 nanolaminate film-coated sample, the microstructure remained amorphous without any detectable diffraction peaks, indicating that both the 3 nm-thick ZrO

2 layers as well as the 15 nm-thick Al

2O

3 layers exhibited amorphous structures. Similarly, in the [Al

2O

3 (9 nm)/ZrO

2 (9 nm)] × 3 nanolaminate film-coated sample, no distinct diffraction peaks were observed, indicating that both the ZrO

2 and the Al

2O

3 layers remained amorphous. However, in the Al

2O

3 [(3 nm)/ZrO

2 (15 nm)] × 3 nanolaminate film-coated sample, the XRD pattern exhibited clear diffraction peaks similar to those of the single-layer ZrO

2 film. A prominent peak appeared at 2θ = 30.27°, accompanied by several additional weaker peaks corresponding to the planes of tetragonal ZrO

2. These results suggest that when the individual ZrO

2 layer thickness reaches 15 nm, the film exceeds the critical thickness required for crystallization.

To clearly reveal the detailed microstructure, the cross-sectional microstructure and elemental distribution of the thin films were examined using HRTEM.

Figure 4 shows the cross-sectional HRTEM images of the films along with their corresponding FFT patterns and EDS elemental mapping results.

Figure 4a presents the cross-sectional image of the [Al

2O

3 (15 nm)/ZrO

2 (3 nm)] × 3 nanolaminate film. The results show that an Al

2O

3 layer with a thickness of ~15.3 nm and a ZrO

2 layer with a thickness of ~3.2 nm were uniformly deposited, forming a well-defined laminated structure. In the corresponding FFT image (

Figure 4a′), a diffused halo pattern indicates a typical amorphous structure. The corresponding EDS elemental mapping obtained from the same [Al

2O

3 (15 nm)/ZrO

2 (3 nm)] × 3 nanolaminate film is shown in

Figure 4a″. Clear spatial distributions of Al, Zr, O, Fe, and Cr were observed, confirming that the Al

2O

3 and ZrO

2 layers remained distinctly separated without the formation of interfacial compounds, which can be attributed to their high thermodynamic stability. These results indicate the successful formation of a stable nanolaminate structure. A similar uniform and well-defined nanolaminate structure was observed for the [Al

2O

3 (9 nm)/ZrO

2 (9 nm)] × 3 nanolaminate film, as shown in

Figure 4b–b″. From the enlarged view of the laminate film and the corresponding local structure analysis based on FFT patterns (

Figure 4b′), the [Al

2O

3 (9 nm)/ZrO

2 (9 nm)] × 3 nanolaminate film exhibited partially formed fringe patterns in certain local regions, suggesting the presence of limited nanocrystalline domains. The corresponding FFT image also shows a few spot patterns at the same lattice spacing, although these features were not detected in the XRD analysis (

Figure 3). Notably, the EDS mapping shown in

Figure 4b″ indicates the presence of surface defects on the stainless-steel substrate, such as Cr-rich precipitates. However, after deposition of the Al

2O

3/ZrO

2 nanolaminate film, these surface defects were completely passivated. This demonstrates that ALD-deposited nanolaminate coatings can grow uniformly even on substrates with surface irregularities, thereby forming a highly conformal and protective passivation layer.

Figure 4c–c″ presents the cross-sectional HRTEM image, along with the corresponding FFT patterns and EDS elemental mappings, of the [Al

2O

3 (3 nm)/ZrO

2 (15 nm)] × 3 nanolaminate film, in which alternating layers of approximately 3.3 nm Al

2O

3 and 15.4 nm ZrO

2 were clearly observed. The HRTEM and EDS mapping results also indicate that the Al

2O

3/ZrO

2 nanolaminate films were successfully deposited according to the designed layer architecture. However, in contrast to the films of [Al

2O

3 (15 nm)/ZrO

2 (3 nm)] × 3 and [Al

2O

3 (9 nm)/ZrO

2 (9 nm)] × 3 nanolaminate films, the 15 nm-thick ZrO

2 layer clearly exhibited multiple fringe patterns indicating a polycrystalline ZrO

2 microstructure. In the corresponding FFT image (

Figure 4c′), multiple diffraction spots associated with these spacings were distributed in continuous ring patterns, indicating the presence of numerous nanocrystallites with random orientations. These findings are consistent with the diffraction peaks observed in the XRD results of

Figure 3, confirming that thicker ZrO

2 layers tend to crystallize and evolve into polycrystalline structures. From these observations, it is evident that as the ZrO

2 layer thickness increases (>~9 nm), localized crystallization occurs within the film, leading to the development of polycrystalline structures. In contrast, the thinner ZrO

2 layer (~3 nm) maintains an amorphous structure, forming a dense and defect-free interface. A similar thickness-dependent crystallization behavior was observed in ALD-ZrO

2 using TEMAZr and O

3, where a transition from an amorphous to a crystalline phase occurred at a critical thickness of approximately 6–8 nm [

17]. These structural observations provide a basis for the subsequent electrochemical corrosion evaluation, in which the influence of crystallinity-dependent ionic diffusion pathways on the corrosion behavior of the nanolaminate films will be further examined.

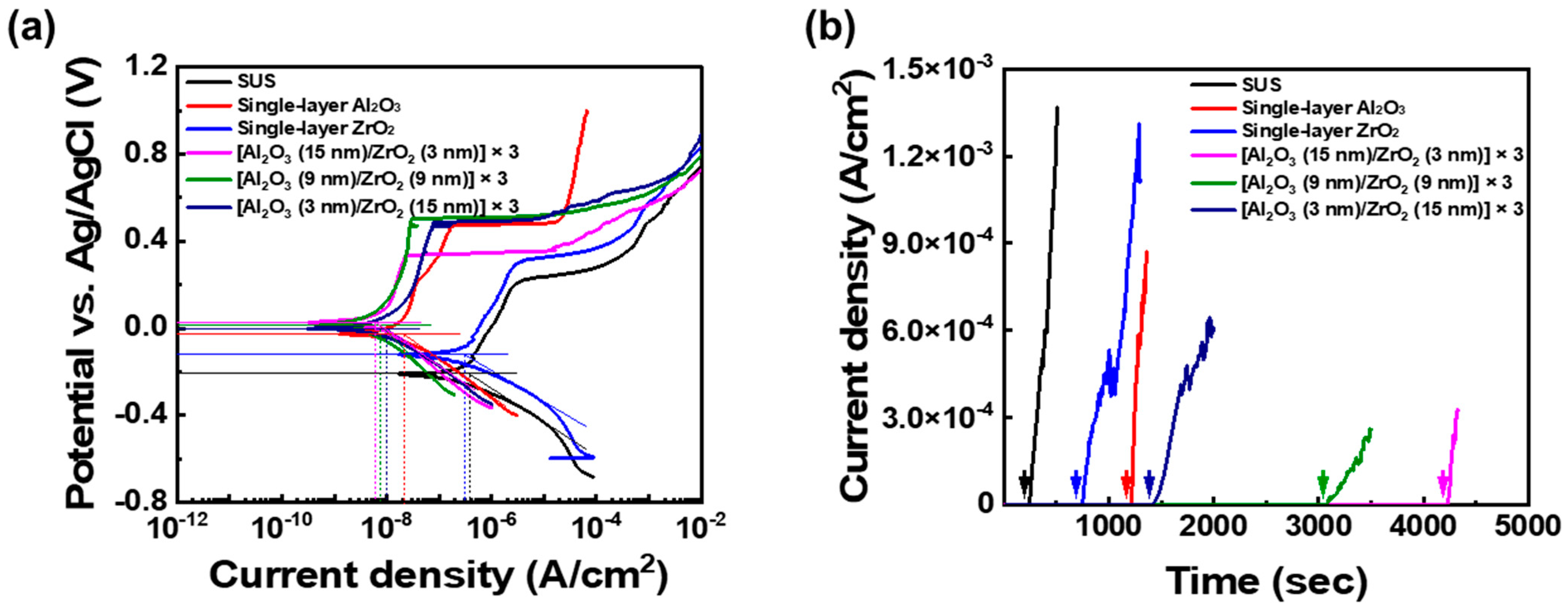

To evaluate the corrosion behavior of the ALD films, potentiodynamic and potentiostatic polarization tests were conducted on the prepared samples.

Figure 5a shows the potentiodynamic polarization test result of bare SUS304, single-layer Al

2O

3 and ZrO

2 coated, and three types of nanolaminate film-coated SUS304. The extracted electrochemical parameters

Ecorr,

Icorr, and protective efficiency (PE) were calculated using the Tafel equation and summarized in

Table 1. The protective efficiency was calculated using the following equation:

The results showed a general increase in Ecorr and decrease in Icorr for all coated samples compared to the bare SUS304 substrate. The bare stainless steel exhibited an Ecorr of −208.98 mV and an Icorr of 373.86 nA/cm2, whereas the coated samples showed more positive Ecorr values and significantly lower Icorr values. For instance, the single-layer Al2O3 and ZrO2 film-coated samples showed Ecorr values of −120.91 mV and −26.64 mV, and Icorr values of 21.14 nA/cm2 and 307.64 nA/cm2, respectively. The nanolaminate structures exhibited a greater reduction in Icorr than single-layer Al2O3 or ZrO2 films. Among the three types of nanolaminate film-coated samples, the [Al2O3 (15 nm)/ZrO2 (3 nm)] × 3 nanolaminate film exhibited the most positive Ecorr values (26.98 mV) and the lowest Icorr (6.20 nA/cm2), indicating the best corrosion resistance properties. This enhanced performance is attributed to the amorphous structure of both Al2O3 and ZrO2 layers, which effectively block the pathways of ion diffusion and delay corrosion initiation.

Next, potentiostatic polarization tests were conducted to investigate the long-term stability of the bare SUS304 substrate, single-layer Al

2O

3 and ZrO

2 film, and three types of Al

2O

3/ZrO

2 nanolaminate films.

Figure 5b shows the results of potentiostatic polarization tests conducted at a constant applied potential of 0.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl. This method evaluates the initiation of pitting corrosion by monitoring changes in current density over time under constant potential conditions. For the bare SUS304 sample, a rapid increase in current density was observed after approximately 200 s, indicating that pitting corrosion occurred at a very early stage. Similar behavior was observed for the single-layer ZrO

2 and Al

2O

3 coatings, though the onset of pitting varied depending on the film type. In particular, the single-layer ZrO

2 film exhibited pitting after about 700 s, which is attributed to the grain boundaries present in its polycrystalline structure acting as diffusion pathways for external ions, allowing rapid penetration and corrosion initiation. In contrast, the single-layer Al

2O

3 film exhibited pitting only after approximately 1200 s, as its dense amorphous structure effectively blocked ion diffusion. Meanwhile, all nanolaminate coatings maintained relatively stable current densities over an extended polarization period. The onset times of pitting corrosion were delayed to approximately 1400 s for the [Al

2O

3 (3 nm)/ZrO

2 (15 nm)] × 3, 3100 s for the [Al

2O

3 (9 nm)/ZrO

2 (9 nm)] × 3, and 4200 s for the [Al

2O

3 (15 nm)/ZrO

2 (3 nm)] × 3 nanolaminate films, respectively. This progressive delay can be interpreted as a consequence of microstructural evolution induced by changes in the crystallinity of the ZrO

2 layer with increasing thickness, which affects ion diffusion pathways and, consequently, the overall protective performance of the coating. After potentiostatic tests, the changes in the surface of the samples were observed as shown in

Figure 6. The uncoated SUS304 exhibited severe pitting corrosion, with pit diameters of up to ~50 µm (

Figure 6a). In contrast, the pit size of the coated samples varied depending on the film structure and composition. As shown in

Figure 6b,c, the single-layer film-coated samples effectively suppressed the progression of pitting corrosion, with pit diameters limited to around 10 µm. Furthermore, in the nanolaminate film-coated samples (

Figure 6d–f), only fine pits smaller than 1 µm were observed, indicating that both the initiation and progression rates of pitting corrosion were significantly inhibited.