Study on the Flow Behavior of Molten Pool in K-TIG Welding of Invar 36 and Stainless Steel Dissimilar Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Weld Surface Quality Analysis

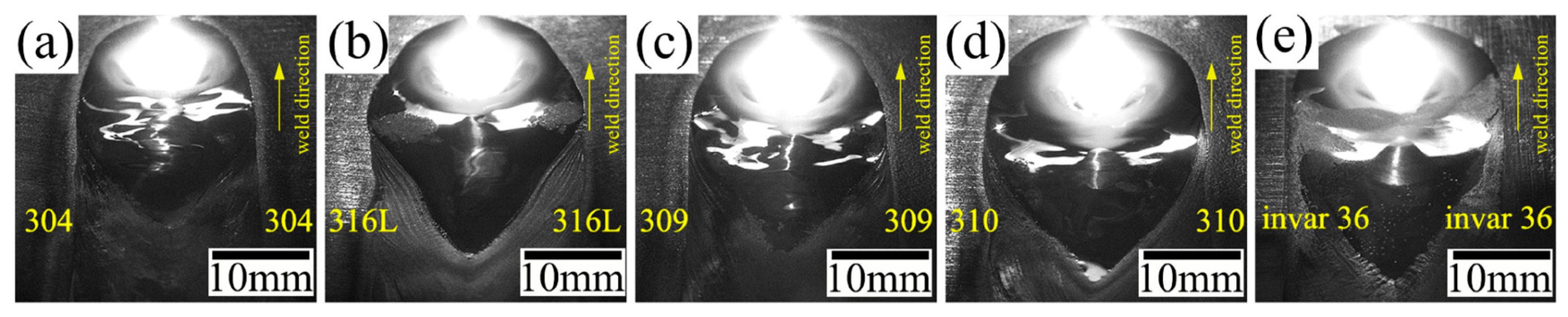

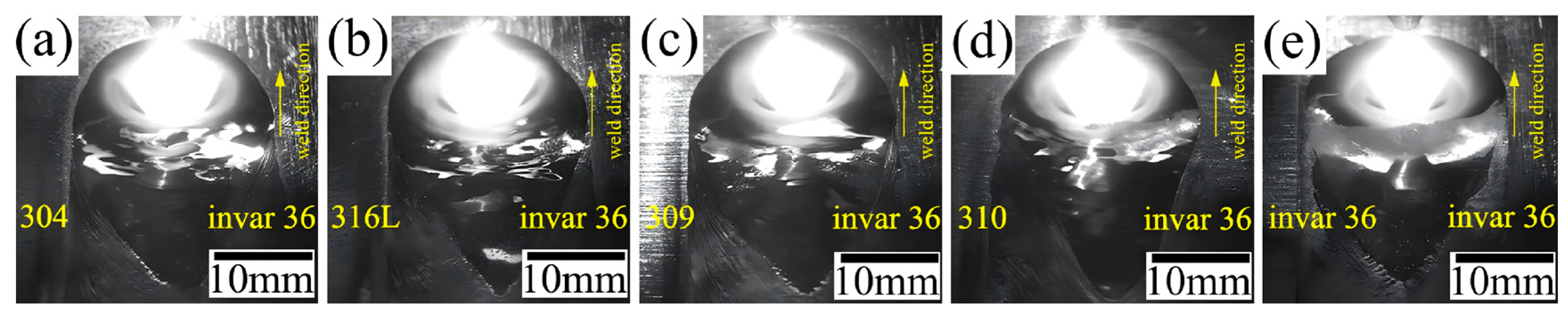

3.2. Observation and Analysis of Molten Pool and Arc in Welding Process

3.3. Metallographic Analysis of Weld Cross-Section

4. Discussion

4.1. Welding Arc Deflection Mechanism of Invar 36 and Stainless Steel Dissimilar Materials

4.2. Analysis of Weld Pool Flow Behavior

4.2.1. Analysis of Molten Metal Flow Behavior on the Surface of Molten Pool

4.2.2. Analysis of Molten Metal Flow Behavior in Molten Pool

5. Conclusions

- [1]

- In the welding process of the same material of stainless steel, the welding arc shape presented a typical bell-like shape, demonstrating good symmetry. When Invar 36 was welded with the same material, the welding arc shape also shows a typical bell shape, but there is obvious shrinkage. In the welding of Invar 36 and stainless steel dissimilar materials, the arc was influenced by the ferromagnetism of Invar 36, leading to arc deflection.

- [2]

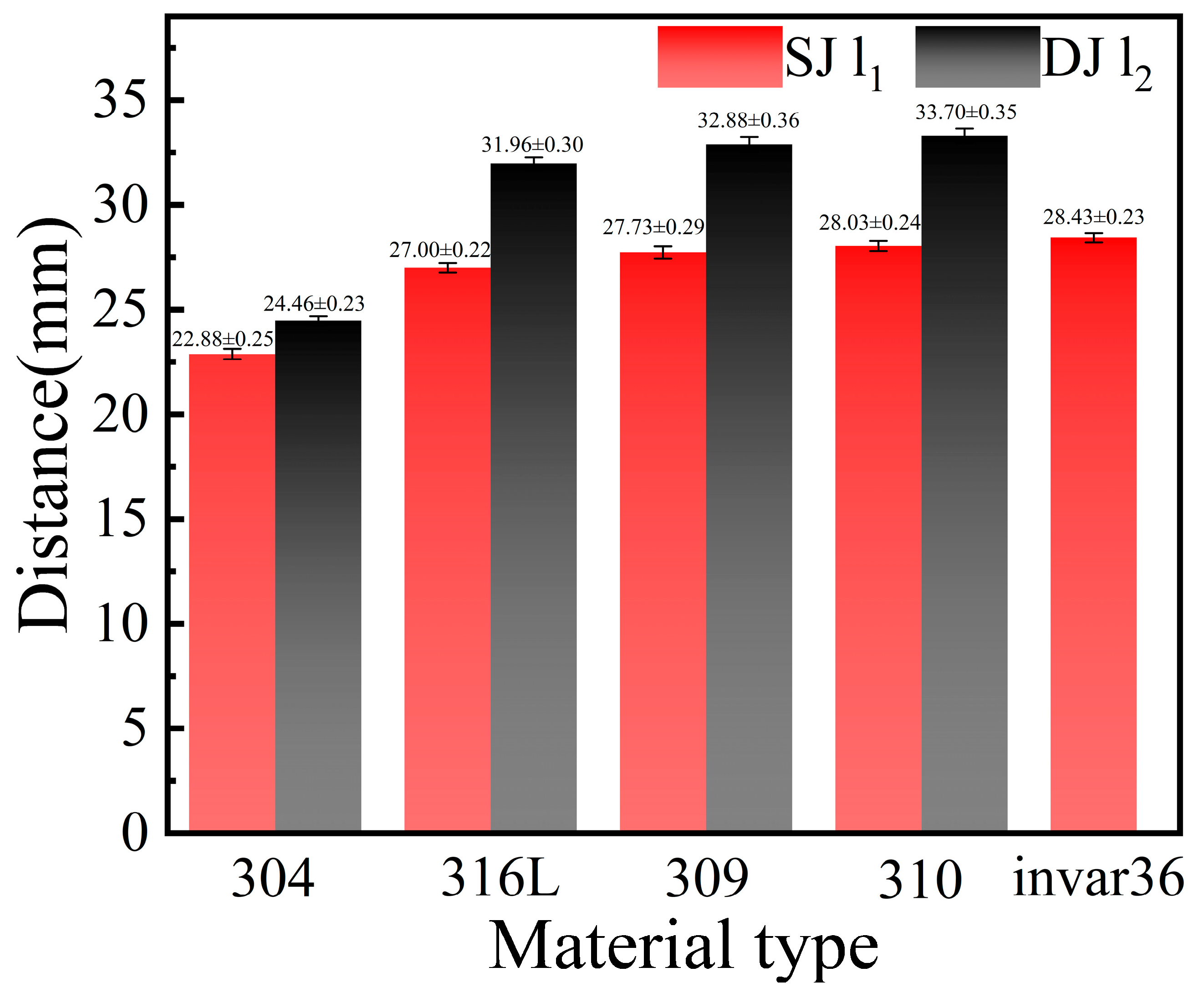

- When the viscosity of the liquid metal increased and the thermal conductivity decreased, the distance l from the tip of the crater tail to the end of the weld increased significantly. When the same material was welded, l1 increased from 22.88 mm to 28.43 mm, with a maximum difference of 24%, while the l2 of dissimilar welds between stainless steel and Invar 36 increased from 24.26 mm to 33.70 mm, with a maximum difference of 37%.

- [3]

- In the same metal welding of stainless steel, the microstructure of the cross-section of the joint was distributed symmetrically, and the HAZ was relatively narrow. However, in the dissimilar metal welding of Invar 36 alloy and stainless steel, a significant HAZ was observed on the Invar 36 side. As the thermal conductivity of stainless steel decreased, the width of the HAZ increased from 1.77 mm to 2.03 mm.

- [4]

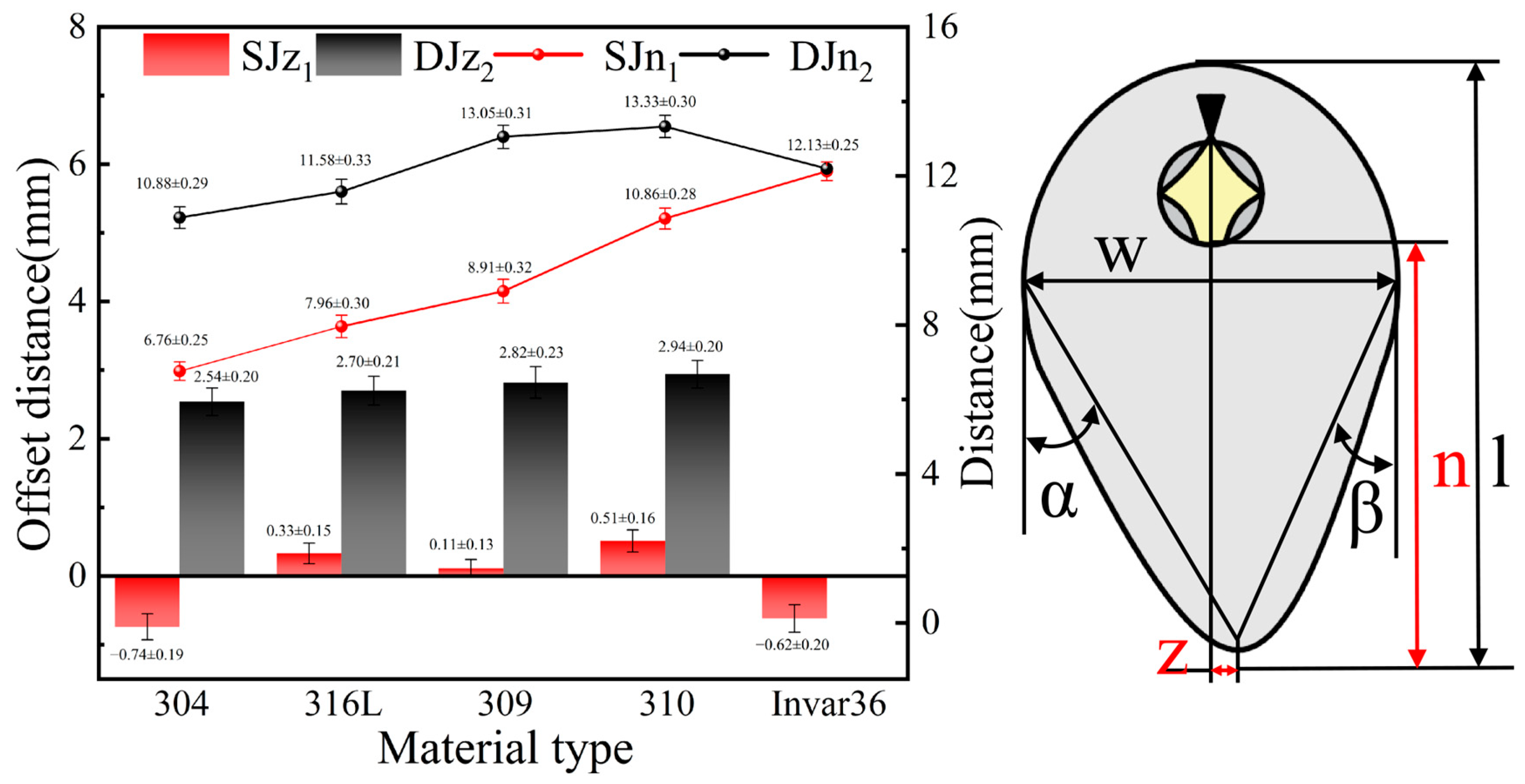

- During the welding process of dissimilar materials, the flow of molten metal on the surface of the molten pool was mainly affected by the physical properties of the material. The offset z of the tip of the molten pool to the center line increased from 2.54 mm to 2.94 mm. The molten metal in the molten pool was affected by many factors such as viscosity, thermal conductivity and uneven energy deposition, resulting in the accumulation of metal on the Invar36 side.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Q.; Wei, K.; Yang, X. Microstructures and unique low thermal expansion of Invar 36 alloy fabricated by selective laser melting. Mater. Charact. 2020, 166, 110409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Yang, Q.; Ling, B. Mechanical properties of Invar 36 alloy additively manufactured by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 772, 138799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgul, B.; Mehmet, K.; Erden, F. The puzzling thermal expansion behavior of invar alloys: A review on process-structure-property relationship. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2024, 49, 254–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. Effect of Weld Metal on the Susceptibility of Austenitic Stainless Steel to Ductility-dip Cracking. Welded Pipe Tube 2023, 46, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neissi, R.; Shamanian, M.; Hajihashemi, M. The Effect of Constant and Pulsed Current Gas Tungsten Arc Welding on Joint Properties of 2205 Duplex Stainless Steel to 316L Austenitic Stainless Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2016, 25, 2017–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A.; Huang, L.; Fan, A. Application of Intelligent Pipeline Technology in the Field of Long-Distance Pipelines Corrosion Prevention. Welded Pipe Tube 2023, 46, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Gao, Q.; Gu, C. The porosity formation mechanism in the laser-MIG hybrid welded joint of Invar alloy. Opt. Laser Technol. 2017, 95, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathabai, S.; Jarvis, B.L.; Barton, K.J. Comparison of keyhole and conventional gas tungsten arc welds in commercially pure titanium. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 299, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, B.L.; Ahmed, N.U. Development of keyhole mode gas tungsten arc welding process. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2000, 5, 21–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, C.; Liu, Y. Keyhole Behaviors Influence Weld Defects in Plasma Arc Welding Process. Weld. J. 2015, 94, 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Van Nguyen, A.; Tashiro, S. Elucidation of the weld pool convection and keyhole formation mechanism in the keyhole plasma arc welding. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 131, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Dai, P.; Ma, R. Mechanism study of flow characteristics of molten pool and keyhole dynamic behavior of K-TIG welding. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 130, 1279–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q. Numerical simulation of flow field in the Invar alloy laser-MIG hybrid welding pool based on different heat source models. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2018, 28, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, P.; Liu, H. Numerical simulation of molten pool formation during laser transmission welding between PET and SUS304. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 131, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Numerical analysis of the behavior of molten pool and the suppression mechanism of undercut defect in TIG-MIG hybrid welding. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 218, 124757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Tashiro, S. Study of molten pool dynamics in keyhole TIG welding by numerical modelling. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 119, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Terasaki, H.; Ushio, M. A unified numerical modeling of stationary tungsten-inert-gas welding process. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2002, 33, 2043–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggirala, A.; Kalvettukaran, P.; Acherjee, B. Numerical simulation of the temperature field, weld profile, and weld pool dynamics in laser welding of aluminium alloy. Optik 2021, 247, 167990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.G.; Tsai, H.L.; Na, S.J. Heat transfer and fluid flow in a partially or fully penetrated weld pool in gas tungsten arc welding. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2001, 44, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Dong, B.; Cai, X. Numerical simulation on molten pool behavior of narrow gap gas tungsten arc welding. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 4861–4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Xiao, Z.; Ramesh, A. On the melt pool flow and interface shape of dissimilar alloys via selective laser melting. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 145, 106833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, W.; Chen, Y. An experimental and numerical study on the evolution of pores and its effect on the tensile properties of LPBF Invar36 with different energy density. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 3064–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Murakawa, H. Numerical simulation of temperature field and residual stress in multi-pass welds in stainless steel pipe and comparison with experimental measurements. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2006, 37, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltyukov, A.; Ladyanov, V.; Sterkhova, I. Effect of small nickel additions on viscosity of liquid aluminum. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 296, 111764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitava, D.; Tarasankar, D. A smart model to estimate effective thermal conductivity and viscosity in the weld pool. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 95, 5230–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, V.K.; Ghosh, P.K.; Saini, J.S. Analytical studies on thermal behaviour and geometry of weld pool in pulsed current gas metal arc welding. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 1318–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, H.M.; Tayebi, M. Comparative study of AISI 304L to AISI 316L stainless steels joints by TIG and Nd:YAG laser welding. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 767, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, H. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Invar36 alloy joints using keyhole TIG welding. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2020, 25, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, T. Investigation of temperature-dependent magnetic properties and coefficient of thermal expansion in invar alloys. Materials 2022, 15, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.P.; Souza, D.; Scotti, A. Models to describe plasma jet, arc trajectory and arc blow formation in arc welding. Weld. World 2011, 55, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananya, S.; Ayusa, A.B.; Parida, S.K. Electronic, magnetic and thermal behavior near the Invar compositions of Fe-Ni alloys. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2025, 280, 147540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S.; Wang, Y. Computer simulation of convection in moving arc weld pools. Metall. Trans. A 1986, 17, 2271–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhang, L.; Jahanshahi, S. From viscosity and surface tension to marangoni flow in melts. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2003, 34, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Chung, F. Unsteady marangoni flow in a molten pool when welding dissimilar metals. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2000, 31, 1387–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Co | Mo | Ni | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304 | 0.041 | 0.037 | 0.76 | 0.024 | 0.003 | 18.03 | - | - | 8.03 | Bal. |

| 316 | 0.003 | 0.36 | 1.14 | 0.035 | 0.006 | 16.26 | - | 2.11 | 10.31 | Bal. |

| 309 | 0.064 | 0.58 | 1.12 | 0.022 | 0.024 | 22.12 | - | - | 12.06 | Bal. |

| 310 | 0.062 | 0.68 | 1.04 | 0.025 | 0.022 | 24.15 | - | - | 19.25 | Bal. |

| Invar 36 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | - | 36 | Bal. |

| Materials | Thermal Conductivity/W·m−1·K−1 | Thermal Expansion Coefficient/ K−1 | Specific Heat Capacity/J·Kg−1·K−1 | Surface Tension/N·m−1 | Viscosity/Pa·s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304 | 14.6 | 17.3 × 10−6 | 452 | 1.44 | 0.004 |

| 316 | 12.41 | 17.6 × 10−6 | 462 | 1.25 | 0.005 |

| 309 | 11 | 14.9 × 10−6 | 502 | 1.22 | 0.007 |

| 310 | 10.8 | 14.4 × 10−6 | 502 | 1.17 | 0.009 |

| Invar 36 | 6.2 | 1.2 × 10−6 | 801 | 1.93 | 0.01 |

| Materials | Welding Speed/(mm/min) | Welding Current/A | Voltage/V | Arc Length (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304-304 | 260 | 450 | 18 | 2 |

| 316-316 | 260 | 450 | 18 | 2 |

| 309-309 | 260 | 450 | 18 | 2 |

| 310-310 | 260 | 450 | 18 | 2 |

| Invar 36-Invar 36 | 260 | 450 | 18 | 2 |

| Invar 36-304 | 260 | 450 | 18 | 2 |

| Invar 36-316L | 260 | 450 | 18 | 2 |

| Invar 36-309 | 260 | 450 | 18 | 2 |

| Invar 36-310 | 260 | 450 | 18 | 2 |

| Material | Left Angle of the SJ (°) | Right Angle of the SJ (°) | Material | Left Angle of the DJ (°) | Right Angle of the DJ (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304-304 | 38.0 | 34.7 | 304-Invar 36 | 37.0 | 26.0 |

| 316-316 | 36.2 | 37.4 | 316-Invar 36 | 34.1 | 27.4 |

| 309-309 | 36.1 | 39 | 309-Invar 36 | 33.2 | 25.8 |

| 310-310 | 36.4 | 38.2 | 310-Invar 36 | 29.9 | 23.5 |

| Invar 36-Invar 36 | 30.2 | 31.9 | Invar 36-Invar 36 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, C.; Xu, P.; Du, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, F.; He, B.; Xuan, Y. Study on the Flow Behavior of Molten Pool in K-TIG Welding of Invar 36 and Stainless Steel Dissimilar Materials. Coatings 2026, 16, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010058

Li C, Xu P, Du Y, Li J, Liu H, Wang F, He B, Xuan Y. Study on the Flow Behavior of Molten Pool in K-TIG Welding of Invar 36 and Stainless Steel Dissimilar Materials. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Chunsi, Peng Xu, Yonggang Du, Jiayuan Li, Hongbing Liu, Fei Wang, Bowei He, and Yang Xuan. 2026. "Study on the Flow Behavior of Molten Pool in K-TIG Welding of Invar 36 and Stainless Steel Dissimilar Materials" Coatings 16, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010058

APA StyleLi, C., Xu, P., Du, Y., Li, J., Liu, H., Wang, F., He, B., & Xuan, Y. (2026). Study on the Flow Behavior of Molten Pool in K-TIG Welding of Invar 36 and Stainless Steel Dissimilar Materials. Coatings, 16(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010058