1. Introduction

Rammed earth structures are outstanding examples of human adaptation to nature and use of local materials. They represent an indispensable component of global cultural heritage. These structures carry profound historical information and construction wisdom. They also embody principles of sustainable development that remain highly relevant today. However, the long-term preservation of these earthen heritage sites faces severe challenges. This is particularly true in humid and rainy climates [

1,

2].

Among various deterioration factors, water is the most active and critical agent driving the degradation of rammed earth materials and structures [

3,

4]. High humidity environments not only cause direct material softening and strength loss but also trigger complex physical, chemical, and biological processes. These processes include the migration and crystallization of soluble salts, stress from wet-dry cycles, and the promotion of microbial and plant growth. Together, they accelerate wall weathering. Water-induced surface pathologies are diverse in type, interconnected in mechanism, and complex in spatial distribution. They form a nonlinear degradation system. This complexity presents significant difficulties in accurately diagnosing deterioration causes and developing effective conservation interventions [

5,

6].

Macao has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Its cultural heritage system is rich and diverse. Among this, fortification structures serve as a unique testimony to Sino-Portuguese cultural convergence. They possess outstanding historical and technological value. Macao is located on the coast of the South China Sea. It features a typical maritime subtropical climate. The region experiences year-round high temperatures, high humidity, and abundant rainfall. This creates a highly representative hot-humid environment [

7,

8,

9]. This specific geographical location and climatic condition pose a particular challenge. The rammed earth heritage in Macao faces more severe coupled water-thermal effects compared to other regions [

10,

11]. Therefore, researching the conservation status and deterioration mechanisms of these sites is crucial. It provides an important reference for the protection of earthen ruins located in similar climatic zones.

The investigation and documentation of traditional rammed earth heritage primarily rely on on-site surveys and manual mapping. These methods present limitations in long-term research and conservation practice [

12]. Worldwide, research on rammed earth architectural heritage has been extensively conducted across diverse climatic and geological conditions. For instance, Macchioni et al. (2024) implemented seismic retrofitting and systematic long-term monitoring of the earthen heritage at the Church of Kuñotambo in Peru by integrating traditional techniques with a structural health monitoring system, which offers a scalable collaborative framework for the preventive conservation of earthen sites in high seismic risk areas [

13]. A significant geographical imbalance exists within current research in China. Scholarly outputs are heavily concentrated in the arid and semi-arid regions of Northwest China. Mechanisms of deterioration such as salt crystallization and wind erosion in these areas have been relatively well elucidated [

14,

15,

16]. For example, Wang et al. (2025) [

17] integrated low-altitude UAV photogrammetry with explainable machine learning. Their work first revealed the spatial clustering characteristics of erosion on the rammed earth walls of the Ming Great Wall in Gansu. They identified soil salinization, topographic relief, and annual precipitation as key driving factors. Zhang et al. (2022, 2023) [

18,

19] employed terrestrial laser scanning and the Random Forest algorithm, respectively. Their studies quantitatively characterized the isotropic morphological features of rammed earth layers and the influence of standardized construction techniques on the Northwestern Ming Great Wall. In contrast, research on rammed earth heritage in the hot-humid maritime climate of Southern China, such as in Macao, remains extremely scarce. Although Zhai et al. (2025) [

20] systematically analyzed the material composition of traditional rammed earth dwellings in Macao, their research revealed how optimized particle gradation, lime addition, and artificial aggregates enhanced structural stability and environmental adaptation. However, processes like moisture movement and bioerosion in hot-humid environments are fundamentally different from those in the arid Northwest. This fundamental difference makes it difficult to directly apply existing research findings from arid regions. Consequently, there is an urgent need for systematic research on rammed earth heritage in hot-humid regions. This research is essential to fill critical knowledge gaps in the field [

21,

22].

In recent years, non-destructive testing techniques have played an increasingly critical role in cultural heritage diagnostics. Among them, Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) rapidly acquires massive 3D point cloud data from heritage surfaces. This enables the construction of high-precision geometric models. TLS not only achieves permanent digital archiving of heritage morphology but also supports the precise quantification of surface pathologies and deformation analysis. This capability has advanced documentation practices from qualitative description towards quantitative diagnosis [

23,

24,

25]. Messaoudi et al. (2018) [

26] integrated image-based 3D reconstruction with domain ontology technology—a framework for organizing and representing knowledge within a specific field. They achieved spatial semantic annotation of the conservation state of architectural heritage, which involves attaching meaningful labels or descriptions to specific locations or features within the 3D model. This work established a multidimensional correlation analysis framework. It provided a digital methodology combining semantic and morphological features for heritage conservation decision-making. Liu and Bin Mamat (2024) [

27] applied TLS to create a high-precision point cloud model (a dense set of 3D data points accurately representing the surface geometry) of the Dacheng Hall. Their accuracy assessment verified the reliability of TLS for measuring complex architectural components. This provides an accurate and reliable data foundation for the conservation and restoration of heritage buildings.

Concurrently, thermal imaging technology captures infrared radiation from object surfaces. It can visually reveal internal defects and moisture distribution anomalies invisible to the naked eye. In rammed earth conservation, this technology has been successfully used to identify internal water infiltration areas in walls. It also detects voids and assesses the uniformity of protective materials. Thermal imaging provides direct physical field evidence for understanding moisture-related deterioration mechanisms [

28,

29,

30]. Alexakis et al. (2024) [

31] combined infrared thermography to achieve high-accuracy identification of rising damp in historic masonry. Their work offers an efficient, non-invasive method for detecting moisture damage in cultural heritage.

Previous research on earthen heritage has often treated surface morphology and water-salt transport as separate subjects, failing to adequately explain how the three-dimensional geometry of a wall governs moisture pathways and subsequently leads to different types of surface deterioration. In particular, there remains limited understanding of how micro-environmental factors—such as those arising from construction techniques or wall orientation—influence the spatial distribution of moisture and salts. A systematic explanation is still lacking to clarify the complete sequence from geometric form to moisture movement and, finally, to pathology development, especially under the combined effects of wet-dry cycles, temperature fluctuations, and salt activity [

32,

33,

34].

Based on the aforementioned research background and existing challenges, the core objective of this study is to clarify the causal relationships between the geometric morphology, moisture transport pathways, and differentiated pathology patterns of the Old Wall in Macao. This aims to provide a theoretical basis for the precise conservation of this rammed earth heritage.

To achieve this goal, this study proposes and implements a comprehensive diagnostic methodology. This method innovatively integrates TLS, infrared thermography, and detailed field investigation. Through the fusion analysis of multi-source data, it aims to construct a coupled model. This model can fully explain the interactive processes of “geometry-hydrology-pathology”. The model not only seeks to describe the manifestations of pathologies but also strives to reveal the hidden hydrological and mechanical processes driving their spatial differentiation.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 details the data acquisition scheme and processing procedures. This includes the TLS scanning strategy, thermal imaging acquisition, and the surface analysis workflow.

Section 3 presents the Results and Discussion. It sequentially presents and analyzes the geometric anomalies of the wall and the spatial distribution characteristics of surface pathologies. Finally, it integrates all evidence to demonstrate the proposed comprehensive mechanistic model.

Section 4 summarizes the main conclusions of this study. It also discusses the implications for heritage conservation practice and suggests future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study focuses on a section of rammed earth defensive wall (designated MM033) [

35] located on the Macao Peninsula. It is situated less than 50 m from the Ruins of St. Paul’s and the Na Tcha Temple (

Figure 1). This wall segment was a key component of the defensive system constructed by the Portuguese in Macao. Its construction history dates back to 1569. A notable historical feature is that it was repeatedly built and subsequently demolished due to opposition from Chinese authorities. In 1632, the Portuguese rebuilt this wall section, citing the need to defend against Dutch invasion. Following this reconstruction, walls were erected along the northern, eastern, and southern sides of Macao. These were complemented by various fortresses and artillery batteries, forming a complete defensive system. Only the western inner harbor remained without a wall [

36].

The selected wall section (MM033) is considered representative of the Macao rammed earth heritage for several reasons. First, it is an integral part of the historically complete defensive system, sharing the same construction era, strategic purpose, and documented historical pressures (e.g., repeated rebuilding) as other sections [

36]. Second, it exhibits the classic and sophisticated “stone foundation, rammed earth body, sloping roof” construction technique that was characteristic of Portuguese military architecture in Macao and adapted to the local humid climate [

20]. Finally, its current exposure to the urban environment (proximity to roads and buildings) and the clear spatial variation in deterioration states (leading to our division into Sections A, B, and C) make it an ideal “living laboratory” to study the differentiated deterioration mechanisms under a single climatic regime but varied micro-environmental conditions.

The wall demonstrates sophisticated construction techniques adapted to the local environment. It follows the classic construction model of “stone foundation, rammed earth wall body, and sloping roof”. The rubble masonry foundation effectively blocks groundwater capillary rise and aids drainage. The thick rammed earth wall serves as the main structural layer. It was constructed using a mixture of sand, silt, fine gravel, rice straw, and oyster shell lime. This mixture was built up through layered ramming. Each loose layer of material, approximately 5–10 cm thick, was compacted by ramming to about one-third of its original thickness. This process achieved very high compactness. The brick-and-tile sloping roof at the top acts like a crown. It prevents direct rainwater erosion of the wall top. This feature reflects excellent adaptation to Macao’s rainy climate [

20,

35,

36].

Based on clearly observed differences in deterioration characteristics during field survey, and considering the wall’s inherent structural and construction separations, the study wall was systematically divided into three sections: A–C. This division enables comparative analysis. The specific criteria for zoning are as follows. Section A and Section B are separated by a vertical, continuous blue-brick masonry partition. This structural separation forms a clear physical boundary between the two sections. The boundary between Section B and Section C is defined by the wall’s original city gate. This historical structural element creates a natural interruption in the wall material, resulting in a distinct structural discontinuity. This zoning scheme not only reflects the objective physical separation within the wall’s construction but also aims to utilize these three adjacent sections. These sections differ in construction and micro-environment. The scheme establishes a clear anatomical unit and analytical framework for subsequent comparative study of spatial pathology differentiation patterns and their driving mechanisms (

Figure 2).

2.2. Data Collection

To achieve the stated research objective, an integrated diagnostic approach was employed, combining Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), Infrared Thermography (IRT), and detailed field investigation. Each technique served a distinct purpose: TLS was used to acquire high-resolution 3D point clouds of the wall surface, enabling the precise quantification of geometric parameters (e.g., slope, flatness, verticality) and the spatial mapping of surface pathologies. IRT detected subtle temperature variations linked to evaporative cooling and thermal inertia, thereby inferring subsurface moisture distribution and identifying infiltration zones. Field investigation provided essential ground-truth data for validating remote-sensing outputs and for the accurate semantic classification of deterioration features. Together, these methods supplied complementary evidence for establishing the proposed “geometry–hydrology–pathology” coupling mechanism.

Data acquisition was performed using a Leica RTC360 terrestrial laser scanner (Leica Geosystems, Heerbrugg, Switzerland). Scans were conducted in the highest accuracy mode. Each scan station required a duration of 4 min and 20 s. In this mode, the nominal single-point accuracy is better than 1 mm. The scanning focused exclusively on the street-facing facade of the wall. The rear side of the wall was physically connected to adjacent residential buildings. This connection prevented the necessary operational space for scanning. Consequently, the rear side was excluded from the data acquisition.

A combination of distant and close-range scan setups was employed. This strategy overcame obstruction from vegetation at the wall base and ensured complete coverage of the facade. A total of six scan stations were established. Three stations were positioned approximately 5 m from the wall to capture its overall geometric profile. The other three stations were placed immediately adjacent to the wall (distance < 1 m) to record surface micro-features (

Figure 3).

Point cloud registration was completed in Cyclone Register 360 software through automatic recognition of spherical targets between scan stations. The registered point cloud then underwent boundary trimming and noise removal, producing a high-quality 3D model for subsequent analysis.

The thermal imaging data were obtained utilizing a FLIR e5 infrared thermal camera (manufactured by FLIR Systems, Inc., Wilsonville, OR, USA). The instrument features a thermal sensitivity of 0.1 °C and a native image resolution of 120 × 160 pixels. To ensure the detection of thermal anomalies caused by internal moisture, data were acquired over three consecutive days (1–3 October 2025) during pre-dawn hours (05:00–06:30) under clear, windless conditions. The ambient temperature recorded during these sessions ranged from 24 °C to 26 °C. The final thermal analysis used an average of the three daily datasets to minimize transient environmental effects and to highlight consistent moisture-related thermal patterns.

To ensure data quality and meet the specific requirements of different instruments, this study employed a time-segmented strategy for data acquisition. TLS surveys were conducted during dry, overcast days without rainfall. This scheduling avoided shadow interference and data distortion caused by direct sunlight. It also ensured the completeness and high accuracy of the point cloud data. Thermal imaging data collection was strictly scheduled for clear, windless periods before sunrise. This timing aimed to minimize interference from solar radiation on the wall’s surface temperature. Consequently, thermal anomalies caused by internal moisture distribution variations were highlighted. This approach ensured the effectiveness of the data for diagnosing water infiltration areas.

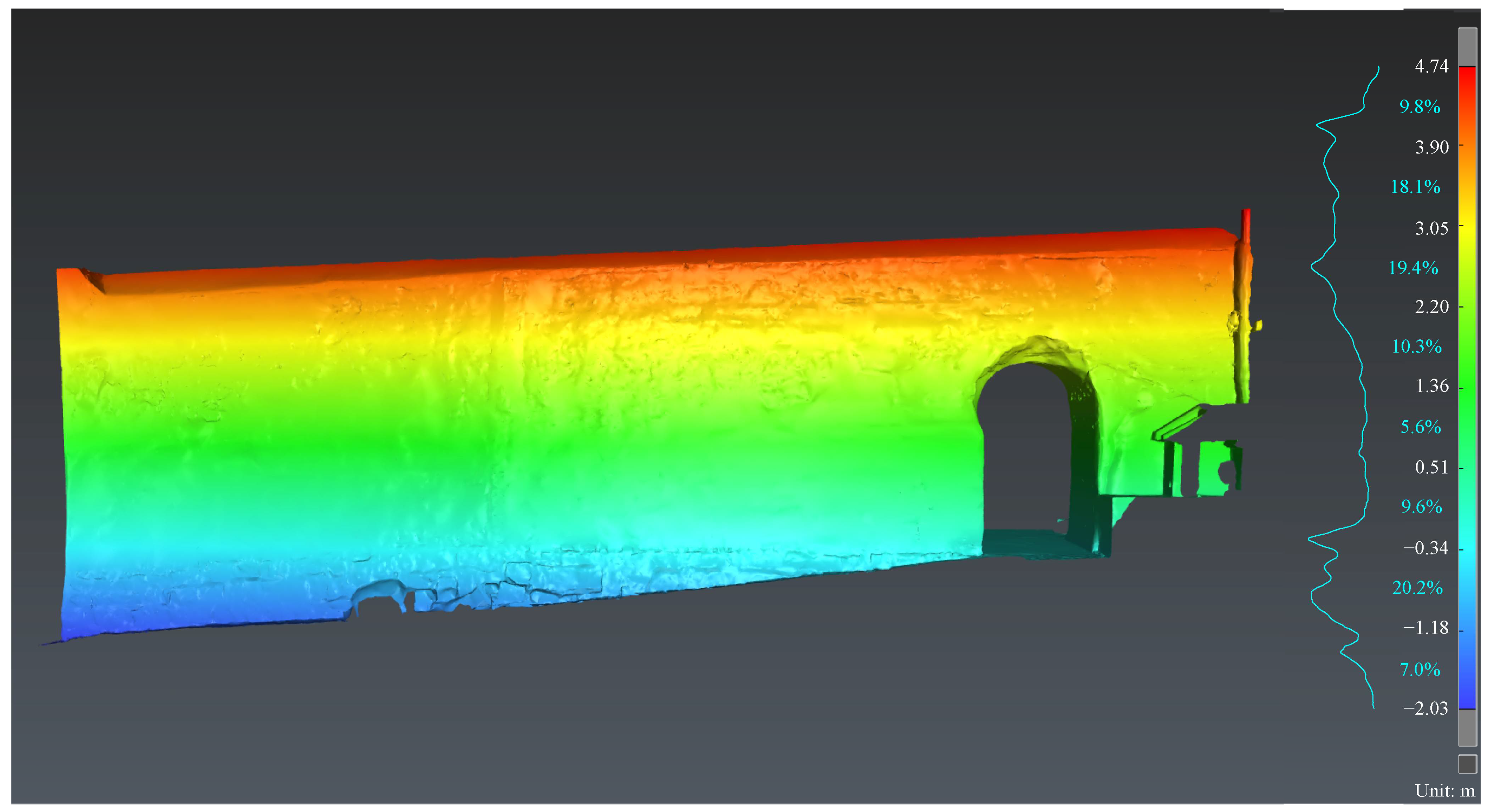

The raw point cloud data from all scan stations were processed using Leica Cyclone Register 360 software. The processing workflow included: (1) registration through automatic recognition of spherical targets to merge individual scans into a unified coordinate system; (2) stitching to create a complete 3D model of the wall facade; and (3) denoising, which involved boundary trimming and removal of discrete noise points to enhance model quality for subsequent analysis. A high-resolution three-dimensional point cloud archive of the rammed earth wall facade was successfully obtained through TLS, as visualized in

Figure 4. The registered dataset provides complete coverage of the study area. This high-quality digital record forms the essential geometric basis for all subsequent quantitative analyses presented in this study.

2.3. Surface Analysis Workflow

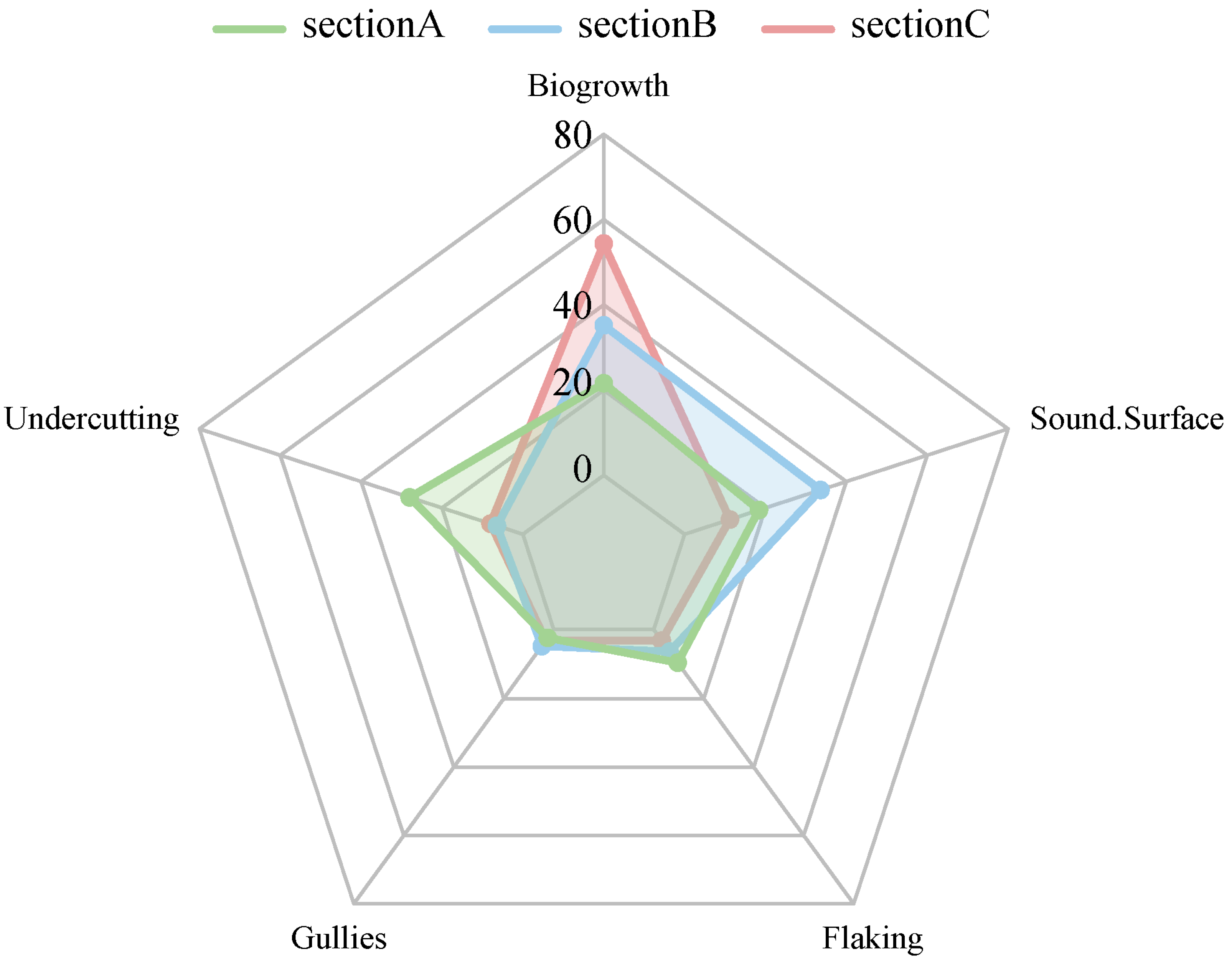

Surface analysis was conducted within the Cyclone 3DR environment. The mesh model was first aligned with an absolute coordinate system. Subsequently, a systematic analysis was performed. The wall top slope was calculated based on the mesh model. The wall top was divided into three characteristic sections (A, B, and C) for comparison. The surface flatness of the wall was quantitatively analyzed. Structural deformation areas were identified. Surface pathologies, including flaking, cracks, scour gully, undercutting, and biological colonization, were semantically segmented and mapped. This process integrated the point cloud’s reflectance intensity and geometric features.

To quantify the area of different surface pathologies (laking, cracks, scour gully, undercutting, and biological colonization), we performed manual semantic segmentation on the 3D model in Leica Cyclone 3DR (Leica Geosystems AG, Heerbrugg, Switzerland). The registered point cloud was first converted into a high-resolution triangular mesh, creating a continuous surface. An experienced conservator then manually outlined and labelled each pathology type on this 3D mesh. This process integrated visual characteristics from field photographs, point cloud reflectance, and geometric features. Finally, the software calculated the surface area of each labelled segment. The area proportion for a specific pathology in a wall section was derived as the ratio of its segmented area to the total area of that section.

The analysis of thermal imaging data aimed to convert surface temperature distribution into a qualitative indicator of internal moisture conditions within the wall. This served to further verify the conclusions derived from the point cloud data. Finally, spatial correlation analysis was performed by integrating the geometrically quantified parameters (slope, flatness), the digital pathology map, and the thermal moisture distribution map. This multi-source data fusion workflow established the methodological foundation for subsequently diagnosing hydrological pathways (infiltration vs. runoff) and revealing the coupled “geometry-hydrology-pathology” mechanism (

Figure 5).

2.4. Point Cloud Registration Quality Metrics

The quality of the point cloud registration, which directly affects the reliability of all geometric analyses, was evaluated using standard metrics from Cyclone Register 360 software. Registration Strength indicates the algorithmic confidence in alignment. Overlap quantifies the shared area between scans, with high overlap ensuring model completeness. Mean Absolute Error (MAE) measures the average alignment error in millimeters, directly reflecting precision. The Number of Connections defines the network topology. Together, these metrics verify that the final 3D model provides a high-fidelity and accurate digital representation of the wall.

4. Discussion

4.1. Geometric Anomalies and Sedimentation Inference

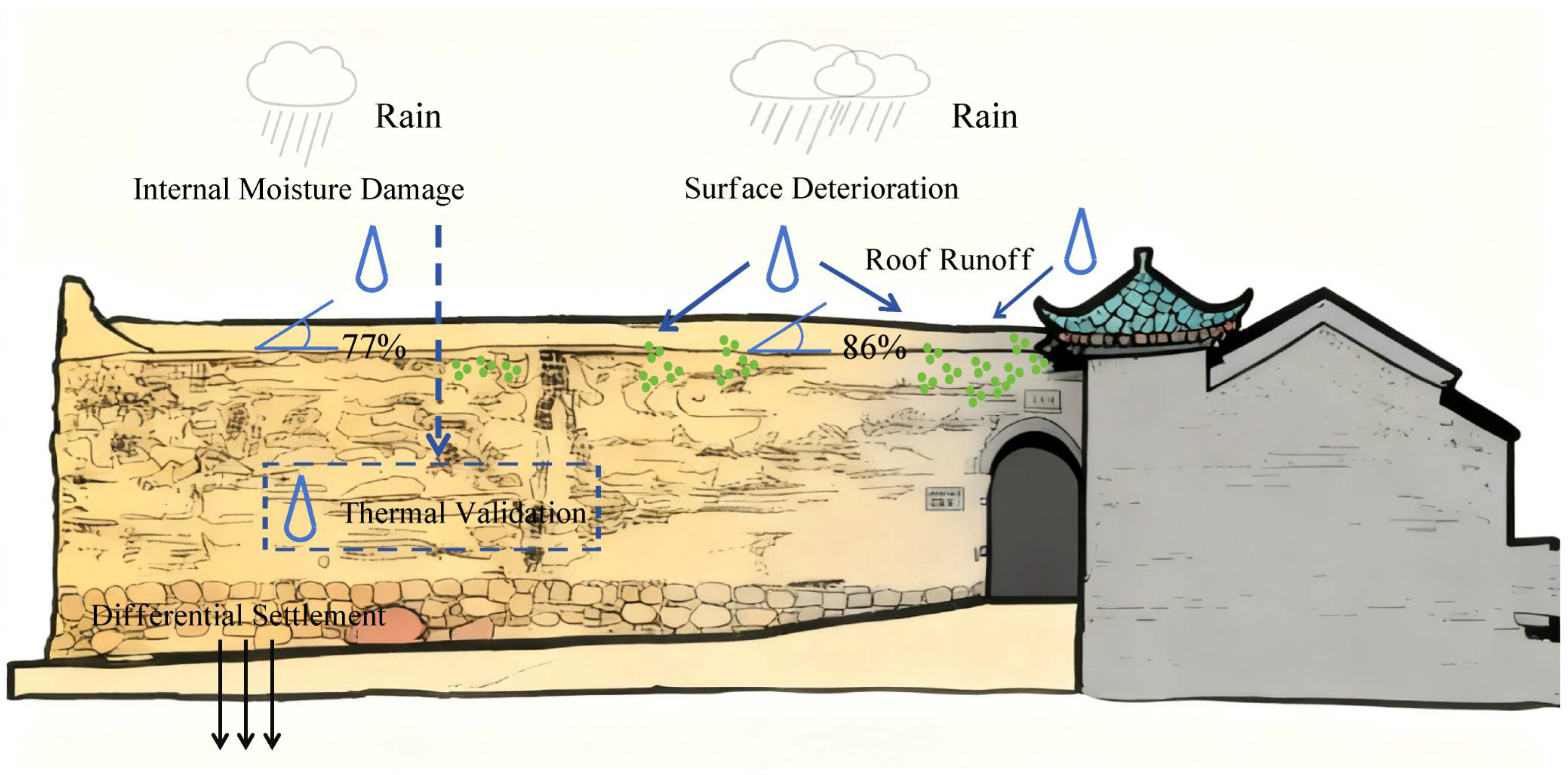

The systematic anomaly in wall top slope (77% in Section A vs. 86% in Sections B & C) strongly contradicts the reasonable expectation that the slope should be essentially consistent under unified design and construction. This systematic discrepancy strongly suggests that differential deformation likely occurred in the foundation of certain sections after the wall was built.

The systematic slope anomaly and the significant deterioration in wall facade flatness together form two independent geometric pieces of evidence. These support a strong inference: differential ground settlement likely occurred beneath Section A. This settlement process provides a comprehensive explanation for all the observed geometric anomalies. It would have caused Section A to sink overall or rotate relative to the other sections. Consequently, its top slope became gentler. This process also induced complex internal stress redistribution within the wall. This stress redistribution ultimately manifested as severe surface undulations (

Figure 7). The quantified geometric data collectively point to differential settlement under Section A as the root cause of its current structural geometric anomalies.

As shown in

Figure 12 in the Results section, the wall exhibits a systematic tilt downward along the slope in Section A. This verticality anomaly, combined with the significantly gentler wall top slope (

Figure 6) and severely deteriorated surface flatness (

Figure 7) in Section A, forms a complete chain of geometric evidence. These evidences collectively indicate that the foundation of Section A, located on the slope, has undergone differential settlement. This settlement has caused overall rotation and deformation of the wall, consequently altering its original geometric form.

4.2. Hydrological Driving Mechanism of Pathology Differentiation

The spatial differentiation patterns of surface pathologies closely correlate with geometric anomalies. The severe undercutting in Section A aligns with its poorest surface flatness. Together, they indicate severe structural degradation in this section. The gradient change in pathology types—from undercutting-dominated to biology-dominated—suggests fundamental differences in the physical mechanisms driving wall deterioration across space.

Thermal analysis provides key moisture distribution evidence explaining these differences. Infrared thermography detects surface temperature variations; areas with higher moisture content typically exhibit lower surface temperatures due to evaporative cooling and higher thermal inertia, which delays daytime heating and nighttime cooling [

30]. The undercutting areas in Section A show strong spatial coincidence with distinct low-temperature zones. This directly confirms serious internal water infiltration in this region. Combined with its gentlest wall top slope (77%), we infer that the hydrological mechanism in Section A is infiltration-dominated. Water tends to be retained on the gentler top and subsequently infiltrates into the wall interior. Through secondary processes like freeze–thaw cycles or salt crystallization, this generates substantial physical stress from within, ultimately leading to severe undercutting.

In this study, infrared thermography served as the primary indirect method for inferring subsurface moisture distribution patterns. While direct methods (e.g., moisture meters, microwave sensing) could provide punctual validation, the employed pre-dawn acquisition protocol (

Section 2.2) is established in heritage diagnostics to maximize the thermal contrast caused by moisture, providing a reliable, non-invasive, and full-field assessment suitable for spatial correlation analysis [

31].

In contrast, the steep slopes (86%) in Sections B and C promote rapid rainwater runoff. However, the adjacent Na Tcha Temple building significantly influences this natural hydrological process near Section C. Concentrated drainage from the temple roof directly impacts the upper part of the wall. Combined with the wall’s own steep slope facilitating rapid water flow, these factors create a persistently moist surface environment on Section C. This runoff-dominated hydrological mechanism provides ideal conditions for the proliferation of organisms such as mosses and lichens. Consequently, Section C exhibits a very high proportion of surface biological pathologies. The thermal imaging data served as direct evidence of moisture distribution. It effectively validated the hydrological pathways inferred from the point cloud geometric analysis.

4.3. Comprehensive “Geometry-Hydrology-Pathology” Mechanism Model

This study reveals a clear “geometry-hydrology-pathology” causal chain. A coherent closed-loop mechanism model is proposed to elucidate the entire process of the rammed earth wall’s differential deterioration.

The mechanism chain originates from differential settlement. This root cause is supported by topographic evidence showing an overall “left-low, right-high” tilt (settlement on Section A’s side). The settlement first causes systematic changes in the geometric morphology of Section A. These changes manifest as a gentler wall top slope and worsened wall surface flatness.

This geometric transformation directly controls the spatial differentiation of hydrological pathways. In Section A, the gentle slope promotes internal water infiltration. In the steeper Sections B & C, water primarily flows as surface runoff. These two distinct hydrological patterns ultimately drive contrasting pathology modes. Internal infiltration in Section A causes structural damage, represented by undercutting. Surface runoff in Sections B & C, intensified by drainage from the Na Tcha Temple roof, leads to surface pathologies dominated by biological colonization on the upper wall.

This study reveals a key causal chain that explains why different sections of the same wall deteriorate in distinct ways. The process follows three sequential steps: (1) changes in wall Geometry directly control (2) rainwater movement (Hydrology), which then determines (3) the type of Surface Damage (Pathology) that develops. The integrated model below synthesizes our evidence to trace this complete “Geometry-Hydrology-Pathology” pathway for each wall section.

As shown in

Figure 13, the mechanism develops in three steps:

Step 1 (Trigger–Geometry Change): Differential foundation settlement under Section A initiated the process. This primary trigger was identified from geometric data (gentler slope, poor flatness, and systematic tilt). The settlement changed the wall’s original form.

Step 2 (Driver–Hydrological Divergence): The changed geometry redirects rainwater flow. In Section A, the flatter top retains water, promoting infiltration into the wall core. In Sections B & C, the steeper top sheds water, promoting surface runoff. Drainage from the adjacent temple further wets the surface of Section C.

Step 3 (Outcome–Pathological Differentiation): These water patterns cause different damages. Internal infiltration in Section A leads to sub-surface erosion (undercutting). Prolonged surface wetness in Section C encourages biological colonization. Thus, a single cause (settlement) leads to two distinct surface deterioration patterns.

4.4. Surface Protection Measures

The “geometry-hydrology-pathology” causal chain elucidated in this study provides a scientifically grounded framework for conservation decision-making. It enables a shift from generic treatments to strategies differentiated by the specific deterioration mechanisms identified in each wall section. The findings directly inform the selection and application of protective coatings.

For Section A (Infiltration-Driven Structural Damage), the priority is to reduce water ingress and consolidate the weakened matrix. Protective interventions should employ hydrophobic or pore-blocking consolidants [

37,

38], with key performance indicators being water repellency efficacyand consolidation depth.

For Section C (Runoff-Driven Biological Colonization), the goal is to inhibit biological growth on the frequently wet surface. Strategies should focus on biocidal or anti-fouling coatings [

39,

40], where biocidal longevity and resistance to wash-off are critical metrics.

For Section B (Transitional Zone), an intermediate or hybrid strategy, potentially involving coatings with both consolidating and mild biocidal properties, may be appropriate.

Translating this diagnostic framework into sustainable practice requires addressing key implementation considerations [

41]:

Material Compatibility: Any coating must be assessed for physical and chemical compatibility with the historic rammed earth to avoid adverse effects like moisture entrapment [

39].

Performance Validation: Proposed coatings require validation through laboratory accelerated aging tests (simulating Macao’s climate) and long-term in situ monitoring [

42] to confirm real-world effectiveness and durability.

Reversibility and Monitoring: Interventions should be reversible where possible. Integrating the TLS and thermal imaging methodology from this study into a long-term monitoring program [

43] would enable quantitative assessment of treatment outcomes.