Weathering and Restoration of Traditional Rammed-Earth Walls in Fujian, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Research Purpose

- (1)

- What are the key mineralogical and elemental components of the rammed-earth walls at Zishantang, and how do they reflect local construction materials and techniques?

- (2)

- How does environmental exposure—particularly varying orientations and indoor/outdoor conditions—influence the degree of microstructural degradation observed in different sections of the wall?

- (3)

- What role does the traditional soot ash coating (“Wu-yan-hui” a traditional soot–lime protective coating widely used on Fujian earthen buildings) play in mitigating weathering, and how effective is it as a sacrificial protective layer?

- (4)

- Based on scientific evidence, what relocation and restoration strategies can be developed to preserve the material and cultural authenticity of Zishantang during and after its displacement?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Subject: Rammed-Earth Walls of Qing Dynasty Dwellings Zishantang

2.2. Research Sample Collection

2.3. Research Method

2.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

2.3.2. SEM-EDS Mapping and Point Analysis

2.3.3. XRD Mineralogical Characterization

2.3.4. Raman Spectroscopy

3. Results

3.1. Comparison Results of Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

3.1.1. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Morphology

3.1.2. SEM-EDS Mapping Analysis

3.1.3. SEM-EDS Point Analysis

3.2. XRD Mineralogical Characterization Analysis

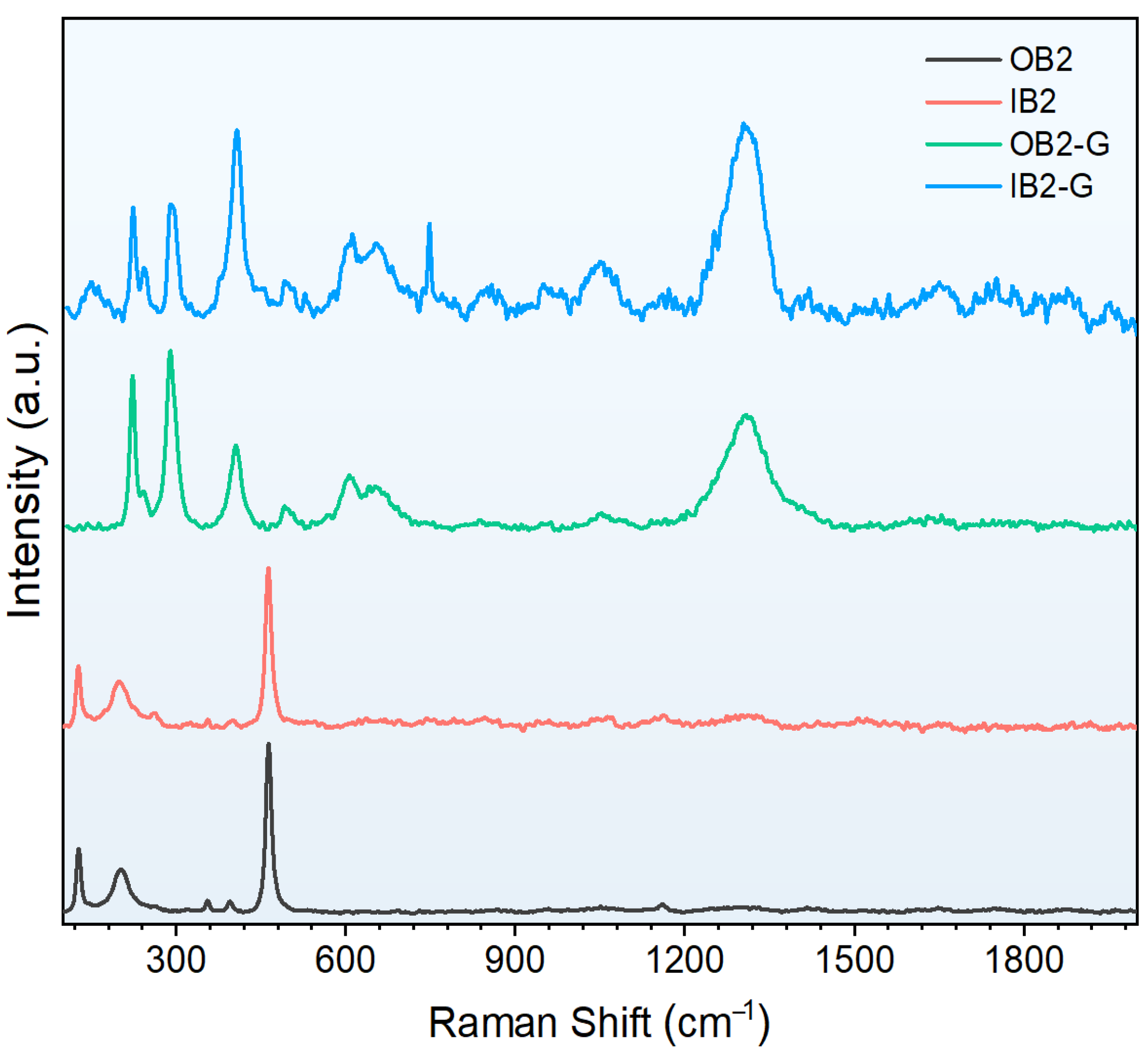

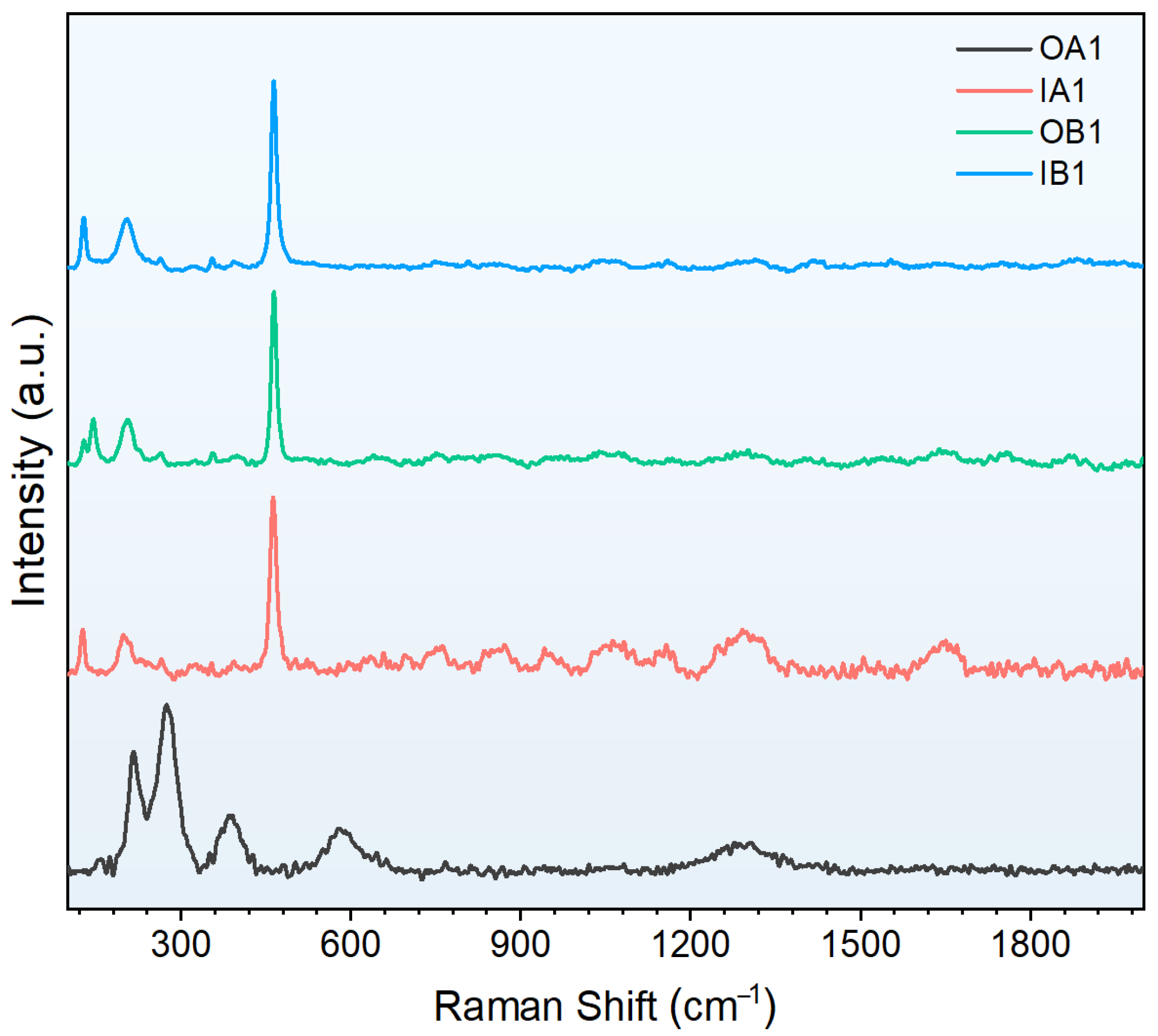

3.3. Raman Analysis

4. Discussion: Materials, Damage Conditions and Conservation Strategies for Rammed-Earth Walls

4.1. Causes of Weathering of Rammed-Earth Walls

4.2. Recommendations for Relocation and Restoration

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Jaquin, P.A.; Augarde, C.E.; Gerrard, C.M. Chronological Description of the Spatial Development of Rammed Earth Techniques. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2008, 2, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Wang, D.; Zhao, H.; Gao, J.; Gallo, T. Architectural Energetics for Rammed-Earth Compaction in the Context of Neolithic to Early Bronze Age Urban Sites in Middle Yellow River Valley, China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2021, 126, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriset, S.; Rakotomamonjy, B.; Gandreau, D. Can Earthen Architectural Heritage Save Us? Built Herit. 2021, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, R.; Chen, P.; Aoki, N. Conceptual Changes and Controversies in Rural Historical Building Relocation in China under the Heritage Adaptive Reuse Discourse. Built Herit. 2025, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Martínez, P. From Verifiable Authenticity to Verisimilar Interventions: Xintiandi, Fuxing SOHO, and the Alternatives to Built Heritage Conservation in Shanghai. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 1055–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J. Reconsidering Relocated Buildings: ICOMOS, Authenticity and Mass Relocation 1. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2008, 14, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.W. Sustainability and Variability of Korean Wooden Architectural Heritage: The Relocation and Alteration. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallipoli, D.; Bruno, A.W.; Bui, Q.-B.; Fabbri, A.; Faria, P.; Oliveira, D.V.; Ouellet-Plamondon, C.; Silva, R.A. Durability of Earth Materials: Weathering Agents, Testing Procedures and Stabilisation Methods. In Testing and Characterisation of Earth-Based Building Materials and Elements: State-of-the-Art Report of the RILEM TC 274-TCE; Fabbri, A., Morel, J.-C., Aubert, J.-E., Bui, Q.-B., Gallipoli, D., Reddy, B.V.V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 211–241. ISBN 978-3-030-83297-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; He, B.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Bai, X.; Ma, F.; Han, P.; Lu, Y.; Ren, Y. Basal Scouring in Historical Rammed Earth Sites: Formation and Height Prediction. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, F.; Puertas, E.; Gallego, R. Characterization of the Mechanical and Physical Properties of Stabilized Rammed Earth: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 325, 126693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaei, A.; Mosaddegh, A.; Hemmati, M.; Fahimifar, A. Stabilization of Rammed Earth with Waste Materials for Sustainable Construction under Rainfall Conditions: With Consideration of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Dev. Built Environ. 2025, 23, 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ye, C.; Zhong, H.; Ni, P.; Li, W.; Zeng, Z. Pullout Capacity at the Bamboo Reinforcement-Compacted Earth Interface. Geosynth. Int. 2024, 32, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yang, M.; Ni, P.; Peng, X.; Yuan, X. Degradation of Rammed Earth under Wind-Driven Rain: The Case of Fujian Tulou, China. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 119989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, W.M.; Chen, B.; Chen, Y.G.; Ye, B. Desiccation of NaCl-Contaminated Soil of Earthen Heritages in the Site of Yar City, Northwest China. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 124–125, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, B.; Tang, C. Surface Weathering Process of Earthen Heritage under Dry-Wet Cycles: A Case Study of Suoyang City, China. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 17, 5224–5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y. Assessment of Architectural Typologies and Comparative Analysis of Defensive Rammed Earth Dwellings in the Fujian Region, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yin, B.; Peng, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L. Wind-Rain Erosion of Fujian Tulou Hakka Earth Buildings. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Peng, X.; Wu, R.; Shao, K. Study on wind-driven and rain-induced erosion damage prediction of rammed earth walls in Fujian Tulou. J. Nat. Resour. 2012, 6, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Zhou, P.; Ni, P.; Peng, X.; Ye, J. Degradation of Rammed Earth under Soluble Salts Attack and Drying-Wetting Cycles: The Case of Fujian Tulou, China. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 212, 106202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, L. Artificial Intelligence for Routine Heritage Monitoring and Sustainable Planning of the Conservation of Historic Districts: A Case Study on Fujian Earthen Houses (Tulou). Buildings 2024, 14, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baera, C.; Gruin, A.; Enache, F.; Bolborea, B.; Chendes, R.V.; Ciobanu, A.; Varga, L.; Sandu, I.; Corbu, O. Opportunities regarding the innovative conservation of the romanian vernacular urbanistic heritage. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2023, 14, 913–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Dong, W.; Cui, K.; Chen, W.; Yang, W. Research Progress on the Development Mechanism and Exploratory Protection of the Scaling off on Earthen Sites in NW China. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2023, 66, 2183–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bai, X.; Li, H.; Zuo, J.; Li, D.; Han, P.; He, B. Research on Microstructure and Porosity Calculation of Rammed Soil Modified by Lime-Based Materials: The Case of Rammed Earth of Pingyao City Wall, a World Heritage Site. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losini, A.E.; Grillet, A.-C.; Woloszyn, M.; Lavrik, L.; Moletti, C.; Dotelli, G.; Caruso, M. Mechanical and Microstructural Characterization of Rammed Earth Stabilized with Five Biopolymers. Materials 2022, 15, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parracha, J.L.; Silva, A.S.; Cotrim, M.; Faria, P. Mineralogical and Microstructural Characterisation of Rammed Earth and Earthen Mortars from 12th Century Paderne Castle. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 42, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, L.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, R.; Huang, L.; Zhang, J.; Yan, B.; Chen, Z. Corrosion Analysis of Bronze Arrowheads from the Minyue Kingdom Imperial City Ruins. Coatings 2025, 15, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; He, B.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Bai, X.; Ma, F.; Han, P. Unveiling the deterioration formation process of the rammed earth city wall site of the Ancient City of Pingyao, a World Heritage Site: Occurrence, characterizations, and historic environmental implications. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2024, 16, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Bai, X.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, F.; Han, P. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Investigation and Results Interpretation of Rammed Earth from Pingyao Ancient City Walls (UNESCO World Heritage Site) Under freeze-Thaw Cycles. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S. Construction techniques of ancient building walls in Fuzhou. Cult. Relics Apprais. Apprec. 2024, 19, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Largest Single Ancient Building in Fuzhou’s Urban Area Will Be Renovated: The Chen Family Mansion “Moves”-Famous City Protection, by Fuzhou Historical and Cultural City Management Committee. Available online: https://www.fuzhou.gov.cn/zgfzzt/lswhmcgwh/zwgk/ztzl/bhqy/202112/t20211220_4272871.htm (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Qiu, R.; Guan, R. A comparison of architectural features of Fuzhou Chaibancuo and courtyard-style mansions. Huazhong Archit. 2025, 1, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q. Research on Survey and Design in the Conservation Engineering of Cultural Relics and Buildings. Constr. Budget. 2024, 6, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuzhou Residential Construction Technology; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016; ISBN 978-7-112-19378-3.

- Ding, Y.; Guan, R.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, C. Durability Analysis of Brick-Faced Clay-Core Walls in Traditional Residential Architecture in Quanzhou, China. Coatings 2025, 15, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SY/T 5163-2018; Analysis Method for Clay Minerals and Ordinary Non-Clay Minerals in Sedimentary Rocks by X-Ray Diffraction. Petroleum Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Fuzhou City Annals (Volume 1). Available online: https://data.fjdsfzw.org.cn/2016-09-18/content_462.html (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Wang, K.; Cao, J.; Ye, J.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, X. Discrete element analysis of geosynthetic-reinforced pile-supported embankments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Yang, S. Analysis of Rammed Earth Wall Erosion in Traditional Village Dwellings in Zhuhai City. Coatings 2025, 15, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.; Chen, R.; Yang, S. Experimental Study on the Anti-Erosion of the Exterior Walls of Ancient Rammed-Earth Houses in Yangjiatang Village, Lishui. Coatings 2025, 15, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Barzngy, M.Y.M.; Khayat, M. Post-conflict safeguarding of built heritage: Content analysis of the ICOMOS Heritage at Risk Journal, 2000–2019. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | Wall Position | Orientation | Exposure Condition | Coating Condition | Notes (from Your Manuscript) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IB1 | Interior Section 1 | East-facing wall | Low exposure (sheltered) | No coating | Cut at 10 mm depth; reference interior material condition |

| OB1 | Exterior Section 1 | East-facing wall | High exposure (wind–rain) | No coating | Exhibits significant surface weathering |

| IB2 | Interior Section 2 | East-facing wall | Low exposure | No coating | Paired comparison sample with IB2-G |

| OB2 | Exterior Section 2 | East-facing wall | High exposure | No coating | Paired comparison sample with OB2-G |

| IB2-G | Interior Section 2 | East-facing wall | Low exposure | With soot–lime coating (“Wu-yan-hui”) | Shows transitional microstructure; coating partially preserved |

| OB2-G | Exterior Section 2 | East-facing wall | Very high exposure | With soot–lime coating (“Wu-yan-hui”) | Surface microstructure markedly different due to coating; sacrificial layer thinning |

| Method | Purpose in This Study | What It Reveals About the Material (Based on Your Results) |

|---|---|---|

| SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy) | Visualize microstructure, pore development, particle bonding, and deterioration morphology. | Exposed samples (e.g., OB1, OB2) show increased porosity, loose particle packing, and microcracks. Interior samples (IB1, IB2) show denser, more compact structure. Soot-coated samples (OB2-G, IB2-G) display better-preserved surface microstructure and coating-induced densification. |

| EDS (Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy) | Quantify elemental composition and detect weathering-related elemental loss or enrichment. | Consistent O–Si–Al patterns across samples indicate typical silicate earth composition. Exposed samples show minor surface depletion of Si/Al relative to interior samples. Coated samples exhibit carbon-rich surface layers, confirming soot–lime film. |

| XRD (X-ray Diffraction) | Identify mineral phases and detect changes due to weathering. | Dominant minerals include quartz, feldspar (microcline/orthoclase), and clay minerals. Weathered exterior samples show weakened peaks, indicating surface mineral degradation. Coated samples’ XRD signals are partially masked by the carbonized soot layer. |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Detect carbon-based soot components and characterize coating composition. |

|

| Sample | Elemental Composition (O/Si/Al) | Dominant Minerals (XRD) | Raman Peaks (cm−1) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA1 | O: High, Si: High, Al: Moderate | Quartz, Microcline | ~465, ~610 | High porosity, loose matrix, indicative of weathering or weak compaction |

| IA1 | O: High, Si: High, Al: Moderate | Quartz, Orthoclase | ~465 | Dense structure, minor cracks, moderately weathered indoor wall |

| OB1 | O: High, Si: High, Al: Moderate | Quartz, Chlorite | ~465, weak < 800 cm−1 | Loose matrix, erosion signs, exposed to weathering |

| IB1 | O: High, Si: High, Al: Moderate | Quartz, Microcline | ~465, ~610 | Stable microstructure, compact particles, indoor location |

| OB2 | O: High, Si: High, Al: Moderate | Quartz, Minor aluminosilicates | ~465, weak D-band | Severely weathered, surface cracking, stress from freeze–thaw cycles |

| IB2 | O: High, Si: High, Al: Moderate | Quartz, Kaolinite | ~465 | Moderate weathering, compacted, interior wall |

| OB2-G | O: High, Si: High, Al: Moderate | Quartz (XRD muted by coating) | ~1350 (D), ~1580 (G) | Thick carbon-rich soot coating, protective “Wu-yan-hui” sacrificial layer |

| IB2-G | O: High, Si: High, Al: Moderate | Quartz (XRD muted by coating) | ~1350 (D), ~1580 (G) | Well-preserved soot coating, better carbon signal than OB2-G (less exposed) |

| Damage Type | Observed Causes or Features | Conservation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Surface erosion and flaking | Prolonged wind-rain exposure, especially on east-facing walls | Apply or reapply traditional soot ash (“Wu-yan-hui”) coating as sacrificial layer |

| Microcracks and increased porosity | Dry–wet cycles, thermal stress, ageing | Surface consolidation using lime-based consolidants before relocation |

| Salt accumulation and efflorescence | Environmental humidity, capillary action | Conduct desalination treatments where necessary; regular maintenance of surface coatings |

| Loss of soot–ash protective coating | Weathering, rain exposure, neglect | Reconstruct coating using traditional carbon–lime mix post-relocation |

| Orientation-dependent damage | Uneven environmental exposure (e.g., wind, rainfall) | Prioritize reinforcement and shielding for vulnerable directions |

| Risk during dismantling or transport | Structural fragility, microcracking | Numbering and documentation of wall segments; protective wrapping; gentle dismantling |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lo, C.K.N.; Song, J. Weathering and Restoration of Traditional Rammed-Earth Walls in Fujian, China. Coatings 2025, 15, 1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121491

Lo CKN, Song J. Weathering and Restoration of Traditional Rammed-Earth Walls in Fujian, China. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121491

Chicago/Turabian StyleLo, Carlos Ka Nok, and Junxin Song. 2025. "Weathering and Restoration of Traditional Rammed-Earth Walls in Fujian, China" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121491

APA StyleLo, C. K. N., & Song, J. (2025). Weathering and Restoration of Traditional Rammed-Earth Walls in Fujian, China. Coatings, 15(12), 1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121491