CdSe/ZnS QDs and O170 Dye-Decorated Spider Silk for pH Sensing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

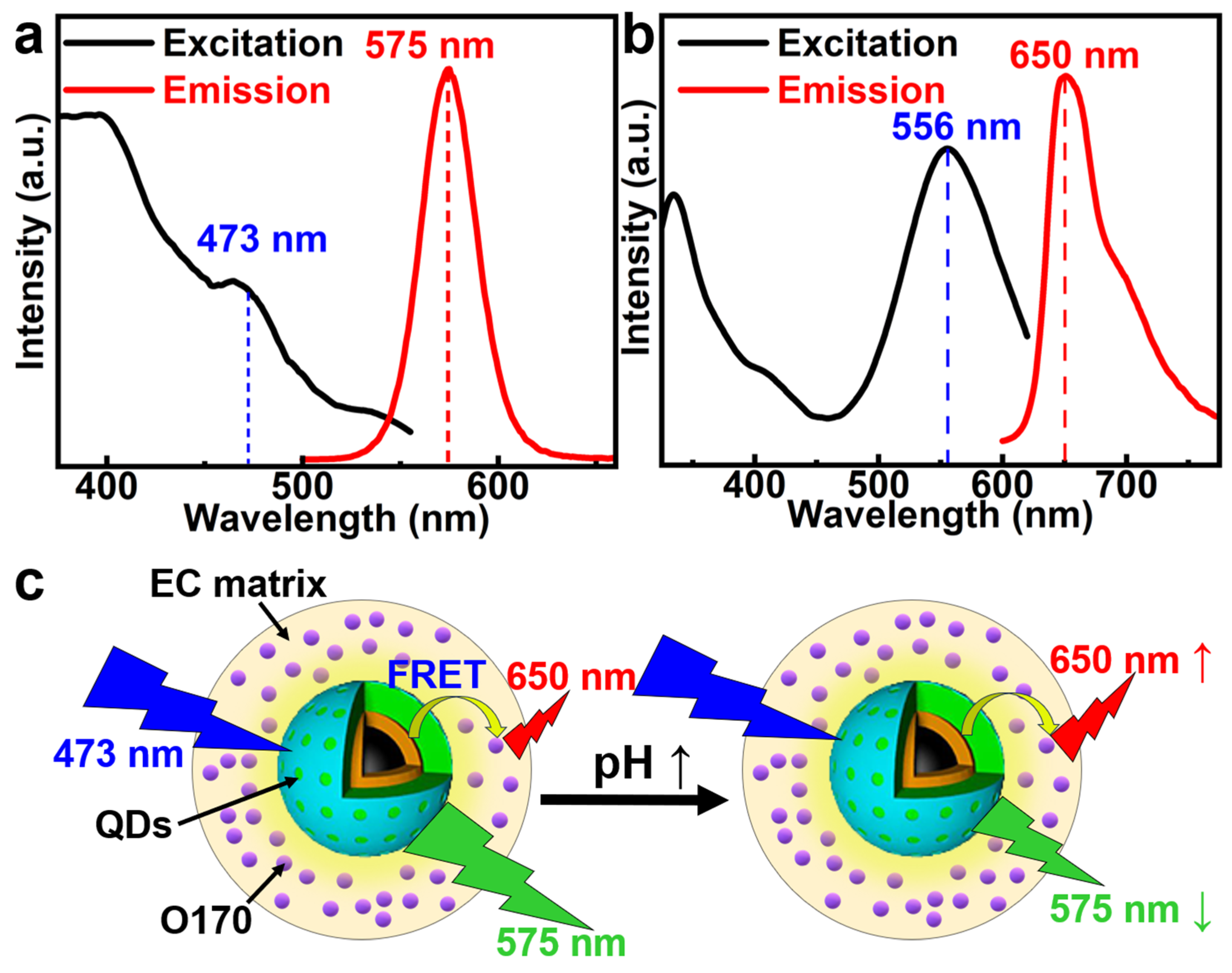

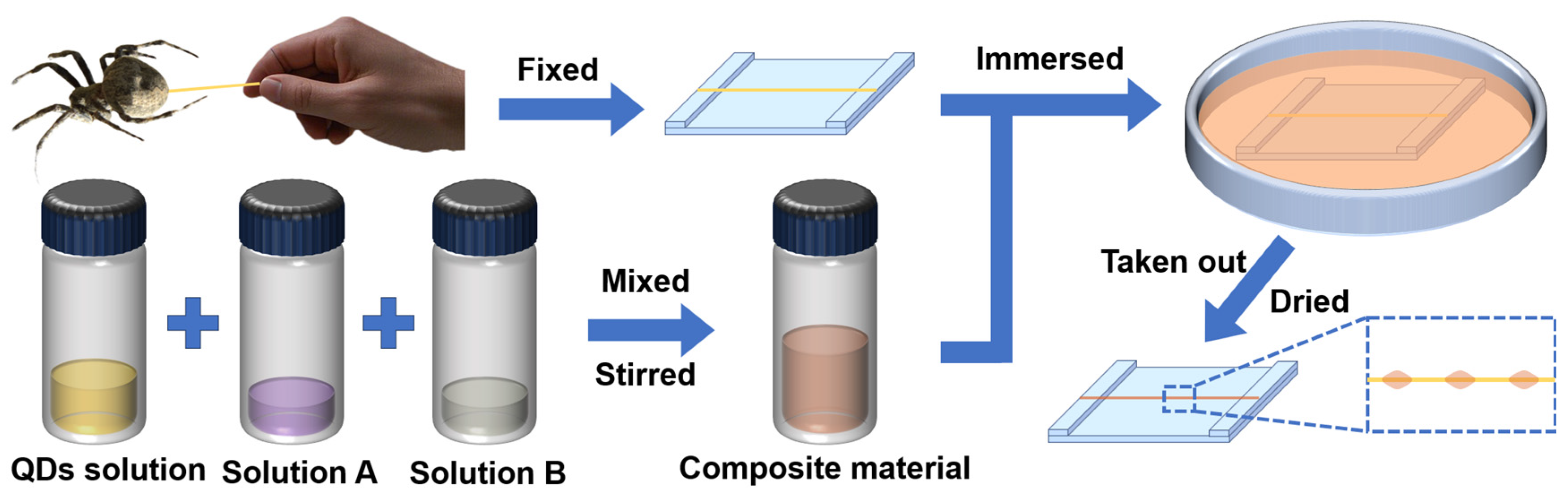

2.1. Design and Preparation of the pH Sensor

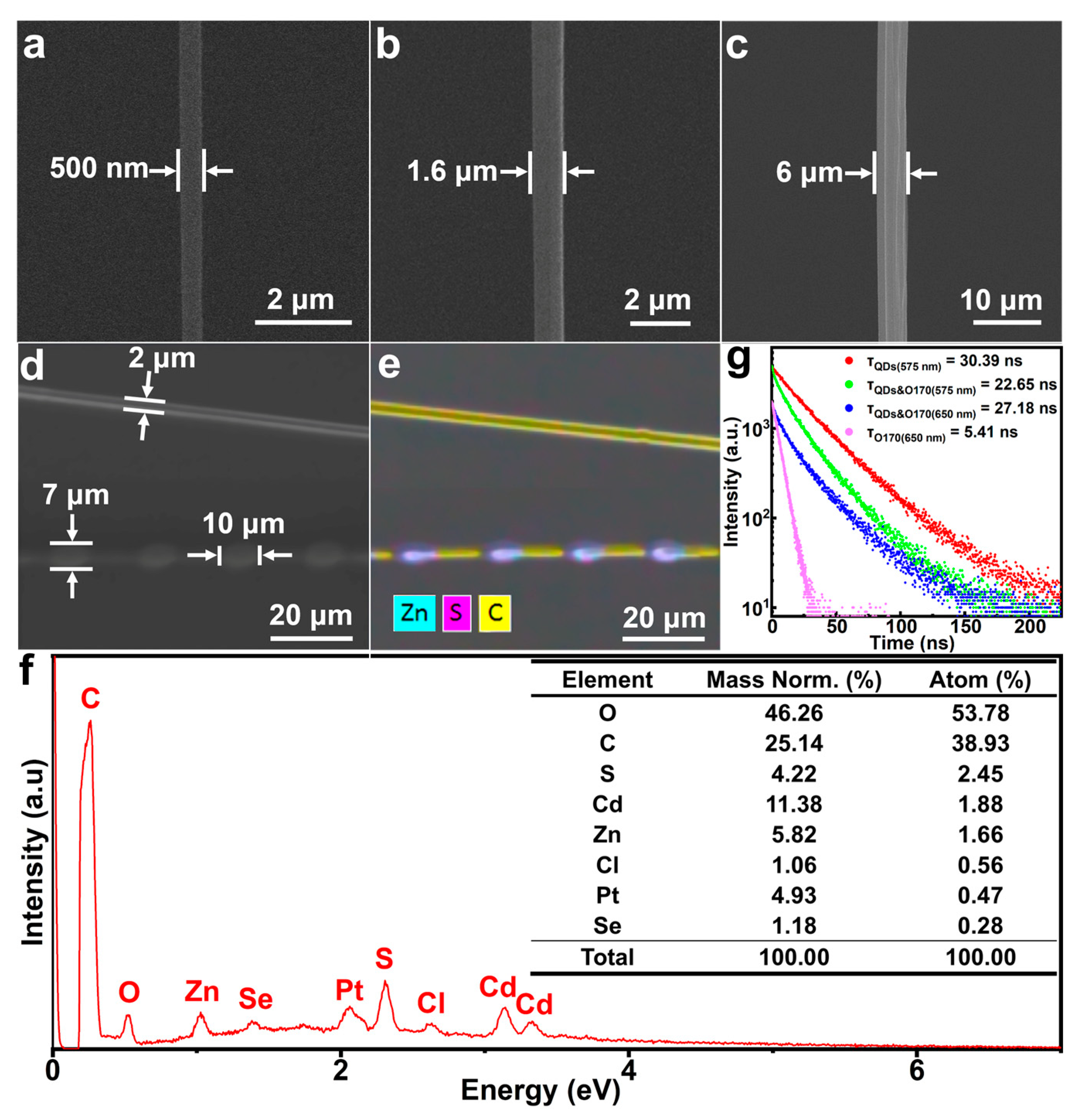

2.2. Characterization of the pH Sensor

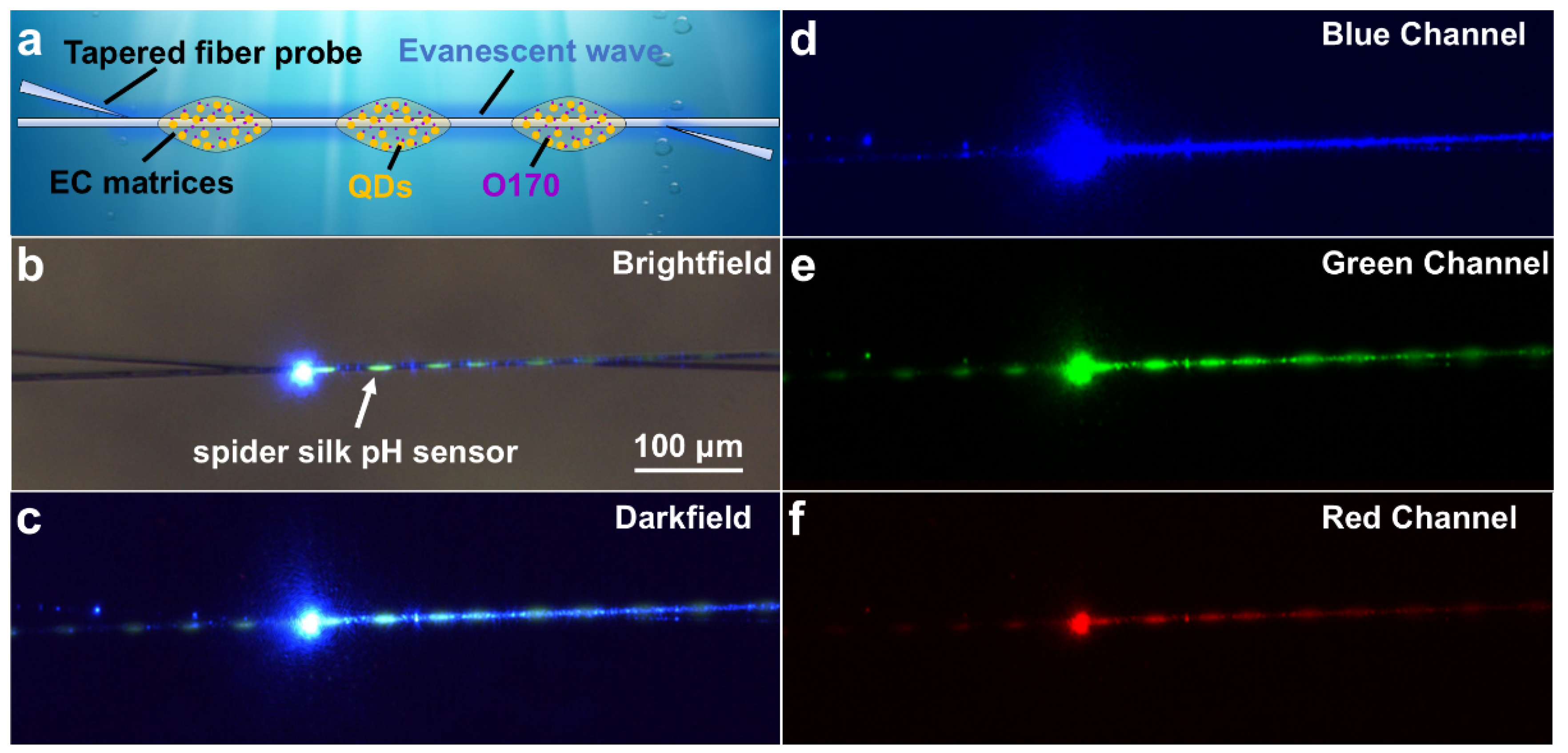

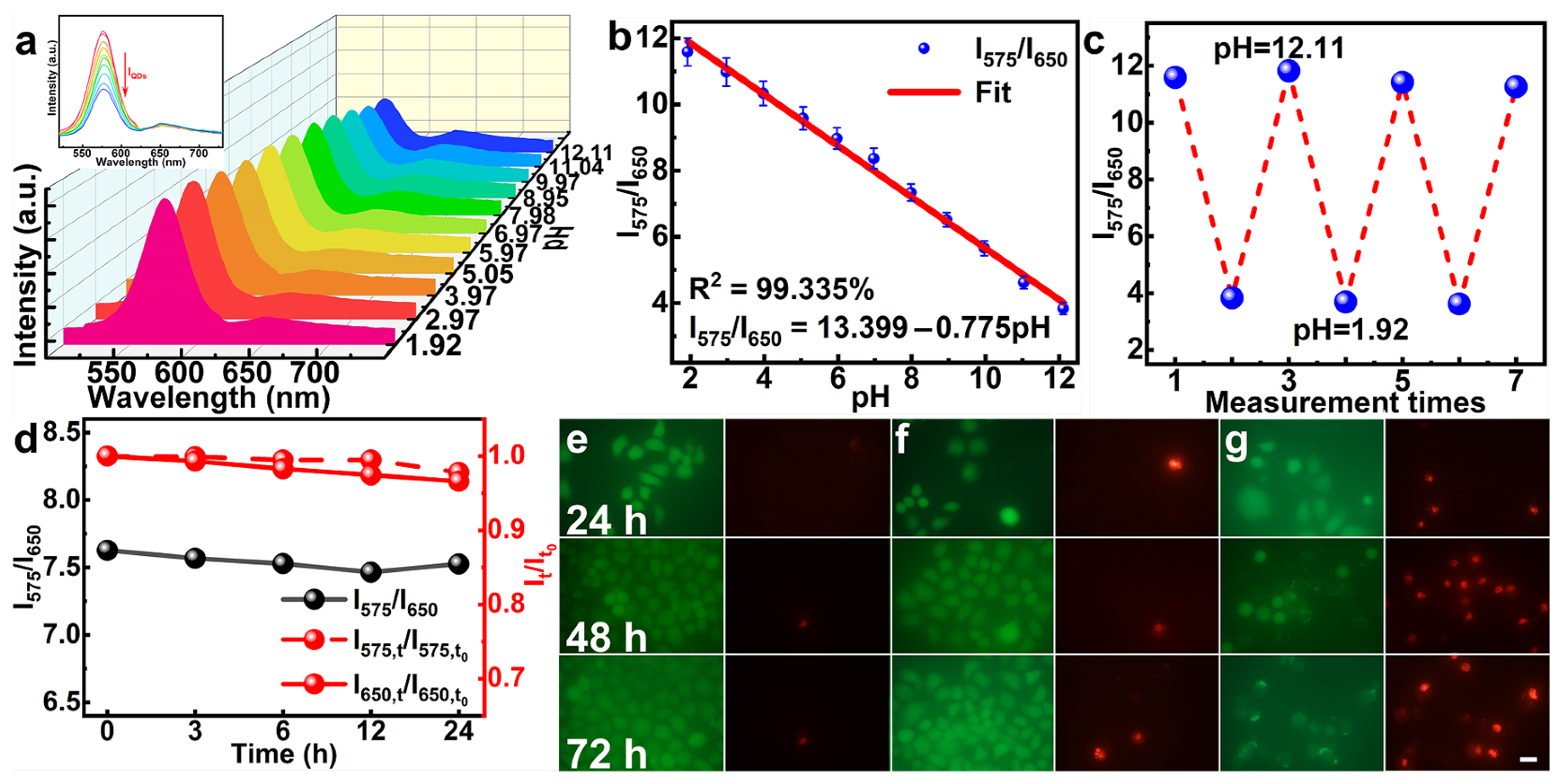

2.3. Sensing Applications of the pH Sensor

3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, N.; Zhao, L. A new fluorescent probe based on metallic deep eutectic solvent for visual detection of nitrite and pH in food and water environment. Food Chem. 2023, 398, 133935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korostynska, O.; Arshak, K.; Gill, E.; Arshak, A. Review Paper: Materials and Techniques for In Vivo pH Monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 2008, 8, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratash, O.; Buhot, A.; Leroy, L.; Engel, E. Optical fiber biosensors toward in vivo detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 251, 116088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, R.; Hu, X.; Pereira, L.; Simone Soares, M.; Silva, L.C.B.; Wang, G.; Martins, L.; Qu, H.; Antunes, P.; Marques, C.; et al. Polymer optical fiber for monitoring human physiological and body function: A comprehensive review on mechanisms, materials, and applications. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 147, 107626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Y.-n.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y. Advances in Optical Fiber Aptasensor for Biochemical Sensing Applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2300137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, S.; Gui, Y.; Wang, X.; Tian, Z.; Yu, H. Difunctional Hydrogel Optical Fiber Fluorescence Sensor for Continuous and Simultaneous Monitoring of Glucose and pH. Biosensors 2023, 13, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan Akhtar, M.; Azhar Hayat Nawaz, M.; Abbas, M.; Liu, N.; Han, W.; Lv, Y.; Yu, C. Advances in pH Sensing: From Traditional Approaches to Next-Generation Sensors in Biological Contexts. Chem. Rec. 2024, 24, e202300369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avolio, R.; Grozdanov, A.; Avella, M.; Barton, J.; Cocca, M.; De Falco, F.; Dimitrov, A.T.; Errico, M.E.; Fanjul-Bolado, P.; Gentile, G.; et al. Review of pH sensing materials from macro- to nano-scale: Recent developments and examples of seawater applications. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 52, 979–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivaldi, F.; Salvo, P.; Poma, N.; Bonini, A.; Biagini, D.; Del Noce, L.; Melai, B.; Lisi, F.; Francesco, F.D. Recent Advances in Optical, Electrochemical and Field Effect pH Sensors. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, N.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y. Optical fiber sensors for glucose concentration measurement: A review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 139, 106981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wencel, D.; Kaworek, A.; Abel, T.; Efremov, V.; Bradford, A.; Carthy, D.; Coady, G.; McMorrow, R.C.N.; McDonagh, C. Optical Sensor for Real-Time pH Monitoring in Human Tissue. Small 2018, 14, 1803627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinegger, A.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Borisov, S.M. Optical Sensing and Imaging of pH Values: Spectroscopies, Materials, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12357–12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hou, L.; Jia, D.; Yao, K.; Meng, Q.; Qu, J.; Yan, B.; Luan, Q.; Liu, T. Highly sensitive fiber-optic chemical pH sensor based on surface modification of optical fiber with ZnCdSe/ZnS quantum dots. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1294, 342281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, J.; Metternich, J.T.; Herbertz, S.; Kruss, S. Biosensing with Fluorescent Carbon Nanotubes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202112372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.-L.; Guo, F.-F.; Xu, Z.-H.; Wang, Y.; James, T.D. A hemicyanine-based fluorescent probe for ratiometric detection of ClO- and turn-on detection of viscosity and its imaging application in mitochondria of living cells and zebrafish. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 383, 133510. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Sun, D.-W.; Wu, Z.; Pu, H.; Wei, Q. On-off-on fluorescent nanosensing: Materials, detection strategies and recent food applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, R.; Jin, H. Organic fluorophores-based molecular probes with dual-fluorescence ratiometric responses to in-vitro/in-vivo pH for biosensing, bioimaging and biotherapeutics applications. Talanta 2024, 275, 126171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Yang, L.; Ye, Z.; Tang, Y.; Ouyang, H.; Yang, G.; Lei, H. CdSe/ZnS quantum dots-doped polymer optical fiber microprobe for pH sensing. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 2475–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Jiang, X.-F.; Zhang, G.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Hu, X.; Chen, M.; Wang, T.; Luo, A.; Ho, H.-P.; et al. Surface-plasmon-enhanced optical formaldehyde sensor based on CdSe@ZnS quantum dots. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Fu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H. Ratiometric fluorescent capillary sensor for real-time dual-monitoring of pH and O2 fluctuation. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 327, 125388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsipur, M.; Babaee, E.; Gholivand, M.-B.; Molaabasi, F.; Hajipour-Verdom, B.; Sedghi, M. Intrinsic dual emissive insulin capped Au/Ag nanoclusters as single ratiometric nanoprobe for reversible detection of pH and temperature and cell imaging. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 250, 116064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Aveiga, M.G.; Ramos, M.D.F.; Núnez, V.M.; Vallvey, L.F.C.; Casado, A.G.; Medina Castillo, A.L. Portable fiber-optic sensor for simple, fast, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly quantification of total acidity in real-world applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 417, 136214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lan, N.; Cheng, Z.; Jin, F.; Song, E.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.-Z.; Cai, X.; Ran, Y.; et al. In vivo fiber-optic fluorescent sensor for real-time pH monitoring of tumor microenvironment. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, S.; Tu, X.; Zhang, X. Skin-attachable Tb-MOF ratio fluorescent sensor for real-time detection of human sweat pH. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 263, 116606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Shao, S.; Wu, B.; Miki, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Harada, H.; Ohe, K. Fast tumor imaging using pH-responsive aggregation of cyanine dyes with rapid clearance. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 413, 135876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Sun, S.; Xu, Y. A hydrogel sensor based on cellulose nanofiber/polyvinyl alcohol with colorimetric-fluorescent bimodality for non-invasive detection of urea in sweat. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Terreno, E. Development of a versatile optical pH sensor array for discrimination of anti-aging face creams. Talanta 2024, 278, 126447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.A.M.; Awang, N.A.; Talip, B.A.; Zalkepali, N.U.H.H.; Supaat, M.I. Highly sensitive adulteration detection in kelulut honey utilizing fiber Bragg grating technology with Q-switched pulse erbium-doped fiber laser and innovative spider silk substrate. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 376, 115656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendra, Y.H.; Heah, W.Y.; Malay, A.D.; Numata, K.; Yamamoto, Y. Micrometer-Scale Optical Web Made of Spider Dragline Fibers with Optical Gate Operations. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2023, 11, 2202563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Yuan, L. Spider Silk as a Flexible Light Waveguide for Temperature Sensing. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 41, 1884–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Y.; Wen, M.; Yao, B.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, W.; Lei, H. Metal-Nanostructure-Decorated Spider Silk for Highly Sensitive Refractive Index Sensing. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, D.J.; Kane, D.M. Investigating the transverse optical structure of spider silk micro-fibers using quantitative optical microscopy. Nanophotonics 2017, 6, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, P.; Yang, G.; Lei, H. Single Polylactic Acid Nanowire for Highly Sensitive and Multifunctional Optical Biosensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 27983–27990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Wu, T.; Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Upconversion Nanoparticle Decorated Spider Silks as Single-Cell Thermometers. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, H.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. p-Aminothiophenol-coated CdSe/ZnS quantum dots as a turn-on fluorescent probe for pH detection in aqueous media. Talanta 2017, 166, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Kamimura, T.; Uegaki, K.; Biju, V.; Ty, J.D.T.; Shigeri, Y. Reversible photoluminescence sensing of gaseous alkylamines using CdSe-based quantum dots. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 246, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jin, Q.; Song, X.; Li, H.; Jia, D.; Liu, T. Oxazine-functionalized CdSe/ZnS quantum dots for photochemical pH sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 10996–11006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Lei, H.; Li, B. Temperature-dependent Förster resonance energy transfer from upconversion nanoparticles to quantum dots. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 12450–12459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, A.; Zafar, H.; Sherwani, A.; Mohammad, O.; Khan, T.A. Synthesis, characterization and in vitro anticancer activity of 18-membered octaazamacrocyclic complexes of Co(II), Ni(II), Cd(II) and Sn(II). J. Mol. Struct. 2014, 1075, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.-L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, K.-P.; Niu, S.-Y.; Zong, Q.-S.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Z.-Q. Monitoring intracellular pH using a hemicyanine-based ratiometric fluorescent probe. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 284, 121778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, F.; Long, X.; Lv, X.; Du, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Bai, T.; Xing, S. Bicomponent-quantum-dots based ratiometric fluorescence pH sensing platform constructed through placing in close proximity strategy for multiple bio-applications. Microchem. J. 2025, 217, 115092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ren, Y.; Nie, Y.; Jin, C.; Park, J.; Zhang, J.X.J. Dual fluorescent hollow silica nanofibers for in situ pH monitoring using an optical fiber. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 2180–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| pH Probe | Sensing Range | Sensitivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnCdSe/ZnS QDs-modified tapered optical fiber | 6.00–9.01 | 0.139/pH | [13] |

| Insulin-capped Au–Ag nanocluster | 6.00–9.00 | 0.795/pH | [21] |

| Tb MOF (metal–organic framework) | 4.12–7.05 | 0.806/pH | [24] |

| Hemicyanine-based ratiometric fluorescent probe | 6.00–8.00 | 0.890/pH | [40] |

| Glutathione-capped CuInS2/ZnS and MoS2 QDs | 3.00–8.00 | 0.297/pH | [41] |

| Dual fluorescent (Fluorescein isothiocyanate and tris(2,2′-bipyridyl) dihlororuthenium(II) hexahydrate) doped hollow silica nanofibers | 4.00–9.00 | 0.248/pH | [42] |

| CdSe/ZnS QDs and O170 dye decorated spider silk | 1.92–12.11 | 0.775/pH | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, R.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Yu, P.; Yang, G.; Lei, H. CdSe/ZnS QDs and O170 Dye-Decorated Spider Silk for pH Sensing. Coatings 2026, 16, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010110

Tang Y, Zhang H, Xiao R, Wu Q, Zhang J, Liu C, Yu P, Yang G, Lei H. CdSe/ZnS QDs and O170 Dye-Decorated Spider Silk for pH Sensing. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010110

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Yangjie, Hao Zhang, Ran Xiao, Qixuan Wu, Jie Zhang, Chenchen Liu, Peng Yu, Guowei Yang, and Hongxiang Lei. 2026. "CdSe/ZnS QDs and O170 Dye-Decorated Spider Silk for pH Sensing" Coatings 16, no. 1: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010110

APA StyleTang, Y., Zhang, H., Xiao, R., Wu, Q., Zhang, J., Liu, C., Yu, P., Yang, G., & Lei, H. (2026). CdSe/ZnS QDs and O170 Dye-Decorated Spider Silk for pH Sensing. Coatings, 16(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010110