1. Introduction

With the rapid development of nanophotonics, researching functional optical phenomena has received unprecedented focus [

1,

2,

3]. Optical bistability (OB), a compelling optical phenomenon with substantial fundamental research significance, has been demonstrated to holds great potential for practical applications in fields including optical switching and optical memory devices. A substantial amount of theoretical and experimental work has been conducted on OB in various systems including graphene-based structures [

4,

5], optomechanical systems [

6,

7], and waveguide [

8,

9]. Among these, a hybrid system composed of semiconductor quantum dots (SQDs) and metal nanoparticles (MNPs) has garnered growing interest due to its distinctive optical bistable properties. Artuso and Bryant demonstrated that further increasing the sizes of both the SQD and MNP leads to strengthened coupling, thereby revealing a bistable operational regime [

10]. Malyshev et al. showed that OB becomes discernible when the optical hysteresis of Rayleigh scattering is measured [

11]. Li et al. found that the bistable nonlinear absorption response is observable and the corresponding bistable region can be precisely modulated by tailoring the size of the MNP, the interparticle distance, and the intensity of control field [

12]. Nugroho et al. achieved both the construction of 2D bistability phase diagrams within the system’s parameter space and the visualization of the switching process between the lower and upper stable branches [

13]. Asadpour and Rahimpour Soleimani demonstrated that a 2D array of metal-coated dielectric nanospheres embedded in a unidirectional ring cavity exhibits both OB and optical multistability (OM) behaviors [

14]. Paspalakis et al. showed that the optical rectification of this hybrid system is bivalued, with a bistable behavior manifesting alongside it [

15]. Mohammadzadeh and Miri established that the fluorescence spectrum and the intensity–intensity correlation function can be substantially tailored in the regions exhibiting bistability [

16]. Zhao et al. investigated OB enabled by multipole polarizations in an SQD-MNP hybrid system, and their findings reveal that multipole effects lead to significant broadening of the pump intensity-dependent bistable region under strong exciton–plasmon coupling [

17]. They further demonstrated that, for a given intermediate scaled pumping intensity in an SQD–metallic nanoshell (MNS) hybrid system, multipole polarizations not only narrow the bistable zone but also enlarge the corresponding thresholds [

18].

In our previous work [

18], we systematically explored the dependence of OB on the dielectric shell thickness of the MNS. He and Zhu proposed a highly sensitive method for cancer cell detection based on a peptide QD–cell membrane coupled system, leveraging the unique optical responses of hybrid biomaterial structures [

19]. Beyond these advances, SQD/MNP hybrid nanosystems have emerged as promising candidates for biosensing applications [

20,

21,

22]. For example, Zhao et al. demonstrated that rigid DNA spacers can bridge Ag NPs and CdS QDs, thereby enabling the targeted stimulation of exciton–plasmon interactions in photoelectrochemical systems, offering a viable mechanism for novel DNA sensing protocols [

20]. Popov et al. presented a comprehensive overview of signal amplification strategies for electrochemical immunosensors, in which MNPs and QDs act as labeling agents, with a specific focus on recent advances in the ultrasensitive detection of biomarkers [

21]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have yet focused on OB behaviors in an SQD-MNS–cell membrane. Investigating OB in this system is not only scientifically meaningful but also practically valuable. Additionally, the bistable properties in this system may enable the development of highly sensitive optical switches tailored for biomedical applications. Specifically, the synergistic coupling between the SQD, MNS, and cell membrane is expected to endow the system with enhanced optical responsiveness, which cannot be achieved by binary hybrid system alone. In the present paper, we therefore investigate the influences of key parameters (including pump intensity, interparticle distance, exciton–phonon coupling strength, and dielectric shell thickness) on the bistable effect in an SQD-MNS–cell membrane hybrid system. Particularly, we discuss the feasibility of leveraging the tunable OB behaviors of this system for cancer cell detection, aiming to provide a new theoretical basis and technical reference for the design of next-generation biosensors.

2. Theoretical Model and Method

A schematic of the SQD-MNS–cell membrane hybrid system under investigation is provided (

Figure 1) with the system being simultaneously irradiated by a strong pump field (

Epu,

ωpu) and a weak probe field (

Epr,

ωpr). The SQD is modeled as a two-level system, encompassing a ground state |

g> and a single exciton state |

e>. The exciton transition frequency is represented as

ωex. The MNS features an outer dielectric shell with radius

r1 and a metallic inner core with radius

r0, where the shell thickness is defined as Δ

r =

r1 −

r0. Specifically, adjusting the dielectric shell thickness enables precise control over the dielectric environment surrounding the metallic core, a parameter that governs the exciton–plasmon coupling efficiency in the SQD-MNS–cell membrane hybrid system. Additionally, the distance between the SQD and the MNS is denoted as

d. When radiation pressure from the strong pump field acts on the cell membrane, the membrane exhibits vibrational motion. The fundamental vibrational frequency associated with the cell membrane is given by

ωc = 1/2 × {(

ϕ/

η) × [(1/

L1)

2 + (1/

L2)

2]}

1/2 [

19], wherein

ϕ and

η stand for the average surface tension and average surface density of the cell membrane, respectively.

L1 and

L2 refer, respectively, to the length and width of the region housing the SQD. Furthermore,

ε0,

ε1,

εm,

εs, and

ε2 represent the dielectric constants of vacuum, the background medium, the metallic core, the dielectric shell, and the SQD, respectively.

Within the rotating frame, the total Hamiltonian corresponding to the SQD/MNS/cell membrane hybrid system is expressed as follows:

Here, the Hamiltonian of the exciton is denoted as

ħΔ

puσz, whereas the Hamiltonian descripting the phonon mode of the cell membrane is given by

ħωca+a. The interaction Hamiltonian between phonons and the exciton is represented by the term

ħλσzQ, and the interaction Hamiltonian governing the coupling between the exciton and the applied electric field is specified as −

μ(

Eexσeg +

Eex*

σge), where

μ represents the electric dipole moment of the SQD, and

Eex denotes the amplitude of the electric field acting on the exciton. Additionally, the phonon quadrature operator is defined as

Q =

a+ +

a, in which

a+ and

a correspond to the phonon creation and annihilation operators, respectively. The frequency detuning between the exciton and the pump field is given by Δ

pu = ω

ex − ω

pu. The transition operator

σij = |

i><

j| (where

i,

j =

g,

e) describes the transition process from the initial state |

i> to the final state |

j>. Furthermore, the coupling strength between the exciton in the SQD and the phonon modes of the cell membrane is quantified as

λ =

λ0ωc, where

λ0 is a dimensionless coupling coefficient, and

σz = (

σee −

σgg)/2 refers to the half population inversion of the exciton. The total field experienced by the exciton (i.e.,

Eex) is denoted as [

23]

Here, Λ is defined as [1 + 2

γ1(

ω)

r13/

d3]/

εeff with Λ

I = Im[Λ] and Λ

R = Re[Λ], while Θ takes the form [Σ

nn(

n + 1)(

n + 1)

2γn(

ω)

r12n+1]/[8

πε0ε1εeffd2n+4]. In these expressions,

εeff = (

ε2 + 2

ε1)/(3

ε1) [

24],

PSQD =

μσge, and

δpr =

ωpr −

ωpu represents the probe-pump detuning. Additionally, the nth order (

n = 1, 2, 3…) polarization factor

γn(

ω) reads as [

23,

25]

Using the Heisenberg equation of motion with the commutation relations including [

a,

a+] = 1, [

σge,

σz] =

σge, [

σeg,

σz] = −

σge, and [

σeg,

σge] = 2

σz [

26], the temporal evolutions of operators

σz,

σge, and

Q can be expressed as

Here, Π =

μ2Θ/

ħ is defined as the feedback parameter with Π

I = Im[Π] and Π

R = Re[Π], Γ

1 (Γ

2) denotes to the exciton relaxation (dephasing) rate,

γc refers to the decay rate of the cell membrane vibration, and Ω

pu =

μEpu/

ħ represents the Rabi frequency of the pump field.

Ipu = Ω

pu2 stands for the scaled pump intensity, where

c is the speed of light in a vacuum. The Langevin noise operator, denoted as

, satisfies the relations

and

. In addition,

corresponds to a zero-mean Brownian random force, which adheres to the correlation relation

. To solve Equations (5)–(7), the following ansatz is adopted [

26]:

σz =

σz(0) +

σz(−1)eiδprt +

σz(1)e−iδprt,

σge =

σge(0) +

σge(−1)eiδprt +

σge(1)e−iδprt, and

Q =

Q0 +

Q−1eiδprt +

Q1e−iδprt. When these expressions are substituted into Equations (5)–(7),the formula for the linear susceptibility is derived

where

w0 = 2

σz(0),

σge(0) = (Λ

I −

iΛ

R)Ω

puw0/(Γ

2 − Π

Iw0 +

iΔ

pu −

iλλ0w0 +

iΠ

Rw0),

C1 = (Γ

2 − Π

Iw0) −

i(

δpr − Δ

pu − Π

Rw0 +

λλ0w0),

C2 = (Λ

I −

iΛ

R)

μΩ

pu + (Π

I −

iΠ

R)

μσge(0) −

iλ2ζμσge(0),

C3 =

μ2(Λ

I −

iΛ

R)/

ħ,

C4 = −(4Π

Iμσge(0)* + 2

μΩ

puΛ

I) − 2

iμΩ

puΛ

R,

C5 = (−

iδpr + Γ

1)

μ2,

C6 = 2

μΩ

puΛ

I + 4Π

Iμσge(0) − 2

iμΩ

puΛ

R,

C7 = [(Γ

2 − Π

Iw0) −

i(

δpr + Δ

pu + Π

Rw0 −

λλ0w0]/[(

μΩ

puΛ

I +

μΠ

Iσge(0)*) +

i(Λ

RμΩ

pu +

μΠ

Rσge(0)* +

λ2ζμσge(0)*)],

C8 = 1/

ε0 × [

iλ2ζμσge(0) + (−Λ

I +

iΛ

R)

μΩ

pu + (−Π

I +

iΠ

R)

μσge(0)]/[(−Γ

2 + Π

Iw0) +

i(

δpr − Δ

pu − Π

Rw0 +

λλ0w0)],

C9 =

μ2/(

ε0ħ) × (−Λ

I +

iΛ

R)/[(−Γ

2 + Π

Iw0) +

i(

δpr − Δ

pu − Π

Rw0 +

λλ0w0)], and

ζ = −

ωc/(

ωc2 −

iδprγc −

δpr2). Im

χeff(1) denotes the linear absorption, and Re

χeff(1) corresponds to the dispersion.

The exciton-population inversion (

w0) can be calculated using the equation provided below

3. Results and Discussion

Subsequently, we investigate a practical hybrid system consisting of an SQD, an MNS, and a cell membrane. All parameter values employed in this study are experimentally achievable. Regarding the MNS, it comprises a Au core and a SiO

2 shell with the dielectric constant of the SiO

2 shell set to

εs = 2.16 [

27,

28], the core radius to

r0 = 12 nm. The exciton resonant frequency is chosen to 2.36 eV, which is close to the broad plasmon frequency of Au. Here,

εm denotes the dielectric constant of the Au core [

29]. Regarding the SQD, its parameters are configured as follows:

ε2 = 6,

μ = 1.0 × 10

−28 C·m, Γ

1 = 1.25 ns

−1, and Γ

2 = 3.33 ns

−1 [

30]. The phospholipid bilayer-based cell membrane is distinguished by two key vibrational parameters: a fundamental mode frequency

ωc = 4.90 MHz and a decay rate

γc = 0.04 MHz [

31]. The total system is located in an air environment with a background dielectric constant of

ε1 = 1. Additionally, the subsequent analysis focuses on the scenario where the pump and probe fields have the same frequency (i.e.,

ωpu =

ωpr).

Figure 2 illustrates the dependence of linear absorption on pump intensity for three distinct nanosystems, which are SQD, SQD-MNS, and SQD-MNS–cell membrane, under both dipole and multipole approximations. We first discuss the scenario of dipole approximation. As presented in

Figure 2a, under the dipole approximation (i.e.,

N = 1), the absorption of the SQD system weakens monotonically as the pump intensity

Ipu increases. For the SQD-MNS system, a sharp peak is observed at

Ipu = 2.2 GHz

2. This peak may be attributed to the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) of the MNS. This resonance enhances light–matter interaction at a specific pump intensity to induce a pronounced absorption maximum, and its emergence likely stems from the synergistic interaction between the excitonic transitions of the SQD and the LSPR of the MNS. The SQD-MNS–cell membrane system, however, exhibits distinctly different behavior: an interesting bistable effect occurs, suggesting the system can exist in two different absorption states when exposed to the same pump intensity. Next, we analyze the linear absorption behavior of these three systems under the multipole approximation (corresponding to

N = 12) [

Figure 2b], which accounts for higher-order multipole interactions and provides a more accurate description of light–matter interaction in complex nanostructures. The selection of a multipole order

N = 12 in the present work is based on our previously published findings [

18], where we rigorously demonstrated that optical spectral lines achieve complete convergence and overlap at

N = 7. Therefore, we have opted for

N = 12 to ensure the fulfillment of the convergence condition. Unlike the dipole approximation case, the SQD-MNS system displays an “H-shaped” bistable region due to the multipole effect, and its lower and upper bistable branches nearly overlap [Inset in

Figure 2b]. This result may stem from the spatially inhomogeneous near-field distribution around the SQD, which is induced by these high-order multipoles. Such a distribution modulates the exciton transition probability, consequently narrowing the energy gap between the two bistable states. In particular, the constructive interference between the dipole and high-order multipole fields serves to reduce the hysteresis loop width of the OB curve, driving the lower and upper branches of the bistable response toward near-overlap. For the SQD-MNS–cell membrane system, bistable behavior is observable across an extremely wide region, which suggests that OB can be easily achieved with an appropriate pump intensity. Additionally, Compared with the

N = 1 case, the bistable region for

N = 12 shifts toward higher

Ipu values. This shift implies that higher-order multipole interactions require a larger pump intensity to trigger OB, and this is an important consideration for optimizing the operating conditions of OB-based devices.

Figure 3a illustrates the variation in the linear absorption curve with pump intensity

Ipu by adjusting the spacing between the SQD and the MNS. As is all known, the exciton–plasmon interaction is strongly dependent on the interparticle spacing [

32,

33,

34]: a gradual increase in this spacing weakens the interaction, while a decrease strengthens it. For a spacing

d = 26 nm, the bistable effect is initiated when the pump intensity

Ipu rises to a critical value of 2.148 × 10

3 GHz

2; this threshold denotes the point where the bistable response of the coupled system surpasses the dominance of linear absorption. When

d increases to 30 nm, the critical

Ipu required to generate OB increases to 2.761 × 10

3 GHz

2. This observation confirms that a larger

d results in weaker exciton–plasmon coupling, which in turn requires a stronger pump intensity to induce OB. This also reveals a core relationship that underpins the tunability of bistable behavior in the SQD-MNS–cell membrane system. To further quantify the dependence of the bistable threshold on the SQD-MNS distance and provide a comprehensive visualization of parameter-space behavior, in

Figure 3b we plot a bistability phase diagram within the system’s parameter subspace [

Ipuc;

d;

N = 12; Δ

r = 2 nm;

λ = 2 GHz]. For

d = 20 nm, OB appears only when the lower bistable threshold

Ipuc0 = 6.162 × 10

3 GHz

2. However, as

d increases gradually from 20 nm,

Ipuc0 undergoes an abrupt decline. When

d reaches 22.09 nm,

Ipuc0 drops to merely 0.1 GHz

2, representing the minimum threshold for OB in this system. Notably, at this specific

d value, a narrow bistable region

Ipuc ∈ [0.1, 205.2] GHz

2 is formed, indicating that the system can only maintain bistable states within a limited range of pump intensities. When

d exceeds 22.09 nm, the lower bistable threshold further increases as

d continues to rise, as the system demands higher pump energy to sustain OB.

Inspecting Equation (9), it is evident that the bistable effect is strongly correlated with the dielectric shell thickness.

Figure 4a illustrates how the linear absorption curve varies with the interparticle distance

d for different dielectric shell thicknesses Δ

r. For a specific shell thickness (i.e., Δ

r = 2 nm), a distinct bistable effect emerges in the absorption spectrum, characterized by two bistable absorption states that respond to tuning of

d. However, as Δ

r is further increased to 4 nm, the bistable region vanishes completely and is replaced by a sharp peak precisely centered at

d = 24.72 nm. When Δ

r is increased to 6 nm, the maximum intensity of the absorption peak is significantly suppressed (by approximately 50% relative to that at Δ

r = 4 nm), and the peak profile becomes broadened, reflecting weakened exciton–plasmon interaction and increased energy dissipation in the thicker dielectric layer. To further visualize the influence of shell thickness on OB, we plot a bistability phase diagram in the parameter subspace [

dc; Δ

r;

N = 12;

λ = 2 GHz;

Ipu = 100 GHz

2]. A distinctly different scenario can be observed. Herein, a narrow bistable region appears, indicating that our proposed system can function as an optical bistable switch. To further elucidate the underlying physical properties, we divide this region into three subspaces. Specifically, in region ① (corresponding to 0 nm ≤ Δ

r ≤ 2.13 nm), the bistable switch exhibits only a single channel with one bistable region. In contrast, a dual-channel bistable state emerges in region ②, which is characterized by two independent bistable regions. When Δ

r exceeds 2.86 nm, the system enters region ③, where the bistable effect is smeared out, thereby indicating that the bistable switch is turned off. Driven by the synergistic effect of the MNS shell dielectric confinement and the exciton–phonon coupling, the sequential evolution of the system’s bistable channels with dielectric shell thickness arises from the combined effect of exciton–plasmon and exciton–phonon couplings.

In contrast to our previously published work, the cell membrane assumes a pivotal role in the proposed system. Consequently, clarifying the influence of the coupling between the cell membrane and the exciton on OB of the system holds considerable significance.

Figure 5a illustrates the variation curve of linear absorption with the exciton–phonon coupling strength

λ for different shell thicknesses Δ

r. For Δ

r = 2 nm, the absorption curve exhibits two isolated bistable regions; however, as Δ

r increases to 4 nm, these two regions shift toward larger

λ values. Especially, near the left critical point of the left bistable region, the absorption intensity is greatly suppressed compared to that observed at Δ

r = 2 nm. Unexpectedly, when Δ

r is further increased to 6 nm, these two bistable regions disappear entirely. It should be noted that the bistable effect disappears when the exciton–phonon coupling is absent (i.e.,

λ = 0 GHz) under fixed conditions. However, the bistable effect emerges once the cell membrane is incorporated into the system. In the SQD-MNS system [

18], the absence of interfacial charge transfer dynamics removes the critical support needed to sustain exciton–phonon coupling and stabilize the bistable state. In contrast, integrating the cell membrane into the system establishes such interfacial dynamics, thereby restoring both the coupling and the bistable response. These observations demonstrate that the cell membrane is an indispensable component for the precise modulation of OB. To clarify the effects of shell thickness and exciton–phonon coupling strength on the critical bistable conditions, we construct a bistability phase diagram in the parameter subspace [

λc; Δ

r;

N = 12;

d = 28 nm;

Ipu = 100 GHz

2]. In the absence of the dielectric shell (i.e., Δ

r = 0 nm), the bistable effect arises. It is not until Δ

r increases to 1.23 nm that a dual-channel bistable state begins to be observed. Specifically, for a fixed Δ

r = 1.23 nm, the bistable state can be achieved under the conditions of 0 GHz ≤

λc ≤ 0.024 GHz or 0.516 GHz ≤

λc ≤ 0.571 GHz. Consistent with the conventional definition in nanophotonic coupling systems, the weak coupling regime corresponds to

λ < Γ

1, while the strong coupling regime is demarcated by

λ > Γ

1. Our experimental results align well with this standard classification. It should be noted that the bistable state is found to be favored in the weak exciton–phonon coupling regime. As Δ

r is further increased beyond this threshold, two narrow bistable regions emerge simultaneously. Prior studies [

35,

36,

37] have demonstrated that an SiO

2 shell with a thickness under 8 nm exerts only a negligible influence on the optical properties of Au@SiO

2 core–shell NPs, implying that tuning the shell thickness across the range of 0 to 8 nm induces only a marginal change in the dielectric constant of the SiO

2 layer. Collectively, these results demonstrate that such dual-channel bistable states exist only when the coupling strength between the exciton and the cell membrane reach certain specific values, thereby offering novel insights for switching single-channel and dual-channel bistable states.

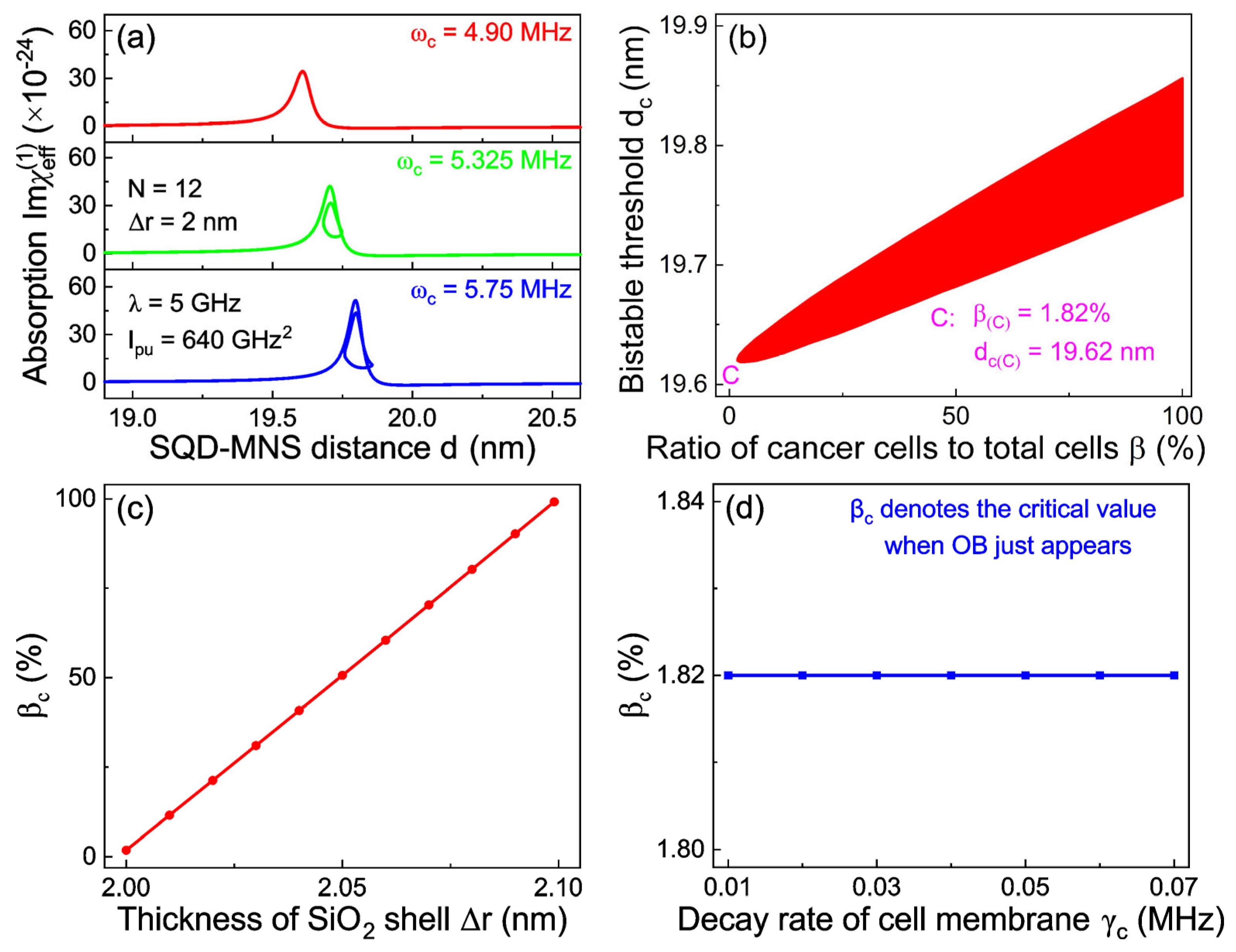

By examining Equation (9), it is evident that the vibrational frequency of the cell membrane may play a key role in regulating OB within the proposed system. As is well known, the malignant transformation of normal cells into cancer cells is accompanied by a corresponding change in their membrane vibrational frequency

ωc. Specifically, during this transformation process, the average surface tension

ϕ of the cell membrane undergoes alteration, which in turn induces a concomitant change in

ωc that conforms to the relationship:

ωc = (1 −

β)

ωc0 +

βωc1 [

38]. Herein,

ωc0 and

ωc1 correspond, respectively, to the fundamental mode vibrational frequencies of the cell membrane derived from normal and cancer cells [

19], while

β denote the ratio of cancer cells to total cells. In our model,

β increase as the fraction of normal cells undergoes malignant transformation rises. Specifically,

β = 0 corresponds to a fully normal cell membrane, whereas

β = 1 represents a completely cancerous one. When normal cells have not yet started to become cancerous, the vibrational frequency of normal cells is 4.90 MHz prior to the initiation of carcinogenesis; however, as these cells undergo partial transformation into cancer cells, this vibration frequency gradually increases. Notably, the bistable effect is absent when

ωc = 4.90 MHz but emerges as

ωc rises to 5.325 MHz. In fact, a larger

ωc induces a broader bistable region. This observation indicates that monitoring the evolution of the bistable region offers a feasible approach to tracking cellular carcinogenesis.

To enhance the visualization of these results, we plot a bistability phase diagram for cancer cell detection in the system’s parameter subspace [

dc;

β;

N = 12; Δ

r = 2 nm;

λ = 5 GHz;

Ipu = 640 GHz

2] (

Figure 6b). In a strong exciton–phonon coupling regime, the bistable effect can be observed at point C (

dc(C) = 19.62 nm), where

β equals only 1.82%, suggesting that OB appears accordingly when 1.82% of normal cells are transformed into cancer cells. Furthermore, as the proportion of cancerous cells increases, the bistable region broadens progressively.

Figure 6c illustrates how the critical value

βc changes with SiO

2 shell thickness Δ

r, where

βc denotes the proportion of cancerous cells corresponding to the exact onset of OB. At Δ

r = 2 nm,

βc equals 1.82%. When Δ

r increases to 2.1 nm,

βc rises to nearly 100%, which demonstrates that

βc is highly sensitive to the SiO

2 shell thickness. This sensitivity can be attributed to the strengthened exciton–plasmon coupling induced by the adjustment of the dielectric shell thickness. In contrast, the relationship between

βc and the decay rate of the cell membrane

γc follows a starkly different pattern (

Figure 6d).

βc remains almost constant at 1.82% even as

γc varies, a behavior stemming from the negligible effect of the cell membrane’s decay rate on OB modulation. Furthermore, as the proportion of cancerous cells increases, the bistable region exhibits a progressively broadening trend. Collectively, these findings establish a highly accurate and practical approach for the early diagnosis of cancer cells. Complementarily, the distinct features of bistable signals enable the reverse deduction of cellular malignant transformation status, obviating the need for both biomarker labeling and broadband spectral scanning.

In contrast to conventional optical bistable devices, our SQD-MNS–cell membrane system offers three key advantages for cancer detection applications: (1) it enables label-free biosensing, where cell membrane biophysical parameters directly modulate bistable properties; (2) it supports low-power operation, as the synergistic effects of exciton–plasmon and exciton–phonon coupling efficiently lower switching thresholds; (3) it provides integrated diagnostic functionality, facilitating the simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analysis of cellular malignant transformation.

Based on our theoretical framework and the latest advances in nanophotonics and biomaterials, four core engineering and materials science barriers must be addressed to advance the practical translation of the proposed SQD-MNS–cell membrane hybrid system. (1) The scalable, reproducible fabrication of such heterostructures with uniform optical properties is hindered by random conjugation and non-specific binding in large-scale processes. These limitations contravene the model’s assumptions of precisely regulated SQD-MNS spatial coupling and SQD characteristics. A feasible solution lies in optimized surface functionalization via site-specific covalent linkers. This approach would not only enhance structural uniformity but also directly tailor the coating composition and surface morphology of the MNS. This precise structural modulation is critical because our findings demonstrate that it dictates the plasmonic response of the hybrid system and in turn its biosensing performance for early cancer diagnosis. (2) Retaining the structural and optical integrity of the hybrid system over extended periods in complex biological microenvironments is a prerequisite for clinical translation. Notably, the stability of the MNS coating, including its composition and morphological robustness, directly governs the persistence of OB which is the core sensing mechanism of the system. Future efforts to engineer durable, biocompatible MNS coatings will therefore be pivotal to bridging advanced coating science with real-world biomedical sensing applications. (3) High-affinity, target cell membrane-specific binding is required to eliminate off-target interference and ensure high signal-to-noise ratios. This goal is achievable through the rational design of surface-conjugated targeting ligands. When integrated with precisely engineered MNS coatings, such ligand-functionalized heterostructures can synergistically optimize both the specificity and sensitivity of the biosensing platform. This integration further reinforces the intrinsic link between coating design, plasmonic behavior, and biosensing efficacy. (4) Downsizing the laboratory-scale optical platforms currently used to quantify absorption peak variations and optical bistability is a key step toward deploying the system for point-of-care and intraoperative sensing applications. Miniaturized devices would need to retain the capability to resolve subtle changes in bistable behavior triggered by MNS coating modulation. This technical challenge underscores the need for cross-disciplinary collaboration between materials scientists specializing in advanced coatings, nanophotonics researchers, and clinical diagnosticians.

Collectively, these challenges and their proposed solutions highlight a central contribution of this work. We have established an explicit, mechanistic link between MNS coating composition, surface morphology-dependent plasmonic responses, and the biosensing performance of quantum-plasmonic–biological hybrid systems. By delineating this connection, our study not only advances the fundamental understanding of OB regulation in such complex systems but also forges a critical bridge between advanced coating science and cutting-edge biomedical sensing.