1. Introduction

Technical textiles are high-value products with expensive costs. They have superior performances due to their non-flammability and high strength with resistance against microorganisms, chemicals, and weather conditions. Applications of technical textiles are given in

Figure 1. Among technical textiles, automotive applications form the largest segment, accounting for about 20% of the market share [

1,

2]. These textiles not only serve functional purposes like insulation, safety, filtration, and decoration in vehicles but also significantly contribute to passenger comfort. The growing number of vehicles globally is expected to drive further demand for advanced textile solutions in this sector.

A variety of textile structures, such as woven, knitted, nonwoven, and composite materials, are used depending on the specific area within the vehicle. The distribution and usage of these materials in vehicles are documented in studies by Mukhopadhyay and Partridge [

3].

Textile fibers used in automotive seat covers play a crucial role in determining both the durability and cost of the final product. These fibers are generally classified as synthetic, natural, or high-performance and are used to develop woven, knitted, nonwoven, or composite textile structures [

4]. Automotive textiles are considered one of the most distinctive and rapidly growing segments within the field of technical textiles. Since safety and comfort are the primary expectations of vehicle users, selecting appropriate fibers that can meet these criteria is essential. Among synthetic fibers, polyester, polyamide (nylon), acrylic, and polypropylene are often preferred due to their superior mechanical strength, thermal resistance, dimensional stability, abrasion resistance, moisture repellency, and UV resistance compared to natural fibers [

4]. In particular, polyester dominates the market, accounting for approximately 90% of all fibers used in automotive applications, thanks to its high strength, UV and heat resistance, excellent shape retention, durability, and cost effectiveness [

5]. It also offers advantages such as easy care, high tear resistance, and wrinkle resistance; however, having a very low moisture absorption rate (approximately 0.4%) can negatively impact thermal comfort, especially in hot climates [

6]. Other fibers used in automotive textiles include nylon 6 and nylon 6.6, which are known for their exceptional strength, elasticity, hardness, and wear resistance. Nevertheless, their lower UV resistance compared to polyester makes them more vulnerable to degradation under prolonged sunlight exposure. Acrylic fibers offer lower abrasion resistance, limiting their usage, while wool, despite providing excellent comfort due to its high moisture absorption, is restricted to luxury vehicles because of its high cost. On the other hand, polypropylene is widely used in technical applications such as luggage compartments, seat backs, door panels, and small carpet areas, owing to its hydrophobic nature, low density (0.92 g/cm

3), and cost advantage. However, it is less commonly used in seat cover fabrics due to its low melting point, limited extensibility, and coloration challenges during fiber spinning [

3,

7,

8].

The comfort and performance of automotive seat cover fabrics are primarily influenced by the type of fabric and the yarn properties used. Yarns must offer high resistance to heat, friction, and wear, along with dimensional stability and easy maintenance. Over 70% of automotive textiles are produced from textured filament yarns, mainly air-textured and false-twist types, due to their superior durability [

9]. Among fabric types, woven, knitted, and nonwoven structures are commonly used. Woven fabrics, such as jacquard velour, provide strength but lack stretch, which can be compensated by adding stretch polymers [

6,

10]. In contrast, knitted fabrics offer better softness, drape, and elasticity, making them suitable for applications requiring flexibility. Transfer coating is preferred for knits to avoid excessive stiffness. Warp-knitted velour fabrics have advantages in design efficiency and reduced waste compared to circular knitted types. Although not yet widespread, spacer fabrics are promising alternatives to foams, offering better breathability and sustainability. Nonwoven fabrics, often used in car flooring, have lower strength and are typically coated with resins to improve durability and moldability [

10].

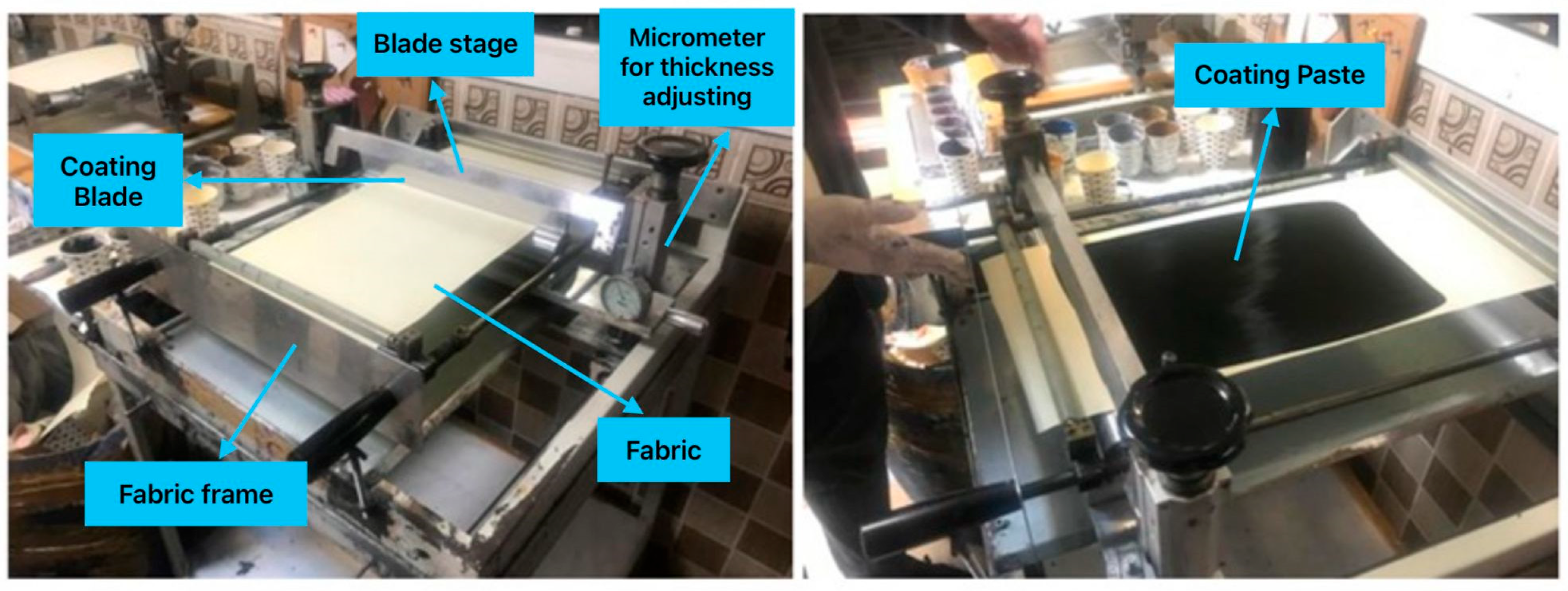

Coating is the process of applying chemical substances to one or both sides of woven, knitted, or nonwoven textile surfaces in order to improve their physical and aesthetic properties, expand their fields of application, and combine the advantages of fabrics, polymers, foams, and films [

11]. In the production of technical textiles, the coating material is generally applied as a viscous liquid spread over the substrate, which then cures and dries to form a film layer; in some cases, coatings undergo chemical crosslinking to form a solid film. For an effective coating, the fabric used is expected to have a clean, smooth, uniform surface, durability, dimensional stability, chemical resistance, and low cost [

12]. Coating agents mainly consist of thermoplastic polymers (such as PVC, polyurethane, natural, and synthetic rubbers), and since they are exposed to heat along with the fabric during coating, their thermal behavior must be known in advance [

13]. Adequate flow properties are essential for coating agents, which are provided by carrier media or other additives ensuring homogeneous distribution on the fabric. Solvent-based coatings evaporate quickly after application but are less preferred today due to environmental concerns and regulations; water-based coatings require energy-intensive drying systems, while hot-melt and powder coatings do not use solvents and instead melt at process temperature, enabling uniform application [

13]. The selection of coating materials depends on chemical, environmental, and mechanical requirements, as well as cost and processing properties [

14]. Adhesives are also used between substrate layers to ensure adhesion, and most formulations aim to improve abrasion resistance and durability [

13]. Compared to fabrics, film layers are less porous and more resistant to liquids and gases; however, as thickness increases, stiffness also rises, making it difficult to achieve the required balance of flexibility and rigidity solely with the film layer. Therefore, the performance of the final product is determined not only by the choice of fabric and coating material but also by the coating technique applied.

In case of PVC coating, the K value (Fikentscher K value) is an indicator for molecular weight and thus its chain length, degree of polymerization of the resin, and viscosity of PVC affect mechanical, rheological, and processing properties. If the K value is between 50 and 60, then it is called Low value and it has lower viscosity, easier processing, but weaker mechanical strength. If the K value is between 65 and 68, then it is called Medium and it has balanced processability and mechanical properties, and as a result it is the most applied type. If the K value is between 70 and 80+, then it is called High value and it has high molecular weight, and it results in higher tensile strength, toughness, and impact resistance but is more difficult to process due to higher viscosity [

15].

When the K value increases, tensile strength and hardness increase because the polymer chain gets longer and intermolecular interactions get stronger. Lower K value PVCs are more flexible and have higher elongation due to shorter chains and easier flow. However, optimum mechanical properties (balance between tensile strength and elongation) are often obtained by blending resins of different K values—for instance, a 50/50 mix of K66 and K74 produced good mechanical properties with no defects [

16].

Sya’bani et al. showed that artificial leather made from higher K value PVC (K = 74–76) exhibited greater tensile strength and elongation than lower K value PVCs (K = 66–68) [

16]. Similarly, Çoban et al. found that higher K values (K80–K90) led to improved strength, but too high of K values could reduce process uniformity and fusion during extrusion, resulting in slightly lower tensile strength if not optimized [

17].

Higher K value PVC has higher viscosity, and this higher viscosity makes it harder to process and homogenize. For solving this problem, mixing high and low K value PVCs can improve processability while retaining strength, and if the difference between K values of mixed PVCs is less than 10K units, then the performance of the PVC mix is better compared to higher K value differences because the higher differences bring the incompatibility and micro-defects [

16]. K values and their effects on properties are summarized in

Table 1.

Recent studies highlight the growing emphasis on sustainability, functionality, and advanced material performance in automotive textiles and coatings. Bio-based coatings such as Piñatex

®, AppleSkin™, Deserttex™, and Mylo™ have been shown to reduce CO

2 emissions by 60–80% and energy consumption by up to 45% compared to PVC and PU, although production costs remain about 30% higher [

18]. Metal-coated textiles, which combine fabric flexibility with metallic conductivity, thermal reflectivity, and electromagnetic shielding, have also gained significant attention. A recent review compared sputtering, CVD, and electroplating methods and highlighted the advantages of advanced ALD and PECVD techniques for achieving superior coating quality and environmental sustainability [

19]. Complementary research on conductive flocked fabrics for automotive interiors found that silver-coated (F-Ag) samples exhibited higher conductivity (~24 Ω/cm) and thermal stability (403 °C) than carbon black-coated (F-CB) ones (~390 Ω/cm), maintaining performance after 6000 abrasion cycles; a multitouch sensor prototype based on F-Ag further demonstrated strong potential for flexible electronic interfaces [

20]. In parallel, studies on antibacterial automotive textiles showed that UV exposure of 601 kJ/m

2 reduced antibacterial efficiency in PVC-based leather from 99% to 65% (

E. coli) and 98% to 60% (

S. aureus) while decreasing hydrophobicity from 84° to 62° [

21]. Collectively, these studies reveal two main directions in current research: the advancement of eco-friendly materials through bio-based coatings and the enhancement of functional durability and electronic performance through metal-coated and conductive textile technologies in next-generation automotive interiors.

NaSS is a functional additive widely used in the textile industry as a dyeing auxiliary. It facilitates the dispersion of water-insoluble pigments and vat dyes, ensuring homogeneous coloration, while enhancing fiber affinity to promote stronger dye fixation and produce vibrant, durable shades. Acting as a leveling agent, it prevents shade irregularities across the fabric surface, and through its chelating ability, it sequesters metal ions in the dye bath that could otherwise cause undesirable color variations. NaSS also stabilizes the dye bath by preventing precipitation in high-electrolyte environments and serves as a reductive clearing agent in vat and sulfur dyeing processes, removing unfixed dye residues to improve colorfastness. Through these multifunctional roles, NaSS plays a critical part in achieving high-quality, long-lasting, and evenly dyed and coated textiles.

This study aimed to develop a multi-purpose coated knitted automotive seat cover that could meet the expectations of the automotive industry and serve as an alternative to currently used products. Six fabrics with different knitting types were produced, and three different four-layer coating recipes were applied to these fabrics, resulting in a total of 30 samples. All produced fabrics were tested according to automotive standards, the materials and methods used were explained, and the effects of changes in the coating recipes on the performance properties were observed. This study focuses on effective properties on final coated products in terms of processability of the coated textile in production of automotive seat covers as well as its potential interaction with other textiles during use.

3. Results and Discussions

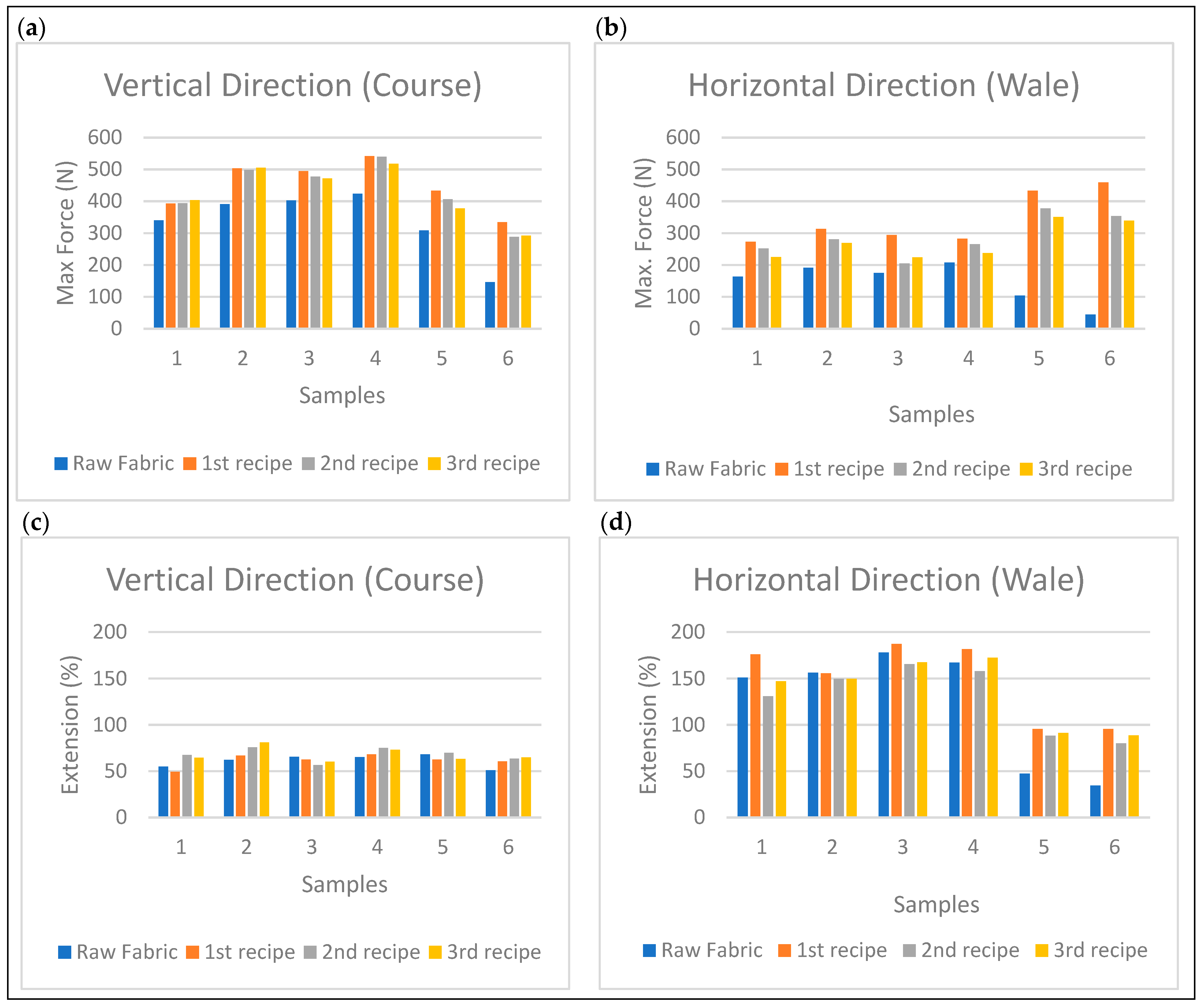

All samples were tested for tensile strength both for vertical direction (course) and horizontal direction (wale). Bonding strength tests were applied onto the samples that have coating to observe the separation performance of coating. Abrasion and rubbing tests were performed to observe the wear performances while perspiration and light fastness tests were performed to observe daily usage performances. In sample naming in results for all tests, the first number before the dot represents the number of fabric sample, while second number after the dot represents the number of recipes that is applied onto the related fabric. For example, 1.1 is Sample 1 fabric that is treated with Recipe 1. While 2.1 is Sample 2 fabric that is treated with Recipe 1.

3.1. Tensile Strength Test

Tensile test was performed according to EN ISO 13934-1:2013 for fabrics that have 50 mm ± 0.5 mm × 200 mm dimensions with a Titan 2 tensile tester. The results of the tensile tests applied to the fabrics coated with different recipes are given in

Table 5.

Generally, after coating with all recipes, tensile strength increased compared to the raw versions of the fabrics as expected.

As the k value increases, the strength is expected to increase as the molecular chain will lengthen. However, when the test results were examined, it was seen that the strength values of the samples coated with PVC with 70k value were higher than the strength values of the samples coated with PVC with 80k value. The average breaking strength of the samples coated with the first coating recipe is 492,677 N in the course direction and 314.5 N in the wale direction. The average tensile strength of the samples coated with the second recipe is 475,495 N in the course direction and 255,639 N in the wale direction. The average strength of the fabrics coated with the third recipe is 482,669 N in the course direction and 255,934 N in the wale direction. The best results were yielded with first recipe with 70k PVC for all samples in the case of max force of both the vertical and horizontal direction.

The fabric shows a certain elongation until the breaking point. Wale direction elongations were higher than course direction elongations as expected due to natural geometry of the knitting structure with higher extensibility in wale direction. Also, process direction of coating affects the elongation because it covers the fabric structure from course direction and provides rigidity compared to other direction. During the elongation in the samples to which the first and second recipes were applied, it was seen that the average elongation in the course direction of the samples coated with the first recipe with 70k value was 60.017%, the samples coated with the second recipe with 80k value was 65.485%, and the fabrics coated with the third recipe is 65.396% on average, while the elongation rate in the wale direction is 164.98% for the first recipe, 146.263% for the second recipe, and 140.279% on average for the third recipe. It has been observed that the elongation of the fabrics coated with the first recipe is less than the elongation rate in the course direction of the fabrics coated with the second and third recipe, but all are higher when compared with the elongation rates in the course direction. However, the elongation values of all samples in same direction were very close to each other, and it does not provide a statistically meaningful difference to select a best recipe depending on elongation behavior (

p >> 0.05), but samples had suitable elongation values for automobile textiles. If we need to select a recipe, the first recipe can be a better alternative for almost all tensile performances (see

Figure 3 for vertical and horizontal strength performances).

Also, it is observed that NaSS usage in pretreatment improves the tensile strength, but NaSS amounts higher than two g/L in recipe decrease the tensile strength, probably due to higher interaction with polyelectrolyte molecules [

22].

Fabric structure was shown to affect results, as two-thread single jersey samples had higher horizontal max force and lower horizontal extension because the structure is tight. In the case of performance in the vertical direction, both fabric structure and application direction of coating had no statistically meaningful difference, i.e., yarn count, fabric unit weight, machine diameter, and needle density did not provide statistically meaningful differences (p >> 0.05).

Considering tensile test results, the best results can be yielded with Recipe 1, NaSS amount 2 g/L and two-thread single jersey fabric structure.

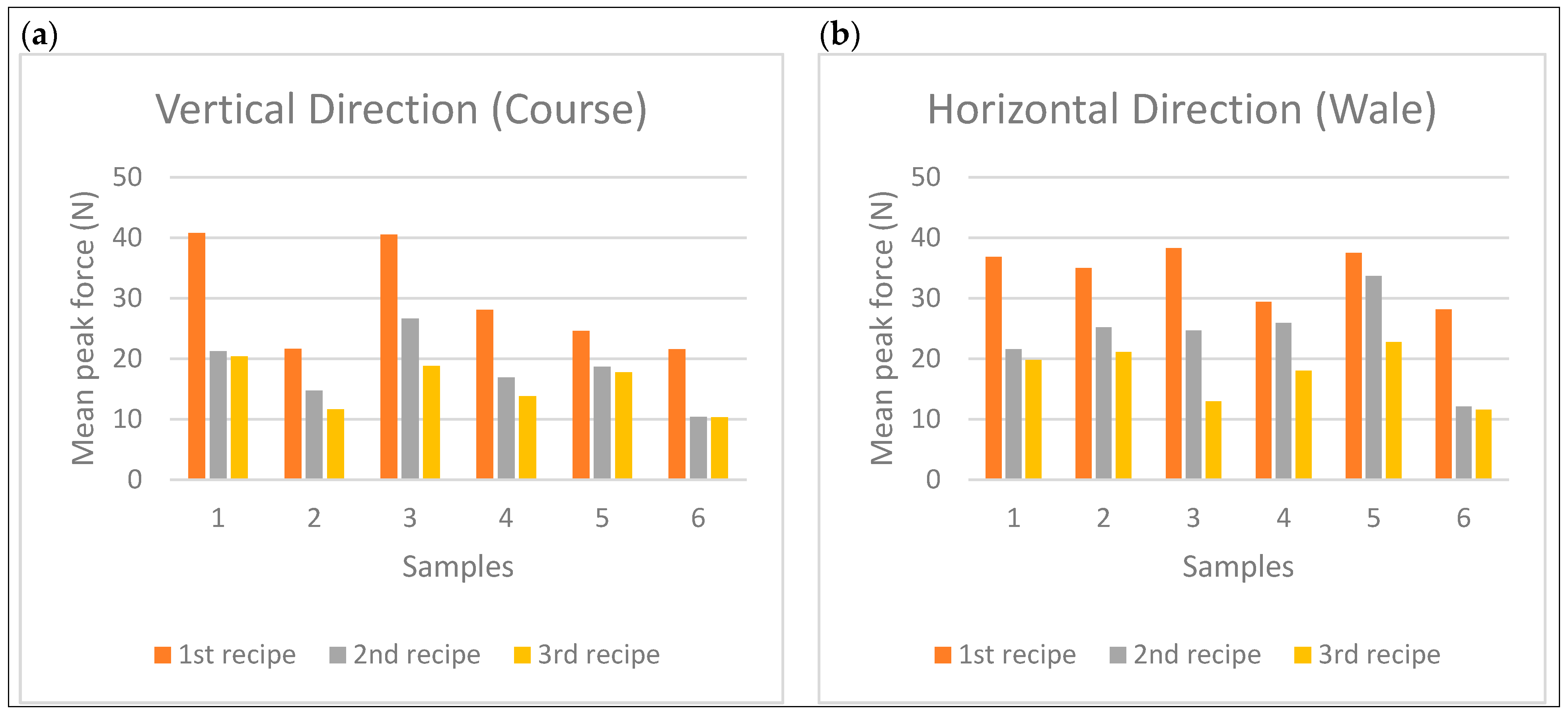

3.2. Bonding Strength Test

Bonding strength test was performed according to EN ISO 2411:2024 for fabrics that have 50 mm ± 0.5 mm × 200 mm dimensions. The 100 mm portion is manually separated from the surface fabric, and remaining coating is separated with a Titan 2 tensile tester. The results are given in

Table 6 and

Figure 4.

The coating recipe and coating materials used for this study are the main factors affecting the bond strength. When the values of bonding strength in course and wale direction depending on the change in PVC’s K value are examined in the table, it can be said that the first recipe has higher bonding strength values than the second recipe.

When the change in bonding strength in the direction of the wale and course due to the change in the amount of calcite is examined, it can be said that the fabrics coated with the first recipe have higher bonding strength values. As a result, when the three recipes are compared, it can be concluded that the fabrics coated with the first recipe give the best results in terms of bonding strength.

Also, it is observed that NaSS usage in pretreatment improves the bonding strength but amounts higher than two g/L in recipe decrease the bondingstrength, probably due to higher interaction with polyelectrolyte molecules [

22].

Fabric structure was shown to have affected test results, as two-thread single jersey samples had a higher horizontal max force and lower horizontal extension because the structure is tight. In the case of performance in the vertical direction, there were no statistically meaningful differences due to both the fabric structure and application direction of coating as vertical. However, yarn count, GSM, inch, and fineness did not provide statistically meaningful differences. (p >> 0.05).

Considering tensile test results, the best results can be yielded with Recipe 1, NaSS amount 2 g/L and two-thread single jersey fabric structure.

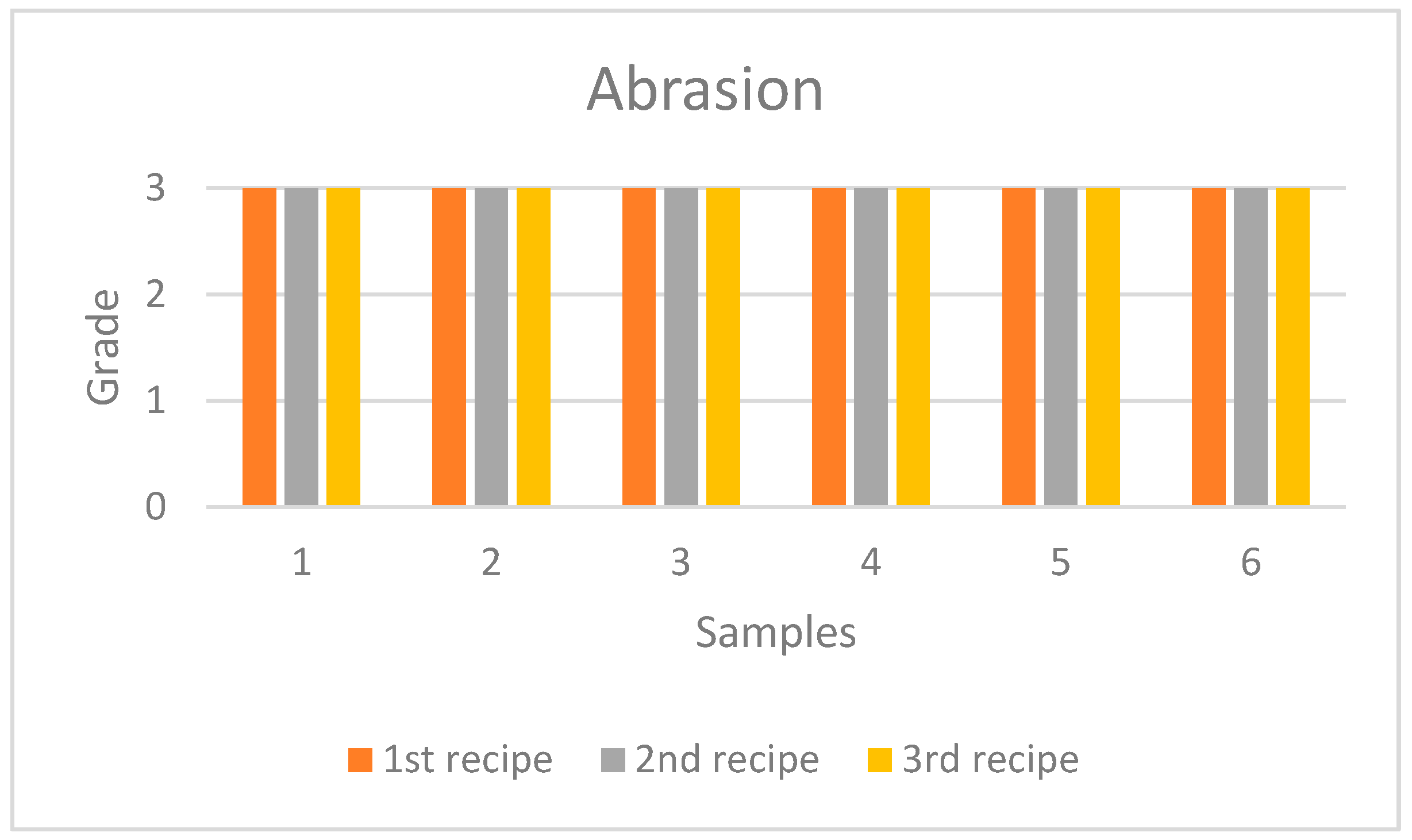

3.3. Results of Abrasion Tests

An abrasion test was performed according to EN ISO 12947-4:1998 with 100,000 rubs and 12 kPa weight. In the interpretation of the Martindale abrasion test results, the whitening of the fabrics due to abrasion is graded. The degree of whitening is scored between 1 and 3 by comparing with the references on the gray scale. Acceptance criteria differ according to automotive main industry manufacturers. According to the VW 50105 specification of the Volkswagen company, which was taken as a reference within the scope of this study, fabrics must achieve at least 2 points in order to be accepted. All of the examined fabrics successfully passed the abrasion tests by achieving 3 points as given in

Figure 5.

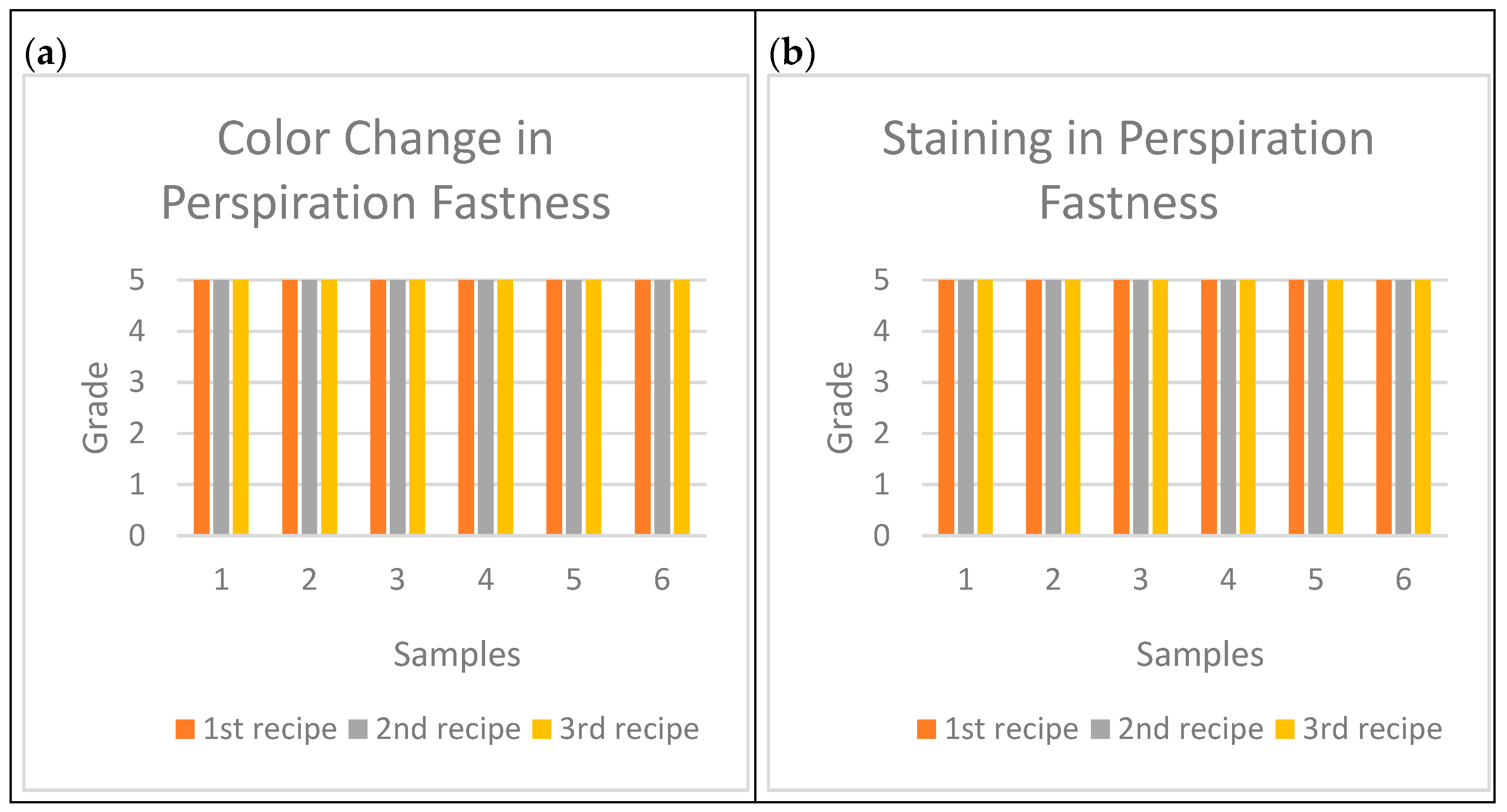

3.4. Results of Colorfastness to Rubbing

Rubbing test was performed according to EN ISO 105-X12:2016. For the test, four fabric samples (two course and two wale directions) measuring 140 × 50 mm are prepared, along with four 50 × 50 mm accompanying cloths. The test is performed in two stages: dry and wet rubbing. In the dry friction test, the dry cloth attached to the friction foot is rubbed back and forth ten times within ten seconds on a 100 mm line of the sample using a 9 N downward force. The wet rubbing fastness test follows the same procedure, except the accompanying cloth is moistened to its own weight before testing. It was observed that no color change occurred in the samples in both dry and wet rubbing fastness tests. In addition, it was observed that no color staining occurred in the accompanying cloth. As a result, when the samples coated with three different recipes were evaluated with gray scale, all samples were evaluated with the best value of 5 in terms of coloring and staining as given in

Figure 6.

3.5. Results of Colorfastness to Perspiration Test

The color fastness test against perspiration was performed according to EN ISO 105-E04:2013 for both basic and acidic solutions. Two fabric samples measuring 100 × 40 mm are sewn together with a multifiber fabric of the same size and tested using a perspirometer—a device with a steel base and acrylic plates that applies a 12.5 kPa (5 kg) load to the samples. Separate acidic and basic perspiration solutions are prepared. The combined fabric sample is first immersed in a basic solution (pH 8) at a 1:50 ratio for 30 min at room temperature until fully wetted. It is then placed between the acrylic plates, compressed, and kept in an oven at 37 ± 2 °C for 4 h. The same procedure is repeated using the acidic solution. After both tests, the samples are dried separately to prevent contact, and finally, the degree of color change (fading) in the main fabric and staining on the multifiber fabric are evaluated. After looking at each sample in the light box, it was observed that there was no color change on the coated fabric, and there was no staining on the accompanying fabric. When these samples are evaluated by comparing with standard contrasts on the gray scale, they are at the 5th grade, which is the best value for both staining and color change as given in

Figure 7. This value is in the acceptable range for the coated fabrics within the scope of the study.

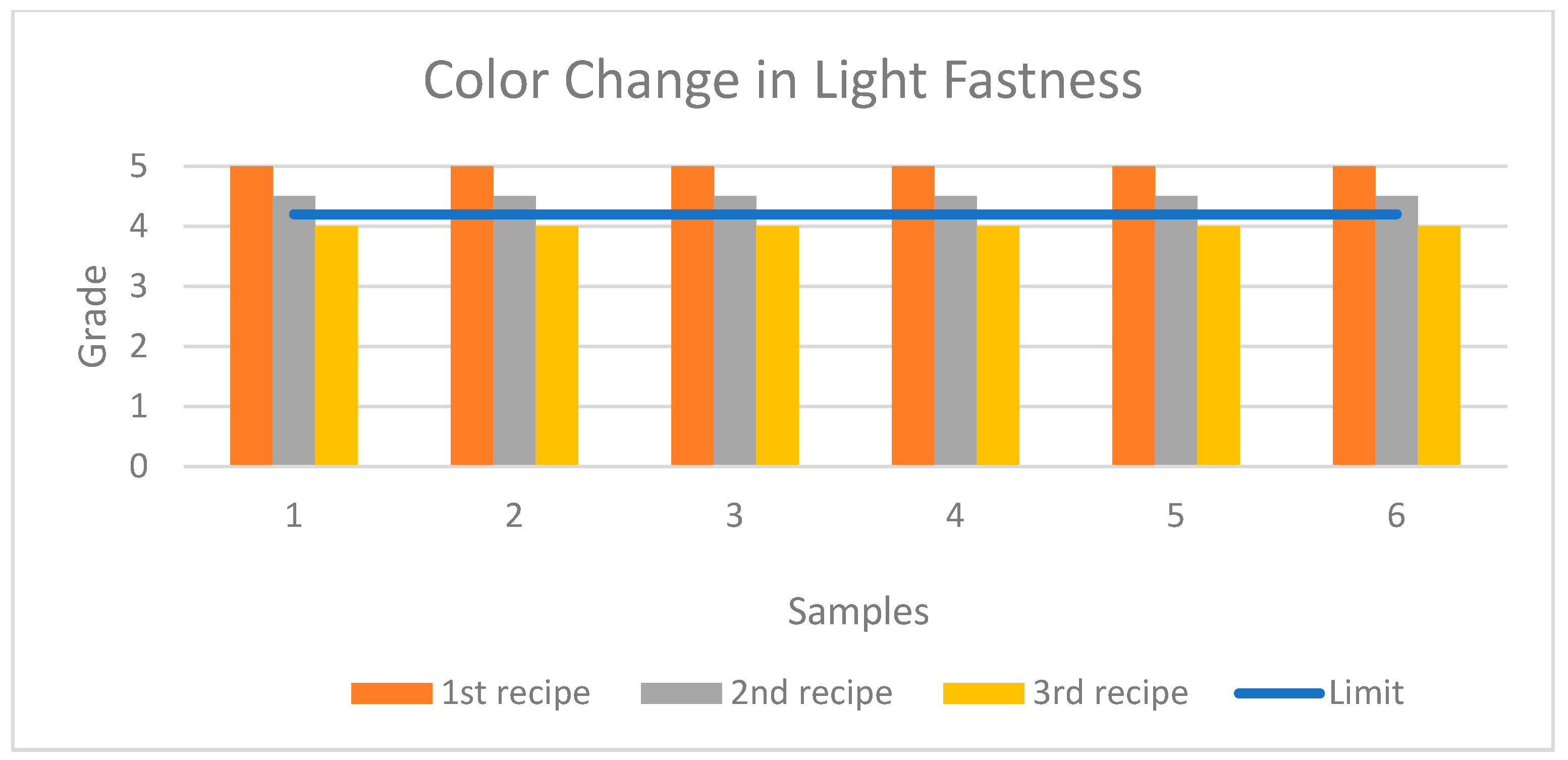

3.6. Results of Colorfastness to Light

The sample fabrics, for which light fastness was measured, were tested in accordance with the EN ISO 105-B02:2014 standard, under a Xenon light source, using the Xenotest Alpha+, Atlas Material (supplied from Etki Materyal Test Çözümleri, Istanbul, Türkiye). Sample fabrics prepared in 50 × 100 mm dimensions are evaluated in a light fastness testing device using a wool blue scale. During the test, the amount of fading in the fabrics is compared using the gray scale, while the fading degree of the samples whose light fastness is being measured is compared using the blue scale. The blue scale is rated between 1 and 8, and the gray scale between 1 and 5. The gray scale consists of five pairs of gray fabrics or cardboards, each representing a specific color difference. The blue scale, on the other hand, contains eight wool fabrics, each approximately twice as resistant to fading as the previous one. At the end of the test, the fading degree of the sample fabric is determined by comparing it with the reference wool samples on the blue scale. All evaluations are performed under standard D65 daylight conditions in a light cabinet.

Recipe 1 and 2 are acceptable for automobile textiles, while Recipe 3 is not sufficient for samples that face the light as much as automobile textiles. Also, it was seen that the light fastness test results of the fabrics created with yarn structures with different yarn counts and different knitting structures were the same. Based on these results, it can be said that knit structure and yarn count do not have a significant effect on light fastness. In addition, looking at the results of these tests and the results of the studies in the literature, it can be said that the factor affecting the light fastness is the dyestuff used. The evaluation results of the fabrics are shown in

Table 7 and

Figure 8.

Considering light fastness test results, the best results can be yielded with Recipe 1.