3.1. Microstructure

ERNiFeCr-1 was deposited on L415QS pipeline steel by the CMT process to obtain a geometrically uniform single-layer multi-pass overlay, as shown in

Figure 1. The individual bead thickness is approximately 3.8 mm, with a bead width of about 5.2 mm. The cross-section is dense, and no lack of fusion or macro-cracks is observed, as shown in

Figure 1a–c. From the fusion line to the surface, the microstructure exhibits a continuous transition from epitaxial columnar grains to cellular–dendritic grains and locally fine equiaxed grains. Near the fusion line, grains grow preferentially along the heat flow direction, showing a typical epitaxial columnar/cellular–columnar morphology (

Figure 1d). In the middle region of the layer, the reduced thermal gradient and enhanced constitutional supercooling promote cellular–dendritic growth, with fine secondary phases and a few pores observed between dendrites, as shown in

Figure 1e. In the multi-pass overlap zones, banded remelting/re-solidification features appear, indicating secondary refinement and orientation adjustment induced by inter-pass thermal cycling. Overall, sound metallurgical bonding is achieved, and only a narrow dilution zone is formed at the interface, as shown in

Figure 1f.

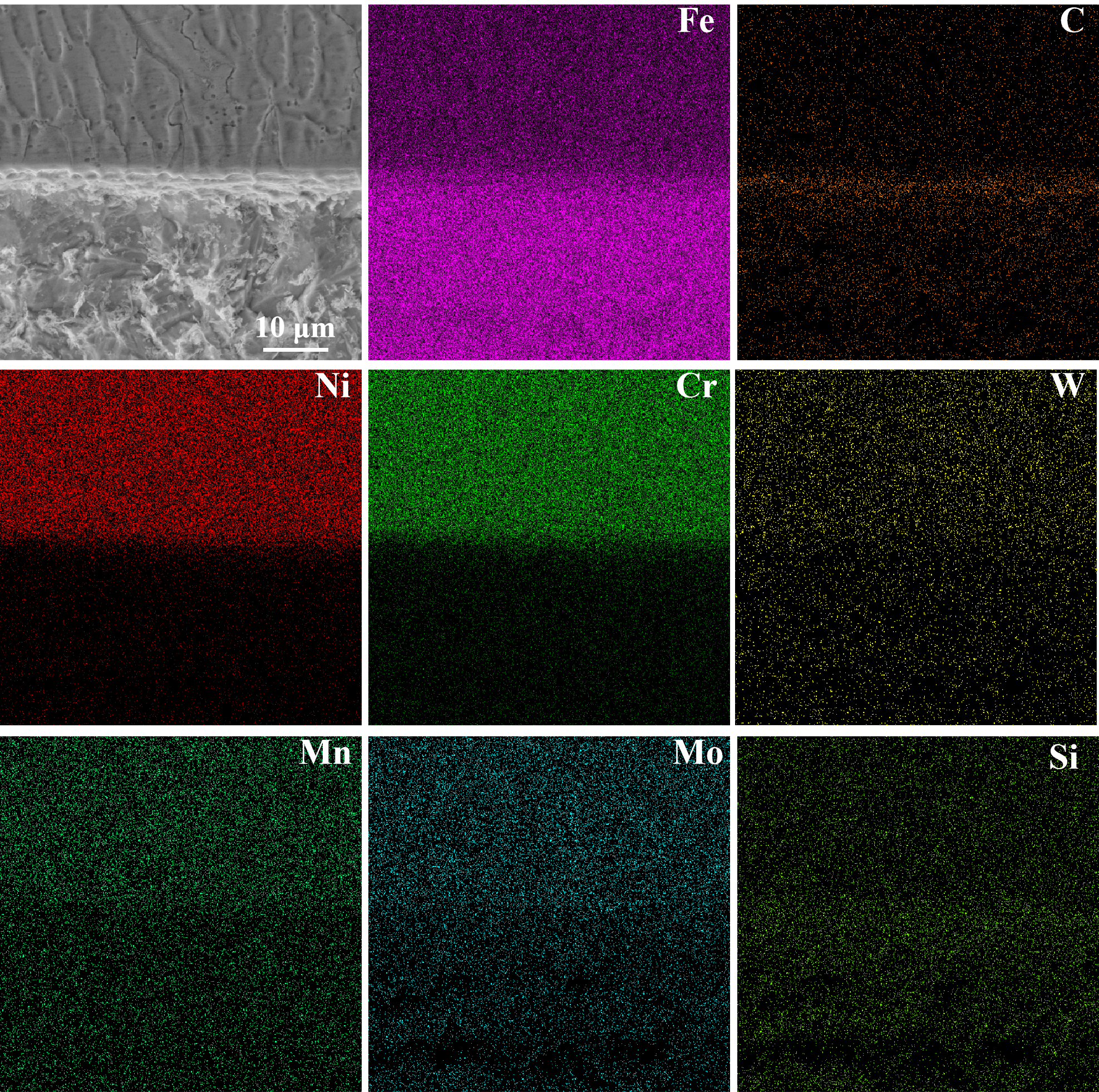

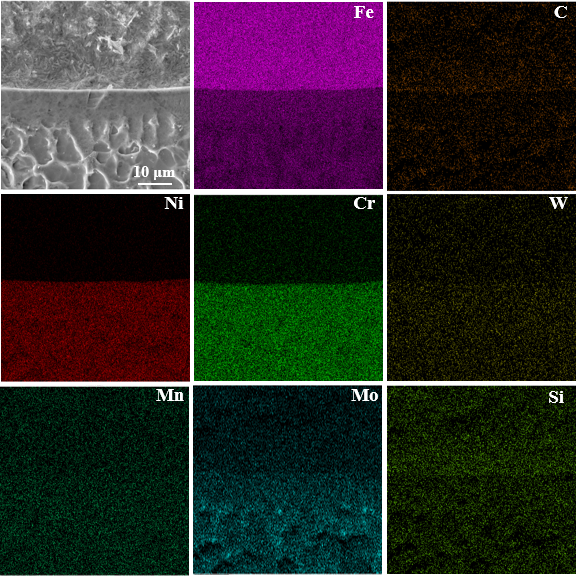

The elemental distribution across the substrate/coating interface is shown in

Figure 2. Fe exhibits the highest intensity on the substrate side and gradually decreases across the fusion line into the overlay. Ni and Cr are significantly enriched within the overlay and decrease toward the substrate, while Mn and Si are nearly uniformly distributed in the coating. Refractory elements W and Mo appear as weak but homogeneous background signals, indicating their segregation into interdendritic regions during solidification. C shows localized band-like enrichment near the fusion line and along interdendritic areas, in accordance with secondary phases, implying the preferential formation of local carbides. No pronounced spike-like segregation of a single element or continuous brittle interlayer is observed, confirming that the low heat input of the CMT process promotes stable chemical dilution and sound metallurgical bonding.

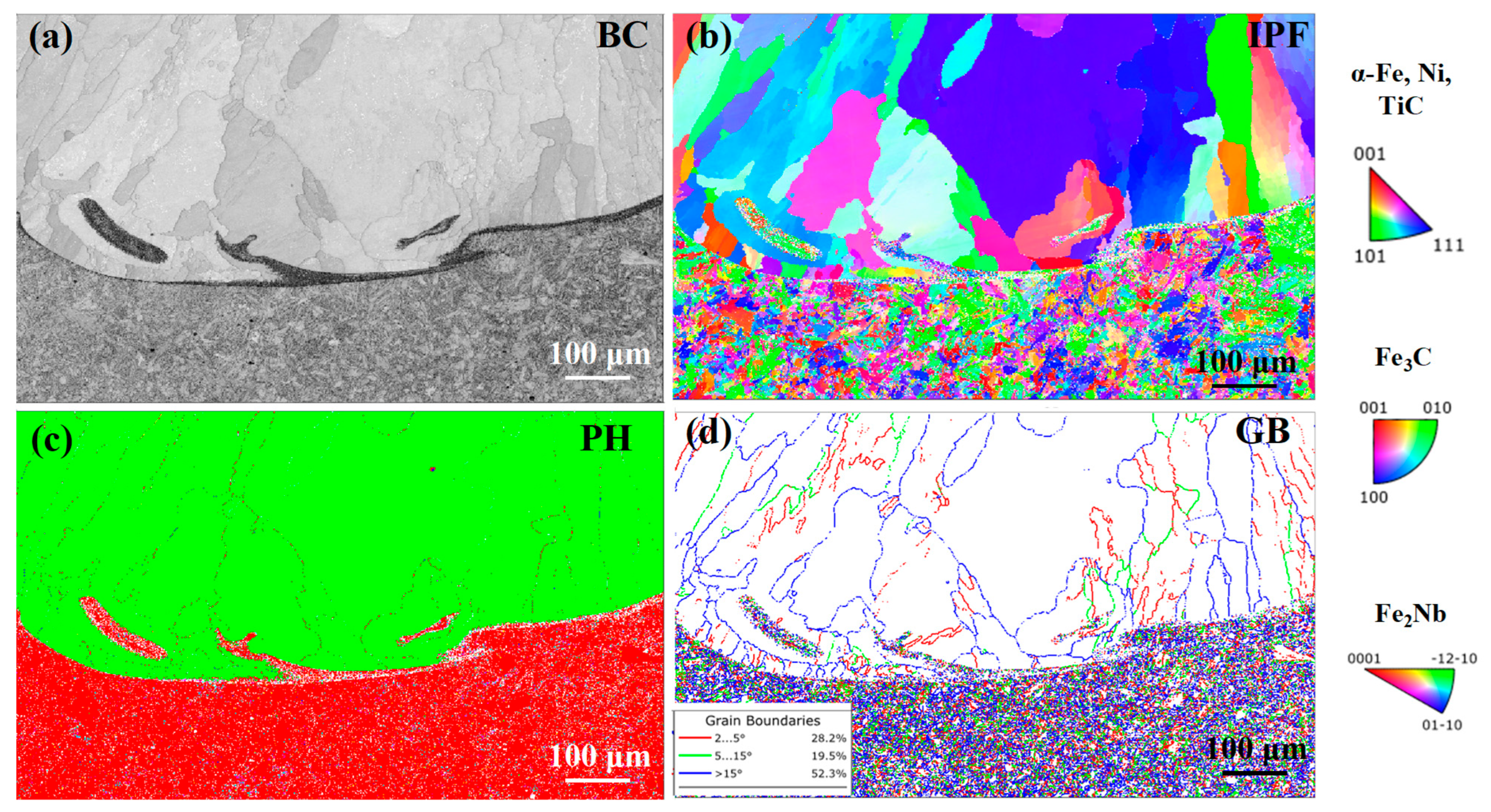

The EBSD results of the interfacial region are shown in

Figure 3. The band-contrast and orientation maps indicate that grains in the overlay near the interface grow epitaxially along the build normal, forming a pronounced texture, whereas grains in the heat-affected zone (HAZ) of the substrate are refined with dispersed orientations, as shown in

Figure 3a. The phase distribution map in

Figure 3c shows that the overlay is mainly composed of fcc Ni, while the substrate and HAZ consist of bcc α-Fe. Small amounts of Fe

3C and Fe

2Nb are detected along the fusion line and in interdendritic regions. Their volume fractions are listed in

Table 2, and these phases appear predominantly as fine granular or short stripe-like particles. Grain boundary statistics, as shown in

Figure 3d reveal that high-angle grain boundaries (HAGBs, >15°) account for approximately 52.3%, while low- and medium-angle boundaries represent about 47.7%. The relatively high HAGB fraction is beneficial for crack blunting and toughness enhancement of the overlay and is attributed to grain refinement induced by multi-pass overlap and the associated remelting-recrystallization process.

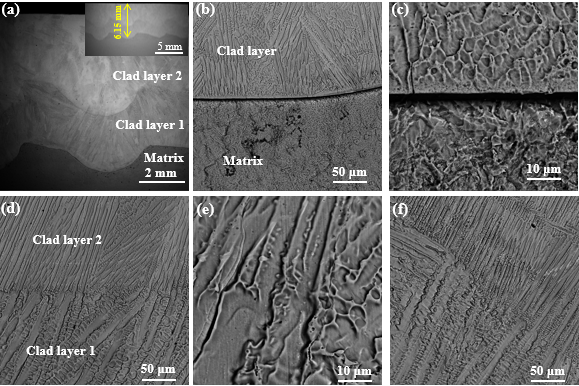

Using the same CMT parameters, a geometrically uniform double-layer multi-pass ERNiFeCr-1 overlay was deposited on the L415QS substrate, as shown in

Figure 4a. Macroscopically, the first (Clad layer 1) and second layer (Clad layer 2) exhibit clear boundaries without lack-of-fusion defects. The total thickness is approximately 5.0–5.5 mm, and the bead width of the second layer is about 6.15 mm. Compared with the single-layer overlay, the double-layer configuration shows a fuller surface profile and more pronounced remelting bands in the overlap regions, indicating a stronger interpass thermal cycle. Near the fusion line between the substrate and the first layer, grains grow epitaxially along the heat flow direction, forming columnar to cellular–columnar structures, as shown in

Figure 4b,c. In the middle of the first layer, the microstructure transforms into cellular–dendritic morphology. At the interface between the first and second layers, as shown in

Figure 4d–f, a continuous and dense remelted band is observed, with sound metallurgical bonding. The dendrite arm spacing in the second layer is clearly smaller than that in the first layer, and fine equiaxed grain islands appear near the interface. This is attributed to the heat flow directed into Clad layer 1 during deposition of the second layer, which promotes grain coarsening in the underlying layer while refining the newly solidified upper layer. Overall, the upper columnar grains in the double-layer coating exhibit a higher aspect ratio and stronger preferred orientation than those in the single-layer coating.

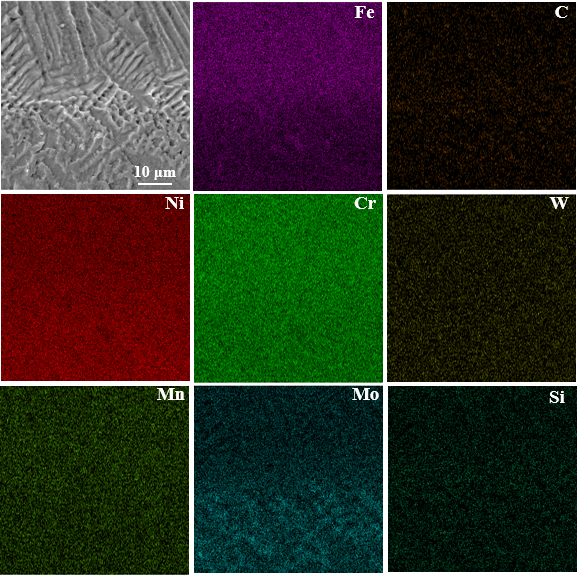

Elemental mapping of the region between Clad layer 1 and Clad layer 2 is shown in

Figure 5. Fe, Ni, Cr, Mn, Si, W, and Mo display an approximately uniform distribution across the interlayer region, without continuous enrichment or depletion bands. This is consistent with the graded “Fe-decreasing into the overlay/Ni,Cr-decreasing toward the substrate” behavior observed at the substrate/coating interface in the single-layer specimen, and indicates that the second layer induces sufficient remelting and mixing of the upper part of the first layer, eliminating potential compositional jumps. Carbon shows only slight interdendritic enrichment, and no continuous carbide layer is detected, which reduces the risk of brittle interlayer formation. In general, the chemical homogeneity at the interlayer interface in the double-layer coating is superior to the graded transition at the substrate/coating interface of the single-layer coating, which is beneficial for interlayer strength and resistance to cracking.

EBSD analysis of the substrate/Clad layer 1 interface, as shown in

Figure 6a–d shows pronounced epitaxial growth and strong texture in the first layer near the fusion line. The substrate is mainly α-Fe (bcc), whereas Clad layer 1 is dominated by fcc Ni. Discrete Fe

3C and Fe

2Nb particles, together with minor Fe

2Mo/Cr

7C

3, are observed along the fusion line and interdendritic regions, mostly as granular or fine stripe-like phases decorating interdendritic areas or local interfaces. In the interfacial region between Clad layer 1 and Clad layer 2, as shown in

Figure 6e–h, large columnar grains with competitive growth appear on both sides of the curved remelted band, indicating enhanced preferential growth of the second layer under relatively higher heat input and lower thermal gradient. The phase constitution remains as an fcc-Ni matrix with a small fraction of interdendritic carbides/intermetallics, and no continuous brittle layer is observed. Grain boundary misorientation maps show that HAGBs (>15°) form a dense network within the recrystallized refinement band at the interlayer region, while they are relatively sparse inside the upper columnar grains. Compared with the single-layer coating (HAGBs ≈ 52%), the double-layer coating exhibits a slightly higher HAGB fraction within the refined interlayer band and a slightly lower fraction in the coarse columnar zone, reflecting a cooperative “crack-arresting refined band and load-bearing columnar region” behavior.

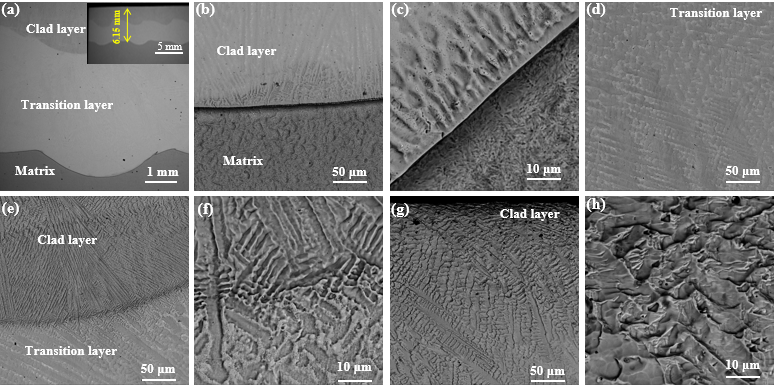

ERNiCrMo-3 was first deposited as a transition layer on L415QS pipeline steel, followed by an ERNiFeCr-1 overlay, forming a three-layer “substrate/interlayer/overlay” structure, as shown in

Figure 7a. As shown in

Figure 7b,c, the substrate/interlayer interface exhibits epitaxial columnar to cellular–columnar growth along the heat flow direction, with a dense fusion line and no lack-of-fusion or cracking. Within the interlayer, as shown in

Figure 7d, the grains are finer and the orientations are more uniformly distributed than in the single-layer coating. At the interlayer/overlay interface, as shown in

Figure 7e,f, a continuous remelted band is observed. Above this band, the ERNiFeCr-1 layer is dominated by cellular–dendritic grains with locally distributed equiaxed grains as shown in

Figure 7g,h. Compared with the double-layer same-alloy configuration (ERNiFeCr-1/ERNiFeCr-1), the upper columnar grains show a slightly lower aspect ratio and weaker preferred orientation, and the interlayer refinement band is more pronounced. This indicates that the transition layer effectively modifies the G/R ratio and solute undercooling conditions in the upper layer and suppresses excessive competitive columnar growth.

The elemental distributions at the substrate/interlayer and interlayer/overlay interfaces are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. From the substrate to the interlayer, Fe decreases smoothly, while Ni and Cr gradually increase; Mo is clearly enriched on the interlayer side, consistent with the high-Mo composition of ERNiCrMo-3. C, Mn, Si, W show no continuous enrichment bands and only slight fluctuations in interdendritic regions, as shown in

Figure 8. Compared with the steep chemical gradient at the substrate/coating interface in the single-layer specimen, the introduction of the interlayer redistributes the gradient into a controlled “substrate ↔ interlayer” region, thereby reducing the stress concentration and embrittlement risk associated with directly depositing a Ni-based coating on steel. From the interlayer to the overlay, as shown in

Figure 9, the overall distribution remains uniform. Ni and Cr are maintained at high levels in both layers, Mo decreases from the interlayer into the ERNiFeCr-1 overlay which is a low-Mo system, and Fe increases mildly, without spike-like enrichment or continuous depletion bands. Relative to the “double-layer same-alloy” coating, this system achieves comparable interlayer chemical homogeneity while introducing a beneficial Mo gradient, which enhances resistance to localized corrosion.

The EBSD results are shown in

Figure 10. At the substrate/interlayer interface, as shown in

Figure 10a–d, pronounced epitaxial columnar growth and strong texture are observed in the interlayer adjacent to the fusion line, while the heat-affected zone in the substrate is refined with dispersed orientations. Phase maps confirm α-Fe with a bcc structure in the substrate and fcc Ni in the interlayer. Within the interlayer, as shown in

Figure 10e–h, clusters of columnar and lath-like grains intersect, and a high density of high-angle grain boundaries (HAGBs) is present, indicating that the combination of low heat input and high alloy content promotes recrystallization and orientation redistribution, which is beneficial for crack path deflection. At the interlayer/overlay interface, as shown in

Figure 10i–l, fan-shaped competitive columnar grains form on both sides of the curved remelted band, but their size and texture intensity are weaker than those of the upper columnar zone in the “double-layer same-alloy” coating, demonstrating a “softening” effect of the transition layer on the solidification conditions of the overlay. Both the interlayer and overlay are mainly composed of fcc Ni, with a small amount of discrete granular or fine stripe-like second phases (Fe

2Nb, Fe

2Mo, Cr

7C

3, Fe

3C, etc.) distributed in interdendritic regions. No continuous brittle networks are observed. Compared with the single-layer direct Ni-based deposition, these phases are more discretely dispersed; compared with the double-layer same-alloy coating, Mo-containing precipitates are more concentrated in the interlayer and significantly reduced in the overlay, consistent with the designed elemental gradient.

In summary, the ERNiCrMo-3 interlayer combined with the ERNiFeCr-1 overlay produces a multiscale hierarchical structure characterized by epitaxial refinement at the substrate, chemical buffering in the interlayer, interfacial remelting-induced refinement, and moderated competitive growth in the overlay. The beads exhibit regular geometry (single-pass width ~6.15 mm) and dense metallurgical bonding. Chemically, a controlled Fe-decreasing and Ni/Cr-increasing gradient with Mo enrichment confined to the interlayer effectively suppresses local embrittlement. Microstructurally, the system is dominated by an fcc-Ni matrix with dispersed carbides/intermetallics, without continuous brittle networks. Compared with single-layer direct Ni-based deposition, this design alleviates the interfacial compositional jump and excessive columnar growth; compared with the double-layer same-alloy configuration, it maintains similar interlayer homogeneity while optimizing the corrosion and cracking resistance through tailored Mo partitioning. This provides a clear processing route for tuning texture and grain boundary networks via coupled “interlayer alloying + interpass thermal control.”

To further clarify the solidification characteristics of the three architectures, the EBSD grain boundary data and etched cross-sectional micrographs were quantitatively analyzed. The area fraction of high-angle grain boundaries (HAGBs, misorientation > 15°) was obtained from EBSD boundary maps, and the secondary dendritic arm spacing (SDAS) was measured on longitudinal sections by the linear-intercept method. For each coating, three characteristic regions along the build direction were considered: (i) the fusion-line/HAZ region adjacent to the L415QS substrate, (ii) the interfacial refined or remelted band, and (iii) the near-surface functional region that directly participates in sliding wear. In the single-layer ERNiFeCr-1 overlay, the HAGB fraction increases from approximately 47.5% at the fusion line to 53.2% in the near-surface cellular–dendritic zone, while the SDAS decreases, reflecting progressive refinement during multi-pass solidification. In the double-layer same-alloy coating, the remelted interlayer band exhibits a relatively high HAGB fraction of around 62.4% and a fine SDAS, whereas the upper columnar zone of Clad layer 2 shows a lower HAGB fraction and a coarser SDAS, which is consistent with its strong texture and pronounced interdendritic segregation. For the ERNiCrMo-3 interlayer + ERNiFeCr-1 overlay, both the interlayer refinement zone and the overlay surface show comparatively high HAGB fractions (≈68.2%) together with the smallest SDAS values among the three designs, indicating a dense HAGB network combined with refined dendrite arms that is expected to facilitate crack deflection and homogenize plastic deformation during sliding.

3.2. Friction-Wear Behavior

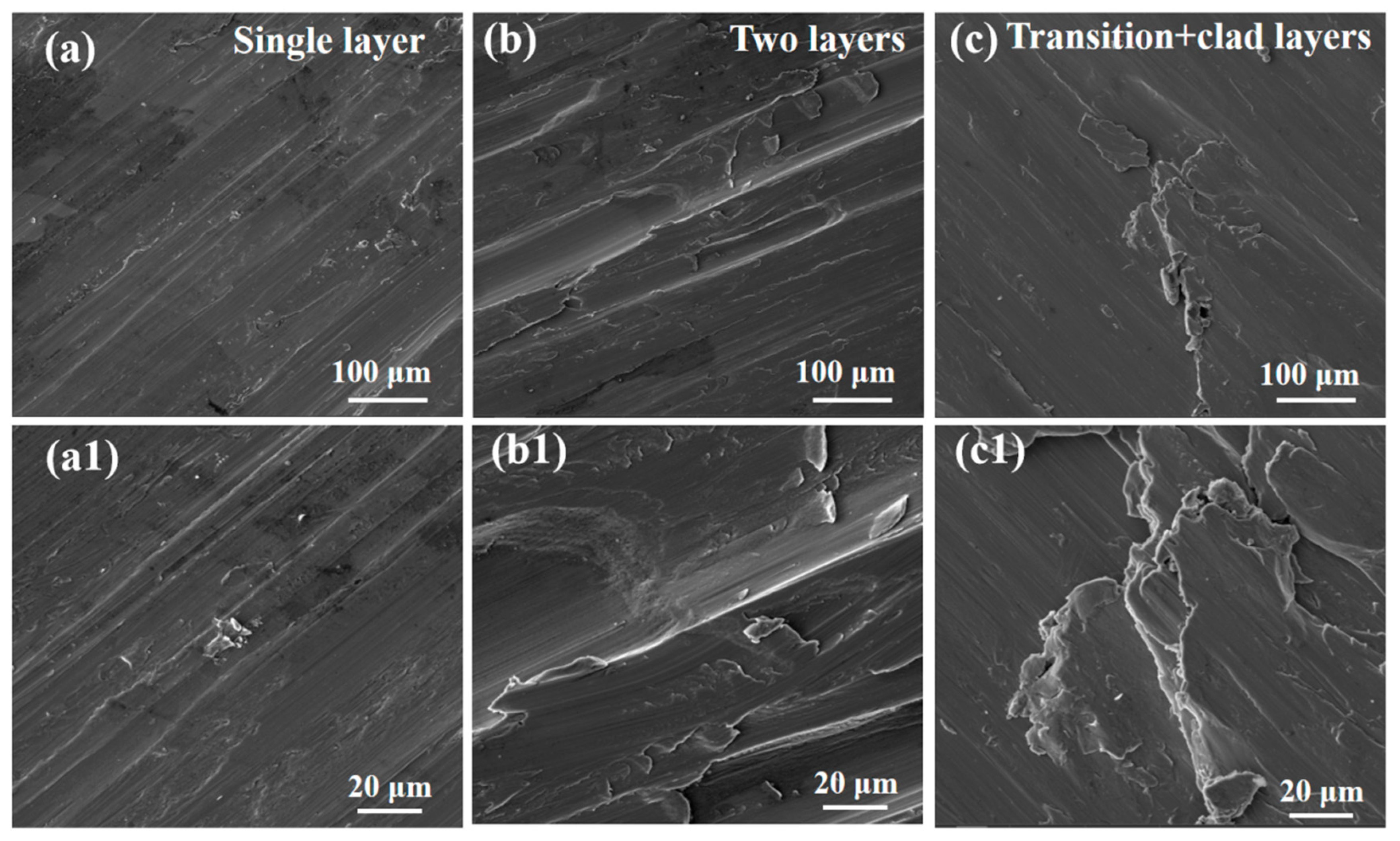

The evolution of friction coefficient as a function of time for the three coatings is shown in

Figure 11. Sample 3 (interlayer + overlay) exhibits the lowest and most stable friction coefficient in the initial stage, with values consistently lower than those of Samples 1 and 2. A slight decrease and plateau appear in the intermediate stage, followed by a marked increase and pronounced fluctuations after approximately 10

3·s. Sample 1 (single-layer overlay) maintains an intermediate friction level with small fluctuations over the whole test duration, indicating relatively stable tribological behavior. In contrast, Sample 2 (double-layer same-alloy overlay) shows a significant increase in friction in the mid-to-late stage, accompanied by large oscillations, suggesting unstable transitions in the sliding process. Worn surface observations confirm these tendencies: Sample 1 is characterized by continuous parallel grooves with limited adhesion and fine spallation, as shown in

Figure 12a,a1. Sample 2 shows pronounced lips at groove edges, smeared transfer layers, and localized delamination and fatigue cracks along the sliding direction, as shown in

Figure 12b,b1. Sample 3 exhibits a compact glaze-like layer composed of dense flaky/blocky oxide–transfer films, intersected by through-thickness cracks and local spalled regions, indicating brittle fracture and re-exposure after prolonged sliding, as shown in

Figure 12c,c1.

These features correlate well with the underlying microstructures. The near-surface region of the single-layer coating consists of a hierarchical “epitaxial columnar→cellular–dendritic→locally fine equiaxed” structure. Dispersed Fe3C/Fe2Nb particles in the Ni-Cr matrix and a relatively high fraction of high-angle grain boundaries (HAGBs ≈ 52%) enhance resistance to plowing and promote crack deflection. As a result, the friction coefficient remains moderate with limited fluctuation, and the dominant wear mechanisms are mild abrasive wear with local adhesive wear. In the double-layer coating, the upper layer contains long, strongly textured columnar grains. Although the interlayer remelted band refines the microstructure locally, the pronounced orientation anisotropy and interdendritic segregation (chain-like carbides along dendrite arms) in the top layer facilitate adhesion–fatigue coupling under tangential loading. The wear process evolves from initial abrasive grooves to rapid formation and periodic delamination of adhesive transfer layers, leading to an increased and highly fluctuating friction coefficient, as well as large-scale spalling and lip formation. This trend is consistent with the higher near-surface HAGB fractions and smaller SDAS measured in the interlayer-containing coating compared with the single- and double-layer overlays.

For Sample 3, the ERNiCrMo-3 interlayer redistributes the substrate-to-coating chemical gradient into a smooth Fe-decreasing/Ni,Cr-increasing profile with Mo enrichment in the interlayer. This reduces interfacial embrittlement and suppresses excessive columnar growth in the ERNiFeCr-1 top layer. The near-surface microstructure consists of cellular–dendritic grains superimposed with an interfacial refinement band. During sliding, Mo promotes the formation of a dense tribo-oxide/glaze layer containing Cr

2O

3/NiO and MoO

3. This layer exhibits low shear strength, which explains the low and stable friction coefficient in the early and intermediate stages. With increasing sliding time and cyclic thermo-mechanical loading, the glaze thickens, develops through-cracks, and undergoes brittle spallation (blocky delamination in

Figure 12(c1)), causing the abrupt rise and fluctuation of friction at later stages. Accordingly, the dominant wear mechanism for Sample 3 is oxidative/glazing wear in the early-to-middle stage, followed by adhesion-spallation triggered by glaze fracture. The total wear volume remains the lowest among the three coatings, though control of glaze stability is required.

The overall wear resistance ranking is: Sample 3 (interlayer + overlay) > Sample 1 (single-layer) > Sample 2 (double-layer same-alloy). The superior performance of Sample 3 over an extended sliding duration arises from three key factors: (i) the interlayer provides chemical and thermophysical decoupling, mitigating substrate interfacial embrittlement and excessive columnar growth in the overlay; (ii) Mo enrichment facilitates the formation of a stable, low-shear composite tribo-oxide glaze; and (iii) the interfacial remelting refinement band and enhanced HAGB network improve crack deflection and energy dissipation. The single-layer coating benefits from dispersed second phases and HAGBs against plowing, but lacks a Mo-driven self-lubricating oxide film. The double-layer same-alloy coating is penalized by coarse columnar grains and interdendritic segregation, which accelerate adhesion-fatigue-type failure.

These findings suggest the following process guidelines: (i) prioritize the ERNiCrMo-3 interlayer+ERNiFeCr-1 overlay configuration; (ii) carefully control heat input and interpass temperature for the top layer to form a distinct but not excessive remelted band, promoting near-surface cellular–dendritic refinement and a high HAGB fraction while suppressing high-aspect-ratio columnar grains; (iii) retain sufficient Mo in the interlayer (avoid over-dilution) to support the formation of a stable MoO3/spinel-based glaze; and (iv) employ a reasonably high overlap ratio and surface finishing to reduce initial groove defects and extend the stable-glaze regime. Following these principles enables low and stable friction while mitigating late-stage glaze instability and spallation, thereby achieving an improved balance between wear resistance and resistance to cracking in service.

During sliding, the ERNiCrMo-3 interlayer facilitated the formation of a dense Mo-enriched tribo-oxide layer (composed of MoO

3, Cr

2O

3, and NiO). Since direct characterization via XPS or Raman spectroscopy was not performed, the composition attribution is supported by relevant literature: Ni-Cr-Mo alloys typically form composite oxide films containing low-shear-strength MoO

3, wear-resistant Cr

2O

3, and dense NiO during dry sliding, which collectively reduce friction and improve wear resistance [

31]. Specifically, MoO

3 acts as a self-lubricating phase, while Cr

2O

3 and NiO enhance the film’s compactness and adhesion. This Mo-enriched tribo-oxide layer explains the low and stable friction coefficient in the early-to-middle stages of the interlayer-containing sample.